Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 190.164.218.83 On Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

Uploaded by

valentina antonia silva galvezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 190.164.218.83 On Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

Uploaded by

valentina antonia silva galvezCopyright:

Available Formats

Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety

Author(s): Elaine K. Horwitz, Michael B. Horwitz and Joann Cope

Source: The Modern Language Journal , Summer, 1986, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Summer, 1986),

pp. 125-132

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the National Federation of Modern Language Teachers

Associations

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/327317

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/327317?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations and Wiley are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Modern Language Journal

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety

ELAINE K. HORWITZ, MICHAEL B. HORWITZ, AND JOANN COPE

"IJUST KNOW I HAVE SOME KIND OF DISABILITY: I CAN'Tstudents generally feel strongly that anxiety is

learn a foreign language no matter how hard I try." a major obstacle to be overcome in learning to

"When I'm in my Spanish class I just freeze! I can't think speak another language, and several recent ap-

of a thing when my teacher calls on me. My mind goes blank.proaches

" to foreign language teaching, such as

"Ifeel like my French teacher is some kind of Martian death

community language learning and suggesto-

ray. I never know when he'll point at me!" pedia, are explicitly directed at reducing learner

"It's about time someone studied why some people can't learn

anxiety. However, second language research

languages. "I

has neither adequately defined foreign language

Such statements are all too familiar to anxiety nor described its specific effects on for-

teachers of foreign languages. Many eign people

language learning. This paper attempts to

fill this gap by identifying foreign language

claim to have a mental block against learning

a foreign language, although these same anxiety

peopleas a conceptually distinct variable in

may be good learners in other situations, foreign language learning and interpreting it

strongly motivated, and have a sincere within

likingthe context of existing theoretical and

for speakers of the target language. What,empirical

then, work on specific anxiety reactions.

prevents them from achieving their The symptoms and consequences of foreign

desired

goal? In many cases, they may have an language

anxiety anxiety should thus become readily

identifiable to those concerned with language

reaction which impedes their ability to perform

learning and teaching.

successfully in a foreign language class. Anxiety

is the subjective feeling of tension, apprehen-

sion, nervousness, and worry associated with

EFFECTS OF ANXIETY ON LANGUAGE LEARNING

an arousal of the autonomic nervous system.2 Second Language Studies. For many

Just as anxiety prevents some people from per-

scholars have considered the anxiety-pr

forming successfully in science or mathematics,

potential of learning a foreign lang

many people find foreign language learning,

Curran and Stevick discuss in detail the defen-

especially in classroom situations, particularly

sive position imposed on the learner by most

stressful.

language teaching methods; Guiora argues that

When anxiety is limited to the language

language learning itself is "a profoundly un-

learning situation, it falls into the category ofpsychological proposition" because it

settling

specific anxiety reactions. Psychologists directly

use thethreatens an individual's self-concept

term specific anxiety reaction to differentiate

and worldview.4 More recently researchers

people who are generally anxious in a variety

have attempted to quantify the effects of anxiety

of situations from those who are anxious only

on foreign language learning, but these efforts

in specific situations. Researchers have identi-

have met with mixed results. While the perti-

fied several specific anxieties associated

nentwith

studies have differed in the measures em-

school tasks such as test-taking and with aca-

ployed, they can generally be characterized by

demic subjects such as mathematics or science.3

their comparison of students' self-reports of

Second language researchers and theorists

anxiety with their language proficiency ratings,

have long been aware that anxiety is often asso- through a discrete skills task or a

obtained

ciated with language learning. Teachers and

global measure such as final course grade. In

his 1978 review of research, Scovel argues that

scholars have been unable to establish a clear-

The Modern Language Journal, 70, ii (1986) cut relationship between anxiety and overall

0026-7902/86/0002/125 $1.50/0

?1986 The Modern Language Journal

foreign language achievement; he attributes the

discrepant findings at least in part to the in-

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

126 Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope

consistency of anxiety measures

Clinical Experience. used

The subjective feelings,

cludes: "It is psycho-physiological

perhaps symptoms, and be-

premature to

havioral responsesand

[anxiety] to the global of the anxious foreign lan-

comprehe

guage learner are essentially the same as for any

of language acquisition.'"5

specific anxiety.

Studies seeking more They experience apprehen-

specific effects

iety on language sion,

learning

worry, even dread. They

have have difficulty

been

concentrating,

vealing. Kleinmann foundbecome forgetful,

that sweat, and

ESL

with high levelshaveof debilitating

palpitations. They exhibit avoidance be- an

havior types

tempted different such as missingofclass and postponing

gramma

structions than did

homework.less

Clinical anxious ESL

experience with foreign

and Steinberg andlanguage students in university

Horwitz foundclasses and atthat

experiencing an the Learning Skills Center (LSC) at the Uni-

anxiety-producing

attempted less interpretive

versity of Texas also suggests several(more

discrete

problems causedexperiencing

messages than those by anxiety and illustrates

condition.6 These poignantly

studies how these problems

indicatecan interfere tha

with language learning. Principally, counselors

can affect the communication strate

dents employ in find language

that anxiety centers on the class.

two basic task Th

more anxious student

requirements oftends to

foreign language avoid

learning: lis-

tening and speaking. Difficulty

ing difficult or personal messages in speaking in in

language. These class

findings are cited

is probably the most frequently alsocon- c

with research oncern of the anxioustypes

other foreign language students

of spec

seeking help

munication anxiety. at the LSC. Students often report

Reseachers study

that they feel fairly comfortable

ing in a native language have respondingfound to t

dents with highera drill or delivering

levels of prepared speeches in theiranx

writing

foreign language

shorter compositions and class but tend to "freeze" in

qualify thei

a role-play situation.

