Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Same Old Principles in The New Manufacturing

Uploaded by

Andrey MatusevichOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Same Old Principles in The New Manufacturing

Uploaded by

Andrey MatusevichCopyright:

Available Formats

National Competitiveness

The

New Same Old

ManufacturingPrinciples in the

by David A. Hounshell

From the Magazine (November 1988)

Dynamic Manufacturing: Creating the Learning Organization,

Robert H. Hayes, Steven C. Wheelwright, and Kim B. Clark (New

York: Free Press, 1988) 429 pages, $24.95.

American Business: A Two-Minute Warning, C. Jackson Grayson,

Jr. and Carla O’Dell (New York: Free Press, 1988) 368 pages, $24.95.

In the fall of 1911, Frederick Winslow Taylor rushed into print his

Principles of Scientific Management, a thin book that had been

gestating since the early 1890s. Taylor was notable in mechanical

engineering circles for his codiscovery in 1899 of high-speed steel

and for his brilliant paper in 1906, “The Art of Cutting Metals,”

which reported on over 30,000 experiments he had conducted at

the Midvale Steel Company during the 1880s. By applying

scientific techniques—like varying the speed and feed of cutting

tools or varying their shapes—he had found the “one best way” to

do any metal-cutting task. On the basis of these experiments, he

believed he could optimize the performance of the entire machine

shop, including the performance of its workers.

With evangelical fervor, Taylor vowed to root out all “systematic

soldiering” (i.e., workers doing less than an “honest day’s work”).

Doing so, he insisted, required a complete mental revolution in

U.S. industry. Taylor tried consulting and worked hard to

convince several manufacturing executives to yield control of

their production operations to him and his associates. As

managers had eclipsed owners, he taught, efficiency experts

would eclipse managers.

Taylor advocated pushing responsibility onto people who, like

him, had studied the dynamics of production. In return he

promised not only productivity increases but also peace between

capital and labor.

Unfortunately, Taylor had little initial success; in more than one

instance, he and his associates were fired by companies that had

retained their services. His reputation as a production expert

would probably have remained obscure had it not been for the

attorney and future Supreme Court justice, Louis Brandeis, who

had been hired in 1910 by an association of companies opposed to

proposed rate hikes by the eastern railroads. Brandeis latched

onto Taylor’s theoretical work, labeled it “scientific

management,” and put one of Taylor’s disciples on the witness

stand to tell the Interstate Commerce Commission how the

railroads could save a million dollars a day. Headlines throughout

the United States proclaimed Taylor’s gospel. An efficiency craze

ensued; factories, schools, homes, and even churches were soon

Taylorized—hence Principles of Scientific Management.

Taylor’s new book used parables to get his teachings across. His

favorite was the story of “Schmidt,” a stocky Pennsylvania

German who was a pig-iron loader at Bethlehem Steel. Schmidt

loaded about 12 tons of the 92-pound iron pigs each day (and then

ran home to work on his little dream house). Using Taylor’s

principles, “scientific managers” raised Schmidt’s output to 48

tons per day, and raised his daily wages from $1.15 to $1.85.

Schmidt achieved this remarkable gain, Taylor continued, not

only because of science but by being “a high-priced man.” “A

high-priced man,” Taylor recounted telling Schmidt, “does just

what he’s told to do and no back talk.” Taylor then put things on

the line with Schmidt: “When this man [i.e., the manager] tells

you to walk, you walk; when he tells you to sit down, you sit

down… Now you come here tomorrow morning and I’ll know

before night whether you are really a high-priced man or not.”

This was “rather rough talk,” Taylor conceded, but with a man of

“the mentally sluggish type as Schmidt,” it was “appropriate and

not unkind.”

Fifteen years later, in 1926, Henry Ford published an article, “Mass

Production,” in the thirteenth edition of the Encyclopedia

Britannica. In it he described revolutionary developments at the

Ford Motor Company—the highly specialized machinery, the

assembly line, and the $5 day. Interestingly enough, Ford alluded

to Taylor’s Schmidt to make clear how his approach differed from

Taylorism. Why, Ford asked, should pig iron be loaded by hand?

Why not do it with machinery or, better yet, why not eliminate the

need for pig iron by casting iron straight from the blast furnace?

In retrospect, however, Ford had actually hit on many of Taylor’s

assumptions about work without acknowledging the symmetries.

Taylor had not really envisioned Ford’s mechanized work

processes. He sought revisions in labor regimens without looking

for innovations in production hardware—while Ford and his

engineers had mechanized work processes and found workers to

feed and tend their machines.

And yet Ford had—perhaps inadvertently—applied Taylorist

ideas, such as time-and-motion studies, to lay out machining and

assembly processes. At Ford, ultimately, the special-purpose

machines and the assembly lines set the pace of work. Taylor was

known for his studied disregard for the worker. Ford, for his part,

was devoted to the hierarchical production organization

demanded by the machines, or to the elimination through

automation of skilled jobs on the line.

