Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Value Line Contest: A Test of the Predictability of Stock Price Changes

Uploaded by

carminatOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Value Line Contest: A Test of the Predictability of Stock Price Changes

Uploaded by

carminatCopyright:

Available Formats

The Value Line Contest: A Test of Predictability of Stock-Price Changes

Author(s): John P. Shelton

Source: The Journal of Business, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Jul., 1967), pp. 251-269

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2351749 .

Accessed: 20/06/2014 23:57

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Business.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST: A TEST OF THE PREDICTABILITY

OF STOCK-PRICE CHANGES*

JOHN P. SHELTONt

WV THETHERor not an individual,or I. THE CONTEST

a group of investors, can outper- In September, 1965, Value Line, an

form the stock market is a ques- investment advisory service, announced

tion of considerableinterest to profession- a Contest in Stock Market Judgment.

al investors and students of the security Though the Value Line management

markets. On the surface, the question conceived the contest as a promotional

would seem to be fairly easy to answer, device, it provided-as a by-product-

except in the case of private individuals, an unusually good opportunity to test

where it is nearly impossibleto get accu- the stock-selecting ability of a large

rate and complete records.But even pen- number of people. The contest required

sion and mutual funds, whose recordsare that the entrants supply merely their

available for careful measurement,have names and addresses; therefore little is

found the problemnearly insuperable,as known about them, but the participants

is indicated in a number of recent arti- are probably typical of individuals who

cles.' feel they know enough about the stock

In this context, it becomes especially market to make their own investment

interesting to examine the results of a decisions.

very large number of investment choices The contestant was requiredto select

made under the well-defined conditions a portfolio of 25 stocks from 350 that

that governed the 1965-66 Value Line

I See, e.g., Ira Horowitz, "A Model for

contest. In succeeding sections, this Mutual

Fund Evaluation" (Mutual Funds as Investment

paper describes the contest, reviews the Alternatives), Industrial Management Review, Vol.

recent discussions concerning the ran- VI, No. 2 (Spring, 1965); Randolph W. McCandish,

dom-walk hypothesis of stock-price be- Jr., "Some Methods for Measuring Performance of

a Pension Fund," Financial Analysts Journal, Vol.

havior, and then presents and analyzes XXI, No. 6 (November-December, 1965); William

the results attained by the contest's S. Gray, "Measuring the Analyst's Performance,"

18,565 entrants. Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. XXII, No. 2

(March-April, 1966); Frank E. Block, "Risk and

* This study could not have been undertaken Performance," Financial Analysts Journal, Vol.

XXII, No. 2 (March-April, 1966); Peter 0. Dietz,

without financial support from the Ford Foundation,

"Pension Fund Investment Performance-What

made available through the Graduate School of

Method To Use When," Financial Analysts Journal,

Business of the University of Chicago, and Arnold

Vol. XXII, No. 1 (January-February, 1966); John

Bernhard & Co., Inc., which not only provided a part

C. Sherman, "A Device To Measure Portfolio Per-

of the funds used during the study but gave, in a

formance," Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. XXII,

generous and unquestioning manner, complete as-

No. 2 (January-February, 1966); John A. Sieff,

sistance in providing any and all data requested.

"Measuring Investment Performance: The Unit

James Warren, UCLA doctoral student, competent-

Approach," Financial Analysts Journal, XXII, No.

ly programed all the statistical analysis.

4 (July-August, 1966), 93; Richard S. Bower and

t Associate professor of finance, Graduate School J. Peter Williamson, "Measuring Pension Fund Per-

of Business Administration, University of California, formance: Another Comment," Financial Analysts

Los Angeles. Journal, XXII, No. 3 (May-June, 1966), 143.

251

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

252 THE JOURNAL OF BUSINESS

were ranked in categories IV and V by weight to high-priced stocks)-and the

Value Line as of November 26, 1965. contestant was given a percentage score

At that date, Value Line rated 1,072 determinedby dividing ending value by

stocks according to its expectation of beginning value. For example, if the

their probable market performance in average price performanceof the stocks

the next twelve months; it ranked 100 in a portfolio were 90 per cent, it would

in Class I (highest), 259 in Class II mean that if $25,000 had been invested

(above average), 363 in Class III (aver- in the portfolio (placing $1,000 in each

age), 250 in Class IV (below average), stock), the endingvalue wouldbe $22,500,

and 100 in Class V (lowest). In order to or the arithmetic mean of the individual

administer the contest efficiently, each price changes was -10 per cent.

participantwas requiredto print a speci- The Value Line management also se-

fied code number for each stock in addi- lected a list of twenty-five stocks from a

tion to printing the name of each stock universeof one hundredthey had ranked

he selected, and to return his challenge in Class I as of November 26, 1965. The

list to Value Line in an envelope post- Value Line company mailed its list of

markedno later than Sunday, December twenty-six stocks to each contestant in

5. The rules of the contest assumed that an envelope postmarkedprior to Decem-

an equal amount was invested in each ber 5, 1965.

stock at the close of the market Friday, The contestants were competing for a

December 3, 1965. The contestant's en- first prize of $5,000 that would be award-

tries were then keypunched with the ed to anyone whose challenge list of

stocks' names and related codes; in de- twenty-five stocks outperformed Value

termining the accuracy of the entries, Line's list of twenty-five stocks by a

the computer program used by Value greater margin than any other list sub-

Line used the duplicationof information mitted. A second prize of $2,500 was

(i.e., both stock name and code number) awarded for the next best list; third

to double check the selection that was prize was $1,000, and fourth prize was

made. $500. In addition, one hundred more

When the contest ended, the closing prizes of $100 each were provided for

prices as of Friday, June 3, 1966, for contestants whose portfolio's perform-

each of the 350 stocks, adjusted for stock ance exceeded the performanceof Value

splits, stock dividends, and other capital Line's stock list. As it developed, only

changes, were keypunched, and a com- twenty contestants chose portfolios that

puter calculated the percentage change did better than Value Line's, so that not

in the price of each stock in every con- all the prizes potentially available were

testant's portfolio. The total change in earned.

each portfolio was also determined by For our purposes, however, little in-

averaging the percentage changes of all terest attaches to the contest winners

25 stocks. Stating this in another way, alone or to their portfolios, because if

for each portfolio the average price there are "random" elements in stock-

changewas calculated,the averagebeing price behavior, some fraction of port-

based on an equal amount of money in- folios will perform very well, just as

vested in each stock-not an equal num- some others will performvery badly. But

ber of shares of each stock being pur- this may be only the result of chance

chased (which would have given greater factors. The likelihood of such an occur-

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 253

rence can be evaluated only by taking formance measure for the appropriate

into account the performance of the universe.

entire list of entries, not just the best or Furthermore, it is difficult to obtain

the worst. This analysis does so. an unbiased measure of the performance

Contest entrants were self-selected, of a fund, since the fund by its very act

but from a universe that should have in- of taking a position may influence the

cluded a high proportion of the well- performanceof the stocks it buys or sells

qualified investors and advisors. En- and thus affect the very criterion that

trants could have learnedabout the con- was used for measurement.For example,

test from items that appearedin the Wall in February, 1966, the newly created

StreetJournal and other financial publi- Manhattan Fund had nearly $300 mil-

cations; in addition, entry applications lion to invest. Before the year was ended,

were mailed directly to all Value Line its fall in value closely matched the

subscribers, all former Value Line sub- change in the Dow-Jones Industrial Av-

scribers, and others who were on Value erage, but for several months after the

Line's promotionalmailing lists. fund began it fell less than the industrial

A brief review of the problemsencoun- average. It is possible that the purchas-

tered in evaluating performance will ing power of the fund played some part

help to show how unique was the oppor- in sustaining the prices of stocks on

tunity provided by the Value Line con- which it had concentratedpurchases.

