Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shelter For Storm in Philliphine

Shelter For Storm in Philliphine

Uploaded by

Weifeng HeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Shelter For Storm in Philliphine

Shelter For Storm in Philliphine

Uploaded by

Weifeng HeCopyright:

Available Formats

POLLACK PERIODICA

An International Journal for Engineering and Information Sciences

DOI: 10.1556/606.2020.15.2.20

Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 221–232 (2020)

www.akademiai.com

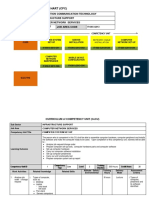

OCHO BALAY: DESIGN OF A PERMANENT

TYPHOON SHELTER FOR THE RURAL AREAS IN

THE PHILIPPINES

1

Rowell Ray SHIH*, 2 Danilo RAVINA

1,2

Department of Architecture, School of Architecture, Fine Arts and Design

University of San Carlos, Cebu City, Cebu, Philippines

e-mail: 1drowellshih@yahoo.com, 2dravina@yahoo.com

Received 5 November 2019; accepted 18 January 2020

Abstract: In 2013 Typhoon Haiyan, devastated several portions of the Philippines, which

resulted in more than 7,000 deaths and thousands made homeless. The aim of this study is to

propose a design of a permanent shelter as a continuation of the I-Siguro Daan Transitional

Shelter, which was successfully deployed in 2014 and produce a transitional shelter prototype, for

the victims of typhoon Haiyan. In order to develop the methodological design of the Permanent

Shelter, the author presented several factors into consideration: the understanding how the rural

communities use the present I-Siguro Daan Transitional Shelter; to further develop and improve

the interior space of the shelter; to propose a better roof design; and to design a sustainable toilet

and kitchen area for the users. Methodologies used in the study were the use of surveys and

interactions with the community, which focuses on gaining the understanding how the

communities use the present I-Siguro Daan Transitional Shelter. By exploring related case

studies and literatures, site surveys and consultations with different groups, the resulting

Permanent Shelter will a promising solution for improving the lives of the communities while

also providing groundwork for future shelter related studies.

Keywords: Permanent shelters, Emergency shelters, Post disaster housing

1. Introduction

The Philippines, sitting on the ‘Pacific Ring of Fire’, is a country that frequently

faces various natural disasters [1], [2]. In 2013, typhoon Haiyan devastated the central

Visayas, killing more than 7,000 people, mostly in the rural communities and

*

Corresponding Author

HU ISSN 1788–1994 © 2020 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

222 R. R. SHIH, D. RAVINA

shorelines. More than 360,000 houses in Eastern Visayas were totally destroyed by

Super Typhoon Haiyan, thus highlighting the importance of typhoon-resistant housing.

The Philippines is a rapidly developing country, which experiences the problem of rapid

family formation, poor housing and an increased scarcity of land. Housing shortage is

particularly serious in the urban areas, combined with the rising cost of construction [3].

Traditional housing made from locally available materials is the only form of housing

available to the poorest families and lacks any typhoon resistant features. These

traditional houses can be found in the coastal and rural areas of the country and since

they are weak, many of them are destroyed annually. The importance of and need for

disaster resilient permanent shelters are increasing globally, as no nation is immune

from the effects of natural disasters. Permanent Shelters are usually progressed from

transitional shelters and from a core shelter [4]-[9]. This paper proposes to design and

develop a Typhoon permanent shelter as a continuance of the previous original work of

the I-Siguro Daan Transitional Shelter proposed by the authors [10]. The configuration

of the I-Siguro Daan (Fig. 1) has a rectangular floor plan of 4.7 m × 2.4 m with a total

height of 3.5 m, measured up to the apex of the roof. The proposed typhoon shelter must

require the same or close to the minimum on-site construction activities, workers and

equipment while using the available local resources. Thus, the aim of the study is to

provide a transition to the permanent shelter design. In this paper, the authors

conceptualize, design and develop a permanent typhoon shelter for a single family

based upon the original groundwork of the I-Siguro Daan Transitional Shelter. The

shelter must likewise be affordable without sacrificing the structural integrity of the

project and must be culturally sensitive to the Filipino community.

