Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mapping the Terrain of Public Art Practices and Their Impact

Uploaded by

luis_rhOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mapping the Terrain of Public Art Practices and Their Impact

Uploaded by

luis_rhCopyright:

Available Formats

Mapping the Terrain, Again

Author(s): Stephanie Smith

Source: Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry , Issue 27 (Summer 2011), pp. 67-

76

Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Central Saint Martins College

of Art and Design, University of the Arts London

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/661612

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press and Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, University

of the Arts London are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Poster for Suzanne

Lacy, ‘City Sites:

Artists and Urban

Strategies' lecture

series, 1989,

Oakland, CA.

Design by Michael

Manwaring.

Courtesy the artist

66 | Afterall

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Mapping the Terrain,

Again

— Stephanie Smith

A group of artists and writers, curators and administrators, activists and assorted citizens

assemble on a November evening, packing a large room inside a museum in the US. Some

wear name tags. They sit in tight orderly rows, chairs arranged in two groups so that they

face each other across a narrow aisle. There is no stage, no focal point, no obvious delinea-

tion between expert and audience. Instead, when the event begins, one individual stands

up amidst the crowd and talks for three minutes. As he sits, another stands across the room,

also talking for three minutes. Heads twist and bodies turn to focus on her remarks. A third

rises. It goes on, as thirty speakers — some analytical, some passionate, some engaging —

use their allotted time to comment on the intersections of art, activism, politics and publics.

This beginning is choreographed — the physical arrangement, the placement and ordering

of speakers, the scope of aesthetic territory addressed, the intentional blurring of all kinds

of lines — and then the event relaxes into a more informal discussion.

This structure probably sounds familiar. The event might have been a discursive

extension of an exhibition, or part of a progressive museum education programme.

Perhaps it was a session within the latest Creative Time summit on public practice,

a gathering instigated by the artists and writers of the Midwest Radical Culture Corridor

or a manifestation of West Coast social

Stephanie Smith looks back at Suzanne practice like the Open Engagement

conference held last summer in Oregon. 1

Lacy’s Mapping the Terrain: New Genre In other words, because of its format and

Public Art, and the events leading up to subject matter, the event could fit easily

its publication, in order to suggest new within recent North American iterations

of a global conversation about the social

models for understanding the complexities functions; ethical and aesthetic intentions;

of participation in contemporary art. and public responsibilities of art, creative

workers and cultural institutions. But

in fact it took place twenty years ago, in November 1991, as one link in a chain of activities

instigated by artist, writer and educator Suzanne Lacy, and orchestrated in collaboration

with others — a chain that eventually yielded, in 1995, the landmark book Mapping the

Terrain: New Genre Public Art. 2

Twenty years after that gathering and sixteen years after the book’s publication,

Mapping the Terrain remains essential to a critical consideration of what truly public

art might be. 3 The ‘new genre’ moniker that the subtitle of the book proposed failed to gain

1 In 2009, the New York-based Creative Time extended its work as a commissioner of public

projects and events by instigating an annual programme, the ‘Creative Time Summit: Revolutions

in Public Practice’. This event, curated by Nato Thompson, gathers practitioners and theorists

from around the world. See http://creativetime.org/programs/archive/2010/summit/WP/

(last accessed on 21 March 2011). In 2010, the Social Practice MFA program at Portland State

University, led by artist Harrell Fletcher, launched an annual gathering, ‘Open Engagement’,

a larger and looser multi-day event. See http://openengagement.info/conference-information

(last accessed on 21 March 2011). The Midwest Radical Culture Corridor is a rubric used since 2007

by a group of writers and artists based across the central US to organise field trips, discussions

and collaborative projects. See http://www.midwestradicalculturecorridor.net/ (last accessed

on 21 March 2011).

2 See Suzanne Lacy (ed.), Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, Seattle: Bay Press, 1995. The event

is mentioned in the preface; this description is extrapolated from video documentation of the event

from Lacy’s archive and from conversations between the author and Lacy on 19 January and 2 February

2011. The author would like to thank Lacy for her generosity in sharing ideas and information over

many years of conversation, and for access to her archive in spring 2010.

3 Mapping the Terrain forms part of a constellation of books and projects about public art published in

the US around that time, including an anthology edited by Nina Felshin called But Is It Art?: The Spirit

of Art as Activism (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995) and the catalogue for Mary Jane Jacob’s massive public art

exhibition ‘Culture in Action’ (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995), two years after the exhibition took place

in Chicago.

Contexts: Mapping the Terrain | 67

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

wide usage, but the book nonetheless propelled awareness of and discussion about several

loosely affiliated strands of art-making, mostly in the US, that took place largely outside

institutional sites and were intentionally situated at the intersection of ethics and

aesthetics. The works usually presupposed an activist potential for art, addressed social

and political issues — directly or obliquely — and took up process-based forms that were

collectively produced within specific places and communities. While these modes of

making drew on longer strands of creative production that extend at least back into

the 1960s, they coalesced and became clearly visible in the US in the late 1980s and

early 90s, as a vibrant if slippery-edged zone of activity. Mapping the Terrain helped

define and disseminate these practices, and proposed some important early framings

of why and how they might matter.