test for measuring performance. The Another problem involves the issue of

problemsincludesuch questions as these: risk aversion. The trade-off between

Whatis thespan overwhichperformance lower risk and reduced yield is well ac-

shouldbemeasured?-The commonlyem- cepted in theory and is undoubtedly

ployed calender year is arbitrary and consideredby the funds, but a difficulty

may have no relation to the planning in evaluating performanceis the lack of

horizon the investor has in mind. a precise statement of how much return

How should adjustmentbe made if a a fund is willing to forgo in order to

pensionfund receivesa sizable augmenta- achieve how much stability; the task is

tionjust beforea majorturnin themarket? furthercomplicatedby the lack of agree-

-Some funds receive quarterly or other ment on how to quantify risk.

lumped payments at times over which In view of such problemsit is not sur-

they have no control. prising that researcherswho seek to un-

What yardstick should be used as a derstand the behavior of security mar-

criterion for evaluating performance?- kets have reached few, if any, widely

Among those available are the Dow- accepted conclusions on how investors

Jones Industrial Average, the Utilities have actually performed in relation to

Average, the Rail Average, the Standard

the general market. Nonetheless, it is

& Poor 500 Stock Index, the New York

Stock Exchange Index, the Amex Index, useful to summarizethe previous studies

any of the various over-the-counter in order to provide an intellectual frame

indexes, and the Securitiesand Exchange of referencefor this study.

CommissionIndex. $incetk fund may The early work of Alfred Cowles,using

own stocks that are traded on several ex- forecastspublishedby a small numberof

changes and over the counter, there is professionals, led him to conclude that

no clear, defined,and easy-to-obtainper- there was no "evidence of ability to pre-

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

254 THE JOURNAL OF BUSINESS

dict successfullythe future course of the the funds did not differ appreciablyfrom

stock market."2 what would have been achieved by an

H. K. Wu analyzed data for stock unmanagedportfolio with the same divi-

transactions of corporate insiders and sion among asset types. About half the

concluded that "there is very little evi- funds performedbetter, half worse, than

dence that a definite relationship exists such an unmanagedportfolio."6

between insider transactions and subse- These studies cast doubt on financial

quent price movements in relation to the experts' ability to obtain better-than-

general market trend."3 average results. These doubts are rein-

S. S. Colker evaluated the success of forced by the experience of many aca-

all brokeragehouses' corporateanalyses demic researchers,who have looked for

cited in the Wall Street Journal from patterns or systematic behavior in the

June, 1960,to June, 1961,askingwhether stock market, using sensitive tests for

the stocks analyzed by the brokerage serial correlation,runs and reversals,and

houses performed any better than the periodicity; all of these have failed to

market as a whole. The author conclud- disclose any statistically significantmar-

ed, "the averagebusinessmanis probably ket patterns.

expecting too much in anticipating that Nonetheless, many people doubt that

the stocks to which those in the business U.S. stock-price changes can accurately

of buying and selling securities have in- be characterized as random. Cowles'

vited public attention will appreciate to study, for example, suffered from trying

a markedlygreater extent than the mar- to cope with vague and loosely worded

ket as a whole."4 predictions. Insiders may be buying and

Perhaps the most conclusive study of selling stock for reasons of control, per-

actual performancewas done by Irwin sonal financialrequirements,or based on

Friend and his Wharton colleagues in time spans longer than one or two years.

A Study of Mutual Funds: Investment Colker'sstudy is based on analyses that

Policy and InvestmentCompanyPerform- may or may not be "buy" recommenda-

ance, which concludes that "when ad- tions.

justments are made for this composition Finally, priorstudies have been handi-

[of the portfolios proportions between capped by inadequatenumbersof obser-

bonds,preferredand commonstocks, and vations, which, in the presenceof random

other assets] the averageperformanceby variation and under the usual tests of

significance, have made it difficult to

2 Alfred Cowles, "Stock Market Forecasting,"

Econometrica, Vol. XII, Nos. 3-4 (July-October,

substantiate any other conclusion than

1944); reprinted in E. B. Fredrickson (ed.), Fron- that of random and unpredictableprice

tiers of Investment Analysis (Scranton, Pa.: Interna- changes.

tional Textbook Co., 1965), p. 480. See also Alfred In contrast to the problems that prior

Cowles, "Can Stock Market Forecasters Forecast?"

Econometrica, I (July, 1933), 309-24. studies had to face, many aspects of the

3H. K. Wu, "Corporate Insider Trading Profits Value Line contest made it nearly ideal

and the Ability to Forecast Stock Prices," in H. K. - Irwin Friend, F. E. Brown, Edward S. Herman,

Wu and A. J. Zakon (eds.), Elements of Investments and Douglas Vickers, A Study of Mutual Funds:

(New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1965), p. Investment Policy and Investment Company Perform-

448. ance (prepared for the Securities and Exchange Com-

4 S. S. Colker, "An Analysis of Security Recom- mission by the Wharton School of Finance and Com-

mendations by Brokerage Houses," Quarterly Re- merce [Report of the Committee on Interstate and

viewuof Economics and Business, III (Summer, 1963), Foreign Commerce, House Report No. 2274, 87th

21. Cong., 2d sess., August 28, 1962]), pp. 17-18.

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 255

for evaluating the ability of individuals II. IMPLICATIONS FOR THE RANDOM-

who are somewhat familiar with the se- WALK HYPOTHESIS

curities market to select stocks that Discussions duringthe design and exe-

would outperform the market. For one cution of the researchon this paper made

thing, the Value Line contest had a spe- it clear that some who find statistical

cific time horizonso that all participants analysis of the contest, per se, worth-

knew exactly the period over which they while object if the data from the Value

were being evaluated. Second, the en- Line contest is used to support implica-

trants had riskednothing; thereforethey tions about the validity, or invalidity, of

were seeking to outperformthe market the random-walkhypothesis. The objec-

without constraints that might be im- tions stem from some or all of the follow-

posed by risk limitations. To put it an- ing points: The random-walkhypothesis

other way, price changes were the only relates only to short-term price move-

variable the contestants were trying to ments, and six months is too long a

evaluate. In the third place, they were period to be considered short term; the

not investing money; thus their predic- random-walkhypothesis states that ex-

tions could be tested against a market pected price changes are random, condi-

that was free from self-fulfillingdisturb- tional solely on prior prices and price

ances. Also, for control purposes, it is changes, whereas the contestants un-

extremely useful to have a specified uni- doubtedly took into considerationmuch

verse of securities from which selections more information;and the random-walk

can be made. Such specificationwas not hypothesis should be interpreted to in-

available in other studies. Finally, since clude not just price changes but the sum

dividendsin the short span of six months of price changes plus dividend income.

have a high degree of certainty, the After considerablestudy the author is

major element involved in the discussion convinced not only that differentwriters

about whether the stock market is pre- have differentinterpretationsof the ran-

dictable revolves around the question of dom-walk hypothesis as related to the

price changes, which was the focus of stock market but that the issue can

this contest. eventually be pressed almost to a philo-

The author's interest in the contest sophical, or at least semantic, level pri-

had little to do with the competition be- marily because the concept of random-

tween Value Line and the participants, ness is so hard to quantify. For purposes

but was focused on the unstated "con- of this paper the random-walkhypothe-

test" between the total performanceof sis will be defined as follows:

the entrants and the average perform-

ance of the universeof stocks fromwhich e(P+iIPo,...iPt) e(Pt+iIPt) * (1)

they made their selections. It is valuable In prose, the above equation says that

to have at least one report on precisely tomorrow'sexpected price of a particular

how a large group of people fared in stock, given today's and all previous

selecting stocks, since this adds to the prices, is the same as the expectation of

body of knowledge about securities and tomorrow's price given only today's

investorbehavior.Moreover,it is possible *

6c

price.

to view the results of the contest as hav- 6 The random-walk hypothesiscan also be modi-

ing implications regarding the random- fied to recognizethe effectsof earningsretentionand

walk hypothesis. the existenceof a positiverateof interest.That mod-

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

256 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

Stated narrowly, as above, virtually that information to be non-random in its ap-

all careful empirical studies thus far re- pearance, the period-to-period price changes of

a stock should be random movements, statisti-

ported give strong support to the ran- cally independent of one another. The level of

dom-walk hypothesis.7But these analy- stock prices will, under these conditions, de-

ses are of limited practical interest be- scribe what statisticians call a random walk,

cause they are constrained to utilize and physicists call Brownian motion.8

only price data. In the actual world of With such authority for the position

investing, no one makes decisions on the that the random-walk hypothesis need

basis of only one kind of information. not be confinedto the narrow view that

Whether the analyst be a "chartist," a price changes are conditional on no in-

"fundamentalist," or some other type formation except prior prices, this paper

of practitioner,he considers more infor- specifies one interpretation of the ran-

mation than is allowed in the hypothesis dom-walk hypothesis, as follows, letting

as narrowlydefinedabove.

