Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fire in The Hills - Iranian and Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982

Uploaded by

Josue AlvaradoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fire in The Hills - Iranian and Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982

Uploaded by

Josue AlvaradoCopyright:

Available Formats

http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_214.

shtml Go OCT JAN FEB

👤 ⍰❎

103 captures 11 f 🐦

29 Oct 2005 - 12 Nov 2020 2005 2006 2007 ▾ About this capture

*ACIG Home*ACIG Journal*ACIG Books*ACIG Forum *

Articles ARABIAN PENINSULA & PERSIAN GULF DATABASE Latest ARABIAN

ACIG Special Reports

PENINSULA &

PERSIAN GULF

ACIG Database Fire in the Hills: Iranian and Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982 Email this article DATABASE

By Tom Cooper & Farzad Bishop Printer friendly page

ACIG Books, Articles & Media Sep 9, 2003, 23:02 US-Related News from Iraq

Central and Latin America Database Future Development of GCC Air

Forces; Part 2

Europe & Cold War Database Future Development of GCC Air

Forces; Part 1

Former USSR-Russia Database Hard Target: Rolling-Back

Iranian Nuclear Programmes

Western & Northern Africa Database

Shahab 3: an Advanced IRBM

Central, Eastern, & Southern Africa 22 September 2004: Parade in

Database Tehran

Middle East Database Baghdad Impressions

With the 7th Field Hospital in

Arabian Peninsula & Persian Gulf Basrah, Part 2

Database With the 7th Field Hospital in

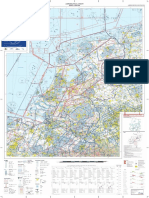

In the late summer and early autumn of 1982, in the Sumar hills on the border between Iraq and Iran, the two neighbours fought some of the fiercest battles of the whole First Persian Gulf War. The fighting in this Basrah, Part 1

Indian-Subcontinent Database area was not as massive as during many larger operations conducted before and afterwards. Yet, it included extensive use of air power by both sides, producing not only remarkable results, but also some of the most

controversial – and best known – claims of this war. Iraqi Super-Bases

Indochina Database Exhumating the Dead Iraqi Air

Force

Korean War Database

Second Death of IrAF

Far-East Database 22 September 2003: Iranian

Military Parade

LCIG & NCIG Section IRIAF Since 1988

ACIG Modeler's Corner US Air-to-Air Victories during

the Operation Desert Storm

Kuwaiti Air-to-Air Victories in

Search 1990

Go Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait; 1990

Persian 'Cats

All Categories

Advanced Search Iraqi Air-to-Air Victories since

1967

Iranian Air-to-Air Victories

Contributors Log-in since 1976

Tanker War, 1980-1988

Iraqi Air Force since 1948, Part

2

Iraqi Air Force Since 1948, Part

1

Fire in the Hills: Iranian and

Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982

Flying in a classic formation, resembling that seen so often when UH-1s of the US Army operated in South East Asia, a

section of IRIAA AB.205s is seen from another Iranian helicopter while transporting troops deep behind the Iraqi lines on I Persian Gulf War: Iraqi

the southern part of the Moharram TO, in autumn 1982. (Authors' Collection) Invasion of Iran, September

1980

I Persian Gulf War, 1980-1988

Kuwait Emergency, 1961

Oman (and Dhofar) 1952-

1979

The Iran-Iraq War started on 22 September 1980, when Iraqi air force fighter-bombers and bombers bombed almost every Iranian airfield in their range, while the Iraqi Army invaded Iran on several spots along the South Arabia and Yemen,

international border. This attack caused an all-out war, and a long, bitter struggle between the two countries began. 1945-1995

After 18 months of fighting, in 1982, the Iranian ground forces finally managed to organise themselves sufficiently to expel Iraqi forces from Iranian soil. In a series of offensives undertaken between March and June,

the Iranians out-manoeuvred and overwhelmed the main contingent of the Iraqi Army (IrA) inside the Iranian province of Khuzestan, which was completely liberated in the process.

During this fighting, the Iraqi military was truly battered: its strength fell from 210,000 to 150,000 troops; over 20,000 Iraqi soldiers were killed and almost 30,000 captured; two out of four active armoured divisions

and at least three mechanised divisions were decimated to less than a brigade strength, and the Iranians captured also over 450 tanks and armoured personnel carriers.

The Iraqi Air Force (IrAF) was left in no better shape, and after losing up to 55 aircraft since early December 1981, could count with barely 100 intact fighter-bombers and interceptors: a defector who flew his MiG-21

to Syria, in June 1982, revealed that the IrAF had only three squadrons of fighter-bombers left capable of mounting offensive operations into Iran at the time. The Iraqi Army Air Corps (IrAAC) was perhaps in a better

shape, and could still operate more than 70 helicopters.

The fighting in 1982 also took its tolls of the Iranian forces, but losses were not as heavy as those suffered by the Iraqis and – despite the hard-felt lack of heavy weapons and empty ammunition depots – spirits were

high. The Iranians felt they were fighting for a just cause – ending Iraqi occupation of the oil-rich Khuzestan. Having achieved this, they had to decide about their next step, so through the summer numerous meetings

were held between leading clerics, politicians and military officers. Theoretically, there was a potential to conclude the lengthy UN- and Algerian-mediated negotiations with several Arab states, accept the Saudi and

Kuwaiti offers to pay reparations for the damage caused by the Iraqi invasion of Iran, and end the war. But, this required negotiations with the regime in Baghdad and that was something the Iranian leadership would

not consider.

Bringing the War to Iraq

Instead, deluded by their own successes, leaders in Tehran decided to bring the war into Iraq, and topple the regime in Baghdad, particularly now that the position of the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein seemed much

weaker.

The Iranians just had to decide how to reach this objective. The professional military officers, who were against a longer war, suggested that it needed to be concluded swiftly, before military equipment shortages and

depreciations began to take their toll. As an alternative, some came forward with a plan for a bold and massive all-out thrust towards Baghdad, which was to be captured regardless of losses. Such ideas were dismissed,

however, seemingly because the Iranian political and clerical leaderships were not interested in a swift end to the war. Instead a decision was taken to crush the Iraqi war machine by capturing one area after the other,

in a hope that a series of massive blows delivered foremost by the Islamic Republic Revolutionary Guards Corps units (IRGC; better known as “Pasdaran”) would cause unrest or even uprisings from within the Iraqi

Shi’ite society. It was the first in a catalogue of huge mistakes, which was later not only to cost Iran a clear-cut victory in the war, but bring it to a verge of defeat.

The first strategic objective was the capture of the second-largest Iraqi city, Basrah. On 14 July 1982, after rejecting another UN call for a ceasefire, the IRGC started the Operation RAMADHAN. The military objectives,

however, were beyond the reach of the IRGC at the time. The Iranians supposed – wrongly – that they would hit one of the weak points in the enemy defences whilst Iraqi military was still in turmoil after recent

defeats, but they lacked proper intelligence. It was completely unknown to them, that the Iraqis had learned about the preparations for RAMADHAN, and had reinforced the defences of Basrah by additional units pulled

back from the central and northern front sectors. As a result, the poorly-trained Pasdaran and Basij forces attacked some of the heaviest fortified Iraqi positions in the Zeid (Fish Lake) and Shalamcheh areas, and after a

week of fighting were stopped in a hail of Iraqi defensive fire and flanking manoeuvres. Even the Iranian Chieftain main battle tanks (MBTs) and BMP-1 armoured personnel carriers (APCs) of the 16th and 92nd

Armoured Division could not change the outcome.

During this offensive, the IRGC for the first time deployed some of its armour – mainly T-55 MBTs and Type 63/531 APCs of the recently-established 30th Armoured Divsion IRGC, all of which had been captured

from the Iraqis during the previous engagements and for the first time were being grouped as independent units. Iranian armoured units were supported by the 21st and 77th Infantry Divisions, 58th Commando and

23rd Special Forces Brigades, 22nd and 33rd Artillery Groups, as well as the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th Infantry Divisions IRGC. The Islamic Republic of Iran Army Aviation (IRIAA) also deployed a sizeable helicopter

division, including 34 Bell AH-1J/T Cobras, and a number of Bell 204s, Bell 206s, Bell 214s, and Boeing CH-47 Chinooks in support role.

But the Iraqis – instructed also by a team of East German advisors – now started operating their Mil Mi-25 Hind and Aérospatiale SA.342L Gazelle attack helicopters in “hunter/killer” teams, which proved especially

effective. The tactics used by the IrAAC hunter/killer teams was simple but highly effective, as it put the best capabilities of both helicopter types to advantage: the Mi-25s would go in first and roll over the Iranian

positions firing 57mm unguided rockets, trying to suppress the anti-aircraft positions. The Gazelles would follow, using the confusion to fire their HOT anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs) against singled out Iranian

tanks.

