Professional Documents

Culture Documents

'IHE RELEVANCE OF LINGUI, SI'IC 'IHEDRIES RN 'IHE NWXSIS OF I..I'I'EWlRY TEXTS

Uploaded by

JiaqOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

'IHE RELEVANCE OF LINGUI, SI'IC 'IHEDRIES RN 'IHE NWXSIS OF I..I'I'EWlRY TEXTS

Uploaded by

JiaqCopyright:

Available Formats

183

'IHE RELEVANCE OF LINGUI,SI'IC 'IHEDRIES

rn 'IHE NWXSIS OF I..I'I'EWlRY TEXTS

Mrs J T VCIl Gruenewa1dt

Deparbnentof English, Further Training campus

vista University, Pretoria

To what extent can the application of proce:furesderived fromlinguis-

tic theory l::eof relevance in the analysis of literary texts? '!his is

a controversial question - one that is the focus of muchscrutiny and

debate amongliterary critics and stylisticians.

Michael Halliday's (1971) inquiry into the language of William

Golding's novel 'Theinheritors exemplifiesthe potential that linguis-

tic theories have for elucidating the meaningof literary texts. His

inquiry has, however, evoked conflicting responses which can l::e

regarded as a manifestation of the diverging trends in linguistics and

stylistics concerning not only the nature and location of linguistic

meaning,rot also the mannerin whicha literary text is interpreted.

'The term 'stylistics' denotes .'any analytical study of literature

which uses the concepts and techniques of modernlinguistics' (Fowler,

1973:238). 'The general aim of a stylistic analysis is to establish

the extent to which 'our experienceof a workis in part derived from

its verbal structure' (Traugott and Pratt, 1980:20), or to gain in-

sight into howand whya text meanswhat it does.

2. lHICH r..nmsrrC ~ ARE OF RELEVANCE rn 'lEE ANAIXSIS OF 'lHE

~ OF L:I'l'ffi1IRY TEXTS?

Amongthe linguistic theories that are of relevance in the analysis of

the language of literary texts are those that aim to account for the

manner in whichmeaningis conveyedthroughsyntactic structures. 'The

interdependence of fom and meaning,or the relation l::etween

syntax

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

184

am semantics in the grarronar, is still a current cu;rl problematic issue

in linguistic theory. Muchattention has been given to this question

am various theories have been posite1 to explain the role am status

of the semantic COlTIpOnent

in the grarronar.

How is meaning conveye::l.

through syntactic: structures such as sentences

am clauses? sentence meaning is rrore than just the SlntI of the rnean-

i.n;Js of the lexical items containe::l. within the unit (Traugott am

Pratt, 1980:187). The core of sentence meaning is the proposition

which I refers to entities in the world' acti.n;J or existi.n;J in a sped-

fie relation to one another (Fowler, 1986:69). The semantic nucleus

of the proposition is the predicate which signifies a state or an ac-

tion. The noun phrases associate1with the pre::licate in the sentence'

function in various participant roles such as Actor, Agent, Goal,

Instrument etc. In each case, the participant role is realize::l. by the

semantic function the nOunphrase performs with regard to the nature

of the proceSs expressed in the clause.

Theories which postulate an explanation for the way in which the prop-

ositional content of a sentence relates to entities, states, processes

am actions in the world, constitute a class knc:iYIn

as role theories or

theories of thematic relations1). Various linguists (e g Fillnore

1968; -- Gruber_ 1976;__Jackendoff 1972; Halliday 1967, 1971, 1985) with

differi.n;J theoretical perspectives and stances, have posite1 theories

of thematic relations, aiJnin::Jto account for the relationship between

syntactic structure am seIrantic represent.ation.

According to Traugott am Pratt (1980:191), analysi..n? the relations

that obtain between -the participant roles and the pre::licates in sen-

tences can provide 'exciti.n;J ways of ac:x:ounti.n;J

for aspects of world-

view created in literary works'. In a role structure analysis, the

sentence can be considere::l.to be a 'kin::i of miniature drama expressi.n;J

in language the draJTe that we perceive in the interaction of things

around us with each other and with ourselves' (ibid. 190).

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

185

3• HAI.LID7\Y' S 'IRANSIT.IVI'IY SYSTEH

Halliday IS version of role theory or thematic relations is his system

of transitivity ...mi.ch foms a corrponent of his functional theory of

language. His functional theory is based on the notion that language

has. evolved to =mnunicate humanneeds. A=rdingly, the functional

motivation for language is 'likely to be reflected somewherein the

internal organization of language itself' arrl 'should show up in some

way in an investigation of linguistic structure' (Halliday, 1971:332).

In tenns of Halliday I s functional granunar, the clause is the smallest

unit in ...mi.ch a speaker or a writer's choice fram various semantic

options2) can be observed. Transitivity represents that function of

the clause that expresses the ' reflective experiential aspect of mean-

ing' (Halliday, 1985:101). 'Ibis system specifies 'the different types

of processes that are recognized in the language, arrl the structures

by which they are expressed I. '!he concepts of process, participant arrl

3

circumstance ) are I senantic categories ...mi.ch explain, in the most

general way, haw the phenomenaof the real world are represented in

linguistic structure' (ibid. 102).

