Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Constructionism: Social Constructionism Is A Theory of Knowledge That Holds That Characteristics

Uploaded by

aneela khan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views2 pagesOriginal Title

Document (7)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views2 pagesSocial Constructionism: Social Constructionism Is A Theory of Knowledge That Holds That Characteristics

Uploaded by

aneela khanCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Social Constructionism

Social constructionism is a theory of knowledge that holds that characteristics

typically thought to be immutable and solely biological—such as gender, race, class,

ability, and sexuality—are products of human definition and interpretation shaped by

cultural and historical contexts (Subramaniam 2010). As such, social constructionism

highlights the ways in which cultural categories—like “men,” “women,” “black,”

“white”—are concepts created, changed, and reproduced through historical processes

within institutions and culture. We do not mean to say that bodily variation among

individuals does not exist, but that we construct categories based on certain bodily

features, we attach meanings to these categories, and then we place people into the

categories by considering their bodies or bodily aspects. For example, by the one-

drop rule (see also page 35), regardless of their appearance, individuals with any

African ancestor are considered black. In contrast, racial conceptualization and thus

racial categories are different in Brazil, where many individuals with African ancestry

are considered to be white. This shows how identity categories are not based on strict

biological characteristics, but on the social perceptions and meanings that are

assumed. Categories are not “natural” or fixed and the boundaries around them are

always shifting—they are contested and redefined in different historical periods and

across different societies. Therefore , the social constructionist perspective is

concerned with the meaning created through defining and categorizing groups of

people, experience, and reality in cultural contexts.

Social constructionist approaches to understanding the world challenge the essentialist

or biological determinist understandings that typically underpin the “common sense”

ways in which we think about race, gender, and sexuality. Essentialism is the idea

that the characteristics of persons or groups are significantly influenced by biological

factors, and are therefore largely similar in all human cultures and historical periods.

A key assumption of essentialism is that “a given truth is a necessary natural part of

the individual and object in question” (Gordon and Abbott 2002). In other words, an

essentialist understanding of sexuality would argue that not only do all people have a

sexual orientation, but that an individual’s sexual orientation does not vary across

time or place. In this example, “sexual orientation” is a given “truth” to individuals—

it is thought to be inherent, biologically determined, and essential to their being.

Essentialism typically relies on a biological determinist theory of identity. Biological

determinism can be defined as a general theory, which holds that a group’s biological

or genetic makeup shapes its social, political, and economic destiny (Subramaniam

2014). For example, “sex” is typically thought to be a biological “fact,” where bodies

are classified into two categories, male and female. Bodies in these categories are

assumed to have “sex”-distinct chromosomes, reproductive systems, hormones, and

sex characteristics. However, “sex” has been defined in many different ways,

depending on the context within which it is defined. For example, feminist law

professor Julie Greenberg (2002) writes that in the late 19th century and early 20th

century, “when reproductive function was considered one of a woman’s essential

characteristics, the medical community decided that the presence or absence of

ovaries was the ultimate criterion of sex” (Greenberg 2002: 113). Thus, sexual

difference was produced through the heteronormative assumption that women are

defined by their ability to have children. Instead of assigning sex based on the

presence or absence of ovaries, medical practitioners in the contemporary US

typically assign sex based on the appearance of genitalia.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Psychology of LeadershipDocument59 pagesPsychology of LeadershipCOT Management Training Insitute100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Thomas Paine Social and Political ThoughtDocument272 pagesThomas Paine Social and Political Thoughtaliixa100% (2)

- MmpiDocument19 pagesMmpianeela khanNo ratings yet

- The Second SexDocument25 pagesThe Second Sexhamdi1986100% (1)

- Differential Reinforcement TheoryDocument13 pagesDifferential Reinforcement TheoryLawrence Amans Ballicud100% (1)

- Relevance of Plato's Philosophy TodayDocument5 pagesRelevance of Plato's Philosophy TodayLjubomir100% (1)

- Toulmin ModelDocument3 pagesToulmin ModelJohnConnorNo ratings yet

- DeconstructionDocument15 pagesDeconstructionAmine SalimNo ratings yet

- PanopticismDocument2 pagesPanopticismplanet2o100% (1)

