Professional Documents

Culture Documents

International Factors in The Formation of Refugee Movements

Uploaded by

Marie DupontOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

International Factors in The Formation of Refugee Movements

Uploaded by

Marie DupontCopyright:

Available Formats

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements

Author(s): Aristide R. Zolberg, Astri Suhrke and Sergio Aguayo

Source: International Migration Review, Vol. 20, No. 2, Special Issue: Refugees: Issues and

Directions (Summer, 1986), pp. 151-169

Published by: The Center for Migration Studies of New York, Inc.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2546029 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 08:14

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Center for Migration Studies of New York, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to International Migration Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the

Formation of Movements

Refugee

Aristide R. Zolberg

Graduate Faculty, New School for Social Research

Astri Suhrke

School of International Service, American University

Sergio Aguayo

El Colegio de Mexico

On the basis of detailed case studies by the authors of the principal re?

fugee flows generated in Asia, Africa, and Latin America from approx?

imately 1960 to the present, it was found that international factors often

intrude both directly and indirectly on the major types of social conflict

that trigger refugee flows, and tend to exacerbate their effects. Refugees

are also produced by conflicts that are manifestly international, but

which are themselves often related to internal social conflict among the

antagonists. Theoretical frameworks for the analysis of the causes of

refugee movements must therefore reflect the transnational character

of the processes involved. This paper sets forth such a framework and

points to the policy implications of the proposed reconceptualization.

REFUGEES IN TRANSNA TIONAL PERSPECTIVE1

The definition of refugees in general international law embodies an "in?

ternalist" vision whose validity is challenged by contemporary realities. The

usual criterion, ie., determination that the persons in question crossed an

international frontier as a consequence of a "well-founded fear of persecution",

implies that such fear is occasioned by an agent located within the country of

origin. This is confirmed by other considerations. Refugees within the

mandate of UNHCR also include persons outside their own country who can

be determined to be without, or unable to avail themselves of, the protection

of the government of their state of origin; but in such cases, as pointed out in

a recent authoritative work, it is essential that "the reasons for flight should

be traced to conflicts, or radical political, social, or economic changes in

their own country" (Goodwin-Gill, 1983:18).

1This article is based on research conducted

by the authors under a grant from the Ford and

Rockefeller Foundations. Detailed case studies that substantiate our argument will be published

in a forthcoming larger work. For an example of our approach, see, A. Suhrke and A. Zolberg,

"Social Conflict and Refugees in the Third World: The Cases of Ethiopia and Afghanistan"

IMR Volume xx, No. 2 151

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

152 International Migration Review

The operative term here is "in their own country". From a legal perspective,

what matters is where the conflict itself takes place, with little concern for the

location of its causes; nevertheless, since international law is founded on the

of ? i.e., on the notion that the world is divided into a

concept sovereignty

finite set of states with mutually exclusive jurisdiction over segments of

and clusters of ? the definition in effect assumes that

territory population

the determinants of persecution are also internal to the appropriate state.

Against this, it is evident that factors originating outside the source country

of a given group of refugees commonly play an important role in triggering

the flow and in determining its course. This is manifestly the case in the

situations that together account for the majority of current, officially

recognized Third World refugees, including those encountered in the Horn

of Africa, Chad, Southern Africa, Afghanistan, and Southeast Asia; and it is

applicable as well to most of the largely unrecognized claimants in and from

Central America.

Some of these realities have begun to be acknowledged at the level of

international law, as demonstrated by the Organization of African Unity's

1969 Convention on Refugee Problems in Africa, whose Article I begins with

a restatement of the established U.N. definition centered on persecution,

and then adds:

2. The term 'refugee' shall also apply to every person who, owing to

external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously

disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of

origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his place of habitual

residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his country

of origin or nationality (Goodwin-Gill, 1983:281).

Although this article came into existence largely as an expression of political

solidarity on behalf of the then ongoing struggles against white rule in

southern Africa, it is generally relevant to our theoretical argument because,

by adding various types of foreign intervention and "events seriously

disturbing public order" to persecution as triggers, it points to the possibility

of formulating a general definition of refugees, anchored in a realistic

consideration of the processes that account for an already large and probably

growing share of people from the Third World who are outside of their

country and deprived of its protection.

(paper presented at the Center for Population Studies, Harvard University, 1984). We are

grateful to the Refugee Policy Group for providing an opportunity to present a preliminary

version of this paper to a critical audience at a workshop in Washington, D.C, in the spring of

1985, and to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions. This article was also

presented in different form at the World Congressof the International Political Science Association

in Paris, July 1985. Due to unforeseen circumstances and deadline pressures, final revisions were

made by A. Zolberg without consultation of the other co-authors.

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 153

In short, for purposes of social scientific analysis, refugees can be defined

as persons whose presence abroad is attributable to a well-founded fear of

violence, as might be established by impartial experts with appropriate

information. In cases of persecution covered by the classic definition, the

violence is initiated by some recognizable internal agent, such as the

government, and directed at a specified target group; the presence of members

of the group abroad may be the result of flight to avoid harm, or of expulsion,

itself a form of violence. But flight-inducing violence may also arise as an

incidental consequence of external or internal conflict, or some combination

of both, and affect groups that are not even parties to that conflict.2

Although only one of the triggers of violence mentioned is itself manifestly

international, factors external to the country from which the refugees originate

can contribute to both of the other two. And because the presence of such

factors constitutes the norm rather than the exception, it is appropriate to

think of refugee-formation as a transnational process.

Refugee movements thereby reflect a fundamental characteristic of the

contemporary world, namely its transformation into an interconnected whole

within which national societies have been profoundly internationalized.

Moreover, the effects under consideration do not constitute a collection of

random events but occur in the form of distinct patterns; and these can be

related in turn to the patterns of social conflict that foster refugee movements.

Today as in the past, these conflicts tend to arise in the course of two major

types of political transformations: abrupt changes of regime, particularly

social revolutions as well as the responses of incumbents to revolutionary

challenges, and the reorganization of political communities, particularly the

formation of new nation-states out of former colonial empires (Suhrke, 1983;

Zolberg, 1983a, 1983b).

Albeit usually considered as essentially "internal", these types of conflicts,

which trigger the classic situations of recognized refugees, often include an

element of foreign intervention. It is notorious that the various camps

2Whereas for legal and administrative

purposes it is usually necessary to establish dichotomous

categories (refugees and non-refugees), for the purposes of sociological analysis the concept of

refugee can be thought of as a variable on the basis of an index of danger, which might combine

the magnitude of the threat with the probability of its occurrence, as suggested by Patricia W.

Fagen in an oral comment on an earlier version of this paper. The set of people constituted on the

basis of this approach contains sub-categories involving different degrees of "refugeness"; it

includes people who are not currently recognized as refugees by relevant governments (e.g.,most

Salvadoreans in the United States), while excluding some who are {e.g., many Soviet Jews,

Cubans, and Vietnamese). It is hardly necessary to stress that we do not mean to suggest thereby

that people who do not appear in the set should be denied the right to leave their country, or not

be welcomed in the United States or elsewhere. It should be noted, incidentally, that the use of

violence as a definitional criterion makes it possible to distinguish refugees from persons who are

abroad as a consequence of natural disaster; victims of famine are refugees if the famine is itself

attributable to violence, as in the case of confiscatory economic measures (e.g., British land

policies in Ireland from the XVIIth century onward) or extremely unequal property systems

maintain by brutal force.