Even if the IRIA and IRGC armoured units had put up a persistent fight, and continued to bulldoze their way towards Basrah into the month of August, in the end they suffered such heavy losses both in men and tanks

that a counterattack by the Iraqi armoured formations threatened to completely annihilate them. Only a final intervention by the IRIAA AH-1J Cobra gunships saved the remaining Iranian armoured formations from

certain destruction, and enabled them to pull back.

While the Iranians were making up their mind and organising their first series of offensives into Iraq, the Iraqis were working intensively to reorganize their damaged forces, and making preparations for the defence of

their country, while simultaneously purchasing new equipment from every possible source – and mainly with the help of Saudi and Kuwaiti loans. During 1982, they managed to re-establish contacts with Moscow,

convincing the Soviets to restart deliveries of aircraft and tanks ordered already in 1979, but stopped in September 1980. Additional deals with France were also concluded, including orders for more Mirage F.1EQ

fighters, SAMs, ammunitions and heavy weapons, including self-propelled artillery. Finally, huge numbers of tanks and F-7B fighters were ordered in China.

Expecting the Iranians would come back sooner or later, the Iraqis now initiated a series of air raids against the Iranian economy and civilian installations in the cities along the border, which were later to develop into

distinct and familiar patterns of this war – the so-called “War of the Cities” in which the IrAF played a dominant role. In addition, they started targeting Iranian and international shipping in the Persian Gulf along the

Iranian coast and the Khark Island, where most of the Iranian oil exports were loaded. This tactic later developed into the well-known “Tanker War”. In the event, the strategy initiated a war of attrition that lasted

right to the end of the First Persian Gulf War and resulted in heavy destruction on both sides, as the Iranians soon started to retaliate by targeting the Iraqi oil industry with precision air strikes.

During the fighting between Shalamcheh and Basrah, in the summer of 1982, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps

deployed its armour for the first time in the war. When this experienced problems with Iraqi defences, also Chieftain tanks

of the Iranian Army were sent to help. The Iraqis responded with vicious helicopter attacks, deploying "Hunter-Killer"

teams of their Mi-25 and Gazelle helicopters. The vehicles seen here were caught in the open and destroyed or disabled by

hits from HOT ATGMs. (Authors' Collection)

Eyewitness Account

It was the second morning of the Operation Ramadhan. The IRIAA firing teams, consisting of three AH-1 Cobras and one Bell 214 as SAR asset, continuously pounded Iraqi positions, to a degree that they persistently

asked over the radio for air cover.

During one such mission, of which 214 SAR crew were Maj. Jamshid Pour-Azad and Capt. Gheibi, three Iraqi MiGs suddenly appeared in the sky over the Iranian helicopters. The IRIAF FAC-officer responsible for the

area was swift to request air cover for the firing team, and soon two IRIAF F-4 Phantoms entered the fight and intercepted the Iraqis. In the meantime the helicopter team landed on a designated emergency range and

witnessed the close turning dogfight overhead. Pour-Azad could see air-to-air missiles being exchanged, before one of the Iraqi MiGs burst into flames and turned towards Iraq trailing smoke.

This moment of joy did not last long, because soon two IrAF Mirage F.1EQs joined the foray and quickly targeted one of the Iranian fighters with air-to-air missiles. The Phantom’s rear fuselage caught fire and dived

toward the ground. Both pilots ejected safely, but were seen landing on the direction of the Iraqi positions. This alarmed the SAR helicopter crew, who wasted no time in starting and taking off to the rescue of the

downed Phantom crew, despite Iraqi aircraft and helicopter gunships operating in the area. On the way towards the predicted landing zone, Iraqi anti-aircraft fire opened fire, and Iraqi snipers tried their best to hunt

down the downed pilots hanging under their parachutes.

As soon as the Phantom pilot touched the ground, the SAR chopper landed beside him and picked him up. Moments later, the navigator also made a hard landing and was quickly picked up too. However this was not

the end to the ordeal, as two huge Mi-25 Hinds decided to give a chase to the SAR team. The Iranians speeded away, trying to reach the positions of their ground forces, the suppressing fire from which forced the Iraqis

to change their minds and turn back. The team safely made it back to its base.

The Opponents

Following the costly failures at Shalamcheh and east of Basrah in July, during the rest of the hot summer, the Iranians changed the direction of their push - this time listening to the Joint Chiefs of the Islamic Republic

of Iran Armed Forces (IRIAS) and preparing operations directed towards Baghdad, initiated at a place from which the Iraqi capital was only 120km away. The first from a series of offensives was code-named MUSLIM-

IBN-AQIL.

This was an operation prepared by Iranian I Army Corps, commanded by Col. A. Rostami, including the 28th Mechanised Infantry Division (28th MID), and the 81st Armoured Division (81st AD), which were

reinforced by a large number of Pasdaran and Basij that had to suppress their petty rivalries and work together with the IRIAS against the Iraqi Army. The operation targeted liberation of some Iranian territory west of

the Sumar hills, still held by the Iraqis, and then capturing the Iraqi border city of Mandali, some 65nm (120km) northeast of Baghdad – the ultimate goal being Baghdad itself, if an appropriate crack in the Iraqi

defences could be caused.

The Iranian commanders always hopped that by making surprise attacks against Iraqi lines on the central or northern front there was a small possibility of catching the Iraqi Army off balance, or overstretched, and

breaking a whole part of the front. For this purpose, the Iranian troops were first to isolate the Iraqi pocket in Naft Shahr, and then reach the Mandali-Baqubah road at a point some 41nm (75km) from the Iraqi

capital, where the Iraqi Army held a large depot with huge vehicle parks and workshops.

The air support for the operation was to be given by a battalion of the IRIAA from the Kermanshah Army Aviation Group, including two dozen Bell AH-1J Cobras and Bell 214A Isfahans, and commanded by Capt. H.

Namazian. They were forward-based near Sumar and were to play a crucial role in supplying ammunitions to the advancing Iranian ground forces. In addition, the IRIAF prepared some 14 or 15 McDonnell Douglas

F-4E Phantom IIs from the 31st and 33rd Tactical Fighter Squadrons (TFS) at the TFB.3 near Hamedan, led by Capt. R. Salmaan and Capt. S. Khalili, respectively. Meanwhile, the 51st and 53rd TFS from the TFB.5 at

Omidiyeh, led by Maj. A. Sadeghi and Capt. R. Jamalan, respectively, prepared between seven and nine Northrop F-5E Tiger IIs.

Facing this limited Iranian task force was the whole Iraqi III Army Corps, consisting of the 3rd “Salaheddin” Armoured Division, newly rebuilt and equipped with T-72 tanks, the 5th and 6th Mechanised Divisions, and

the 11th Infantry Division, reinforced by at least one artillery, and one special forces brigade. At the time, most of these units were still not back to their full strength, but the Iraqi Army could count on increasingly

effective support from its IrAAC, even if it had no permanently stationed units in the area. Instead it had a series of main bases and forward airfields, all equipped with pre-positioned fuel and ammunitions, to which

reinforcements could be sent as needed.

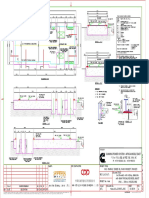

IRIAF F-4Es from TFB.3 armed with up to four Hunting BL.755 CBUs flew a number of interdiction- and close-air-support sorties during the Operations

Rhamadan, Muslim-Ibn-Aqil and Moharram, suffering only minimal losses in exchange for a considerable number of air-to-air kills as well. (Artwork by

Tom Cooper)

Iraqi Mi-25s

The IrAAC was established in late July and early August 1980, during preparations for invasion on Iran. It was based on the model of the French Army Aviation (ALAT). It operated all the helicopters used to support the

Army, and its flying crews and technicians were mainly trained in France, Soviet Union and the UK.

The IrAAC was not yet a fully developed – even if well-trained and competent – force, and its officers still had much to learn about heliborne operations. On many occasions it could do little more but to copy Iranian

tactics. This air arm participated in the war right since the start, flying hundreds of sorties every day: on 30 October 1980, for example, the IrAAC is known to have flown no less but 120 attack sorties. However, the

Iraqis lacked proper equipment – the heavily armed Mil Mi-8 was the workhorse of the IrAAC and while it was ideal for transporting troops and supplies, it was too large and inadequately-equipped for anti-tank

duties, and too vulnerable to Iranian interceptors. Equally, the Aérospatiale SA.342 Gazelle was too lightly armoured, and – until the arrival of the first larger shipments of HOT ATGMs from France – also inadequately

equipped for the anti-tank role. The other French-built helicopter in service was the Aérospatiale SA.316C Alouette III, procured in the early 1970s. Alouette IIIs were equipped with heavy machine-guns as well as

French-made AS.11 and AS.12 ATGMs. They were previously used in attacks on Kurdish insurgents, their missiles having devastating effects when used to target caves: the Kurds learned to fear the small French

helicopter more than anything else. Nevertheless, Alouettes were mostly used as liaison helicopters, and for artillery spotting, in northern Iraq.

