Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Music and Narrative in Five Films by Ousmane Sembène

Uploaded by

Amsalu G. TsigeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Music and Narrative in Five Films by Ousmane Sembène

Uploaded by

Amsalu G. TsigeCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of African Cinemas Volume 1 Number 2 © 2009 Intellect Ltd

Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jac.1.2.207/1

Music and narrative in five films by

Ousmane Sembène

Samba Diop The Institute of Cultural Studies and Oriental

Languages, University of Oslo, Norway

Abstract Keywords

Diop’s article focuses on music in Ousmane Sembène’s films as an integral part of Sembène

film narrative. The author first describes the traditional instruments of Senegal music

and their usage, and proceeds to analysing the mood they create in Sembène’s first sound

three socio-realist films (Borom sarret, La noire de…/Black Girl, Mandabi). environment

As a narrative counterpoint to traditional instruments, piano dance music mostly narrative

indicts the colonial ideology and its aftermath after independence. This study also

illustrates Sembène’s well-known concern for egalitarianism among the vari-

ous ethnic groups of Senegal. Diop extends his study to Sembène’s changing and

experimental concept of sound as a narrative device. He analyses the meaning of

vocals (with their translation), the sounds of the environment as well as silence in

Emitaï; and in Sembène’s more recent films, he interprets the use of popular stars

heard over the radio as a sign of the democratization of the enjoyment of music.

Introduction

As Francis Bebey (1975: 119) has correctly observed, ‘African music is

based on speech. The bond between language and music is very intimate.’

Speech itself is intimately linked to oratorical art and, in the process of

making his films, Sembène is aware that the Senegalese people whose

experience he wants to render are mostly illiterate in European languages.

Therefore, the indigenous customs and world-view are couched inherently

in African orality. Sada Niang (1996: 59) noted that Ousmane Sembène is

generally aware of ‘the repressive and restrictive nature of writing and

written texts’ and Imruh Bakari (2000: 9) observed that Sembène is con-

cerned with ‘the articulation of African subjectivity inside/outside of

modernity’. Thus, in most of his films, Sembène takes great care to render

the prevailing oral culture in Senegalese society.

The presence of music in Sembène’s films is varied and has many pur-

poses. Sembène judiciously uses the different tones of music and words as

forms of writing but also as ways of expressing an opinion or just getting

his point across. Thus, I will analyse the multifaceted dimension of music

in a selection of Sembène’s films while taking into account the time span

of about forty years that the films cover, starting with Borom sarret/

Bonhomme charrette/The Cart Driver (1963) and ending with Faat Kine

(2001). The aforementioned time span is just a yardstick that measures

the film-maker’s growth, coming of age as well as his itinerary. It will be

JAC 1 (2) pp. 207–224 © Intellect Ltd 2009 207

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 207 1/13/10 2:19:14 PM

apparent that over the years, the film-maker’s theme-related concerns

have changed but not his sharp eye and critical observation of Senegalese

society. What has remained constant, however, is Sembène’s artful play

and mixing of seemingly disparate and disjointed themes. He appeals to

music in order to fill the void created by the unsatisfactory and incomplete

nature of graphic writing. The film-maker strives to find alternatives to

traditional writing and what better choice of communication and expres-

sion than music.

Before discussing the many facets of music and words in Sembène’s

films, it is important to specify that within the scope of this article, music

should be understood as an encompassing concept that goes beyond the

mere playing of musical instruments; voice and the elements of nature also

constitute musical forms. Soundtrack plays a central role in Sembène’s

films and renders his concerns imperious and compelling. One senses

urgency on the part of the film-maker as he attempts to chronicle the

present, the conditions of living in present-day postcolonial Africa. It is also

fair to say that Sembène is not overly concerned with a mythical and vain-

glorious African past even though he treats the historical past in some of

his films such as Ceddo (1976) and Camp de Thiaroye (1988). However, even

in the aforementioned films, the African past as a theme is not front and

centre; rather, Sembène wants to bring forth the idea of a usable past, in

other words, to use the past in order to shed light on the present. Gugler

(2003: 8) rightly remarks that the quest for authenticity and the usage of

amateur actors make an African language such as Wolof the language of

choice in Sembène’s films. Indeed, finding refuge in a useless past for the

sake of it does not appeal to Sembène. ‘Music of the present time’, an expres-

sion borrowed from Michel Chion (1995: 291), succinctly renders

Sembène’s concerns and, to that end, the music in his films takes the form

of a polyrhythm, a polyphony, that is an integrated whole of the various

types of rhythms and of musical forms, traditional as well as modern ones.

Thus, the Senegalese film-maker sets a goal of translating and of render-

ing the various ethnic identities that compose the tapestry of his country.

He tries to do so without falling into the ethnocentric ethos or into an excess

of ethnic praise. It is a balancing exercise as the film-maker tries to show the

rich and diverse indigenous cultures and languages without putting any

one of them above the others: Sembène strives for egalitarianism among the

various ethnic groups of Senegal. As a pan-Africanist, the film-maker is

careful not to over-emphasize ethnic identity, which can be divisive and

tribal (to the detriment of a more holistic national and pan-African identity

that will supersede an atomized and fragmented tribal identity). In the final

analysis, music and soundtrack as obtained from the Senegalese ethnic

groups must be appreciated under the angle of variety and the need to dem-

onstrate that Africans have rich cultures. This consideration must not pre-

clude (as pointed out earlier) a more encompassing national and wholesome

African identity within which all ethnic groups can fit; in other words,

Sembène tries to make the whole the sum of its parts.

A short explanation of the musical instruments used in the films being

discussed in this essay will illustrate the cultural context from which

Sembène draws his musical inspiration. In general, the instruments follow

the ethnic lines; for instance the Wolof drum also known as sabar is

208 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 208 1/13/10 2:19:14 PM

prominent in Mandabi/Le Mandat/The Money Order (1968), the sound com-

ing from the sabar is sharp and light and generally denotes a festive atmos-

phere or a party. As the opposite of the sabar, we have the Diola drum,

which is the symbol of a forest culture, that of the Diola people. In Emitaï

(1972), a film that takes place in Casamance, the drum is not at all joyful

but rather heavy and always signals the presence of danger. In scenes in

which the sound travels over and across the trees, the drum warns the

various groups disseminated across the forest of the invasion of the vil-

lages by the soldiers of the French colonial army. In addition, the military

drum (tambour), an obvious import from France whose beat accompanies

the soldiers’ steps, denotes order, discipline, determination, esprit de corps

but, above all else, the will to kill as soldiers are trained for that purpose.