All well enough. But it is worth looking at Mapping the Terrain again, right now,

not only to understand its impact in its time and subsequently, but also because it contains

tools that might usefully inform our thinking about things happening in our time,

especially in relation to the rampant current interest in defining, critiquing, promoting

and/or theorising overlapping categories of critical art, public art practice, collective

work and social practice. I will return to this, but first want to test out a different frame:

Mapping the Terrain might also be positioned as an extension of Suzanne Lacy’s art

— as a book about new genre public art that is, itself, a manifestation of the practice.

Please take what follows as a thought experiment rather than a strong claim, for such

a reading has obvious limitations, but I hope it might open productive lines of thought

about the book’s specific contributions, its particular blind spots and its ongoing

relevance.

Born in 1945, Suzanne Lacy grew up in a working-class family in California,

studied psychology and worked briefly as a community organiser during the late 1960s.

She shifted her focus to art in the early 1970s, studying first with Judy Chicago at Fresno

State College and then with both Chicago and Allan Kaprow at the newly founded

California Institute of the Arts. Lacy played a catalytic role within a group of creative

women in Los Angeles who built a community centred on the Feminist Studio Workshop

and the Women’s Building, the now-

Incredibly for a project taking legendary studio-collective-school-gallery

founded in 1973 by Chicago, Sheila de

place before the advent of the Bretteville and Arlene Raven. By the

internet, Lacy’s work directly late 1970s, Lacy had begun to formulate

engaged about 2,000 women what became a trademark approach:

through 200 dinners that multilayered collaborative projects

took place across Africa, that addressed specific social issues

Asia, Europe and North and particular communities through

combinations of performance, display,

and South America during community organising, public outreach

a 24-hour period. and media intervention. Most famously,

two projects from 1977 brought visibility

to violence against women in Los Angeles —Three Weeks in May and In Mourning

and in Rage, the latter in collaboration with artist Leslie Labowitz. Labowitz and Lacy

folded these and several later projects into an initiative they called Ariadne: A Social

Art Network. This framework encompassed their own projects but was also meant to

foment actions by others — for instance they cowrote a kind of pragmatic and conceptual

toolkit targeted at others who might ‘join us in the growing movement of feminist culture

workers and media interventionists’. 4

A lesser-known project from this period, The International Dinner Party (1979),

reinforces this point while bringing a key new element — conviviality — into the mix.

Convivial gatherings are, of course, crucial glue within any community, and in Los Angeles

in the 1970s — as in feminist circles around the world — meals were also intentionally used

as occasions to bring women together, strengthen personal bonds and hone political aims.

Lacy extended this sensibility in this artwork, for which she used her organisational skills

4 S. Lacy and Leslie Labowitz, ‘Feminist Artists: Developing a Media Strategy for the Movement’,

in S. Lacy, Leaving Art: Writings on Performance, Politics, and Publics, 1974—2007, Durham, NC:

Duke University Press, 2010, p.85.

68 | Afterall

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and connections within global feminist-activist circles to invite thousands of women from

around the world to stage dinners, each as a tribute to a particular woman. The project

was in part a tribute to Lacy’s mentor Judy Chicago, and was initiated on the occasion

of the West Coast debut of Chicago’s now-iconic installation The Dinner Party (1974—79)

at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Incredibly for a project taking

place before the advent of the internet, Lacy’s work directly engaged about 2,000 women

through 200 dinners that took place across Africa, Asia, Europe and North and South

America during a 24-hour period. Participants sent telegrams to SFMOMA, and Lacy

created a combination of performance and display in which she marked the dinner

locations on a giant wall-map and placed the telegrams in binders. Later, many participants

sent photographs, letters and other material documenting their meals, some of which

Lacy culled, edited and arranged into new two-dimensional pieces — sometimes, for

instance, by handwriting descriptive text across their imagery. Four aspects of the project

are important to flag in relation to Mapping the Terrain: Lacy’s role as a convener;

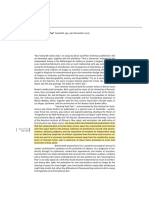

Image from Suzanne the project’s ambitious scope; the establishment of parameters that intentionally combine

Lacy, ‘Mapping experience and discourse; and the creation of a framework to ‘report out’, so that a wider

the Terrain'

public conference, public might have access to ideas generated in a private context (here, notably, through

November 1991, what one might see as an editorial process of gathering, culling and arranging materials

Napa, CA, showing to later disseminate the results).

Patricia Phillips.

Courtesy the artist A decade later, Lacy began to formulate a kind of meta-project, centred on

bringing together colleagues who shared her interest in socially-engaged, community-

and process-based forms of public art (which she referred to as ‘social art’ in a

continuation of the Ariadne language). With this new project, she focused on an art

world community rather than a specifically feminist network, and began a multi-tiered

collaborative process of assembling peers who cared about these then-new forms of

public art. The objective was to collectively develop analytical tools and frameworks

that could help shape a wider conversation about the relevance and potential impact

of this type of work.