Nevertheless, the Iraqis were willing to learn and stubborn: despite severe losses they had suffered in the two years of the war with Iran. The fact that their invasion ended with a failure which cost them dearly, forced

them to invest heavily in the increasing effectiveness of their arms – including their IrAAC. They were ready to invite foreign advisors and listen to any good ideas they had, especially in the connection with the Mi-25

Hinds.

By 1982, the IrAAC operated a total of eight squadrons, designations of which were in the range 60+ (probably 61 thru 68) and which boasted only some 70 operational helicopters in total, foremost Mi-8s, Mi-25s,

SA.342L Gazelles, and SA.316Cs (later on, the IrAAC was re-organized into two “Attack Transport Helicopter Wings”, the 1st and the 2nd). Each helicopter squadron was deployed in several detachments, distributed

along the front. For example, the No.64 Assault, Transport, Training, and Special Operations Squadron, the unit which operated all the Iraqi Mi-25s, had eight Mi-25s permanently based in pairs at Samarah, Baiji,

Mousel and Falujah, and equipped to drop bombs filled with chemical weapons – besides the usual SA.342Ls and Mi-25s.

Other Hind pairs were usually based at Basrah, near the Presidential Palace in Baghdad (where they acted as escorts for helicopters used by Saddam and his family), at Kut, Kirkuk, Nasseriyah, Jalibah, Routba, or Tallil.

Iraqi Mi-25s frequently operated from sites near several large early warning radar sites, which time and again became targets for notorious Iranian commando raids, most of which had been catastrophic for the Iraqis.

During the fighting in autumn 1982, Mi-25s of the No. 64 Assault, Transport, Training and Special Operations Squadron were deployed in two detachments and were based at Kut, Mousel, and Kirkuk, from where

they could also operate against the Kurds, which already then had to learn to evade heavily armed Iraqi helicopters and their devastating firepower, frequently put into use against villages and refugee convoys. Maj. K.

A’ti commanded the northern detachment, designated the 1st Special Operations Unit No.64 Squadron, while Maj. Badreldeen commanded the southern detachment, designated the 4th Special Operations Unit.

In 1982 the Mi-25 was still a relatively new asset in the Iraqi arsenal. Iraqis ordered their first 12 Mi-25s in 1977, as a part of a huge agreement which by 1979 saw total orders for no less than 250 other Soviet-built

aircraft and helicopters (most of them were delivered only after 1982, as in September 1980 the USSR stopped most of its arms deliveries to Iraq). The first four Mi-25Ds arrived in Iraq in April 1980, followed by four

more in June of the same year. By the time of Iraqi invasion of Iran, on 22 September, six remained operational with the 4th Squadron of the newly formed IrAAC, as one was under repair and another was shot down

by Iranian F-14As on 7 September, during some of the first serious skirmishes between Iraqi and Iranian forces. Three more Mi-25s were lost in combat against Iranians by the end of the same year, and after losing the

fifth example, in January 1981, the Iraqis ordered sixteen new Mi-25s (despite the fact that “officially” Moscow had declared an embargo on the export of weapons to Iraq after it invaded Iran). Finally, in May 1982

another order for 18 examples followed, and it seems that some examples from this batch started arriving in Iraq by October of the same year.

The Soviets were particularly slow to deliver Hinds at the time, as the demands of the war in Afghanistan were considered more urgent. By August of 1982, only some 20 Mi-25s were in service with the IrAAC. All

were flown by the pilots of the No.64 “Assault, Transport, Training, and Special Operations Squadron”, which consisted of the most capable and most loyal Iraqi helicopter pilots. The trust the Iraqi regime felt for this

unit was such that two Mi-25s were permanently based somewhere in or around Baghdad, where they could constantly cover any movement of the Iraqi top leaders.

Iraqi Mi-25 pilots liked the type, praising its good range, weapons load, speed, and versatility, however, they disliked the weaknesses of the weapons system – which lacked precision and reliability – as well as the size

of the helicopter and its lack of agility. Recalling the fact that especially the IRIAF F-5 pilots developed a predilection for hunting down Iraqi helicopters over the front, the former IrAAC Mi-25 pilot, Capt. Aduan

Hassan Yassin, concluded: “I always felt like flying the largest target around.” Indeed, the Iranians soon learned to fight the Mi-25 by all available means, and would frequently organise proper “hunts” for them.

As a result, by the summer of 1982, the IrAAC invited a team of East German advisors to help develop better tactical methods for the use of the Hind in combat – a fact still fiercely disputed by a number of high-

ranking Iraqi officers. One of the outcomes was the – as previously mentioned – introducing hunter/killer teams, in which Mi-25s were used to suppress Iranian air defences, in order to enable the more vulnerable

Gazelles to use the HOT ATGMs. Five such teams were organised, one of which was led by East German Capt. Ralf Geschke.

Interestingly, the Iraqis never considered their Mi-25s to be “anti-tank” helicopters, and preferred to describe them as “combat transport helicopters.” Therefore, the Iraqi Mi-25s were never equipped with AT-6s, nor

was this weapon – contrary to numerous reports in the Western and Russian press – ever delivered to Iraq during or after the First Persian Gulf war. They were not even deployed to Iraq for testing purposes, the Soviets

did all the combat testing for the AT-6 in Afghanistan.

Also, contrary to other reports, Iraqi helicopters were never armed with the AT-4 Fagot/9K11 ATGMs either. Although this weapon was delivered to the Iraqi Army even before the war, and despite their wish to do so,

the Iraqis could not mount it on their Mi-8 or Mi-25 helicopters for two reasons: because neither type had a stabilised sighting system for the gunner, and because of the fierce back blast (of between three and five

metres) the motor of this missile develops on launch. The lack of the stabilised gun system prompted the Soviets to choose the AT-2/Scorpion missile as the main armament for the Mi-25 first of all. On the other side,

the large back blast was the reason why the idea of mounting the AT-4 so it could be fired out of the side doors of the helicopters, was also dropped. Therefore, for the entire war, the only ATGM used by the IrAAC

Hinds remained the slow and weak AT-2B/C, 1.000 of which were delivered together with the first two batches of Hinds to Iraq. But, in fact, as Col. Sergey Bezlyudnyy and Maj. Dark Gurov - two former Soviet

advisers who spent no less than six years in Iraq during the war with Iran (1980-1983, and 1986-1989) – remarked, Iraqi Mi-25s flew combat missions very seldom equipped even with these weapons.

A well-known photograph of an IrAAC Mi-25 thundering low over an Iraqi mechanised formation on the flat plain of Shalamcheh. (US DoD via

Authors)

Mi-25s of the No.64 Squadron IrAAC, as used during the fighting in autumn 1982. In an attempt to help improve the identification process, the IrAAC

started to paint large national flags on several sections of its helicopters (including the bottom). (Artwork by Tom Cooper)

IrAF in Autumn 1982

Finally, the IrAF could at the time deploy a few depleted squadrons of MiG-23MS’ (the No.39), MiG-21MFs, and a single unit of Mirage F.1EQs (No.79 Squadron), plus an equivalent of two squadrons of Su-20/-22s

deployed with five units, and two MiG-23BN units to five different bases east of Baghdad and three along the Iranian border (the last three being Subakhu, Baqubah, and Sheikh Jassem).

At the time, the Mirage F.1EQs only seldom operated over the front and were rather kept back for the defence of strategically important installations inside Iraq. Similar was the situation with the No.96 Squadron IrAF,

which was already operational with MiG-25PDs deployed in two or three flights (one of which was entirely manned by Soviet and other East European pilots) in northern, southern and western Iraq. Iraqi MiG-25PDs

were sometimes sent to intercept aircraft – often civilian - inside Iran. In contrast, the No.84 Squadron – with MiG-25RBs – was foremost occupied with operations against Khark Island, and was not especially useful

for fighting over the front.