less than their calmer A female student speaks

counterparts d

A review of the of

literature found

the evenings in her dorm room only

spent rehears-

ing what she designed

strument specifically should have said in classto

the daymea

eign language before. Anxious language

anxiety. learners also com-

Gardner, C

plain of difficulties

Smythe, and Smythe discriminating the sounds

developed five

and structures

measure French class of a target language

anxiety as message.

part

test battery onOne male student claims to hear

attitudes and only a loud

mot

Gardner, Smythe, Clement,

buzz whenever and G

his teacher speaks the foreign

language. Anxious

found small negative students may also have dif-

correlations (ran

ficulty grasping

r = -.13 to r = -.43) between the content of athis

target language

scale

measures of message. Many LSC clients (aural

achievement claim that they com

sion, speaking, have little orgrade,

final no idea of what the

andteacher isa

say-com

three sub-scales of the Canadian Achievement ing in extended target language utterances.

Test in French).9 Foreign language anxiety frequently shows

up in testing situations. Students commonly re-

This brief review suggests two reasons for the

dearth of conclusions concerning anxiety and port to counselors that they "know" a certain

second language achievement. First, the anx-grammar point but "forget" it during a test or

iety measures typically have not been specific an oral exercise when many grammar points

must be remembered and coordinated simul-

to foreign language learning. Only the research

by Gardner utilized a measure relevant to lan-taneously. The problem can also be isolated in

guage anxiety, and it was restricted to French persistent "careless" errors in spelling or syn-

tax. The student realizes, usually some time

classroom anxiety. Second, few achievement

studies have looked at the subtle effects of anx- after the test, that s/he knew the correct answer

iety on foreign language learning. Although re- but put down the wrong one due to nervous-

search has not clearly demonstrated the effect ness. If the student realizes s/he is making pre-

of anxiety on language learning, practitioners ventable errors during the test, anxiety - and

have had ample experience with anxious errors - may escalate.

learners. Overstudying is a related phenomenon. Stu-

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety 127

FOREIGN LANGUAGE ANXIETY: CONCEPTUAL

dents who are overly concerned about their per-

FOUNDATIONS

formance may become so anxious when they

Because to

make errors, they may attempt foreign language anxiety con

compensate

by studying even more. performance evaluation within

Their frustration is an aca

understandable when theirand social context, effort

compulsive it is useful to draw pa

does not lead to improvedbetween

grades. it and

Onethree related performance

bright

woman who had lived inties: 1) communication

Mexico spent eightapprehension;

hours a day preparing for anxiety; and 3) fear

a beginning of negative evaluatio

Spanish

class --and still did poorly. to its emphasis

The reverseon interpersonal

be- interact

havior is also possible. Anxious the construct of communication

students may apprehe

avoid studying and in some is quite cases

relevantskip

to the class

conceptualization o

entirely in an effort to alleviate eign language

their anxiety. 3 Communicati

anxiety.

Certain beliefs about language prehension is a type also

learning of shyness characte

contribute to the student's tension and frustra- by fear of or anxiety about communicatin

tion in the classroom. We note that a number people. Difficulty in speaking in dya

of students believe nothing should be saidgroups

in (oral communication anxiety) or i

the foreign language until it can be said cor-

lic ("stage fright"), or in listening to or le

rectly and that it is not okay to guess an un-

a spoken message (receiver anxiety) are all

known foreign language word.10 Beliefs such festations of communication apprehen

as these must produce anxiety since students Communication apprehension or some si

are expected to communicate in the second reaction obviously plays a large role in f

language anxiety. People who typically

tongue before fluency is attained and even ex-

cellent language students make mistakes or for- trouble speaking in groups are likely to e

get words and need to guess more than occa- ence even greater difficulty speaking in

sionally. eign language class where they have litt

In light of current theory and research in sec- trol of the communicative situation and their

ond language acquisition, the problem of anx- performance is constantly monitored. More-

iety and the accompanying erroneous beliefs over, in addition to all the usual concerns about

about language learning discussed here repre- oral communication, the foreign language class

sent serious impediments to the development requires the student to communicate via a

of second language fluency as well as to per- medium in which only limited facility is pos-

formance. Savignon stresses the vital role of sessed. The special communication apprehen-

spontaneous conversational interactions in the sion permeating foreign language learning de-

development of communicative competence, rives from the personal knowledge that one will

while Krashen argues that the extraction of almost certainly have difficulty understanding

meaning from second language messages (sec- others and making oneself understood. Possibly

ond language acquisition in his terminology) because of this knowledge, many otherwise

is the primary process in the development of talkative people are silent in a foreign language

a second language."1 Anxiety contributes to an class. And yet, the converse also seems to be

affective filter, according to Krashen, which true. Ordinarily self-conscious and inhibited

makes the individual unreceptive to language speakers may find that communicating in a for-

input; thus, the learner fails to "take in" the eign language makes them feel as if someone

available target language messages and lan- else is speaking and they therefore feel less

guage acquisition does not progress.12 The anxious. 14This phenomenon may be similar

anxious student is also inhibited when attempt- to stutterers who are sometimes able to enun-

ing to utilize any second language fluency he ciate normally when singing or acting.

or she has managed to acquire. The resulting Since performance evaluation is an ongoing

poor test performance and inability to perform feature of most foreign language classes, test-

in class can contribute to a teacher's inaccurate anxiety is also relevant to a discussion of for-

assessment that the student lacks either some eign language anxiety. Test-anxiety refers to a

necessary aptitude for learning a language or type of performance anxiety stemming from a

sufficient motivation to do the necessary work fear of failure.15 Test-anxious students often put

for a good performance. unrealistic demands on themselves and feel that

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

128 Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope

anything less than in the L2

ais perfect

likely to challenge an test

individual's per

is a failure. Students who are test-anxious in self-concept as a competent communicator and

foreign language class probably experience con-lead to reticence, self-consciousness, fear, or

even panic.

