Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kuwait Emergency, 1961

Uploaded by

Josue AlvaradoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kuwait Emergency, 1961

Uploaded by

Josue AlvaradoCopyright:

Available Formats

http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_203.

shtml Go NOV FEB JUN

👤 ⍰❎

73 captures 05 f 🐦

19 Nov 2004 - 7 Feb 2021 2005 2006 2007 ▾ About this capture

*ACIG Home*ACIG Journal*ACIG Books*ACIG Forum *

Articles ARABIAN PENINSULA & PERSIAN GULF DATABASE Latest ARABIAN

ACIG Special Reports

PENINSULA &

PERSIAN GULF

ACIG Database Kuwait Emergency, 1961 Email this article DATABASE

By Tom Cooper & Stefan Kuhn Printer friendly page

ACIG Books, Articles & Media Sep 9, 2003, 05:48 US-Related News from Iraq

Central and Latin America Database Future Development of GCC Air

Forces; Part 2

Europe & Cold War Database Future Development of GCC Air

Forces; Part 1

Former USSR-Russia Database Hard Target: Rolling-Back

Iranian Nuclear Programmes

Western & Northern Africa Database

Shahab 3: an Advanced IRBM

Central, Eastern, & Southern Africa 22 September 2004: Parade in

Database Tehran

Middle East Database Baghdad Impressions

With the 7th Field Hospital in

Arabian Peninsula & Persian Gulf Basrah, Part 2

Database With the 7th Field Hospital in

Kuwait and the Qassem Regime Basrah, Part 1

Indian-Subcontinent Database

Iraqi Super-Bases

Indochina Database In 1899 - long before the huge natural oil resources were discovered in Kuwait - the government of Her Majesty and the Ruler of Kuwait signed an agreement about the defence of the small country. Kuwait remained

under nominal control of the Ottoman Empire until 1918, but was subsequently granted the status of an independent sheikhdom, ruled by the al-Sabah family, with the UK handling its foreign affairs. After further Exhumating the Dead Iraqi Air

Force

Korean War Database negotiations in June 1961 a new treaty was signed, with which the British released Kuwait into independence, but also including an agreement that British forces would assist the Emir al-Sabah, Kuwaiti ruler, if

requested. Second Death of IrAF

Far-East Database 22 September 2003: Iranian

On 25th June 1961 the then Iraqi dictator Abd al-Qarim Qassem unilaterally announced that Kuwait was to be considered Iraqi territory and offered “to liberate the inhabitants of Kuwait”. On the following day some Military Parade

LCIG & NCIG Section Iraqi forces began massing along the border to Kuwait. However the Iraqi military was by far nowhere near the strength it would reach in later years and most of the troops had to make a long march from Baghdad IRIAF Since 1988

down to the southern border of the country. Therefore the Iraqi built-up was very slow. There were several reasons for this situation - most of which can be easily illustrated on the example of the Iraqi Air Force's

ACIG Modeler's Corner condition at the time. US Air-to-Air Victories during

the Operation Desert Storm

Kuwaiti Air-to-Air Victories in

Search Iraqi Air Force in 1961 1990

Go The Iraqi Air Force of the time was in a state of transition. After the bloody al-Rashid coup d’état undertaken on 14 July 1958, during which the young King Feisal III and Crown Prince Abdul Illah of Iraq, together with Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait; 1990

the Iraqi Minister of Defence and a former Prime Minister of Jordan, were assassinated in Baghdad by the elements of the Iraqi military, many officers of the former Royal Iraqi Air Force were imprisoned and normal Persian 'Cats

All Categories

peace-time training schedules – conducted to full RAF-standard - discontinued. Commander of RIrAF at Habbaniyah, Wg.Cdr. Abdul-Razzak, for example, languished in prison from 1958 until 1962. Many other pilots Iraqi Air-to-Air Victories since