K, stand for all knowledgepossessed by

The question that is more relevant to the investor today, includingthe current

the real world is whether price changes, price:

given whatever knowledge the investor

AP[Iti Kt] = 0. (2)

uses, behave randomly.Some of the arti-

cles on the random-walkhypothesis ex- This restatement of the random-walk

plicitly cite this largerframeof reference. concept, while it goes beyond the defini-

For example, consider the description tion used by some investigators,is clearly

given by Paul Cootner: of greater interest to the practitionersof

The stock exchange is a well-organized, high- investment and is consistent with the

ly-competitive market. Assume that, in fact, it writings of some academicians.

is a perfect market. While individual buyers or Having established one interpreta-

sellers may act in ignorance, taken as a whole, tion of the random-walkhypothesis, we

the prices set in the marketplace thoroughly

reflect the best evaluation of currently available return to the line of reasoning involved

knowledge. If any substantial group of buyers in testing whether the Value Line con-

thought prices were too low, their buying would testants outperformedthe list of stocks

force up the prices. The reverse would be true fromwhichthey couldmaketheir choices.

for sellers. Except for appreciation due to earn- Readerscan decidefor themselveswheth-

ings retention, the conditional expectation of to-

morrow's price, given today's price, is today's er they think the data are relevant to the

price. random-walkhypothesis.

In such a world, the only price changes that The first question raised in this study

would occur are those which result from new in- is the following: Did the 18,565 contest-

formation. Since there is no reason to expect ants9 select portfolios, on average, that

ification would still be completely consistent with the 8 Paul H. Cootner, "Stock Prices: Random vs.

interpretation presented in this paper. Systematic Changes," Industrial Management Re-

7 See, e.g., the numerous articles in Paul H. Coot- view, III, No. 2 (Spring, 1962), 25. See also Sidney

S. Alexander, "Price Movements in Speculative

ner (ed.), The Random Character of Stock Market

Markets: Trends of Random Walks," Industrial

Prices (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 1964), and

Management Review, II, No. 2 (May, 1961), 7-8,

such articles as Eugene F. Fama, "The Behavior of

and Paul A. Samuelson, "Proof That Properly An-

Stock Market Prices," Journal of Business, Vol.

ticipated Prices Fluctuate Randomly," Industrial

XXXVIII, No. 1 (January, 1965), and Michael D.

Management Review, VI, No. 2 (Spring, 1965), 48.

Godfrey, Clive W. J. Granger, and Oskar Morgen-

stern, "The Random-Walk Hypothesis of Stock 9More than 25,000 people applied for contest

Market Behavior," Kyklos, XVII, Fase 1 (1964), entry blanks; 21,636 submitted selections, but be-

1-30. cause some of them chose stocks outside the universe

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 257

differedfrom the performanceof the 350 a3,50

UP25725 (b)

stocks to which their selection was con-

and

fined by enough to conclude that the UP25 (

resultwas not likely to have happenedby a19 18,565

chance?The null hypothesis being tested

is this: The average score for all contest- The null hypothesis is that:

ants did not differ from the average per- MVL = M19? 3oq9.

formance of the 350 stocks that consti-

Since M19 = Mp26= M350, the null

tute the underlying universe by more

than could be attributed to the effects of hypothesis can also be stated AIVL=

sampling. M350 ? 3r19.

The mathematical and logical basis Let Ho symbolize that the average

for our test is as follows: performanceof the Value Line contest-

ants is within three relevant standard

1. Let the arithmetic mean and the standard deviations of M350;this indicates the null

deviation of the percentage change in prices

for the stocks be designated M350and T35o. hypothesis is supported.Let H1 symbol-

2. Similarly, the mean and standard deviation ize the average Value Line performance

of all possible single portfolios of 25 stocks is more than three orl fromM350;this in-

selected from the universe of 350 will be dicates the null hypothesis is denied.

designated Mp25and UP25. To see the implicationsof accepting or

3. Also, the mean and standard deviation of all

possible means of 18,565 portfolios of twenty- rejecting Ho, note that the process that

five stocks will be designated M19and -19. generates the percentage change in the

(The subscript "19" is to remind the reader

prices can be categorized as (a) random

that this represents the theoretical mean and or (b) non-random.Similarly,the process

standard deviation of a large sample where each by which the contestants selected their

observation in the sample consists of the mean portfolios can be characterized as (a)

of almost 19,000 portfolios of twenty-five stocks random or (b) non-random. (The last

each. The Value Line contest provides one spe-

cific example of such a group of portfolios.)

sentence is primarily an acknowledg-

ment of the virtue of generality;in fact,

4. Finally, let the actual mean of the Value

Line contestants be designated MVL.

it would be extremely unlikely if any

significant number of contestants actu-

Since the mean of the sampling dis- ally did make their choices by a random

tribution of the mean equals the mean process, and an analysis of the actual

of the original population from which selections made reveals that the number

the samples are drawn, we know that of times the various stocks were selected

M350 = MP25 = M19. (a) could hardly be explained by random

selection.)

Similarly, because the standard error These possibilities can be summarized

of the sample mean in random samples in the following matrix:

of size n is equal to the standard devia-

tion of the population divided by the PRICE CHANGES ARE

square root of the sample size, THE SELECTION

PROCESS WAS

Random Non-Random

of 350, did not choose exactly 25 stocks, did not

write the correct code number beside each stock Random. Ho (1) Ho (2)

name, or failed to make the postmark deadline, the

actual number of portfolios evaluated in the contest Non-random . 1.J..... (3) H1 (4)

was 18,565.

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

258 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

If the price changes are random, then enoughof the Value Line contestants had

no selection technique will generate re- access to inside and future information

sults to refute Ho. This is equivalent to to affect the averageresults significantly.

saying that no technique for playing The information they had when they

against a roulette wheel will produce made their selectionswas the sort of past

results significantlybetter than random, or present knowledgethat was generally

even if the bettor uses such blatantly available, and thus likely to have been

non-random techniques as betting only fully accounted for in the prices at the

on red, odd numbers. time the selections were made. Conse-

Similarly, if the selection process used quently, the caveat cited in this para-

by the contestants were random, the re- graph can hardly apply.

sults would be consistentwith Ho regard- Once again it should be emphasized

less of the way price changes occur. that the results of the contest merit

These situations are indicated by cells evaluation for what they contribute to

(1), (2), and (3) of the matrix. our knowledge of the ability of a self-

However, if the research shows that selected groupof investors to outperform

Ho has to be rejected, then it has to be the market. Some may considerthis has

inferred that the investors chose non- implications for the random-walk hy-

randomly and that the price changes of pothesis, but the primarypurposeof this

350 stocks from December, 1965, to paper is merely to report the empirical

June, 1966, were shown to be non-ran- evidence and allow the readerto add his

dom, and by inferencethe whole random- own implications.

walk hypothesis, as interpretedabove, is

III. RESULTS

cast in doubt.