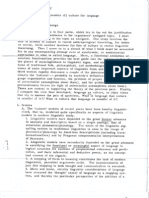

'!he processes constitute a set of semantic options each asso::iate:J.

with a different participant role or set of participant roles, e;

PROCESS

TYPE ASSOCIATED

PARI'ICIPANl'

roLES

MATERIAL (doing)

directed . Agent, Goal .

non-directed . Actor

MENTAL (sensing, perceiving)

directed Actor (senser), Phenomenon

non-directed Actor (senser)

ASQUPITVE(attrihJting) carrier (attrililant)

AttrihJte

(Adapted from Halliday, 1985)

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

186

3. 1 Halliday's iIquiry into the transitivity system of Gol.clin:J'

s llC7IIel.

'1lle :irneri tars

Halliday applies the principles of his transitivity system in his

analysis of the language of Golding's novel The inheritors with the

aim of validating his functional theory of language. In pursui.rq

his analysis, he (1971:339) hopes 'to demonstrate the connection

between the syntactic observations we make about a text aOOthe

nature of the inpact which that text has upon us'.

The inheritors concerns the encounter between two different groups

of prehistoric people aOO the conflict that ensues. I.ok aOOhis

small group of Nean:lerthal 'people' are too helpless to withstaIxi

the rrore evolve:i aOO COlliJE'tent

'tribe'. Eventually the 'people'

are overcome aOO destroye:i by th,e 'tribe'. Halliday (1971:350)

interprets one of the themes of the novel as being 'the inherent

limi.tations of understanding, whet:her cultural or biological, of

Lok aOO his people, aOOtheir conse~ent inability to survive when

confronted with beings at a higher stage of development' •

On the basis of his analysis of th.:! transitivity system of the

clauses of the novel, Halliday fin:l.s that the distriJ:ution of the

various process types an::l their assOciated participant roles is

such that they fall into two groups. COnsequently, he distinguishes

two different narrative styles in the novel which he terms language

A (pp 1-215), that characterizing the world of the 'people', an::l

language C (pp 223-233), that characterizing the world of the

'tribe'.

Halliday selects three passages fram the novel to illustrate aOO

exemplify his role structure findings:

* Passage A (pp 106-107) he regards as being representative of

LanguageA (the narrative of the 'people').

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

187

FRB;2UENCIES

OF TAANSITIVI'IY

CIAUSETYPES

ACTION III

III

Process: intran- transi- 0

c

1_

r:~

u

sitive tive

,5 •..

0 ...•0

,,"0:::

:::

..:.J 0>

c ...•

-'"

.:..l .:..l C.

:: :> ~C>

o or.

C>

E ... ~ •.. •••• III

..:.JI:>

...•

.0

•.. ...C .

0 ~ :>0 ~ ro III

..:.J

.:..>

::

>

0 :; :; U III

00

C

I:>

..:.J

"::0

:.J ...••

E 0 E :)

-0- E

'" 0.:..>

Passage A

human [peoPle 9 1 1 1 12 24

tribe 2 1 1 4

part of b:x3y 2 1 3 2 8

inanimate 4 1 12 3 20

17 3 1 14 16 5 56

Passage B(i)

human (peoPle 4 1 3* 2 1 11

tribe 5 1 1 2 9

part of b:x3y

inanimate 13 1 2 5 2 23

22 1 4 4 9 1 2 43

Passage B(ii)

human [peoPle 13 2 1 2 4 22

tribe

part of b:x3y 3 1 2 6

inaniJrate 3 1 1 2 4 6 2 19

19 3 2 2 7 .. .. 4 ... 8 .. 2 47

Passage C

human [peoPle 1 1 2 4 8

tribe 3 2 5 11 3 11 3 2 40

part of b:x3y 2 1 5 8

inanimate 2 1 3 4 1 11

8 4 6 13 6 15 12 3 67

*including two passives, which are also negative am in which the ac-

tor is not explicit: 'The tree would not be cajoled or persuaded.

(Halliday 1971)

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

188

* Passage B (pp 215-217) consists of two paragraphs. It marks the

transition between the two narratives and conveys the shift in

world-view from that of the 'peopl'e' to that of the 'tribe'.

* Passage C (pp 228-229) represents Language C and exemplifies the

narrative of the 'tribe'.

In his selection of these three passages, Halliday is guide:i by his

otGervation of a prominence, or foregroun:ling, of patterns of in-

transitivity in LanguageA. '!his, he clailns, conveys the defamil-

iarize:i world-view of the 'people' arrl correlates with the thematic

st:n1cture of the novel. Halliday associates this prominence of in-

transitivity in the language of the narrative of the 'people' with

the Prague SChool notion of foregroun:ling (Leech and Short, 1981:

48), namely that patterns of prorni.nence,whether of deviance or

regularity, are artistically motivated. They int:n1de upon the

reader's awareness and invite interpretation.

3.1.1 The transitivity structure of Passage A

Passage A deals with the first encounter between Lok, one of the

'people', and a memberof the 'tribe'.

Halliday identifies 56 clauses in this passage, of which only 4

are transitive, i e contain processes of directed action. Of

these 4 transitive clauses, there is only 1 in which an animate

being :f1,lnctions in the role of .Agentaffecting an external ob-

ject, e q

the man was holding ~ ....

(animate) Process:

-"=-J

Agent directed

action

It is significant that in Passage A, which represents the narra-

tive of the 'people', the only hUI1I3Il

Agent should be c: memberof

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

189

the 'tribe' . Halliday regards this as evidence for his asser-

tion that the role structures in this passage convey the limited

ability of 10k and his 'people' to understand and manipulate

their environment, in contrast to the superior ccmpetence of the

'tribe'.

