Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Domestic Violence and Young Children

Domestic Violence and Young Children

Uploaded by

Mk AnaisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Domestic Violence and Young Children

Domestic Violence and Young Children

Uploaded by

Mk AnaisCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding the emotional impact of

domestic violence on young children

Victoria Thornton

Young children who live with domestic violence represent a significantly disempowered group.

Developmentally, young children have relatively limited verbal skills and emotional literacy. In addition,

the context created by domestic violence frequently involves an atmosphere of secrecy and intimidation, as

well as reduced emotional availability from children’s main caregivers. Taken together, these factors severely

restrict these young children’s capacity and opportunities to make their voices and needs heard. This

qualitative study gave children who had lived with domestic violence, the opportunity to share their

emotional worlds through projective play and drawing assessments. Eight children aged between 5 and

9-years-old, took part together with their mothers. Transcripts of semi-structured interviews with the mothers

and projective play assessments with the children were analysed using abbreviated, social constructionist

grounded theory. Interpretations from the children’s drawings served to elaborate and validate themes

found in the transcript data. Themes were then linked and mapped into an initial theoretical model of how

domestic violence impacts emotionally on young children. The data gathered shows that domestic violence

generates a range of negative and overwhelming emotions for young children. There is also a concurrent

disrupting impact on the dynamics in the family which undermines the security and containment young

children need to manage and process their emotions. The presence of an attuned adult and age-appropriate

means to communicate is argued to be important in supporting young and traumatised children to share

their emotions. Implications for service planning, clinical practice and educational professionals are

discussed.

Keywords: Domestic violence; young children; emotional impact.

OMESTIC VIOLENCE remains wide- A recent large-scale study, found that 12

D spread in the UK, accounting for 14

per cent of all violent crime (Office for

National Statistics, 2013). Whilst domestic

per cent of under-11s had been exposed to

domestic abuse between adults in their

homes (NSPCC, 2011). Suggestions that

violence can and does occur in all varieties of children can remain oblivious to domestic

intimate and familial relationships, the focus violence taking place in their home, have

of the present study was on women and long since been replaced by a recognition

children who had experienced violence or that children are very much aware of both

abuse by male perpetrators. Data suggest incidents of violence and their aftermath. In

that between 25 to 30 per cent of women a study of 246 children living with mothers

experience domestic abuse over their life- who had been physically assaulted by their

time with a common onset being at the time partners, Abrahams (1994) reported 73 per

of pregnancy, birth or when children are cent of the children as having directly

small (Council of Europe, 2002; Snyder, witnessed assaults on their mothers and 52

1998). In almost half of reported cases, per cent as having seen the resulting injuries.

victims have been abused more than once, Overall, 92 per cent of the children were

with the average length of an abusive rela- found to have been in the same or next

tionship being five years (Chaplin et al., room whilst their mothers were assaulted.

2011; Co-ordinated Action Against Domestic

Abuse (CAADA), 2013). Domestic violence Research review

occurs in all ethnic, social, religious and Appreciating the high prevalence of

educational groups (Martin, 2002). domestic violence in UK homes and recog-

90 Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1

© The British Psychological Society, 2014

Understanding the emotional impact of domestic violence on young children

nising that children are inextricably caught children’s perspective is identical to that of

up in these abusive relationships, brings with adults. Hearing children’s own perspectives

it a need to consider what impact such expe- on their experience has been recognised

riences have on our children. A body of more recently as essential both for research

research, starting in the 1980s, began to and practice in the area of domestic violence

address this question. These early studies (Goddard & Bedi, 2010).

generally used quantitative methodologies, Studies using a more qualitative method-

asking mothers to complete questionnaire ology have directly involved children and

measures about violence that had occurred young people as research participants and

in their homes and symptoms that they had used their own words from interviews to

observed in their children. Reviews and describe and begin to understand their

meta-analyses of these studies (see Kitzmann experience. Some consistent themes reoccur

et al., 2003) conclude that living with across a number of these studies. Children

domestic violence is related to a significant describe domestic violence not as discrete

negative effect on children’s functioning, violent episodes interspersed with times of

with rates of psychopathology being up to calm, but rather as an ever-present atmos-

four times higher among children who have phere, created by controlling behaviour and

lived with domestic violence than among intimidation. In addition, there is the

children from non-violent homes. Reported ongoing threat of actual physical violence

symptoms include externalising problems and harm (Goldblatt, 2003) forcing children

such as aggression and hyperactivity, inter- to be constantly alert and hyper-vigilant

nalising problems such as anxiety and (Epstein & Keep, 1995). Since the atmos-

depression, reduced social competencies phere between violent assaults is described

and higher rates of physical symptoms such by children as equally part of their difficult

as bedwetting, disturbed sleep and failure to experience as the actual violent attacks, it

thrive, particularly among younger children. seems appropriate for research to allow

Children who have been exposed to children to tell us about their everyday

domestic violence were found to have lower family life, beyond specific incidents of

IQs than children from non-violent homes, violence. Children living with domestic

contributing to lower levels of attainment in violence have described feeling isolated and

the classroom. In all of these areas of diffi- ignored (Ericksen & Henderson, 1992) or

culty, a significant positive correlation was struggling to share their concerns due to

found between the duration of the domestic restrictions on their peer relationships

violence experienced and the levels of prob- (Epstein & Keep, 1995) or through fears of

lems reported. not being believed by professionals (McGee,

These quantitative studies made an 2000). These children clearly need help to

important contribution in demonstrating a share their experiences and to feel

clear association between childhood experi- supported in making sense of their

ence of domestic violence and higher rates emotional responses which have been docu-

of psychological distress. However, the focus mented to include fear, helplessness, frustra-

of the methodology on statistical analyses of tion, guilt, shame and confusion (Abrahams,

large samples has been criticised for failing 1994; Epstein & Keep, 1995; Ericksen &

to capture the unique experience of indi- Henderson, 1992; Mullender et al., 2002).