Fig. 1. Exterior of the I-Siguro Daan transitional shelter

2. Methodology

The process of community participation was used in the final design of the proposed

permanent shelter. This is significant because the re-housing process involves major

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

OCHO BALAY: DESIGN OF A PERMANENT TYPHOON SHELTER 223

change and requires a profound restructuring of daily life of the community [11]. Field

research, interviews and surveys were being used as one of the basis for the final of the

shelter. In this methodology, the author gathered data analysis from the beneficiaries of

the I-Siguro Daan Shelters, particularly from the Northern part of Cebu after typhoon

Haiyan. Furthermore, field research and surveys were being done by the author from the

beneficiaries of the permanent socialized housing units. The main objective of the

surveys and interviews was the user satisfaction rate and use of the shelters by the

beneficiaries. The results of the surveys and interviews resulted in the importance of

better shelters for the Filipino. Data also showed that the average number of families

that occupy these units’ number to five, which includes the children and in some cases,

the extended family members. These family members are contented with the 28 square

meters provided by each housing unit, although most of the users would want to

socialize with their friends and neighbors outside their home. The need to socialize and

interact with different friends and family members is a trait that most of the Filipino

family adheres to. There is a need to also have a large open space for other extra-

curricular activities that may involve other members of the family. The family members

also find the need to make their own small store business. Majority of the beneficiaries

also raised poultry and livestock. Although these animals are being regulated by the

members of the community, they are very useful especially when families have a hard

time buying their own food. The findings of the survey resulted in the following

concerns by the beneficiaries:

i) Need for more open spaces;

ii) Flood prevention system;

iii) Spaces for poultry and plants;

iv) Affordable housing;

v) Improved indoor ventilation;

vi) Expandable indoor space; and

vii) Capacity to develop the shelter when their financial status improves over time.

The results of these surveys will therefore be one of the design considerations of the

proposed typhoon shelter that is presented in this study.

3. Design of the Ocho Balay

In this study, the authors present the Ocho Balay, which means 8 Houses. The name

of the shelter is based on the plan and the design of eight sided walls, which the shelter

is known for. The proposed unit was also designed after an extensive analysis of local

architecture while respecting the local traditions and culture so as to enhance the

feasibility of replication and maintenance of the shelters by the beneficiaries. Thus, easy

accessibility and economic materials are an important factor when constructing

permanent structures [12]. It is therefore important to analyze the context of the location

of the shelters. The shelter design must be flexible enough on the use of local

construction materials and allow replacement with alternatives. The basic materials used

in the shelter are:

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

224 R. R. SHIH, D. RAVINA

1) Coco Lumber;

2) Amakan and

3) Bamboo Splits.

For the exterior framing, Coco Lumber was used because it is a common hardwood

substitute from the coconut palm trees found in the Philippines (Fig. 1). However,

4”x4” for post may be difficult to come by, so the basic dimension to be used shall be

2”x4” and 2”x6” with lengths at 8’ and 10’.

As for the walls, Amakan offers a cheap yet durable alternative. The use of concrete

board and plywood can also be used in the future when the families are able to upgrade

their economic status. Simplicity in design was an important design consideration

because simple shelters for the commons are much easier to communicate. The shelter

has fewer moving parts, fewer interactions, and fewer opportunities for failure.

Strengthening individual identity and sense of community was also a design

consideration. The shelter design was based on the popular traditional Filipino House,

the Bahay Kubo. It employs passive cooling principles and has ample natural light

during the day. Furthermore, the United Architects of the Philippines recommends a

four sided hip roof (Fig. 2) because it is more streamlined and sealed against buffeting

winds. Thus, use of four sided roofs was being proposed in this design.

The design of the shelter also allows for incremental development. The concept of

incremental housing is based on the capacity to adapt the house model to the

development of the family [13]. The indication of incremental development is typically

associated with developing countries, where access to institutional housing finance is

limited or unavailable, particularly for low-income households. The main structural

characteristics of the proposed shelter is the use of the Bent Structure which is a

transverse rigid frame similar to that of the three-hinged arches [14], [15], [16]. The

Bent Structure structural system is, made of coco lumber (Fig. 3), which resulted in

slanted walls on the exterior.

Fig. 2. Coco Lumber exterior framing

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

OCHO BALAY: DESIGN OF A PERMANENT TYPHOON SHELTER 225

Fig. 3. Proposed four sided hip roof

The slanted walls (Fig. 4, Fig. 5) will make the interior appear larger while

providing more storage. The sides can also be safely extendable in all directions when

the families improve their financial status in the future. This can also be seen as a

strategy for continuous growth and improvement. Work or improvements done on one

side can be easily upgraded on the other side in a more permanent way with a more

resistant material.

