Professional Documents

Culture Documents

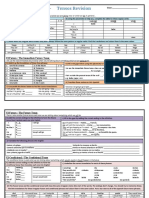

D2 Teribe

Uploaded by

Peter JohnsonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

D2 Teribe

Uploaded by

Peter JohnsonCopyright:

Available Formats

Information structure in Teribe (Chibchan)

J. Diego Quesada Univ. Nacional, Costa Rica (in collaboration with project D2 Typology of Information Structure)

1. Object language One of the 15 currently living Chibchan languages (spreading from Northeastern Honduras, through the Atlantic coast of Nicaragua, most of Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, to the West of Venezuela), Teribe is spoken by some 2,000 people in the province of Bocas del Toro, in Northwestern Panama, and by 6 people all born and raised in Panama- in Costa Rica. The data were elicited in January 2006 in Costa Rica; the participants are all adults speakers of the language, with ages ranging from 30 to 50.

3. Empirical observations Of interest for the objectives of D2 are the inversion construction and the role of obviative NPs, especially in comparison with the function of passive sentences in languages like English and German. The Teribe informants produced these structures in the elicitation task Visibility, where the patient is given and the agent new. The following example is an illustration of the discourse function of this construction:

Fig. 1 Panama

(1)

kwozir-wa

child-DIM

dulas jek zron pang

boy go go run hang

kl-ara.

CLF.ANIMATE-one

kwozir-wa

child-DIM

jek zron pang

run hang

kl-ara

CLF.ANIMATE-one

li

ta-kz-a

ba

klara d

REL kick-SUD-3.SG 3.SG.POSS mate OBV A little boy is running. The boy who was running was suddenly kicked by his mate.

2. Information Structure MARKERS OF INFORMATION-STRUCTURE STATUS In addition to unmarked mechanisms such as unmarked word orders and zero anaphora, the language has four markers of information-structure status: the topic marker li, the focus marker omgo, the contrastive focus marker ra, and a rather interesting focus marker, om, whose role is to keep a newly activated participant as new until it either disappears or becomes established as a new topic.

In contrast, in the conditions, in which the patient is new and the agent is given, there is no inversion. It is therefore important to search for contexts in which Teribe uses inversion, but German or English reject it. One such context is that of cases in which the agent is the questioned information; this becomes apparent in the experiment Anima: > where the agent is questioned, with either a wh-question or an alternative question (the man or the woman), the informants produce inverted replies.

(2)

kok

place

pansho

cloud

komo

up

ara

many

shko

in

These markers combine with word order to create a wealth of foregrounding structures, similar in function to mechanisms such as passives, clefts or left/right dislocations in other languages.

ga

ye shng

shng

stand

yuk

lamp

k

see

and that who

yuk k

domer

WORD ORDER SOV order is used discourse-initially to ground participants, and to reinforce their identity in some discourse passages; there is a tendency for participants to appear as full noun phrases in this order. The more frequent OV-s order, where -s stands for a personindexing suffix, is used for running discourse. In principle, the SOV order excludes the indexing of the subject and the OV-s does not allow the presence of a free subject noun phrase. Both orders can be regarded as being in complementary distribution. As for intransitive clauses, the discourse equivalent of the SOV order is SV, while the intransitive counterpart of OV-s is V (5).

lamp see stand man OBV There where there are many clouds high up, who is looking at the lamp? The lamp, the man sees it.

In these discourse conditions, no passive is possible. This leads to the conclusion that in both English and German passive is used when the patient is given information (not the whole VP), whereas in Teribe the inversion construction is used when the agent is new, or has at least recently become new in discourse, as it is possible to encounter inverted constructions with the obviative NP marked with the topic marker li. In cases in which the agent is new and the VP is given, Teribe prefers the inversion construction, whereas both English and German use active (non-passive) sentences. In such cases the tendency in English is to use cleft constructions. Although the inversion construction resembles a passive, two arguments speak against analyzing it as such. 1. patient suppression is far more common than agent suppression; 2. the grammatical relations in the inversion construction remain unaltered (the postverbal NP is subject and the preverbal NP is the object); there is no promotion to subjecthood.

INVERSION The inverse construction is characterized by a) word order inversion (OVSd), where S is a full noun phrase and the object of the clause remains in its preverbal position; b) aspectual marking with agreement in some cases but not in others, but with a finite verb form in all cases; and, c) direct marking on the obviate NP (d), which is a pragmatic type of inversion.

Finally, it should be mentioned that use of the information-structure markers is to a large extent speaker-based, which makes them rather unpredictable. Generalizations as to what constructions to expect in which contexts can be readily made on the bases of word order rather than on the use of the markers per se.