siderable difficulty since tests and quizzes are

frequent and even the brightest and most pre-Authentic communication also becomes

pared students often make errors. Oral tests problematic in the second language because of

have the potential of provoking both test- and the immature command of the second language

oral communication anxiety simultaneously relative

in to the first. Thus, adult language

susceptible students. learners' self-perceptions of genuineness in pre-

Fear of negative evaluation, defined as "ap-senting themselves to others may be threatened

prehension about others' evaluations, avoid- by the limited range of meaning and affect tha

ance of evaluative situations, and the expecta- can be deliberately communicated. In sum, the

tion that others would evaluate oneself nega- language learner's self-esteem is vulnerable to

the awareness that the range of communicative

tively," is a third anxiety related to foreign lan-

guage learning.16 Although similar to test anx-choices and authenticity is restricted. The

iety, fear of negative evaluation is broader importance

in of the disparity between the "true

scope because it is not limited to test-taking self as known to the language learner and the

situations; rather, it may occur in any social,more limited self as can be presented at any

evaluative situation such as interviewing for given

a moment in the foreign language would

job or speaking in foreign language class. seem to distinguish foreign language anxiety

Unique among academic subject matters, for- from other academic anxieties such as those

eign languages require continual evaluation associated

by with mathematics or science. Prob-

ably no other field of study implicates self-

the only fluent speaker in the class, the teacher.

Students may also be acutely sensitive to the concept and self-expression to the degree that

language study does.

evaluations - real or imagined - of their peers.

Although communication apprehension, test

anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation pro- IDENTIFYING FOREIGN LANGUAGE ANXIETY

vide useful conceptual building blocks for a de-

scription of foreign language anxiety, we pro- Since anxiety can have profound effect

many aspects of foreign language learnin

pose that foreign language anxiety is not simply

the combination of these fears transferred to is important to be able to identify those stu

foreign language learning. Rather, we conceive who are particularly anxious in foreign

foreign language anxiety as a distinct complex guage class. During the summer of 1983,

of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and be- dents in beginning language classes at the

haviors related to classroom language learning versity of Texas were invited to participa

arising from the uniqueness of the language a "Support Group for Foreign Language L

learning process. ing." Of the 225 students informed of the

Adults typically perceive themselves as rea- port groups, seventy-eight, over one-t

sonably intelligent, socially-adept individuals, were concerned enough about their foreign

sensitive to different socio-cultural mores. guage class to indicate that they would li

These assumptions are rarely challenged when join such a group. Due to time and space l

communicating in a native language as it is tations, participation had to be limited to

usually not difficult to understand others or to groups of fifteen students each. Group m

make oneself understood. However, the situa-ings consisted of student discussion of con

tion when learning a foreign language standsand difficulties in language learning, did

in marked contrast. Because individual com- presentations on effective language lear

munication attempts will be evaluated accord- strategies, and anxiety management exer

ing to uncertain or even unknown linguistic The difficulties these students related were

and socio-cultural standards, second language compelling. They spoke of "freezing" in class,

communication entails risk taking and is neces-standing outside the door trying to summon up

sarily problematic. Because complex and non- enough courage to enter, and going blank prior

spontaneous mental operations are required into tests. They also reported many of the psycho-

order to communicate at all, any performancephysiological symptoms commonly associated

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety 129

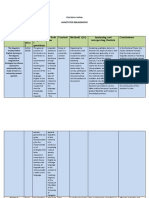

TABLE I

with anxiety (tenseness, trembling, perspiring,

FLCAS Items with Percentages of Students Selecting

palpitations, and sleep disturbances).

Each Alternative

The experiences related in the support

groups contributed to the development

SA* A N D SD of the

Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale

1. I never feel quite sure of

(FLCAS).'7 The scale has demonstrated in my foreign language cla

internal reliability, achieving an alpha coeffi- 11** 51 17 20 1

cient of .93 with all items producing significant 2. I don't worry about making

corrected item-total scale correlations. Test- 11 23 1 53 12

retest reliability over eight weeks yielded 3.

an I

when I know t tremble

in language class.

r = .83 (p <.001). A construct validation study 5 16 31 29 19

is currently underway to establish foreign lan-

4. It frightens me when I

guage anxiety as a phenomenon related to but teacher is saying in the f

distinguishable from other specific anxieties. 18 8 27 29 20 16

Pilot testing with the FLCAS affords an

5. It wouldn't bother me at

guage classes.

opportunity to examine the scope and severity

15 47 12 16 11

of foreign language anxiety. To date, the re-

sults demonstrate that students with debilitat- 6. During language class, I fi

things that have nothing to

ing anxiety in the foreign language classroom 7 19 31 32 12

setting can be identified and that they share 7.

a I keep thinking that the

number of characteristics in common. The re- languages than I am.

sponses of seventy-five university students 13 25 20 28 13

(thirty-nine males and thirty-six females rang-8. I am usually at ease during

5 35 19 20 21

ing in age from eighteen to twenty-seven) from

9. I start to panic when I ha

four intact introductory Spanish classes are re-

tion in language class.

ported here. The FLCAS was administered to 12 37 19 28 4

the students during their scheduled language 10. I worry about the conse

class the third week of the semester. language class.