Concerning the string instruments, two types are mostly used in

Sembène’s films: first, we have the Wolof xalam, a three-stringed instru-

ment (there is also a four-stringed version) that is present in Borom sarret

and is often accompanied with songs. Then we have the kora, the

21-stringed instrument with a hollow calabash at the bottom of the instru-

ment. Unlike the Wolof sabar and the Diola drum, the kora is not linked to

any particular ethnic group in Sembène’s films even though the instru-

ment originates from Mande culture. The kora is used in many scenes that

describe general African culture and customs, those found in almost all

ethnic groups; thus, the kora can be considered as a unifying musical

instrument as it provides a bridge that links the various ethnic groups of

Senegal. Altogether, Sembène faces a triple challenge. Indeed, how can

the artist appeal to African traditional narrative and aesthetic forms while

blending the latter with the image and then infuse it with both music and

soundtrack in order to strike a balance? Or, as articulated by Thackway

(2003: 11), how to ‘develop the narrative and aesthetic pleasure of film

[and] explore traditional narrative forms [and] focus more on the quality

of the images themselves’? Obviously, Sembène is proud of the multicul-

tural and multilingual fabric of Senegalese society and likes to promote

African art and its specificity. I will attempt to show how the Senegalese

film-maker faces this challenge.

Sembène assigns aesthetic qualities to each musical instrument. In

effect, if each instrument is linked to a specific ethnic group – as that will

be apparent later in my analyses – it remains that Sembène puts more

emphasis on cultural differences per se, rather than on ethnocentric val-

ues as it were. Actually, throughout his life and work (creative writing

and films), the film-maker has strived to downplay ethnocentrism and has,

instead, celebrated values such as pan-African solidarity. Again, this does

not mean that ethnicity is not important in Sembène’s work. Ethnicity in

Africa is a reality that cannot be denied. Thus, Sembène thought it more

judicious to focus on culture. To that end, the aesthetic qualities and

attributes of the instruments are tied to the various cultures as represented

in the films that I will discuss below. As examples, the drum (sabar) is tied

to Wolof culture; that musical instrument emits sharp notes and the

accompanying dance compels the dancer to be nimble and to jump in the

air as often as dictated by the rhythm. Thus, a vertical type of dance. In

contrast, the Diola drum emits heavy sounds; in this stance, and contrary

to the Wolof dancer, the Diola dancer drags his feet and keeps them on the

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 209

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 209 1/13/10 2:19:14 PM

floor, thus the dance is grounded on the floor if I may put it that way. We

are here in the presence of a horizontal type of dance. Finally, the last

musical element, the kora, has strings just like the guitar and does not

involve any dance (contrary to the drums); rather, the kora puts the lis-

tener in a pensive, joyous, elated or sad mood.

Borom sarret

In Borom sarret, at the very beginning of the film one hears the call to

Islamic prayer by the muezzin for the dawn prayer, the first Muslim prayer

of the day. The call signals the start of the day’s activities, in the same way

as a cock crowing or an alarm clock. The choice of starting the film with

the call to prayer is not accidental, for the cart driver (who is the main

character of the film) is Muslim and prays before setting off for work.

Furthermore, the call of the muezzin is a singing voice that fulfils an

important function: to draw the attention of the believers to their daily

religious duties. As in most of his films, Sembène creates a dichotomy

along the lines of tradition and modernity; the traditional themes are

accompanied by the playing of the xalam whereas when the film-maker

comes across modernity, he uses European classical music. In effect,

starting with Borom sarret (as well as in most of his films), the European

colonial experience in Africa is overwhelming.

The narrative plot of Borom sarret closely follows the dichotomy noted

earlier. Like many African cities, Dakar (where this was shot) is a colonial

city that traditionally features the European quarter on the one hand and

the indigenous native neighbourhood on the other, in the layout that is

present in many novels by African writers such as Mongo Beti, Ahmadou

Kourouma and Bernard Dadie. The European city is clean, the streets are

paved and lined with trees; the buildings and dwellings are freshly painted

in white, the lawns are well kept and the flower beds manicured; in short,

the European city is synonymous with cleanliness, order, education and a

new and modern way of seeing the world. In contrast, in addition to the

trash that is never collected, the native quarter is dirty, the streets are

unpaved and full of sand and the houses are usually wooden and tin

shacks. The native quarter is the very expression of poverty and is the

shanty town inhabited by the disenfranchised, the poor, the marginalized

and all the villagers who migrated in droves to the city in search of greener

pastures. This geographical dichotomy is still in existence in postcolonial

Africa. Thus, in his acerbic satire of the African postcolonial elites, Sembène

rightly shows that the new black African elites who replaced the white

colonizers now inhabit the beautiful dwellings and apartments left behind

by the departed European colonizers. These new elites are not concerned

with developing their country. Their goal is to have fun and being inde-

pendent for them means to party, not to work.

Thus, music in Borom sarret highlights class division and temporal

realities. The xalam is the symbol of the African past, of the kingdoms of

yesteryear. In one episode, a griot publicly sings the ancestors of the cart

driver who shares the same first name as Sembène: Ousmane. This might

be for Sembène, whose leftist and Marxist beliefs are well known, a way of

identifying with the working class. While enumerating an obviously fake

genealogy, the sound of the xalam accompanies the voice of the bard.

210 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 210 1/13/10 2:19:14 PM

Ousmane, the cart driver is happy and thinks that he too is entitled to

praises, in spite of his inferior social and economic position. Despite his

misery, he is still a noble albeit a poor one. In this episode, Sembène uses

lyrics and music as a means of economic exchange, for upon singing the

cart driver’s praise, the griot receives in return some money as a reward.

Music also soothes the pain of the poor city dweller as this is the only

instance when Ousmane smiles. Normally, he toils in order to eke out a

living in the city. This praise scene deserves commentary.

We are in the presence of a public performance which takes place in

the street as, while the griot is singing, there is a crowd watching and lis-

tening. Beforehand, however, Ousmane asked questions, in an internal

monologue: ‘Who is singing about my ancestors, the brave warriors of the

past? Their blood flows in my veins. Even if this new life enslaves me, I am

still noble like my ancestors.’ Straight after this monologue, the griot enters

into action and starts singing the cart driver’s praise. The translation of

the lyrical composition of the griot from Wolof into English is mine:

I greet you Ousmane Dieng

The traditions

I am going to entertain you today about the traditions

Ousmane Dieng

I am going to praise you

Nguirane is his father

Coumbe the noble one Macoro Faye

Majojo Penda and

Mame Samba Jimak Ndiaye

Who stays in Ciloor

Mojojo Ndiaye Sigèer Kane

Birame Ndjèmé Coumba

They are the disciples of Serigne Guèye in Touba

Birame Ndjèmé Coumba.

The song sounds like a fake genealogy. The singer has fabricated a geneal-

ogy for Ousmane Dieng, and in return, he receives his due. There is an

expectation on the part of the performer. Most of the singer’s performance

is made of a concatenation of names which are supposed to be the cart

driver’s ancestors, brave ones just as Ousmane would have wished for in

his monologue. Furthermore, at the beginning of his praise, the griot

inflates the man’s ego and succeeds. Ousmane is very happy and pays the

griot twice. The griot has hit his mark, which consists of flattering the per-

son in order to receive a reward. Clearly, the relationship between the griot

and the cart driver is based on an economic exchange. The situation of the

griot here is emblematic of the role and function of any griot in modern

Senegalese society. Sembène wants to show that the griot has become

irrelevant and obsolete. In the heydays of African kingdoms and empires,

the griot played a vital and needed role. Now, he has become a parasite,

surviving in the city for his only skills are his voice and his adroitness at

flattering people. One must also appreciate the griot’s improvisational skills

that, in turn, are the hallmark of oral cultures. The very fact that, although

he has never met Ousmane before, he is able to create a genealogy for him

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 211

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 211 1/13/10 2:19:15 PM

on the spot is proof that he is good at his craft. As the saying goes, ‘neces-

sity is the mother of invention’.