4. References Quesada, J. Diego. 2002. Narraciones teribes. Munich: Lincom-Europa. Quesada, J. Diego. 2000a. A Grammar of Teribe. Munich: Lincom-Europa. Quesada, J. Diego. 2000b.Word order, participant-encoding and the alleged ergativity in Teribe. International Journal of American Linguistics (IJAL): 66 (1): 98-124.

http://www.sfb632.unihttp://www.sfb632.uni-potsdam.de/

Funded by the DFG

m o c.l i a m t o h @ p a d a s e u q dj

You might also like

- Informal Speech: Alphabetic and Phonemic Text with Statistical Analyses and TablesFrom EverandInformal Speech: Alphabetic and Phonemic Text with Statistical Analyses and TablesNo ratings yet

- Ergativity R. M. W. DixonDocument81 pagesErgativity R. M. W. DixonAmairaniPeñaGodinezNo ratings yet

- THe Idiolect, Chaos and Language Custom Far from Equilibrium: Conversations in MoroccoFrom EverandTHe Idiolect, Chaos and Language Custom Far from Equilibrium: Conversations in MoroccoNo ratings yet

- Joseph Greenberg - Edicion ReynosoDocument31 pagesJoseph Greenberg - Edicion ReynosoManuel MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Basically in Singapore English: Claudia LangeDocument14 pagesBasically in Singapore English: Claudia LangeMohammad MansouriNo ratings yet

- Binder 1Document38 pagesBinder 1Danijela VukovićNo ratings yet

- English LanguageDocument38 pagesEnglish LanguageAntichu Codilloclla CodillocllaNo ratings yet

- Dissecting Discourse: An Analysis of LanguageDocument23 pagesDissecting Discourse: An Analysis of LanguageMedian Najma FikriyahNo ratings yet

- Transfer in Interlanguage Pragmatics New Research AgendaDocument20 pagesTransfer in Interlanguage Pragmatics New Research AgendaAhmed S. MubarakNo ratings yet

- Pergamon: Language SciencesDocument24 pagesPergamon: Language SciencesĐạt Vũ Súc VậtNo ratings yet

- Handout Chapter 7Document7 pagesHandout Chapter 7Stephanie ChaseNo ratings yet

- Pragmatic Functions of Prosodic Features in Non-Lexical UtterancesDocument6 pagesPragmatic Functions of Prosodic Features in Non-Lexical Utterancesوسيم العليNo ratings yet

- 09 Structural Patterns IiDocument16 pages09 Structural Patterns IiNieves RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Shabani 2005 AnticipationDocument26 pagesShabani 2005 AnticipationSasha SirovecNo ratings yet

- Representative Descriptive ProblemsDocument8 pagesRepresentative Descriptive Problemsbc230405476mchNo ratings yet

- Jezikoslovlje 1 04-1-005 Panther ThornburgDocument5 pagesJezikoslovlje 1 04-1-005 Panther Thornburggoran trajkovskiNo ratings yet

- ANALYSIS OF PSYCHOLINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE PROCESSINGDocument12 pagesANALYSIS OF PSYCHOLINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE PROCESSINGYasir ANNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Universals: Ian Roberts, Chapter 10Document11 pagesLinguistic Universals: Ian Roberts, Chapter 10Michael SchiffmannNo ratings yet

- GreenbergDocument42 pagesGreenbergAlexx VillaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic v8 Stephanie PourcelDocument14 pagesLinguistic v8 Stephanie PourcelSergio BrodskyNo ratings yet

- 3siyanova and Schmitt CMLR 2008Document31 pages3siyanova and Schmitt CMLR 2008Darin M SadiqNo ratings yet

- Aula Ling 12Document6 pagesAula Ling 12Oliver DumaskNo ratings yet

- DIXON - ErgativityDocument81 pagesDIXON - ErgativitylauraunicornioNo ratings yet

- Antipassive Derivations in Sino-TibetanDocument20 pagesAntipassive Derivations in Sino-TibetanMaxwell MirandaNo ratings yet

- T 6 Indepth 1Document35 pagesT 6 Indepth 1Carlos RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Comparing Romance and Germanic LanguagesDocument7 pagesComparing Romance and Germanic LanguagespepitoNo ratings yet

- John Benjamins Publishing CompanyDocument26 pagesJohn Benjamins Publishing CompanyDomonkosi ÁgnesNo ratings yet

- Code Mixing Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesCode Mixing Literature Reviewc5dg36am100% (1)