The items presented are reflective of com- 25 17 12 29 16

11.

munication apprehension, test-anxiety, and I don't understand why so

foreign language classes.

fear of negative evaluation in the foreign lan-

5 17 36 37 4

guage classroom. Responses to all FLCAS

12. In language class, I can

items are reported in Table I. All percentages I know.

refer to the number of students who agreed or 9 48 11 25 7

strongly agreed (or disagreed and strongly dis- 13. It embarrasses me to vo

class.

agreed) with statements indicative of foreign

0 9 19 57 15

language anxiety. (Percentages are rounded to

14. I would not be nervou

the nearest whole number.)

with native speakers.

Students who test high on anxiety report that 5 12 17 51 15

they are afraid to speak in the foreign language. 15. I get upset when I don

They endorse FLCAS items indicative of is correcting.

speech anxiety such as "I start to panic when 1 31 28 37 3

I have to speak without preparation in language 16. Even if I am well pre

anxious about it.

class" (49 %); "I get nervous and confused when

5 37 17 24 16

I am speaking in my language class" (33 %); "I

17. I often feel like not goi

feel very self-conscious about speaking the for- 19 28 19 23 12

eign language in front of other students" (28%). 18. I feel confident when I spe

They also reject statements like "I feel confident 1 28 24 43 4

when I speak in foreign language class" (47%). 19. I am afraid that my lan

Anxious students feel a deep self-consciousness every mistake I make.

0 15 31 40 15

when asked to risk revealing themselves by

20. I can feel my heart p

speaking the foreign language in the presence called on in language cla

of other people. 5 27 19 37 12

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

130 Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope

TABLE I prehending the target language message they

(continued)

must understand every word that is spoken.

SA* A N D SD

Anxious students also fear being less com-

petent

21. The more I study for than other students

a language or being

test, negatively

the more c

fused I get. evaluated by them. They report: "I keep think-

4 12 8 48 28

ing that other students are better at languages

22. I don't feel pressure to prepare very well for

class.

than I am" (38%); "I always feel that the other

3 12 19 44 23 students speak the foreign language better than

23. I always feel"language

that

students theI do"

class moves

speak (31%);

so quickly,

other

the for

language better than II worry

about getting left behind" (59%); "it

do.

12 19 25 31 13 embarrasses me to volunteer answers in my

languageabout

24. I feel very self-conscious class" (9%); "I am afraid that

speaking the thefore

language in front of other students.

other students will laugh at me when I speak

3 25 19 47 7

the foreign language" (10%). Thus, they may

25. Language class moves so quickly I worry abou

left behind. skip class, overstudy, or seek refuge in the last

16 43 11 28 3

row in an effort to avoid the humiliation or em-

26. I feel more tense andbarrassment

nervous of being

in called

myonlanguage

to speak. clas

in my other classes. Anxious students are afraid to make mistakes

13 25 19 31 12

in the foreign language. They endorse the state-

27. I get nervous and confused

ment "I am when

afraid thatImy

am speaking

language teacher is in m

language class.

5 28 28 31 8

ready to correct every mistake I make" (15%),

while disagreeing with "I don't worry about mak-

28. When I'm on my way to language class, I feel v

and relaxed. ing mistakes in language class" (65 %). These

5 27 40 24 4 students seem to feel constantly tested and to

29. I get nervous whenperceive

I don't every correction

understandas a failure. every w

language teacher says.

Student responses to two FLCAS items - "I

3 24 24 43 7

feel overwhelmed by the number of rules you

30. I feel overwhelmed by the number of rules yo

have to learn to speak a foreign language"

to learn to speak a foreign language.

9 25 32 32 1 (34%) and "I feel more tense and nervous in

31. I am afraid that myother

the language class than in my other

students willclasses"

laugh

when I speak the (38%)--lend

foreign further support to the view that

language.

3 7 20 53 17 foreign language anxiety is a distinct set of be-

32. I would probably feel comfortable

liefs, perceptions, around

and feelings in response to n

speakers of the

language. foreign

foreign language learning in the classroom and

5 23 20 41 11

not merely a composite of other anxieties. The

33. I get nervous when the language teacher asks questions

latter item was found to be the single best dis-

which I haven't prepared in advance.

5 44 17 31 3 criminator of anxiety on the FLCAS as meas-

*SA = strongly agree; A

ured by its correlation with the total score.

= agree; N = neither agree n

agree; D = disagree; SD These results suggest thatdisagree.

= strongly anxious students feel

**Data in this table are uniquely unableto

rounded to deal

thewith nearest

the task of lan-

whole

ber. Percentages may guage

notlearning.

add to 100 due to roun

Our findings suggest that significant foreign

language anxiety is experienced by many stu-

dents in response to at least some aspects of for-

The fact that anxious eign language learning. A majority

students of the state-

fear they

not understand all ments reflective of foreign

language input language anxiety

is also

sistent with communication (nineteen of thirty-three items) were supported

apprehension.

dents endorse statements by a third or more

likeof the "it

studentsfrighten

surveyed,

when I don't understand what the teacher is and seven statements were supported by over

saying in the foreign language" (35%); "I gethalf the students. Although at this point we can

nervous when I don't understand every word only speculate as to how many people experi-

the language teacher says" (27%). They be-ence severe reactions to foreign language learn-

lieve that in order to have any chance of com-ing, these results (considered in light of the

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety 131

techniques

number of students who expressed should

a need forbe based on in

a student language-support philosophy and on

group) imply thatreducing defensiv

anxious students are common in foreign

in students. lan-

The impact of these (or

guage classrooms (at least inrective practices

beginning on foreign languag

classes

on the university level). and ultimate foreign language ac

must, of course, be studied in the c

PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

How much current teaching pra

In general, educators have twotribute

optionstowhen

foreign language anxie

dealing with anxious students: much is can

1) they due help

to the intrinsic nature

learning

them learn to cope with the existing are important issues to be

anxiety-

before

provoking situation; or 2) they firmthe

can make conclusions regardi

learning context less stressful. interventions

But before can be reached.

either

option is viable, the teacher must first acknowl-

CONCLUSIONS

edge the existence of foreign language anxiety.

