Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Threat To Bananas

Uploaded by

Lina khairunnisa0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesOriginal Title

A threat to bananas (2)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesA Threat To Bananas

Uploaded by

Lina khairunnisaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

A threat to bananas

In the 1950s, Central American commercial banana growers were facing

the death of their most lucrative product, the Gros Michel banana, known

as Big Mike. And now it’s happening again to Big Mike’s successor – the

Cavendish.

With its easily transported, thick-skinned and sweet-tasting fruit, the Gros

Michel banana plant dominated the plantations of Central America. United

Fruit, the main grower and exporter in South America at the time, mass-

produced its bananas in the most efficient way possible: it cloned shoots

from the stems of plants instead of growing plants from seeds, and

cultivated them in densely packed fields.

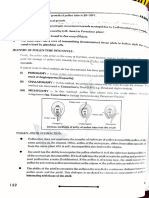

Unfortunately, these conditions are also perfect for the spread of the

fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, which attacks the plant’s roots

and prevents it from transporting water to the stem and leaves. The TR-1

strain of the fungus was resistant to crop sprays and travelled around on

boots or the tyres of trucks, slowly infecting plantations across the region.

In an attempt to escape the fungus, farmers abandoned infected fields,

flooded them and then replanted crops somewhere else, often cutting down

rainforest to do so.

Their efforts failed. So, instead, they searched for a variety of banana that

the fungus didn’t affect. They found the Cavendish, as it was called, in the

greenhouse of a British duke. It wasn’t as well suited to shipping as the

Gros Michel, but its bananas tasted good enough to keep consumers

happy. Most importantly, TR-1 didn’t seem to affect it. In a few years,

United Fruit had saved itself from bankruptcy by filling its plantations with

thousands of the new plants, copying the same monoculture growing

conditions Gros Michel had thrived in.

While the operation was a huge success for the Latin American industry,

the Cavendish banana itself is far from safe. In 2014, South East Asia,

another major banana producer, exported four million tons of Cavendish

bananas. But, in 2015, its exports had dropped by 46 per cent thanks to a

combination of another strain of the fungus, TR-4, and bad weather.

Growing practices in South East Asia haven’t helped matters. Growers

can’t always afford the expensive lab-based methods to clone plants from

shoots without spreading the disease. Also, they often aren’t strict enough

about cleaning farm equipment and quarantining infected fields. As a result,

the fungus has spread to Australia, the Middle East and Mozambique – and

Latin America, heavily dependent on its monoculture Cavendish crops,

could easily be next.

Racing against the inevitable, scientists are working on solving the problem

by genetically modifying the Cavendish with genes from TR-4-resistant

banana species. Researchers at the Queensland University of Technology

have successfully grown two kinds of modified plant which have remained

resistant for three years so far. But some experts think this is just a

sophisticated version of the same temporary solution the original

Cavendish provided. If the new bananas are planted in the same

monocultures as the Cavendish and the Gros Michel before it, the risk is

that another strain of the disease may rise up to threaten the modified

plants too.

You might also like

- Banana Extinction in 10 Years Without ActionDocument16 pagesBanana Extinction in 10 Years Without ActionNguyễn LinhNo ratings yet

- Amla PowderDocument3 pagesAmla Powderporur100% (1)

- Banana Tissue CultureDocument28 pagesBanana Tissue CultureNiks ShindeNo ratings yet

- General-Biology-2-PRELIM-EXAM - MAGBANUA STEM 11BDocument4 pagesGeneral-Biology-2-PRELIM-EXAM - MAGBANUA STEM 11BSophia MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- Readingpracticetest2 v5 451Document19 pagesReadingpracticetest2 v5 451Tú BùiNo ratings yet

- Herb properties chart for organ affinitiesDocument5 pagesHerb properties chart for organ affinitiesKirková Anastazia100% (1)

- Propagation of PlantsDocument309 pagesPropagation of PlantsMart KarmNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Test 26Document10 pagesIELTS Reading Test 26Toan Tz57% (7)

- The Manual of Plant Grafting: ExcerptDocument17 pagesThe Manual of Plant Grafting: ExcerptTimber PressNo ratings yet