- Interface Between Morphology and Syntax in Garífuna Sentence StructuresDocument10 pagesInterface Between Morphology and Syntax in Garífuna Sentence StructuresAshreen Mirza100% (1)

- Saab 23 Agree Agreement DDocument25 pagesSaab 23 Agree Agreement DCésar RamosNo ratings yet

- GivonT. - The Story of ZERODocument30 pagesGivonT. - The Story of ZEROДарья БарашеваNo ratings yet

- Wayne ThesisDocument32 pagesWayne ThesisyyyyoNo ratings yet

- Corpus Linguistics Research Benefits from Digital Text CollectionsDocument14 pagesCorpus Linguistics Research Benefits from Digital Text CollectionsCarmen CalvanoNo ratings yet

- Anmar Ahmed, Chapter 5Document11 pagesAnmar Ahmed, Chapter 5anmar ahmedNo ratings yet

- Colloquium of Linguistics. Johannes Gutenberg-: Theodore Marinis University of Potsdam/ZAS BerlinDocument10 pagesColloquium of Linguistics. Johannes Gutenberg-: Theodore Marinis University of Potsdam/ZAS BerlinAriol ZereNo ratings yet

- Roger AndersenDocument4 pagesRoger AndersenLovelyn MaristelaNo ratings yet

- LSA Article Explores How Context Affects Language RulesDocument22 pagesLSA Article Explores How Context Affects Language RulesOktari HendayantiNo ratings yet

- Contrastive Analysis: An Overview: Moulton's Audiolingual SlogansDocument8 pagesContrastive Analysis: An Overview: Moulton's Audiolingual Slogansstewie12No ratings yet

- Erker Guy 2012Document32 pagesErker Guy 2012Erica OliveiraNo ratings yet

- What May Words Say or What May Words NoDocument30 pagesWhat May Words Say or What May Words NoDragana Veljković StankovićNo ratings yet

- The Linguistics Journal: July 2019 Volume 13 Issue 1Document205 pagesThe Linguistics Journal: July 2019 Volume 13 Issue 1Trần Phương ThảoNo ratings yet

- Tench-Spelling in The MindDocument10 pagesTench-Spelling in The MindFrane MNo ratings yet

- Kantola, Gompel 2010Document15 pagesKantola, Gompel 2010Szu-Yu KaoNo ratings yet

- Code Switching ThesisDocument4 pagesCode Switching Thesisconnierippsiouxfalls100% (1)

- French Liaison by Native & Non Native SpeakersDocument30 pagesFrench Liaison by Native & Non Native SpeakersDan Bar TreNo ratings yet

- Fleischer Et Al 2012 - MethodDocument12 pagesFleischer Et Al 2012 - MethodRaniah Al MufarrehNo ratings yet

- Bao 2009 OneDocument29 pagesBao 2009 OneSean LowNo ratings yet

- A Lateral Theory of Phonology. What Is CVCV and Why Should It Be? Tobias Scheer, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter (2004) - 854 Pp. + Lix, ISBN 3 11 017871 0Document11 pagesA Lateral Theory of Phonology. What Is CVCV and Why Should It Be? Tobias Scheer, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter (2004) - 854 Pp. + Lix, ISBN 3 11 017871 0Lazhar HMIDINo ratings yet

- The Engl Get-Passive in Spoken DiscourseDocument18 pagesThe Engl Get-Passive in Spoken DiscourseBisera DalcheskaNo ratings yet

- On Locative Inversion and The EPP in SpaDocument9 pagesOn Locative Inversion and The EPP in SpaAnita Zas Poeta PopNo ratings yet

- One Sense Per CollocationDocument6 pagesOne Sense Per CollocationtamthientaiNo ratings yet

- Barbosa - 18 - Pro As A Minim.4 PDFDocument78 pagesBarbosa - 18 - Pro As A Minim.4 PDFBrian GravelyNo ratings yet

- 2 DESCRIPTIVE - Albright1958Document5 pages2 DESCRIPTIVE - Albright1958Christine Jane TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Vilani GrammarDocument51 pagesVilani GrammarpolobiusNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Relativity BoroditskyDocument6 pagesLinguistic Relativity Boroditskyjason_cullen100% (1)

- Is Metaphor Universal Cross Language Evidence From German and JapaneseDocument21 pagesIs Metaphor Universal Cross Language Evidence From German and JapaneseSundy LiNo ratings yet

- Interpreting Theory PDFDocument15 pagesInterpreting Theory PDFAlfonso Mora Jara100% (1)