Teachers probably have seen in their Scholars are only beginning to un

students

many or all of the negative effects

the role of of anxiety

anxiety in foreign languag

ing; we

discussed in this article, extremely do not

anxious yet know how pervasiv

stu-

dents are highly motivated to language

avoid engaging anxiety is nor do we compre

in the classroom activities theyprecise

fear most,repercussions

they in the classroom

may appear simply unpreparedknow or indifferent.

that individual reactions can var

Therefore, teachers should always Someconsider

studentsthe may experience an anxi

tion of

possibility that anxiety is responsible for such

the intensity

stu- that they post

quiredattributing

dent behaviors discussed here before foreign language courses until

poor student performance solely possible to lack of

moment or change their majo

ability, inadequate background,foreign

or poor moti- study. Students who

language

vation. Specific techniques which enceteachers

moderate mayanxiety may simply pr

nate in

use to allay students' anxiety include doing homework, avoid spe

relaxation

exercises, advice on effective class, or crouch

language learn- in the last row. Other

ing strategies, behavioral contracting, andexperience anxiety or

seldom, if ever,

journal keeping. 19 But languagein teachers

a foreign language class.

have

neither sufficient time nor adequate expertise

The effects of anxiety can extend be

classroom.

to deal with severe anxiety reactions. Such Just

stu- as math anxiety se

dents, when identified, should critical

probablyjob be re- channeling some w

filter,

some members

ferred for specialized help to outside counselors of other minority gro

from employing

or learning specialists.20 Therapists high-paying, high-demand m

behavior modification techniques, such as sys-

engineering careers, foreign language

tematic desensitization, have successfully

too, may play a role in students' selec

treated a variety of specific anxieties

courses,related

majors,to and ultimately, career

learning, and these techniques should

eign prove

language anxiety may also be a f

equally useful in the case of foreign

studentlanguage

objections to foreign language

anxiety. ments.

Reducing stress by changing the context

In recent of

years there have been signs of a

foreign language learning is the more

vival impor-

of interest in foreign language study

tant and considerably more difficult task.

as an applied As in conjunction with bus

skill

study,takes

long as foreign language learning for example,

place and for its intrin

in a formal school setting where evaluation

humanistic value is

as an essential part of a tr

inextricably tied to performance, anxiety

tional liberal is

education. With an increa

likely to continue to flourish. number

Teachers

of might

schools establishing or re-estab

create student support systems and closely

ing foreign language requirements, teac

monitor the classroom climate will

to identify spe- an even greater perc

likely encounter

cific sources of student anxiety.

age ofAs students

students vulnerable to foreign lang

appear to be acutely sensitive to targetThe

anxiety. language

rise of foreign language requ

corrections, the selection of error

mentscorrection

is occurring in conjunction with an

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

132 Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope

tive on

creased emphasis teacher who will acknowledge students' sp

spontaneous

the foreign language class.

feelings of isolation Since

and helplessness and offer sp

the target language concrete suggestons forto

seems attaining

be foreign

the lan- m

ening aspect of foreign guage confidence. Butlanguage lear

if we are to improve for-

current emphasis eignonlanguage

theteachingdevelopmen

at all levels of educa-

municative competence tion, we must recognize,

poses cope with, and even-

particul

difficulties for the anxious student. tually overcome, debilitating foreign language

Foreign language anxiety can probably be anxiety as a factor shaping students' experiences

alleviated, at least to an extent, by a suppor- in foreign language learning.

in Foreign Language Teaching (Philadelphia: Center for Cur-

NOTES

riculum Development, 1972); S. D. Krashen, "Formal and

Informal Environments in Language Acquisition and Lan-

guage Learning," TESOL Quarterly, 10 (1976), pp. 157-68.

1These quotations have been collected by counselors at

12S. D. Krashen, "The Input Hypothesis," Current Issues

the Learning Skills Center at the University of Texas,

in Bilingual Education: Georgetown University Round Table on

Austin. Languages and Linguistics, ed. J. E. Alatis (Washington:

Georgetown Univ. Press, 1980), pp. 168-80; H. Dulay,

2C. D. Spielberger, Manualfor the State-Trait Anxiety Inven-

tory (Form Y) (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists M. Burt & S. Krashen, Language Two (New York: Oxford

Press, 1983). Univ. Press, 1982).

3S. Tobias, Overcoming Math Anxiety (Boston: Houghton 13J. C. McCroskey, "Oral Communication Apprehen-

Mifflin, 1978); F. C. Richardson & R. L. Woolfolk, sion: A Summary of Recent Theory and Research," Human

"Mathematics Anxiety," Test Anxiety: Theory, Research and Communication Research, 4 (1977), pp. 78-96.

Application, ed. I. G. Sarason (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 14The practice in suggestopedia of providing students new

1980), pp. 271-88; J. V. Mallow, Science Anxiety (New York: target language identities may also capitalize on this phe-

Thomond, 1981). nomenon.

4C. A. Curran, Counseling-Learning in Second Languages 15E. M. Gordon & S. B. Sarason, "The R

(Apple River, IL: Apple River, 1976); E. Stevick, Language tween 'Test Anxiety' and 'Other Anxieties'

Teaching.: A Way and Ways (Rowley, MA: Newbury House, sonality, 23 (1955), pp. 317-23; Test Anxiety.

1980); A. Z. Guiora, "The Dialectic of Language Acquisi- andApplication, ed. I. G. Sarason (Hillsdal

tion," An Epistemology for the Language Sciences, ed. A. Z. 1980).