The series of lectures ‘City Sites: Artists and Urban Strategies’, held in 1989, was the

first manifestation of this idea. Making strategic use of her new position as Dean of Fine

Arts at the California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) in Oakland, California, Lacy

secured college support to launch ‘City Sites’ as an experimental series of site-specific

Contexts: Mapping the Terrain | 69

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

lectures that brought together ten artists whose practices she felt fit this rubric. 5 In a 1990

interview Lacy noted that she had been motivated

to encourage critics to look at this kind of work to see if we can develop a language

for describing it that goes beyond performance, Conceptual art, painting or murals.

People are becoming more and more interested in social art. It’s my belief that there

is now a group of artists who have been working for ten-plus years, and who have

— out of the political necessity of their work — created a fairly sophisticated

structural language and set of strategies. 6

Each artist presented a talk about his or her work at a site connected in some way to his or

her topic, for audiences that Lacy described as ‘mixed’ through their blending of art world

and other kinds of communities. John Malpede of the activist art and theatre group Los

Angeles Poverty Department, for instance, spoke at a homeless shelter, while Adrian Piper

spoke about racial stereotypes at a nightclub. Analysis of the lectures’ intentions, outcomes Image from Suzanne

and implications is beyond the scope of this essay, but note again Lacy’s role as a convener; Lacy, ‘Mapping

the Terrain' retreat,

the combination of shared experience and discourse; and the creation of a framework November 1991,

through which to shape a larger conversation. Napa, CA. Pictured,

The meta-project continued two years later when Lacy orchestrated ‘Mapping the from left to right:

Jennifer Dowley,

Terrain: New Genre Public Art’, a two-part affair that combined public performance and Mierle Laderman

closed discussion — a format now familiar from biennial platforms and aesthetic caucuses Ukeles, Suzanne

but uncommon at the time. 7 It began with the choreographed public event described at Lacy, Leopoldo Maler,

Patricia Phillips

and Mary Jane Jacob.

5 Participants included Judy Baca, Helen and Newton Harrison, Lynn Hershman, Marie Johnson-Calloway, Courtesy the artist

Allan Kaprow, Suzanne Lacy, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, John Malpede and Adrian Piper. See the preface

to S. Lacy (ed.), Mapping the Terrain, op. cit., pp.11—13. See also local newspaper coverage that situates

‘City Sites’ within the larger context of civic and cultural development strategies in Oakland: Jean

Field, ‘Art for Oakland’s Sake’, San Francisco Bay Guardian, 22 February 1989, pp.17 and 20; and Janice

Ross, ‘Adventures in Oakland: Public Art Tackles Some Public Issues’, The Tribune Calendar, 26 February

1989, pp.5 and 24.

6 Moira Roth, ‘Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy, March 16, 24, and September 27, 1990’,

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

7 The event was directed by Lacy, co-sponsored by CCAC and the Headlands Center for the Arts and held

at SFMOMA, where it was arranged through the education department (which remains a fairly common

channel through which socially engaged practices enter museums). It was funded by the museum,

CCAC, various foundations and the National Endowment for the Arts. See S. Lacy (ed.), Mapping the

Terrain, op. cit., p.14.

70 | Afterall

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the beginning of this essay, which simultaneously generated an aesthetic experience and

initiated a process of analysis. Those thirty speakers performed for each other, as well

as the audience mixed in with them, by using their allotted minutes to mark the outlines

of the terrain each cared most about — that is, the place from which they spoke. It seems

to have been a fairly efficient means to begin to build a shared understanding of the range

of practices and stances under discussion, a way of marking the outside edges of the

topic and glossing the state of the practice while also clarifying specific territories of

interest. The participants and a few other artists, administrators and writers then moved

into a closed-session multi-day retreat in Napa Valley, where they built on those initial

performative mini-speeches. Over several days they moved between small-group

discussions, larger sessions and convivial experiences, with the aim of coming to terms

with these new forms of public art. 8

The book that grew out of these activities, Mapping the Terrain, includes three types

of writing: Lacy’s introduction, which touches on this backstory and is liberally peppered

with quotes from both the public and

The list of artists reveals the private parts of the gathering; essays

that provide critical frameworks produced

shifting terms of conversation

by participants (with the addition of

about public practice. Some of Guillermo Gómez-Peña); and an illustrated

the artists featured in Mapping compendium of artists and projects

the Terrain would probably that provides concrete examples of

not be framed as ‘public’ or the practices discussed in the essays. 9

‘socially engaged’ artists today. In the end, the extended process that

generated these texts wasn’t so different

from that deployed in Ariadne or The International Dinner Party: frameworks were

created in which people could generate experience and discourses around a topic, and

then disseminate results that might inspire changes across a wider field. That linkage was

apparent to Lacy at the time: in 1990 she described Ariadne as

a context out of which we would generate our works, we would support and advise

other people in doing works and we would write articles on what we were doing.