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

154 International Migration Review

involved in revolutionary confrontation more often than not receive

significant support from abroad, ranging from encouragement to outright

armed intervention; in some cases, that support is determinative of the

outcome. Much the same can be said concerning nation-formation, which

often involves a clash between the state nationalism of a politically dominant

group vs. the nationalist aspirations of ethnic minorities; but the country's

neighbors usually have stakes in the conflict as well, since their own integrity

is likely to be affected by the outcome.

In addition to the manifest form of deliberate intervention by outsiders in

internal conflicts, external effects also occur more indirectly, in the form of

factors that exacerbate social and economic conditions, thereby rendering

the eruption of refugee-generating conflicts more likely. A variety of

"dependency" theorists have asserted that processes emanating from the

capitalist world economy constitute the root causes of both economic and

political underdevelopment; although the validity of such comprehensive

claims is questionable, there is little doubt that the world economy as presently

constituted is indeed a source of severe difficulties for latecomers.

The most problematic type of external effect consists of the policies of

potential receivers. The starting point here is that for a given flow of

refugees to come into being, certain conditions must be met in one or more

states of destination as well as in a state of origin. In the course of earlier

presentations, this assertion was deemed objectionable by some members of

the refugee policy community as it appears to suggest that those who aid

refugees are as much to blame as those who occasion the flows. But that is not

at all the point; upon reflection, the assertion can be seen as a trusim that

holds for all types of international migration. People cannot leave their

country if they have no place to go; and in effect, in a world of generally

restrictive controls on entry, the availability of such a place is largely

determined the of receivers ?

by governmental policy including potential

receivers, since the policy can be negative (Zolberg, 1981).

This does not mean that official authorities or others in the state of origin

deliberately take into consideration the availability of a place of refuge

before engaging in persecution and the like; but other things being equal,

the availability of a place of refuge may in some cases determine whether

persecution will lead to the formation of a refugee flow or to some other

outcome, such as mass murder, which can be thought of as a form of extreme

persecution that does not produce refugees.3

3The case referred to is of course that of the

European Jews during the Nazi era. There is little

doubt that the original objective of the Nazis with respect to Jews within Germany, and later

within the Europe they controlled, was expulsion; and the unwillingness of liberal democracies

to take in Jewish refugees is well documented also. What is less clear is the precise role which the

unavailability of an alternative place for the Jews played in fostering a shift of Nazi policy to the

"Final Solution" (Arendt, 1973; Wyman, 1984). Non-cases contribute to the understanding of

actual cases by highlighting elements of their configuration. For example, although the war in

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 155

The receivers can also make a positive contribution to the formation of

refugee flows, for example by admitting as refugees persons who would not

qualify under the prevailing U.N. definition;4 and such a generous policy

tends to act as a "pull" factor, leading some people to uproot themselves who

might not have done so otherwise. A similar effect might result from a

restrictive policy that is poorly enforced, or opposed by some significant

groups within the receiving country.5 It is therefore reasonable to suggest,

more generally, that the refugee policies of potential or actual receivers

function as an external factor influencing both the magnitude and the

direction of refugee movements.

Although refugee policy is shaped in part by domestic concerns, it lends

itself to many uses as an instrument of foreign policy, and therefore

considerations arising from this sphere are usually determinative. The

decision to bestow formal refugee status in accordance with the U.N.

Convention to citizens of a particular state usually implies condemnation of

the relevant government for persecuting its citizens, or at least failing to

afford them protection. A generous admission policy toward a certain group

enourages them to leave; not only can this be used propagandistically to

claim the people are "voting with their feet", but the outflow of certain

socioeconomic groups may also weaken the country of origin in a more

material sense. The traditional post-World War policy of the U.S. toward

citizens of communist countries, starting with Eastern Europe and China,

and then going on to Cuba and Indochina, was explicitly founded on such

considerations.6 Concomitantly, friends and allies can be helped through

burden-sharing of refugee inflows. Conversely, support for a government

normally implies denial of refugee status to its nationals, as illustrated by

U.S. behavior in the cases of post-Allende Chile, as well as El Salvador and

Guatemala today.

East Timor has caused very considerable destruction and suffering for almost a decade, it has

generated almost no refugees. This is because the conflict has received relatively little international

attention and the East Timorese resistance has not acquired foreign patrons, while the occupying

power, Indonesia, has powerful friends.

4The major illustration is U.S.

policy toward Communist countries in the post-World War II

period, initially with respect to Europe and later with respect to Cuba and Vietnam. Once again,

to avoid misunderstandings, we stress that this observation does not involve judgment on our

part.

5The current flow of Salvadoreans into the United States, as well as continued movements of

Indochinese peoples into SoutheastAsian countries whose governments had instituted a "humane

deterrence" against further entry illustrate how various combinations of these factorscan operate

to frustrate official policy.

6 A National Security Council document of 1953

put the case bluntly, stating that it is U.S.

policy to "encourage defection of all U.S.S.R. nationals as well as of 'key' personnel from the

satellite countries", justifying it on the grounds that defection "inflicts a psychological blow on

Communism", "counters Communist propaganda*in the Free World", and "though less im?

portant, the material loss to the Soviet bloc is also significant" (NSC, 1953).

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

156 International Migration Review

The most extreme uses of refugee policy in the service of foreign policy

involve aiding exile communities that engage in military action against the

government of their country of origin. The classic case here is Arab support

for Palestinians, and the related decision not to integrate them in the receiving

countries since doing otherwise would serve to legitimize the existence of

Israel. Prominent recent instances include communities supported by the

United States or its allies: Afghans in Pakistan, Khmer on the Thai-

Kampuchea border, Nicaraguan contras on the border between Nicaragua

and Honduras. But the practice is by no means limited to one of the major

world camps, as indicated by Algerian support for Polisario guerillas claiming

the Western Sahara; use by Libya of northern Chadians in operations against

Chad; the complex interrelated cases involving Sudanese sanctuary for

anti-Ethiopian Eritreans (who receive military support from a variety of

Arab sources), and Ethiopian sanctuary for Sudanese secessionists; and the

grant of sanctuary by Iran to Afghan rebels.

The proposition that external factors play an important role in the

determination of contemporary refugee flows is thus well substantiated. But

although the above illustrations were drawn from the current or recent

scenes, it is evident that for each of the patterns indicated, one could also

muster a number of examples from the more remote past. In one sense, this

generally strengthens the point, as it can be seen to apply to the past as well as

to the present. But in another sense, the general observation thereby loses

some of its value in relation to the analysis of the present. It is therefore

necessary to specify further what is distinctive about the contemporary

situation. This requires a consideration of the global configuration that

generates the effects with which we are concerned.

GLOBAL STRUCTURES AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES

The transnational perspective adopted here is grounded in the notion that

the globe constitutes a comprehensive field of social interaction, concept?

ualized as a network of interdependent political and economic structures,

but with some autonomy in relation to each other.7 What follows is of

necessity a broad summary account of those aspects of the global social field

that are especially relevant for the present purpose.

Although the origins of the contemporary world's political and economic

structures can be traced to the late Middle Ages (XVth-XVIth centuries), it

was only in the latter part of the XXth that they became truly global in scope.