Guiora, Language Learning, 33 (1983), p. 8. 16D. Watson & R. Friend, "Measurement of Social-

5T. Scovel, "The Effect of Affect; A Review of the Anxiety Evaluative Anxiety,"Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol-

Literature," Language Learning, 28 (1978), p. 132. ogy, 33 (1969), pp. 448-51.

6H. H. Kleinmann, "Avoidance Behavior in Adult 17E. K. Horwitz, "Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety

Second Language Learning," Language Learning, 27 (1977),Scale," unpubl. manuscript, Univ. of Texas, Austin, 1983.

pp. 93-101; F. S. Steinberg & E. K. Horwitz, "The Effect 18See E. K. Horwitz, "Preliminary Evidence of the Reli-

of Induced Anxiety on the Denotative and Interpretive Con-ability and Validity of a Foreign Language Classroom

tent of Second Language Speech," TESOL Quarterly (in

Anxiety Scale" (forthcoming), for correlations between the

press). FLCAS and other specific anxieties and details on the con-

7j. A. Daly & M. D. Miller, "Apprehension of Writing struct validation process.

as a Predictor of Message Intensity," Journal of Psychology, 19See I. R. McCoy, "Means to Overcome the Anxieties

89 (1975), pp. 175-77; J. A. Daly, "The Effects of Writing of Second Language Learners," Foreign Language Annals, 12

Apprehension on Message Encoding,"Journalism Quarterly, (1979), pp. 185-89, for a discussion of dealing with stu-

27 (1977), pp. 566-72. dent anxieties in the foreign language classroom. Tech-

8R. C. Gardner, R. Clement, P. C. Smythe & C. C. niques for teaching relaxation are included in Benson's The

Smythe, Attitudes and Motivation Test Battery, Revised Manual. Relaxation Response (New York: Morrow, 1973) and E.

Research Bulletin 15 (London, Ontario: Dept. of Jacobson, Progressive Relaxation (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago

Psychology, Univ. of Western Ontario, 1979). Press, 1938). Behavioral contracting is an anxiety reduc-

9R. C. Gardner, P. C. Smythe, R. Clement & L. Gliks- tion method for students having difficulty attending to the

man, "Social and Psychological Factors in Second Language learning task. The student agrees to spend a specific amount

Acquisition," Canadian Modern Language Review, 32 (1976), of time on a task, such as going to the language lab, and

pp. 198-213. then reports back to the teacher on her or his success.

'0E. K. Horwitz, "What ESL Students Believe About 20When an anxiety reaction is both specific and severe,

Language Learning," unpubl. paper presented at the psychologists typically use the term "phobia."

TESOL Annual Meeting, Houston, March 1984. 21F. C. Richardson & R. L. Woolfolk (note 3 above).

11S. J. Savignon, Communicative Competence.: An Experiment

This content downloaded from

190.164.218.83 on Mon, 24 Oct 2022 22:24:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Horwitzetal 1986 FLClassroom Anxiety ScaleDocument9 pagesHorwitzetal 1986 FLClassroom Anxiety ScalepmacgregNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Classroom AnxietDocument9 pagesForeign Language Classroom AnxietjuliNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Author (S: Related PapersDocument10 pagesForeign Language Classroom Anxiety Author (S: Related Papersjohn huntNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety PDFDocument9 pagesForeign Language Classroom Anxiety PDFsolsticeangelNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety: Elaine K. Horwitz, Michael B. Horwitz, and Joann CopeDocument8 pagesForeign Language Classroom Anxiety: Elaine K. Horwitz, Michael B. Horwitz, and Joann CopeSara BataNo ratings yet

- Low Anxiety ClassroomDocument15 pagesLow Anxiety ClassroomStuti AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Students' Speaking Anxiety in EFL ClassroomDocument8 pagesStudents' Speaking Anxiety in EFL ClassroomIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Horwitz 1988 L2 Beliefsabout Lang LearningDocument13 pagesHorwitz 1988 L2 Beliefsabout Lang LearningpmacgregNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Second Language Acquisition: Teacher: Mirna Quintero Student: Francisco de BarnolaDocument15 pagesFactors Affecting Second Language Acquisition: Teacher: Mirna Quintero Student: Francisco de BarnolaSafaa Mohamed Abou KhozaimaNo ratings yet

- Gregersen Horwitz 2002Document10 pagesGregersen Horwitz 2002Júlia BánságiNo ratings yet

- Listening Anxiety in Iranian EFL Learners - Serraj 2015Document8 pagesListening Anxiety in Iranian EFL Learners - Serraj 2015Lê Hoài DiễmNo ratings yet

- Language Anxiety Variables and Their Negative Effects On SLA: A Psychosocial Reality in BangladeshDocument9 pagesLanguage Anxiety Variables and Their Negative Effects On SLA: A Psychosocial Reality in BangladeshSouvik BaruaNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Students PerspectiveDocument15 pagesAn Investigation of Students PerspectivePaung PwarNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Introduction Part of A Research ProposalDocument7 pagesAnalyzing The Introduction Part of A Research ProposalJustDarkeyMonNo ratings yet

- 110-Article Text-221-1-10-20170908Document7 pages110-Article Text-221-1-10-20170908Arta CurriNo ratings yet

- English Language Anxiety Among Young Learners: A Grounded TheoryDocument13 pagesEnglish Language Anxiety Among Young Learners: A Grounded TheoryDONA F. CANDANo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Students PerspectiveDocument15 pagesAn Investigation of Students PerspectiveRoffi ZackyNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Is An Emotion That Affects Every Person. Multiple Factors Can Drive A Person To ExperienceDocument54 pagesAnxiety Is An Emotion That Affects Every Person. Multiple Factors Can Drive A Person To ExperienceRehan BalochNo ratings yet