In Borom sarret, Sembène creates a movement built around the mobil-

ity of the cart driver who goes around with his cart and horse in order to

seek out people and goods to transport. Thus, early in the day, he trans-

ports people on their way to work; after that, he carries cement blocks;

then a pregnant woman who is about to give birth; after that, a father

asks him to help him take the body of his deceased infant child to the cem-

etery for burial. However, the episode that really highlights the epic move-

ment of the film is when a westernized African man, dressed in European

clothes, wants to go into the European quarter in order to carry some

goods. At first, Ousmane refuses, and rightly so, as the city centre is forbid-

den to horses and carts. After much insistence on the part of the western-

ized customer, he finally gives in. His fears are realized as a police officer

stops him and confiscates the cart; to add insult to injury, the vile cus-

tomer does not pay the poor cart driver. Ousmane returns to the native

quarter with his horse in tow. The discreet sound of an orchestral version

of Mozart’s Ave Verum rises as the camera shows the skyline with the

tops of the buildings occupying the whole space. However, throughout

his return walk, Ousmane’s monologue against ‘modern life’ covers

Mozart’s music. As he reaches his neighbourhood (quartier populaire), he

seems elated, free and happy to be back on familiar ground. At that

moment, the music of the xalam is heard again.

Borom sarret is a tale of marginalization in which Sembène uses music

as a trope that delineates class division. Within the frame of the city, class

separations are very sharp as the rich and educated live in a sanitized and

closely guarded world whereas the poor inhabit the slums at the periphery

and margin of the city. To each its music: to the native quarter the sound

of the xalam whereas the European quarter is represented by classical

music. Again, towards the end of the film, a shot shows the receding sky-

line of the city centre while the moving camera simultaneously brings to

the fore the shacks of the native quarter, an almost prospective glimpse of

what lies ahead, poverty and wretchedness. All the same, Sembène vividly

captures the class reality of the new postcolonial Africa, a new dawn that

is not at all promising.

La Noire de... /Black Girl

The next film, La noire de…/Black Girl (1966) is articulated around the

tragic end of a maid called Diouana who dies in France where she was

brought by her white French employers. They normally reside and work

in Senegal; however, while vacationing in southern France, they bring

Diouana along with them and the maid will encounter her demise. The

plot of the film as well as the main narrative line can be read through the

mask. Paulin Vieyra (1972: 75) notes that the mask is at first a sign of

friendship between Diouana and her female employer, then becomes an

element of discord once they are all in France and at the end it is the sym-

bol for Africa. An omnipresent object and work of art, the mask also

reveals the various musical modalities. The mask is primarily an art object

that Diouana gave to the couple as a present. They put it on the wall of

the apartment as decoration. When they left for France, the couple took

212 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 212 1/13/10 2:19:15 PM

the mask along with them, but as the relationship between the woman

and her employers soured, the mask became a bad omen. In the scene

when Diouana asks the couple to give her the mask back, the French wife

refuses; however, the husband tells her to give it back to Diouana as it

belongs to her. The wife is obsessed with the mask. Is it because of remorse

for having badly treated the maid? After Diouana’s suicide, the last modal-

ity as played by the mask is at the end of the film when the Frenchman

returns the mask to Diouana’s family, along with her belongings. The

family lives in a slum at the periphery of the city of Dakar. In this scene, a

child puts the mask on his face and tries to scare the Frenchman. The

Frenchman leaves Diouana’s family compound in brisk steps as if he

were scared, revealing his foreignness and guilt, perhaps. In other words,

the Frenchman is out of place. His real abode is the European quarter and

he must return to where he belongs, as he is obviously unwanted in the

native neighbourhood.

I want to show that contrasting musical instruments intimately

relate to the changing functions of the mask in the narrative. Black Girl

is replete with different musical instruments, each delineating a precise

narrative function in addition to featuring a cultural reality. At the

beginning of the film, a liner (Ancerville, the name of the boat, has actu-

ally existed from the 1950s to the late 1970s plying the maritime route

between Marseilles and Dakar via Casablanca) is shown entering the

port of Marseilles, with Diouana on board. As soon as she gets off the

boat, she is met by her boss (called ‘Misse’, an obvious mispronuncia-

tion of ‘Monsieur’). Then, after having put Diouana’s suitcase in the

trunk of the car, they set off. They drive on the famous Côte d’Azur

accompanied by boisterous chords played on the sort of out-of-tune

pianos used in popular dance halls (pianos bastringues). The music may

come from a pianola or mechanical piano. The use by Sembène of this

dance music in this specific shot implies the idea or dream of summer

vacation, with the palm trees lining the Côte d’Azur, the beach, the sea,

the sun and farniente.

Once Diouana is settled and starts working in the apartment where she

cleans, cooks and washes, she starts to reminisce about Africa. The very

definition of work in the film is of paramount importance for, in the eyes of

her French employers, Diouana is good only for this type of work, follow-

ing the western conception of the division of labour that states that women

do domestic chores whereas men are in charge of public office (Lebeuf

1960: 93).

As a maid (bonne à tout faire), Diouana longs for her homeland, as life is

very tough for her in France; she has no friends, never goes out, and

always works, a reality far removed from the excitement she had in Dakar

when she was invited to go to France. At this juncture, the music shifts

from the rough piano chords to the kora, the African instrument with 21

strings. Just as the xalam represents traditional Africa in Borom sarret, so

too does the kora in Black Girl. When shacks are shown, one hears the kora

music. The sharp notes of the kora accompany Diouana’s sadness in France

as well as her slow descent into hell and, finally, death. Whenever Diouana

reminisces about home, the kora music accompanies her monologues in

voice-over. Conversely, whatever is intrinsically French is rendered by the

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 213

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 213 1/13/10 2:19:15 PM

dance tune on the piano bastringue, for example, when the employers have

invited their friends to have a meal in order to enjoy an African dish pre-

pared by Diouana.

In an interesting scene, however, the kora plays well into the French

quarter. The scene takes place in Dakar, prior to the family and Diouana’s

travel to France. When the kora music leaves the scene of the African

slum, the camera slowly turns towards the French quarter. Normally, this

neighbourhood is off limit to anything that slightly resembles an African

custom; the only African who is allowed into the quarter is the worker

who cleans, cooks, washes and looks after the children of the French peo-

ple. We are perhaps in the presence of a kind of synthesis of African and

European values or, very simply put, the French couple who employ

Diouana are being opportunistic, pretending to have accepted Africa but

deep down they have no respect for African culture. This posturing is dif-

ficult to admit, for, according to Sembène, with their air of superiority, it is

hard to imagine Frenchmen, the former colonial masters who are imbued

with their sense of cultural and linguistic superiority, acknowledging

African customs and languages. In this episode, the music of the kora blurs

the class lines and undermines the colonial division.