Taylor and Ford came to mind as I was reading Dynamic

Manufacturing, by Robert H. Hayes, Steven C. Wheelwright, and

Kim B. Clark of the Harvard Business School, and American

Business: A Two-Minute Warning, by C. Jackson Grayson, Jr. and

Carla O’Dell of the American Productivity and Quality Center.

Since Ford’s assembly-line revolution in 1913, the books justly

imply, companies in the United States—indeed, companies

throughout most of the world until quite recently—have pursued

manufacturing along Taylorist (and Fordist) lines. They have

defined jobs and work processes with great precision and saw

business organizations as hierarchies, out of a continuing belief

that workers “systematically soldier.” They’ve shared, at least in

part, Taylor’s manifest contempt for the worker.

Rather than seeing workers as assets to be nurtured and

developed, manufacturing companies have often viewed them as

objects to be manipulated or as burdens to be borne. And the

science of manufacturing has taken its toll. Where workers were

not deskilled through extreme divisions of labor, they were often

displaced by machinery. For many companies, the ideal factory

has been—and continues to be—a totally automated, workerless

facility.

Now in the wake of the eroding competitive position of U.S.

manufacturing companies, is it time for an end to Taylor’s

management tradition? The books answer in the affirmative,

calling for the institution of a less mechanistic, less authoritarian,

less functionally divided approach to manufacturing. Dynamic

Manufacturing focuses explicitly on repudiating Taylorism,

which it takes to be a system of “command and control.”

American Business: A Two-Minute Warning is written in a more

popular vein, but characterizes U.S. manufacturing methods and

the underlying mind-set of manufacturing managers in

unmistakably similar ways. Taylorism is the villain and the

anachronism.

Predictably, both books arrive at their diagnoses and prescriptions

through their respective evaluations of the “Japanese miracle.”

Whereas U.S. manufacturing is rigid and hierarchical, Japanese

manufacturing is flexible, agile, organic, and holistic. In the new

competitive environment—which favors the company that can

continually generate new, high-quality products—the Japanese

are more responsive. They will continue to dominate until U.S.

manufacturers develop manufacturing units that are, in Hayes,

Wheelwright, and Clark’s words, “dynamic learning

organizations.” Their book is intended as a primer.

“In contrast to the assumptions of Taylorism,” they argue, “world-

class manufacturing organizations do not divide people into those

who think and those who act. Learning and applying knowledge

must be high on everyone’s agenda, at every level in the

organization.”

Grayson and O’Dell’s book is also aimed at corporate managers

who are chasing the past, but it goes beyond Dynamic

Manufacturing in calling for sweeping reforms in the institutions

of American capitalism, from public policy to the educational

system.

To be sure, Grayson (the onetime price-control czar in the Nixon

administration) and O’Dell swear off state intervention in the

economy. They argue for no further protection in international

trade, and they oppose the establishment of an “industrial policy”

by the federal government—even though Japan has built its

current economic strength on the basis of what must rightfully be

called an industrial policy. They oppose currency devaluation as a

competitiveness strategy because it results in direct foreign

investment and the selling off of national assets. They warn that

government should not overemphasize capital investment or

invest more funds for research and development.

They do, however, call for a redistribution of R&D spending away

from defense. More strikingly, they put forth an eight-point

government program for victory in the competitiveness war. They

are very specific about how to achieve better education: much

higher pay for teachers, longer school days, a greatly expanded

school year, and larger average class sizes—which is, perhaps, a

too slavish desire to emulate the Japanese educational system.

The authors’ agenda also includes greater privatization of

government services, the reform of U.S. antitrust laws, and

improvement of commercial and industrial statistics-gathering to

reflect the shift in the economy toward services. They call for

raising productivity in government and for cutting the federal

budget deficit.

The fundamental weakness of the U.S. economy, they believe, is

related to the federal deficit but goes well beyond it. The problem

lies in the low savings rate. In fact, A Two-Minute Warning seems

to be as much meant for credit-card-wielding U.S. consumers as

for U.S. businesspeople.

If the parallels between these two books are striking, so are the

differences. Each draws heavily from industrial history to ground

its own analysis of America’s productivity problems. But the

books do not see quite the same history. Hayes, Wheelwright, and

Clark include a chapter called “America’s Manufacturing

Heritage” that reflects their vision of the golden age of

manufacturing in the United States, circa 1950. Their homily—it

really isn’t a history—tells us that the United States became a

manufacturing giant when it combined old-world skills, which

valued quality, with modern scientific knowledge, which valued

new ideas and efficiency—and kept this combination carefully in

balance.