Advanced Search have left the country and would never return. 1967

Iranian Air-to-Air Victories

The RIrAF of the 1950s was a well-trained force, operating 12 Vampire FB.Mk.52s, six Vampire T.Mk.55s, and 19 Venom FB.Mk.1s and FB.Mk.50s, as well as 15 Hunter F.Mk.6s. The Hunters were supplied with US

Contributors Log-in financial help in two batches, the first of which – consisting of five aircraft – was delivered in April 1957. The second batch, consisting of ten aircraft, arrived in December 1957. Shortly before the coup in 1958 the

since 1976

USA also supplied five North American F-86F Sabres to Iraq; yet, while the Hunters entered service with the No.1 Sqn, based at Tahmouz/Habbaniyah AB, the Sabres were never to see service in Iraq: they were parked Tanker War, 1980-1988

inside a hangar at al-Rashid AB, and left there for some time before being returned to USA. Iraqi Air Force since 1948, Part

2

Iraqi Air Force Since 1948, Part

1

Fire in the Hills: Iranian and

Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982

I Persian Gulf War: Iraqi

Invasion of Iran, September

1980

I Persian Gulf War, 1980-1988

Kuwait Emergency, 1961

Oman (and Dhofar) 1952-

1979

South Arabia and Yemen,

1945-1995

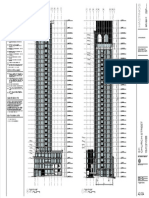

The Iraqi Air Force was a well-trained and highly capable force in the 1950s thanks to acquisition of modern fighters from the UK. In 1953 it received the

first out of 12 deHavilland Vampire FB.Mk.52s, which entered service with the No.5 Squadron, then based at Moascar al-Rashid AB, near Baghdad. (all

artworks by Tom Cooper)

In 1954 and 1956 the then RIrAF was reinforced by acquisition of 19 deHavilland Venom FB.Mk.1s and FB.Mk.5s, which entered service with the No.6

Squadron. The unit was based at Habbaniyah AB (named "Tahmouz" by the Iraqis), and shared this facility with the RAF until 1958, by when also the No.5

Squadron was based there.

Abd al-Qarim Qassem was neither a Ba’athist (the Iraqi nationalist and socialist Ba’ath Party was similar in basic ideology to the Syrian Ba’ath Party, but different in too many details to be described as “same”), but he

was a staunch supporter of the pro-Soviet United Arab Republic. Consequently he was swift to immediately request military assistance from the USSR. In 1958 the first 14 MiG-17Fs as well as some other aircraft were

supplied.

The arrival of the MiG-17s and re-equipment of the No.5 Sqn IrAF with them resulted in a whole “cascade” of re-equipments within the force. The No.1 Sqn was still flying Fury FB.11s, but the No.3 Transport

Squadron was already reformed into three Flights, of which the A-Flight was flying newly-received, Soviet-built Ilushin Il-14 transports, B-Flight the Mi-1 and Mi-4 helicopters, and C-flight British-supplied

Dragonflies. The No.4 Squadron continued flying Hunter F.Mk.6s, while the former mounts of the No.5 Squadron - Venoms - were given to No.6 Squadron after that unit re-equipped with MiG-17Fs. In turn the No.7

Squadron - which was mainly involved in fighting Kurds in the north of the country - was re-equipped with Vampires taken over from the No.6 Squadron. The IrAF thus had to re-train no less but three main fighting

and one transport unit in the period between 1958 and 1961.

Due to being in process of re-qualifying a large number of flying- and ground-crews, and uncertain situation regarding spares supply for its British-built jets, by 1961 the IrAF were therefore not ready for large-scale

operations. The Iraqi Army was in no better condition, then even if it was faster in converting some of its units to Soviet-supplied hardware it lacked training in conduct of large-scale mechanized operations.

This Hunter F.Mk.6 (IrAF serial "403", ex-XK146) was one of 14 ex-RAF aircraft purchased by Iraq with US funding in late 1957. It is seen here already

wearing the fin flash introduced after the coup in 1958.