vidual children and for offering little insight Research data reporting children’s own

into the processes through which experi- perspectives and their views on how profes-

encing domestic violence leads to later diffi- sionals could help them is invaluable to

culties. In addition, collecting data from service designers and providers. However,

parents, rather than directly from children the majority of research participants from

themselves, incorrectly assumes that whom this data has been gathered are aged

Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1 91

Victoria Thornton

8 and above. Opportunities have remained children, by hearing directly from them

extremely limited for younger children who about their experiences within their families.

have lived with domestic violence to share Using drawing and projective play allowed

aspects of their experience that feel signifi- these children to share their expectations

cant to them and using methods of commu- and perceptions of family life and relation-

nication that facilitate their self-expression. ships, just as older children and adolescents

have done in previous qualitative studies

Play and drawing with young children who have through interviews and recorded conversa-

experienced domestic violence tions.

It is well documented in the childhood

trauma literature that children who have Method

experienced trauma are likely to struggle to Participants

put their experiences into words. Van der Mother and child pairs or groups were

Kolk (2005) writes: recruited via voluntary sector agencies

‘These children rarely spontaneously working with survivors of domestic violence.

discuss their fears and traumas… They Support workers provided written informa-

tend to communicate the nature of their tion about the study to mothers who were

traumatic past by repeating it in the form asked to discuss the study with their child or

of interpersonal enactments, in their play children and to contact the researcher to

and their fantasy lives.’ opt-in. Eight children, from five families,

Young children who have lived with domestic took part in the study, together with their

violence are a particularly suitable popula- mothers. The children, four boys and four

tion for creative methods of data collection girls, were aged between 5 and 9-years-old.

such as play and art. Their developmental All of the children had at least one sibling

stage leaves them less able to verbally convey living in the same house. For two of the fami-

their experiences, particularly since memo- lies, several siblings fell within the age range

ries of traumatic events at any age are of the study and all took part. Mothers were

commonly stored in affective, non-declara- aged between 24 and 42-years-old. Their

tive memory making them less accessible for relationships with their violent partners had

verbal recall (Moore, 1994). all ended between six months and two years

Whilst there are several books that report prior to the study. All participants were white

on clinical work using art with children who British.

have experienced domestic violence, docu-

mented research using art with this popula- Ethical considerations

tion is extremely limited. Similarly, although The study aimed to truly hear children’s own

there are a number of published research perspectives on their experiences and treat

studies that have used the structured play them as active participants in the research

scenarios of story-stems to collect data with process. Researching with young children

children who have experienced domestic who have already lived through distressing

violence, the overall research designs have life experiences raises issues of possible

been quantitative, using predefined scoring exploitation or harm caused by insensitive

procedures to code story stem responses and research methods. However, denying young

compare these with scores on questionnaire children the opportunity to make their

measures such as children’s well-being or voices and needs heard has the potential to

maternal psychopathology (see Grych et al., lead to harm of a different kind. Over-

2002; Huetteman, 2005; Shamir et al., 2001). protecting children from research means

The present study had a different aim; to that they do not have the opportunity to

build an understanding about the emotional inform and shape the services and interven-

impact of domestic violence on young tions created by adults and intended to be

92 Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1

Understanding the emotional impact of domestic violence on young children

supportive (Mullender et al., 2002). With for the specific purpose of measuring

this dilemma in mind, the present research children’s internal mental representations of

study gave particular consideration to ethical attachment figures. There is a manual to

issues in order to ensure that young children guide the use of a numerical coding system

could provide research data, whilst (Hodges et al., 2004). However, for the

remaining protected from potential harm. current study the story stems were used only

Consent was sought independently from to provide structured play prompts that

each mother and child. Information packs could be replicated with each of the

about the study were produced for mothers children. The task provided an engaging and

and separately for children. The children’s non-threatening means through which

packs used age appropriate language and children could express their expectations,

pictures to explain why the study was being feelings and perceptions in displaced form

done and what participation would involve. and using both verbal and non-verbal

Consent from a mother did not assume communication.

consent from her child. It was made clear Each child also completed two drawing

that the decision to participate would have assessments; the Kinetic Family Drawing

no influence on service provision. Both (Burns & Kaufman, 1972) and the Human

mothers and children were given the option Figure Drawing (Koppitz, 1968). Both of

to withdraw from the study at any time. Time these tasks allow children to depict issues or

was taken at the beginning of each child’s feelings that feel most important to them,

meeting with the researcher to build trust without feeling pressurised to respond to

through free play, drawing or talking. The particular direct questions. The KFD refers

boundaries of confidentiality were made directly to the child’s own family and could,

clear, as were procedures that would be therefore, potentially inhibit expression for

followed in the event of ongoing harm being children who find their family situation

disclosed. Consent was checked again at the confusing or traumatic. However, when

beginning of each child’s session. The children are asked to draw as well as talk

impact of the session was continuously moni- about emotional experiences, they have

tored using a pictorial rating scale to help been found to report more than twice as

children express how they were feeling. much information than those who are asked

Frequent opportunities to stop the sessions just to talk (Gross & Harlene, 1998). Further-

were offered. Time was made at the end of more, as with play assessments, drawing

each session for further free play or drawing allows children to express non-declarative

and monitoring of each child’s emotional memories which may have been stored pre-

state. All of the families were linked into verbally or following trauma (Moore, 1994).

support services. Agreement was made to Each of the mothers completed a semi-

call on staff known to the families should this structured interview. Interview prompts

be necessary, although this was not in fact guided each mother to talk about her child,

needed. their relationship and the child’s character-

istic responses over time. Some interview

Data collection prompts also sought contextual information

In deciding the methods of data collection, about the family and the domestic violence

priority was given to supporting children to that had occurred. This information facili-

express their experiences in a way that was tated interpretation of the data from the

familiar and meaningful given their develop- children’s projective assessments.

mental stage and traumatic experiences.