A MiG-23MS in the colours of the No.39 Sqn Iraqi Air Force, as seen at al-Taqaddum, in the early 1980s. (Artwork by Tom Cooper)

Weapons of Trade

The rough terrain along the central part of the Iraqi-Iranian border forced both sides to make extensive use of their airpower. Such terrain could offer more protection to fliers of both sides, and was therefore

preferred when compared with the completely flat terrain on which most of the fighting on the southern sectors took place. By 1982, namely, both the Iraqis and the Iranians realised that this war would be won by the

side that managed to conserve its forces and resources the longest.

While both sides came to this conclusion, the results were very different for the Iraqis compared to those of the Iranians. For the Iraqi regime, which could replace the losses in aircraft and helicopters more easily than

the Iranians, the use of airpower had its merits even if it was never considered decisive. The IrAF and the IrAAC were constantly suffering considerable losses, and by the summer of 1982 were hardly in operational

condition, but the loss of a single pilot – or a flying crew – had less impact on the morale and the total combat capability of the Iraqi military than a loss of a whole regiment or brigade of ground troops.

For the Iranians, the situation was completely the opposite: their ground forces were numerically superior, but they lacked heavy equipment, and their flying services had to carefully husband equipment and qualified

crews. Therefore, they had to make a very careful use of airpower, and to deploy it only when ultimately necessary. Yet, the regular Iranian Army, organised and equipped according to the US Army experiences from

the Vietnam War, depended heavily on helicopters, especially when fighting on such rough terrain on which the operations in late summer and early autumn 1982 were to be undertaken. In areas where there were no

good roads, fast moving battles heavily depended on supplies flown in by Bell 214s and CH-47Cs, and on the fire-support from Cobras. Even the Pasdaran and Basij learned to appreciate the appearance of the IRIAA

helicopters overhead, and a sight of only one or two Cobras usually helped considerably bolster the morale of the troops. The Iranians knew how good their pilots were, and the regime in Tehran was glad to use the

popularity of IRIAF and IRIAA aces – completely neglecting the fact that almost all of them had actually been trained by the “Great Satan” – for its purposes.

In 1982, the Islamic Republic of Iran Army Aviation (IRIAA) was a battle proven force, highly experienced in operational use of helicopters. During the 1970s, it purchased a huge number of attack and transport

helicopters, including 202 AH-1J Cobras, 287 Bell 214As, and 214 AB.206 JetRangers. Approximately 20 additional AB.205s were used for SAR and CASEVAC tasks, while the large fleet of 118 CH-47C Chinooks (64

from the US and 55 from Italian Elicopteri Meridionali) were used for all possible tasks, including normal troop-transport duties, CASEVAC etc.

By 1982 quite a few Bell 214As and some Cobras had already been lost during the fighting in Oman, in the 1970s, and then against the Kurdish uprisings in the Iranian Kurdistan, in 1979 and 1980, as well as the

subsequent repulsing of the Iraqi invasion. But, the IRIAA’s fleet remained a force to reckon with, with the fourth largest helicopter fleet in the world, and could still boast over 620 helicopters. These were organised

into three so-called Direct Support Combat Groups, each operating an attack helicopter division (equipped with AH-1Js, Bell 214s/AB.205s and AB.206s), and a “General Support Group” of medium and heavy

transport helicopters, equipped with Bell 214As, and CH-47Cs.

The IRIAA found it difficult to concentrate a large number of helicopters at a particular section of the front, mainly because the front was so long. It also still lacked enough crews to man all the available helicopters, let

alone to train new ones. Contrary to the usually accepted “version,” however, maintenance problems were minimal, foremost because in the 1970s a large helicopter repair facility; the Iran Helicopter Support and

Renewal Company (IHSRC), was established by Bell Textron/Bell Corporation at the eastern part of the Mehrabad airport, and it was becoming increasingly competent and independent from any foreign help. This

facility was now capable of refurbishing and completely rebuilding all helicopter types in Iranian arsenal. Also, the maintenance capabilities of the field units were constantly increasing, and even if there was a steady

shortage of trained personnel, the flying crews were meanwhile battle-hardened and experienced. Only the poor strategy of the Iranian political leadership precluded the IRIAA to be – together with the IRIAF – of

decisive importance for the outcome of the war. In the autumn of 1980 these two services had stopped the initial Iraqi drive into Khuzestan almost alone and at a time when Iranian ground forces were largely in chaos.

This confirms their capability at the time.

An AH-1J Cobra ("International") as seen in the livery of the "Islamic Republic of Iran Army

Aviation" (IRIAA) during a forward deployment near frontlines. Note the tents in the camp for

crews in the rear. (Authors' Collection)

Approaches to Baghdad

The MUSLIM-IBN-AQIL offensive was launched on the evening of 1 October 1982, with small IRGC units in high spirits attacking Iraqi positions high on the hills, followed by mechanised Army units in the morning.

Shortly after the dawn, the F-5Es from Omidiyeh TFB.5 and F-4Es from Hamedan/Nojeh TFB.3 flew their first strikes, hitting the nearby Iraqi logistical centres. On the ground, there was a lack of co-ordination between

the IRIAS and the IRGC units and so the battle soon developed into a bloody struggle for every hill. The Iranian advance was very slow, and by 4 October they still had not reached Mandali. On the contrary, the Iraqis

counterattacked towards Sumar, supported by artillery and helicopter gunships. That was the start of a massive air-land battle.

According to the original plan for MUSLIM-IBN-AQIL, the 31st and 33rd TFS’s were to support the operation by flying nine to 12 strike sorties per day, with the 51st and 53rd TFS’s following with a similar number of

close air support sorties. This was clearly not enough, so the IRIAA Cobras did their best by flying numerous daily combat missions per airframe and the crew.

The IrAF responded by sending more and more fighter-bombers as it deployed additional units at airfields near the front. But, the IRIAF then deployed one MIM-23 HAWK SAM site to cover the battlefield near Mandali,

which became operational on the morning of 5 October, downing one MiG-23BN. In the middle of persistent quarrels between the IRIA and the IRGC, on the evening of the same day the Iranians started the next phase

of their operation, this time better combining their infantry and armour. In the event, they were stopped on the hill overlooking Mandali, some two or three kilometres outside the city. Some outskirts of Mandali were

held only very briefly, as in the morning the Basij unit was hit by Army artillery’s friendly fire after it started an attack almost two hours too early.

The Iraqis deployed their special forces brigade of the Republican Guards, trained for combat in urban areas and heavily supported by Mi-25 and SA.342 “hunter/killer” teams. By 7 October, the Iranians had lost their

positions overlooking Mandali; but, they held off the other Iraqi counterattacks and also claimed seven Iraqi fighter-bombers as shot down, in addition liberating 150km2 of their own soil. Subsequently, the IRIAF

resorted to counter attacks against the local Iraqi airfields at Subakhu, Baqubah, and Sheikh Jassem, forcing the IrAF to temporarily disperse its fighters concentrated there. Iran also lost a Cobra, piloted by the senior

IRIAA regional commander and tactician; Capt. Yahya Shemshadian, on that day. In turn, on 10 October, while covering a Boeing 707 tanker which was supporting one of these attacks, Maj. Jalal Zandi shot down two

Iraqi MiG-23s while flying an F-14A – a claim again fiercely denied by Iraqis.

The IRIAF was generally more successful in air combats at the time, mainly owing to the superior training of its pilots, but also equipment and firepower of its fighters. Besides the two MiG-23s downed by Maj. Zandi,

by the end of the month, also one Su-20 (by F-4s), two MiG-21s (by a combination of F-4s and MIM-23 Hawk SAMs), one SA.342 (by an F-5F), and two Mi-8s (both by F-5Es) were confirmed shot down over the

MUSLIM-IBN-AQIL territory of operations (TO). In response, the Iraqis claimed to have shot down no less than three Tomcats, eight Phantoms, five Tigers and at least 20 IRIAA helicopters. In fact, Iranian actual losses

were one F-4E, shot down by AAA over the Al-Rashid AB, near Baghdad, one F-5E (by SA-3 or SA-6) near another Iraqi air base, and one AH-1J, intercepted and shot down by IrAF Capt. Ahmad Salem, who almost

crashed his MiG-21 while trying to turn into his slow target at low speed and altitude.

