Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jesse Ababon Educ 201 Insights November 18, 2022

Uploaded by

Catherine AbabonCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jesse Ababon Educ 201 Insights November 18, 2022

Uploaded by

Catherine AbabonCopyright:

Available Formats

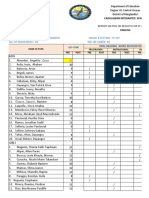

St.

Catherine’s College

6019 Carcar City, Cebu

Department of Graduate School

Educ 201 (Philo. of Education)

AY 2022-2023 First Semester

Name: Jesse B. Ababon Date: November 18, 2022

Professor: Letitia Florido Time; 11:30-2:30 P.M. (Saturday)

Problems Of Philippine Education

It is uncommon to hear college teachers decry the quality of students that come to

them. They lament the students’ inability to construct a correct sentence, much less a

paragraph. Private schools have been assailed as profit-making institutions turning out

half-baked graduates who later become part of the nation’s educated unemployed. All

these are indications of the poor quality of education.

The major problem of the tertiary level is the large proportion of the so called

“mismatch” between training and actual jobs, as well as the existence of a large group

of educated unemployed or underemployed. The literature points out that this could be

the result of a rational response to a dual labor market where one sector is import-

substituting and highly-protected with low wages. Graduates may choose to “wait it out”

until a job opportunity in the high paying sector comes.

To address this problem, it is suggested that leaders in business and industry should be

actively involved in higher education. Furthermore, a selective admission policy should

be carried out; that is, mechanisms should be installed to reduce enrolment in

oversubscribed programs and promote enrolment in undersubscribed ones.

It is in the educational sector where the concept of globalization is further refined and

disseminated. It comes in varied forms as “global competitiveness,” “the information

highway,” “the Third Wave Theory,” “post modern society,” “the end of history,” and

“borderless economy.”

The so-called Philippines 2000 was launched by the Philippine government to promote

“global competitiveness,” Philippine Education 2000 carried it to effect through training

of more skilled workers and surplus Filipino human power for foreign corporations to

reduce their cost of production.

The Philippines, including its educational sector, is controlled by US monopoly capital

through loan politics. This task is accomplished by the IMF, the World Bank and a

consortium of transnational banks, called the Paris Club, supervised by the WB. The

structural adjustments as basis for the grants of loans, basically require liberalization,

deregulation and privatization in a recipient country.

As transplanted into the educational sector, deregulation is spelled reduced

appropriation or reduced financial assistance to public schools through so called fiscal

autonomies; privatization and liberalization is spelled commercialized education or

liberalization of governments’ supervision of private schools and privatize state colleges

and universities.

The WB-IMF and the Ford Foundation have earmarked $400M for Philippine education.

These loans financed the Educational Development Project (EDPITAF) in 1972; the

Presidential Commission to Survey Philippine Education (PCSPE) in 1969; the Program

for Decentralized Educational Development (PRODED) in 1981-1989. As pointed out by

many critics, “the massive penetration of WB-IMF loans into the Philippine Educational

System has opened it wide to official and systematic foreign control, the perpetuation of

US and other foreign economic interest, and to maximize the efficiency of exploiting

Philippine natural resources and skilled labor.”

A number of studies and fact-finding commissions such as the Sibayan and Gonzales

Evaluation (1988), the Presidential Commission to Survey Philippine Education

(PCSPE, 1969), and the Congressional Commission on Education (EDCOM, 1991-

1992) have pointed out that the problems of Philippine education are the problems of

quality and political will

You might also like

- Jesse Ababon Thesis ProposalDocument12 pagesJesse Ababon Thesis ProposalCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Updated 11-12-2022 CADULAWAN-IS-PRE-TEST-PHIL-IRI-2022-2023Document4 pagesUpdated 11-12-2022 CADULAWAN-IS-PRE-TEST-PHIL-IRI-2022-2023Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Qra Form Template KS2 Grades 4 6Document79 pagesQra Form Template KS2 Grades 4 6Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Reading Performance of Grades 5 and 6 LeDocument21 pagesReading Performance of Grades 5 and 6 LeCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- English 4 q1 St4Document2 pagesEnglish 4 q1 St4Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Catherine Ababon SEMI FINAL-ASSIGNMENT FOR EDUC 201Document2 pagesCatherine Ababon SEMI FINAL-ASSIGNMENT FOR EDUC 201Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Catherine F. Ababon Thesis ProposalDocument12 pagesCatherine F. Ababon Thesis ProposalCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- MathDocument3 pagesMathCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- BACAY ES 2022 SF Inventory Classroom Blank Form 1 1Document2 pagesBACAY ES 2022 SF Inventory Classroom Blank Form 1 1Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