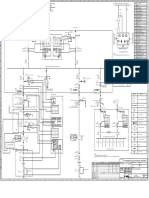

This MiG-17F was one of the first delivered to Iraq, in late 1958. It is seen here wearing the fin flash that was used by the IrAF only between that year and

the next coup in Baghdad, in 1963. Iraq never received as many as 10 MiG-17s as usually reported: in fact, the No.5 Squadron was the only combat unit

known to have ever operated the type, even if a small number of MiG-17Fs and MiG-15UTIs was also in service with the Flying Academy (based at al-

Rashid AB in the early 1960s).

British Intervention

On the contrary, the British reaction was very swift. Under the codename “Vantage” the British had been planning for an intervention in such a situation. This plan included the deployment of additional forces from

the UK, Cyprus and Germany. Technically the UK was well prepared to come to the aid of Kuwait, the problem however was that they could not gain overflight rights from many countries on route, so that a direct

route to the area was not open for the deployment of troops. Already on the next day all British forces in the region were placed on alert. The Centaur-class commando carrier HMS Bulwark (with the 42nd Commando

Battalion embarked) and its escort of three frigates were making a port visit in Karachi, Pakistan. A unit of Royal Marines was already in Bahrain, together with some Army troops, while other units were available in

Bahrain, Sharyah, Aden, Kenya and Cyprus. The RAF had two squadrons of Hawker Hunters in Aden and Nairobi. Heavy transports, light transports and liaison planes in Aden. Additional reserves were based in

Bahrain and Kenya. Facilities in Kuwait were very austere: although one airfield was existent, its installations were very poor and there was no radar. Equally, the port facilities could accept only smaller ships.

Although on the first look the available forces were scattered over a huge area, already on 29th June the British began setting them in motion. HMS Bulwark and her escorts left Karachi and headed for the Persian Gulf

at their best speed. Supply depots in Bahrain were opened and two Hunter Sqns (No.8 208 Sqn) prepared to deploy to Bahrain.

HMS Bulwark, as seen in Naval Base Singapore, few years after the Kuwait Emergency of 1961. (Fleet Air Arm Museum)

On 30th June Kuwait officially appealed for help and a squadron of Hunters was deployed from Eastleigh to Khormaksar, even if Turkey and Sudan refused to grant overflight rights. Already in Bahrain were two

Shackletons MR.2 from No.37 Sqn, and the first planes from No.88 Sqn deployed from RAFG Wildenrath. The staff of the 24th Infantry brigade was flown-in from Kenya using Argonaut and Comet transport planes.

The No.3 Sqn Royal Rhodesian Air Force provided some airlift as well.

RAF Station Sharyah was one of the most important British assets in the Middle East during the 1950s and early 1960s. Seen here on the ramp are (from left

to right): No. 30 Sqn's Beverley, No.152 Sqn's Twin Pioneer, and No.37 Sqn's Shackleton. (Photo: Born in Battle)

On 1st July HMS Bulwark was already deep in the Persian Gulf and the embarked Whirlwind helicopters of 848 NAS began deploying soldiers from 42 Commando to Kuwait. The Hunter fighter-bombers were

deployed to “Kuwait New” airfield, near Farwania, while Britannia transports of No.99 and 511 Squadrons brought troops from 45 Commando Royal Marines and 11th Hussars regiment out of Aden.

In the next days additional units arrived in the area. Four Canberras from No.88 Sqn and eight planes from 213 Sqn landed at Bahrain, while RAF transports flew-in more troops. Until the 4th of July Comets of 216

Sqn and Britannia transports flew in elements of the 2nd Airborne Battalion, while Hastings and Beverly transports hurried to bring in the heavy equipment of the deploying forces. From Kenya the 1st Battalion of the

Royal Inniskillings was also transported to the scene. Also deployed were Canberra PR.7 recce birds. When those forces arrived the first troops had already started to move into Kuwait, so that the pressure on the

installations in Bahrain was reduced.