It’s similar to what I’m doing with ‘City Sites’. It’s a way to create a context which

generates theory and practice. 10

So, what of the book itself? The texts are uneven, and some have aged more gracefully

than others. Jeff Kelley’s discussion of ‘place’ versus ‘site’ in architecturally-based

projects still feels useful, for instance. But those parts of the book that don’t hold up

as well still offer helpful insights into where things were then and how they have changed.

The compendium is invaluable in this regard, for the list of artists reveals the shifting

of the terms of conversation about public practice. Some of the artists featured in the

compendium (including some ‘City Sites’ and conference participants) would probably

not be framed as ‘public’ or ‘socially engaged’ artists today — Ann Hamilton comes

to mind, for instance. Some texts feel antiquated because wider conversations have

changed. At the time, new genre public art was perhaps identifiable less by what it was

than by what it was not — no ‘plop art’ plaza sculptures, no cannons in parks. But the need

to define new forms in opposition to traditional modes of sculpture is no longer urgent and

therefore no longer part of today’s discourse — which indicates the degree to which these

practices have become naturalised. Finally, the group of participants, with its emphasis on

the US, feels quite constrained now. One couldn’t imagine in 1991 the current extent and

8 Speakers included Juana Alicia, Judy Baca, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Mel Chin, Estella Conwill

Májozo, Houston Conwill, Jennifer Dowley, Patricia Fuller, Suzi Gablik, Anna Halprin, Ann Hamilton,

Jo Hansen, Helen Harrison, Lynn Hershman, Walter Hood, Mary Jane Jacob, Chris Johnson, Allan

Kaprow, Suzanne Lacy, Hung Liu, Alf Löhr, Yolanda Lopez, Lucy Lippard, Leopoldo Mahler, Jill Manton,

David Mendoza, Richard Misrach, Peter Pennekamp, Patricia Phillips, Lynn Sowder, Mierle Laderman

Ukeles and Carlos Villa. Others joined the closed portion of the session. The book essays were authored

by a smaller group: Baca, Conwill Májozo, Gablik, Jacob, Jeff Kelley, Kaprow, Lacy, Lippard and Phillips

— and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, the only essayist who did not attend the gathering. Susan Leibovitz

Steinman produced the compendium.

9 The parameters for inclusion were established through group discussion. See Lacy’s introduction

in S. Lacy (ed.), Mapping the Terrain, op. cit., pp.189—92.

10 M. Roth, ‘Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy’, op. cit.

Contexts: Mapping the Terrain | 71

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

pervasiveness of globalisation nor any of the other myriad and endlessly arguable factors

that have since come into play — the existence of the internet, shifts in government funding,

changes in institutional practice and pedagogical strategy, 11 the spread of biennials, new

generational temperaments and many others. Any or all of these may have propelled the

current global proliferation of aesthetic practices, factions, splinters and new entities that

grew out of the terrain mapped by Lacy and her cohorts twenty years ago.

Which brings me back to the question of Mapping the Terrain’s relevance to recent

criticism. Despite the decades that separate now from then — with attendant shifts in

aesthetics, politics and practice — some parts of Mapping remain bracingly relevant. 12

Lacy’s own essay, for instance, offers cool analysis that might cut through some of the

rhetoric that has swirled around recent debates about ‘the social turn’ in 1990s and 2000s

art. Take, for instance, a famously heated exchange between critics Claire Bishop and

Grant Kester that played out on the pages of Artforum a few years back. 13 Bishop argues

that champions of socially-based work often sidestep any assessment of a particular

project’s aesthetic potency or conceptual nuance, privileging instead its activist intentions

and degree of collaborative co-creation — which she describes as an ‘ethics of authorial

renunciation’. Kester then takes Bishop to task for a range of issues including conflating

social and socially-based ways of working, and for drawing too hard a line between

aesthetics and activism. Lacy’s primary essay in Mapping explores adjacent territory.

In it, she advocates for more subtle and complex criticism and offers analytic

tools and frames to that end, including a diagram that I still find enormously helpful.

This visual model succinctly delineates a wider range than the usual dyad of ‘artist’ and

‘audience’. Based on varied points of connection to a work’s production and reception,

these circles begin with the person most responsible for the work — the artist — at the

centre, and then move out through collaborators and eventually on to ‘the audience

of myth and memory’. These categories are fluid: individuals might move through each

of the circles, which, Lacy argues, offer complementary sites for critical analysis beyond

the traditional moment of aesthetic interaction in which a person encounters a ‘finished’

product (be it a painting, a sculpture or a performance). If we think of Mapping the

Terrain as an artwork, for instance, we might consider that first circle of origination

and responsibility as a rather tight one defined by Lacy’s creative vision for this project,

based in her particular aesthetic and intellectual approaches and strongly influenced

by her feminist organisational methods. Then we might consider how the project was

presented for and experienced by those who intersected with early manifestations of

Mapping the Terrain, either as collaborators and co-creators or as audience members.