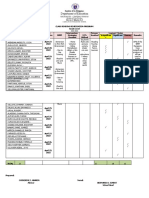

- Competency Checklist in - : (Already Printed Per Grade Per Subject Per Quarter)Document2 pagesCompetency Checklist in - : (Already Printed Per Grade Per Subject Per Quarter)Catherine Ababon0% (1)

- CADULAWAN ES CONSOLIDATED FORM-SLM-Production-and-Distribution-2020Document41 pagesCADULAWAN ES CONSOLIDATED FORM-SLM-Production-and-Distribution-2020Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- FilipinoDocument2 pagesFilipinoCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Educ201 Insight Jesse Ababon Oct. 8,2022Document2 pagesEduc201 Insight Jesse Ababon Oct. 8,2022Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Epp IctDocument3 pagesEpp IctCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 Self-Learning ModuleDocument15 pagesGrade 4 Self-Learning ModuleCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Revised CIS SPPD 2020 23Document3 pagesRevised CIS SPPD 2020 23Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 Solid Waste Management Teachers - GuideDocument31 pagesGrade 4 Solid Waste Management Teachers - GuideCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- CADULAWAN ES Progress-Monitoring-Tracking-Report-for-SLM-Production-and-Distribution-2020 (Aug.24,2020)Document2 pagesCADULAWAN ES Progress-Monitoring-Tracking-Report-for-SLM-Production-and-Distribution-2020 (Aug.24,2020)Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- GR. FOUR JOY - School Reading Remediation ProgramDocument4 pagesGR. FOUR JOY - School Reading Remediation ProgramCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- CADULAWAN ES Cebu-Province-SLM-Status-Report (Pdated Aug.24,2020Document5 pagesCADULAWAN ES Cebu-Province-SLM-Status-Report (Pdated Aug.24,2020Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- CATHERINE ABABON Vision-Test-Adviser-ReportDocument2 pagesCATHERINE ABABON Vision-Test-Adviser-ReportCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 Joy Wellness Narrative Report 2022-2023Document2 pagesGrade 4 Joy Wellness Narrative Report 2022-2023Catherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- MCES Gr.3 EGRA Pre TEST Final School ConsolidationDocument2 pagesMCES Gr.3 EGRA Pre TEST Final School ConsolidationCatherine Ababon100% (1)

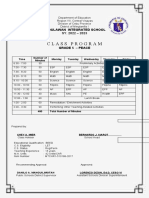

- Class Program Elem With Edited BORDERDocument1 pageClass Program Elem With Edited BORDERCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- 4 Joy English Pretest Phil IriDocument4 pages4 Joy English Pretest Phil IriCatherine AbabonNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Banking & Financial Awareness Current AffairsDocument12 pagesBanking & Financial Awareness Current AffairsPraveen KumarNo ratings yet

- World Bank ReportDocument14 pagesWorld Bank Reportaditya_erankiNo ratings yet

- Bibliography ThailandDocument15 pagesBibliography Thailandcranberryth_esauceNo ratings yet

- M1 - L1 - Intro To World and Phil AgricultureDocument7 pagesM1 - L1 - Intro To World and Phil AgricultureHerman Inac ColonganNo ratings yet

- Ecowap: A Fragmented PolicyDocument26 pagesEcowap: A Fragmented PolicyOxfamNo ratings yet

- Environmental Performance Indicators: A Second Edition NoteDocument50 pagesEnvironmental Performance Indicators: A Second Edition NoteMuthuswamyNo ratings yet

- IMF and World Bank in Need of More Modern Forecasting MethodsDocument5 pagesIMF and World Bank in Need of More Modern Forecasting MethodsBrent M. Eastwood, PhDNo ratings yet