Fig. 4. Detail of the Bent Structure

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

226 R. R. SHIH, D. RAVINA

Fig. 5. The slanted walls of the shelter and corner wall (exposed)

The spaces of the interior of the shelter are divided into two parts:

1) Living Module; and the

2) Sleeping Module.

For Filipinos, these spaces encourage communal activity, which allows social

gatherings and activities [17]. As it can be seen in the plan, the walls are constructed of

breathable materials for better thermal comfort and allow views from the inside to the

outside while allowing natural cross ventilation (Fig. 6).

In order to allow cross ventilation and thermal comfort during the day, the elevated

floor is made up of fiber cement boards or bamboo stripes. Lockable windows made of

wooden shutters enhance the cross ventilation and thermal comfort while fascia boards

and short overhangs of the roof minimize the negative forces on the roof during a

typhoon. The roof is made up of GI Corrugated sheets on coco purlins and reinforced

with the traditional umbrella nails, which can help in securing the roof during a strong

typhoon. The height of the floor level is 900 mm but nevertheless can be adjusted

according to the site location (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). Depending on the site location and

potential hazards of the area, the height of the post can be adjusted, especially in flood

prone areas.

In terms of added function, the author proposed an outdoor toilet and kitchen. The

outdoor toilet and kitchen are designed with a reinforced concrete frame combined with

reinforced concrete slab, forming a safe box for occupants to shelter in case of extreme

typhoon. The slanted roof encourages rainwater harvesting for the families. Rainwater

can be collected for toilet use and/or for urban gardening systems. Rooftop rainwater

harvesting is the most common technique of rainwater harvesting for domestic

consumption. In rural areas, this is most often done at small-scale. Rainwater harvesting

can supplement water sources when they become scarce or are of low quality like

brackish groundwater or polluted surface water in the rainy season. This is simple, low-

cost technique that requires minimum specific expertise or knowledge and offers many

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

OCHO BALAY: DESIGN OF A PERMANENT TYPHOON SHELTER 227

benefits. Rainwater is collected on the roof and transported with gutters to a storage

reservoir, where it provides water at the point of consumption for the families. In this

design, the author proposed a rainwater harvesting system with the use of a simple PVC

container which is popular in the Philippines (Fig. 9).

Fig. 6. The living and sleeping module of the interior

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

228 R. R. SHIH, D. RAVINA

Fig. 7. Front elevation

Fig. 8. Longitudinal section

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

OCHO BALAY: DESIGN OF A PERMANENT TYPHOON SHELTER 229

Fig. 9. A simple PVC container for rainwater harvesting

Rainwater are collected in the gutter of the roof and then channeled down via pipes

to a plastic water container tank near the comfort room. Finally, as seen in the plans

(Fig. 10 and Fig. 11) building the toilet and kitchen with hollow blocks and reinforced

concrete will also provide opportunity to incorporate training program for masons and

thus improve the construction quality in the foreseeable future. Fig. 12 shows the

proposed exterior of the toilet and kitchen.

A scale model (Fig. 13) shows how the interior and exterior framings will be built.

In terms of cost, the estimated budget for each unit is US$ 1, 904.66 as of January 8,

2019 with a floor area of 19 square meters for a family of five. Making each unit

affordable will obviously allow for more housing unit to be built and therefore will

result in more beneficiaries having a shelter of their own.

Fig. 10. Floor plan of the toilet and kitchen

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

230 R. R. SHIH, D. RAVINA

Fig. 11. Front elevation of the toilet and kitchen

Fig. 12. Exterior perspective of the toilet and kitchen

4. Conclusion

Natural disasters continue to leave thousands of Filipino people homeless every

year, forcing them to seek refuge without any other alternatives. On many occasions, the

local government cannot cope with the affected families and therefore limiting their

resources. This study proposes a permanent typhoon shelter that is affordable and yet

can be easily upgraded. The main structural material used in the shelter is Coco Lumber,

which is very abundant in the Philippines. The proposed unit has a simple rectangular

building form with a hip roof for easy construction by the local workers. The short

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

OCHO BALAY: DESIGN OF A PERMANENT TYPHOON SHELTER 231

overhang design can effectively reduce the impacts of wind force that is the main cause

of damage to the roof structure during a typhoon.

Fig. 13. Study Scale Model showing the interior and exterior framings.