7 It

might be noted that this conceptualization bears a family relationship to I. Wallerstein's

"world-system"(1974, 1979), but differs significantly from it, particularly in that we eschew the

functionalist notion of "system", and also recognize the existence of an international system of

states that generates distinctive politico-strategic processes with a dynamic of their own (Zolberg,

1981, 1983). Relevant works include Keohane and Nye (1972), Barraclough (1969), and Bull and

Watson (1984).

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 157

This resulted from a combination of distinct, albeit related, processes. First,

the breakup of the remaining traditional empires and of the more recent

colonial realms created in the process of European expansion resulted in the

emergence of a large number of new states, mainly in Asia and Africa. These

were integrated into an existing international system whose units consisted

of mutually exclusive nation-states exercising nominal equality at the level

of international law. Secondly, at about the same time, the last remaining

economically self-sufficient zones were incorporated into a global network of

trade and production organized along capitalist lines, and subject to all of

the processes engendered by these activities. This is true even of countries

whose states attempted to develop structurally distinct and autarchic economic

systems. Thirdly, partly as a consequence of the preceding, all parts of the

globe came to be linked into a single network of extremely rapid com?

munication, within which one can distinguish the emergence of elements of

a common culture ? the As a consequence of this, in?

"global village".

formation concerning events in one part of the world is readily transmitted

to other areas, and can play a role in events in those distant places as well.

Despite nominal equality among states at the level of international law

and talk of an "international community", the global network that came into

being is founded on enormous asymmetries of power and wealth, and exhibits

distinctively anomic features. In the political sphere, the absence of a central

mechanism of conflict-regulation allows competitive and conflictual forces

relatively free play. At the center, the balance of terror has fostered some

stability and restraint in the bilateral relations of the superpowers; and this

further governs relations within and between their respective European

alliances, encompassing the industrialized countries of the Pacific Basin

region as well.

But in sharp contrast with this, the periphery, which constitutes the largest

? both in terms of the number of states

segment of the global political system

involved and the share of population ? is

they contain subject to severe

instability and conflict. The expansion of the international politico-strategic

system to encompass the entire globe implies that even the poorest and

geopolitically least significant of states acquired some value as stakes in the

politico-strategic games of the major players. It follows that internal regime

changes among Third World countries tend to be perceived as having

implications for the wider system, and are therefore likely to provoke some

sort of response by outsiders. Intervention occasionally takes the brutal form

of military action ? direct or by way of substitutes ? but more

commonly

occurs in the less manifest form of pressure on political elites to maintain or

adopt a particular ideological orientation, often using economic and military

assistance as the carrot, and its withholding as the stick.

In many parts of Asia and Africa, the engagement by several neighboring

states simultaneously in the formation of national communities provides an

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

158 International Migration Review

additional source of international tension because this sometimes involves

conflicting claims over the allegiance of certain ethnic groups and the

territory they inhabit. This process, which may be termed "competitive

state formation", provides the makings of the third of the patterns mentioned.

It is widely acknowledged that the difficulties inherent in the formation of

nation-states and the achievement of sustained economic growth are com?

pounded among contemporary Third World countries by such factors as

rapid demographic expansion, low resource endowment, undeveloped

human capital, extreme ethnic heterogeneity, and the like; but a variety of

"dependency" theorists have asserted further that the difficulties attributable

to internal givens are overshadowed by those emanating from the capitalist

world economy, and some have gone so far as to claim that processes

originating at that level constitute the root causes of both economic and

political underdevelopment. Although the comprehensive claims of de?

pendency theory are questionable, there is little doubt that most Third

World countries exhibit structural distortions that stem from their in?

corporation into the global economic system in the first instance as primary

producers, usually within the confines of a particular imperial or quasi-

imperial system of preference. With no choice but to participate in the global

economy on disadvantageous terms, they tend to experience effects such as

inflation, fluctuations in commodity markets, and unemployment in

amplified form, while reaping but a small share of benefits. This has the

effect not only of constraining these countries' choices of development

strategies but, by perpetuating and in some cases even worsening already

unfavorable conditions, of exacerbating the tensions and conflicts that are

inherent in major economic and political transformations.

REFUGEES AND SOCIAL REVOLUTIONS

Social revolutions involve a radical and rapid redistribution of economic,

social, and concomitant political power among social classes and groups

within largely agrarian societies marked by extreme structural inequality.

Although these conditions were historically commonplace in many parts of

the world, in the past social revolutions were relatively infrequent because

they require as well an initial weakening of the existing state by some

extraneous factors such as defeat in war (Paige, 1975; Skocpol, 1979). Within

most of the contemporary Third World, however, the state was not forged in

the course of a lengthy historical interaction with predatory neighbors, but

came into being by way of a process of decolonization, involving relatively

limited struggle, and hence is often weak to start with.

Extreme structural inequality prevails in most of Latin America and parts

of Asia, so that revolutionary challenges are likely to continue arising in

those regions in the foreseeable future. While most states of black Africa are

weak as well, they lack the social formation that is conducive to social

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 159

? i.e., a

revolution quite highly integrated society with a land-based class

system (Freund, 1984); upheavals are therefore more likely to take the form

of localized uprisings and perennial coups (Zolberg, 1967). Ethiopia is the

exception that confirms the rule, since its pre-revolutionary social organ?

ization was more like that of medieval Europe or many parts of Asia (Markakis

and Ayale, 1978).

All successful revolutions, as well as most attempted ones, have produced

major refugee movements. Historical cases include not only the French and

Soviet revolutions but also the American, whose numerous Tory refugees

went mostly to England and the western part of British North America (later

Ontario). In only one of these three cases was there a return movement, in

consequence of a successful counter-revolution. The Mexican Revolution of

1910 produced substantial population flows toward the United States, and in

1949 Chinese Kuo Min Tang supporters took over an entire island, which

had only recently been returned to China after half a century of Japanese

rule. Similarly, contemporary conflicts in Kampuchea, Vietnam, Ethiopia,

Iran, Afghanistan, Cuba, and Nicaragua, have accounted for a very large

part of the recognized international refugee population in recent years; and

the definition used here would produce a large pool as well, albeit somewhat

differently constituted.

This type of conflict almost always entails a significant element of foreign

involvement because of the linkages in the global state system between

regime orientation and international alignments. Established ruling classes

have external allies and supporters among the states arrayed in defense of

the status quo; conversely, revolutionaries tend to have links with those who

challenge the existing international order. In particular, revolutionary

conflicts attract the attention of the superpowers because ideological solidarity

is an instrument of international hegemony.

To state the obvious, U.S. governments tend to oppose revolutions while

Soviet governments tend to be favorably disposed toward them. In both

instances, intervention to defend an incumbent government against a

revolutionary challenge or to promote a revolutionary movement is more

likely if the country involved possesses some strategic significance; but it

should be noted that "strategic" is a highly flexible concept ? why, for

example, was Vietnam strategic from the point of view of the United States,

whereas Afghanistan is not?

Refugees are generated in the first instance by the generalized violence

and dislocation which typically accompany the onset of the revolutionary

process itself, regardless of its ultimate outcome. At a later stage, generalized

violence may recur if counter-revolutionary forces succeed in establishing

themselves in a position to challenge the consolidation of the revolution.