The Iranian fleet of F-14A Tomcats remained fully operational and were used to excellent effect during the war. The F-14A 3-6079, shown here, was the last

example delivered to Iran and one of the most distinguished during the whole war. At least a dozen Iraqi aircraft were shot down by different pilots flying

this Tomcat. Note that this F-14 is shown here as it appeared early during the war: without the fin flash, and still wearing the title "IIAF" (instead of "IRIAF")

under the cockpit. Exact reasons for this remain unknown, but it is possible that this Tomcat was put into deep storage upon delivery, and returned to service

in a rush. (Authors' Collection)

Mi-25 vs. F-4

Iraq’s overlaims for the numbers of Iranian aircraft shot down in air combats and by air defences was characteristic for this war; many Iranian reports were not much better. But, the most controversial of all the Iraqi

claims ever was published on 27 October by the Iraqi magazine “Baghdad Observer,” a publication controlled by the Iraqi regime and targeting Western reporters. In the report with the title “The Day of the Helicopter

Gunship” an air battle was briefly described that supposedly developed several days earlier, and in which one Mi-24 Hind attack helicopter had shot down an Iranian F-4 Phantom. According to the “Baghdad

Observer,” the engagement happened “north of the Eyn-e Khosh area” and the Phantom was destroyed by a “next generation, long-range, AT-6 Sprial ATGM,” fired by a Mi-24 helicopter specially prepared and

brought to Iraq by the Soviets in order to test the AT-6 missile in the air-to-air mode.

Ever since, this claim has been making rounds in various Western, Ukrainian, and Russian publications. In general, this claim has widely been accepted as “authentic,” and was considered as “confirmed” even by

observers with considerable knowledge about helicopters and anti-armour warfare, or former dignitaries of the Soviet Air Force and airspace industry. Most Russian and Ukrainian observers use it to “confirm” the

capabilities and firepower of the Mi-24 attack helicopter and the AT-6 missile, even if very few people know anything about the background of the claim, or its initial source, while others are obviously ignoring these,

while maintaining that the claim was confirmed by “US intelligence.”

Significantly, even Western armoured warfare experts who are usually sceptical to accept any kind of “Arab” claims – especially for destroying such an advanced product of Western technology like an F-4 Phantom II

fighter-bomber – have shown more than ready to accept that this incident really happened. Considering the number of sources and their authoritativeness, it seems therefore not easy to dispute anything in this context.

Under closer scrutiny, the reality turned out to be completely different and this case illustrates once more how poorly the air war between Iraq and Iran has been researched so far.

The more one looks into this case, the more evidence there appears to be that there was no engagement between Iraqi Mi-25s and Iranian Phantoms – at least with the claimed result – in the time and place stated. On

the contrary – it appears that the actual source for all the publications which so far mentioned this claim – regardless of being Western or East European sources – is the same: the report of the Washington based

“Foreign Broadcast Information Service” (FBIS), which repeated the claim of the Baghdad Observer on the page E 2 of its Communiqué No. 885, FBIS-MEA-82-209, from 28 October 1982.

Even if originally established by the CIA, FBIS is no “US intelligence,” but rather a service compiling reports from all possible foreign media sources and broadcasts, and reporting these to different US services,

government agencies, and branches of military. FBIS neither confirms nor denies reports it is forwarding: it simply reports what was reported by somebody else. This is frequently ignored, especially by an increasing

number of research works published in recent years, many of which meanwhile explain that this air battle actually happened on 27 October 1982 - that means, on the same date which the claim had actually been

published for the first time in Baghdad Observer, which in turn obviously described that the engagement had happened several days earlier!

Actually, ever since that report was published for the first time in the Baghdad Observer, no new details about this engagement appeared: no gun-camera footage (all Iraqi Mi-25s, and all Soviet Mi-24s were equipped

with gun-cameras), no narratives by the (unknown) pilots who supposedly managed that feat (especially surprising, given the fact that the crew of the scoring Mi-24 should have been Russian), not even a closer

description of how this engagement developed; nothing, except some rumours from Russia, that this battle “must have happened,” if for no other reason, then because the Soviets and Iraqis had supposedly organised a

party to celebrate this success several days before the report in Baghdad Observer was published.

Research about theoretical possibility that the Soviets might have deployed some AT-6-equipped Mi-25s to Iraq brought no positive results whatsoever. As revealed earlier, the Iraqis never got any AT-6s. Furthermore,

while both the Iranians, and later the US forces during the Second Persian Gulf War, in 1991, have captured hundreds of Iraqi ATGMs, including such Western products as Milan, HOT, AS.11, and AS.12, or Soviet-

produced AT-2s, AT-3s, and AT-4s – no AT-6s, nor any traces of them in the Iraqi military, were ever captured or found. In addition, during the early 1980s, the Soviet Air Force was so short of Mi-24s due to the war

in Afghanistan, and under such pressure to field as many Mi-24s as possible with units facing the NATO, that deliveries of Mi-25s to Iraq slipped badly behind the schedule. At one point the Soviets were forced to even

take several East German Mi-24s, which were in the USSR for refurbishment, and press them to service in Afghanistan! When these helicopters were returned to their owners, a number of them had been found having

patched-up bullet holes in the fuselage.

It should be remembered that in 1982 relations between Moscow and Baghdad were not close enough for the Soviets to consider sending one of their most important weapons to Iraq. Particualarly as they were already

working on using the R-60 (ASCC-Code: AA-8 Aphid) short-range air-to-air missile as the main air-to-air weapon for the Mi-24, because they were well aware that the AT-6 could not be used in that role: the version

available at the time – the 9M114 (AT-6A) – was so poorly manufactured that it constantly failed even when tested under ideal conditions.

This fact was confirmed by a series of tests conducted by the US Army on the Aberdeen Proving Grounds during the 1980s and 1990s under the code-name Passive Nova 1, 2, and 3, respectively, and using a total of

120 AT-6s clandestinely purchased from different East European sources. Conducted by top US Army personnel, expertly trained in the use of Soviet-produced weapons systems, these tests showed that only four out of

100 AT-6s fired against targets moving at speeds of up to 15km/h would score a hit and destroy the target. The testing against stationary targets ended with only slightly better results, as only eleven out of 100 AT-6s

would hit and destroy the target – and that while being fired from a fixed tower, not from a helicopter diving at high speed and flown by a crew under stress and in hurry! US Army personnel concluded from the tests

that the most reliable part of the AT-6 was the warhead (despite its small diameter) and that the weapon was highly efficient – if it managed to score a hit, which, however, would did not happen very often. In short,

not only that these facts completely contradict Russian sources which claim a hit probability of 70-80% for the AT-6, but - statistically - there is also no possibility that the AT-6A could hit a target moving at 350-500

knots while fired from a helicopter which is also moving. As a matter of fact, the claimed hit probability of 70-80% for the AT-6 is probably valid only for the AT-6B and AT-6C versions, and only for rounds fired

during the trials in the later 1990s. In 1994, the Russians have completely rebuilt and upgraded their whole remaining stock of AT-6-missiles. Obviously, they have had good reasons to do so!

Some East European sources seem to have known this, and therefore they claimed that the Mi-24 scored this kill using unguided rockets and machine-guns, instead of AT-6s. Albeit, the same sources stated that this

happened on 27 October 1982, which is actually the date on which the initial claim was published by the Baghdad Observer. Therefore, and as the same sources have not offered any additional details about this

engagement, but have also added quite a few other mistakes, there is a credible doubt about the quality of research these sources have completed about the air war between Iraq and Iran at all. In another case, there is a

claim that the kill was actually scored by the AT-4 “Fagot” ATGM, a weapon indeed delivered to the Iraqi Army by the Soviets. The fact is, however, that the IrAAC had given up all efforts to mount the AT-4 on its Mi-8

or Mi-24 helicopters, for reasons mentioned above.

An AT-2/Scorpion missile as seen on an IrAAC Mi-25 that was captured by US Army, in 1991. The AT-2 remained the sole ATGM used by Iraqi

Hinds during the whole war: no AT-6s were ever delivered to Iraq, and the Soviets never sent any of their AT-6-equipped Mi-24s to that country.

Consequently are all claims for an Iraqi Mi-24 to have shot down an Iranian F-4 Phantom using AT-6 missiles false. (US DoD via Authors)

On the contrary, a very intensive research with the help of several former Iraqi and Iranian pilots brought no confirmation that an engagement of this kind happened in the given area at the given time – and especially

not with the result as claimed by Baghdad Observer. Two former Iraqi helicopter pilots who flew with the 4th Squadron IrAAC in 1982, and three other former officers of the Iraqi military remember being told about

how Iraqi helicopters had shot down Iranian helicopters time and again during the war. They remember also that pictures of the wreckage of Iranian helicopters were shown to them, and they also remember many of

their comrades being killed when Iraqi helicopters were shot down by Iranian helicopters and fast jets. But, they never heard about any claim that any of their Mi-25s had shot down an Iranian F-4, nor about the

Soviets ever deploying any Mi-24s and AT-6 missiles to Iraq and achieving anything similar. The closest any IrAAC Mi-25 ever came to doing something of this kind was in January 1981, during the Battle of Susangerd,

when a Mi-25 armed with four Scorpion missiles and four UV-32-57 pods by accident confronted an Iranian F-4 Phantom that was attacking Iraqi ground forces. The gunner in the front cockpit of the Iraiq helicopter

took notice of the approaching F-4, sighting the smoke from its engines, and notified the pilot: he then unleashed all of 132 rockets calibre 57mm towards the Iranian fighter that flew at low level, and perpendicular to

his flight pt. The Iraqi pilot never claimed he had shot the Iranian fighter, nor had any other Iraqi sources claimed anything similar – until the report in Baghdad Observer, over a year later.