Another instance of the prominence of intransitivity in this

passage is apparent in the clauses describi.n;J the way in which

10k becomes aware of the tribesman drawi.n;Jhis row and shooti.n;J

an arrCM at hiln. The shooti.n;J of an arrCMwould nonnally be

perceived (and encoded in language) as a Goal-directed process

or action perfonned by a humanAgent. HCMever,in the semantic

structure of the narrative of 10k's world, this action is

expressed as an intransitive self-caused process perfonned by an

i.nanimate subject functioni.n;J in the role of Actor, e g

The stick began to grCM shorter at both ends. Then

Actor Process: l-'.anner I.o::::ation:

non-directed spatial

action (static)

it shot out to full length again.

--

Actor Process: -- Direction Tenporal

non-directed non-terminal adjunct

action

The davmplayi.n;Jof transitivity in this utterance, conveys Lok's

defamiliarized world-view. Because he is incapable of function-

ing in the roie of Agent in his environment, he is unable to

attrihlte Agency to other humans. In Lok's world, i.naniIna1;eob-

jects have as much aniJnacy and volition as do humans. He is

also unable to perceive himself as the Goal of this action.

There is further evidence in the clauses of Passage A that the

theme of the 'people's frustration of the struggle with their

environment' is 'embodied. in the syntax' (Halliday, 1971:354).

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

190

'!his can be observe:i in the iJ;,transitive clauses that contain

potentially transitive verbs. Instead of being associate:l with

a direct object or a Goal, these, processes are folla..>e:i by pre-

positional phrases or cirCLImStantial adjuncts, e 9

~ ... grabbe:i at: the branches

o Process:

non-directe:i

action

Location

The potentially causative function of the verb 'grab' is da..>n-

playe:i in this utterance because it is not associate:l with a

Goal. '!his intransitive use of a normally transitive verb

'creates an atIrosphere of ineffectual activity' with regard to

the actions of the Neanderthal 'pe",ple' (Halliday, 1971:350).

In the 56 clauses in Passage A, half of the noun phrases func-

tioninq as subjects do not denote people - they denote either

i.nani.mateobjects or parts of the body, e 9

His nose exami.ne:i. this stuf

Actor Process: Perceive:

mental phe.nornenc

(his nose) did not like it.

Actor Process: Pe.rceive:i

mental phe!l"lOlllE!IlOn

Clauses in which the Actor associated with a process of mental

perception is a part of the J:x:dyand not an anilnate being are

further support for the claim that there ~s a correlation be-

tween the role structures and the themes of the novel. Halliday

interprets this deviance as a re!flection of the li:mite:l ability

of the '!,€",ple' to perceive and understand their world.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

191

The clauses of Passage A can be said to be characterized by a

lack of processes of directed action associate::l with human

Agents. I The entire transi ti vi ty structure of language A can be

Slm1l'llE!d up by saying that there is no cause and effect' (Halliday

1971:353). In the world of the 'people' there is 'no effective

relation between persons and objects: people do not bring al:out

events in which anything other than they thernselves or parts of

their lxxlies, are iJrplicate::l' (ibid. 354).

3.1.2 The transitivity structure of Passage B

Of the 43 clauses in the first paragraph of Passage B, only 4

are transitive with humanAgents. I.ok functions in the role of

Agent in only one of th~ clauses, e g

~ ... picked up Tanakil

o Process:

directed

action

Goal

Halliday (1971:356) interprets this rare ir.stance of I.ok's Agency

as being an ironic highlighting of the theme of the helplessness

of the 'people' as 'of all the positive actions on his environ-

ment that Lok might have taken, the one he does take is the ut-

terly iJrprobable one of the capture of a girl of the tribe'. It

is this rare act of Agencyin which I.ok affects something or

someone in his external environment that incites the wrath of

the 'tribe' and finally provokes them to destroy h.bn and Fa.

In 2 of the 4 transitive 'clauses in this paragraph, the noun

phrases denoting membersof the 'tribe' function in the role of

Agent, e g

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

192

He (the 'Old man) threw something at Fa.

Agent Process: Goal Directien:

directed terminal

actien motien

Hunters were helding the he)

~ ....

Agent Process: C

directed

actien

~

According to Halliday, the rele structures 'Of this paragraph

underline the theme 'Of the 'pe'Ople's' weakness in c:::anparison

with the 'tribe's' superier adaptation.

In the second paragraph 'Of Passage B, there are 47 clauses. In

'Only 'One'Of these does Lok function in the rele 'Of Agent, e g

It put up a han:i scra1:chej un:3.erits dunless ID::>uth.

Agent Process: Goal Proa~: Locatien : spatial

directed non- (static)

acti'On directed

actien

'!his act 'Of Agency is, however, refleY.ive. I.ok does not affect

anything 'Or anyene ether than hilru;elf. '!he syntax 'Of this utter-

ance iJnplies that '!.ok remains J?cTwerless,master 'Of nothing b..lt

his own J:x::dy' (Halliday, 1971:356), unable to affect anything

external to himself.

3.1.3 '!he transitivity structure 'Of Pas:;;ageC

In Passage C, which characterizes the narrative 'Of the 'tribe',

there is a more even distri.b.ltien 'Of transitive and intransitive

clauses. '!he syntax 'Of this narrative reflects a werld that 'is

'Organized as ours is; 'Or at l,east in a waY that we can rec:o;-

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

193

nize' (Halliday, 1971:356). In the 19 transitive clauses of this

passage, the noun phrases functioning in the role of Agent all

denote anilnate beings, e g

kissed her

o

~

... if she

Process:

directed

action

had saved

Goal

her baby

Agent Process: Goal

directed

action

Youand he gave my child to the devils '" .