Then three related things happened; those familiar with Professor

Hayes’s work will appreciate the drift of the argument. First, the

financial guys took charge and traded long-term growth for short-

term profits. Rates of productivity growth fell off. At the same

time, U.S. corporate complacency in world markets choked the

basic-research binge indulged in by technologically oriented

corporations after World War II. The management of industrial

R&D laboratories passed from those who had emphasized steady

improvement of products and processes to those who valued big

science and bet on great leaps forward—while military hardware

became the main objectives of R&D spending.

Finally, and perhaps most important, managers allowed Taylor’s

principles of scientific management and Ford’s notions about

hard automation to get out of hand. It was now that

manufacturing organizations became rigidly hierarchical and

authoritarian—anything but “learning” organizations. The

results, the three authors maintain, have been disastrous.

Grayson and O’Dell construct their history to sound the alarm,

not to harken back to the good old days. The United States is

following in the footsteps of Great Britain, they write, which did

not respond to turn-of-the-century warnings about America’s—

and Germany’s—rapidly rising economic power. As a

consequence, Great Britain—once the workshop of the world—

became a second-rate manufacturing nation, losing both

economic and political power in the process. Again, it is our

management tradition that is the real culprit.

Curiously, both historical arguments, illuminating as they are,

oversimplify U.S. industrial achievements because they

underestimate Taylor, overestimate pre-Taylor U.S. managers, or

both. Is it true, for example, that the British were warned of

impending economic demise just as contemporary U.S.

businesses have been warned? Yes and no.

In the 1850s, John Anderson and other British military officers

successfully pressed Parliament to fund an American-style small-

firearms manufacturing plant, which opened at Enfield in 1857.

The Enfield Armory was stocked with American-made machine

tools and managed by U.S. manufacturing experts. It turned out a

standardized rifle containing uniformly produced parts, a gun far

different from the handmade rifles and muskets produced by the

arms makers of Birmingham.

After the Enfield Armory opened, Anderson hoped it would

become a model for British manufacturers of all kinds of

consumer durables. He counseled that if his fellow citizens were

“wise in their generation,” they would “not despise this system of

manufacture but, on the contrary, will adopt it, for it will secure

for them a high vantage ground in competing with other parts of

the world.” If the British did not adopt American methods,

Anderson warned, “it is to be feared that American manufacturers

will before long become exporters…to England.” And yet the

British did not adopt U.S. manufacturing methods for another 50

years.

Why the slowness of the British response? British manufacturers

viewed most U.S. goods coming in before 1900 as being of poorer

quality than British products. Not only were U.S. goods all the

same but also they were made with lesser quality materials, were

poorly fitted together, and were not finished as perfectly as their

British counterparts. British consumers, the manufacturers

believed, expected less standardized, higher quality goods.

Actually, a small number of advanced U.S. companies, such as the

Singer Manufacturing Company, established factories in Britain

during the late nineteenth century using the same production

techniques as their sister factories in the United States. They did

well in the British and European markets; in fact, Singer’s British

factory produced goods at much lower cost than the United States

did. (Analogies to Japanese auto companies operating in the

United States are unavoidable.)

And so the American system of manufactures, as practiced at

companies like Singer, attained its ultimate logic in Taylorism

and Fordism. It is true, as Hayes, Wheelwright, and Clark recall,

that pre-Taylor America was a place of greater skill among

production workers. But the genius of American manufacturing

back then was really put to the production of goods that were

“good enough.” Our system of manufactures was built on the idea

of controlling for defects rather than pursuing—as an artist or

skilled craftsperson might—perfection. Nineteenth and early

twentieth century manufacturers in the United States understood

perfectly well that the quality of their goods was determined by

how far it deviated from an ideal form at a given price.

By 1900, the British could not touch the quality of U.S. goods—at

least not at the U.S. price—and, correspondingly, British

consumers began to make compromises. It is with standardized

production that U.S. goods conquered world markets. Eventually,

as Dynamic Manufacturing bemoans, extreme forms of

Taylorism, which made American workers feel that their products

were alien to them, led to a palpable decline in the quality of U.S.

products.

Hayes, Wheelwright, and Clark argue much more strongly the

immediate and practical claim that the United States has recently

lost its leadership in three bases of competition: relative cost,

relative quality, and relative innovativeness. This is where

Dynamic Manufacturing takes hold of the imagination.

Although many will contend that an overvalued dollar has played

an important role in the rapid loss of U.S. cost advantages, the

authors demonstrate cogently that cost problems had emerged

well before the dollar took off in the late 1970s. Like Grayson and

O’Dell, they cite figures demonstrating that U.S. productivity grew

at half the rate of Japan’s during the 1980s, and that this problem

was exacerbated by a relative decline in business investment.