Second, the outcome itself will produce certain types of outflow. If the

revolution succeeds, it is likely to generate first a wave consisting of the old

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

160 International Migration Review

ruling classes and their associates; and subsequently, people who are

negatively affected by the exigencies of revolutionary reconstruction. If the

revolution is contained or reversed, however, the resulting regime is likely

to take an authoritarian form and institute repressive measures against

partisans of the revolution. Related to this, refugee flows may be occasioned

by the repressive policies of authoritarian regimes that seek to prevent the

emergence of a revolutionary movement in the first place (e.g., Guatemala).

In cases of successful revolutions, the elite wave is likely to be numercially

small, often consisting of people who manage to bring out independent

means of support ? or have taken the precaution of amassing some savings

abroad against an eventuality such as they now face ? and always have at

least nominal foreign patrons. They easily qualify for refugee status under

the U.N. Protocol and experience little difficulty in finding countries of

asylum. However, the second outflow is more problematic. Although the

policies pursued by revolutionary regimes are in principle designed to effect

redistribution, the government is often led to impose great sacrifices on the

population in order to extract the resources needed for social investments;

this is exacerbated by the fact that such policies are generally carried out in a

hostile international economic environment. Under these circumstances, a

very large number of people may seek to leave, provided they have minimal

assurance of finding reasonable resettlement elsewhere; since it suits the

foreign policy of states that oppose the revolution to demonstrate it lacks

support, they are likely to provide the necessary havens, and refugee flows

will materialize accordingly. The cases of Vietnam and Cuba exemplify this

mechanism, although in both cases, post-revolutionary problems were

intensified by other factors as well.

A variation on the scenario occurs when the problems of revolutionary

reconstruction are compounded by the military operations of counter?

revolutionary forces. The resulting insecurity and added impositions by the

revolutionary regime, especially military mobilization, cause additional

people to leave; these flows are encouraged by the counterrevolutionaries

and their patrons because they provide a source of military manpower as

well. The Nicaraguan case provides a partial illustration of this dynamic;

although the formation of a second wave may have been hampered by the

reluctance of the United States to admit Nicaraguans as refugees ? following

negative domestic reactions to the massive admission of Cubans and Indo-

Chinese in 1980 ? there are signs that it is emerging as a consequence of the

Sandinista draft. The dynamic is relevant to Angola and Mozambique as

well, where counterrevolutionary forces have been supported by the Republic

of South Africa.

Direct military intervention by external actors, or substantial military

contributions from them, works in the same direction, but with much greater

intensity because they provide the antagonists with additional firepower,

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 161

and hence result in an enlargement of the fire zone, without fostering the

formation of a social base and legitimacy which are necessary to conclude a

conflict that concerns the very foundation on which society should be

constructed. Recent examples that have resulted in large refugee flows

include Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, Soviet and Cuban intervention

in Ethiopia (initially in relation to the Ethiopia-Somalian war, but subse?

quently in relation to internal conflicts within Ethiopia), and U.S. assistance

to the government of El Salvador.

REFUGEES AND THE REORGANIZATION

OF POLITICAL COMMUNITIES

The other major sources of contemporary refugee flows in the Third World

are the conflicts associated with the formation of new political communities

out of the dismantled European colonial empires, mostly in Asia and Africa.

By and large, the successor states have adopted the nation as their model of

political organization; but the achievement of the objectives this entails is

extremely difficult because the ethnic and cultural heterogeneity of the

countries in question vastly exceeds that of the countries of Western Europe

where the model originated (Emerson, 1960; Geertz, 1973; Young, 1980).

This is partly a consequence of ancient historical processes resulting in a

complex ethnographic configuration; but it is attributable in part also to

imperial policies that had the effect of compounding differences between

ethnic and racial groups by endowing them with a dimension of social and

economic inequality (Zolberg, 1973; Hechter, 1975).

Nation-formation entails efforts to develop a common culture within a

country by reducing existing diversity. In relation to this broad objective,

the most relevant cultural elements are religion and language; but the

emphasis may extend to other forms as well, including ethnicity and "race"

(as defined within the relevant culture). In the classic Western European

cases, the process involved attempts by a politically dominant group which

defined its own culture as the "national" one to secure conformity to it by

others. In the face of non-compliance, authorities imposed conformity by

violent means, causing target groups to flee or to be expelled. The history of

state-formation in early modern Europe is punctuated by perennial flows of

?

religious refugees Jews and Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula (XVth,

XVIth, and XVIIth Centuries); Protestants from the southern Low Countries

(XVIth-XVIIth); Catholics, especially Irish, from the United Kingdom

(XVth-XVIIth); Protestants again from France before and after the Revocation

of the Edict of Nantes (1685), an event whose tricentenary was appropriately

commemorated by the refugee community last year (UNHCR, 1985). These

ground to a halt only in the XVIIIth century, after many of the minorities

had been eliminated (including by way of conversion) or silenced, and states

had begun to discover the material as well as moral benefits of tolerance.

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

162 International Migration Review

The contemporary situation of Third World countries was prefigured in

Eastern Europe and Western Asia following the dismantlement of the

Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires after World War I, when adoption

of the national model by highly heterogeneous successor states generated

enormous tensions, out of which emerged the minorities and the stateless,

"two victim groups... whose sufferings were different from those of all others

in the era between the wars", in that they "lost those rights which had been

thought of and even defined as inalienable, namely the Rights of Man"

(Arendt, 1973:268). As noted, the dismantlement was itself in part a con?

sequence of participation by those empires in a large-scale war; moreover,

throughout the area, tensions within each of the successor states were

compounded by further international conflicts, themselves fueled in part by

competing claims for the allegiance of national groups and their territorial

home, as well as by the ill treatment that neighboring states meted out to

what was a minority in one place, but the dominant nationality in the other.

The persecution of certain minorities on the ground that they constituted an

obstacle to the achievement of national unity even became a key mechanism

in the formation of a new type of regime among older nations that were not

significantly multiethnic (Arendt, 1973; Zolberg, 1983). These processes

produced new refugee flows from Europe and, when most of the states of

potential refuge barred entry to those persecuted, the Final Solution

(Marrus, 1985). It was largely out of this experience that the concept of

"refugees" entered into international law.

In Asia and Africa today, the intrinsic difficulties of nation-building are

compounded by underdevelopment; but this condition is itself deemed to

make consolidation of the nation-state especially urgent because rulers tend

to believe that only a strong state, founded on the sort of loyalty that national

solidarity fosters, can afford them the leverage necessary to pursue de?

velopmental objectives. It is noteworthy that these tendencies are independent

of the ideological orientation of the state in question. Since a given country's

ethnic groups always share unevenly in political and economic power to start

with ? for example, at the time of independence, for reasons indicated at the

beginning of this section ? nearly every type of social conflict between the

powerful and the weak, the haves and the have-nots, tends to manifest itself

also as a confrontation between ethnic groups.

In consequence, ethnic conflicts of all sorts are endemic throughout

contemporary Asia and Africa. Although they nearly always involve some

degree of violence, this is likely to be particularly high where ethnic (including

religious, racial, linguistic) differences clearly coincide with class lines.