For the troops in Kuwait however the situation was far from pleasant. After taking position along the Mittla ridge - in the Northwest of the country – they had to cope with temperatures of up to 50°C and sandstorms

that reduced the visibility to less than 300m. A Hunter from No.208 Sqn crashed in this area under such circumstances, killing the pilot. However, most of the deployed forces were accustomed to such circumstances

and eventually there were fewer problems than could be expected. Nevertheless, the British took great care the deployed troops to be constantly rotated between Kuwait and HMS Bulwark, so to get some rest. The

carrier was also acting as a forward deployed station, then it carried a radar with 150km detection range and acted as a communications centre. Especially the last function was critical, as the headquarters of the

operation remained in Bahrain, more than 550km away from Kuwait.

Vast distances also forced the British to improvise with radio communications: when no other solution was found for handling theatre-wide communications signals were relayed by Canberra-bombers between Aden

and Bahrain, while RAF Pembrokes from A-Flight No.152 Squadron were used for liaison duties between Bahrain, Sharyah and Aden. An additional problem was that the RAF planes were using VHF-communications,

while Royal Navy used UHF, so that here also some improvisation was needed in order to enable mutual communication.

Only with the arrival of the larger Illustrious-class carrier HMS Victorious improved the situation considerably. Equipped with Gannet AEW planes and Sea Vixen all-weather interceptors the British forces then gained

a big improvement in situational awareness. This was also added by the 270km-range radar on board the ship, which was further increased by the Gannets.

Finally, on 18th July the RAF was able to put up the first ground-based radar in Kuwait. The SC 787 type could not measure the height of an aircraft, but it did help to improve air traffic control in the region.

Observation party of the 29 Field Regiment Royal Artillery seen while disembarking from an LCT in Kuwait, in 1961. (Photo: IDR via Born in Battle)

After the Iraqi national holiday, on 14th July, passed without any action, the British started feeling more secure and the chance of an armed conflict began to decrease. No Iraqi troop movements south of Basrah had

been noticed. Thus, on 20th July 42 Commando and 2 Para were withdrawn back to Bahrain, while 45 Commando was returning back home to Aden. The Hunters from No.208 Sqn also redeployed to Bahrain.

Remaining British forces withdrew from Kuwait by the end of September.

By late July 1961 HMS Victorious was replaced by HMS Centaur. All transport aircraft had left the area until the beginning of August, and by October 1961 there was barely a trace of the British intervention left. The

last troops left on the 19th October. In the mean time troops from the Arab League had been replacing the British forces to safeguard the freedom and independence of Kuwait. Namely, the Arab League rapidly

countered the British intervention by deploying own forces, intended to guarantee Kuwait's independence of both - Iraq and Great Britain. This Arab League contingent withdrew from Kuwait only following the

overthrow of Iraq's Qassem regime, in February 1963.

Gannet AEW.Mk.3 of NAS 849 A-Flight seen while launching from HMS Victorious. Gannets proved of immense value as early warning aircraft over the

British Task Force in the Persian Gulf and the British forces in Kuwait. (Fleet Air Arm Museum)

Conclusions

Up until today it remains unclear whether the Iraqis were really planning to invade Kuwait, like they had been threatening for decades, or if it was just another threat. The fast British reaction however helped to

stabilise the situation. The British and the Americans did learn a lot about deploying forces over long distances, the associated communications problems and the prearrangement of supplies.

Especially the forward based supply depots in the region proved extremely valuable for the success of the operation and allowed the British to deploy and support large forces over long distances. Especially the US

should use a comparable solution, when Ira invaded Kuwait in 1990.

Another outcome of that crisis was the formation of the Armed forces of Kuwait. More details about this process can be found in the article about the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, in 1990.

For their part, in the aftermath of the crisis the Iraqis immediately started purchasing additional military equipment from the USSR. For example, in 1962 the first out of eventual 40 MiG-19s arrived, followed by the

first 12 MiG-21F-13s and then also a batch of at least 12 Ilushin Il-28 bombers. If these acquisitions indeed came in reaction to the confrontation with the UK over Kuwait, in summer 1961, then it is obvious that the

Iraqis concluded that their available military power at the time was insufficient for an operation in this style. However, in hindsight it must be said that Iraq was never again in a better military or diplomatic position to

take on Kuwait.