All of Iraqis interviewed by the authors consider such claim to either have been a propaganda plot by the Iraqi government – which, after severe setbacks from the previous fighting during 1982, was in a dire need of

some good news at the time this claim was published. Or, so they say, there must have been a smart Iraqi journalist who tried to rewrite the same incident in another way.

Both of former IrAAC pilots confirmed – just like US documents released to the authors under several FOIA inquiries – that the AT-6 was never accepted to Iraqi Army service, especially not by IrAAC Mi-25s, and that

the Soviets also never tested that weapon in Iraq. To the best knowledge of the authors, the IRIAF wartime records, as well as other official documents mention no losses of any F-4s or F-5s over the front near Eyn-e

Khosh in October 1982, and no losses of any Iranian fighters to Iraqi fighters ever. Finally, none of several dozens of other former Iraqi and Iranian pilots and officers interviewed can remember about hearing any

similar claim either: several of them actually ridiculed the idea. As a result, we can only conclude that a Mi-24 never did shoot down an F-4 Phantom in the Eyn-e Khosh area during October 1982.

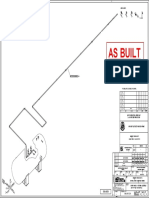

Phantom REALY meets Mi-25: as an IRIAF RF-4E thundered low over the Iraqi forward airfield near

Suleimaniyah, in autumn 1982, it took this photograph which shows two parked Iraqi Mi-25s. (Authors'

Collection)

Operation “MOHARRAM”

Just few days after the Operation MUSLIM-IBN-AQIL was initiated, the Iranians already started preparing their next offensive, code-named MOHARRAM. For this operation, the IRIA concentrated three divisions of the

III Corps, reinforced by five brigades of Pasdaran, and supported by 16 to 18 AH-1J Cobras organised in two regiments of the 1st Attack Helicopter Group, commanded by Maj. A. Bassiri and Capt. K Oweysee,

respectively, and deployed from Esfahan to TFB.4. Eight of the deployed Cobras were TOW-capable, and with them also 300 TOWs were forward-deployed. Among the crews who were to participate in this operation

were Capt. Ali “Gravedigger” Shafi, and his gunner, Warrant Officer Amir Ala’i – one of the best Cobra crews the IRIAA ever had, with quite a long list of successes to their credit. In addition to the helicopters, the

Iranian Gendarmerie and IRIAA were also to use a small number of Cessna O-2A Bird-Dogs as forward air controllers, foremost for coordination of their air, helicopter, and artillery attacks. (By 1982, these O-2s were

also used by the Gendarmerie for anti-drug smuggling operations).

The IRIAF was also better prepared for this offensive than it had been for MUSLIM-IBN-AQIL. At TFB.4 near Dezful, the 41st and 43rd TFS’s prepared a dozen or so F-5Es and F-5Fs, and they were reinforced by the

32nd and 34th TFSs, commanded by Maj. Shahram Rostami and Col. A. Fatahe, respectively, which flew in some 12 F-4Es. In addition, the 81st TFS from Esfahan was to fly constant Tomcat CAPs over the front, foremost

in order to escort at least one Boeing 707-3J9C-tanker (also equipped with “Roving Eye” US-supplied ELINT-equipment) which was to support the Phantoms participating in the operation. In this way, the Phantoms

and Tigers were to operate more freely over the front, where they could better concentrate on supporting ground troops and worry less about Iraqi interceptors and helicopters.

Although the Iranians had amassed sizeable forces for MOHARRAM, which could have posed a threat if they had breached Iraqi lines and neared the approaches to Baghdad, the actual objective of the operation was

limited, to say the least. First, the deployed forces were to secure several hills still inside Iran, and then take the large Bayat oilfield. In the last phase, the industrial towns of Tib, Zobeidat, and Abu-Qarrab and

associated oilfields were to be taken, and eventually the Sharahani-Zobeidat road, which could be used for an advance towards Ammarah, was to be cut off.

As it transpired, the bold drive deep into Iraq, eventually led by Iranian mechanised forces, was stopped at its first phase by Iraqi minefields and defensive fire – in addition to heavy rain. The initial attack by Basij,

started on the night of 1 November 1982, run directly into an extensive minefield causing many casualties. Meanwhile, the Iranians were more successful on the Bayat oilfield, making some gains and capturing 50 oil

wells, before the Iraqis moved in two brigades from the north, and stopped the advance.

By the dawn of 2 November, the IrAF, the IrAAC, the IRIAF and the IRIAA had thrown everything they had into the battle, with the Iraqis trying to block a further Iranian advance towards the west, and the Iranians

trying to suppress Iraqi armour, which was constantly inflicting losses on their infantry. The IRIAF Tomcats intercepted numerous Iraqi formations, claiming seven MiGs, Sukhois, and helicopters as shot down. The

Iraqis had fiercely denied suffering such losses, but in event the IRIAF established local air superiority, enabling TFB.3 Phantoms to bomb Iraqis with BL.755 CBUs, destroying scores of tanks and other vehicles. (Until

today, most of Iraqi sources deny the Hunting BL.755 cluster-bomb units were as effective as most Iranian sources claim; the Iraqis stress that up to 80% of the bomblets dropped from BL.755 failed to detonate). Then

the IRIAA Cobras and the Gendarmerie O-2As appeared over the battlefield and started rolling the Iraqi tanks back.

By constantly holding three to four AH-1Js over the front, but moving them up and down between the hills under coordination from O-2As, the IRIAA fliers created the feeling of dozens of them attacking almost

simultaneously, and several captured Iraqi officers even asked if the IRIAA had more Cobras delivered from the USA. In fact, the Iranian Cobra pilots used the “classic” tactics of US Army Aviators, called “Dead

Ground,” in which they would repeatedly approach the same area from several different directions, all the time flying behind the cover (low hills, earthen depressions, rock outcroppings) at high speed, then enter a

hover, do a short “pop up” manoeuvre to acquire the targets and fire, and then move back behind the cover. When using 20mm guns or unguided rockets, they would usually disappear before the Iraqis could detect

their presence. The situation was barely different when TOWs were used, as once the missile would be fired, Iranian pilots would bring their helicopters back behind the nearest cover, only keeping their nose over the

obstacle (so to be able to guide their weapons), and thus exposing only the part of the rotor and a very small part of the fuselage to the enemy. Using this tactic, on 2 November and during the following days, the IRIAA

Cobras destroyed at least 106 Iraqi MBTs and 70 APCs. Capt. Shafi and WO Ala’i were reportedly alone responsible for the destruction of 26 Iraqi tanks and other vehicles using TOWs and unguided rockets, as well as

two Gazelle and one SA.316C Alouette (used as forward artillery observer) with 20mm cannon fire. The IRIAA also suffered some losses during early November 1982 in the MOHARRAM TO, including one AH-1J to

Iraqi anti-aircraft guns, and one O-2A, probably shot down by SAMs.

Due to this success, by the time the third phase of the Operation MOHARRAM was initiated, on 6 November, the Iranian forces had reached the strategic Sharahani-Zobeidat road, cutting the most important Iraqi

logistical route in the area. Using helicopters to rapidly resupply and reinforce their forward units, they immediately started the assault on Zobeidat. The town was captured, but held only very briefly, as the Iraqis were

swift to react with a major counteroffensive of their elite Republican Guards units, which deployed their brand-new T-72 tanks, recently delivered from the USSR, driving them directly from Baghdad. Initially, the

Iranians had no effective weapons against the T-72, except TOW-armed Cobras and motorcycle-riding RPG-7 teams. Both were apparently ineffective against the front armour of the T-72s, so they had to search

positions which would enable them to engage from the flank. This considerably complicated the matters for Iranian fliers and fighters, and another IRIAA AH-1J was shot down by Iraqi ZSU-23-4s indeed while

operating against Iraqi T-72s. The losses of Iranian anti-tank teams of course, were appropriately higher.