We might further consider the latter as involving two overlapping groups: those

who experienced the public performative elements of ‘City Sites’ and the conference,

and those who encountered the book in the mid-1990s soon after it was published.

We might look at the media audience — press coverage of the individual parts and

early reviews — and also the book’s longer arc of resonance (or dissonance) within

current conversations. Such analytic tools can be useful prompts in assessing current

work, and might aid in dissecting varied facets of activist and aesthetic projects

with precision.

11 Young artists can now receive formal training in arenas that would have been labeled ‘new genre’

twenty years ago — for instance an MFA in Public Practice from OTIS College of Art and Design in

Los Angeles — a programme chaired by Lacy — or an MFA in Art and Social Practice from Portland

State University.

12 See S. Lacy, ‘Debated Territory: Toward a Critical Language for Public Art’, in S. Lacy (ed.),

Mapping the Terrain, pp.171—85.

13 See Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents’, Artforum, vol.44, no.6,

February 2006, pp.178—83; and Grant Kester’s response letter and Bishop’s response to his response

(Artforum, vol.44, no.9, May 2006, p.22).

72 | Afterall

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lacy’s polemical call for a new criticism is even more to the point. To quote at length:

The introduction of multiple contexts for visual art presents a legitimate dilemma

for critics: what forms of evaluation are appropriate when the sites of reception

for the work, and the premise of ‘audience’, have virtually exploded? […] In the

instances throughout this century when art has moved outside the confines of

traditional exhibition venues, or even remained within them and challenged the

nature and social meaning of art, analysis has been a contested and politicised

terrain. Until a critical approach is realised, this work will remain relegated to

outsider status in the art world, and its ability to transform our understanding

of art and artists’ roles will be safely neutralised. Misconceptions and confused

thinking abound. What is needed at this point is a more subtle and challenging

criticism in which assumptions — both those of the critic and those of the artists

— are examined and grounded within the worlds of both art and social discourse.

Suzanne Lacy, Notions of interaction, audience, artists’ intentions and effectiveness are too freely

Three Weeks in May, used, often without sufficient interrogation and almost never within comprehensive

1977, guerilla

performance, conceptual schemes that differentiate and shed meaning on the practice of new

Los Angeles. genre public art. 14

Photograph:

the artist. Courtesy

the artist In relation to current practices it might do us good to look back even further, to the work

of artists like Allan Kaprow, Lacy’s teacher and someone she encouraged to participate

in ‘City Sites’ and Mapping the Terrain because she saw connections between his work

and those of younger colleagues. Consideration of shared elements and disjunctures seem

useful for all of us as we keep assessing and exploring — not with any hagiographic intent

but rather so that we might strengthen current practice and theory. Although it might

mark me as overly romantic — far more so than Lacy — it seems fitting to close by returning

to that moment twenty years ago, when Mierle Laderman Ukeles stood amidst that

gathering and began her three-minute speech by saying, ‘Thank you, Suzanne. I like being

in your artwork right now. It’s a beautiful thing for all of us.’

14 S. Lacy (ed.), Mapping the Terrain, op. cit., pp.172—73.

Contexts: Mapping the Terrain | 73

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.8 on Sat, 24 Jul 2021 19:04:21 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Artist's Guide to Public Art: How to Find and Win Commissions (Second Edition)From EverandThe Artist's Guide to Public Art: How to Find and Win Commissions (Second Edition)No ratings yet

- Conversation and Community in Modern ArtDocument4 pagesConversation and Community in Modern ArtAlumno Xochimilco GUADALUPE CECILIA MERCADO VALADEZNo ratings yet

- The Rise of the Curator in International Contemporary ArtDocument13 pagesThe Rise of the Curator in International Contemporary ArtRevista Feminæ LiteraturaNo ratings yet

- Art as Social Action: An Introduction to the Principles and Practices of Teaching Social Practice ArtFrom EverandArt as Social Action: An Introduction to the Principles and Practices of Teaching Social Practice ArtNo ratings yet

- Terante Stern Lesson 11Document4 pagesTerante Stern Lesson 11Richelle MasingNo ratings yet

- Locus Book Draft 7Document278 pagesLocus Book Draft 7Anton Cu UnjiengNo ratings yet

- The Dematerialization of Architecture:: Toward A Taxonomy of Conceptual PracticeDocument23 pagesThe Dematerialization of Architecture:: Toward A Taxonomy of Conceptual PracticeFelipeNo ratings yet

- Art, Politics and New Media: Randall PackerDocument5 pagesArt, Politics and New Media: Randall Packerrikrik1212No ratings yet

- Mapping The TerrainDocument7 pagesMapping The TerrainJody TurnerNo ratings yet

- After AllDocument139 pagesAfter Allemprex100% (3)

- Taking place: Building histories of queer and feminist art in North AmericaFrom EverandTaking place: Building histories of queer and feminist art in North AmericaNo ratings yet