- Makkar Kiranpreet Kaur Ielts Academic Readings From Past ExaDocument154 pagesMakkar Kiranpreet Kaur Ielts Academic Readings From Past ExaAamirAhmed88% (8)

- Project Practice 1Document2 pagesProject Practice 1Enad AlfayezNo ratings yet

- A Threat To BananasDocument2 pagesA Threat To BananasAsrorita SoldayNo ratings yet

- Banana Fusarium Article in BloombergDocument26 pagesBanana Fusarium Article in BloombergmiguelsuarezvallesNo ratings yet

- Pa 2 English Set A PDFDocument16 pagesPa 2 English Set A PDFVishwa AkashNo ratings yet

- C1 - Reading - LearnEnglish Reading C1 A Threat To Bananas SoalDocument4 pagesC1 - Reading - LearnEnglish Reading C1 A Threat To Bananas SoalMuhammad SyarofuddinNo ratings yet

- Before Reading: A Threat To BananasDocument4 pagesBefore Reading: A Threat To Bananasნინი მახარაძეNo ratings yet

- B.inggris Putri Aulia Pratiwi G2a220001Document6 pagesB.inggris Putri Aulia Pratiwi G2a220001Fitri AsihNo ratings yet

- The Banana PandemicDocument10 pagesThe Banana PandemicrahulthesniperNo ratings yet

- Going Bananas: The World 'S Favorite Fruit Could Disappear Forever in 10 Years ' TimeDocument5 pagesGoing Bananas: The World 'S Favorite Fruit Could Disappear Forever in 10 Years ' TimeHa Quang Huy0% (1)

- Test 1 Reading Passage 1Document11 pagesTest 1 Reading Passage 1Nguyễn Thanh TuyềnNo ratings yet

- Reading Test 1Document24 pagesReading Test 1Kiran MakkarNo ratings yet

- Reading Test 1 Passage One: Going BananasDocument24 pagesReading Test 1 Passage One: Going BananasephNo ratings yet

- Bananas Face Extinction Within a Decade Due to DiseaseDocument6 pagesBananas Face Extinction Within a Decade Due to DiseaseTú UyênNo ratings yet

- Fusarium Wilt of Banana: Fusarium Oxysporum F.sp. CubenseDocument2 pagesFusarium Wilt of Banana: Fusarium Oxysporum F.sp. CubenseLawrence Lim Ah KowNo ratings yet

- Banana's Genetic Uniformity Leaves it Vulnerable to DiseasesDocument3 pagesBanana's Genetic Uniformity Leaves it Vulnerable to DiseasesLinh TranNo ratings yet

- Recent Actual Reading Test 2ehegDocument55 pagesRecent Actual Reading Test 2ehegMarufNo ratings yet

- Reading Mock TestDocument11 pagesReading Mock Testbeyond belief100% (1)

- New Reading Going BananasDocument8 pagesNew Reading Going Bananasaaradhya instituteNo ratings yet

- Fusarium Wilt in 'Cavendish' Banana Caused by Foc TR4: A Threat To Philippine Banana IndustryDocument17 pagesFusarium Wilt in 'Cavendish' Banana Caused by Foc TR4: A Threat To Philippine Banana IndustryCecirly Gonzales PuigNo ratings yet

- Going BananasDocument8 pagesGoing BananasfitriNo ratings yet

- Bananas Face Extinction in 10 YearsDocument6 pagesBananas Face Extinction in 10 YearsNguyễn Mai UyênNo ratings yet

- Pest ManagementDocument10 pagesPest ManagementJohn Fetiza ObispadoNo ratings yet

- Banana Case Study Guide Number 4 PDFDocument8 pagesBanana Case Study Guide Number 4 PDFAnonymous ZfHyReKz8ENo ratings yet

- Technical Manual: Prevention and Diagnostic of Fusarium Wilt (Panama Disease) of Banana Caused by Race 4 (TR4)Document74 pagesTechnical Manual: Prevention and Diagnostic of Fusarium Wilt (Panama Disease) of Banana Caused by Race 4 (TR4)Alaa OudahNo ratings yet

- Ielts Test ReadingDocument11 pagesIelts Test ReadingßläcklìsètèdTȜèNo ratings yet