One final caveat about the interpreta- This section presents and analyzes the

tion of the random-walkhypothesis pre- results in the following order: (1) the be-

sented above, which is essentially based havior (mean, median, mode, and meas-

on the analysis in the article by Paul ures of dispersion) of the price changes

Samuelson cited in note 8, is this: The of the 350 stocks available for selection,

view that changes in stock prices behave (2) the performance (mean and disper-

like a random walk does not mean that sion) of 18,565 randomly selected port-

no expert can, with high regularity,make folios of 25 stocks (which can be used as

money by predictingstock-pricechanges. an indication of how randomly selected

He might have foreknowledgeabout, or portfolios would theoretically behave,

be able to predict, something that is given the actual price changes of the 350

highly correlated with the ex post be- stocks), (3) the performance(mean, me-

havior of stock prices. The essence of dian, mode, and measuresof dispersion)

the random-walkhypothesis is that no of the 18,565 portfolios actually selected

one can make consistently successfulpre- by contestants. Items 4-9 reporton tests

dictions about future price changes from of the hypotheses of randomprice change

past or present knowledge alone. Even and random selection followed by tests

if the stock market does change in a ran- and discussionof a number of subsidiary

dom fashion, it would be clearly profit- questions.

able if one could know at least twenty- 1. Behaviorof the 350 stocksavailable

fout hours in advance of all dividenddec- for selection.-The 350 stocks experienced

larations. However, it is doubtful if over the twenty-six weeks an average

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 259

loss in value of 5.957 per cent, or, in also was leptokurtic; that is, it had a

other words, they ended the contest with higher concentration around the mean

94.043 per cent of their market value six and at the extremes than a normal curve

months before. The standard deviation would have. This distribution is consist-

of the percentage price changes for the ent with most studies of stock-price

350 stocks during the six months was changes.

15.93per cent. The rangewas from 202.5 2. Performance of randomly selected

per cent (1 stock, Vasco Metals, more portfolios.-Despite the non-normality

than doubled in price) to 64.7 per cent of the distributionof the individualprice

50

45

40

35

CA

u 30

I-

LL

0 25

w

2 20

z

15

10

0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 2.0 2.1

ENDINGPRICE

BEGINNINGPRICE

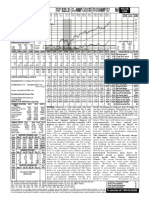

FIG. 1.-Distribution of price changes of 350 stocks

(ConsolidatedCigar lost more than one- changes, the distributionof the perform-

third of its market value during the con- ance of portfolios of 25 stocks selected at

test). The interquartile range was from randomfrom such a group should closely

85.5 to 97.1 per cent. approximate a normal distribution. To

When plotted in a histogram (Fig. 1) demonstrate this, and for comparison

the stock-price changes were unimodal, with the portfolios actually selected by

but not normally distributed.They were contestants, a computer program was

skewed to the right, so that the median written to select a portfolio of 25 stocks

(90.75 per cent) was 21 per cent of one randomly from the 350 involved in the

standard deviation less than the mean. contest and to calculate that portfolio's

The modal value was about 89 per cent. performance; the selected stocks were

The distributionnot only was skewedbut then "replaced"and the processrepeated

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

260 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

many times, until 18,565 such portfolios lated on the computer was within Hf-ol

had been selected.'0The result simulates of 1 per cent of the mean.) Furthermore,

what would have happened if the con- all but 139 out of 100,000 such portfolio

testants' stock selections had been ran- groupings would lie in a range of about

7

dom or if their selections-no matter w of 1 per cent from the mean of the

how artful-had been made from stocks underlying350 stocks. Thus, unless some

whose price changeswere then generated non-randomphenomenonwere involved,

by a truly randomprocess. the mean results of the 18,565 Value

The mean score of the 18,565random- Line contestants should have equaled

ly selected portfolios was 94.05. This the mean of the 350 stocks, namely,

agrees closely, as it should, with the 350 .9404, or at least been in the range from

stocks of 94.04. The standard deviation .9397 to .9411.

of the 18,565 portfolioswas 3.08 per cent In fact, the average score achieved by

(vs. 3.18 per cent, which represents15.93 the 18,565 contestants, .9523, is about

per cent divided by V/25). forty-nine relevant standard deviations

3. Performance of contestants' port- greater than the expected mean. It is

folios.-The foregoinghelps to show how extremely unlikely that a difference as

it can be statistically significant when large as this would have occurred if the

such a large group as our 18,565 contest- price changes during those six months

ants achievesaverageresultsthat diverge were so truly randomthat investor selec-

from the mean of the 350 stocks by even tivity would be of no value. That the

a small amount. It is helpful here to contestants did not select randomly is a

recall the number of different possible necessary, but not a sufficient, explana-

portfolios of 25 stocks that could have tion for the observed difference. If the

been selected, namely, 107.1 X 1036. price changes were truly created by ran-

Then imagine that these were lumped dom behavior, the contestants could not

together by randomly chosen groups of have achieved significantly better-than-

18,565 portfolios each! There would be average results no matter how deliber-

107.1 X 1036f!

ately they made their selections. The

results can only be explained by the

(107.1 X 1036-18,565)! 18,565! additional hypothesis that the price

differentways to collect 18,565portfolios, changes were not generated by a ran-

each containing 25 stocks from the 350. dom process.

Clearly the mean score of all these would The distribution of the 18,565 contest

be extremely close to the mean score of portfolios and the 18,565 randomly gen-

the underlying stocks, and the vast ma- erated portfolios is pictured in Figure 2.

jority would be quite close to that mean. The range of contest portfolio scores was

In fact we would expect that approxi- .8425 to 1.1574. The interquartile range

mately 68 per cent would lie within was .9105 to .9795. The median contest-

.00023 (or i 3 of 1 per cent) on either ants' score was .9479, and the modal

side of the mean. (Remember that the score was in the .9300-.9399 bracket.

score of the one random selection simu- The standard deviation of the 18,565

actual portfolios was 4.39 per cent.

10 The possible number of different 25-stock port-

After-the-fact data may seem obvious

folios selected from a universe of 350 stocks is 350!V

325!25!, which turns out to be 107.1 X 1031,or 107 and perhaps uninteresting. The average

trillion, trillion, trillion. score achieved by the contestants was

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 261

only about 1.2 per cent above average the null hypothesis rejected.... Consid-

results. Is this very noteworthy? The ering the [very low] a priori probability

answer depends on what one expected, of rejectingHo, we do not think it would

which makes it worth quoting the opin- further our objectives to financially sup-

ion of one professionally competent in- port your research."

dividual who was asked to review a re- The Value Line contest showed that

quest for financial support necessary to contestants were able, as of December

underwritethis study. He recommended 5, 1965, to exercise selectivity among

against providing financial support, in- 350 stocks and achieve results that are

dicating, among other things, that the not explainable unless subsequent price

contestants should be characterized as changes were predictableenough to rule

uninformed investors, selecting among out the conclusionthat they could have

stocks they knew little about, using been random.

poorly formulated predictions. He con- 4. Effectof non-normalityof the 350 in-

cluded, "We would be astounded to find dividual stock-pricechanges.-The differ-

FREQUENCY

14.0%

DISTRIBUTIONOF 18,565 PORTFOLIOS

13.0% - REALIZEDIN THEVALUELINECONTEST

12.0% - OF 18,565 SIMULATED

DISTRIBUTION

PORTFOLIOSCREATEDBY RANDOM SELECTION

11.0%

10.0% SIMULATED

9.0%

8.0%

7.0%

6.0% >

\ ~~~~~ACTUAL

5.0%

4.0%

3.0%

2.0%

1.0%

0

.85 .90 .95 1.00 1.05 1.10 1.15

ENDINGPRICE + BEGINNINGPRICE

FIG. 2.-Distribution of actual versus randomly selected portfolios

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

ence of 1.2 per cent between the mean conclusion can be completely accepted.