By the 7 November, both sides suffered extensive losses, and were very tired of constant battles, so they settled to stabilise their new positions, or to improve them through local counterattacks. This led to continuous

activities in the air for the rest of the month, hampered only by the bad weather. After the initial shock due to the heavy losses on 2 November, the IrAF returned over the battlefield, but at high altitude, which proved to

be a wrong tactic, as Iranian F-14s were still patrolling the area. The first IrAF formation which reached the front on the morning of 7 November lost one of its Su-22s, flown by Capt. Raje’ Suleiman, who was

captured, before hastily being taken away. Several other fighter-bomber formations were subsequently forced to abort their missions after Iranian Tomcats were detected in front of them, and at one moment the

circumstances appeared to the Iraqis so desperate that they started preparing some of the No.64 Squadron’s Mi-25s for attacks with chemical weapons: only the high winds and rain stopped them from mounting such

mission.

The weather worsened in the following days, and by mid-November, the fighting on the ground bogged down in the mud. Nevertheless, the IRIAF managed to deploy one of its HAWK SAM sites near the front, which

went into action on the morning of 16 November, instantly shooting down one of four MiG-21s that attempted to bomb and strafe Iranian positions near the Bayat oilfield. Another MiG-21 was claimed shot down

shortly after by a Sidewinder fired from an F-4E. It is possible, however, that these two claims are for the same aircraft, then Iraqi sources deny the units that flew this type to have either suffered such losses, or flown

air-to-ground sorties at the time.

For the next four days, aerial operations were hampered by more bad weather, but on 20 November, both the IrAF and the IRIAF were flying again, and additional air battles developed as the fighters and helicopters

from both sides frequently run into each other while on air-to-ground missions. Thanks to the much better equipment of the Iranian aircraft, which helped their more experienced and superior trained pilots keep a

good situational awareness in airspace simultaneously used by larger numbers of enemy fighters, the IRIAF remained highly successful: an F-4E shot down an Iraqi MiG-23BN using Sidewinders, while F-5Es had a

particularly successful day, downing one Mi-8 with guns and one MiG-21 by AIM-9s.

On the morning of 7 November 1982, IRIAF F-14As shot down an Su-22 belonging to a formation

which was about to attack Iranian positions in the Moharram TO. IrAF Capt. Mohammad Raje'

Soleiman ejected safely and was captured by the Pasdarans shortly later. (Authors' Collection)

Iraqi Generals Meet Iranian Tomcats

During the war with Iran, for Iraqi generals the life depended on two factors, both of which had to do with their superiors: a) not taking too much action and make themselves too dangerous for the dictator in Baghdad

as to become his target, and b) not taking too little action as to appear incompetent as a military leader – and become a target for that reason too. In general, Iraqi high-ranking officers would seldom appear very close

near the front: instead they preferred to control the battle from the safety of “field headquarters,” rarely less than 30 or more kilometres in the rear. Sometimes, however, tours on the front had to be done, or the

“situation b” could develop: this was especially important because several cases were known in which Iraqi field commander deliberately distorted intelligence information to their superiors, and they had to visit the

front every time they wanted to see what was happening on the ground.

Exactly one such case provided the source of the next well known – at least in Iran and Iraq, but also within specific circles of the US military – and highly contentious claim from this period of the war: the one about

IRIAF interceptors downing five or six Iraqi fighters during a 17-minute engagement, followed by two IRIAA Cobras downing a helicopter carrying an Iraqi general, and the escorting MiG. This story is still being

perpetuated on the internet even now.

Over time the actual story has been altered, corrupted and misused so many times by both sides, that even the memories of former Iranian and Iraqi fliers can not be wholly relied upon. The following account has been

compiled during a series of interviews with several participants, as well as by using reports from both sides, and could therefore be considered as the most complete and accurate version published so far.

By 20 November 1982, the Iraqi troops in the MOHARRAM TO, on the front between Eyn-e Khosh and Musiyan, were in a critical condition. The Iranians had managed to capture several important oilfields, and cut

the main communication lines into the area; the IrAF was prevented from intervening by the IRIAF interceptors and SAMs; and the intervention efforts of the IrAAC ended with its helicopters either being shot down by

Iranian fighters and Cobras, or being hampered in their operations by strong winds and bad weather. Also, the Iraqi Army suffered heavy casualties, including 3,500 soldiers killed, and the whole sector of the front was

in danger of collapsing. Iraqi generals could already hear the first allegations from the dictator in Baghdad. Fearing that losses might be approaching those suffered during the spring Iranian offensives of 1982, Maj.

Gen. Maher Abdul Rashid of the Iraqi Army General Staff and commander of the III Army Corps, and Lt. Gen. Abdul Jabbar Mohsen, deputy commander of the IV Corps and Army spokesman, decided to tour the front

and meet with their local field commanders.

On the morning of 21 November, both generals boarded an armed Mi-8 helicopter, piloted by Capt. S. Mousa, which was escorted by two other Mi-8s and one Mi-25 acting as a pathfinder. Overhead, flights of four

MiG-21s and four MiG-23s were providing top cover, and these were continuously relieved by other flights as they ran out of fuel during the formation’s slow progress towards Mandali.

An IrAAC Mi-8 seen wearing the standard camouflage applied to this type in Iraqi service. Note large Iraqi national flags, used for easier

identification after several "blue-on-blue" incidents. (Authors' Collection)

At around 10:40hrs, at 12.200m (40,000ft) and only eight kilometres from the Iranian border, two IRIAF F-4Es underway to attack targets in Iraq, were approaching a Boeing 707-3J9C-tanker escorted by two F-14As,

led by Capt. M. Khosrodad. The Tomcats were flying a race-track pattern around the tanker, with one of them continuously scanning the airspace over the front by its AWG-9 radar. Around 10:45hrs, just as the first

Phantom started receiving fuel from the tanker, the radar onboard Capt. Khosrodad’s F-14A acquired several Iraqi fighters apparently closing from the west and well within the range of the AIM-54 missiles of his

Tomcat.

Despite the standing order not to fly into the Iraqi airspace or leave the tanker unprotected, Capt. Khosrodad decided to attack: he ordered his wingman, whose aircraft was only armed with Sparrows and Sidewinders,

to remain with the Boeing and the two Phantoms; then Capt. Khosrodad headed off west.

Working swiftly, he and his RIO fired two AIM-54As and two AIM-7E-4s in rapid succession, and both were most pleased when they noticed that at least two of their radar contacts disappeared within seconds of each

other: apparently, so they thought, they had just spoiled ‘another Iraqi air raid’….or so they thought.

Meanwhile, although their radar net was supposedly able to track aircraft up to 200km deep inside the Iranian airspace, the Iraqis were completely unaware of the two Iranian Tomcats nearby. The first sign of

something going wrong for Capt. Mousa was when the pilot of one of the escorting Mi-8s – which was flying a couple of kilometres ahead - shouted out a warning that no less than three of escorting fighters (or what

was left of them) were falling out of the skies in flame to their left and right, and that the helicopter carrying generals should make a hard right turn in order to evade the debris.

Seconds later, also one of the MiG-pilots started shouting warnings, saying that they had no clue what had attacked them, but “strongly” suggested the Mi-8 with the generals onboard to leave the area and immediately

turn west! Seeing the wreckage of the downed MiGs falling towards him, Capt. Mousa was in a complete agreement with his colleagues, so he turned around, and the trip to the front by Maj. Gen. Rashid and Lt. Gen.

Mohsen was over before it really started.

Meanwhile, after spending all his medium- and long-range missiles to shoot down one MiG-21 and two MiG-23s within a couple of seconds, Khosrodad returned to the tanker and advised several other F-4s in the

area about the Iraqi fighters: his AWG-9 apparently never detected Iraqi helicopters which flew slow and low between the hills, and several kilometres behind the escorting fighters. The Phantoms indeed tried to

intervene, but before finding the helicopters – about which they did not know any way - they ran into a formation of IrAF Su-22s en route for an attack against Iranian ground troops. A wild dogfight developed, and as

pilots from both sides tried to jettison their air-to-ground weapons, one of the Sukhois was shot down, while the rest of the Iraqi formation fled to the west.

The battle continued without the Iraqi generals, and on the same day, Capt. Ali “Gravedigger” Shafi also got involved in an air combat. While attacking Iraqi armour, he was confronted with one of IrAAC Mi-25 and

SA.342L “hunter/killer” teams. Short on fuel, Shafi and his gunner, WO Ala’i, only managed to fire two long bursts from their 20mm cannon at the Mi-25 before having to disengage and return to their base without

observing the results of their attack. Capt. Shafi and WO Ala’i, however, were killed only five days later, when their AH-1J was shot down by the Iraqi anti-aircraft guns.

By this time, the air-to-ground battle between the Iraqis and Iranians in the area between Eyn-e Khosh and Mandali was over for all purposes. Neither side could be completely satisfied: the Iraqis had suffered

considerable losses in soldiers and equipment, and were forced to pull back from a number of important spots along the border. But, they successfully defended Mandali.