The next interesting scene concerning music in Black Girl happens in

Dakar just before Diouana leaves for France. She has a boyfriend who is try-

ing to discourage her from going to France. While the two are seated on a

bench in a park in downtown Dakar, the kora music can be heard in the

background; however, in this scene the notes are not sharp but rather mel-

low, thus denoting some kind of happiness, no matter if that happiness is

elusive and short-lived. At some point, Diouana leaves the bench, runs

toward the monument dedicated to the war dead, that is, the African soldiers

who fought in the French army in Europe during the First and Second World

Wars. A shot shows the government officials laying a wreath on the monu-

ment while the ominous sound of a French military drum can be heard in

the background; the drum here is the symbol of violence, danger and death.

In effect, we are in the presence of a war drum. This drum scene at the war

monument is an ideological one since Sembène is using sound and image to

highlight the debt the French owe to the Africans who have shed their blood

in order to defend la mère patrie yet have not received any recognition, a

theme Sembène will return to in Camp de Thiaroye (Diop 2004: 21–26).

At the end of the film, when Diouana commits suicide in France in the

bathtub, the scene is highlighted by the music of the kora. A brief obituary

is inserted in the local newspaper to the effect that a Negro woman has

committed suicide. The following shot, which shows the beach and the

sea, resounds with the same foxtrot tune on the piano bastringue, creating

an atmosphere that is both joyful and indifferent. The reading one can

have of this editing is that even though an African woman has just com-

mitted suicide, life goes on; people still go to the beach. Finally, at the end

of the film, the employers return to Dakar and the French man brings

Diouana’s belongings to her family and to her mother in particular. He

enters the slum, walking through the winding sandy streets looking for

Diouana’s house while a rhythmic choral chant in the Sereer language

accompanies him, for Diouana belonged to the Sereer ethnic group. The

mixed voices counteract the mechanical piano.

214 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 214 1/13/10 2:19:15 PM

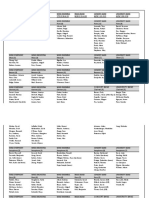

Figure 1: DVD cover Le Mandat (Wolof French Subtitles), Médiathèque des Trois Mondes (M3M).

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 215

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 215 1/22/10 7:04:13 PM

Three types of music are represented in Black Girl: The piano bastringue

for French culture and, for African culture, the kora, which is often rein-

forced by voice, as well as the rhythmic choral chant in Sereer highlight-

ing Diouana’s difficult life and tragic end. In Black Girl, as noted by Paulin

Vieyra (1972: 79), Sembène puts more emphasis on image than on sound

yet music serves as an important social and economic marker that

enhances the visual.

Mandabi/The Money Order

Mandabi (1968) features a gamut of musical and vocal expressions: the

kora, babies crying, the call of the muezzin, the sound of the xalam, the

beating of the drum and the chants of women (in particular Ibrahima

Dieng’s two wives). Each musical instrument highlights a specific theme

and concern.

The film starts with the sound of the kora, as Ibrahima Dieng, the

main character, is shown at the barber shop, being shaved; the shop is

under a tree and is actually not a real shop with walls, windows and

doors. Rather, like in many African scenes, the barber works in an open

space in the city. This opening scene denotes the routine of daily life. It is

neither a good nor a bad scene, just normal life. After that, the postman

enters Dieng’s compound in order to deliver the money order that was

sent from Paris by Dieng’s nephew. The nephew is an immigrant who

cleans the streets of Paris and sends remittances back home, as do many

African immigrés in France. The scene of the delivery of the money order

is an ordinary one as we hear the cries of a baby and see a flock of chil-

dren sitting on a mat while eating, and the women carrying out their

daily chores. The presence of so many children is the very symbol of the

extended African family, even in the city.

When Dieng returns home at lunchtime, his wives have prepared

for him a tasty rice dish. After having eaten, Dieng falls asleep only to

wake up after the midday prayer has passed; here Sembène chronicles

the presence of Islam in Senegal. This country is predominantly Muslim

and, as a good Muslim, Dieng must pray when the prayer is set, not

after. Dieng, however, has eaten so much that he has fallen into a deep

siesta. While he is asleep, the camera shows the roofs of the houses and

buildings of the city and one can distinctly hear the call of the muezzin.

This scene implies that Dieng is not a very good Muslim and when he

wakes up, he blames his wives for not waking him up at the prayer

time.

After the delivery of the money order, the news spreads all over town

that Dieng is rich now and all his friends and neighbours come to see him

asking for help, every one wanting a share of the money. Here the xalam

plays in the morning, at sunrise, at daybreak, thus heralding a new day, a

day full of hope. This is the opposite of the xalam in Black Girl since in the

latter film this instrument highlights hope and despair. Dieng is so sure

that he will soon get paid at the post office that he goes to the shop near

his house not only to take groceries on credit but also to borrow money for

his bus fare to the city. His hope is dashed, as he needs an ID card before

the money order is paid. This is the start of the roller coaster of Dieng’s

many misfortunes as he goes from one disappointment to another.

216 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 216 1/13/10 2:19:19 PM

Figure 2: Arame sings “sunu manda bi”. Still prepared by Samba Diop. Permission by Alain Sembene.

Beforehand, however, while Dieng was in the city, one of his relatives (a

westernized young man) came to visit him and found Dieng’s wives at the

entrance of the house. When the relative enquires as to Dieng’s wherea-

bouts, the wife responds that he went to the city; then the relative asks

whether there was a wedding and why there is drumming in the neigh-

bourhood. The wife simply declares that it is a party and that whenever

people hear that someone has money, they have to celebrate. Here, she is

alluding to the money order that everybody has heard that Dieng has

received from France; in short, la fête au village but within an urban con-

text. The drum here, in contrast to the one in Black Girl, is not a war drum

but rather the tom-tom that people beat when they are in a playful and

festive mood.

The scene in which Arame, one of Dieng’s wives, sings while washing

clothes is worth discussing. She is seated on a low stool inside the yard.

There is no musical instrument here but only the modulation and pitch of

the voice, along with inflections of the tone that convey hope:

(Sunu manda bi!)

Our money order!

This our money order

Our money order

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 217

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 217 1/13/10 2:19:19 PM

Oh! Mother our money order

When it gets here life will be joyous

For us who live in dearth

And who go to bed together with scarcity

We also live in poverty in the daytime

We spend our time asking for credit and begging

However we are in peace Diagne

We still have a little to live by

You have made us proud Diagne

For all we do is just begging

May you have long life

We will never get tired Diagne [of praying for you]

Our money order!

Arame is interrupted by the irruption of the water seller into the yard of

the compound. In an angry voice, the man demands that Arame pay the

debt she owes him for water taken on credit. Arame angrily answers him

that she will pay when she gets the money (understand here when the

money order is paid to Dieng the husband). Arame then resumes her

singing:

We would like to pay all our debts

And help those who are close to us

However we are in peace Diagne

We still have a little to live by

Whosoever says that money is bad

That is because you do not have it

If you have money

You can buy anything you want.