Many former European colonies retain elements of this because they were

formed into "plural societies" by way of the establishment of a highly unequal

economic division of labor between specific groups of natives and immigrants

(Furmivall, 1948); elsewhere, such situations are attributable to a history of

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 163

by other non-Europeans. The advent of independence provides an op?

portunity for drastic action against privileged minorities, occasionally

producing large refugee movements. Leaving aside the departure of Euro?

peans, who as nationals or now "patrials" of the former imperial power

usually do not appear in the ranks of refugees, this can occur in a variety of

forms; by way of deliberate expulsion, as in the case of Ugandan Asians, or

attempted genocide with a massive exodus of survivors, as in Rwanda and

Burundi.

It is noteworthy, however, that most of the innumerable ethnic conflicts

involving violence in the regions under consideration do not produce refugee

flows. As in the case of revolutionary upheavals, the formation of refugee

flows is much more likely when the process of constituting a political

community is somehow internationalized. A prima facie case for this

proposition emerges from a consideration of two divergent patterns in the

Indian subcontinent: recurring ethnic conflict within India typically does

not produce refugees, but ethnic conflict within Pakistan, involving the

establishment of Bangladesh, produced millions of refugees within a few

months.

One distinctive pattern may be termed competitive nation-formation.

This occurs when the national model adopted is such that the objectives it

entails cannot be achieved except by violating the integrity of another state.

A first instance of competitive nation-formation is separatism, when an

ethnic minority ? usually concentrated within a particular territorial space

? which has been unable to secure

acceptable conditions within the state as

constituted seeks to establish a state of its own in defiance of the larger entity.

A second is irredentism, when a state seeks to incorporate under its jurisdiction

an ethnically cognate group that is presently under the jurisdiction of

another state; this usually involves conflict between the two states over the

territory inhabited by the group in question. The two processes sometimes

occur in complementary fashion within a given situation (e.g., Ogadeni

separatism within Ethiopia, and Somalian irredentism in relation to the

Ogaden).

However, changes of boundaries usually have more limited implications

for the distribution of power and values in the international system than

changes of regime* The internationalization of such conflicts is therefore

much more circumstantial, depending upon the location of the state or states

involved in relation to prevailing international alignments. Occasionally,

the large powers may become involved, as in the Horn of Africa; but more

typically, the issues are of concern primarily to regional actors. For example,

the conflict leading to the establishment of Bangladesh attracted only

superficial large-power attention, although it meant the breakup of an

existing country which was allied to the United States at the time; there was

also limited interest in the Biafran secession form Nigeria.

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

164 International Migration Review

Although conflict between governments and ethnic or religious minorities

is endemic throughout Asia and Africa, separatists are seldom successful.

Their victory appears to be conditional upon external support (Horowitz,

1981). At the very least, they will try to balance the inherent advantages of

the government forces which, by their very position, enjoy a measure of

external support in the form of diplomatic recognition, financial and legal

facilities for the acquisition of weapons, and the like (Modelski, 1964). But

whereas the diversity and competitive logic of the contemporary international

system make it possible for most movements to find an external patron of

some sort, the conservative nature of the system tends to limit that support to

a level short of what is required for success. As indicated, extra-regional

powers seldom have sufficient interest in the matter to warrant intervention;

and Third World neighbors usually hesitate to do so because of their residual

commitment to the maintenance of the boundaries they inherited, particularly

in Africa. A case in point is the adamant stance of the Organization of African

Unity on the issue of Eritrea. The major exception is Bangladesh, the only

case of successful separatism in the post-World War II period, attributable in

large part to India's intervention. Although that conflict generated a very

large flow of refugees, its outcome also provided a homeland to which the

refugees by and large returned within a short time.

The Bangladesh case suggests, more generally, that successful separatism

might be associated with a distinctive pattern of short-lived refugee move?

ment. However, unsuccessful separatist challenges also tend to produce

refugees, but of a more problematic kind. Despite their lack of success,

movements of this sort can persist for a long time because the state that is

challenged seldom possesses the resources required for effective repression

and containment, while the separatists ? by definition ? benefit from some

degree of popular support and have the advantage of operating on their own

terrain; as noted, they usually also manage to secure at least limited aid from

some patron. International assistance to the antagonistic camps has the effect

of enhancing their respective capacity, and hence to widen the firezone as

well as to prolong the conflict.

Separatism initially produces a small wave of political exiles, who have

little difficulty finding havens. If and when the struggle moves into a

military phase, a second and much larger wave emerges as entire populations

try to flee the fire zone and systematized repression. States facing separatist

guerillas typically exercise violence against the source group as a whole, any

member of which is considered an actual or potential supporter of insurgency.

Since we are speaking of a separatist movement which, by its very nature, is

likely to occur on the geographical periphery, near a state's international

borders, many in the target group usually succeed in getting out.

The UNHCR's expanded interpretation of its mandated role has helped

to reduce recognition problems refugees fleeing from the violence generated

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 165

by competitive state-formation and separatist conflict, as has the Organization

of African Unity's broad definition of refugees cited at the beginning of this

article. However, to the extent that neighboring states are opportunistically

involved in the conflict and face severe economic and political problems of

their own, the refugees find protection and support uncertain.

The impact of international factors is dramatically manifested in the case

of the Eritreans, whose protracted attempt to gain independence from

Ethiopia, compounded by occasional outbursts of internecine strife between

Christians and Muslims, has been going on for over twenty years, surviving

a revolutionary change in Ethiopia, which has given rise to refugee move?

ments of its own. The lasting power of the uprising and its many successes are

attributable not only to widespread opposition to annexation by Ethiopia,

but to external assistance from a broad array of Arab states ? whose conflicts

have contributed to the internal strife mentioned ?

including especially

Sudan, which has provided the rebels with adjoining external bases from

which to conduct operations. Until 1974, the Ethiopian imperial regime

contained the uprising with assistance from the United States and Israel; but

the protracted conflict contributed to its collapse in 1974 and the onset of

revolution. Taking advantage of these developments, four years later the

separatists were on the verge of success. However, massive intervention by

the Soviet Union and Cuba enabled Ethiopia's revolutionary government to

hang on to the major Eritrean cities, and then use them as bases for terror-

bombing the separatist-minded rural areas. The ups and downs of the

conflict over the last decade have generated several waves of refugees, whose

location in adjacent border regions within Sudan provides a manpower pool

for Eritrean military organizations.

REFUGEE-WARRIOR COMMUNITIES

Under appropriate circumstances, the internationalization of either of the

major types of social conflict considered can bring about a similar outcome,

the formation of a refugee-warrior community. This is well illustrated by the

otherwise disparate cases of Ethiopia and Afghanistan. The initial population

? Eritreans to the Sudan and ? involves

movement Afghans to Pakistan

whole societal segments, in which the men engaged in war are accompanied

by their dependents (and often animal flocks as well). In exile, however, they

usually lack the means for even subsistence production. Hence they are

heavily dependent on international or local assistance to stay alive. On

these grounds, they lay claim to and usually receive substantial human?

itarian relief. But communities of this type cannot persist for long unless

they secure substantial external partisan political support, because the

"warriors" are engaged in military operations across the border, and hence

associate their hosts in an act of war. Moreover, such communities frequently

receive material and diplomatic assistance from external patrons in re-

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

166 International Migration Review

cognition of their use as foreign policy instruments in related international

rivalries.