Agent Process: Goal

directed

action

'!he role structures of this passage are such that they convey a

world-vie-w in vmic.'l hUl7aTlSare able to understan:l and affect

their environment. '!he processes no longer denote non-directed

ineffectual Irovements but actions that affect other people or

external objects.

In the syntax of the narrative of the 'tribe', parts of the lxx1y

no longer function in the role of Actor a..ss=iated with a mental

.

process. Instead, parts of the lxx1yfunction in the role of

Attribuant with AttribJtes ascribed to them, e q

his teeth were wolf I s teeth

subject Process: AttribJte

Attribuant ascription

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

194

A=rding to Halliday, this is an indication that the 'tribe' are

able to form an awareness of the whole man, to relate and compare

his features to those of other entiti.es in their world. There is

no longer (as is the case in the .Iorld-view of the 'people') a

'reluctance to envisage the ''Y.tloleman" (as distinct from a part

of his J:x:xly) participating in a process in which other entities

are involved' (Halliday, 1971:352).

The world-view of the 'tribe' is one in which humanAgencyand

the relation between cause and effect is understood. In the nar-

rative of the 'tribe' therefore, expE!rienceis encoded in transi-

tive structures with human Agents. Although the 'tribe' are

superior to the 'people', they arE~nevertheless able to credit

the 'people' with the potential for l\gency, e 9

they have given me back a changed 'I\lallIi. i

Agent Process: Recipient Process Goal

directed

action

They cannot follaw us

Agent Process: Goal

directed action

These examples illustrate that 'thl~ tribe's demarxifor ~lana-

tions of things, born of their OIolll more advanced state, leads

them, while still fearfully insisting on the people's weakness

in action, to .ascribe to them supernatural powers' (Halliday,

1971:357).

3. 2 Halliday's role st:ructure claims

In The inheritors, LanguageA, the na:rrative of the' 'people', con-

stitutes the major part of the novel, namely 215 pages. language

C, conveying the narrative of the 'tribe' corrprises only the last

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

195

10 pages of the novel (pp 223-233). The majority of the events in

. the novel are therefore presente:l through the deviant transitivity

patterns characteristic of LanguageA.

Halliday (1971:359) clailns a=rdingly that the functional moti-

vation for linguistic structure is exe!lI'lified in the language of

The inheritors:

'The therre of the entire novel, in a sense, is transitiv-

ity: man's interpretation of his experience of the world,

his understanding of its processes and his orwnparticipa-

tion in them. This is the motivation for Golding's syn-

tactic originality; it is because of this that the syntax

is effective as a modeof meaning.'

The conflicting responses evoke:iby Halliday's irquiry are a reflection

of the cu=ent controversy within the discipline of stylistics, narrely

the dispute between the 'objective' and the 'affective' stylisticians

(Taylor and Toolan, 1984:58).

Fowler (1986:150-151) refers to Halliday's irquiry as a 'pioneering

article'. He (1985:70) maintains that in recent years Halliday's

tra.nSitivity system has becomeof increasing interest to students of

literary stylistics as 'different choices of transitivity structures

in clauses will add up to different world-views, perceptibly different

presentations of the world of fiction'. Traugott and Pratt (1980:219)

describe Halliday's irquiry as 'one of the most interesting studies of

literature from the point of view of role structure analysis'. Leech

and Short (1981:32) .find the analysis 'revealing in the way that it

relates precise linguistic observation to literary effect'.

These positive appraisals are based on the assumption that meaning is

inherent in the language of the text aid that it can be retrieve:i

through an objective study of the linguistic features of that text.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

196

stanley Fish (1973), on the other hand, comments

on Halliday's :inquiIy

in mostlynegative terms. '!he twomajorpoints of criticism he ma}~es

of HallidayI s i.n:IullYare: firstly, that the reasoning on whichhis

transitivity system is based is circular, and secondly, that the

claims and inferences he derives on the basis of his application of

this system are arbitrary. Fish (1973:125) states that 'whena text

is :run through Halliday's machine,its parts are first disassembled,

then labelled, and finally recombine:i

into their original fOI1ll'. In

his view, this is a circular procedurerequiring a great manyoper-

ations yet in the end achievingno gain in understanding. Withregard

to arbitrariness, he (1973:350) claims that Halliday is 'determinedto

confer a value on the fOI1llal

distinctions his machinereads out'.

Fish (1973:129) concedesthat Halliday's i.n:IullYis not entirely with-

out meaning,rot insists that 'the ~lanation for that meaningis not

the capacity for a syntax to ~ress it, rot the ability of a reader

to confer it'. It is in this statementthat the crux of Fish's

reb..lttal, not only of Halliday's i.rquiry, rot also of the methcdsof

stylisticians in general, can be observed.

Fish's rejection of stylistics mustbe seen against the backgroundof

his notion of the nature of linguistic meaningand the role of lin,,""Uis-

tic structure in semanticinterpretation. In his view, meaningexists

solely as an act of interpretation. Meaningis not locate:i within the

structures of a text rot in the ~ience of the reader. He (1970:

123-124) regards meaningas being an 'event', somethingthat 'happens'

through the activities of a reader. It is the reader whohas the sole

authority in constructing a meaningfor a text. In these teI1lIs,the

foregrounde:istructures Halliday observesin the languageof '!he in-

heritors do not 'possess' meaning,they 'acquire' meaningthroughthe

reader's activities (Fish, 1973:143).