score of the 350 stocks and the 18,565 Probably the most important concerns

portfolios of 25 stocks appears to be ex- the fact that the contest focuses solely

tremely unlikely to arise from sampling on price changes,giving no credit to divi-

error if the population of all samples of dend income that might have been re-

size 18,565 (where the item observed is ceived during the six months. If it is

the mean performanceof a 25-stockport- assumed 'that for different stocks of

folio) is normallydistributed.It is highly equivalent risk and for a period such as

probable that the sampling distribution six months, total expected return to the

of means of 18,565 portfolios would ap- investor (dividends plus price change)

proximatenormality because of the cen- will be approximately equal, then the

tral-limit theorem, especially in view of lower the expected dividend yield, the

the near-normalityof the sampling dis- more the expected capital gain. Conse-

tribution for means of single 25-stock quently, the selectivity the contestants

portfolios, which would be the universe exhibited may have been only that

from which 18,565 portfolios would be amount necessary to choose stocks pay-

chosen. Data for the randomlygenerated ing low dividends. To test whether the

25-stock portfolios (where n = 18,565) contestants' ability to outperform the

are shown in Figure 3, where the cumu- market was simply associated with an

lative percentage distribution for that avoidance of stocks yielding high divi-

group of portfolios is plotted on proba- dends, a rank correlation was run be-

bility (or normalcurve) graph paper;the tween the frequency with which the

points lie close to a straight line. How- stocks were selected by contestants and

ever, if we are willing to make an as- the estimated yield for the comingtwelve

sumption about the size of the true months, as published in the Value Line

standard deviation for the population of Investment Survey on December 3, 1965.

the means of all possible 18,565 25-stock If the contestants' selectivity consisted

portfolios, we can ignore the issue of of choosing low-dividend yielders, there

whether the distribution is normal and should have been a statistically signifi-

use Tchebycheff's inequality. Assuming cant negative correlation between the

normality, we estimated that the stand- number of times the stock was chosen

ard deviation of the true distribution of and its yield. The actual rank correla-

18,565portfoliosselected from the stocks tion was -.006, which is in no way sta-

in this contest should be close to T2 of tistically significant.This indicated that

1 per cent. But even if it were, in fact, the contestants' performancewas based

as large as 1 of 1 per cent (nearly six on somethingother than dividend avoid-

times greater than would be expected), ance.

then, regardlessof the shape of the dis- 6. Was the contest period representative?

tribution, we would not expect a positive -Another possible objection arises be-

differencefrom the mean as large as 1.2 cause, instead of having a sample of

per cent to be actually achieved by the 18,565 portfolios, there is only a sample

contestants more than one time in two of one contest with a particular set of

hundred. beginning and ending dates. This would

5. Did contestants benefit by avoid- suggest there was some unusual phe-

ing dividends?-Several additional issues nomenon that prevailed as of early De-

have to be evaluated before the above cember,1965,which the contestants took

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 263

into consideration, consciously or not, tion) holds similar contests in the future

but which the market had not already and the contestants' results are repeated-

discounted. If such were the case, then ly tested against the mean performance

the selectivity exhibited in the contest of the stocks in the contest universe. In

would not necessarily appear at other that case, this paper can be viewed as

times. This question can be settled only the first reporton a continuingarea of re-

if Value Line (or some other organiza- search. Fortunately for the field of in-

0

w

rL/

w

0~

w

UI

w

L-

w

U.

0I-I

0

U-

1-

w

a-

.85 .90 .95 1.00 1.05 1. 10

SCORE

FIG. 3.-Normal probabilitygraphfor performanceof randomlygeneratedportfolios

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

264 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

vestment research,Value Line is sched- the generaloutlook for the market at the

uling a second contest for the spring and time the contest began is obtained from

summerof 1967and may conduct further the "Report of the Finance Committee

ones from time to time. of the AmericanEconomic Association,"

7. Werecontestantssimply "playingthe prepared in mid-December, 1965. "The

long shots"?-A final objection might be Finance Committee remainsmildly opti-

that the contestants were not really able mistic as to the trend of general business

to select individual stocks with better- and corporate profits.... Therefore, the

than-average prospects, but that they Committee believes that a fairly aggres-

were able to distinguish stocks with sive investment position is still desirable

greater variance from those with less in spite of the high level of the stock

variance. (Some formulationsof the ran- market and long duration of the present

dom-walkhypothesis would permit such period of business expansion.""

an ability to stratify securities by the In short it is difficult to believe that

amount of their price-changeamplitude.) the sharp downturn in the stock market

This would requirethat the contestants that began in early February, 1966, was

(or at least enough of them to affect the foreseen by many contestants. Further-

results) foresaw the market decline that more, if they chose stocks on the basis

actually occurred and selected stocks of selecting those that would change

that would move (in this case, down) more than the market in either direction

with less amplitude than the average se- (because the rules of the contest did not

curity in the list. This argument, how- penalize exaggerated downside perform-

ever, seems farfetchedin view of the sit- ance, while exaggerated upside per-

uation at the time of the contest. The formancemight win them a prize), then

market had been rising on a broad trend the over-all performanceof the contest-

for nearly three years, with none but the ants should have been worse, not better,

most minor interruptionssince July, and than the average of the 350 stocks, be-

the generaltone of forecastswas optimis- cause the market was lower at the end

tic. It would be impossible to document of the contest than at the beginning.

the claim that most people were optimis- 8. Some measuresof selectivityof con-

tic about the stock market at the time testants' portfolios.-The fact that con-

the contest began, but one piece of evi- testants did not select securities at

dence comes from predictions by thirty- random in making their portfolio selec-

five faculty membersof the UCLA School tions can be proved, though it is hardly

of Business Administrationwho partici-

pated duringthe last week of November, 11 "Report of the Finance Committee," American

1965, in the school's annual Business Economic Review, LVI, No. 2 (May, 1966), 623.

12Mr. Sam Eisenstadt, chief statistician for

Forecasting Conference. Among other

Value Line, commented on this point in a letter to

things, they predicted the Dow-Jones the author: "the market was unique in this six

Industrial Index for 1966; the summa- months' interval. Although Standard & Poor's com-

tion of their forecasts was for the index posite average declined 5.91%, Standard & Poor's

index of low-priced stocks declined 2.31% in contrast

to range between 1,038 and 875, with a to its index of high-priced stocks, which declined

mean value of 960. Since the Dow Indus- 9.78%. To the extent one can classify low-priced

trial stood at 948 on December 1, this stocks as volatile and high-priced stocks as being of

high quality, the market was exceptional because it

was not a bearish forecast. was a declining market in which the low-priced stocks

Another piece of evidence regarding outperformed the blue chips."'