Each child completed eight stories, selected Data analysis

from the Story Stem Assessment Profile Transcripts of the children’s stories, together

(SSAP). The SSAP was originally developed with the interview data from the mothers,

Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1 93

Victoria Thornton

were all analysed using grounded theory. which Dan had called the police, had taken

A brief summary interpretation of each of place the previous April. Similarly Gemma,

the children’s drawings was also produced, aged six, drew a tiny female figure with a

noting features that were highlighted in the break in the line drawn for her right arm.

literature as potentially significant (e.g. Gemma’s mother spoke during her interview

Malchiodi, 1997; Wohl & Kaufman, 1985). of an incident when her violent partner had

All interpretations were made cautiously, picked Gemma up and thrown her across the

with no single feature used as a sole indi- room, causing injury to her right arm.

cator of a child’s emotional experience and For all of the children, the content and

no fixed meanings applied to any images. style of their drawings and stories evidenced

These summaries were then used to further both emotional distress and negative expec-

elaborate and validate the themes found tations of family relationships. All of the

through the grounded theory analysis. mothers were felt by the researcher to be

Conceptual links were made between the impressively open in describing the domestic

themes, grouping them into categories and violence experienced within their family.

leading to an initial theoretical model, as However, the views offered by mothers about

shown in Figure 1. The model was shared the emotional impact of these experiences

with four of the participant mothers, all of on their children frequently underestimated

whom felt that it was a valid representation or missed aspects of the children’s difficul-

of their family’s experience. ties as represented in their play and art.

In attempting to explore and map this

Results emotional impact for the current study,

All of the children spent an hour with the precedence was given to the children’s data

researcher and willingly engaged in the play with information gathered from the mothers

and drawing tasks. Many of the children serving primarily to aid interpretation. The

asked to continue with further stories and model generated is illustrated in Figure 1.

drawings of their own choice and several of

the children asked whether they would be Qualities of domestic violence

able to meet with the researcher again. The Interview data from the mothers confirmed

way in which these children presented even that all of the children within this small-scale

within a single meeting, conveyed a sense of study had witnessed physical and verbal

their need to connect with someone who aggression directed at their mother, either

would listen to and contain their experi- from within the same room or overheard

ences. In the examples that follow, all names from another room in the house. During

have been changed to preserve anonymity. their play and drawing assessments, the

The validity of the play and drawing children frequently represented violence

assessments as a means to facilitate the and aggression, depicting it as powerful, as

children to share their experiences was causing pain and as being beyond control.

supported. Several of the children included When asked to draw a person, Aaron, age 7,

in their play and drawing, aspects of the chose to draw a wrestler, filling the entire

domestic violence that were separately and page (Figure 2). This powerful image is in

independently reported by their mothers. contrast to the tiny stick figures Aaron drew

For example, Dan, aged 8, told the story of a when he was asked to draw his family (Figure

boy, complaining that he gets, ‘a pain in my 3), as well as being at odds with the timid and

head, every April and nothing can sort it withdrawn presentation of Aaron himself,

out’. His mother separately reported within both within the research interview and

her interview that the worst incident of phys- reported by his mother.

ical violence from her ex-partner, during

94 Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1

Understanding the emotional impact of domestic violence on young children

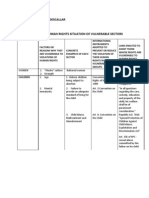

Figure 1: Theoretical model of the emotional impact of domestic violence on

young children.

Qualities of domestic violence

l Powerful

l Causes pain

l Beyond control

Impact on children’s feelings Impact on family dynamics

l Unhappiness l Care available for children

l Anxiety l Communication and

l Anger collaboration

l Confusion l Divided loyalties

l Routine and predictability

l Containment and security

Children’s coping responses

l Keeping adults close

l Acceptance and self-reliance

l Taking responsibility

Children’s capacity to

process emotions

Impact on children’s feelings Impact on family dynamics

Feelings ranging from unhappiness and As well as creating a range of distressing

anxiety to anger and confusion were evident emotions for young children, this study

in the children’s data. Many of the children’s found that domestic violence also has a

drawings included excessive heavy shading concurrent disrupting impact on relation-

in selective areas or figures, indicating feel- ships and dynamics within the whole family.

ings of anxiety (Koppitz, 1968). Five-year-old The children’s representations of family

Jane scribbled heavily over the arms, legs showed a number of perceived impacts of

and body of (only) the male figure in her domestic violence including; a disruption to

KFD. Jane’s older sister Jessica, aged 7, the care available for children; reducing

heavily coloured-in just the faces of all the opportunities for communication and

family members in her KFD, meaning that collaboration in decision making; forcing

she depicted all of her figures without eyes, divided loyalties; disrupting routines and

ears or mouths. As she drew she said, ‘I don’t predictability and; reducing parents’

want to put my eyes on’ thus allowing her to capacity to provide containment and security

disconnect from perceiving or feeling the for children.

traumatic experiences around her.

Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1 95

Victoria Thornton

Figure 2: Aaron’s Human Figure Drawing. Figure 3: Aaron’s Kinetic Family Drawing.