Fish (1973 : 144) calls for a newstylistics, whathe teI1lIsan affective

stylistics, in whichthe 'focus of attention is shifte:i fromthe spa-

tial context of a page and its observableregularities to the te1tp:)ral

context of a min:iand its ~iences'.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

197

Is Fish's negative appraisal of Halliday's irqui.ry fair? To what

extent is Fish's notion of li.n:jui.sticmeaning=rnpatible with that of

standard li.n:jui.stic theories subscribedto by stylisticians? Seeki..rq

answers to these questions illustrates the relevance of invoJd.n;J

con-

cepts derived fromlinguistic theory.

In linguistic theory, the difference l::etween

meaningand interpretation

is characterized as the distinction l::etween

sentence and utterance

meaning (Lyons, 1981:140). A sentence is a theoretical construct of

linguistics. Its meaningis depen1enton the meaningof its consti-

tuent lexemesas well as on its graIlUTI3tical

structure. 'Ihe meaningof

an utterance, however, is depen::1ent,

not only on the meaningof its

lexical units and its syntactic structure, l:ut also on additional

information derived fromits context and the hearer or reader's world

of experience. It is the extrali.n:jui.sticinformationthat enables a

hearer or a reader to interpret an utterance or to construct a meaning

for it. Whereasa sentence has a theoretical meaning,an utterance has

a pragmaticor =nmuni.cativefunction.

Fish, in rejectin; the notion that grammaticalconstructions corNey

meaning, and in acknc1wledgin;

only the pragmaticeffect of such con-

structions, is operat~ with a narrow,or limited, notion of what con-

stitutes linguistic meaning.__His criticism of Halliday's inquiJ:yis

therefore neither fair nor valid.

It is, however, theoretical disputes such as this l::etween objective

and affective stylisticians that Irarknewand i.np:>rtantissues in the

discipline that require further investigation. 'Iher~ is a need for

stylistics to. provide a systematic a=unt of the reciprocal

relationship l::etweenthe verbal structure of a text and a reader I s

response to it, or the mannerin whichsyntactic structures not only

enccx:le

meaningrot also prOllptinterpretive activities in a reader.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

198

5. aNCUlSION

Is the application of liJBuistic theory in the analysis of a literary

text merely a futile dismantling of a 'bext, or is it a fruitful exer-

cise promoting a deeper insight into the meaning of the text?

Compiling an inventory of instances of linguistic prominence in a text

is, on its own, not an auta.natic discovery procedure from which a mean-

ing can be read off. 'The instances of prominence need to be motivated,

a=rding to the principles of foregrounding, as being of relevance to

other aspects that contrihlte to the artistic whole, such as the them-

atic meaning or the structuring of experience presented in the text.

The meaning of a text is a rnulti-d.iJnensional affair - manyaspects con-

trihlte to its effect. Its verbal structure is rot one of manyperspec-

tives that need to be considered when assessing its total meaning. So,

too, does the reader's =opetence and experience constitute only a

part of the total meaning of the text.

However, because linguistic theory is systerratic and comprehensive, it

is able to provide a descriptive apparatus which exten::1sto many

levels and aspects of lan;3Uagestructure: and function, such as the syn-

tactic, the semantic, the phonological and the pragmatic. lately, it

has expanded its scope to provide ways of investigating the cohesive

resources of language that operate at a level beyol):ithat of the

sentence, namely the structure and organization of discourse.

As Halliday's irquiry sho:,.,'S, recours;e to an appropriate, linguistic

model can be of valu~ in clarifying or supporting ani:hi.tial intuitive

assessment of a text, as well as in promoting insight into. the way in

which linguistic fonn and artistic function are related.

Acknowledgements

This article is a revised version of part of a thesis sub-

mitted to the Department of General Linguistics at the

University of Stellenbosch in 1990 in partial fulfilment

of the requirements for the M.A. degree in General Linguis-

tics. I wish to acknowledge the contribution of the Depart-

ment, and, in particular, that of Professor 'R.P. Botha,

for his supervision of the work from which this article

resulted.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

199

1) The term 'thematic relations' is derive:! fonn the centrality of the

Theme in Gruber's (1976:38) system of semantic relations in a sen-

tence. The Themeis the entity affected by the verb in the sentence;

it is the entity that urrlergoes the changeof movementor state in the

sentence.

2) Halliday (1985:158) describes the clause as being 'a composite affair,

a combination of three different structures, deriving from distinct

fW'lCtional conponents'• The three structures which he posits as cam-

bining to fonn the clause are transitivity, theme arxi IlOCld. '!heme

structures are those that express 'the organization of the message'.

Mcx::x:1 structures are those that express I interactional rneanin;J'.

3) Halliday (1985:102) refers to the ci.rCl.nnstantialelements as being

'optionally' a part of the clause. The main function of these elements

is to convey the spatial or tenp:>ral location, as well as the manner

or cause, of the process.

Bach, DIunon

arxi Robert T. Harms(eds.)

1968 Universals in linguistic theory. New York: Holt, Rhinehart &

Winston.

C1atJnan,seymur (e:!.)

1971 Literary style A .symposium

... london & NewYork: OXfordUniversity

Press.

1973 Approaches to poetics. New York & london: ColumbiaUniversity

Press.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

200

Fillmore, Charles J.

1968 'The case for case.' In Dn:ronBach arrl Robert T. Hanns (eds.) 1968:

1-90.