Quality has posed even greater problems. U.S. manufacturers

quickly lost market share because consumers perceived their

goods as lower quality than Japanese goods. This is why the

United States has yielded leadership to the Japanese and the

Germans in many high-tech industries. Again, there has also been

a decline in R&D expenditures as a percentage of the GNP; only

1% of the federal government’s R&D budget went to promoting

industrial growth. Indeed, the United States now has a significant

“balance of patents” problem.

Hayes, Wheelwright, and Clark provide ten useful chapters to

guide U.S. managers in creating the “learning” organization—

manufacturing companies that are world class. And what better

way to begin than to review the prevailing capital-investment

process in the United States? As with a growing number of

business scholars, Hayes and his associates believe that the

modern capital-budgeting regime, with its emphasis on

discounted present value, has not served U.S. manufacturing well.

Discounted present-value methods fail to comprehend the

strategic implications of capital-budgeting decisions, especially

the ways investment gives employees opportunities to learn and

grow.

Companies that refuse to invest, they argue, fail to take into

account the impact of new technology on the organization’s

capabilities; they should bank on their organization’s ability to

achieve synergies that would be impossible without investment.

The key to a wise investment process revolves around the

achievement of a broadly “shared understanding of the

investment’s purpose and requirements…and the development of

a holistic understanding of how the investment relates to their

competitive mission.”

Once a sensible capital-budgeting process is developed, Dynamic

Manufacturing teaches, it is important that companies value the

manufacturing function. U.S. manufacturing companies

characteristically have created staff-heavy manufacturing

organizations in which commanding executives have too much

control. Manufacturing staff should be a “support group, not the

aristocracy of the manufacturing organization.”

Let us be clear, however. All of the failings of the old

manufacturing organization are symptoms. The disease,

according to Hayes and his associates, pertains to human factors,

“specifically, management factors—at least as much as it is due to

unfair competition or an unsupportive economic climate.” We are

experiencing industrial decline essentially because U.S.

manufacturing companies still operate within the paradigm of

Taylor and Ford. It is in this light that we encounter managers

obsessed with short-term profitability.

In a distinctive chapter, “The High-Performance Factory,” the

authors give wonderful glimpses of prevailing practices at new

and excellent manufacturing operations. They caution that new

investment imposes very high short-term costs on a factory, quite

apart from the costs of the newly invested capital, and they

conclude that new investment is not a viable solution for a

company that is in a “do or die” situation. They consider here and

elsewhere how the benefits of new investment come not in the

short term but over the long term. They consider product and

process development (their strongest suit), design for

manufacturability, the elimination of waste, and the reduction of

work in process.

The high-performance manufacturing organization is one that

can design a product correctly the first time—to reduce

significantly, if not eliminate, engineering change orders that can

cripple manufacturing productivity.

There is much more to Dynamic Manufacturing. This summary

has been only a taste. The point is that Hayes, Wheelwright, and

Clark believe knowledge to be the basis of a dynamically managed

factory. Are they right to suppose they depart, therefore, from

Taylor?

In fact, the authors often articulate their arguments in the

manner of Taylor. They write that, to achieve a dynamic learning

organization, “it is not simply a matter of changing a few things;

almost everything must be changed and changed dramatically.”

Taylor, remember, also stressed that the successful adoption of

his system required a complete mental revolution. There is the

same tone, the same kind of exhortation.

No doubt, we are talking about two revolutions here—the

presumably holistic revolution of Hayes, Wheelwright, and Clark

on the one hand and, on the other, Taylor’s command-and-

control revolution. But in both cases, the key is knowledge-based

manufacture, and the critical question is, who controls the

knowledge? The general goal is to push authority for the system of

manufacture into the hands of people in the organization most

competent to devise that system—and to help those people learn

more.

Nor is it true that Japanese factories are so very holistic. Think

about Japanese quality circles. Hayes and his associates

recommend QCs, but only after several preliminary steps have

been taken: “improving a factory’s basic housekeeping, correcting

its known short-comings, building its technological competence,

establishing a philosophy of continual improvement, [and]

getting workers’ inputs to process design issues.” Taylor believed

that just such steps were critical before the scientific manager

brought out the stopwatch, i.e., to calculate the one best way to do

a given manufacturing task.

Moreover, Sony, Matsushita, and Sanyo have recently said that

their U.S. factories are “not yet ready” for QCs—just as Taylor

argued that a foundry at Watertown Arsenal in Massachusetts was

not yet ready for the stopwatch. (It seems an overly zealous

disciple began time-and-motion studies and then watched the

foundry workers go on a wildcat strike, an action that resulted in

the banning of the Taylor system from all government facilities.)

True, if the Japanese-run American factories are ever ready for

QCs, one can envision the stopwatch in the hands of workers

themselves—or at least some workers—not managers. But just

because it is now line leaders and ambitious “associates” (Honda’s

euphemism for workers) who design ways to make work more

stringent, we can hardly conclude from this that factories have

become opportunities for worker self-realization. Hierarchy is still

a tragic fact of Japanese production, perhaps of all production.