Children from all five families in the police arriving following an argument

study portrayed parents’ capacity to notice between two parents. Dan was keen to point

and attune to children’s distress as low. Nine- out that the son in the story had not tele-

year-old Andrew completed a story stem phoned the police and was not to blame for

about a child crying outside on his own with, them coming. Andrew (age 9) managed to

‘Lewis (a sibling) and daddy get up, cause avoid aligning himself with either parent by

they don’t hear the crying and they walk off’. omitting both his mother and his father

Gemma (age 6) goes further in her comple- from his KFD. After drawing himself and his

tion of the same story, to suggest that the two brothers Andrew told me, ‘I’m going to

limited care available to children is directly do two more people and that’s um, my

related to mothers investing this time in cousin Dean and then I’ll do… daddy or

their partners instead. This was a theme that mummy… That’s a bit unfair. Maybe, maybe

was repeatedly raised in many of the our uncle’.

mothers’ interviews. The crying child in Several children represented in their

Gemma’s story finds her own way home stories their sense that the containment

unnoticed. The child’s distress and her usually provided by parents, was missing.

arrival home are both ignored by her mother Parental figures were often depicted as

who ‘gets up and she (mum) goes to walk in lacking influence, as failing to provide

the kitchen. She gets a cup of tea, makes boundaries or as behaving in child-like ways.

some to dad and he drinks it all up’. Jane (age 5) depicted a very chaotic scene

Children’s confusion over which parent when completing a story stem about a child

to remain loyal to, was repeatedly played out spilling her drink. None of the adults in the

in their stories and drawings. Dan (age 8) story commented on the child’s behaviour or

alternately put the mother and then the found a practical solution to the spilled

father into jail when he told a story about the drink. Instead, all of the characters, both

96 Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1

Understanding the emotional impact of domestic violence on young children

children and adults, responded by repeat- Figureresulted

never 4: Mandy’s Human Figurethe

in overpowering Drawing.

never

edly throwing their own drinks and knocking

over furniture until the entire house fell

down around them.

Children’s coping responses

The range of impacts on family dynamics

both intensify the difficult and distressing

emotions experienced by children and

concurrently reduce the support available to

them to process their feelings. Children

represented in their play and drawing, a

number of strategies to manage and cope

with this reality. These include attempts to

keep adults close; acceptance of the never resulted in overpowering the aggressor

domestic violence and developing skills in in the stories. Many of the children also

self-reliance; and taking responsibility for demonstrated a very independent attitude to

the violence and for their mothers. problem solving in their stories, possibly

Many of the children depicted in their reflecting their expectation that adults would

stories and drawings children with huge not come to their aid. However, whilst these

smiles, who were endlessly forgiving or who approaches may serve children in the short-

worked hard to gain praise, making them- term, the long-term reality is that separating

selves as easy as possible to love. Whilst this themselves from the support of their care-

inclination to please in some cases led to givers is not an option. Not only do children

children being very hard-working in school, rely on their parents and want to keep them

in over half of the families mothers talked close, but many children also feel responsible

about their children asking to stay home for the safety of their mothers, which again,

from school or faking illness in efforts to stay draws them back into the family.

close to their mothers. Mandy (age 8) indi- All of the children portrayed in their

cated her strong desire to keep her mother story stem responses, children intervening

close to her by ending the majority of her and stopping arguments between adults.

stories with the mother and daughter charac- Dan (age 8) even created extra characters

ters spending time alone together and all of such as policemen and lifeguards in his

the other story characters disappearing. stories who waited near to the adults whilst

Mandy also, very unusually drew two figures children were away at school or in bed. Some

in her HFD, rather than a drawing of a single children also took the idea of responsibility

human figure as requested (see Figure 4). further to depict their perception that the

She told me that the figures were herself and children were to blame for arguments

her mother and she filled the rest of the happening in the first place. Seb (age 5)

page with numerous large clouds, suggesting continued this theme through several of his

anxiety, perhaps about her mother, or about stories, with ‘mummy’ and ‘daddy’ being

her own capacity to feel complete without angry with their son for causing arguments

her mother (Wohl & Kaufman, 1985). and difficulties.

All of the children represented violence

in their stories indicating their perception Children’s capacity to process emotions

that it was part of family life. Several of the The model suggests that while domestic

boys went further by portraying child charac- violence is ongoing, children experience

ters making weapons or forming alliances to repeated emotional distress and family

protect themselves, although these attempts dynamics continue to be disrupted, meaning

Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1 97

Victoria Thornton

that children are left with inadequate coping adolescents who have experienced domestic

strategies and ultimately therefore become violence. This finding further refutes any

overwhelmed. For some children, their lingering suggestions that children do not

internal chaos was represented vividly in the notice or remember domestic violence

style of their story-telling and drawing. taking place in their homes. A key theme

Others had managed to distance themselves from this study was that living with domestic

from their overwhelming feelings, but their violence is emotionally overwhelming for

underlying anxieties were evident in their young children. How this emotional experi-

drawings and play. All of the mothers ence can be recognised and alleviated by

reported changes in their children’s presen- professionals is of key importance. Early

tation since they had separated from their quantitative studies highlighted physical

violent partners, with children becoming problems such as bedwetting and failure to

more expressive in their emotions. The thrive as being prevalent amongst younger

increased feelings of stability and security children who have experienced domestic

within the family overall were cited by several violence. It seems likely that these ostensibly

mothers as creating the window of possibility physical presentations are the route through

for this change. However, many of the which emotional turmoil shows itself in

mothers acknowledged still feeling over- children who lack the words to voice it or

whelmed themselves at times. It is to be who feel compelled to keep the domestic

expected, therefore, that children’s own violence they are experiencing a secret. Simi-

journeys towards emotional security were larly, a child’s behavioural presentation can

still far from complete. provide a useful indicator of their under-

lying emotional distress, although emotions

Discussion and evaluation such as anxiety or unhappiness may be

The data for the present study was drawn displayed through very different behaviours

from a small, non-representative sample of depending on the age, gender and person-

children. Further exploration is necessary to ality of the child. Play and art offer a further

validate the theoretical model and to extend window into the internal emotional world of

its utility. The model as it stands has limited a young child, with the potential to signal to

capacity to explain individual differences in professionals that a child is struggling with

children’s responses to domestic violence, emotional experiences that they are unable

with the only mediating factor suggested to name or process alone.