Fish, stanley E.

1970 'Literature in the reader Affec:tive stylistics. I NewLiterary

History 2 123-162.

1973 'What is stylistics am Whyare they saying such terrible things

about it?' In seymour O1atman (eel.) 1973:109-152.

F"",ler, Roger

1973 A dictionary of modern critical tenns. Lorrlon am NewYork:

Routledge & Regan Paul.

1985 'PCMer.I In Teun A. van Dijk (ed.) 1985:61-82.

1986 Linguistic criticism. OXford & NewYork: OXford University Press.

Golding, William

1955 The inheritors. Lorrlon & Boston: Faber & Faber.

Gruber, Jeffrey S.

1976 Lexical structures in syntax am senantics. Arnsterdarn: North-

Hollam.

Halliday, Michael A.K.

1967 'Notes on transitivity am theme in En;}lish Part I.' Journal of

Linguistics 3 :- 37-8-1.

1971 'Linguistic function am literary style: An i.n;luiry into the lan-

guage of William Golding's The inheritors.' In seymour O1atman

(ed.) 1971:330-365.

1985 An introduction to functional grarronar. Lorrlon: Edward Arnold.

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

201

Jackendoff, Ray S.

1972 Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. cambridge, Mass.,

etc. : '!he M.LT. Press.

Leech, Geoffrey N. and Michael H. Short

1981 style in fiction : A linouistic intrcx:ruction to English fictional

prose. london & NewYork: lon;pnan.

Lyons, John

1981 I..a.rEuage and lirAuistics. cambridge, etc. cambridge University

Press.

Taylor, Talbot J. and Michael Toolan

1984 'Recent trends in stylistics. I Journal of literary semantics 13

57-79.

Traugott, Elizabeth C. and Mary L. Pratt

1980 Lincruistics for students of literature. NewYork, etc. Harcourt,

Brace, Jovanovich, Inc.

Van Dijk, Teun A. (ed.)

1985 Handbook of discourse analysis Vol. 4. london, etc. Academic

Press.

********

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 25, 1992, 183-202 doi: 10.5774/25-0-81

You might also like

- Mark Twain - The Awful German Language PDFDocument25 pagesMark Twain - The Awful German Language PDFantifoNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech 8Document14 pagesParts of Speech 8Chaloemporn ChantongNo ratings yet

- Ecl Grammar BookDocument98 pagesEcl Grammar Bookhjhj100% (5)

- Virginia Woolf's Old Mrs. Grey Astylistic AnalysisDocument11 pagesVirginia Woolf's Old Mrs. Grey Astylistic AnalysislulavmizuriNo ratings yet

- Fast Track Grammar Review For EFL TeachersDocument66 pagesFast Track Grammar Review For EFL TeachersquedolorquedolorquepenaNo ratings yet

- English 6-Q4-L6 ModuleDocument13 pagesEnglish 6-Q4-L6 ModuleAngelo Jude CobachaNo ratings yet

- Teach Yourself Latin PDFDocument342 pagesTeach Yourself Latin PDFIcaro S.100% (8)

- Sentence ConnectorsDocument10 pagesSentence ConnectorsTatin Farida WahyantoNo ratings yet

- Taranenko Paper 2016 RevisedDocument14 pagesTaranenko Paper 2016 RevisedLarisa TaranenkoNo ratings yet

- CassLogicSenseandSenseRelations PDFDocument13 pagesCassLogicSenseandSenseRelations PDFمحمد العراقيNo ratings yet

- Carston CogpragsDocument17 pagesCarston CogpragsOmayma Abou-ZeidNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2 MergedDocument73 pagesUNIT 2 MergedMariana RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Araby' and Meaning Production in TheDocument40 pagesAraby' and Meaning Production in TheElizNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pragmatics Volume 38 Issue 3 2006 (Doi 10.1016 - J.pragma.2005.06.021) Juliane House - Text and Context in TranslationDocument21 pagesJournal of Pragmatics Volume 38 Issue 3 2006 (Doi 10.1016 - J.pragma.2005.06.021) Juliane House - Text and Context in TranslationAhmed Eid100% (1)

- 3 SFL An OverviewDocument9 pages3 SFL An OverviewCielo LafuenteNo ratings yet

- A FUNCTIONAL MODEL OF LANGUAGE, INTERRELATIONS of Language, Text, and Context, and The Implications For Language TeachingDocument13 pagesA FUNCTIONAL MODEL OF LANGUAGE, INTERRELATIONS of Language, Text, and Context, and The Implications For Language Teachingbela ooNo ratings yet

- 188 400 1 SMDocument17 pages188 400 1 SMUly FikriyyahNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Discourse AnalysisDocument16 pagesApproaches To Discourse AnalysisSaadat Hussain Shahji PanjtaniNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English LiteratureDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Applied Linguistics & English LiteratureLarasati NurputriNo ratings yet

- Jafari - Zahra Metaphors in King LearDocument10 pagesJafari - Zahra Metaphors in King LearMałgorzata WaśniewskaNo ratings yet

- Modern Linguistic Theories and SchoolsDocument59 pagesModern Linguistic Theories and SchoolsJuventus HuruleanNo ratings yet

- TowardsaModelofIntersemioticTranslation FinalDocument13 pagesTowardsaModelofIntersemioticTranslation FinalJoao Queiroz100% (1)

- GehadDocument18 pagesGehadReem EsamNo ratings yet

- Malinowskis Linguistic Theory PaperDocument21 pagesMalinowskis Linguistic Theory PaperRed RoseNo ratings yet