- Public Sculpture Examining The Differences Between Contemporary Sculpture Inside and Outside The Art InstitutionDocument20 pagesPublic Sculpture Examining The Differences Between Contemporary Sculpture Inside and Outside The Art InstitutionYasmin WattsNo ratings yet

- Modern and Contemporary ArtDocument5 pagesModern and Contemporary ArtMARLA JOY LUCERNANo ratings yet

- Enson MichaelDocument13 pagesEnson MichaelFelipe Suárez MiraNo ratings yet

- Buchloh, Conceptual ArtDocument40 pagesBuchloh, Conceptual ArtedrussoNo ratings yet

- Brenson Michael The Curator's MomentDocument13 pagesBrenson Michael The Curator's MomentMira AndraNo ratings yet

- Week 13 Contemporary ArtDocument4 pagesWeek 13 Contemporary ArtJade CarbonNo ratings yet

- Becker Art Collective Action 1974Document11 pagesBecker Art Collective Action 1974sara_zoblNo ratings yet

- The Artist's Guide to Public Art: How to Find and Win CommissionsFrom EverandThe Artist's Guide to Public Art: How to Find and Win CommissionsNo ratings yet

- Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipFrom EverandArtificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of SpectatorshipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- A People's Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice MovementsFrom EverandA People's Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice MovementsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Participatory Art Finkelpearl Encyclopedia AestheticsDocument8 pagesParticipatory Art Finkelpearl Encyclopedia AestheticsDiana Delgado-UreñaNo ratings yet

- Nervous SystemsDocument38 pagesNervous Systemsmlaure445No ratings yet

- Becker Art As Collective ActionDocument11 pagesBecker Art As Collective Actionmigkay100% (1)

- Curatorial Conversations: Cultural Representation and the Smithsonian Folklife FestivalFrom EverandCuratorial Conversations: Cultural Representation and the Smithsonian Folklife FestivalNo ratings yet

- Grupo de Arte Callejero: Thought, Practice, and ActionsFrom EverandGrupo de Arte Callejero: Thought, Practice, and ActionsNo ratings yet

- Art As Collective Action PDFDocument11 pagesArt As Collective Action PDFVictoria de Freitas LeiteNo ratings yet

- J ctv16zk03m 33Document13 pagesJ ctv16zk03m 33Floribert Hoken'sNo ratings yet

- Assesing Socially Engaged ArtDocument12 pagesAssesing Socially Engaged ArtSanne DolkNo ratings yet

- Art Appreciation ReviewerDocument14 pagesArt Appreciation ReviewerNoriel TorreNo ratings yet

- Critical Terms for Art History, Second EditionFrom EverandCritical Terms for Art History, Second EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Anthropology As Art, Art As AnthropologyDocument1 pageAnthropology As Art, Art As AnthropologyCarlos Eduardo SilvaNo ratings yet

- Transform A ChangDocument16 pagesTransform A ChangTania MarilinNo ratings yet

- Social Art A Community ApproachDocument14 pagesSocial Art A Community ApproachDoğan AkbulutNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Collective Action - Ellen Mara de WachterDocument12 pagesA Brief History of Collective Action - Ellen Mara de Wachterana gomesNo ratings yet

- Feminist Time: A Conversation: Grey Room April 2008Document37 pagesFeminist Time: A Conversation: Grey Room April 2008Lenz21No ratings yet

- ENVIRONMENTAL and ARCHITECTURAL PHENOMENDocument49 pagesENVIRONMENTAL and ARCHITECTURAL PHENOMENsoporte.mt.ihNo ratings yet

- phillips-2021-the-issue-is-moot-decolonizing-art-artifactDocument23 pagesphillips-2021-the-issue-is-moot-decolonizing-art-artifactMelina SantosNo ratings yet

- A Collectography of PAD/D by Gregory SholetteDocument15 pagesA Collectography of PAD/D by Gregory SholetteAntonio SernaNo ratings yet

- 0 Simona Dvorak and Tadeo Kohan_Présentation - cda-2.pptxDocument19 pages0 Simona Dvorak and Tadeo Kohan_Présentation - cda-2.pptxSusana AriasNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Contexts that Shape Artistic Production and ReceptionDocument8 pagesUnderstanding the Contexts that Shape Artistic Production and ReceptionCristina Maquinto50% (2)

- Mattern ClickScanBoldDocument25 pagesMattern ClickScanBoldThanga Baskar ShanmugamNo ratings yet

- Roux - Participative ArtDocument4 pagesRoux - Participative ArtTuropicuNo ratings yet

- The Modern Moves West: California Artists and Democratic Culture in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandThe Modern Moves West: California Artists and Democratic Culture in the Twentieth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Tasa BookletDocument27 pagesTasa Bookleterikammm17No ratings yet

- Birth of A MovementDocument27 pagesBirth of A MovementUCLA_SPARCNo ratings yet

- ENV M1Cw – Ecoventions in ArtDocument4 pagesENV M1Cw – Ecoventions in ArtMosor VladNo ratings yet