- Alandurseweragetreatmentplantproject Pppmodel 190927110958 PDFDocument15 pagesAlandurseweragetreatmentplantproject Pppmodel 190927110958 PDFTran Binh MinhNo ratings yet

- Green Infrastructure Finance Framework ReportDocument88 pagesGreen Infrastructure Finance Framework ReportPablo Fernando Ortiz PinellNo ratings yet

- McKinsey Report On SME FinancingDocument60 pagesMcKinsey Report On SME Financingapritul3539100% (1)

- Concept Project Information Document PID Tanzania Secondary Education Quality Improvement Project SEQUIP P170480Document7 pagesConcept Project Information Document PID Tanzania Secondary Education Quality Improvement Project SEQUIP P170480tgrrwccj98No ratings yet

- Gaylord Booto Kabongo GUI ProfileDocument3 pagesGaylord Booto Kabongo GUI ProfileGlobal Unification InternationalNo ratings yet

- Private-Sector Provision of Health Care in The Asia-Pacific Region: A Background Briefing On Current Issues and Policy ResponsesDocument18 pagesPrivate-Sector Provision of Health Care in The Asia-Pacific Region: A Background Briefing On Current Issues and Policy ResponsesNossal Institute for Global HealthNo ratings yet

- TOR - BBMA DED and Supervision ConsultantDocument54 pagesTOR - BBMA DED and Supervision ConsultantRachmat HidayatNo ratings yet

- The Black Agenda, Updated From 1992 in 2001 by Naiwu OsahonDocument17 pagesThe Black Agenda, Updated From 1992 in 2001 by Naiwu OsahonJAHMAN7No ratings yet

- Law AssignmentDocument4 pagesLaw AssignmentMoe EcchiNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Definitions - Globalisation - Edexcel Geography A-LevelDocument3 pagesGlossary of Definitions - Globalisation - Edexcel Geography A-LevelSashiNo ratings yet

- Aid, Conditionality and Debt in AfricaDocument12 pagesAid, Conditionality and Debt in AfricaDaniel MorganNo ratings yet

- Distribution PolicyDocument93 pagesDistribution PolicysdmaityNo ratings yet

- CV Mukul G. AsherDocument49 pagesCV Mukul G. AsherabraNo ratings yet

- 9-2 International Relief and Development Awarded World Bank Contract For Afghanistan Monitoring and ComplianceDocument2 pages9-2 International Relief and Development Awarded World Bank Contract For Afghanistan Monitoring and ComplianceInternational Relief and DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Advertisement For Calling Applications For Appointment of Individual Consultants (Ic) - Full Time On Contractual BasisDocument13 pagesAdvertisement For Calling Applications For Appointment of Individual Consultants (Ic) - Full Time On Contractual BasisAr. Kumar AnilNo ratings yet

- Computerised Accounting Information Systems Lessons in State-Owned Enterprise in Developing Economies PDFDocument23 pagesComputerised Accounting Information Systems Lessons in State-Owned Enterprise in Developing Economies PDFjcgutz3No ratings yet

- Quiz1Document25 pagesQuiz1Jishnu M RavindraNo ratings yet

- The Global Interstate System#finalDocument3 pagesThe Global Interstate System#finalNeriza PonceNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World MODULE 1Document24 pagesContemporary World MODULE 1Tracy Mae Estefanio100% (2)

- AWP Position Paper (Pakistan)Document33 pagesAWP Position Paper (Pakistan)Arham MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Annex A: Technical Application Template: Amanat Afghanistan USAID CONTRACT NUMBER AID-306-H-17-00003Document34 pagesAnnex A: Technical Application Template: Amanat Afghanistan USAID CONTRACT NUMBER AID-306-H-17-00003wafiullah sayedNo ratings yet

- RBI ESI PDF 2 - Economic History of IndiaDocument29 pagesRBI ESI PDF 2 - Economic History of Indiamanshisinghrajput29No ratings yet

- Cambodia Standard of AuditDocument76 pagesCambodia Standard of AuditChanrin MaoNo ratings yet