- Volltext PDFDocument42 pagesVolltext PDFWeliyou WerdiNo ratings yet

- Testing Norwegian past tense reveals clues to SLI diagnosisDocument20 pagesTesting Norwegian past tense reveals clues to SLI diagnosisPaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Defining First Language AcquisitionDocument6 pagesDefining First Language AcquisitionJuliet ArdalesNo ratings yet

- What is InterpretingDocument10 pagesWhat is InterpretingMy Duyen HuynhNo ratings yet

- Revision of Tenses Test 10th Grade AnswersDocument5 pagesRevision of Tenses Test 10th Grade AnswersCristina IonescuNo ratings yet

- Future Simple Fun Activities Games Grammar Drills Tests - 68739Document1 pageFuture Simple Fun Activities Games Grammar Drills Tests - 68739Bianca ZobNo ratings yet

- Week 1l1 Patterns of Text DevelopmentDocument33 pagesWeek 1l1 Patterns of Text DevelopmentMarieeeeeeeeeNo ratings yet

- Psy4-Is Language Restricted To HumansDocument17 pagesPsy4-Is Language Restricted To HumansusmanNo ratings yet

- Tenses Revision: El Presente/The Present TenseDocument5 pagesTenses Revision: El Presente/The Present TenseEmanuel Nuno RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Final Exam2A - BDocument12 pagesFinal Exam2A - BGabrielaNo ratings yet

- Class 5 English2Document3 pagesClass 5 English2Ajay MishraNo ratings yet

- LitCharts My Grandmother S HouseDocument7 pagesLitCharts My Grandmother S Houseginnimalia23No ratings yet

- MasterMind 2nd Edition Level 1 Scope and SequenceDocument11 pagesMasterMind 2nd Edition Level 1 Scope and SequenceJeffery ElectroadictoNo ratings yet

- Model Paper Class 2 Nsp-Qat (Oral) Academic Development UnitDocument9 pagesModel Paper Class 2 Nsp-Qat (Oral) Academic Development UnitMalik Zahid MisanNo ratings yet

- Creative Synthesis of Modules 4 - 6Document1 pageCreative Synthesis of Modules 4 - 6Kenzel lawasNo ratings yet

- Tugas 3 Basic Reading (1) BING4102Document4 pagesTugas 3 Basic Reading (1) BING4102istiqomahNo ratings yet

- 4 5985760379857276521 unlocked-مفتوحDocument296 pages4 5985760379857276521 unlocked-مفتوحMahmoudAliNo ratings yet

- Word StructureDocument15 pagesWord StructureRiska AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Characteristics and Conventions in the Mathematical LanguageDocument89 pagesCharacteristics and Conventions in the Mathematical LanguageJerusha AnnNo ratings yet

- B.inggris - Caption (Kls 12)Document15 pagesB.inggris - Caption (Kls 12)Mella Aprilya SuharniNo ratings yet

- Using ParallelismDocument9 pagesUsing ParallelismHydzTallocoyNo ratings yet

- Super Anti AutoDocument33 pagesSuper Anti AutoVijay ChatlaniNo ratings yet

- GE 1 - Mathematics in The Modern WorldDocument15 pagesGE 1 - Mathematics in The Modern WorldKervi RiveraNo ratings yet

- Technical Writing Guidelines 6 Aug 2015Document27 pagesTechnical Writing Guidelines 6 Aug 2015Danaraj ChandrasegaranNo ratings yet

- Useful Cantonese PhrasesDocument17 pagesUseful Cantonese Phrasesmasilyn angelesNo ratings yet

- ASM404 Individual Position Paper (Syarifah Nurhaziqah)Document5 pagesASM404 Individual Position Paper (Syarifah Nurhaziqah)MaurreenNo ratings yet

- Trắc nghiệmDocument2 pagesTrắc nghiệmthomha2001No ratings yet

- 詞彙學Document3 pages詞彙學林宇仁No ratings yet

- Leading in A Crisis British English TeacherDocument10 pagesLeading in A Crisis British English TeacherHarry RadcliffeNo ratings yet

- Eng Ice Cream ManDocument13 pagesEng Ice Cream Manrafiuddin syedNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International EducationDocument9 pagesCambridge Assessment International EducationXibralNo ratings yet

- The Complete Guide To SAT Grammar Rules: 1. Faulty ModifiersDocument27 pagesThe Complete Guide To SAT Grammar Rules: 1. Faulty Modifiersray davoueNo ratings yet

- English Vocabulary Master for Advanced Learners - Listen & Learn (Proficiency Level B2-C1)From EverandEnglish Vocabulary Master for Advanced Learners - Listen & Learn (Proficiency Level B2-C1)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (7)