- Literature Review - Learning ToolDocument10 pagesLiterature Review - Learning Tooldulce crissNo ratings yet

- Learner VariablesDocument46 pagesLearner VariablesMohamed bouizyNo ratings yet

- Language Anxiety Among English Studnets in LibyaDocument23 pagesLanguage Anxiety Among English Studnets in LibyaTemzraaMusa100% (2)

- Students Psychological Factors in Sla A Dillema FDocument7 pagesStudents Psychological Factors in Sla A Dillema FJhona Mae CortesNo ratings yet

- 6 PDFDocument9 pages6 PDFSetia BriliantNo ratings yet

- A. Situation Analysis: Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College Graduate SchoolDocument2 pagesA. Situation Analysis: Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College Graduate SchoolChanel S. AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Sy Tamco, Albyra Bianca R. (2021) - An Assessment of English Language Anxiety Among SHS Students and Its Effect On Their Academic AchievementDocument8 pagesSy Tamco, Albyra Bianca R. (2021) - An Assessment of English Language Anxiety Among SHS Students and Its Effect On Their Academic AchievementAlbyra Bianca Sy TamcoNo ratings yet

- AFFECTIVE FACTORS-Group 6Document13 pagesAFFECTIVE FACTORS-Group 6lissa de los santosNo ratings yet

- And Strategies: Language Learning StylesDocument8 pagesAnd Strategies: Language Learning StylesHenry OsborneNo ratings yet

- Eelt0988Document8 pagesEelt0988Cristian Páez RosalesNo ratings yet

- Quero Soria Barrozo DulatreDocument48 pagesQuero Soria Barrozo DulatreLolita QueroNo ratings yet

- Phase 2 - Juan Diego Arias VillamizarDocument7 pagesPhase 2 - Juan Diego Arias VillamizarJuan Diego AriasNo ratings yet

- Cor Yell 2009Document22 pagesCor Yell 2009munaNo ratings yet

- Paola Montero Martinez Group 28 SLA Assignment: February 27, 2011Document8 pagesPaola Montero Martinez Group 28 SLA Assignment: February 27, 2011Daniel Vilches FuentesNo ratings yet

- A Situated Approach To The Understanding of Elusive Foreign Language Classroom AnxietyDocument19 pagesA Situated Approach To The Understanding of Elusive Foreign Language Classroom AnxietyAhmet Gökhan BiçerNo ratings yet

- Sec Unit 2Document11 pagesSec Unit 2dianaNo ratings yet

- Second Language Lexical Acquisition: The Case of Extrovert and Introvert ChildrenDocument10 pagesSecond Language Lexical Acquisition: The Case of Extrovert and Introvert ChildrenPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTION OF LINGUISTICS PsycholinguisticsDocument10 pagesINTRODUCTION OF LINGUISTICS PsycholinguisticsRevanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877042813035763 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S1877042813035763 MainDany PrayogaNo ratings yet

- Speaking Anxiety in A Foreign Language Classroom in KazakhstanDocument9 pagesSpeaking Anxiety in A Foreign Language Classroom in KazakhstanDesnitaNo ratings yet

- When Learning Disabilities Create Teaching DifficultiesDocument2 pagesWhen Learning Disabilities Create Teaching DifficultiesRubens RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Acquisition With Social Immersion A New Language For A New SelfDocument34 pagesForeign Language Acquisition With Social Immersion A New Language For A New SelfYann NemboNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in Learning English As A Second Language at A Tertiary Stage Causes and SolutionsDocument20 pagesAnxiety in Learning English As A Second Language at A Tertiary Stage Causes and SolutionsAuliaurrahmah100% (1)

- Teaching by Principles: Group 1Document32 pagesTeaching by Principles: Group 1Dwi Septiana PutriNo ratings yet

- The Teachers Role in Reducing Learners' Anxiety in Second Language ProductionDocument10 pagesThe Teachers Role in Reducing Learners' Anxiety in Second Language ProductionQuennie Mae DianonNo ratings yet

- Pananaliksik Kabanata 1 3Document30 pagesPananaliksik Kabanata 1 3John Andrei DavidNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience of Foreign Languages PDFDocument8 pagesNeuroscience of Foreign Languages PDFmartivolaNo ratings yet

- First Language Acquisition: Psychological Considerations and EpistemologyDocument7 pagesFirst Language Acquisition: Psychological Considerations and EpistemologySalsabila SajidaNo ratings yet

- Theories in SLADocument6 pagesTheories in SLAJahirtonMazo100% (1)

- UntitledDocument9 pagesUntitledMaria ElorriagaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in Language LearningDocument18 pagesAnxiety in Language LearningShirley MuñozNo ratings yet

- Iacozza-2017-What Do Your Eyes Reveal About YoDocument10 pagesIacozza-2017-What Do Your Eyes Reveal About YoMonica LinNo ratings yet

- CH3 Factors Affecting 2nd LG Learning - Lightbown & Spada, 1999Document12 pagesCH3 Factors Affecting 2nd LG Learning - Lightbown & Spada, 1999Karen Banderas ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Unidad No.: Personality FactorsDocument14 pagesUnidad No.: Personality FactorsMETAMORFOSIS YAPNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Reading AnxietyDocument18 pagesForeign Language Reading AnxietyNathan ChhakchhuakNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Linguistics: Vyvyan EvansDocument13 pagesCognitive Linguistics: Vyvyan Evanshoggestars72No ratings yet

- Oficial-Proposal-Action ResearchDocument3 pagesOficial-Proposal-Action ResearchRoyce DivineNo ratings yet

- IAR, Vol.1, Issue 1, 1-12Document12 pagesIAR, Vol.1, Issue 1, 1-12International Academic ReviewNo ratings yet