The author likewise recognizes the importance of the Slanted Wall Design, as applied to

the I-Siguro Daan Shelter series. The slanted walls will make the interior appear larger

while providing more storage. The unusable space where the walls meet the floor can be

turned into storage spaces. The house can also be expanded horizontally to have more

spaces if the need arises. The slanted roof encourages rainwater harvesting for the

families. Rainwater can be collected for toilet use and/or for urban gardening systems.

Building the toilet and kitchen with hollow blocks and reinforced concrete will also

provide job opportunities to the community. Finally, the shelter also offers a flexible

solution, which at the same time is moderate in cost. This shelter will hopefully be a

stepping stone on the journey towards a brighter future for the beneficiaries in the

Filipino’s pursuit of a better quality of life, especially after the traumatizing effects of a

natural disaster. As architects and designers, the application of innovation and creativity

plays an important role in the construction practices, which results in an efficient

methodology that can be replicated after natural disasters.

Acknowledgements

This work has been undertaken as part of a community project by the University of

San Carlos School of Architecture, Fine Arts, Republic of the Philippines and Design

and Marcel Breuer Doctoral School, Faculty of Engineering and Information

Technology, University of Pecs, Hungary.

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

232 R. R. SHIH, D. RAVINA

References

[1] Van Voorst R., Wisner B., Hellman J.,Nooteboom G. Introduction to the ‘risky everyday’,

Disaster Prevention and Management, Vol. 24, No, 4, 2015, pages 1-6.

[2] Wisner B., Blaikie P., CannonT., Davis J. At risk: natural hazards, people's vulnerability

and disasters, Routledge, 2005.

[3] Diacon D. Typhoon resistant housing in the Philippines: The core shelter project, Disasters,

Vol. 16, No. 3, 1992, pp. 266‒271.

[4] Quarantelli E. L. Patterns of sheltering and housing in US disasters, Disaster Prevention

and Managemen, Vol. 4, No. 3, 1995, pp. 43‒53.

[5] Wu J. Y., Lindell M. K. Housing reconstruction after two major earthquakes: The 1994

Northridge earthquake in the United States and the 1999 Chi‐Chi earthquake in Taiwan,

Disasters, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2004, pp. 63‒81.

[6] Johnson C., Lizarralde G., Davidson C. H. A systems view of temporary housing projects

in post‐disaster reconstruction, Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 24, No. 4,

2006, pp. 367‒-378.

[7] Johnson C. Impacts of prefabricated temporary housing after disasters: 1999 earthquakes in

Turkey, Habitat International, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2007, pp. 36‒52.

[8] Johnson C. Strategic planning for post‐disaster temporary housing, Disasters, Vol. 31,

No. 4, 2007, pp. 435‒458.

[9] Félix D., Branco J. M., Feio A. Temporary housing after disasters: A state of the art survey,

Habitat International, Vol. 40, 2013, pp. 136‒141.

[10] Ravina D., Shih R. R. A shelter for the victims of the Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines:

The design and methodology of construction, Pollack Periodica, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2017,

pp. 129‒139.

[11] Davidson C. H., Johnson C., Lizarralde G., Dikmen N., Sliwinski A. Truths and myths

about community participation in post-disaster housing projects, Habitat International,

Vol. 31, No. 1, 2007, pp. 100‒115.

[12] Ohlson S., Melich R. Designing and developing sustainable housing for refugee and

disaster communities, IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference, San Jose, CA,

USA, 10-13 October 2014, pp. 614‒619.

[13] Greene M., Rojas E. Incremental construction: a strategy to facilitate access to housing,

Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2008, pp. 89‒108.

[14] Benson T. Building the timber frame house: The revival of a forgotten craft, Simon and

Schuster, 1981.

[15] Bosher L., Dainty A. Disaster risk reduction and ‘built‐in ‘resilience: towards overarching

principles for construction practice, Disasters, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2011, pp. 1‒18.

[16] Faherty K. F., Williamson T. G. Wood engineering and construction handbook, McGraw-

Hill, 1998.

[17] Ravina D. V., Shih R. R. L., Medvegy G. Community architecture: the use of participatory

design in the development of a community housing project in the Philippines, Pollack

Periodica, Vol. 13, No. .2, 2018, pp. 207‒218.