- Denise Scott BrownDocument7 pagesDenise Scott BrownSelcen YeniçeriNo ratings yet

- Cole, Ross (2014) - "'Sound Effects (O.K., Music) ' Steve Reich and The Visual Arts in New York City, 1966-1968".Document28 pagesCole, Ross (2014) - "'Sound Effects (O.K., Music) ' Steve Reich and The Visual Arts in New York City, 1966-1968".Maxim FielderNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics in Its American IdeologyDocument10 pagesAesthetics in Its American IdeologyAnne-MarieNo ratings yet

- Fraser Introduction 2018Document7 pagesFraser Introduction 2018madhu smritiNo ratings yet

- Lesson: Caught in Between: Modern and Contemporary ArtDocument14 pagesLesson: Caught in Between: Modern and Contemporary Artjessica navajaNo ratings yet

- Area - 2005 - Gibson - Subversive Sites Rave Culture Spatial Politics and The Internet in Sydney AustraliaDocument15 pagesArea - 2005 - Gibson - Subversive Sites Rave Culture Spatial Politics and The Internet in Sydney AustraliabenreidoxxNo ratings yet

- Making the Scene in the Garden State: Popular Music in New Jersey from Edison to Springsteen and BeyondFrom EverandMaking the Scene in the Garden State: Popular Music in New Jersey from Edison to Springsteen and BeyondNo ratings yet

- TASADocument22 pagesTASAbrittanyclapperNo ratings yet

- 2006 AstaKuusinen ShootingfromtheWildZone PhdThesis LauraAguilarDocument354 pages2006 AstaKuusinen ShootingfromtheWildZone PhdThesis LauraAguilarluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 2007 Kac Space PoetryDocument2 pages2007 Kac Space Poetryluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Antagonists Guide To The Assholes of L ADocument13 pagesAntagonists Guide To The Assholes of L Aluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 1973 Hartman&Kessler UrbanRenewal YerbaBuena LandEconomics Nov1 1973Document15 pages1973 Hartman&Kessler UrbanRenewal YerbaBuena LandEconomics Nov1 1973luis_rhNo ratings yet

- 2017 DiazInfante UlisesIDocument53 pages2017 DiazInfante UlisesIluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 1967 UNODA Treaty PrinciplesGoverningActivitiesofStatesDocument5 pages1967 UNODA Treaty PrinciplesGoverningActivitiesofStatesluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 2016 - ESA What Is Space4 (Dot) ZeroDocument2 pages2016 - ESA What Is Space4 (Dot) Zeroluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Key Words: Terrorism, Urban Geopolitics, Urbicide, WarDocument4 pagesKey Words: Terrorism, Urban Geopolitics, Urbicide, Warluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Conflict Over Border Art': Third TextDocument16 pagesConflict Over Border Art': Third Textluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Langfeld Canon in Art History PDFDocument18 pagesLangfeld Canon in Art History PDFMarc JacquinetNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Chicano Art PDFDocument41 pagesContemporary Chicano Art PDFPaola ArboledaNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary Art Market Report 2020Document76 pagesThe Contemporary Art Market Report 2020luis_rhNo ratings yet

- Beneath The Paving Stones Situationists and The Beach May 1968Document122 pagesBeneath The Paving Stones Situationists and The Beach May 1968luis_rhNo ratings yet

- Your Country Needs You: A Case Study in Political IconographyDocument24 pagesYour Country Needs You: A Case Study in Political Iconographyluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Moma CatalogueDocument259 pagesMoma CatalogueYangodelosreindhartNo ratings yet

- Talk to Kids About Healthy RelationshipsDocument8 pagesTalk to Kids About Healthy Relationshipsluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 1987 - Feminist Critique of Art HistoryDocument33 pages1987 - Feminist Critique of Art Historyluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 01 Black Skins White MasksDocument26 pages01 Black Skins White Masksluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Raphaelmontanez WhitneyDocument12 pagesRaphaelmontanez Whitneyluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Foster The Politics of Signifier 1993Document26 pagesFoster The Politics of Signifier 1993sNo ratings yet

- 1994 Moxey Bosch WorldUpsideDownDocument38 pages1994 Moxey Bosch WorldUpsideDownluis_rhNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.41 On Fri, 19 Feb 2021 05:19:30 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 132.248.9.41 On Fri, 19 Feb 2021 05:19:30 UTCluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Heiter Skelter: L.A. Art in The 9o'sDocument2 pagesHeiter Skelter: L.A. Art in The 9o'sluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 1992 05 HelterSkelter reviewonPrintCollectorsDocument3 pages1992 05 HelterSkelter reviewonPrintCollectorsluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 2012 Punkademics WebDocument235 pages2012 Punkademics Webluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 2008 Phantom SightiDocument248 pages2008 Phantom Sightiluis_rhNo ratings yet