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 265

conceivablethat many contestantswould Line's contest was to evaluate the per-

be so flippant or casual about the contest formance of the contestants against the

as to select stocks randomly. Nonethe- securities from which they had to select.

less, the number of times each security It is clear that the average performance

was selected in the contest was deter- of the contestants was better than could

mined, and the frequencyof actual selec- have been expected if one believes that

tion was compared to the expected fre-

TABLE 1

quency that would be generatedif stocks

PRICE PERFORMANCE OF THE THIRTY-FIVE

were selected randomly. A x2 test was

MOST FREQUENTLY SELECTED STOCKS OVER

applied to see if the actual frequency of THE DURATION OF THE CONTEST

selection differedfrom the expected by a

statistically significantamount. The dif- Ratio of

ference was in fact so great that the No. of

Price at

End of

resulting x2 value was not given in Name of Stock Contestants Contest

tables, the statistical significance being Choosingk

theoStock

Divided by

Price at

beyond the .001 probability. One way to Beginning

illustrate how non-randomthe selections

1. Control Data......... 7,413 .794

actually were is to note the fact that 2. Bell & Howell ........ 5, 817 1.065

when 18,565 portfolios were generated 3. Chrysler Corp..... ... 5,307 .811

4. Cenco Instruments.... 5,016 1.145

randomly, the five stocks that least 5. Caterpillar Tractor.... 4,940 .810

frequently appeared in this random 6. Brunswick Corp....... 4,811 .973

7. Gillette Co........... 4,593 .939

simulation showed up on an average of 8. American Tel. & Tel... 4,480 .880

1,239 times (the lowest one being 1,213 9. Northrop Corp........ 4,372 .775

10. Parke-Davis .......... 4,315 1.016

times). The five stocks that showed up 11. Columbia Broadcasting 4,021 1.320

the most times averaged 1,417 (the most 12. Revlon ............... 3

3,895 1.129

13. Monsanto Chemical... 3,689 .917

frequent being 1,434). These numbers 14. United Nuclear Corp.. 3,659 1.000

suggest the range around the average 15. High Voltage Engineer. 3,621 1.030

16. Curtiss-Wright ....... 3,530 .796

expected selection of 1,326 times that 17. American Enka ....... 3,494 1.020

might occur if stocks had been selected 18. Gulf Oil Corp......... 3,449 .884

19. Texaco .............. 3,338 .889

randomly. In contrast, the five stocks 20. American Photocopy. . 3,293 .897

selected least frequently in the contest 21. Western Union ....... 3,252 .751

22. Singer Mfg ........... 3,090 .917

appearedon the average 108 times (the 23. Royal Dutch Petrol.... 2,994 .892

lowest being 83 times), and the five 24. Transamerica ....... . 2,917 .818

25. Greyhound Corp...... 2,901 .867

stocks selected most frequentlyaveraged 26. E. J. Korvette........ 2.886 .726

5,700 times (the highest being 7,413 27. Gen. Portland Cement. 2,881 .867

28. Rayette, Inc......... . 2,874 .934

times). Furthermore, the actual selec- 29. Lithium Corp......... 2,850 .944

tions showed that 190 securities were 30. Sterling Drug ...... . 2,785 .919

31. Winn Dixie Stores .... 2,773 .886

selected fewer than 1,213 times, which 32. Abbott Labs.......... 2,772 .961

was the least frequent when portfolios 33. W. R. Grace & Co.... 2,665 .834

34. Standard Oil of N.J.... 2,654 .905

were generated randomly, and that 126 35. Electric Storage Bat-

were selected more often than 1,434, tery ................ 2,638 .947

which was the most frequent in the ran-

NOTE.-If all stocks had been chosenrandomly,the expected

dom selection. Table 1 shows data for numberof times each stock would have been selected was 1,326.

The average performanceover the contest period for the ten

the 10 per cent most frequently selected most popular stocks was .921; for the next ten most popular

stocks the performancewas .988; for the thirty-five most fre-

stocks. quently selected stocks the average price performancewas .921,

or a loss of 7.9 per cent. For all stocks in the universe, the aver-

The major goal of this study of Value age price ratio was .940.

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

266 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

stock prices are utterly unpredictable. the contest were used to determine the

To the extent that the random-walkview performanceof the fourteentrend-extrap-

hypothesizes that stock-price changes olated portfolios; for example, the 25

over a periodsuch as six months are com- stocks that had done the best the prior

pletely unpredictable, this study casts six months would, as a portfolio, have

doubt on such a hypothesis. had a score of 96.9 per cent in the con-

TABLE 2 test. The fourteen naively selected port-

folios were then ranked according to

CONSISTENCY OF PERFORMANCE OF FOURTEEN

PORTFOLIOS SELECTED ON BASIS OF PRIOR

their performance during the contest

SIX MONTHS' PERFORMANCE* period. One measure of the consistency

of past and future performance is the

Portfolios Composed rank correlation between the achieve-

of Stocks Whose Score Achieved by ment of the portfolios during the contest

Prior 6-Months' the Portfolio dur- Contest Rank

Performance ing the Contest time and their record for the prior six

Ranked Them: months. This is shown in Table 2; the

1-25 ..9692 5 rank correlation was +.12, which was

25-50 ..9884 3 not statistically significant.

51-75 ..8871 14

76-100 ..9987 1 10. Did contestantsprofitfrom twodays'

101-125 ..9320 7 moreinformation?-The rules of the con-

126-50 ..9079 13

151-7 ..9148 9 test created anotherpossibility that war-

176-200 ..9184 8 rants examination.The contestants were

201-225 ..9099 10

226-250 ..9602 6 permitted to submit entries postmarked

251-275 ..9711 4 no later than Sunday, December5, 1965,

276-300 ..9083 12

301-325 ..9915 2 but their selections were priced as of the

326-350 ..9091 11 close of the market on Friday, December

Mean of: 3. The question arises, did a significant

Top seven port- numberof contestantsutilize information

folios . .9426

Bottom seven that became available over the weekend

portfolios .9384 to select stocks on Sunday that looked

* Rank correlation = + .12.

better than they might have at the close

on Friday? Perhaps the use of two days'

9. Comparisonwith a naive, trend-ex- hindsight might explain how the con-

trapolation technique of selection.-Per- testants outperformed slightly, but sig-

haps the contestants selected their port- nificantly,the universeof stocks to which

folios on the basis of the price perform- their selections were confined.

ance of stocks in the prior six months To test this possibility, the thirty-five

under the assumption that trends tend most frequently chosen stocks were in-

to persist. To test this, the 350 stocks vestigated to see how they performed,

were rankedaccordingto their price per- both over the weekend and over the

formance for the twenty-seven weeks entire period of the contest. If the most

prior to December 3, 1965, and fourteen frequently selected stocks opened on

portfolios were constructed placing the Monday morning,December 6, at prices

25 stocks that did the best in the priorsix that were relatively favorable compared

months in portfolio 1, the 25 stocks that with Friday's close, it could be inferred

ranked-26-50for the prior six months in that contestants took advantage of week-

portfolio 2, etc. The prices at the end of end news items in selecting their stocks.

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 267

As it developed,the thirty-fivemost pop- there should be no significantdistinction

ular stocks in the contest opened on between the 100 stocks in Class I, which

Monday at an average of 2.2 per cent Value Line reservedfor its universe, and

below their Friday's close; this is com- the 350 that were provided for the con-

pared to the Dow-JonesIndustrialAver- testants. Since the standard deviation of

age, which opened 1.6 per cent below its the 350 stocks was approximately16 per

Friday close. By implication, any infor- cent and a standard deviation of a port-

mation obtained on Saturday or Sunday folio of 25 should be close to 2.3 per cent,

had little to do with guiding the most we would expect that Value Line's per-

frequent selections. formance would be within the range

A further point of some interest is 94.04 per cent ? 6.9 per cent 986 times

whether the thirty-five most widely out of 1,000. The actual amount (nearly

chosen stocks outperformedthe universe 17 per cent) by which Value Line out-

during the entire contest, even if they performed the average of the contest-

might have done poorly at the very be- ants' stocks is clearly too great to ex-

ginning. Table 1 lists the stocks in order plain by happenstance. Furthermore,it

of their popularity and shows the ratio is certainly worth noting that the aver-

of each one's price at the end of the age performanceduring that six-month

contest to the openingprice. On average, period for each of Value Line's categories

the thirty-five most popular stocks had was in the proper relationshipaccording

an ending value of 92.1 per cent of their to the company's predictions. This in-

original prices, or a loss of 7.9 per cent, formation is found in Table 3. Even

comparedwith a loss in the total list of when the appropriatevariances are con-

nearly 6.0 per cent. sidered, the performanceof Value Line

The investigation of the performance in the contest or in its general selectivity

of the most frequently selected stocks becomes significant by standard statis-

shows that the contestants' superiorper- tical tests. This conclusion, however,

formance is not explained either by must be qualified by factors that are

knowledgethey may have obtained over beyond the scope of this paper to evalu-

the weekend at the beginningof the con- ate. For one thing, there is the question

test or by the six months' performance of the extent to which Value Line's

of the stocks that ranked in the top 10 good results may have arisen from the

per cent in terms of popularity. phenomena of self-fulfilling predictions.