Or consider Grayson and O’Dell turning their arguments on

Japanese manufacturers who have made profound changes in

productivity and quality at factories that were formerly run by

U.S. manufacturing firms. The sample cited is not big: Sanyo in

Arkansas and the Toyota-General Motors NUMMI plant in

Fremont, California are most conspicuous. Is there not room for at

least some skepticism here too?

Formerly, the GM Fremont plant had some 7,800 workers; now

under Toyota management, the plant produces more cars than

ever with only 2,500 workers. But if one looks carefully around

the plant, the ghosts of both Taylor and Ford appear. The 2,500

workers who eventually reentered the Fremont plant did so only

after management assessed their “fitness” for the new

manufacturing regime, that is, their willingness to accept—and

contribute to—rigorous new standards for timeliness and

performance. Scientific selection of workers is Taylor’s first

principle.

The Fremont plant under NUMMI is not identical to the Fremont

plant under General Motors, moreover. The level of automation

and computer control is far greater than before. The NUMMI

plant, like plants in Japan, is hardly a picnic ground for workers,

even if the floors are kept clean enough to eat off of. (Every visitor

to Ford’s Highland Park, Michigan plant between 1913 and 1915

remarked how spotless the place was.) Indeed, the great, initial

productivity gain was realized in the production of a single,

standardized model of the Chevrolet “Nova”—which reminds one

of Ford’s Highland Park plant in the era of the Model T. Workers

are tightly coupled with machines, and they don’t set their own

pace.

I like to think that the Japanese have not buried the paradigm of

Taylor and Ford, but have at once brought it to a new level of

refinement and wrapped it in a fresh mantle of respectability. The

Japanese may have pushed greater responsibility for the

strictures on operators down the line to the shop floor. Would that

have made any difference to Schmidt?

ABusiness

version Review.

of this article appeared in the November 1988 issue of Harvard

DH

David A. Hounshell was a Marvin Bower Fellow

at the Harvard Business School during the

academic year 1987–1988 and is professor of

history at the University of Delaware. He is the

author of From the American System to Mass

Production, 1800–1932 (Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1984) and coauthor of Science

and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R&D 1902–

1980 (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Recommended For You

Are Our Management Theories Outdated?

HBR Lives Where Taylorism Died

What Do Women's Career Paths Really Look Like?

Disappointment Makes You More Trusting: An Interview with Luis Martinez

You might also like

- Under New Management: How Leading Organizations Are Upending Business as UsualFrom EverandUnder New Management: How Leading Organizations Are Upending Business as UsualRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process Under Monopoly CapitalismFrom EverandManufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process Under Monopoly CapitalismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Kanigel Robert - Taylor The One Best Way (Review) - 1998 PDFDocument4 pagesKanigel Robert - Taylor The One Best Way (Review) - 1998 PDFMario PioNo ratings yet

- Let's Fix It!: Overcoming the Crisis in ManufacturingFrom EverandLet's Fix It!: Overcoming the Crisis in ManufacturingNo ratings yet

- John Taylor Gatto - Underground History of American EducationDocument20 pagesJohn Taylor Gatto - Underground History of American Educationjustgiving100% (4)

- The Management CenturyDocument15 pagesThe Management CenturySmriti MehtaNo ratings yet

- The Management CenturyDocument17 pagesThe Management CenturyMemes CreatorNo ratings yet

- Between Craft and Class: Skilled Workers and Factory Politics in the United States and Britain, 1890-1922From EverandBetween Craft and Class: Skilled Workers and Factory Politics in the United States and Britain, 1890-1922No ratings yet

- Reform or Repression: Organizing America's Anti-Union MovementFrom EverandReform or Repression: Organizing America's Anti-Union MovementNo ratings yet

- Alfred Marshall'sDocument25 pagesAlfred Marshall'snytNo ratings yet

- Full History Ia 4Document14 pagesFull History Ia 4api-373635046No ratings yet

- Special Book Review Section On The Classics of ManagementDocument3 pagesSpecial Book Review Section On The Classics of ManagementFirdaus PutraNo ratings yet

- Term Paper RawDocument157 pagesTerm Paper Rawasem_nsuNo ratings yet

- Frederick Winslow Taylor One Hundred Years of Managerial InsightDocument9 pagesFrederick Winslow Taylor One Hundred Years of Managerial InsightGian CarloNo ratings yet

- Experimental Capitalism: The Nanoeconomics of American High-Tech IndustriesFrom EverandExperimental Capitalism: The Nanoeconomics of American High-Tech IndustriesNo ratings yet

- Organizing America: Wealth, Power, and the Origins of Corporate CapitalismFrom EverandOrganizing America: Wealth, Power, and the Origins of Corporate CapitalismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Alfred Marshall S Critical Analysis of Scientific ManagementDocument25 pagesAlfred Marshall S Critical Analysis of Scientific ManagementbreathlightNo ratings yet