Pollack Periodica 15, 2020, 2

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/14/22 11:41 AM UTC

You might also like

- Final Project ReportDocument65 pagesFinal Project ReportVikas Dalal75% (4)

- Solar Power Bank Using Old Laptop Batteries PDFDocument6 pagesSolar Power Bank Using Old Laptop Batteries PDFgggg jjjjNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesLiterature ReviewAravindSrivatsan74% (19)

- Retaining or Slough Wall (4 Foot High or Less) Ib P Bc2014 002Document2 pagesRetaining or Slough Wall (4 Foot High or Less) Ib P Bc2014 002tiger_lxfNo ratings yet

- Thonet - A Pioneer of Furniture History: ContentDocument9 pagesThonet - A Pioneer of Furniture History: ContentAle VillaNo ratings yet

- Take Off List - RevDocument58 pagesTake Off List - Revteeyuan0% (2)

- Conceptual Design of Nuclear-Geothermal Energy Storage Systems For Variable Electricity ProductionDocument184 pagesConceptual Design of Nuclear-Geothermal Energy Storage Systems For Variable Electricity Productionoxe70970No ratings yet

- S8 - 1st Periodical - Answer Key - Copy1Document7 pagesS8 - 1st Periodical - Answer Key - Copy1Jadilyn Rose SaturosNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Health TeachingDocument4 pagesNutrition Health TeachingFreisanChenMandumotanNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesLea YaonaNo ratings yet

- Handout3 PostDocument7 pagesHandout3 PostleandropessiNo ratings yet

- FS2 Ep4Document7 pagesFS2 Ep4Kent Bernabe100% (1)

- MagnetismDocument29 pagesMagnetismYoshiro YangNo ratings yet

- Magnet 1Document34 pagesMagnet 1Dina Mardiana100% (1)

- Maribago Resort vs. Dual, July 20, 2010Document3 pagesMaribago Resort vs. Dual, July 20, 2010gerielle mayoNo ratings yet

- The Historical Roots of Sociocultural TheoryDocument10 pagesThe Historical Roots of Sociocultural TheoryHarum marwahNo ratings yet

- Rowell Ray Lim Shih PHD 2019Document123 pagesRowell Ray Lim Shih PHD 2019hot bloodNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 4 Dec.06 PDFDocument41 pagesChapter1 4 Dec.06 PDFJohn Dominic Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Supreme Pupil Government Spgo Action Plan 2018 2019 RevisedDocument2 pagesSupreme Pupil Government Spgo Action Plan 2018 2019 RevisedPatson OpidoNo ratings yet

- ANAPHY Lec Session #17 - SAS (Agdana, Nicole Ken)Document9 pagesANAPHY Lec Session #17 - SAS (Agdana, Nicole Ken)Nicole Ken AgdanaNo ratings yet

- DLL G 10 Q1 Week6Document3 pagesDLL G 10 Q1 Week6heideNo ratings yet

- Schedule of LoadsDocument2 pagesSchedule of LoadsNelsonPolinarLaurdenNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter - Science ActivitiesDocument4 pages2nd Quarter - Science ActivitiesHyeon Bin LeeNo ratings yet

- First Quarter Examination 2017-2018Document5 pagesFirst Quarter Examination 2017-2018Erwin RelucioNo ratings yet

- Induced Magnetism Cot2Document18 pagesInduced Magnetism Cot2Liezel fullantesNo ratings yet

- Moment of InertiaDocument5 pagesMoment of Inertiaanurag3069No ratings yet

- Me, Myself, and The Others: Development of Values, Principles and Ideologies, Love and Attraction, and Risk Taking Behavior and Peer InfluencesDocument9 pagesMe, Myself, and The Others: Development of Values, Principles and Ideologies, Love and Attraction, and Risk Taking Behavior and Peer InfluencesCla100% (1)

- RA 51 - HVAC Duct, Accessories and Equipment InstallationDocument6 pagesRA 51 - HVAC Duct, Accessories and Equipment InstallationzahidNo ratings yet

- Intro To MagnetismDocument28 pagesIntro To Magnetismmark gonzales100% (1)

- Composite Construction Group 3 4aDocument7 pagesComposite Construction Group 3 4aJem GarciaNo ratings yet

- Test Item Analysis: Elizabeth B. Beniasan Carlito F. LayosDocument5 pagesTest Item Analysis: Elizabeth B. Beniasan Carlito F. LayosLianne Kaye ApasaoNo ratings yet