11. Value Line's performance.-Final- There is no way of knowing how much

ly, in evaluating the predictabilityof the influence Value Line has on the stock

stock market it would be incompletenot market through its subscribers, library

to mention the performance of Value readers, or others who may be affect-

Line's own selections in the contest, al- ed by obtaining its recommendations

though this is difficult to evaluate rigor- secondhandfrom brokersor friends. Fur-

ously. ValueLine's performancesupports thermore,Value Line manages three mu-

the view that stock-price changes have tual funds and quite properlybuys stocks

some degree of predictability, because it for these funds that are given high rank-

is difficult to ignore the fact that Value ing by its advisory service. It may be

Line's scorewas exceededby only twenty that Value Line in actuality has so little

people out of nearly twenty thousand. impact on the market that the perform-

If stock-pricechanges are truly random, ance of its recommendationscan be test-

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

268 THE JOURNALOF BUSINESS

ed against subsequent market perform- conduct a second contest will provide

ance without any allowance for the self- another opportunity to evaluate its

fulfilling aspect of its advice; on the performance.

other hand, it may be that a market

where supply and demand are in close IV. CONCLUSION

balance can be tilted by a significant The evidence from this study indi-

amount when a well-regarded, widely cates that the stock market, during at

distributed advisory service makes rec- least the six months of the contest, had

ommendations. This might be particu- enough elements of predictability that

larly the case when ValueLine announced it is difficultto believe the price changes

TABLE 3

PERFORMANCE OF VALUE LINE'S PORTFOLIO AND STOCK GROUPINGS DURING

THE CONTEST PERIOD DECEMBER 3, 1965-JUNE 3, 1966

Percentage of

Average of S.D. of the Percentage of Stocks that

Percentage Changes Price Changes Stocks that Went up More

in Prices (Per Cent) Rose in Price than the

1,072 Stocks

Value Line defending list of 25 stocks. +10.984 25.25 48.0 68.0

All 100 stocks ranked in Class I ..... ..... + 5.105 19.40 53.0 70.0

All 259 stocks ranked in Class II ....... . + 3.101 19.00 45.6 62.5

All 363 stocks ranked in Class III .- 0.774 17.48 40.5 52.3

All 250 stocks ranked in Class IV ......... - 5.228 15.99 23.2 36.0

All 100 stocks ranked in Class V.......... - 7.779 15.57 14.0 25.0

Average percentage changes of all stocks

ranked I, II, III, IV, and V.- 0.982

Median change of all stocks .............. - 5.00

Change in Dow-Jones Industrial Average.. - 6.16

the 25 stocks it had selected for the con- were generatedrandomly.Since this con-

test, since this contest was unprecedent- clusion differs from most of the prior,

ed in the investment world and the sig- carefully conducted, statistical studies,

nificance of the contest to Value Line's it is worth asking why. Two answers

reputation was so obvious that most suggest themselves. Most of the prior

people would believe the company had

considerableconfidencein the 25 stocks 13 Regarding the question of self-fulfilment, Ar-

nold Bernhard made the following comment in a

it had selected."3 letter to the author: "I can understand how in a

A second qualification arises from the market where trading is evenly balanced, the recom-

consideration, once again, of the repre- mendation of an influential service or the purchase

by mutual funds might tilt the price upward for a

sentatives of the contest period. It is brief time. But have you considered that the stocks

possible that Value Line's performance, Value Line selected for its list were selected from

even though it was apparently statisti- those ranked I before the contest list was published?

If there had been self-fulfillment, it would have

cally superior,was unique to that contest worked against us, it would seem. True, the thrust

period. But it is impressive that Value of a I rank on 100 stocks is not quite so vigorous as

Line was willing to state and publicize a I rank on 25. But still, insofar as our service has

influence, you might want to take into consideration

so widely its expectations and their out- that we did recommend these stocks as I's before

comes. Also, Value Line's willingness to selecting them for our contest; and these ranks, in

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE VALUE LINE CONTEST 269

research was attempting to see if the the requirementfor twenty-five stocks in

market changes demonstrated predict- each portfolio, and the large number of

able patterns conditional on fairly limit- contestants, it was possible in this study

ed amounts of information, such as the to apply extremely precise standardsfor

most recent price change and the current comparingobservedversus expected per-

volume. The contestants, however, used formance.

their full range of informationin making The results of the contest still leave

selections. Second, prior studies, because two questions unanswered:Was the pre-

of the data they used, were not able to dictability peculiar to this segment of

time? Would the marginof predictability

demonstratein a conclusivefashion that have been even greaterif the contestants

a moderateamount of predictabilitywas were somehow limited to investors with

statistically significant. If the price above-averagequalificationsof somesort,

changes are close to random, but not or ones who were motivated to spend

quite, the results would normally fall in more time and thought on their choices?

the range where the evidence of predict- On the first of these questions, at

ability would not be statistically signifi- least, we can hope that more information

cant. In contrast, because of the large will become available from the second

numberof stocks in the contest universe, contest, now in process.The secondques-

tion poses so many problems regarding

practically every case, were in being for weeks prior the determination and measurement of

to the contest. Conversely, the stocks Value Line qualificationsthat it is unlikely that em-

ranked IV and V were so ranked before the contest

started. According to the self-fulfillment theory, that pirical evidence will ever become avail-

should have worked against us, too, because it able; nonetheless, it is hard to believe

should have artificially depressed stocks that con- that the margin of predictive ability

testants were eligible to choose. Much as I should

like to believe it, I doubt that any service can influ- would not be greater for well-informed

ence the market over a period of six months." investors.

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.121 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 23:57:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Sharpe CapitalAssetPrices 1964Document19 pagesSharpe CapitalAssetPrices 1964elianamacedo1720No ratings yet

- Review of Previous Studies on Mutual Fund PerformanceDocument34 pagesReview of Previous Studies on Mutual Fund Performancelohith_reddy86No ratings yet

- Downes 1973Document19 pagesDownes 1973Ranho JaelaniNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument15 pagesUntitledkayal_vizhi_6No ratings yet

- Capital Asset Prices A Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of RiskDocument19 pagesCapital Asset Prices A Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of RiskgoenshinNo ratings yet

- Forecasting in Financial and Sports Gambling Markets: Adaptive Drift ModelingFrom EverandForecasting in Financial and Sports Gambling Markets: Adaptive Drift ModelingNo ratings yet

- Sharpe1964 (Editable Acrobat)Document19 pagesSharpe1964 (Editable Acrobat)julioacev0781No ratings yet

- DFA Case AnalysisDocument28 pagesDFA Case AnalysisMichael JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Capm - Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk - Sharpe WDocument19 pagesCapm - Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk - Sharpe WWilliam Santiago Núñez LópezNo ratings yet

- DFA Case AnalysisDocument28 pagesDFA Case AnalysisRohit KumarNo ratings yet

- MKT Ineffc SSRN Id470161Document42 pagesMKT Ineffc SSRN Id470161athleanNo ratings yet

- Efficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are DeterminedFrom EverandEfficiently Inefficient: How Smart Money Invests and Market Prices Are DeterminedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Patterns of Investment Strategy Aninvestment Strategy and Behavior Among Individual Investorsd Behavior Among Individual InvestorsDocument39 pagesPatterns of Investment Strategy Aninvestment Strategy and Behavior Among Individual Investorsd Behavior Among Individual InvestorsHarvinder Singh100% (1)

- Napier - Identifying Market Inflection Points CFADocument9 pagesNapier - Identifying Market Inflection Points CFAAndyNo ratings yet