Sacrificing at least two brigades of Basij, the Iranians breached the Iraqi front, but then their attack lost the momentum and no drive closer towards Baghdad was possible any more in the face of the stiff and bitter Iraqi

resistance, even if the Iranians were this time particularly close to achieve a serious breakthrough. The Iraqis had managed to bring forward reinforcements from Baghdad and other parts of the front, and build new

defence lines, as a result two highly promising Iranian offensives lost any chance of success, as the forces and material involved were simply insufficient and overstretched for prolonged battles of attrition.

Certainly the higher leadership of both sides were unable to recognise the importance and success of the airpower, even if it had proved itself once again beyond any doubt: therefore, all the successes and sacrifices of

the Iranian and Iraqi fliers were again in vain. Having had a permission to deploy stronger armoured reserves, which could have exploited the gaps in the Iraqi front, the Iranian Army could – despite the very difficult

terrain and poor roads – have scored a decisive success even with the little air support the IRIAF/IRIAA could offer. Its soldiers were in good spirits, relatively well trained, and willing to fight deep into Iraq. Of course,

with a fully operational IRIAF the Iranian Army could have done much more. Equally, an IrAF deployed to its advantage, instead of being limited to small-scale operations in response to Iranian offensives, could have

tackled the enemy infantry more effectively and crush the Iranian operations in a much shorter time.

Whatever the strategic outcome of the two Iranian offensives undertaken in autumn 1982 was, the results of the use of airpower against armour were humiliating to say for least. Not only that the armour was

deployed mainly for the support of the slow-moving infantry, instead in bold drives through and behind the enemy lines, but the attack helicopters proved exceptionally effective and both the AH-1J and the SA.342L

met expectations of many Western observers, confirming the results of different peace-time testing by the NATO. While the US Army expected an exchange ratio of around 16:1 for the battlefield in the Central Europe,

the Iranians – who used the same tactics and helicopters as the US Army and the USMC – reached much higher ratios, of between 40 and 50:1.

The lightly-armoured French-built SA.342L Gazelle helicopters were typical representatives of the contemporary European ideas about the use of helicopters for anti-tank warfare: their obvious vulnerability proved

these concepts as partially wrong. It was obvious that Gazelle lacked the armour protection for operations in a high-threat environment. Nevertheless, their HOT ATGMs, just like US-supplied TOWs used by the

Iranians, had no particular problems with destroying tanks of any type, regardless if Soviet-built T-55s and T-62s, or US-built M-60A-1s, and British Chieftains. The huge and powerful AT-2-armed Mi-25s obviously

lacked the precision needed for effective anti-tank operations, but were highly efficient in suppressing enemy artillery and anti-aircraft defences, and therefore could be used to support the Gazelles: the East German

concept of the “hunter/killer” teams was therefore proved and confirmed in action.

Despite endless rumours about AIM-54s being "sabotaged by the CIA" or "Hughes technicians" during the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, the

stock of 270 AIM-54s delivered previoiusly remained intact. Sabotaged were only 18 "ready to use" rounds, at the Khatami AB (TFB.8). All of these

were subsequently repaired with help of spare parts purchased clandestinelly from the USA. The IRIAF's F-14 Tomcat fleet was therefore well

suited to continue using the weapon during the whole war against Iraq. This still from a video shows an AIM-54A being loaded under the left

shoulder station of an Iranian F-14. (Authors' Collection)

Post Scriptum

The following is known or can be said about some of the officers and pilots involved in the fighting between Iraq and Iran in the autumn of 1982, as well as eyewitnesses and participants who helped in research that

resulted in this feature.

- IrAAC Capt. Aduan Hassan Yassin went on to fight the Iranians until 1984. During his numerous combat missions with the Mi-25 in 1983, for example, he fired a total of 22 AT-2 ATGMs, scoring only two kills – an

Iranian M-113 APC and a M-60A-1 MBT, and damaging another M-60A-1 – foremost due to the weaknesses of the weapon, the warhead of which was not powerful enough to penetrate the armour of heavier Iranian

tanks. On 14 September 1983 he also claimed one IRIAA AH-1J as destroyed by a salvo of 57mm unguided rockets. During this time, his Mi-25 was damaged no less than nine times by Iranian fire. Finally, on 17 July

1984, together with another pilot of his unit he defected to Syria in two Mi-25s (both of which were taken over by the Syrians and included in the SyAAF).

- IrAAC Capt. S. Mousa continued to fly Mi-8s until March of 1983, when his helicopter was shot down over Iranian positions and he taken prisoner of war. He was released from captivity a couple of years after the

war was over, and subsequently emigrated from Iraq.

- IrAF Capt. Ahmad Salem was decorated for his success against the Iranian Cobra helicopter and subsequently sent to France where he was trained on the Mirage F.1EQ fighters. Later during the war, he also flew

AM.39 Exocet-equipped Mirage F.1EQ-5s in a total of 15 anti-shipping strikes against the Iranian tankers around the Khark Island. In late March 1987, while escorting a Su-22 strike against the oil installations on

Khark, he claimed one IRIAF F-4E as shot down using two R.550 Magic Mk.I air-to-air missiles. His career as fighter pilot came to an abrupt end after his last anti-shipping strike, flown on 15 May 1987, during which

he hit the USN frigate USS Stark (FFG-31) with two Exocets, causing death of 37 US sailors. Despite his and his superiors’ protests, he was grounded and put under observation by the Iraqi secret services, and felt his

life threatened enough by the Iraqi regime to escape the country in 1989.

- East German Capt. Ralf Geschke continued to advise Iraqi Mi-25 pilots and led one of the Mi-25 and SA.342L “hunter/killer” teams of the No.64 Sqn IrAAC until 16 June 1983, when he run out of luck, and his

Hind was intercepted by the F-4E flown by IRIAF Lt. Col. Siavash Bayani, while on a training mission near Taji Army Air Base, in Iraq. Lieutenant-Colonel Bayani, who had already shot down one Iraqi Mi-25 in 1980,

destroyed Capt. Geschke’s Hind by a Sidewinder shot, killing both of its crewmembers.

- IRIAF Maj. Jalal Zandi known as an excellent pilot, but often described as “brazen”, continued his career with IRIAF, in spite of frequent – and fierce – disagreements with Col. Abbas Baba’ie, an officer differently

described as the “mastermind of IRIAF’s capability to keep its F-14-fleet intact”, or simply a “war hero”. There are, however, numerous former IRIAF pilots who not only deny that Baba’ie ever even qualified on F-14s,

but also outright refuse to even mention his name, most likely because of his close cooperation with the clerical regime in Tehran. Zandi survived all his differences with Baba’ie, and numerous air battles with Iraqi Air

Force, to claim a total of nine confirmed (through examination with US intelligence documents released according to FOIA inquiry) and two or three probable kills. It is possible that he scored between eleven and 12

air-to-air victories, thus becoming the most successful F-14-Tomcat pilot ever, and certainly the leading IRIAF ace. He retired only a couple of years ago with the rank of Lieutenant General, but died in a car accident,

in 2001.

- IRIAF Maj. Shahram Rostami also continued a successful career, during which he flew not only F-4 Phantom IIs, but also - mostly - F-14A Tomcats, claiming several more air-to-air kills as well. Already in December

1982, for example, he shot down an Iraqi MiG-25RB that operated at more than 60,000ft and Mach 2.1 over the Persian Gulf, using a single AIM-54A missile fired from a range of more than 70km. He later became

the deputy commander of the IRIAF. Despite many merits and virtues, never really reached the highest brass in the IRIAF, and eventually emigrated from Iran.

Many other Iranian and Iraqi pilots and officers which participated in these battles would not survive the war, while most of the survivors were meanwhile forced to leave their countries. All of them agree with this

account, even if few dispute specific details as given here. The lessons they learned in these bloody battles were largely ignored by the public for different reasons. In the hope that these highly valuable memories will be

saved this way, the authors of this article would like to thank and express gratitude to all those who provided help and advice, especially “The Last of the First” – granted on the strict understanding that, except certain

cases, the individuals would not be named.

A photo from luckier days - and a historical document? This photograph taken in July 1977, should also be showing the then 1st Lt. Abbas Baba'ie

(rear row, first from the left). If this is truth, then Abbas Baba'ie was obviously one of early Iranian pilots qualified on Tomcats. (IIAF-Association

via Authors)

Sources and Bibliography

Although repeatedly asked to this topic we are not ready to reveal any names of (or directly point at) eyewitnesses and participants involved in research related to this article. This is a measure necessary for several