- Design of A 1000 Ton Round Square and Flat Steel Bar UpdatedDocument77 pagesDesign of A 1000 Ton Round Square and Flat Steel Bar UpdatedReynalene PanaliganNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 UCSP Week 3Document5 pagesQuarter 2 UCSP Week 3John Allan GalvezNo ratings yet

- GRADE 8 - Earthquake and FaultsDocument64 pagesGRADE 8 - Earthquake and FaultsNELJAMES OBSIOMA DEL ROSARIONo ratings yet

- Q2 Week 1 UCSP DLLDocument3 pagesQ2 Week 1 UCSP DLLJay Kevin CalalangNo ratings yet

- What Do You Call It When You Drop A Lemon?: Alphabetize: Grade Three (Grade 3) Vocabulary List OneDocument31 pagesWhat Do You Call It When You Drop A Lemon?: Alphabetize: Grade Three (Grade 3) Vocabulary List Oneh_fazilNo ratings yet

- Mapúa University PDFDocument26 pagesMapúa University PDFRodolfo Rey TorresNo ratings yet

- FvkutxcguvDocument15 pagesFvkutxcguvAnonymous rVCtuDRNo ratings yet

- Torsion ProblemsDocument7 pagesTorsion ProblemsLouie G NavaltaNo ratings yet

- ResumeDocument4 pagesResumeAaRomalyn F. ValeraNo ratings yet

- IR Drug Test 1Document4 pagesIR Drug Test 1liaura carvalhoNo ratings yet

- Science Quiz BeeDocument4 pagesScience Quiz BeeLyno ReyNo ratings yet

- 09 Task PerformanceDocument5 pages09 Task PerformanceAngel Joy CalingasanNo ratings yet

- General Education ScienceDocument5 pagesGeneral Education ScienceLauro Jr. J Cantero100% (1)

- Earth and Life Science Mock TestDocument7 pagesEarth and Life Science Mock TestFederico Bautista Vacal Jr.No ratings yet

- Competency Profile Chart (CPC)Document21 pagesCompetency Profile Chart (CPC)nur balqis kamaruzamanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 12 - Position PaperDocument6 pagesLesson 12 - Position PaperArmand DalionNo ratings yet

- MAGNETDocument50 pagesMAGNETJason CookNo ratings yet

- ICT Syllabus Form 1 - 4Document46 pagesICT Syllabus Form 1 - 4ALI MWALIMU0% (1)

- Upang Parental Consent Rle Hospital DutyDocument3 pagesUpang Parental Consent Rle Hospital DutyFaith CalimlimNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing, Q2 Weeks4 6Document7 pagesCreative Writing, Q2 Weeks4 6AKnownKneeMouseeNo ratings yet

- World Religion Module 6 4Document13 pagesWorld Religion Module 6 4FrennyNo ratings yet

- Networks Tutorial: by Amritha Bhat (EDTECH 541)Document23 pagesNetworks Tutorial: by Amritha Bhat (EDTECH 541)amritharauNo ratings yet

- Post Test Sci 7Document7 pagesPost Test Sci 7Elsa Geagoni Abrasaldo100% (2)

- The Historical Architecture of KoreaDocument11 pagesThe Historical Architecture of KoreaMj JimenezNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Class Program For Blended LearningDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education: Class Program For Blended LearningKeyrenNo ratings yet

- Teacher'S Individual Plan For Professional DevelopmentDocument2 pagesTeacher'S Individual Plan For Professional Developmentmuhajirin b saliNo ratings yet

- St. Alexius College Integrated School DepartmentDocument7 pagesSt. Alexius College Integrated School DepartmentKrisTin Magbanua JocsonNo ratings yet

- FC - GenscienceDocument8 pagesFC - GenscienceReden OriolaNo ratings yet

- Computer Quiz 3 Grade 3 Practice Sheet.Document4 pagesComputer Quiz 3 Grade 3 Practice Sheet.ezzeldin3khaterNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 A - VDocument36 pagesUnit 1 A - VMugesh VairavanNo ratings yet

- ANAPHY Lec Session #16 - SAS (Agdana, Nicole Ken)Document10 pagesANAPHY Lec Session #16 - SAS (Agdana, Nicole Ken)Nicole Ken AgdanaNo ratings yet

- Bayanihan Concept PaperDocument4 pagesBayanihan Concept PaperDiane Hope Martinez50% (2)

- Chapter 1 GR.4Document10 pagesChapter 1 GR.4Allyssa OpantoNo ratings yet

- Research Fa1.2 - Arao, Ma - Andrea D.Document8 pagesResearch Fa1.2 - Arao, Ma - Andrea D.Iya AraoNo ratings yet