Thus, the final device used by Sembène in Mandabi, as far as music and

voice are concerned, is the scene in which Dieng’s wife sings while work-

ing in the house (cooking, cleaning and washing) as shown above. The

performance of the song denotes a message of hope, a forward-looking

attitude on the part of Arame. This is in sharp contrast to the Sereer

mournful dirge at the end of Black Girl, when the French employer returns

Diouana’s belongings to her family in Dakar after her death in France.

Music in Mandabi is a positive element and renders the various moods and

moments of the characters. If music in Borom sarret is a tale of marginali-

zation, in contrast, in Mandabi, music is a tale of hope.

Emitaï

If we have Sereer chants in Black Girl, and a Wolof song in Mandabi, in

Emitaï (1972), we are in the presence of Diola culture. The Diola inhabit

the Casamance region in the south of Senegal. Emitaï chronicles an epi-

sode of the French colonial times in Africa, in particular during the Second

World War when the French administration needed African soldiers to go

and fight in France and requested the rice to feed the same soldiers. The

218 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 218 1/13/10 2:19:23 PM

Figure 3: DVD cover Emitaï (French and Diola, French subtitles), Médiathèque des Trois Mondes

(M3M).

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 219

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 219 1/20/10 1:44:47 PM

solution found by the French administration was to take by force the rice

from the Diola women who had hidden it. The women consider the rice as

the fruit of their sweat which they obtained from farming. As observed by

David Murphy (2000: 109), Emitaï is among Sembène’s most symbolic,

non-realistic works as the film-maker moves away from the social realism

of his earlier films. Contrary to his previous films, in Emitaï, Sembène does

not use stringed instruments; rather, in order to adhere to Diola culture

and customs, priority is given to drum and voice in the film and indeed the

beating of the drum permeates the whole film. If in Mandabi the Wolof

drum is played in a festive mood, in Emitaï the Diola drum is an instru-

ment of resistance (to French domination). Moreover, the drum is an

instrument of mystery, a form of language that only the initiated can com-

prehend. Thus, the French officer has to ask the African sergeant what the

meaning of the drum is; one can surmise that the permanent and consist-

ent thud created by the drum must be annoying for the French officers. In

effect, in Emitaï, Sembène uses the drum as a trope of difference, of foreign-

ness. Nevertheless, the presence of the drum is a normal feature if we take

into account the fact that the events depicted in the film take place in war-

time. The Diola drum is cut out from a tree trunk that is horizontally laid

down. It is used as a means of sending messages and, depending on the

number and duration, the receiver is able to decode the beats: there is

clear and present danger, the elders are called to a meeting at the shrine,

the soldiers of the French colonial army are about to attack the village.

Likewise, vocal expression has different meanings: when the men and

women are cultivating the rice field, the chant they intone is related to

work and labour; when the women fetch wood for cooking and when the

palm-wine tapper climbs the palm tree in order to harvest the palm wine,

all these activities are accompanied by singing. When the women refuse to

give away their rice, as punishment, they are assembled in the middle of

the village and told by the French commander that if they do not bring the

hidden rice, they will stay where they are. Thereupon, the women start

singing but this time it is a song of defiance, a battle of wills as to who is

going to give up first: the authorities or the women. Sembène goes further

by creating dialectics predicated on the pairing of voice with silence. The

film-maker uses silence as a form of expression to the effect that when the

French commander or the African sergeant talks to the villagers, the latter

choose not to answer as they feel they are oppressed. Thus, the silence of

the villagers in the face of the French authorities is a form of contempt.

When facing injustice and the uncontrolled use of force, silence can be a

powerful weapon, even if it has its limitations. How long can one be silent

in front of injustice? Sooner or later one has to speak up and that is the

reason why the elders call a meeting of the council at the shrine, in order

to discuss what attitude to adopt vis-à-vis the danger posed by the French.

In Emitaï, Sembène also uses chant and song as a source of confu-

sion. There is an episode in the film when the African soldiers’ discussion

bears on General de Gaulle and Marshal Pétain. In following his logic,

the African soldier rightly and correctly asks how a general can be above

a marshal, if we take into account the hierarchy that prevails in the

army. Actually, the African soldiers were not aware of the fact that the

Vichy government lost command and authority over most of its overseas

220 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 220 1/13/10 2:19:24 PM

Figure 4: Emitaï: The women’s song of defiance. Still prepared by Samba Diop. Permission by Alain

Sembène.

territories (including French West Africa) and the exiled government of

Free France under the aegis of General de Gaulle was now in command.

Not only were the African soldiers chanting the name of Pétain a few

days earlier, but they woke up one day to see the photo of Pétain being

taken off the walls and being replaced by a poster showing a photo of de

Gaulle. Consequently, the African soldiers received an order not to sing

‘Pétain’. From that moment on, de Gaulle had to be praised. No wonder

the poor soldiers became confused. Moreover, they did not understand

anything about the complexities of French metropolitan politics.

Thus, both drum and voice serve as a means of resistance and defiance.

Djimeko, one of the elders, dies in combat. He had chosen to fight the French

rather than compromise. During Djimeko’s funeral, the song is a dirge that

befits his bravery. In this scene, vocal expression supersedes musical instru-

ment. Sembène’s tour de force in Emitaï resides in his clever and judicious

usage of nature’s noises: he renders the exact geographical reality and the

topography of the Casamance region, which is dominated by the mangrove.

Thus, because of the presence of so much water, the dugout is a convenient

means of transportation. One hears the constant noise made by the water

when the dugout is slowly gliding on the surface of the waters. In the same

order of things, the songs of the bird are heard as well as the bleating of the

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 221

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 221 1/13/10 2:19:24 PM

goats and other noises made by pigs and hens. Thus, Sembène describes the

various activities of Diola society, in addition to showing the symbiosis that

exists between nature and the population. The Diola have a high respect for

their environment because they get their sustenance from nature and their

gods and goddesses reside within and across nature.

Faat Kine

When we consider Sembène’s film Faat Kine, which came out in 2001, there

is a big surprise in it as the film-maker makes use of music by Youssou Ndour,

a well-known musician in Senegal, Africa and beyond. It is important, how-

ever, to stress that Ndour did not write the musical score of the film. Rather,

there is a scene in the film where Faat Kine’s children’s celebrate their suc-

cess at their secondary-school final examination (the baccalauréat). Thus,

during the party, Ndour’s songs are played on a tape player and everybody is

dancing. If we compare Faat Kine to Xala (1975), an earlier film by Sembène,

in Xala there is an orchestra (Star Band) which performs during El Hadj

Abdou Kader Beye’s wedding. Beye, the main protagonist of the film, belongs

to the new bourgeoisie, the nouveaux riches and as such is a member of the

new African elite that has just replaced the French colonizer.