- Capital Asset Prices With and Without Negative Holdings: Illiam HarpeDocument23 pagesCapital Asset Prices With and Without Negative Holdings: Illiam HarpeBhargav LingamaneniNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter 3Document23 pages10 Chapter 3Chhaya ThakorNo ratings yet

- Foreword: Equity Markets and Valuation Meth-OdsDocument124 pagesForeword: Equity Markets and Valuation Meth-OdsPaul AdamNo ratings yet

- Mutual Fund Performance and Risk MeasurementDocument21 pagesMutual Fund Performance and Risk MeasurementMark FrellipsNo ratings yet

- Contrarian Investment ExtrapolationDocument11 pagesContrarian Investment ExtrapolationB.C. MoonNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 88.230.57.249 On Sun, 09 Aug 2020 16:02:53 UTCDocument21 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 88.230.57.249 On Sun, 09 Aug 2020 16:02:53 UTCNassima ninaNo ratings yet

- Capital Asset Prices Model (Sharpe)Document23 pagesCapital Asset Prices Model (Sharpe)David PereiraNo ratings yet

- Roman L. Weil's Appreciation of Macaulay's Duration MeasureDocument5 pagesRoman L. Weil's Appreciation of Macaulay's Duration MeasureanotheralternateNo ratings yet

- Investing in Junk Bonds: Inside the High Yield Debt MarketFrom EverandInvesting in Junk Bonds: Inside the High Yield Debt MarketRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- 20.09.investment Valuation and Asset Pricing - Models and MethodsDocument306 pages20.09.investment Valuation and Asset Pricing - Models and MethodsLinhNo ratings yet

- Mutual Fund Industry Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for Investment ProfessionalsFrom EverandMutual Fund Industry Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for Investment ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Fin6310.501.09f Taught by Yexiao Xu (Yexiaoxu)Document8 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Fin6310.501.09f Taught by Yexiao Xu (Yexiaoxu)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Global Shocks: An Investment Guide for Turbulent MarketsFrom EverandGlobal Shocks: An Investment Guide for Turbulent MarketsNo ratings yet

- The Capital Asset Pricing ModelDocument23 pagesThe Capital Asset Pricing ModelDaniel SanchezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Mutual Funds in IndiaDocument4 pagesLiterature Review of Mutual Funds in Indiaanu0% (2)

- Stock Market ControlDocument222 pagesStock Market ControlTCFdotorg100% (2)

- Efficiency of Experimental Security Markets With Insider Information: An Application of Rational-Expectations ModelsDocument37 pagesEfficiency of Experimental Security Markets With Insider Information: An Application of Rational-Expectations ModelsStarletNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Mutual Fund Performance Against Established Performance Benchmarks: A Test of Market EfficiencyDocument15 pagesAnalyzing Mutual Fund Performance Against Established Performance Benchmarks: A Test of Market EfficiencyChandu KamathNo ratings yet

- Auctions Research Opportunities in MarketingDocument17 pagesAuctions Research Opportunities in MarketingMAKURO TANAKA ARCHINENo ratings yet

- Thirty Three Years LaterDocument3 pagesThirty Three Years LaterBill GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Free Cash Flow and Shareholder Yield: New Priorities for the Global InvestorFrom EverandFree Cash Flow and Shareholder Yield: New Priorities for the Global InvestorNo ratings yet

- Investor Avenues and Awareness A Compara PDFDocument13 pagesInvestor Avenues and Awareness A Compara PDFStephina EdakkalathurNo ratings yet

- Investor Avenues and Awareness A Compara PDFDocument13 pagesInvestor Avenues and Awareness A Compara PDFDyna BrandNo ratings yet

- Signalling PDFDocument47 pagesSignalling PDFFábio CastroNo ratings yet

- Initial Public OfferingsDocument11 pagesInitial Public OfferingsferinadNo ratings yet

- 207 Abbey Lane I Lansdale, PA 19446Document6 pages207 Abbey Lane I Lansdale, PA 19446LancasterFirstNo ratings yet

- The Conceptual Foundations of Investing: A Short Book of Need-to-Know EssentialsFrom EverandThe Conceptual Foundations of Investing: A Short Book of Need-to-Know EssentialsNo ratings yet

- Intial Public Offer Icici 2012Document86 pagesIntial Public Offer Icici 2012raghavkaranamNo ratings yet

- The Random Walk TheoryDocument3 pagesThe Random Walk TheorySwanand DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- The Case for Long-Term Value Investing: A guide to the data and strategies that drive stock market successFrom EverandThe Case for Long-Term Value Investing: A guide to the data and strategies that drive stock market successNo ratings yet

- Investors and Markets: Portfolio Choices, Asset Prices, and Investment AdviceFrom EverandInvestors and Markets: Portfolio Choices, Asset Prices, and Investment AdviceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Chapter - Ii Review of Literature & Research MethodologyDocument32 pagesChapter - Ii Review of Literature & Research Methodologypratik0909100% (1)

- Efficient Capital Markets PDFDocument6 pagesEfficient Capital Markets PDFSDPAS100% (1)

- Leibowitz - Franchise Value PDFDocument512 pagesLeibowitz - Franchise Value PDFDavidNo ratings yet

- An Empirical Investigation of Calls of Non Convertible BondsDocument31 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of Calls of Non Convertible BondsZhang PeilinNo ratings yet

- The Theory of Stock Market EfficiencyDocument21 pagesThe Theory of Stock Market EfficiencyMario Andres Rubiano RojasNo ratings yet

- Stick With Strength To Beat August Heat - TheStreetDocument6 pagesStick With Strength To Beat August Heat - TheStreetanalyst_anil14No ratings yet

- The Private Equity Analyst: Guide To The Secondary MarketDocument54 pagesThe Private Equity Analyst: Guide To The Secondary Marketscidmark123No ratings yet

- Handbook of Sports and Lottery MarketsFrom EverandHandbook of Sports and Lottery MarketsRating: 1.5 out of 5 stars1.5/5 (2)

- The Role of Mathematics in Developments of Economic Growth TheoryDocument118 pagesThe Role of Mathematics in Developments of Economic Growth TheorycarminatNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Value Line Standard and Poors and MooDocument6 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Value Line Standard and Poors and MoocarminatNo ratings yet

- 47 CastaterDocument14 pages47 CastatercarminatNo ratings yet

- 3366 9782 1 PBDocument7 pages3366 9782 1 PBcarminatNo ratings yet

- 289-Manuscript File-1197-1-10-20201230Document12 pages289-Manuscript File-1197-1-10-20201230carminatNo ratings yet

- Amzn VLDocument1 pageAmzn VLcarminatNo ratings yet

- Mathematics of Predicting GrowthDocument18 pagesMathematics of Predicting GrowthcarminatNo ratings yet

- ExpguideDocument31 pagesExpguidecarminatNo ratings yet

- Inputs For Real Option Calculations:: Shopify $ 900.00 $ 800.00 113.0 3.00 0.15% 50.0% 75.0%Document6 pagesInputs For Real Option Calculations:: Shopify $ 900.00 $ 800.00 113.0 3.00 0.15% 50.0% 75.0%carminatNo ratings yet

- Price-Implied Expectations (PIE) Inputs: Operating Value DriversDocument12 pagesPrice-Implied Expectations (PIE) Inputs: Operating Value DriverscarminatNo ratings yet

- End Game: Number of Firms Beta Cost of Equity D/ (D+E)Document15 pagesEnd Game: Number of Firms Beta Cost of Equity D/ (D+E)carminatNo ratings yet

- Inputs From Income Statement: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019Document8 pagesInputs From Income Statement: 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019carminatNo ratings yet

- Online Tutorial 7Document6 pagesOnline Tutorial 7carminatNo ratings yet

- Online Tutorial 6Document5 pagesOnline Tutorial 6carminatNo ratings yet