- Turning Men Into Machines Scientific Management, Industrial Psychology, and The "Human Factor"Document36 pagesTurning Men Into Machines Scientific Management, Industrial Psychology, and The "Human Factor"Willy K. Ng'etichNo ratings yet

- Answer No.1: Scientific Management Is A Theory of Management That Analyzes and Synthesizes WorkflowsDocument8 pagesAnswer No.1: Scientific Management Is A Theory of Management That Analyzes and Synthesizes Workflowsshahabuddin khanNo ratings yet

- Suntzuorsunziwasa: Scientific ManagementDocument7 pagesSuntzuorsunziwasa: Scientific Managementv_jamesamorNo ratings yet

- Taylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945From EverandTaylorism Transformed: Scientific Management Theory Since 1945Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Poor Man's Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950From EverandPoor Man's Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950No ratings yet

- Ohio State University Columbus, OhioDocument3 pagesOhio State University Columbus, OhiodaniNo ratings yet

- Frederick Winslow TaylorDocument6 pagesFrederick Winslow TaylorVinod BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of the Middle Class: Work and Politics Among American EngineersFrom EverandMechanics of the Middle Class: Work and Politics Among American EngineersNo ratings yet

- Vienna & Chicago, Friends or Foes?: A Tale of Two Schools of Free-Market EconomicsFrom EverandVienna & Chicago, Friends or Foes?: A Tale of Two Schools of Free-Market EconomicsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Principals, Producers, & Planners: How to Live Rich WellFrom EverandPrincipals, Producers, & Planners: How to Live Rich WellNo ratings yet

- Management and Ideology: The Legacy of the International Scientific Management MovementFrom EverandManagement and Ideology: The Legacy of the International Scientific Management MovementNo ratings yet

- From Taylorism To Neo-Taylorism: A 100 Year Journey in Human Resource ManagementDocument18 pagesFrom Taylorism To Neo-Taylorism: A 100 Year Journey in Human Resource ManagementIgor BluesNo ratings yet

- The Right and Labor in America: Politics, Ideology, and ImaginationFrom EverandThe Right and Labor in America: Politics, Ideology, and ImaginationNo ratings yet

- The Essence of Mill's Economics: Principles of Political Economy, Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy, Socialism & The Slave PowerFrom EverandThe Essence of Mill's Economics: Principles of Political Economy, Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy, Socialism & The Slave PowerNo ratings yet

- Summary and Analysis of The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century: Based on the Book by Thomas L. FriedmanFrom EverandSummary and Analysis of The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century: Based on the Book by Thomas L. FriedmanRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American CapitalismFrom EverandThe Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American CapitalismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Frederick Winslow TaylorDocument10 pagesFrederick Winslow TaylorDiah GembulNo ratings yet

- Frederick Winslow Taylor, Father of Scientific ManagementDocument9 pagesFrederick Winslow Taylor, Father of Scientific ManagementGayaz SkNo ratings yet

- England's Great Transformation: Law, Labor, and the Industrial RevolutionFrom EverandEngland's Great Transformation: Law, Labor, and the Industrial RevolutionNo ratings yet

- The Enlightened Capitalists: Cautionary Tales of Business Pioneers Who Tried to Do Well by Doing GoodFrom EverandThe Enlightened Capitalists: Cautionary Tales of Business Pioneers Who Tried to Do Well by Doing GoodRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Organizing Locally: How the New Decentralists Improve Education, Health Care, and TradeFrom EverandOrganizing Locally: How the New Decentralists Improve Education, Health Care, and TradeNo ratings yet

- After the Education Wars: How Smart Schools Upend the Business of ReformFrom EverandAfter the Education Wars: How Smart Schools Upend the Business of ReformNo ratings yet

- Frederick W TaylorDocument9 pagesFrederick W TaylorMutua AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Spinning Masters Account or The Theory and Practice of Cotton Spinning Made HimDocument11 pagesSpinning Masters Account or The Theory and Practice of Cotton Spinning Made HimDian Weleh-welehNo ratings yet

- Frederick Winslow TaylorDocument6 pagesFrederick Winslow TaylorAngela AllenNo ratings yet

- Witzel Where Scientific Management Went AwryDocument4 pagesWitzel Where Scientific Management Went Awrychathuranga_bandara_100% (1)

- Ted Talk SpeechDocument8 pagesTed Talk Speechapi-665595119No ratings yet

- The Development of Personnel Management in The United StatesDocument20 pagesThe Development of Personnel Management in The United StatesPedro Alberto Herrera LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Wal-Mart: The Face of Twenty-First-Century CapitalismFrom EverandWal-Mart: The Face of Twenty-First-Century CapitalismRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (17)