The contrast between the two films is actually parallel to the evolution

of Senegalese society. As a shrewd observer, Sembène notices that in the

1970s, only the rich (like Beye) had access to bands, mostly upon occa-

sions such as naming ceremonies and weddings. However, thirty years

later, not only has popular music changed in Senegal but it has also become

more democratic and egalitarian. Thanks to the prodigious technological

development of the tape player and cassette industries as well as of local

radios, almost everybody now has access to popular music and to mega

stars such as Youssou Ndour. Thus, if in Xala music is used by Sembène as

a social-class marker, in Faat Kine that marker disappears. Music in Faat

Kine is neutral, bland and undifferentiated except in the scene where

Ndour’s music is played. In the rest of the movie, we hear a repetition of the

notes of a piano telling us that daily life is monotonous and not much is

happening. Faat Kine, the urbane central character of the eponymous film,

wakes in the morning, goes to work as the manager of a petrol station and

then returns home, just like the majority of the people. Music is not ideo-

logical in Faat Kine whereas in most of Sembène’s films the film-maker uses

music as a platform to get a specific message across.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a clear-cut line in Sembène’s films, at least in the ones

that are discussed above: in his first films (Borom sarret, Black Girl and

Mandabi) he is an adept of the social realist mode, whereas with Emitaï, the

film-maker clearly departs from that mode. In the same order of things, in

the first three films, the film-maker makes abundant use of traditional African

instruments such as the kora, the xalam the drum, as well as traditional songs

in order to highlight the cultural codes that are inherent to the various

Senegalese ethnic groups that he is describing. He also uses the piano (or its

mechanical version, the pianola) and classical music as symbols of western

and European life, of French culture and civilization and of the French colo-

nial experience in Africa. However, in Emitaï, Sembène relies less on musical

222 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 222 1/13/10 2:19:28 PM

instruments to convey messages; he relies mostly on nature and the noises

coming from it in order to describe faithfully the Diola people.

In the final analysis, Ousmane Sembène uses music and vocal expres-

sion as a form of writing to the effect that songs and music render the eth-

nic, linguistic and cultural customs of the various ethnic groups that

inhabit the Senegalese geographical space. At the same time, however, the

film-maker has not forgotten the French colonial experience in Africa and

the many disruptions that experience has caused to the lives of Africans. In

the films discussed above, Sembène attempts to show the beauty of African

culture thanks to the presence of music. In doing so, he asserts a certain

pride by putting a focus on traditional Senegalese ethnic musical instru-

ments such as the xalam, the kora and the drum. However, Sembène is also

careful and avoids an exaggerated focus on ethnicity. To that end, there is

a very modern substratum in his films as he treats local themes but also

opens up to universal ones. Voice is also an integral component as Sembène

uses in his films the griot praise tradition (Borom sarret), in addition to work

songs as evidenced by Arame in Mandabi. For Sembène, music is an art

form that is used to express specific messages but it is also a form of ethno-

graphic writing which beautifully complements the image.

Cited films

Sembène, Ousmane (1963), Borom sarret/The Cart Driver (20 min.), Les Actualités

Françaises/ Filmi Doomireew, France/Senegal, distr. M3M/New Yorker Video

(title: The Wagoner)/BFI.

—— (1966), La Noire de…/Black Girl (60 min.), Les Actualités Françaises/Filmi

Doomireew, France/Senegal, distr. M3M/New Yorker Films.

—— (1968), Mandabi/Le Mandat/The Money Order (90 min.), Filmi Doomireew/

Comptoir Français du Film, Senegal/France, distr. M3M/New Yorker Films.

—— (1972), Emitaï/Dieu du Tonnerre/God of Thunder (95 min.), Filmi Doomireew/

Myriam Smadja, Senegal/France, distr. M3M.

—— (1975), Xala/The Curse (116 min.), Filmi Doomireew/Société Nationale de

Cinéma, Senegal, distr. M3M/New Yorker Films.

—— (1976), Ceddo (120 min.), Filmi Doomireew, Senegal, distr. M3M/Homeciné.

—— (2001), Faat Kine (120 min.), ACCT/Canal & Horizons/EZEF/Stanley

Thomas Johnson Stiftung/California Newsreel/Films Terre Africaine/Filmi

Doomireew, France/Germany/Switzerland/USA/Cameroon/Senegal, distr.

California Newsreel.

Sembène, Ousmane and Faty Sow, Thierno (1988), Camp de Thiaroye (147 min.),

SNPC/Films Kajoor/SATPEC/ENAPROC, Senegal/Tunisia/Algeria, distr. M3M/

New Yorker Films.

References

Bakari, Imruh (2000), ‘Introduction’, in June Givanni (ed.), Symbolic Narratives/

African Cinema: Audiences, Theory and the Moving Image, London: British Film

Institute, pp. 3–24.

Bebey, Francis (1975), African Music: A People’s Art, New York: Lawrence Hill.

Chion, Michel (1995), La Musique au cinéma, Paris: Fayard.

Diop, Samba (2004), African Francophone Cinema, New Orleans: University Press

of the South.

Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène 223

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 223 1/13/10 2:19:28 PM

Gugler, Josef (2003), African Film: Re-Imagining a Continent, Bloomington, Oxford

and Cape Town: Indiana University Press, James Currey and David Philip.

Lebeuf, Annie (1960), ‘Le rôle de la femme dans l’organisation politique des

sociétés africaines’, in Denise Paulme (ed.), Femmes d’Afrique noire, Paris:

Mouton, pp. 93–119.

Murphy, David (2000), Sembène: Imagining Alternatives in Film and Fiction, Oxford

and Trenton, NJ: James Currey and Africa World Press.

Niang, Sada (1996), ‘Orality in the films of Ousmane Sembène’, in Sheila Petty

(ed.), A Call to Action: The Films of Ousmane Sembène. Trowbridge, UK: Flicks

Books, pp. 56–66.

Thackway, Melissa (2003), Africa Shoots Back: Alternative Perspectives in Sub-

Saharan Francophone African Film, Bloomington, Oxford and Cape Town:

Indiana University Press, James Currey and David Philip.

Vieyra, Paulin S. (1972), Ousmane Sembène Cinéaste, Paris: Présence Africaine.

Suggested citation

Diop, S. (2009), ‘Music and narrative in five films by Ousmane Sembène’, Journal

of African Cinemas 1: 2 pp. 207–224, doi: 10.1386/jac.1.2.207/1

Contributor details

Samba Diop teaches African literatures in French and English as well as African

cinema. His special research interest is African epics in Senegal and Gambia. He

has edited and translated versions of the epics of Ndiadiane Ndiaye and of El Hadj

Omar Tall. He has also edited two books on postcolonial studies (Fictions africaines

et postcolonialisme; L’Écrivain peut-il créer une civilisation?). He is the author of two

books on African studies (Discours nationaliste et identité ethnique à travers le roman

sénégalais and African Francophone Cinema) and of one volume of short stories (À

Bondowé, les lueurs de l’aube).

Contact: The Institute of Cultural Studies and Oriental Languages (IKOS), University

of Oslo, Norway.