- Theories Related To The Learner's DevelopmentDocument30 pagesTheories Related To The Learner's DevelopmentMichael Moreno83% (36)

- An Introduction To MetametaphysicsDocument268 pagesAn Introduction To MetametaphysicsφιλοσοφίαNo ratings yet

- Report Aneela MSDocument1 pageReport Aneela MSaneela khanNo ratings yet

- Job Application Form For LecturerDocument3 pagesJob Application Form For Lectureraneela khanNo ratings yet

- Cover LetterDocument1 pageCover Letteraneela khanNo ratings yet

- Name of Student1Document2 pagesName of Student1aneela khanNo ratings yet

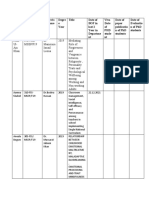

- Courses Outline PHD 2022-23Document3 pagesCourses Outline PHD 2022-23aneela khanNo ratings yet

- Ist Lecture CommunicationDocument19 pagesIst Lecture Communicationaneela khanNo ratings yet

- Clinical PsychologyDocument2 pagesClinical Psychologyaneela khanNo ratings yet

- Inclusion 1Document1 pageInclusion 1aneela khanNo ratings yet

- Wa0006.Document2 pagesWa0006.aneela khanNo ratings yet

- Victorian CompromiseDocument2 pagesVictorian Compromiseararatime100% (1)

- Department of Education: Region Iv - A Calabarzon Division of Calamba CityDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Region Iv - A Calabarzon Division of Calamba CityEditha BalolongNo ratings yet

- Uts Module 2Document6 pagesUts Module 2Alexis OngNo ratings yet

- Social Contract TheoryDocument11 pagesSocial Contract TheoryFida Fathima S 34No ratings yet

- Ethics Midterm ExamDocument2 pagesEthics Midterm ExamKimberly MilanteNo ratings yet

- Plant-2004-Journal of Religious EthicsDocument28 pagesPlant-2004-Journal of Religious EthicsSabinaAvramNo ratings yet

- Stuvia 355912 Edc1015 Theoretic Frameworks in Education Exam PrepDocument44 pagesStuvia 355912 Edc1015 Theoretic Frameworks in Education Exam PrepfdjNo ratings yet

- Kti Problem SolvingDocument3 pagesKti Problem SolvingSiti Nur AlifahNo ratings yet

- Stanford University Guide To Hegel's Dialectics PDFDocument35 pagesStanford University Guide To Hegel's Dialectics PDFUriel GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- TOS 3rdqtr - Science8. v1Document11 pagesTOS 3rdqtr - Science8. v1Berith Grace Magcalas-GallardoNo ratings yet

- Critical ThinkingDocument7 pagesCritical Thinkingrudrakshvijayvargiya4000No ratings yet

- Pad120 Summary (1,2,3)Document3 pagesPad120 Summary (1,2,3)AM110 2C Muhammad Iman HakimNo ratings yet

- Universal Religion of Swami VivekanandaDocument7 pagesUniversal Religion of Swami VivekanandaShruti SharmaNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence AssignmentDocument7 pagesJurisprudence AssignmentTimore Francis0% (2)

- Epoche (Suspension of Belief)Document2 pagesEpoche (Suspension of Belief)John UebersaxNo ratings yet

- Emotional Bank AccountDocument2 pagesEmotional Bank AccountarkuttyNo ratings yet

- H.P National Law University, Shimla: Assignment of "Legal Methodology" Topic: Dimension of Justice: An OverviewDocument12 pagesH.P National Law University, Shimla: Assignment of "Legal Methodology" Topic: Dimension of Justice: An OverviewKushagra SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- JusticeDocument2 pagesJusticepritamNo ratings yet

- Hermeneutics - Qualitative Methods in Organizational ResearchDocument12 pagesHermeneutics - Qualitative Methods in Organizational ResearchRenata HorvatekNo ratings yet

- G.A. Cohen - Is Socialism Inseperable From Common Ownership (1995) PDFDocument4 pagesG.A. Cohen - Is Socialism Inseperable From Common Ownership (1995) PDFMatheus GarciaNo ratings yet