Remarks

The team of ACIG.org and several of its correspondents are currently involved in research about the history of the Iraqi Air Force, so also at the times of this emergency. We are therefore certain that sometimes within

2005 we will be able to present a much updated - if not complete - picture of Iraqi intentions and capabilities at the time.

Sources and Bibliography

Except for own research, additional information for this article was kindly provided by Mr. Tom N. Following sources of reference were used as well:

- "AIR WARS AND AIRCRAFT; A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present", by Victor Flintham, Arms and Armour Press, 1989 (ISBN: 0-85368-779-X)

- Born in Battle Magazine No.3, 1979

© Copyright 2002-3 by ACIG.org

Top of Page

You might also like

- Arabian Peninsula & Persian Gulf Database: IRIAF Since 1988Document1 pageArabian Peninsula & Persian Gulf Database: IRIAF Since 1988Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Fire in The Hills - Iranian and Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982Document1 pageFire in The Hills - Iranian and Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Second Death of IrAFDocument1 pageSecond Death of IrAFJosue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Congo, Part 1 1960-1963Document1 pageCongo, Part 1 1960-1963Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Ogaden War, 1977-1978Document1 pageOgaden War, 1977-1978Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- II Ethiopian Eritrean War, 1998 - 2000Document1 pageII Ethiopian Eritrean War, 1998 - 2000Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Sae As 33649a 2005-08Document4 pagesSae As 33649a 2005-08Andr EkmeNo ratings yet

- DX Split Unit - YorkDocument200 pagesDX Split Unit - YorkFaiyaz Bin Mazid AhmedNo ratings yet

- GWCC MapDocument1 pageGWCC Mapapi-110931988No ratings yet

- Atlantic Version: Applicator Data ODocument4 pagesAtlantic Version: Applicator Data OChung LeNo ratings yet

- Lamberti Plumbing LayoutDocument1 pageLamberti Plumbing LayoutNeil ArmstrongNo ratings yet

- SKETCH 022 Tripping MatrixDocument6 pagesSKETCH 022 Tripping MatrixÖzgür Özdemir100% (1)

- List Gambar Penerimaan Klas Rev2Document14 pagesList Gambar Penerimaan Klas Rev2Dolok Joko KenconoNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Version: Revisions CDocument4 pagesAtlantic Version: Revisions Cjuan lopezNo ratings yet

- Water Tank Replacement Big Basin Redwoods State ParkDocument13 pagesWater Tank Replacement Big Basin Redwoods State Parkvaibhav dahiwalkarNo ratings yet

- M007 MML Arc DWG Ucstedu Aa 00007 - Rev4.0Document1 pageM007 MML Arc DWG Ucstedu Aa 00007 - Rev4.0whalet74No ratings yet

- Aerodrome Diagram (Full Airport Layout, Nothing Left)Document1 pageAerodrome Diagram (Full Airport Layout, Nothing Left)Animated VideosNo ratings yet

- Perspective The Site: Land Use and ZoningDocument1 pagePerspective The Site: Land Use and ZoningmarkjosephguanzonNo ratings yet

- VFR LY AD 2 LYVR 2-1-1 en PDFDocument1 pageVFR LY AD 2 LYVR 2-1-1 en PDFVojislav DabicNo ratings yet

- Allorde - A1Document1 pageAllorde - A1flor johnNo ratings yet

- HTTPSWWW - Lvnl.nlmedia4488lvnl Icao 2022c PDFDocument1 pageHTTPSWWW - Lvnl.nlmedia4488lvnl Icao 2022c PDFJens WaldramNo ratings yet

- J1 MergedDocument8 pagesJ1 MergedJervin BragadoNo ratings yet

- Drawings r90 160 Fs Ss Electrical SchematicDocument2 pagesDrawings r90 160 Fs Ss Electrical Schematicingenieria4.0No ratings yet