- Cell # 03135592853, 03435693853Document11 pagesCell # 03135592853, 03435693853Rafi KashmiriNo ratings yet

- FW Taylor 1Document3 pagesFW Taylor 1AXL REYHAN PRASETYONo ratings yet

- 15 Years, 50 ClassicsDocument6 pages15 Years, 50 ClassicsmcolemanscrNo ratings yet

- The Speculation Economy: How Finance Triumphed Over IndustryFrom EverandThe Speculation Economy: How Finance Triumphed Over IndustryNo ratings yet

- American Industrial Revolution Research PaperDocument6 pagesAmerican Industrial Revolution Research Paperfvgczbcy100% (1)

- Enterprise and State in The West German Wirtschaftswunder - Volkswagen and The Automobile Industry, 1939-1962Document81 pagesEnterprise and State in The West German Wirtschaftswunder - Volkswagen and The Automobile Industry, 1939-1962interval84No ratings yet

- Doing History from the Bottom Up: On E.P. Thompson, Howard Zinn, and Rebuilding the Labor Movement from BelowFrom EverandDoing History from the Bottom Up: On E.P. Thompson, Howard Zinn, and Rebuilding the Labor Movement from BelowRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Greed, Inc.: Why Corporations Rule the World and How We Let It HappenFrom EverandGreed, Inc.: Why Corporations Rule the World and How We Let It HappenNo ratings yet

- Establishing Your Asset Performanсe Management ProcessDocument3 pagesEstablishing Your Asset Performanсe Management ProcessAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- How Good Is Your BenchmarkingDocument5 pagesHow Good Is Your BenchmarkingAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- The Death of Supply Chain ManagementDocument6 pagesThe Death of Supply Chain ManagementAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Benchmarking Outside The BoxDocument6 pagesBenchmarking Outside The BoxAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Quantifying The Financial Benefits of QualityDocument5 pagesQuantifying The Financial Benefits of QualityAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Measuring and Demonstrating The Value of Quality InitiativesDocument2 pagesMeasuring and Demonstrating The Value of Quality InitiativesAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Innovation Management and The Knowledge-Driven EconomyDocument163 pagesInnovation Management and The Knowledge-Driven EconomyAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Organizational Performance MeasuresDocument60 pagesOrganizational Performance MeasuresAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Garad - The Effective Quality ManagerDocument14 pagesGarad - The Effective Quality ManagerAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide To Reading The Cumulative Flow DiagramDocument27 pagesThe Ultimate Guide To Reading The Cumulative Flow DiagramAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- COOP Template Business Continuity PDFDocument26 pagesCOOP Template Business Continuity PDFsunimedichuNo ratings yet

- A Review On The Classification of Total Quality ManagementDocument20 pagesA Review On The Classification of Total Quality ManagementAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- How To Manage A Modern Warehouse WorkforceDocument13 pagesHow To Manage A Modern Warehouse WorkforceAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- A Driving Force in The Knowledge EconomyDocument10 pagesA Driving Force in The Knowledge EconomyAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- The Origins and Evolution of Lean Management SysteDocument6 pagesThe Origins and Evolution of Lean Management SysteAditya SoniNo ratings yet

- Data, Insights, Action: Transforming The Customer ExperienceDocument9 pagesData, Insights, Action: Transforming The Customer ExperienceAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Iannone and Elena - 2013 - Managing OEE To Optimize Factory PerformanceDocument20 pagesIannone and Elena - 2013 - Managing OEE To Optimize Factory PerformanceAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Toyota Process Flow Analysis: ToyotaprocessflowanalysisDocument5 pagesToyota Process Flow Analysis: ToyotaprocessflowanalysisRoel DavidNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Management McnaughtonDocument4 pagesPortfolio Management McnaughtonadityaNo ratings yet

- Iannone and Elena - 2013 - Managing OEE To Optimize Factory PerformanceDocument20 pagesIannone and Elena - 2013 - Managing OEE To Optimize Factory PerformanceAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Barry - Elliott - Oliver - Wight - Asia - Pacific - Planning CapacityDocument36 pagesBarry - Elliott - Oliver - Wight - Asia - Pacific - Planning CapacityAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Project Management McnaughtonDocument4 pagesProject Management McnaughtonAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Product Management Review McnaughtonDocument4 pagesProduct Management Review McnaughtonAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Integrated Product Portfolio Project MGMT Reiher ShanahanDocument12 pagesIntegrated Product Portfolio Project MGMT Reiher ShanahanAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Integrating Product Management into the Business Planning ProcessDocument12 pagesIntegrating Product Management into the Business Planning ProcessAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Driving Excellence Product Management - 0Document12 pagesDriving Excellence Product Management - 0Andrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Product Management Mcnaughton - 0Document4 pagesProduct Management Mcnaughton - 0Andrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