Once established, refugee-warrior communities tend to grow because they

provide opportunities and even incentives for others to become politically

active. Individuals in exile may find that the most socially meaningful and

economically rewarding activity is to join the warriors, and consequently

move from the category of mere displaced persons into that of the politically

active and conscious. These communities also seem to have radicalizing and

self-perpetuating dimensions. The refugee situation is one in which tra?

ditional leadership structures have been weakened, because their material

underpinnings have been removed; but it also offers a new set of resources in

a new situation which can be used by innovative political entrepreneurs to

establish themselves.

The contemporary archetype of the refugee-warrior community is con?

stituted by the Palestinians. While there are some important differences

between that case and the others mentioned, the more important point is that

each of them can be considered as a variant manifestation of a common type,

which might also include the Khmer on the Thai-Kampuchean border,

Nicaraguan "contras" operating out of Honduras and Costa Rica, and the

Western Saharan's POLISARIO with bases in Algeria and Mauritania. The

appearance of this phenomenon in many different parts of the Third World

suggests that refugee-warriors are perhaps the characteristic phenomenon of

our times.

Here as well as in the other situations considered, marginal economic

conditions tend to exacerbate the destructive impact of civil strife, and hence

have a multiplier effect on refugee flows. Concomitantly, continuous conflict

causes life-threatening economic dislocations in areas where the population

is already living close to subsistence level. As violence becomes a major

means of survival, it tends to feed on itself; this process may foster the

proliferation of armed factions, leading to the emergence of a warlord

system, as seems to have already occurred in Chad, and is perhaps under way

in Uganda as well.

CONCLUSIONS: POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The policy implications which flow from this analysis do not pertain to

immediate, operational questions of material assistance or asylum; rather,

they concern broader policy directions of relevance to all groups and agents,

public and private, that deal with refugees.

As other contributors to the "root-cause" debate correctly stress, to aid

those who at any given time happen to be refugees is a necessary but

insufficient response; to establish a basis for genuinely remedial policies, we

must achieve a better understanding of the reasons for the existence of

refugees (Sadruddin Aga Khan, 1981; Keely, 1981).

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 167

Refugees will continue to appear in the Third World because most of the

countries involved are in the throes of great social and political trans?

formations that unavoidably entail types of social conflicts that generate

violence, including classic persecution, and which people seek to escape by

fleeing, sometimes abroad. In this article, we have demonstrated that the

dynamics leading to the inception of these social conflicts are not purely

internal but transnational, and that as the conflicts develop they tend to be

further internationalized. This is the result of epochal trends that have

fostered a very general globalization of society and domestic politics.

The most extreme manifestation of this blurring of the boundaries between

what is internal and what is external to a given country is direct foreign

intervention, either in the form of troops, or of critical military and economic

assistance to one of the protagonists in a local confrontation. In the context of

a revolutionary conflict, either form of intervention tends to prolong and

exacerbate the conflict in such a way as to produce protracted and difficult

refugee situations. Less obvious, indirect forms of intervention (such as

economic and diplomatic embargos) have similar effects.8 In the context of

competitive nation-state formation, foreign intervention tends to have an

opportunistic character which also contributes to the making of severe,

festering refugee problems.

The countries presently engaged in such activities include the U.S, the

U.S.S.R., Vietnam, the Republic of South Africa, Libya, France, Cuba,

Israel, China, and Indonesia. As the list indicates, active interventionists

include both superpowers and smaller states, and states with a variety of

regime orientations. This would suggest that intervention is a general

structural propensity of the contemporary international system. But,

paradoxically, this also makes it possible to consider ways of changing the

situation. In this regard, we suggest the following guidelines for further

consideration.

1) The idea of solving the "global refugee crisis" by stepping up develop?

ment assistance to modify socioeconomic conditions in the countries of

origin is clearly insufficient. To the extent that the causes are international,

the solutions too require actions at the international level; in particular,

since refugee-producing situations are related to foreign intervention,

solutions require concerted diplomatic action.

2) From the specific perspective of the United States, this implies in the

first instance the necessity of modifying ongoing foreign policy. Americans

with a deep humanitarian concern for the plight of refugees must acknowledge

the necessity for action in this sphere, not as an afterthought but as a central

concern.

8 The current argument that sees U.S. intervention in Central.America as a means to

prevent

future flows of "feet people" posits a complete inversion of this historical dynamic. A recent

succinct discussion of this can be found in Gomez (1984).

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 International Migration Review

3) The general direction of policy modification must be towards reduced

intervention. As in the case of arms control, which is a useful analogy,

reduced intervention can be achieved by various procedures. Unilateral

restraint is appropriate at certain times; other situations call for negotiations

to promote mutual regulation. Although the vision of an end to all inter?

vention is Utopian, and perhaps even morally dubious, this does not mean

that it is impossible to make progress toward restraining intervention so as to

alleviate human suffering.9

4) It must be recognized that refugee policy cannot be "humanitarian" in

the sense of completely apolitical. decision as to whether or not to

The

support various groups as "refugees" always implies to some degree a foreign

policy decision. Conscious deception of others, or unconscious deception of

self, can be reduced by seeking to make the recognition explicit. This applies

to government agencies as well as voluntary agencies and public interest

groups.

9 A legal and moral argument can be made for intervention in certain cases, notably those

involving massive and gross violations of human rights. Stanley Hoffman (1981)presents a recent

liberal formulation of this view.

REFERENCES

Arendt, H.

1973 The Originsof Totalitarianism.

Rev. ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch.

Barraclough, G.

1967 Introductionto ContemporaryHistory.Harmondsworth: Pelican.

Bull, H. and A. Watson (eds).

1984 The Expansionof InternationalSociety.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freund, B.

1984 The Makingof Contemporary

Africa.Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Furmivall, J.S.

1948 ColonialPolicy and Practice.London: Cambridge University Press.

Gomez, L.

1984 "Feet People". In CentralAmerica:Anatomyof a Crisis.Edited by Robert Leiken. London:

Pergamon Press. Pp. 219-299.

Goodwin-Gill, G.

1983 The Refugeein InternationalLaw.Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hechter, M.

1975 InternalColonialism.Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hoffman, S.

1981 Duties Beyond Borders.Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Horowitz, D.

1981 "Patterns of Ethnic Separatism", ComparativeStudiesin Societyand History,23:165-195.

Keely, C.

1981 Global Refugee Policy: The Case for a Development-OrientedStrategy.New York: The

Population Council.

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International Factors in the Formation of Refugee Movements 169

Keohane, R. and J. Nye (eds.)

1972 Transnational Relationsand WorldPolitics.Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Markakis, J. and N. Ayele

1978 Classand Revolutionin Ethiopia.Nottingham: Spokesman.

Marrus, M.

1985 The UnwantedEuropeanRefugeesin the TwentiethCentury.New York: Oxford University

Press.

Modelski, G.

1964 "The International Relations of Internal War". In InternationalAspects of Civil Strife.

Edited by James N. Rosenau. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

National Security Council

1953 "Psychological Value of Escapees from the Soviet Orbit", Security Memorandum, March

26 (typewritten, 4pp.)

Paige, J.

1975 AgrarianRevolution.New York: Free Press.

Skocpol, T.

1979 Statesand SocialRevolutions.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Suhrke, A.

1983 "Global Refugee Movements and Strategies of Response". In U.S.ImmigrationandRefugee

Policy:Globaland DomesticIssues.Edited by M. Kritz. Lexington: D.C. Heath.