being family dynamics. Further research

using a larger sample size could also explore Implications for clinical and

the impact of other variables, including educational professionals

gender and age, on emotional responses to The current study has shown that even a

domestic violence. Despite these points for non-clinical sample of children evidence a

development, the findings of the present negative emotional impact following

study make an interesting contribution to domestic violence. However, younger

our understanding of the emotional impact children’s relative lack of cognitive and

of domestic violence on younger children. In linguistic skills together with the secrecy and

addition, the methodology and the wealth of isolation that often accompanies domestic

information gathered through it, clearly violence means that child victims of

show that young children can and should be domestic violence are very unlikely to spon-

valued and enabled to participate in taneously talk about their experiences. It

research. therefore remains for professionals to be

Overall the themes found here resonate aware of important indicators of emotional

with many of those reported in previous distress in children’s presentation and

qualitative research with older children and behaviour. Educational professionals are well

98 Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1

Understanding the emotional impact of domestic violence on young children

placed to notice these signs given their strategy being introduced in schools to help

extended contact with children and their all children manage their stress and anxiety

ability to repeatedly observe young levels is the inclusion of mindfulness prac-

children’s behaviour, play and art work. tices within the school day. Mindfulness can

Training and consultation to schools be of use to all children, with particular

regarding the prevalence of domestic benefits possible for those who are strug-

violence and signs to look out for in children gling with high levels of emotional distress.

would increase the skills set and confidence Some children will require more inten-

of staff to effectively notice and support sive support following domestic violence in

these children, and refer on to clinical the form of individual or group therapy from

services for those most in need. clinical services. Where appropriate, thera-

The model generated suggests that peutic support could also be offered for

young children become overwhelmed family groups and mother-child dyads.

following domestic violence due to a combi- Boosting the resilience of the family unit and

nation of direct trauma combined with indi- the relationships between children and their

rect influences on the family support system, mothers is a key part of the healing process.

which together leave the child with inade- Family members can be supported to

quate coping strategies to effectively process acknowledge and shift away from the nega-

their emotions. This process is in line with tive changes that domestic violence has

descriptions of ‘complex developmental inflicted on family dynamics, as well as

trauma’ which refers to a collection of symp- bringing the role of emotional containment

toms resulting from ongoing unmanageable and connection back within the parent-child

stress during childhood. Van der Kolk writes relationship.

that, without the availability of a caregiver to However help is offered, we need to start

modulate the child’s arousal levels, the child by listening to the communications of young

is left ‘unable to organise and categorise its children who have lived with domestic

experiences in a coherent fashion’. When violence, about their emotional worlds. They

these traumatised children present in school are able to show us, using their own

perhaps with high levels of emotional methods, if we can tune in and listen.

arousal or conversely with extreme anxious

withdrawal, their primary need is for an Address for correspondence

attuned adult to notice, understand and co- Dr Victoria Thornton

regulate their emotional distress. If schools CAMHS, Seaside View,

can take this approach there will be benefits Brighton General Hospital,

both for children’s emotional well-being and Elm Grove,

for their behaviour and capacity to learn in Brighton, BN2 3EW.

school. An increasingly popular pro-active Email: victoria.thornton@nhs.net

Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1 99

Victoria Thornton

References

Abrahams, C. (1994). Hidden victims: Children and Kitzmann, K.M., Gaylord, N.K., Holt, A.R. & Kenny,

domestic violence. London: NCH Action for E.D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic

Children. violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of

Burns, R.C. & Kaufman, S.H. (1972). Action, styles and Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339–352.

symbols in kinetic family drawings: An interpretive Koppitz, E.M. (1968). Psychological evaluation of

manual. New York: Brunner/Mazel. children’s human figure drawings. New York: Grune

Chaplin, R., Flatley, J. & Smith, K. (2011). Crime in & Stratton.

England and Wales 2010/2011. London: Home McGee, C. (2000). Childhood experiences of domestic

Office. violence. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Co-ordinated Action Against Domestic Abuse, Malchiodi, C.A. (1998). Understanding children’s

(CAADA) (2013). Bristol, UK. drawings. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Council of Europe (2002). Recommendation of the Martin, S.G. (2002). Children exposed to domestic

Committee of Ministers to Member States on the violence: Psychological considerations for health

Protection of Women Against Violence. Strasbourg: care practitioners. Holistic Nursing Practice, 16(3),

Council of Europe. 7–15.

Epstein, C. & Keep, G. (1995). What children Moore, M.S. (1994). Reflections of Self: The use of

tell Childline about domestic violence. drawing in evaluating and treating physically

In A. Saunders, C. Epstein, G. Keep & ill children. In A. Erskine & D. Judd (Eds.),

T. Debbonaire (Eds.), It hurts me too: Children’s The imaginative body: Psychodynamic therapy in

experiences of domestic violence and refuge life. health care. London: Whurr.

Bristol: WAFE/Childline/NISW. Mullender, A., Hague, G., Imam, U., Kelly, L., Malos,

Ericksen, J.R. & Henderson, A.D. (1992). Witnessing E. & Regan, L. (2002). Children’s perspectives on

family violence: The children’s perspective. domestic violence. London: Sage.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17, 1200–1209. NSPCC (2011). Child abuse and neglect in the UK today.