- Speech Act Theory, Speech Acts, and The Analysis of FictionDocument11 pagesSpeech Act Theory, Speech Acts, and The Analysis of FictionHFA Cor UnumNo ratings yet

- Semantic TheoryDocument20 pagesSemantic TheoryAnhar FirdausNo ratings yet

- Transitivity Analysis of Thomas Pynchon's "The Crying Lot of 49Document10 pagesTransitivity Analysis of Thomas Pynchon's "The Crying Lot of 49YudiaNo ratings yet

- Intersemiotic Complementarity: A Framework For Multimodal Discourse AnalysisDocument48 pagesIntersemiotic Complementarity: A Framework For Multimodal Discourse AnalysisJulio Neves PereiraNo ratings yet

- Vivin Agustin (8206112007)Document5 pagesVivin Agustin (8206112007)Mutia OliviaNo ratings yet

- Modern Accounts of Context in Linguistics CritiquedDocument16 pagesModern Accounts of Context in Linguistics CritiquedNata KNo ratings yet

- Hypotactic Structure in English Dessy Kurniasy: IAIN LangsaDocument18 pagesHypotactic Structure in English Dessy Kurniasy: IAIN LangsaSyed Nadeem AbbasNo ratings yet

- Text and Context in Translation PDFDocument21 pagesText and Context in Translation PDFFrançoisDeLaBellevie100% (1)

- Philosophy of LanguageDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of LanguageHind SabahNo ratings yet

- From pre-rep cognition to languageDocument43 pagesFrom pre-rep cognition to language3medenaNo ratings yet

- Prosodic Organization of English Folk Riddles and The Mechanism of Their DecodingDocument14 pagesProsodic Organization of English Folk Riddles and The Mechanism of Their DecodinglarysataranenkoNo ratings yet

- Distributional Semantics in Linguistic and Cognitive Research Article in Italian Journal of LinguisticsDocument3 pagesDistributional Semantics in Linguistic and Cognitive Research Article in Italian Journal of LinguisticsRodrigo SanzNo ratings yet

- Distributional Semantics in Linguistic and Cognitive Research Article in Italian Journal of LinguisticsDocument3 pagesDistributional Semantics in Linguistic and Cognitive Research Article in Italian Journal of LinguisticsRodrigo SanzNo ratings yet

- Semantics: Semantics (from Ancient Greek: σημαντικός sēmantikós)Document8 pagesSemantics: Semantics (from Ancient Greek: σημαντικός sēmantikós)Ahmad FaisalNo ratings yet

- Demystifying Hallidays Metafunctions of LanguageDocument8 pagesDemystifying Hallidays Metafunctions of LanguageBasit KtkNo ratings yet

- Ttransitivity Analysis Representation of Love in Wilde's The Nightingale and The RoseDocument8 pagesTtransitivity Analysis Representation of Love in Wilde's The Nightingale and The RoseDulce Itzel VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Critique of Grice's Pragmatic TheoryDocument11 pagesCritique of Grice's Pragmatic TheoryZara TustraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0271530922000325 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0271530922000325 MainNur islamiyahNo ratings yet

- XI Theories and Schools of Modern LinguisticsDocument62 pagesXI Theories and Schools of Modern LinguisticsDjallelBoulmaizNo ratings yet

- Lexicogrammar Analysis On Skinny Love by Bon IverDocument22 pagesLexicogrammar Analysis On Skinny Love by Bon IverJoyceNo ratings yet

- Language and AffectDocument33 pagesLanguage and AffectMichael KaplanNo ratings yet

- Introduction: Representation and Metarepresentation: María José Frápolli and Robyn CarstonDocument19 pagesIntroduction: Representation and Metarepresentation: María José Frápolli and Robyn CarstonVk Vikas ChandaniNo ratings yet

- The Baboonandthe BeeDocument27 pagesThe Baboonandthe Beeakindele02muchNo ratings yet

- Genre Analysis in The Frame of Systemic 2c8ad15f PDFDocument8 pagesGenre Analysis in The Frame of Systemic 2c8ad15f PDFleonel gavilanesNo ratings yet

- A Glance at Selected Folktale TheoriesDocument5 pagesA Glance at Selected Folktale TheoriesIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- Why Systemic Functional Linguistics Is The Theory of Choice For Students of LanguageDocument12 pagesWhy Systemic Functional Linguistics Is The Theory of Choice For Students of LanguageFederico RojasNo ratings yet

- Silverstein - The Implications of (Models Of) Culture For LanguageDocument20 pagesSilverstein - The Implications of (Models Of) Culture For LanguageadamzeroNo ratings yet

- Semantics L2a (2022 - 2023) 21 (PDF) - 065407-1Document64 pagesSemantics L2a (2022 - 2023) 21 (PDF) - 065407-1theomputu51No ratings yet

- MMMS1713Document8 pagesMMMS1713Ahsani Taq WimNo ratings yet

- Semantic Pragmatic-Speech ActDocument26 pagesSemantic Pragmatic-Speech ActDiah Retno WidowatiNo ratings yet

- Discourse AnalysisDocument214 pagesDiscourse Analysisanhnguyen4work100% (1)

- Reflection and ImaginationDocument12 pagesReflection and ImaginationTzve Yingybert DamblebanNo ratings yet

- Defining Pragmatics: Ella Wulandari, M.A. Wulandari - Ella@uny - Ac.idDocument17 pagesDefining Pragmatics: Ella Wulandari, M.A. Wulandari - Ella@uny - Ac.idPuguh D SiswoyoNo ratings yet