- G1 MergedDocument12 pagesG1 MergedJervin BragadoNo ratings yet

- Melbourne University - Parkville Campus MapDocument1 pageMelbourne University - Parkville Campus MapЯyuTenNo ratings yet

- 4 Week Temp With MacrooDocument116 pages4 Week Temp With MacrooBander AlkouhlaniNo ratings yet

- Sae As 5202a 2005-05-25Document3 pagesSae As 5202a 2005-05-25Andr EkmeNo ratings yet

- Idoc - Pub Sae As5202 Port DimensionsDocument3 pagesIdoc - Pub Sae As5202 Port DimensionsrjsnelsonjrNo ratings yet

- Ballasted Track DepotDocument1 pageBallasted Track Depotsahilsharma703No ratings yet

- Ball Mill 1 and 2 322-HP-1101 322-PR-PFD-0003 Discharge HopperDocument1 pageBall Mill 1 and 2 322-HP-1101 322-PR-PFD-0003 Discharge HoppernilsNo ratings yet

- Architectural Abbreviations: 0 Days Has Worked This Project 0 0Document46 pagesArchitectural Abbreviations: 0 Days Has Worked This Project 0 0Arshath FleminNo ratings yet

- Marjan Development Program: Tanajib Gas Plant (TGP)Document7 pagesMarjan Development Program: Tanajib Gas Plant (TGP)Maged GalalNo ratings yet

- Ms Leonidas A1Document1 pageMs Leonidas A1Sancho AcbangNo ratings yet

- Swimming Pool and Pump RoomDocument21 pagesSwimming Pool and Pump RoomKriszel TorrelizaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Engineering Design Pumping Station Kapuk Island 2B: Project NameDocument1 pageDetailed Engineering Design Pumping Station Kapuk Island 2B: Project NameAndri Prima RayendraNo ratings yet

- Inbound 6527519127766154016Document15 pagesInbound 6527519127766154016Axel Dave OrcuseNo ratings yet

- SBXQ Arc-Academia Arc 20220811Document1 pageSBXQ Arc-Academia Arc 20220811Davi Ernandes FantiniNo ratings yet

- Daily Progress Report P-132 August - 07 2022 Rev-00Document1 pageDaily Progress Report P-132 August - 07 2022 Rev-00arockiajijinsNo ratings yet

- Line 2 WJDocument1 pageLine 2 WJMahmoud A. HafeezNo ratings yet

- Line 1 WJDocument1 pageLine 1 WJMahmoud A. HafeezNo ratings yet

- Method of Statment CONCRETEDocument7 pagesMethod of Statment CONCRETESyed AtherNo ratings yet

- A-1 PersDocument1 pageA-1 PersAnjo SemaniaNo ratings yet

- 21-07217 - Manalo, Chen Mia D. - Arc 3205 - Midterm PlateDocument5 pages21-07217 - Manalo, Chen Mia D. - Arc 3205 - Midterm Plate21-07217No ratings yet

- Perspective: Site Development Plan Vicinity MapDocument1 pagePerspective: Site Development Plan Vicinity MapByrne JobieNo ratings yet

- Foundation Drawing For DG Enclosure, Switchgear EnclosureDocument9 pagesFoundation Drawing For DG Enclosure, Switchgear EnclosureZobairNo ratings yet

- Vicinity Map: This SiteDocument4 pagesVicinity Map: This SiteDeborah EspirituNo ratings yet

- LY Sup 2011 01 enDocument10 pagesLY Sup 2011 01 enMPBGDNo ratings yet

- Q83-Gujrat - Sas Architecture - Rev8Document13 pagesQ83-Gujrat - Sas Architecture - Rev8azlaanshah12901No ratings yet

- Pages From 2022.10.21 - BPI Church - 100SDDocument1 pagePages From 2022.10.21 - BPI Church - 100SDJay DyerNo ratings yet