Goddard, C. & Bedi, G. (2010). Intimate partner London: NSPCC.

violence and child abuse: A child-centred Office for National Statistics (2013). Focus on violent

perspective. Child Abuse Review, 19, 5–20. crime and sexual offences, 2011/2012. Newport:

Goldblatt, H. (2003). Strategies of coping among Office for National Statistics.

adolescents experiencing inter-parental violence. Shamir, H., Du Rocher Schudlich, T. & Cummings,

Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 532–552. E.M. (2001). Marital conflict, parenting styles

Gross, J. & Harlene, H. (1998). Drawing facilitates and children’s representations of family relation-

children’s verbal reports of emotionally laden ships. Parenting, Science and Practice, 1(1),

events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 123–151.

4(2), 163–179. Snyder, G.R. (1998). Men’s violence during

Grych, J.H., Wachsmuth-Schlaefer, T. & Klockow, L. parenthood-related transitions in the couple

L. (2002). Interpersonal aggression and young relationship: Partner abuse during pregnancy

children’s representations of family relation- and/or children’s infancy. Dissertations Abstracts

ships. Journal of Family Therapy, 16(3), 259–272. International: Section B: The Sciences and

Hodges, J., Hillman, S. & Steele, M. (2004). Story stem Engineering, 59 (5–B), 2437.

assessment profile coding manual. London: Van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma

The Anna Freud Centre. disorder: Towards a rational diagnosis for

Huetteman, M.J. (2005). Investigation of internal chronically traumatised children. Psychiatric

representations of pre-schoolers who witness Annals.

domestic violence. Dissertation Abstracts Wohl, A. & Kaufman, B. (1985). Silent screams and

International: Section B. The Sciences and hidden cries: An interpretation of artwork by children

Engineering, 65/8–B, 4289. from violent homes. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

100 Educational & Child Psychology Vol. 31 No. 1

Copyright of Educational & Child Psychology is the property of British Psychological Society

and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without

the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or

email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Tony Blauer Panic Self DefenseDocument11 pagesTony Blauer Panic Self Defensecepol100% (1)

- Therapy Does Not Include SexDocument26 pagesTherapy Does Not Include SexCori StaymakingMoneyNo ratings yet

- If it happens to your child, it happens to you!: A Parent's Help-source on Sexual AssauFrom EverandIf it happens to your child, it happens to you!: A Parent's Help-source on Sexual AssauNo ratings yet

- Research Project On Domestic Violence (Autosaved) 2Document7 pagesResearch Project On Domestic Violence (Autosaved) 2Elvis MangisiNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No 8049Document2 pagesRepublic Act No 8049Victoria AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court On StridhanDocument25 pagesSupreme Court On StridhanLatest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Neurodevel Impact PerryDocument20 pagesNeurodevel Impact Perryluz tango100% (1)

- The Issue of Child Abuse and Neglect Among StudentsDocument11 pagesThe Issue of Child Abuse and Neglect Among StudentsLudwig DieterNo ratings yet

- Final Case Study On The Movie Precious: Student's Name Institution Course Name Instructor's Name DateDocument8 pagesFinal Case Study On The Movie Precious: Student's Name Institution Course Name Instructor's Name Datetopnerd writerNo ratings yet

- Abolition of Slavery in EthiopiaDocument4 pagesAbolition of Slavery in Ethiopiaseeallconcern100% (1)

- The Effects of Domestic Violence On Academic Performance of Children Upto 16 Years in KenyaDocument19 pagesThe Effects of Domestic Violence On Academic Performance of Children Upto 16 Years in KenyaJablack Angola Mugabe100% (9)

- How To Read Childrens Drawings FinalDocument184 pagesHow To Read Childrens Drawings FinalLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- Project Work On GenocideDocument16 pagesProject Work On Genocideashu pathakNo ratings yet

- Pathways To Poly-VictimizationDocument14 pagesPathways To Poly-VictimizationpelosirosnanetNo ratings yet

- Defining Child Sexual AbuseDocument14 pagesDefining Child Sexual AbuseAndreas Springfield GleasonNo ratings yet

- The Role of Family and Peer Relations in Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour: Comparison of Four Ethnic GroupsDocument18 pagesThe Role of Family and Peer Relations in Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour: Comparison of Four Ethnic GroupsSunnyNo ratings yet

- Stopping Family Violence: Integrated Approaches To Violence Against Women and Children (2018)Document12 pagesStopping Family Violence: Integrated Approaches To Violence Against Women and Children (2018)Children's InstituteNo ratings yet

- Body Modifications FrankDocument17 pagesBody Modifications FrankSimion FloryNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature This Chapter We Will Present The Related Topics in Our Study. The Topics Here WillDocument5 pagesReview of Related Literature This Chapter We Will Present The Related Topics in Our Study. The Topics Here WillJohnLloyd O. Aviles100% (1)

- The Association Between Bullying Behaviour, Arousal Levels and Behaviour ProblemsDocument15 pagesThe Association Between Bullying Behaviour, Arousal Levels and Behaviour ProblemsHepicentar NišaNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Victim BlamingDocument21 pagesWeek 5 Victim BlamingDavid100% (1)

- What Is Victim BlamingDocument13 pagesWhat Is Victim BlamingTabaosares JeffreNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory and Child AbuseDocument7 pagesAttachment Theory and Child AbuseAlan Challoner100% (3)

- Legal Opinion - Legal Research BarcenaDocument3 pagesLegal Opinion - Legal Research BarcenaKen BarcenaNo ratings yet

- Chandrashekar HM Disseration ProposalDocument7 pagesChandrashekar HM Disseration Proposalbharath acharyNo ratings yet

- Hut H Bocks 2001Document22 pagesHut H Bocks 2001Mario SilvaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Domestic Violence To Children: A Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesEffects of Domestic Violence To Children: A Literature ReviewJoefritzVaronNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Child Abuse and Exposure To DomesticDocument11 pagesThe Effects of Child Abuse and Exposure To Domesticvalentina chistrugaNo ratings yet