- SFL Theory and Metafunctions in 40 CharactersDocument9 pagesSFL Theory and Metafunctions in 40 CharactersSella RanatasiaNo ratings yet

- Thematic Progression as a Functional Analysis ToolDocument14 pagesThematic Progression as a Functional Analysis ToolFadli Muhamad YulsaNo ratings yet

- Language As Social Semiotic: 1 IntroductoryDocument10 pagesLanguage As Social Semiotic: 1 IntroductoryDiego GruenfeldNo ratings yet

- Halliday'S Standard AccountDocument4 pagesHalliday'S Standard AccounthusnaNo ratings yet

- Situated CognitionDocument21 pagesSituated CognitionCarina PerticoneNo ratings yet

- Stylistic and Linguistic Analysis Using Functional GrammarDocument36 pagesStylistic and Linguistic Analysis Using Functional GrammarDehqani HessamNo ratings yet

- Fatimatuzzahro - 6C - Transitivity ProcessDocument21 pagesFatimatuzzahro - 6C - Transitivity Processde faNo ratings yet

- Claudia Maienborn, Semantics, 99Document27 pagesClaudia Maienborn, Semantics, 99robert guimaraesNo ratings yet

- Cognitive distortion, translation distortion, and poetic distortion as semiotic shiftsFrom EverandCognitive distortion, translation distortion, and poetic distortion as semiotic shiftsNo ratings yet

- Literary StylisticsDocument127 pagesLiterary StylisticsJiaqNo ratings yet

- Stylistics textbook by Paul SimpsonDocument2 pagesStylistics textbook by Paul SimpsonJiaqNo ratings yet

- 01 Wodak CH 013Document34 pages01 Wodak CH 013Wadan KhattakNo ratings yet

- 01 Wodak CH 013Document34 pages01 Wodak CH 013Wadan KhattakNo ratings yet

- Origin and Development of Discourse AnalDocument19 pagesOrigin and Development of Discourse AnalJiaqNo ratings yet

- Modal Verbs ExplainedDocument40 pagesModal Verbs ExplainedCidals Itu FerryNo ratings yet

- English 4 Class AdverbsDocument20 pagesEnglish 4 Class AdverbsEdz RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Tugas Remedial Bahasa Inggris M. Rafi Fahreza X Jasaboga 3Document6 pagesTugas Remedial Bahasa Inggris M. Rafi Fahreza X Jasaboga 3Dhea Amanda RambeNo ratings yet

- SEQUENCE OF TENSESDocument1 pageSEQUENCE OF TENSESOana MariaNo ratings yet

- Intermediate grammar pointsDocument38 pagesIntermediate grammar pointsBichPhuong BuiNo ratings yet

- Lessson Plan PPS PPCDocument2 pagesLessson Plan PPS PPCAnna LatziasNo ratings yet

- Direct and Indirect Speech RulesDocument6 pagesDirect and Indirect Speech RulesAmb SesayNo ratings yet

- New American English For Non-Native SpeakersDocument695 pagesNew American English For Non-Native SpeakersMauricio Mateo MillanNo ratings yet

- Affixation TypesDocument3 pagesAffixation TypesNguyễn Thị Trà MyNo ratings yet

- Test of Irregular Verbs 2 PagesDocument2 pagesTest of Irregular Verbs 2 PagesnalemNo ratings yet

- LESSON EXEMPLAR I ENGLISH 6.docx Jan. 17 2018Document4 pagesLESSON EXEMPLAR I ENGLISH 6.docx Jan. 17 2018Angel Lavadia100% (1)

- Reported SpeechDocument4 pagesReported SpeechvinhekNo ratings yet

- Bound, Derivational Bound, Derivational Bound, Derivational Bound, Inflectional FreeDocument5 pagesBound, Derivational Bound, Derivational Bound, Derivational Bound, Inflectional FreeTrạch Nữ LườiNo ratings yet

- How to Answer Question 3 UPSR ExamDocument34 pagesHow to Answer Question 3 UPSR ExamEsther Ponmalar CharlesNo ratings yet

- Strategies Notefull ReadingDocument4 pagesStrategies Notefull ReadingmahboubeNo ratings yet

- WenaDocument3 pagesWenawEna03No ratings yet

- Collins Cambridge Checkpoint English Coursebook 8 Answers PDFDocument5 pagesCollins Cambridge Checkpoint English Coursebook 8 Answers PDFbelinda chikanda50% (2)

- Sentence Punctuation Patterns and Linking Words and ExercisesDocument3 pagesSentence Punctuation Patterns and Linking Words and Exercisesseanwindow5961No ratings yet

- Key Word Transformation Bank for ESL LearnersDocument2 pagesKey Word Transformation Bank for ESL Learnerseuvelyne samanthaNo ratings yet

- Kirikkale University English Grammar Course ScheduleDocument3 pagesKirikkale University English Grammar Course ScheduleMiraç İtikNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 GramáticaDocument11 pagesUnit 4 GramáticaLILIAN DEL CARMEN RAMIREZ RIVASNo ratings yet

- A2 Grammar - Zero ConditionalDocument4 pagesA2 Grammar - Zero ConditionalSamer dawanNo ratings yet

- 當代中文 vs. 視聽華語主題及語法點對照 PDFDocument20 pages當代中文 vs. 視聽華語主題及語法點對照 PDFlunar89No ratings yet