- Pages From P24019-30-99-63-1601 - 1-2ggDocument1 pagePages From P24019-30-99-63-1601 - 1-2ggRaeesNo ratings yet

- Cu. Supply CA Supply Cu. SupplyDocument1 pageCu. Supply CA Supply Cu. SupplyKyriakos MichalakiNo ratings yet

- Ifc-Issued For Construction-Rev-0: Ground Floor PlanDocument1 pageIfc-Issued For Construction-Rev-0: Ground Floor PlanemadNo ratings yet

- PSK1-E0000-0000-DDI - Single Line Diagram-Rev-ADocument1 pagePSK1-E0000-0000-DDI - Single Line Diagram-Rev-AAsep SaepudinNo ratings yet

- Tandag A 101Document1 pageTandag A 101Mdrrmo San MiguelNo ratings yet

- Entrance Level (0.00) Building Outdoor Equipotential Bus (S) Termination Conductor With The Loop Earth Electrode ConductorDocument1 pageEntrance Level (0.00) Building Outdoor Equipotential Bus (S) Termination Conductor With The Loop Earth Electrode ConductorsartajNo ratings yet

- S76 C++ - PTM - Mar 2013 (Arrastado) 2Document1 pageS76 C++ - PTM - Mar 2013 (Arrastado) 2Luiz Fernando MibachNo ratings yet

- DRP001 Ouf Gal 940110 K Ecr 001 002 S1Document1 pageDRP001 Ouf Gal 940110 K Ecr 001 002 S1pathanNo ratings yet

- Key Plan: Detail Counter Detail at Window Cill and JambDocument1 pageKey Plan: Detail Counter Detail at Window Cill and JambRichaNo ratings yet

- 9.design Plans and SpecificationsDocument15 pages9.design Plans and SpecificationsJoshua DayritNo ratings yet

- Latin Dragons Airforces Monthly Aug 2007 Ocr Pp6Document6 pagesLatin Dragons Airforces Monthly Aug 2007 Ocr Pp6Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- OA-4M Italeri-InstructionsDocument6 pagesOA-4M Italeri-InstructionsJosue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Fuerza Aérea SalvadoreñaDocument9 pagesFuerza Aérea SalvadoreñaJosue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- 73 InstructionsDocument7 pages73 InstructionsJosue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Alada: EBR EBR Air Air EBR EBR GDA Air AirDocument7 pagesAlada: EBR EBR Air Air EBR EBR GDA Air AirJosue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- II Ethiopian Eritrean War, 1998 - 2000Document1 pageII Ethiopian Eritrean War, 1998 - 2000Josue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Biostar J1800NH SpecDocument7 pagesBiostar J1800NH SpecJosue AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Train Clerk Job Profile: Duties, Responsibilities, and RequirementsDocument1 pageTrain Clerk Job Profile: Duties, Responsibilities, and Requirementsrahul kumarNo ratings yet

- Article 24: Covers Three Distinct Type of Transport DocumentsDocument8 pagesArticle 24: Covers Three Distinct Type of Transport DocumentsJhoo AngelNo ratings yet

- California Politics A Primer 4th Edition Vechten Test BankDocument35 pagesCalifornia Politics A Primer 4th Edition Vechten Test Bankabovehornish.1egar100% (12)

- Fael Aerodrome Chart Ad-01Document1 pageFael Aerodrome Chart Ad-01KHUSHAL BANSALNo ratings yet

- GFB V2 - VNT Boost Controller: (Part # 3009)Document2 pagesGFB V2 - VNT Boost Controller: (Part # 3009)blumng100% (1)

- Legible Sydney Wayfinding Strategy - Part1of2 PDFDocument50 pagesLegible Sydney Wayfinding Strategy - Part1of2 PDFPrakash KumarNo ratings yet

- Data Sheets Bettis GC Series Pneumatic Double Acting Spring Return Actuator Torque Chart Metric Bettis en en 7191530Document34 pagesData Sheets Bettis GC Series Pneumatic Double Acting Spring Return Actuator Torque Chart Metric Bettis en en 7191530rey sarNo ratings yet