- Articole Stiintifice PsihologieDocument11 pagesArticole Stiintifice PsihologieMircea RaduNo ratings yet

- Individual Measurement of Exposure To Everyday Violence Among Elementary Schoolchildren Across Various SettingsDocument24 pagesIndividual Measurement of Exposure To Everyday Violence Among Elementary Schoolchildren Across Various SettingsAdriana VeronicaNo ratings yet

- How Domestic Violence Impact On Children Behaviour in United States Chew Ji Cheng Language and Knowledge Miss Shivani 3 of December, 2014Document11 pagesHow Domestic Violence Impact On Children Behaviour in United States Chew Ji Cheng Language and Knowledge Miss Shivani 3 of December, 2014Anne S. YenNo ratings yet

- Polivitimização e Exposição À Violência Juvenil em Vários ContextosDocument7 pagesPolivitimização e Exposição À Violência Juvenil em Vários ContextosRegina CordeiroNo ratings yet

- Child Witnesses To Domestic Violence: A Meta-Analytic ReviewDocument14 pagesChild Witnesses To Domestic Violence: A Meta-Analytic ReviewMarch ElleneNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse Final DraftDocument10 pagesChild Abuse Final Draftapi-272816863No ratings yet

- Assessing Resilience in PreschDocument16 pagesAssessing Resilience in Preschdaniela CeballosNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleDocument10 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: Research ArticleAlexandraNo ratings yet

- Lyons Ruth1986Document22 pagesLyons Ruth1986ana raquelNo ratings yet

- Fisayomi PROJECT 4Document67 pagesFisayomi PROJECT 4AKPUNNE ELIZABETH NKECHINo ratings yet

- Articole Stiintifice PsihologieDocument10 pagesArticole Stiintifice PsihologieMircea RaduNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0145213418301881-Main Intimate Partner ViolenceDocument9 pages1-S2.0-S0145213418301881-Main Intimate Partner ViolenceVissente TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Abuse Among Children in Conflict With The Law in Bahay Pag-AsaDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Abuse Among Children in Conflict With The Law in Bahay Pag-AsaMarlone Clint CamilonNo ratings yet

- Ege Land 2009Document5 pagesEge Land 2009RavennaNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 - Siblings ViolenceDocument9 pagesAssignment 2 - Siblings Violencewafin wardahNo ratings yet

- Factors Discriminating Among Profiles of Resilience and Psychopathology in Children Exposed To Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)Document13 pagesFactors Discriminating Among Profiles of Resilience and Psychopathology in Children Exposed To Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)Eszter LNo ratings yet

- Is Low Empathy Related To Bullying After Controlling For Individual and Social Background VariablesDocument13 pagesIs Low Empathy Related To Bullying After Controlling For Individual and Social Background VariablesElena OpreaNo ratings yet

- Cappadocia, Weiss & Pepler (2012) - AUTISMDocument35 pagesCappadocia, Weiss & Pepler (2012) - AUTISMdeea luciaNo ratings yet

- Mother's Perspectives On Signs of Child Sexual Abuse in Their Families - Gilgun, J. & Anderson, G.Document10 pagesMother's Perspectives On Signs of Child Sexual Abuse in Their Families - Gilgun, J. & Anderson, G.martiinrvNo ratings yet

- Project On Uk Unborn KidsDocument16 pagesProject On Uk Unborn Kidsjosephmainam9No ratings yet

- Mother-Child Emotion Dialogues in Families Exposed To Interparental ViolenceDocument22 pagesMother-Child Emotion Dialogues in Families Exposed To Interparental ViolenceLucelle NaturalNo ratings yet

- PERCEPTION-OF-TEENAGERS-WHO-HAVE-WITNESSED-THEIR-PARENTS-AS-A-VICTIM-OF-DOMESTIC-VIOLENCE[2]Document13 pagesPERCEPTION-OF-TEENAGERS-WHO-HAVE-WITNESSED-THEIR-PARENTS-AS-A-VICTIM-OF-DOMESTIC-VIOLENCE[2]Christian CudadaNo ratings yet

- (2011) Parenting and Social Anxiety Fathers' Vs Mothers' Influence On Their Children's Anxiety in Ambiguous Social SituationsDocument8 pages(2011) Parenting and Social Anxiety Fathers' Vs Mothers' Influence On Their Children's Anxiety in Ambiguous Social SituationsPang Wei ShenNo ratings yet

- Putnam 2006Document11 pagesPutnam 2006NilamNo ratings yet

- Bullying Defiance TheoryDocument25 pagesBullying Defiance TheoryLeogen TomultoNo ratings yet

- Assignment # KR 21-19Document6 pagesAssignment # KR 21-19Nathan RonoNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: Dalhee Yoon, Stacey L. Shipe, Jiho Park, Miyoung YoonDocument9 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: Dalhee Yoon, Stacey L. Shipe, Jiho Park, Miyoung YoonPriss SaezNo ratings yet

- Aversive Exchanges With Peers and Adjustment During Early Adolescence: Is Disclosure Helpful?Document17 pagesAversive Exchanges With Peers and Adjustment During Early Adolescence: Is Disclosure Helpful?Christine BlossomNo ratings yet

- Intergenerational Transmission of Violence: What-When-HowDocument1 pageIntergenerational Transmission of Violence: What-When-HowAcheropita PapazoneNo ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution TacticsDocument16 pagesConflict Resolution TacticsMarlena AndreiNo ratings yet

- Agresiveness in ChildrenDocument13 pagesAgresiveness in ChildrenPsihoterapeut Alina VranăuNo ratings yet