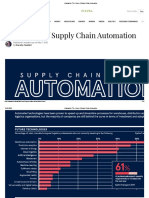

- The Future of Supply Chain AutomationDocument15 pagesThe Future of Supply Chain AutomationAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Operational Excellence: An Examination ofDocument26 pagesOperational Excellence: An Examination ofAndrey MatusevichNo ratings yet

- Target: Managing Operations To Create Competitive AdvantageDocument15 pagesTarget: Managing Operations To Create Competitive Advantageagreen89No ratings yet

- 12 PIllars of CompetitivenessDocument12 pages12 PIllars of CompetitivenessLyn EscanoNo ratings yet

- Bayer Pharma RD Event 2023Document135 pagesBayer Pharma RD Event 2023ranvijay.rajput515No ratings yet

- FIL - Warren Buffett and Interpretation of Financial Statements PDFDocument33 pagesFIL - Warren Buffett and Interpretation of Financial Statements PDFchard serdenNo ratings yet

- Nike PESTLEDocument11 pagesNike PESTLEAngelu Amper100% (2)

- LOREALDocument2 pagesLOREALRukhsar Abbas Ali .No ratings yet

- Wipo Pub Gii 2020-Chapter1Document40 pagesWipo Pub Gii 2020-Chapter1DuarteNo ratings yet

- Gourmet FinalDocument33 pagesGourmet Finalrizwanhafsa50% (4)

- Roland Berger Trend Compendium 2030Document49 pagesRoland Berger Trend Compendium 2030gabrinaNo ratings yet

- Met466 Module 3 NotesDocument12 pagesMet466 Module 3 NotesFarhan Vakkeparambil ShajahanNo ratings yet

- 2018 Global R D Funding ForecastDocument43 pages2018 Global R D Funding ForecastYU DANNI / UPMNo ratings yet

- Lakme - Full PaperDocument12 pagesLakme - Full PaperSoumya RanjanNo ratings yet

- ءاذغلاو ةعارزلا جمانرب Call no. 2/2019/ASRT-Agriculture Application FormDocument8 pagesءاذغلاو ةعارزلا جمانرب Call no. 2/2019/ASRT-Agriculture Application Formehab IbrahemNo ratings yet

- Group Case Study SyngentaDocument13 pagesGroup Case Study SyngentaNUR ZULAIKHA ATIQAH ZAHRAH ABD RAHIMNo ratings yet

- AGILE Methologics Set 1Document2 pagesAGILE Methologics Set 1nvsrinivasan1991No ratings yet

- About UsDocument3 pagesAbout UsKrishna SinghNo ratings yet

- The Handbook of Innovation and Services A Multi-Disciplinary PerspectiveDocument822 pagesThe Handbook of Innovation and Services A Multi-Disciplinary Perspectiveflaviomanoel100% (1)

- Nanotech Insights July 2011 Issue-Draft-1st Sept, 2011 PDFDocument52 pagesNanotech Insights July 2011 Issue-Draft-1st Sept, 2011 PDFsophia raniNo ratings yet

- Finland As A Knowledge Economy - Carl J Dahlman - Jorma RouttiDocument136 pagesFinland As A Knowledge Economy - Carl J Dahlman - Jorma Routtim_kv1363No ratings yet

- Strategic Advantage ProfileDocument3 pagesStrategic Advantage Profilezakirno19248100% (1)

- 2017 Innovation Benchmark Findings PDFDocument21 pages2017 Innovation Benchmark Findings PDFAndré Toga Machado CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Renewal of OrganizationsDocument15 pagesStrategic Renewal of OrganizationsMichael LeungNo ratings yet

- SM-I Shubham Sharma MBA06145Document9 pagesSM-I Shubham Sharma MBA06145Shubham SharmaNo ratings yet

- Global value chains, an opportunity or strainDocument3 pagesGlobal value chains, an opportunity or strainKieran Ross-StubbsNo ratings yet

- Lectura - Capitulo 2 - UnlockedDocument16 pagesLectura - Capitulo 2 - UnlockedMiguel Angel Delgado ArandaNo ratings yet

- Ernst & Young Report Analyzes Global Biotech Industry Performance and ChallengesDocument37 pagesErnst & Young Report Analyzes Global Biotech Industry Performance and ChallengesRadhika BhattadNo ratings yet

- Parameters of Success - Moser Baer India LimitedDocument2 pagesParameters of Success - Moser Baer India LimitedshrutikapoorNo ratings yet

- Improve Pakistan's Soap IndustryDocument4 pagesImprove Pakistan's Soap IndustryMuhammad Abdullah0% (1)

- Annual Report - 2019 - en PDFDocument169 pagesAnnual Report - 2019 - en PDFNipun SahniNo ratings yet

- NikeDocument14 pagesNikeLaiba emanNo ratings yet