- Going Bananas: Checkboxes & Related Question TypesDocument7 pagesGoing Bananas: Checkboxes & Related Question TypesTUTOR IELTSNo ratings yet

- Peter Angelo GDocument7 pagesPeter Angelo GNexon Rey SantisoNo ratings yet

- Ieltsfever Academic Reading Practice Test 37 PDFDocument13 pagesIeltsfever Academic Reading Practice Test 37 PDFANo ratings yet

- IPM strategies for cassava pests and diseasesDocument31 pagesIPM strategies for cassava pests and diseasesKimi DorsNo ratings yet

- Cavendish banana - the most commonly sold banana variety worldwideDocument18 pagesCavendish banana - the most commonly sold banana variety worldwideMuhammad ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Randy C Ploetz - Diseases of Tropical Fruit Crops-CABI (2003) - 96-148Document53 pagesRandy C Ploetz - Diseases of Tropical Fruit Crops-CABI (2003) - 96-148Kres DahanaNo ratings yet

- Inside The Quest To Save The Banana From Extinction 1Document1 pageInside The Quest To Save The Banana From Extinction 1fredwineNo ratings yet

- MANAGING RICE BLACKBUG THROUGH BIOLOGICAL CONTROLDocument8 pagesMANAGING RICE BLACKBUG THROUGH BIOLOGICAL CONTROLJohnniel Cabanes CabalarNo ratings yet

- Ploetz 2015 Fusarium Wilt in Bananas PhytopathologyDocument10 pagesPloetz 2015 Fusarium Wilt in Bananas PhytopathologyGabriel ViniciusNo ratings yet

- Conventional Breeding of BananasDocument12 pagesConventional Breeding of BananasCédric KENDINE VEPOWONo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 ASSIGNMENTDocument4 pagesLesson 1 ASSIGNMENTAbdul IliyazNo ratings yet

- Cassava Is A Perennial Shrub With A Bulky Storage Root Published in Science DirectDocument12 pagesCassava Is A Perennial Shrub With A Bulky Storage Root Published in Science DirectLSPRO LAMPUNGNo ratings yet

- Crop Disease Management Black RotDocument10 pagesCrop Disease Management Black RotJiri MutamboNo ratings yet

- Plants 11 01804Document21 pagesPlants 11 01804Tomás Afonso CavacoNo ratings yet

- Emily Makowski, "Mass Appeal: Saving The World's Bananas From A Devastating Fungus"Document22 pagesEmily Makowski, "Mass Appeal: Saving The World's Bananas From A Devastating Fungus"MIT Comparative Media Studies/WritingNo ratings yet

- 10969-NARI Guyana Culture Et Post-Récolte de Manioc (Angl)Document17 pages10969-NARI Guyana Culture Et Post-Récolte de Manioc (Angl)Madam CashNo ratings yet

- JeffersonDocument5 pagesJeffersonSsenyondo JeffersonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document4 pagesChapter 1Cian LorenceNo ratings yet

- Churchill 2011Document23 pagesChurchill 2011gusti darmawanNo ratings yet

- PAT-101-Fundamentals of Plant PathologyDocument65 pagesPAT-101-Fundamentals of Plant PathologyShivansh GurjarNo ratings yet

- Banana Crisis WorksheetDocument2 pagesBanana Crisis Worksheetapi-327823961No ratings yet

- Literature Review On BreadfruitDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Breadfruitgw131ads100% (1)

- ARABLE CULTIVATION Cassava ProductionDocument6 pagesARABLE CULTIVATION Cassava Productionojo bamideleNo ratings yet

- DR. RICARDO M. LANTICAN's Pioneering Scientific Works in Plant Breeding Have HadDocument1 pageDR. RICARDO M. LANTICAN's Pioneering Scientific Works in Plant Breeding Have HadJacobNo ratings yet

- Organic Control of Whit Mold On SoybeansDocument4 pagesOrganic Control of Whit Mold On Soybeansvas_liviuNo ratings yet

- C. CoffeanumDocument37 pagesC. CoffeanumMiranda M Guzmán MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Melon CultureDocument49 pagesMelon CultureToan DoVanNo ratings yet

- Managing Pitaya Pests and DiseasesDocument14 pagesManaging Pitaya Pests and DiseasesBarbara Fábio Melo CruvinelNo ratings yet