Suhrke, A. and A. Zolberg

1984 "Social Conflict and Refugees in the Third World: The Cases of Ethiopia and Afghan?

istan". Paper presented at the Center for Population Studies, Harvard University.

United Nations Economic and Social Council

1981 "Study on Human Rights and Massive Exoduses" (Sadruddin Aga Khan, rapporteur),

December 31.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees

1985 Refugees(September). Pp. 17-33.

Wallerstein, I.

1979 The CapitalistWorld-Economy.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

New York: Academic Press.

1974 The Modern World-System.

Wyman, D.

1984 The Abandonmentof theJews.New York: Pantheon.

Zolberg, A.

1983a "The Formation of New States as a Refugee-Generating Process". In The GlobalRefugee

Problem:U.S.and WorldResponse,TheAnnalsof theAmericanAcademyof Politicaland Social

Science,467:24-38. Edited by G. Loescher and J. Scanlan.

1983b " 'World'and 'System':A Misalliance". In ContendingApproachesto WorldSystemAnalysis.

Edited by W.R. Thompson. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 269-290.

1981 "International Migrations in Political Perspective". In Global Trends in Migration:

Theory and Research on InternationalPopulation Movements. Edited by M. Kritz, C.

Keely, and S.M. Tomasi. New York: Center for Migration Studies.

1973 "Tribalism Through Corrective Lenses", ForeignAffairs,51:728-739.

1967 "The Structure of Political Conflict in the New States of Tropical Africa", American

PoliticalScienceReview,52:70-87.

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 08:14:07 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Escape From ViolenceDocument395 pagesEscape From Violencealexis melendezNo ratings yet

- Immigration and Integration in Israel and BeyondFrom EverandImmigration and Integration in Israel and BeyondOshrat HochmanNo ratings yet

- Aristide R. Zolberg, Astri Suhrke, Sergio Aguayo - Escape From Violence - Conflict and The Refugee Crisis in The Developing World-Oxford University Press (1989)Document395 pagesAristide R. Zolberg, Astri Suhrke, Sergio Aguayo - Escape From Violence - Conflict and The Refugee Crisis in The Developing World-Oxford University Press (1989)Coca LoloNo ratings yet

- Todo TodoDocument28 pagesTodo TodoRafa CuencaNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Human Rights: A Global PerspectiveFrom EverandThe Politics of Human Rights: A Global PerspectiveRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Technologies of Suspicion and the Ethics of Obligation in Political AsylumFrom EverandTechnologies of Suspicion and the Ethics of Obligation in Political AsylumBridget M. HaasNo ratings yet

- Abject CosmopolitanismDocument26 pagesAbject CosmopolitanismGianlluca SimiNo ratings yet

- Less Than a Human: The Politics of Legal Protection of Migrants with Irregular StatusFrom EverandLess Than a Human: The Politics of Legal Protection of Migrants with Irregular StatusNo ratings yet

- 0.03%!: Let’s transform the international humanitarian movementFrom Everand0.03%!: Let’s transform the international humanitarian movementNo ratings yet

- Amanda Ekey, Refugees and Terorrism, NYUDocument37 pagesAmanda Ekey, Refugees and Terorrism, NYUismail shaikNo ratings yet

- REFUGEE LAW-REBECCA HAMLIN The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law-Oxford University Press, USA (2021) - 199-210Document12 pagesREFUGEE LAW-REBECCA HAMLIN The Oxford Handbook of International Refugee Law-Oxford University Press, USA (2021) - 199-210Badhon DolaNo ratings yet

- Immigration Control in a Warming World: Realizing the Moral Challenges of Climate MigrationFrom EverandImmigration Control in a Warming World: Realizing the Moral Challenges of Climate MigrationNo ratings yet

- New Games For OntologyDocument26 pagesNew Games For OntologyCarlos Augusto AfonsoNo ratings yet

- PionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991Document25 pagesPionBerlin VictimsExecutionersArgentine 1991caitlinsarah12342No ratings yet

- Internally Displaced PersonDocument14 pagesInternally Displaced PersonNamrah AroojNo ratings yet

- Security, Culture and Human Rights in the Middle East and South AsiaFrom EverandSecurity, Culture and Human Rights in the Middle East and South AsiaNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Humanitarianism and The Erosion of Refugee ProtectionDocument21 pagesGlobalization, Humanitarianism and The Erosion of Refugee ProtectionCarolina MatosNo ratings yet

- MigrationDocument9 pagesMigrationkehinde uthmanNo ratings yet

- Refugees: Risks and Challenges WorldwideDocument11 pagesRefugees: Risks and Challenges WorldwideIrfan AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Mass Migration As A Hybrid Threat - A Legal PerspeDocument29 pagesMass Migration As A Hybrid Threat - A Legal PerspeMMR TravelNo ratings yet

- SUICIDE TERRORISM: IT'S ONLY A MATTER OF WHEN AND HOW WELL PREPARED ARE AMERICA'S LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERSFrom EverandSUICIDE TERRORISM: IT'S ONLY A MATTER OF WHEN AND HOW WELL PREPARED ARE AMERICA'S LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERSNo ratings yet

- Political Life Beyond Accommodation and ReturnDocument21 pagesPolitical Life Beyond Accommodation and ReturnVinícius SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Theories About International Law Prologue To A Configurative JurisprudenceDocument112 pagesTheories About International Law Prologue To A Configurative Jurisprudencesanjeev k soinNo ratings yet

- American Sanctions Against The Soviet Union From Nixon To ReaganFrom EverandAmerican Sanctions Against The Soviet Union From Nixon To ReaganNo ratings yet

- Brand NationalNarrativesMigration 2010Document34 pagesBrand NationalNarrativesMigration 2010Elie DibNo ratings yet

- 2016 UnhcrstudyguideDocument12 pages2016 Unhcrstudyguideapi-247832675No ratings yet

- Externalisation, Access To Territorial Asylum, and International LawDocument37 pagesExternalisation, Access To Territorial Asylum, and International LawMellissa KNo ratings yet

- University of Petroleum and Energy Studies: Human Rights Project Project Topic - Refugee RightsDocument18 pagesUniversity of Petroleum and Energy Studies: Human Rights Project Project Topic - Refugee RightsHärîsh Kûmär100% (1)

- Making International Refugee Law Relevant Again - A Proposal For C PDFDocument98 pagesMaking International Refugee Law Relevant Again - A Proposal For C PDFIntisarNo ratings yet

- IJRHAL - Refugees and Human Security-A Study of The Rohingya Refugee CrisisDocument8 pagesIJRHAL - Refugees and Human Security-A Study of The Rohingya Refugee CrisisImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Ihl Project - 07b150Document19 pagesIhl Project - 07b150xyzvinayNo ratings yet

- 1564050365.9206dealing With The Refugee Crisis With Emphasis On Amending The Convention Relating To The Status of Refugees PDFDocument10 pages1564050365.9206dealing With The Refugee Crisis With Emphasis On Amending The Convention Relating To The Status of Refugees PDFSuji SujiNo ratings yet

- Essay On Regime Theory and Social Constructivist Theory & HumanitrianismDocument11 pagesEssay On Regime Theory and Social Constructivist Theory & HumanitrianismJihad TahaNo ratings yet