E-mail: sbkdiop@yahoo.co.uk

224 Samba Diop

JAC_1.2_art_Diop_207-224.indd 224 1/13/10 2:19:28 PM

You might also like

- Returning Home Djibril Diop Mambety S Hy NesDocument16 pagesReturning Home Djibril Diop Mambety S Hy NesSourodipto RoyNo ratings yet

- The French Reflexive Verb and Its Urhobo EquivalentDocument10 pagesThe French Reflexive Verb and Its Urhobo EquivalentPremier PublishersNo ratings yet

- Hisory of Bani HilalDocument7 pagesHisory of Bani Hilaltomlec100% (1)

- Le Choc Des Décolonisations de La Guerre D'algérie Aux PrintempsDocument556 pagesLe Choc Des Décolonisations de La Guerre D'algérie Aux PrintempsaksilNo ratings yet

- Daisy Marsh - Missionary To The KabylesDocument6 pagesDaisy Marsh - Missionary To The KabylesDuane Alexander Miller BoteroNo ratings yet

- Screening Morocco Contemporary Film in A Changing SocietyDocument2 pagesScreening Morocco Contemporary Film in A Changing SocietyJamal BahmadNo ratings yet

- National Symbols of UKDocument4 pagesNational Symbols of UKDumitru Cereteu100% (1)

- Bischoff - West African CinemaDocument12 pagesBischoff - West African CinemawjrcbrownNo ratings yet

- The French New Wave: Andre BazinDocument4 pagesThe French New Wave: Andre BazinAkmal NaharNo ratings yet

- Tamazight Manuel Scolaire Algerie 1 Annee MoyenneDocument131 pagesTamazight Manuel Scolaire Algerie 1 Annee Moyennemoussa chabaneNo ratings yet

- Violence Et Rebellion Chez Trois Romancières de LAlgerie ContemporaineDocument220 pagesViolence Et Rebellion Chez Trois Romancières de LAlgerie ContemporaineAnonymous saZrl4OBl4No ratings yet

- French LyricsDocument242 pagesFrench Lyricsapi-3804640100% (1)

- Lost (Andfound?) in Translation:Feminisms InhemisphericdialogueDocument18 pagesLost (Andfound?) in Translation:Feminisms InhemisphericdialogueLucas MacielNo ratings yet

- Africans and The Politics of Popular CultureDocument347 pagesAfricans and The Politics of Popular CulturenandacoboNo ratings yet

- Afro SuperhAfro-superheroes: Prepossessing The Futureeroes Prepossessing The FutureDocument5 pagesAfro SuperhAfro-superheroes: Prepossessing The Futureeroes Prepossessing The FutureAlan MullerNo ratings yet

- A Cinematic Refuge in The Desert: The FiSahara Film FestivalDocument16 pagesA Cinematic Refuge in The Desert: The FiSahara Film Festivalstefanowitz2793No ratings yet

- Karens Weekend Past Simple ReadingDocument1 pageKarens Weekend Past Simple ReadingCarmen GloriaNo ratings yet

- Silverstein, "States of Fragmentation in North Africa"Document9 pagesSilverstein, "States of Fragmentation in North Africa"Paul SilversteinNo ratings yet

- Literary Context q1Document30 pagesLiterary Context q1Jessa AmidaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 80.200.25.33 On Fri, 26 May 2023 17:42:58 +00:00Document4 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 80.200.25.33 On Fri, 26 May 2023 17:42:58 +00:00Marthe BwirireNo ratings yet

- Q4 Lasw1 Music10 A4Document6 pagesQ4 Lasw1 Music10 A4Ma Quin CioNo ratings yet

- Presses Universitaires de La Méditerranée: Enacting Postcolonial Translation: VoiceDocument24 pagesPresses Universitaires de La Méditerranée: Enacting Postcolonial Translation: VoiceEliserNo ratings yet

- How Silver-Sweet Sound Lovers' Tongues': The Music of Love and Death in Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet'Document8 pagesHow Silver-Sweet Sound Lovers' Tongues': The Music of Love and Death in Franco Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet'for.peterbtopenworld.comNo ratings yet

- This Is Not A Pipe: Reflexivity, Fictionality, and Dialogism in Sembene's Films - Jonathon RepineczDocument18 pagesThis Is Not A Pipe: Reflexivity, Fictionality, and Dialogism in Sembene's Films - Jonathon RepineczJonathon RepineczNo ratings yet

- Le Cinéma de Sembène Ousmane, Une (Double) Contre-EthnographieDocument47 pagesLe Cinéma de Sembène Ousmane, Une (Double) Contre-EthnographiecrisrobuNo ratings yet

- Global Ostinato WorksheetDocument3 pagesGlobal Ostinato WorksheetZach ToddNo ratings yet

- Music and Narrative in Howl's Moving Castle and Other Hisaishi Film WorksDocument13 pagesMusic and Narrative in Howl's Moving Castle and Other Hisaishi Film WorksVivie Lee100% (2)

- Comp Stylistics L2!20!21Document47 pagesComp Stylistics L2!20!21Menhera MenherovnaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 (Music) Grade 10Document9 pagesModule 2 (Music) Grade 10mary janeNo ratings yet

- Module 2 (Music) Grade 10Document9 pagesModule 2 (Music) Grade 10mary jane100% (1)

- Grade 7 LasDocument15 pagesGrade 7 LasLanie BatoyNo ratings yet

- Music 8 - Q4 - Week 2Document9 pagesMusic 8 - Q4 - Week 2Allenmay LagorasNo ratings yet

- Music 8 Q1-Week 1&2Document16 pagesMusic 8 Q1-Week 1&2Angelica SantomeNo ratings yet

- Melodic and Rhythmic Aspects of Indigenous African MusicDocument14 pagesMelodic and Rhythmic Aspects of Indigenous African MusicIsabelaNo ratings yet

- The Film WHOSE IS THIS SONG NationalismDocument17 pagesThe Film WHOSE IS THIS SONG NationalismSU CELIKNo ratings yet

- Headstart Wicked Questions-1Document2 pagesHeadstart Wicked Questions-1Callum LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Music9 Q4 Week7-8Document10 pagesMusic9 Q4 Week7-8ELJON MINDORONo ratings yet

- 'Whose Is This Song?': Nationalism and Identity Through The Lens of Adela PeevaDocument23 pages'Whose Is This Song?': Nationalism and Identity Through The Lens of Adela PeevaRa AykNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document21 pagesModule 4JC MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Josefino Tulabing Larena, AB, CPS, MPADocument51 pagesJosefino Tulabing Larena, AB, CPS, MPADorothy Joy AmbitaNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 8 Q4 Week 2Document10 pagesMAPEH 8 Q4 Week 2Coach Emman Kali SportsNo ratings yet

- Week 1 IndonesiaDocument10 pagesWeek 1 Indonesiadanaya fabregasNo ratings yet

- G7 LAM 1st QuarterDocument73 pagesG7 LAM 1st QuarterJoselito CepadaNo ratings yet

- Ousm Ne: SembeneDocument218 pagesOusm Ne: SembeneWilliam Fernando OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Tschofen London Journal of Canadian StudiesDocument20 pagesTschofen London Journal of Canadian StudiesMilenaKafkaNo ratings yet

- Agawu African Imagination CH 5 Melodic ImaginationDocument42 pagesAgawu African Imagination CH 5 Melodic ImaginationNicholas RaghebNo ratings yet

- Reviewer in CPARDocument3 pagesReviewer in CPARJulienne SemaniaNo ratings yet

- Grid and Planning GuideDocument10 pagesGrid and Planning Guideapi-357689913No ratings yet