- 5461 Article 65087 1 10 20211223Document20 pages5461 Article 65087 1 10 20211223謝華寧No ratings yet

- La Concurrencia de FactoresDocument22 pagesLa Concurrencia de FactoresAngel Wxmal Perez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Correlation Between Child Abuse and Future Violent BehaviourDocument6 pagesCorrelation Between Child Abuse and Future Violent BehaviourNathan RonoNo ratings yet

- Is A History of School Bullying Civtimization Associated Whit Adult Suicidal IdeationDocument6 pagesIs A History of School Bullying Civtimization Associated Whit Adult Suicidal IdeationFerx Fernando PachecoNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument97 pagesProjectnakaka943No ratings yet

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument32 pagesConceptual FrameworkVlynNo ratings yet

- A Family Affair Examining The Impact of Parental IDocument13 pagesA Family Affair Examining The Impact of Parental ILawrenceNo ratings yet

- AggressionDocument9 pagesAggressionapi-645961517No ratings yet

- Violencia en La Pareja1 PDFDocument13 pagesViolencia en La Pareja1 PDFNata ParraNo ratings yet

- Child MaltreatmentDocument17 pagesChild MaltreatmentFabian Mauricio CastroNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Polyvictimization, Emotion Dysregulation, and Social Support Among Emerging Adults Victimized During ChildhoodDocument18 pagesThe Relationship Between Polyvictimization, Emotion Dysregulation, and Social Support Among Emerging Adults Victimized During ChildhoodKhoyrunnisaa AnnabiilahNo ratings yet

- FINAL Research ProposalDocument14 pagesFINAL Research ProposalPalvisha FarooqNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of School Bullying in Hungarian Primary and High SchoolsFrom EverandPrevalence of School Bullying in Hungarian Primary and High SchoolsNo ratings yet

- Draw Me Everything That Happened To You Exploring Childrens DrawingsDocument6 pagesDraw Me Everything That Happened To You Exploring Childrens DrawingsLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- Emotional Indicatores in Children Human Figure PDFDocument275 pagesEmotional Indicatores in Children Human Figure PDFLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- What Vygotsky Can Teach Us AboutDocument13 pagesWhat Vygotsky Can Teach Us AboutLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- Art, Meaning, and Perception: A Question of Methods For A Cognitive Neuroscience of ArtDocument18 pagesArt, Meaning, and Perception: A Question of Methods For A Cognitive Neuroscience of ArtLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- The Physical Characteristics of Line: MeasureDocument12 pagesThe Physical Characteristics of Line: MeasureLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Vincent Van GoghDocument21 pagesAnalysis of Vincent Van GoghLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- 6desenhoinfantil USPDocument13 pages6desenhoinfantil USPLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant: First DivisionDocument9 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant: First DivisionChoi ChoiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Foster Care On Development: Development and Psychopathology February 2006Document21 pagesThe Impact of Foster Care On Development: Development and Psychopathology February 2006Salvador Richmae LacandaloNo ratings yet

- PAD370 Budget ProposalDocument55 pagesPAD370 Budget ProposalAlia NdhirhNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Chap 6-9Document14 pagesHuman Rights Chap 6-9Lucky VastardNo ratings yet

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 05/30/15Document9 pagesPeoria County Booking Sheet 05/30/15Journal Star police documentsNo ratings yet

- Developing Healthy RelationshipsDocument10 pagesDeveloping Healthy Relationshipsapi-638515435No ratings yet

- Diversity and Equal Opportunities-1Document7 pagesDiversity and Equal Opportunities-1symhoutNo ratings yet

- Cyber CrimeDocument2 pagesCyber Crimericha928No ratings yet

- Bullying in Schools Bullying in SchoolsDocument8 pagesBullying in Schools Bullying in SchoolsMihaela CosmaNo ratings yet

- Zero Dropout FinalDocument24 pagesZero Dropout FinalPrincess Kylah Chua TorresNo ratings yet

- By Dr. Becky A. Bailey: Building Resilient ClassroomsDocument22 pagesBy Dr. Becky A. Bailey: Building Resilient ClassroomsBillStNo ratings yet

- Duvvury Et Al. 2013 Intimate Partner Violence. Economic Costs and ImplicatiDocument97 pagesDuvvury Et Al. 2013 Intimate Partner Violence. Economic Costs and Implicatisamson jinaduNo ratings yet

- Defamation NotesDocument3 pagesDefamation NotesHelen HeNo ratings yet

- PDF Torture in Healthcare Publication PDFDocument346 pagesPDF Torture in Healthcare Publication PDFsanjnuNo ratings yet

- Law Relating To Domestic Violence, Vijendra Kumar A Gogia & Company Hyderabad 2007Document4 pagesLaw Relating To Domestic Violence, Vijendra Kumar A Gogia & Company Hyderabad 2007ashoknalsarNo ratings yet

- Prop 57 - Nonviolent CrimesDocument6 pagesProp 57 - Nonviolent CrimesLakeCoNewsNo ratings yet

- Table of CasesDocument6 pagesTable of CasesJoshua ParilNo ratings yet

- Conclusions-VOL4-12-The (Irish Government) Commission To Inquire Into Child AbuseDocument10 pagesConclusions-VOL4-12-The (Irish Government) Commission To Inquire Into Child AbuseJames DwyerNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Abuse Safeguarding of Vulnerable AdultsDocument51 pagesPrevention of Abuse Safeguarding of Vulnerable Adultscristian38_tgv-1No ratings yet

![PERCEPTION-OF-TEENAGERS-WHO-HAVE-WITNESSED-THEIR-PARENTS-AS-A-VICTIM-OF-DOMESTIC-VIOLENCE[2]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/730674957/149x198/cd66d91213/1715205612?v=1)