- Fiido Electric Bike d4s ManualDocument6 pagesFiido Electric Bike d4s ManualDiego Lorenzo AparicioNo ratings yet

- Safely With Skuld - A Loss Prevention Guide For Seafarers 2023 EditionDocument122 pagesSafely With Skuld - A Loss Prevention Guide For Seafarers 2023 EditionAlexey RulevskiyNo ratings yet

- Road Accidents in India: Dinesh MOHANDocument5 pagesRoad Accidents in India: Dinesh MOHANsom_dsNo ratings yet

- Jotun Paints-Onboard Maintenance Manual-Rig KrathongDocument48 pagesJotun Paints-Onboard Maintenance Manual-Rig Krathongmehanson francisNo ratings yet

- Whale: This Pattern and Dolls Created From This Pattern May Not Be Used For Retail or Commercial Purposes. Thank YouDocument5 pagesWhale: This Pattern and Dolls Created From This Pattern May Not Be Used For Retail or Commercial Purposes. Thank YouMCarmenPardoNo ratings yet

- Solutions Jet FuelDocument4 pagesSolutions Jet FuelkevinNo ratings yet

- Peugeot Partner VP Dag Owners ManualDocument127 pagesPeugeot Partner VP Dag Owners ManualAlex Rojas AguilarNo ratings yet

- đỀ HOÀN CHỈNHDocument9 pagesđỀ HOÀN CHỈNHĐỗ Thảo QuyênNo ratings yet

- TSMO Dash 10 (TM 1-1520-Mi-17-10, Apr 07) PDFDocument406 pagesTSMO Dash 10 (TM 1-1520-Mi-17-10, Apr 07) PDFEften Puften100% (6)

- Holmatro Catalogue 13534Document144 pagesHolmatro Catalogue 13534Forum Pompierii100% (1)

- Manual de Partes - CAT 6060 # DHN60162 (REV3)Document614 pagesManual de Partes - CAT 6060 # DHN60162 (REV3)Waldo Huanchicay100% (1)

- Terex 990Document1,354 pagesTerex 990Hernan Csmaquinaria Reyes60% (5)

- Delkor App Guide v1 Web SDocument72 pagesDelkor App Guide v1 Web Samanda fengNo ratings yet

- ا رارــ ا رــ دــ ـ رـ رـ ـ Final Damage Assessment Report: (A-B) Total Cost / ا اDocument1 pageا رارــ ا رــ دــ ـ رـ رـ ـ Final Damage Assessment Report: (A-B) Total Cost / ا اعبدالرشيد محمدنورالكبيرNo ratings yet

- Torg Eternity The Nile EmpireDocument146 pagesTorg Eternity The Nile Empirevlad86% (7)

- PR 734L, SR 13484Document2 pagesPR 734L, SR 13484yyewin491No ratings yet

- Case - Study VietjetDocument26 pagesCase - Study VietjetTuong NguyenNo ratings yet

- CD 116 Revision 2 Geometric Design of Roundabouts-WebDocument169 pagesCD 116 Revision 2 Geometric Design of Roundabouts-WeblakshenNo ratings yet

- Foton Tunland Auto Spec SheetDocument2 pagesFoton Tunland Auto Spec Sheetmazen foxyNo ratings yet

- Autocar UK - 2023.03.29Document85 pagesAutocar UK - 2023.03.29Diogo Henrique RamôaNo ratings yet

- ISO 26262 OverviewDocument19 pagesISO 26262 OverviewSrinivasan VenkatNo ratings yet

- Marine Propeller Shafting and Shafting AlignmentDocument18 pagesMarine Propeller Shafting and Shafting AlignmentNelson Aguirre BravoNo ratings yet

- E.R. Johnson - American Military Transport Aircraft Since 1925 (2013)Document489 pagesE.R. Johnson - American Military Transport Aircraft Since 1925 (2013)Stotza95% (20)