- 2008 - Pettibon - As A Young Punk - ArtinAmericaDocument6 pages2008 - Pettibon - As A Young Punk - ArtinAmericaluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Curatin GattheedgeDocument131 pagesCuratin Gattheedgeluis_rhNo ratings yet

- Surf Culture: The Art History of SurfingDocument123 pagesSurf Culture: The Art History of Surfingluis_rh100% (1)

- UcspDocument4 pagesUcspEla AmarilaNo ratings yet

- AFS 100 Lecture 1 Introduction To African StudiesDocument28 pagesAFS 100 Lecture 1 Introduction To African StudiesJohn PhilbertNo ratings yet

- What You'Ve Been Missing (Pilot) Season 01 Episode 01 (10.22.10)Document26 pagesWhat You'Ve Been Missing (Pilot) Season 01 Episode 01 (10.22.10)8thestate50% (2)

- Eo BCPCDocument3 pagesEo BCPCRohaina SapalNo ratings yet

- Guerrero v. Director Land Management BureauDocument12 pagesGuerrero v. Director Land Management BureauJam NagamoraNo ratings yet

- Jacob Frydman vs. Nasi Seed Investors, Et AlDocument8 pagesJacob Frydman vs. Nasi Seed Investors, Et AlJayNo ratings yet

- TP304 03Document50 pagesTP304 03baranfilmNo ratings yet

- Hassan Management Services Opens For Business and Completes ThesDocument1 pageHassan Management Services Opens For Business and Completes ThesM Bilal SaleemNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument3 pagesThesisCarmela CanillasNo ratings yet

- Effects of Result-Based Capability Building Program On The Research Competency, Quality and Productivity of Public High School TeachersDocument11 pagesEffects of Result-Based Capability Building Program On The Research Competency, Quality and Productivity of Public High School TeachersGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument18 pagesChapter IHarold Marzan FonacierNo ratings yet

- Noli Me TangereDocument2 pagesNoli Me TangereLilimar Hao EstacioNo ratings yet

- Colors For Trombone PDF AppermontDocument2 pagesColors For Trombone PDF AppermontJames0% (7)

- Chapter 1 IntroductionDocument60 pagesChapter 1 IntroductionAndrew Charles HendricksNo ratings yet

- Name: - 2019 Political Documentary - War TV-14Document5 pagesName: - 2019 Political Documentary - War TV-14Yairetza VenturaNo ratings yet

- Karen Weixel-Dixon - Existential Group Counselling and Psychotherapy-Routledge (2020)Document186 pagesKaren Weixel-Dixon - Existential Group Counselling and Psychotherapy-Routledge (2020)Marcel NitanNo ratings yet

- High Performance School Ancash Offers World of OpportunitiesDocument2 pagesHigh Performance School Ancash Offers World of OpportunitieswilliamNo ratings yet

- John Warren 1555Document2 pagesJohn Warren 1555Bently JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Securitization of IPDocument8 pagesSecuritization of IPKirthi Srinivas GNo ratings yet

- Correspondence Between BVAG and CLLR Mark WilliamsDocument12 pagesCorrespondence Between BVAG and CLLR Mark WilliamsBermondseyVillageAGNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Procurement and Contract AdministrationDocument5 pagesAssignment On Procurement and Contract Administrationasterayemetsihet87No ratings yet

- Zsuzsanna Budapest - The Holy Book of Women's Mysteries (PP 104-305)Document109 pagesZsuzsanna Budapest - The Holy Book of Women's Mysteries (PP 104-305)readingsbyautumn100% (1)

- Essay USP B. Inggris 21-22 PDFDocument3 pagesEssay USP B. Inggris 21-22 PDFMelindaNo ratings yet

- Requirements For Marriage Licenses in El Paso County, Texas: Section 2.005. See Subsections (B 1-19)Document2 pagesRequirements For Marriage Licenses in El Paso County, Texas: Section 2.005. See Subsections (B 1-19)Edgar vallesNo ratings yet

- ECHR Rules on Time-Barred Paternity Claim in Phinikaridou v CyprusDocument24 pagesECHR Rules on Time-Barred Paternity Claim in Phinikaridou v CyprusGerasimos ManentisNo ratings yet

- Public auction property saleDocument1 pagePublic auction property salechek86351No ratings yet

- Successful Telco Revenue Assurance: Rob MattisonDocument4 pagesSuccessful Telco Revenue Assurance: Rob Mattisonashish_dewan_bit909No ratings yet

- Writing Assignment: Student Name: Randa Aqeel Al Rashidi ID: 411004123Document6 pagesWriting Assignment: Student Name: Randa Aqeel Al Rashidi ID: 411004123Atheer AlanzyNo ratings yet

- The Essential Drucker Book Review 131012023243 Phpapp02Document39 pagesThe Essential Drucker Book Review 131012023243 Phpapp02germinareNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of the Philippines upholds constitutionality of Act No. 2886Document338 pagesSupreme Court of the Philippines upholds constitutionality of Act No. 2886OlenFuerteNo ratings yet