- The Evaluation of Temporary Earthquake Houses Dismantling Process in The Context of Building Waste ManagementDocument9 pagesThe Evaluation of Temporary Earthquake Houses Dismantling Process in The Context of Building Waste ManagementJohn Rameses BaroniaNo ratings yet

- Temporary Housing Respond To Disasters in Developing Countries Case Study Iran Ardabil and Lorestan Province EarthquakesDocument8 pagesTemporary Housing Respond To Disasters in Developing Countries Case Study Iran Ardabil and Lorestan Province EarthquakesJohn Rameses BaroniaNo ratings yet

- PM Poster Spring 2021Document2 pagesPM Poster Spring 2021John Rameses BaroniaNo ratings yet

- Olicy: Financing Postdisaster Reconstruction in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesOlicy: Financing Postdisaster Reconstruction in The PhilippinesJohn Rameses BaroniaNo ratings yet

- Research 1 and 2Document8 pagesResearch 1 and 2Jean TroncoNo ratings yet

- Appendix D1-FormDocument2 pagesAppendix D1-FormrodystjamesNo ratings yet

- Architectural Working Drawing II (Presentaion)Document27 pagesArchitectural Working Drawing II (Presentaion)Yohannes AlemayehuNo ratings yet

- Literature Review (M.S.Ansari)Document23 pagesLiterature Review (M.S.Ansari)Shreya SinghNo ratings yet

- Technical Bid Evaluation SampleDocument79 pagesTechnical Bid Evaluation SampleSaroj MahatoNo ratings yet

- BP 220Document193 pagesBP 220Dexter RabutinNo ratings yet

- Ryterna Garage Doors 2018 PDFDocument64 pagesRyterna Garage Doors 2018 PDFElmer HuamanNo ratings yet

- Lotus Temple - Literature StudyDocument13 pagesLotus Temple - Literature StudyHarshithaManjunath100% (9)

- Spectacle of Power - Hispanic Structuring of The Colonial SpaceDocument1 pageSpectacle of Power - Hispanic Structuring of The Colonial SpaceRose Ann VillameaNo ratings yet

- Straw Bale ConstructionDocument72 pagesStraw Bale ConstructionRodrigo Mindlin LoebNo ratings yet

- M Tower: JUNE 28th, 2022Document40 pagesM Tower: JUNE 28th, 2022the next miamiNo ratings yet

- 2019-08-25 Rated Boq - InteriorDocument2 pages2019-08-25 Rated Boq - Interiorstudiopy0% (1)

- PHD Thesis - Marios Stergiopoulos 6343047Document235 pagesPHD Thesis - Marios Stergiopoulos 6343047Dushan RomicNo ratings yet

- Governing Laws: PD 1096: National Building Code of The PhilippinesDocument1 pageGoverning Laws: PD 1096: National Building Code of The PhilippinesNeil AbellaNo ratings yet

- 2004 TS Bridge UZR UNR Final PDFDocument292 pages2004 TS Bridge UZR UNR Final PDFzakaria200811060No ratings yet

- CMPMDocument34 pagesCMPMLara RiveraNo ratings yet

- Hotel Design ProblemDocument4 pagesHotel Design ProblemRudresh AroraNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Make-Shift Hospitals: With Provision of Incremental ExpansionDocument7 pagesCovid-19 Make-Shift Hospitals: With Provision of Incremental ExpansionAjay ChourasiaNo ratings yet

- Drawing PDFDocument1 pageDrawing PDFimmeshNo ratings yet

- Summary of Bill A - Main Bill: 3107 Malta Tourism AuthorityDocument21 pagesSummary of Bill A - Main Bill: 3107 Malta Tourism AuthoritySaurabh TiwariNo ratings yet

- LEED Rated Green Buildings in 2006-2007Document6 pagesLEED Rated Green Buildings in 2006-2007A SinghNo ratings yet

- Speaking CardsDocument1 pageSpeaking CardsKaterina Yaroshko100% (1)

- Washrooms EstimateDocument93 pagesWashrooms EstimateAbu Bakar Muzamil ButtNo ratings yet

- Camus 5Document1 pageCamus 5shuckss taloNo ratings yet

- Diseño de ZapataDocument4 pagesDiseño de ZapataLuis Carlos SalasNo ratings yet