- The Library of Work and Play: Gardening and Farming. by Shaw, Ellen EddyDocument170 pagesThe Library of Work and Play: Gardening and Farming. by Shaw, Ellen EddyGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Nitrogen Foliar Feeding: Has AdvantagesDocument4 pagesNitrogen Foliar Feeding: Has Advantageszikra arahmanNo ratings yet

- Tugas English ApasihDocument10 pagesTugas English Apasihandi carlaNo ratings yet

- @atersne (: A Room of Their Own The Fungus Among UsDocument6 pages@atersne (: A Room of Their Own The Fungus Among UsGreenspace, The Cambria Land TrustNo ratings yet

- Market: Classification: InternalDocument4 pagesMarket: Classification: InternalTruc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Is AmazingDocument6 pagesBiodiversity Is AmazingNurlaela PujiantiNo ratings yet

- DLL - Epp 6 - q1 - Agri - w3Document4 pagesDLL - Epp 6 - q1 - Agri - w3Bimbo CuyangoanNo ratings yet

- Control of Brachiaria Arrecta in A Wet Environment - 2Document7 pagesControl of Brachiaria Arrecta in A Wet Environment - 2Nilamdeen Mohamed ZamilNo ratings yet

- Adiciones A Chrysobalanaceae PDFDocument270 pagesAdiciones A Chrysobalanaceae PDFBrandon CruzNo ratings yet

- Erwinia Carotovora Subsp Carotovora PDFDocument2 pagesErwinia Carotovora Subsp Carotovora PDFCharlesNo ratings yet

- Technical Name and Features of Major InsecticidesDocument18 pagesTechnical Name and Features of Major Insecticidesvishal37256No ratings yet

- Periodical Test - TLE-AGRI 6 - Q1Document9 pagesPeriodical Test - TLE-AGRI 6 - Q1John Marc CabralNo ratings yet

- Okra (Abelmoschus Esculentus L.) Yield Influenced by Albizia Leaf Mould and Banana Peel With Half Dosage of NP Chemical FertilizersDocument10 pagesOkra (Abelmoschus Esculentus L.) Yield Influenced by Albizia Leaf Mould and Banana Peel With Half Dosage of NP Chemical FertilizersMin SyubieNo ratings yet

- V6I109 3 February 2021Document9 pagesV6I109 3 February 2021Harrizul RivaiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Sexual StrategiesDocument130 pagesChapter 3 - Sexual StrategiesHenrique ScreminNo ratings yet

- Makahiya Extract as Natural Insecticide for Stem BorersDocument17 pagesMakahiya Extract as Natural Insecticide for Stem BorersKristine Delos Santos100% (1)

- Advances in botanical prospecting methodsDocument12 pagesAdvances in botanical prospecting methodsNehaNo ratings yet

- Cucumber Production Guideline 2014 Starke AyresDocument4 pagesCucumber Production Guideline 2014 Starke AyresHerbert KatanhaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Seaweeds Sargasssum As Organic Fertilizer in The Growth Performance of EggplantDocument7 pagesEffect of Seaweeds Sargasssum As Organic Fertilizer in The Growth Performance of EggplantKaedi Lynette DoctoleroNo ratings yet

- Lab Rep 4Document27 pagesLab Rep 4Reign RosadaNo ratings yet

- Seed Plants Gymnosperms and Angiosperms 1 PDFDocument17 pagesSeed Plants Gymnosperms and Angiosperms 1 PDFBharatiyaNaari67% (3)

- CBSE Class 11 Biology Chapter 6 Anatomy of Flowering Plants Revision NotesDocument72 pagesCBSE Class 11 Biology Chapter 6 Anatomy of Flowering Plants Revision Noteschakrabortytrisha.2006No ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Oct 31, 2023Document25 pagesAdobe Scan Oct 31, 2023amanazim404No ratings yet

- Nutrient Deficiencies and Application Injuries in Field CropsDocument12 pagesNutrient Deficiencies and Application Injuries in Field Cropskenfack sergeNo ratings yet

- Euterpe Precatoria PDFDocument2 pagesEuterpe Precatoria PDFJenniferNo ratings yet