- English. Speaking Master (Proficiency level: Intermediate / Advanced B1-C1 – Listen & Learn)From EverandEnglish. Speaking Master (Proficiency level: Intermediate / Advanced B1-C1 – Listen & Learn)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (47)

- How to Improve English Speaking: How to Become a Confident and Fluent English SpeakerFrom EverandHow to Improve English Speaking: How to Become a Confident and Fluent English SpeakerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- English Vocabulary Master for Intermediate Learners - Listen & Learn (Proficiency Level B1-B2)From EverandEnglish Vocabulary Master for Intermediate Learners - Listen & Learn (Proficiency Level B1-B2)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (18)

- English for Everyday Activities: Picture Process DictionariesFrom EverandEnglish for Everyday Activities: Picture Process DictionariesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (16)

- English Pronunciation: Pronounce It Perfectly in 4 months Fun & EasyFrom EverandEnglish Pronunciation: Pronounce It Perfectly in 4 months Fun & EasyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (24)

- Speak Like An English Professor: A Foolproof Approach to Standard English SpeechFrom EverandSpeak Like An English Professor: A Foolproof Approach to Standard English SpeechNo ratings yet

- Phrasal Verbs for TOEFL: Hundreds of Phrasal Verbs in DialoguesFrom EverandPhrasal Verbs for TOEFL: Hundreds of Phrasal Verbs in DialoguesNo ratings yet

- Learn English: Perfect English for Hotel, Hospitality & Tourism StaffFrom EverandLearn English: Perfect English for Hotel, Hospitality & Tourism StaffRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Learn English: Ultimate Guide to Speaking Business English for Beginners (Deluxe Edition)From EverandLearn English: Ultimate Guide to Speaking Business English for Beginners (Deluxe Edition)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- 7 Shared Skills for Academic IELTS Speaking-WritingFrom Everand7 Shared Skills for Academic IELTS Speaking-WritingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Practice Makes Perfect Intermediate ESL Reading and Comprehension (EBOOK)From EverandPractice Makes Perfect Intermediate ESL Reading and Comprehension (EBOOK)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (46)

- English Vocabulary Master: 150 Phrasal Verbs (Proficiency Level: Intermediate / Advanced B2-C1 – Listen & Learn)From EverandEnglish Vocabulary Master: 150 Phrasal Verbs (Proficiency Level: Intermediate / Advanced B2-C1 – Listen & Learn)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (56)

- English Made Easy Volume One: Learning English through PicturesFrom EverandEnglish Made Easy Volume One: Learning English through PicturesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- Using English Expressions for Real Life: Stepping Stones to Fluency for Advanced ESL LearnersFrom EverandUsing English Expressions for Real Life: Stepping Stones to Fluency for Advanced ESL LearnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Black Book of Speaking Fluent English: The Quickest Way to Improve Your Spoken EnglishFrom EverandThe Black Book of Speaking Fluent English: The Quickest Way to Improve Your Spoken EnglishRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- 2500 English Sentences / Phrases - Daily Life English SentenceFrom Everand2500 English Sentences / Phrases - Daily Life English SentenceNo ratings yet

- English Vocabulary Master: Phrasal Verbs in situations (Proficiency Level: Intermediate / Advanced B2-C1 – Listen & Learn)From EverandEnglish Vocabulary Master: Phrasal Verbs in situations (Proficiency Level: Intermediate / Advanced B2-C1 – Listen & Learn)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (43)

- Verb Tenses: The Secret to Use English Tenses like a Native in 2 Weeks for Busy PeopleFrom EverandVerb Tenses: The Secret to Use English Tenses like a Native in 2 Weeks for Busy PeopleRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (11)

- English Vocabulary Master: 300 Idioms (Proficiency Level: Intermediate / Advanced B2-C1 – Listen & Learn)From EverandEnglish Vocabulary Master: 300 Idioms (Proficiency Level: Intermediate / Advanced B2-C1 – Listen & Learn)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (37)

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyFrom EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Aprenda Inglés para Principiantes con Paul Noble – Learn English for Beginners with Paul Noble, Spanish Edition: Con audio de apoyo en español y un folleto descargableFrom EverandAprenda Inglés para Principiantes con Paul Noble – Learn English for Beginners with Paul Noble, Spanish Edition: Con audio de apoyo en español y un folleto descargableNo ratings yet

- Grammar Launch Intermediate 1: Completely master 15 English grammar structures using this book and the Grammar Launch MP3s so you can reach your goal of becoming fluent in English.From EverandGrammar Launch Intermediate 1: Completely master 15 English grammar structures using this book and the Grammar Launch MP3s so you can reach your goal of becoming fluent in English.Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (5)