- Stanford Law Review: Migration As DecolonizationDocument66 pagesStanford Law Review: Migration As DecolonizationLivia StaicuNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian Intervention Conceptual AnaDocument29 pagesHumanitarian Intervention Conceptual AnaHiếu Ninh Thế HuyNo ratings yet

- The Birth of A Discipline': From Refugee To Forced Migration StudiesDocument19 pagesThe Birth of A Discipline': From Refugee To Forced Migration StudiesANo ratings yet

- Is Migration A Security IssueDocument17 pagesIs Migration A Security Issuejaseme7579No ratings yet

- Vulnerability: Governing the social through security politicsFrom EverandVulnerability: Governing the social through security politicsNo ratings yet

- Examining The Concept of Refugeehood and Critically Discussing PDFDocument11 pagesExamining The Concept of Refugeehood and Critically Discussing PDFsevenNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Law ProjectDocument25 pagesHuman Rights Law ProjectShivanshu PuhanNo ratings yet

- Activists and the Surveillance State: Learning from RepressionFrom EverandActivists and the Surveillance State: Learning from RepressionNo ratings yet

- Border abolitionism: Migrants’ containment and the genealogies of struggles and rescueFrom EverandBorder abolitionism: Migrants’ containment and the genealogies of struggles and rescueNo ratings yet

- Trouillot Michel-Rolph - 2001 - The Anthropology of The State in The Age of GlobalizationDocument15 pagesTrouillot Michel-Rolph - 2001 - The Anthropology of The State in The Age of GlobalizationAlex AndriesNo ratings yet

- Trouillot 2001Document15 pagesTrouillot 2001luluskaaNo ratings yet

- Illegal Immigration, Human Trafficking and Organized CrimeDocument27 pagesIllegal Immigration, Human Trafficking and Organized CrimeSyuNo ratings yet

- Internationa SystemDocument15 pagesInternationa SystemElene MikanadzeNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper On Who Is A Refugee by ShacknoveDocument7 pagesReflection Paper On Who Is A Refugee by ShacknoveziamqNo ratings yet

- Research Paper SyriaDocument10 pagesResearch Paper Syriasvfziasif100% (1)

- Global Cooperation Efforts On Migration1Document3 pagesGlobal Cooperation Efforts On Migration1boniface ndunguNo ratings yet

- Landscapes of Law: Practicing Sovereignty in Transnational TerrainFrom EverandLandscapes of Law: Practicing Sovereignty in Transnational TerrainNo ratings yet

- Refugees and IdpsDocument9 pagesRefugees and IdpsMAGOMU DAN DAVIDNo ratings yet

- SV - 1Document19 pagesSV - 1Hina OdaNo ratings yet

- The Enemy at The Gates: International Borders, Migration and Human RightsDocument18 pagesThe Enemy at The Gates: International Borders, Migration and Human RightsTatia LomtadzeNo ratings yet

- PanelDocument16 pagesPanelMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- Bjgpjul 2015 65 636 376Document2 pagesBjgpjul 2015 65 636 376Marie DupontNo ratings yet

- Everett 2003Document6 pagesEverett 2003Marie DupontNo ratings yet

- RRN Research Digest No. 88Document4 pagesRRN Research Digest No. 88Marie DupontNo ratings yet

- Political Economy of Economic Policy Jeff FriedenDocument6 pagesPolitical Economy of Economic Policy Jeff FriedenMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- Contextual Orientation in Policy Analysis The Contribution of Harold D. LasswellDocument21 pagesContextual Orientation in Policy Analysis The Contribution of Harold D. LasswellMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- International Migration Trends in Latin America - Research and Data SurveyDocument21 pagesInternational Migration Trends in Latin America - Research and Data SurveyMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- CDMG 2006 11e Final Report MG-R-PE enDocument50 pagesCDMG 2006 11e Final Report MG-R-PE enMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- Foundational Works in Public Policy Studies Harold D. LasswellDocument4 pagesFoundational Works in Public Policy Studies Harold D. LasswellMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- International Migrations To Brazil in The 21st CenturyDocument35 pagesInternational Migrations To Brazil in The 21st CenturyMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- Migration Theory: Handbook of The Economics of Interna-Tional MigrationDocument13 pagesMigration Theory: Handbook of The Economics of Interna-Tional MigrationMarie DupontNo ratings yet

- Potassium Permanganate CARUSOL CarusCoDocument9 pagesPotassium Permanganate CARUSOL CarusColiebofreakNo ratings yet

- Bulletin - February 12, 2012Document14 pagesBulletin - February 12, 2012ppranckeNo ratings yet

- Cpa f1.1 - Business Mathematics & Quantitative Methods - Study ManualDocument573 pagesCpa f1.1 - Business Mathematics & Quantitative Methods - Study ManualMarcellin MarcaNo ratings yet

- AA-SM-010 Stress Due To Interference Fit Bushing Installation - Rev BDocument3 pagesAA-SM-010 Stress Due To Interference Fit Bushing Installation - Rev BMaicon PiontcoskiNo ratings yet

- Revised LabDocument18 pagesRevised LabAbu AyemanNo ratings yet

- FORM Module IpsDocument10 pagesFORM Module IpsRizalNo ratings yet

- MINDSET 1 EXERCISES TEST 1 Pendientes 1º Bach VOCABULARY AND GRAMMARDocument7 pagesMINDSET 1 EXERCISES TEST 1 Pendientes 1º Bach VOCABULARY AND GRAMMARanaNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity No.2Document1 pageLearning Activity No.2Miki AntonNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Learning Competency/iesDocument1 pageDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) Format: Learning Competency/iesErma JalemNo ratings yet

- UVEX - Helmets & Eyewear 2009Document19 pagesUVEX - Helmets & Eyewear 2009Ivica1977No ratings yet

- Case Study 17 TomDocument7 pagesCase Study 17 Tomapi-519148723No ratings yet

- Charging Station For E-Vehicle Using Solar With IOTDocument6 pagesCharging Station For E-Vehicle Using Solar With IOTjakeNo ratings yet

- 2 MercaptoEthanolDocument8 pages2 MercaptoEthanolMuhamad ZakyNo ratings yet

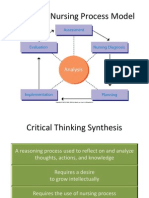

- NUR 104 Nursing Process MY NOTESDocument77 pagesNUR 104 Nursing Process MY NOTESmeanne073100% (1)

- Solutions For Tutorial Exercises Association Rule Mining.: Exercise 1. AprioriDocument5 pagesSolutions For Tutorial Exercises Association Rule Mining.: Exercise 1. AprioriMarkib Singh AdawitahkNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Unstable or Astatic Gravimeters and Marine Gravity SurveyDocument9 pagesAssignment On Unstable or Astatic Gravimeters and Marine Gravity Surveyraian islam100% (1)

- TML IML DefinitionDocument2 pagesTML IML DefinitionFicticious UserNo ratings yet

- IAU Logbook Core 6weeksDocument7 pagesIAU Logbook Core 6weeksbajariaaNo ratings yet

- Po 4458 240111329Document6 pagesPo 4458 240111329omanu79No ratings yet

- English Lesson Plan Form 4 (Literature: "The Living Photograph")Document2 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan Form 4 (Literature: "The Living Photograph")Maisarah Mohamad100% (3)

- Module 11 Activity Based CostingDocument13 pagesModule 11 Activity Based CostingMarjorie NepomucenoNo ratings yet