- Psycho 4Document6 pagesPsycho 4astutiNo ratings yet

- Material - de - Lectura - Obligatorio - Unidad - 1 Adquisicion PDFDocument14 pagesMaterial - de - Lectura - Obligatorio - Unidad - 1 Adquisicion PDFCristina CastilloNo ratings yet

- SRAZ 62 KotulaDocument18 pagesSRAZ 62 KotulaKrzysztof KotułaNo ratings yet

- The Economist Brexit and English NationalismDocument2 pagesThe Economist Brexit and English Nationalismvalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- Postmodifier Adverbial Clause of Place: Where Roman Soldiers With Their Families After They From The ArmyDocument2 pagesPostmodifier Adverbial Clause of Place: Where Roman Soldiers With Their Families After They From The Armyvalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledvalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- LCL319 - Microteaching TemplateDocument2 pagesLCL319 - Microteaching Templatevalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- Mobile Technologies For English LanguageDocument9 pagesMobile Technologies For English Languagevalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- Hyon 1996 Genre in Three Traditions - Implications For ESLDocument31 pagesHyon 1996 Genre in Three Traditions - Implications For ESLvalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- Anxiety ArticleDocument11 pagesAnxiety Articlevalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- The Negative Effect of Smartphone UseDocument25 pagesThe Negative Effect of Smartphone Usevalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- 4 TQ PCyl MXV RDocument337 pages4 TQ PCyl MXV Rdjamel100% (3)

- Learning DifficultiesDocument9 pagesLearning DifficultiespwmarinelloNo ratings yet

- Zuniga Speech Act (Stylistics) - ENG14NDocument10 pagesZuniga Speech Act (Stylistics) - ENG14NZarah ZunigaNo ratings yet

- Chipaya Alphabet7Document4 pagesChipaya Alphabet7Flor FJNo ratings yet

- English Unit: Narratives: Year Level/class 6/7 Number of Lessons 5 TopicDocument8 pagesEnglish Unit: Narratives: Year Level/class 6/7 Number of Lessons 5 Topicapi-525093925No ratings yet

- SLA Research Nourishing Language Teaching Practice.Document7 pagesSLA Research Nourishing Language Teaching Practice.SaSa Oviedo67% (3)

- Semis Finals Lecture in Purposive Communication Online Classes 2nd Sem 2020 NoDocument23 pagesSemis Finals Lecture in Purposive Communication Online Classes 2nd Sem 2020 NoXenonexNo ratings yet

- DLL - ENGLISH 3 - Q2 - C3 - Consonant BlendsDocument8 pagesDLL - ENGLISH 3 - Q2 - C3 - Consonant BlendsAnnaliza MayaNo ratings yet

- The Sixty Year DreamDocument38 pagesThe Sixty Year Dreamhecyanrebeti78% (9)

- Kid's Box 3: Lesson ProgrammeDocument177 pagesKid's Box 3: Lesson ProgrammeДоктор ЮлияNo ratings yet

- Leadership Essay Assignment 2020Document3 pagesLeadership Essay Assignment 2020Cyrus WanjohiNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in English 9: (Using Adverbs in Narration)Document8 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in English 9: (Using Adverbs in Narration)Faith Malinao100% (1)

- Lesson Plan EnglishDocument3 pagesLesson Plan EnglishMuhammad BaihaqiNo ratings yet

- الترجمة القانونيةDocument270 pagesالترجمة القانونيةMahmoud El-Baz92% (12)

- AP Language Rhetorical Strategies and TermsDocument3 pagesAP Language Rhetorical Strategies and TermsSharon Xu100% (1)

- (Don't Bother To Memorize The Technical Terms Used!) : Three Places Two NumbersDocument5 pages(Don't Bother To Memorize The Technical Terms Used!) : Three Places Two NumbersTestNo ratings yet

- Lexicology Unit 8Document24 pagesLexicology Unit 8Business EnglishNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7 Summary WritingDocument24 pagesLecture 7 Summary WritingYee KatherineNo ratings yet

- Ed 3508 Scratch Lesson Plan 1Document5 pagesEd 3508 Scratch Lesson Plan 1api-697852119No ratings yet

- Twi Linguistics BookDocument78 pagesTwi Linguistics BookOya Soulosophy100% (4)

- Secondary: CatalogueDocument84 pagesSecondary: CatalogueAyelén HawryNo ratings yet

- American English Language TrainingDocument222 pagesAmerican English Language Trainingshahsa2011No ratings yet

- DLL - English 4 - Q4 - W2Document6 pagesDLL - English 4 - Q4 - W2EM GinaNo ratings yet

- Font Combinations That Work Together Well - Website Design West MidlandsDocument7 pagesFont Combinations That Work Together Well - Website Design West MidlandsAndandoonNo ratings yet

- Why The Sun and The Moon Live in The SkyDocument21 pagesWhy The Sun and The Moon Live in The SkyHibha MoosaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - 10thgrade - 1stseptember - MaluendaPaula.Document11 pagesLesson Plan - 10thgrade - 1stseptember - MaluendaPaula.Paula Maluenda TorresNo ratings yet

- English V Quarter 2 - Week 3Document2 pagesEnglish V Quarter 2 - Week 3Azhia KamlonNo ratings yet

- English Grade I Learning CompetenciesDocument3 pagesEnglish Grade I Learning CompetenciesSheryl Silang100% (1)

- Assessment 1 Marking Rubric HRMG 703 Semester 1 2021Document2 pagesAssessment 1 Marking Rubric HRMG 703 Semester 1 2021Dylan TaddumNo ratings yet

- Jamboree Education IELTS Study PlanDocument6 pagesJamboree Education IELTS Study PlanTHẮNG HỒ HỮUNo ratings yet