- 5 Voices and Singers: Susan RutherfordDocument22 pages5 Voices and Singers: Susan RutherfordJilly CookeNo ratings yet

- Music10 Q1 Week6 LAS1Document1 pageMusic10 Q1 Week6 LAS1Karen Mae Ariño LaraNo ratings yet

- Musical Figures of Enslavement and Resistance in Semzaba's Kiswahili Play TendehogoDocument17 pagesMusical Figures of Enslavement and Resistance in Semzaba's Kiswahili Play TendehogoJuan Diego González BustilloNo ratings yet

- Music 9 Module 7Document6 pagesMusic 9 Module 7ItsDaneNo ratings yet

- Music Arts 10 Las q4 Weeks 1 4Document7 pagesMusic Arts 10 Las q4 Weeks 1 4Anna AngelaNo ratings yet

- Forms of Multimedia in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesForms of Multimedia in The Philippinesivi pearl dagohoyNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 10 Q4 Week 1Document9 pagesMAPEH 10 Q4 Week 1Arvic King De AmboyyNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 Arts q4 Module 2wordDocument18 pagesGrade 7 Arts q4 Module 2wordKyla MarinoNo ratings yet

- Theatreandperformanceartsonstageandon 170506143128Document51 pagesTheatreandperformanceartsonstageandon 170506143128Jennalyn GomezNo ratings yet

- Chinua Achebe PoemsDocument8 pagesChinua Achebe PoemsOlivia TremblayNo ratings yet

- Q4 Las Grade 8 Music Week 1Document11 pagesQ4 Las Grade 8 Music Week 1Xam BoNo ratings yet

- CULTURE SKETCHES. CuLture Sketches. HOLLY Peters-Golden. Sixth Edition. KeY Updates To This EditionDocument321 pagesCULTURE SKETCHES. CuLture Sketches. HOLLY Peters-Golden. Sixth Edition. KeY Updates To This EditionMaddah Hussain100% (9)

- Music in Peace Building Mawuena Komla AgDocument73 pagesMusic in Peace Building Mawuena Komla AgAmsalu G. TsigeNo ratings yet

- Popular Culture and Oral Traditions in African FilmDocument10 pagesPopular Culture and Oral Traditions in African FilmAmsalu G. TsigeNo ratings yet

- Race and Representation in Post - Apartheid Music, Media and FilmDocument5 pagesRace and Representation in Post - Apartheid Music, Media and FilmAmsalu G. TsigeNo ratings yet

- Today We Discussed AboutDocument108 pagesToday We Discussed AboutKaye UyvicoNo ratings yet

- Bela Hamvas - The Seventh Symphony and The Metaphysics of MusicDocument11 pagesBela Hamvas - The Seventh Symphony and The Metaphysics of MusicMilos777100% (1)

- 00 Fall 2022 Placements 8.31.22Document4 pages00 Fall 2022 Placements 8.31.22Parkerman101No ratings yet

- Hay Teo Foana I Kristy-Conducteur-et-partiesDocument6 pagesHay Teo Foana I Kristy-Conducteur-et-partiesSamuthiah ANDRIANARIVELONo ratings yet

- Antonín DvořákDocument6 pagesAntonín DvořákFor Valor100% (2)

- "The Peanuts Movie" Jazz Pianist David Benoit To Perform Christmas Tribute To Charlie Brown Dec. 19Document4 pages"The Peanuts Movie" Jazz Pianist David Benoit To Perform Christmas Tribute To Charlie Brown Dec. 19dazeeeNo ratings yet

- Perfect Ed Sheeran Chords GuitarDocument3 pagesPerfect Ed Sheeran Chords GuitarIrina MorărașuNo ratings yet

- David Ridley Composition CVDocument2 pagesDavid Ridley Composition CVapi-307896639No ratings yet

- Parokya Ni Edgar Arranged By: James Luis Leynes: Voice 60Document7 pagesParokya Ni Edgar Arranged By: James Luis Leynes: Voice 60anon526No ratings yet

- Guitar Success Checklist v2: Action PlanDocument11 pagesGuitar Success Checklist v2: Action PlanMinh LeNo ratings yet

- CanonVlPfFirst PDFDocument2 pagesCanonVlPfFirst PDFRoberto JarilloNo ratings yet

- Coppelia Lake BRDocument41 pagesCoppelia Lake BRjoeNo ratings yet

- Death and The Maiden Violin 1Document17 pagesDeath and The Maiden Violin 1Tsetini AthinaNo ratings yet

- Incredibile Rock Blues Guitar SoloDocument5 pagesIncredibile Rock Blues Guitar SoloLuca BifulcoNo ratings yet

- Bach - Badinerie PDFDocument4 pagesBach - Badinerie PDFsorrogongon100% (1)

- Baritone Euphonium 0113Document3 pagesBaritone Euphonium 0113Len CumminsNo ratings yet

- Butterfly ScoreDocument3 pagesButterfly ScoreCraig Siewai PerkintonNo ratings yet

- Black Rhythm Revolution!Document2 pagesBlack Rhythm Revolution!WikibaseNo ratings yet

- Digital Booklet - Mission - Impossible PDFDocument8 pagesDigital Booklet - Mission - Impossible PDFДенис СалаховNo ratings yet

- Super Smash Bros. Brawl - TUBA1Document2 pagesSuper Smash Bros. Brawl - TUBA1vladsoadNo ratings yet

- Saho PhoneDocument18 pagesSaho PhoneavaigandtNo ratings yet

- Libro de Ingles (Jennifer Mariana Sanchez Justillo) - 49-118Document70 pagesLibro de Ingles (Jennifer Mariana Sanchez Justillo) - 49-118Solange Riofrio100% (1)

- Temps Clar - Wind QuintetDocument8 pagesTemps Clar - Wind QuintetgarciaromeromarioNo ratings yet

- Music Video QuestionnaireDocument11 pagesMusic Video QuestionnaireEmmanuella ThomasNo ratings yet

- Converge HistoryDocument5 pagesConverge HistoryfrankiepalmeriNo ratings yet

- The 9 Rivers Awards Composition Competition (RACC) 2020: - RegulationsDocument7 pagesThe 9 Rivers Awards Composition Competition (RACC) 2020: - RegulationsOscar GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Imslp92729 Pmlp53438 Nielsen Symph1scceDocument159 pagesImslp92729 Pmlp53438 Nielsen Symph1scceRasmusNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ THI THỬ SỐ 40- NGÀY 17062022-BIÊN SOẠN CÔ PHẠM LIỄUDocument7 pagesĐỀ THI THỬ SỐ 40- NGÀY 17062022-BIÊN SOẠN CÔ PHẠM LIỄUMai KateNo ratings yet

- Uncle Rod's Ukulele Boot Camp (Rev2011)Document10 pagesUncle Rod's Ukulele Boot Camp (Rev2011)aeon-lakes100% (5)

- C - MÚSICA - ARRANJAMENTS - Eurovision Junior Parts - 01 OboesDocument1 pageC - MÚSICA - ARRANJAMENTS - Eurovision Junior Parts - 01 OboesAmigos de la Música CaudeteNo ratings yet