Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Short Story - The Necklace

Uploaded by

Titah Afandi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

469 views2 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

469 views2 pagesShort Story - The Necklace

Uploaded by

Titah AfandiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

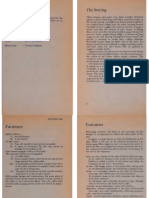

The Necklace

by Guy de Maupassant

She was one of those pretty and charming girls born, as

though fate had blundered over her, into a family of artisans. She let

herself be married off to a little clerk in the Ministry of Education. She

suffered from the poorness of her house, from its mean walls, worn

chairs and ugly curtains. She imagined silent antechambers, heavy

with Oriental tapestries, lit by torches in lofty bronze sockets, with two

tall footmen in knee-breeches sleeping in large armchairs, overcome

by the heavy warmth of the stove. She imagined vast saloons hung

with antique silks, exquisite pieces of furniture supporting priceless

ornaments, and small, charming, perfumed rooms, created just for little

parties of intimate friends, men who were famous and sought after,

whose homage roused every other woman's envious longings.

One evening, her husband came home with an exultant air, holding a large envelope in his hand. "Here's

something for you," he said.

Swiftly she tore the paper and drew out a printed card on which were these words "The Minister of Education

and Madame Ramponneau request the pleasure of the company of Monsieur and Madame Loisel at the Ministry on the

evening of Monday, January the 18th."

Instead of being delighted, as her husband hoped, she flung the invitation petulantly across the table, murmuring,

"What do you want me to do with this?" She looked at him out of furious eyes, and said impatiently, "And what do you

suppose I am to wear at such an affair?"

He was heartbroken. "Look Mathilde," he persisted, "what would be the cost of a suitable dress, which you could

use on other occasions as well, something very simple?"

She thought for several seconds. At last, she replied with some hesitation, "I don't know exactly, but I think I

could do it on four hundred francs."

He grew slightly pale, for this was exactly the amount he had been saving for a gun, intending to get a little

shooting next summer. Nevertheless he said, "Very well. I'll give you four hundred francs. But try and get a really nice

dress with the money."

The day of the party grew nearer and Madame Loisel seemed sad, uneasy and anxious. One evening her husband

said to her, "What's the matter with you?"

"I'm utterly miserable at not having any jewels, not a single stone, to wear," she replied. "I shall look at absolutely

no one. I would almost rather not go to the party."

"How stupid you are!" exclaimed her husband, "Go and see Madame Forestier and ask her to lend you some

jewels."

She uttered a cry of delight. "That's true. I never thought of it."

The day of the party arrived. Madame Loisel was a success. She was the prettiest woman present, elegant,

graceful, smiling, and quite above herself with happiness. The minister noticed her.

She left about four in the morning. At last they found on the quay one of those old night-prowling carriages which

were only to be seen in Paris after dark, as though they were ashamed of their shabbiness in the daylight. It brought them

to their door in the Rue des Martyrs, and sadly they walked up to their own apartment.

She took off the garment in which she had wrapped her shoulders, so as to see herself in all her glory before the

mirror. But suddenly she uttered a cry. The necklace was no longer round her neck. They searched in folds of her dress,

in folds of the coat, in the pockets, everywhere. They could not find it.

In a shop at the Palais-Royal, they found a string of diamonds which seemed to them exactly like the one they

were looking for. It was worth forty thousand francs. They were allowed to have it for thirty-six thousand. Loisel possessed

eighteen thousand francs left to him by his father. He intended to borrow the rest.

Madame Loisel came to know the ghastly life of abject poverty. She came to know the heavy work of the house,

the hateful duties of the kitchen. Her husband worked in the evenings at putting straight a merchant's accounts, and often

at night he did copying at two pence-half penny a page. Madame Loisel looked old now. Her hair was badly done, her

skirts were awry, her hands were red.

One Sunday, as she had gone for a walk along the Champs-Elysees to freshen herself after the labours of the

week, she caught sight suddenly of a woman who was taking a child out for a walk. It was Madame Forestier. She did not

recognise Mathilde until she told her friend. She uttered a cry, "Oh! My poor Mathilde, how you have changed!"

"Yes, I've had some hard times since I saw you last; and many sorrows ... and all on your account. You remember

the diamond necklace you lent me for the ball at the Ministry? Well, I lost it. I brought you another one just like it. And

for the last ten years we have been paying for it."

Madame Forestier had halted. "You say you bought a diamond necklace to replace mine?" Madame Forestier,

deeply moved, took her two hands, "Oh, my poor Mathilde! But mine was an imitation. It was worth at the very most five

hundred francs!"

You might also like

- Virgo: The Complete Book ofDocument48 pagesVirgo: The Complete Book ofadityaacharya44No ratings yet

- American ApparelDocument40 pagesAmerican Apparellaurent.pouchoy5472No ratings yet

- Spanish and Moorish FashionsDocument52 pagesSpanish and Moorish FashionsNuit Pritsana100% (16)

- An ESL Lessonplan On Fast Fashion. C1 Lesson Plan. Student Version.Document2 pagesAn ESL Lessonplan On Fast Fashion. C1 Lesson Plan. Student Version.EDANEE ShopNo ratings yet

- EN MELCsDocument7 pagesEN MELCsNiña Anne DelaCruz RamosNo ratings yet

- Toefl Itp - Listening ComprehensionDocument6 pagesToefl Itp - Listening ComprehensionTitah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Kernel Sentence LPDocument2 pagesKernel Sentence LPGelli AbabaoNo ratings yet

- PIVOT 4A LESSON EXEMPLARS USING THE IDEA INSTRUCTIONAL PROCESSDocument10 pagesPIVOT 4A LESSON EXEMPLARS USING THE IDEA INSTRUCTIONAL PROCESSJanice GaboteroNo ratings yet

- Week 6-Quarter 4 - Discover Literature As A Tool To Assert One's Unique Identity and To Better Understand Other PeopleDocument3 pagesWeek 6-Quarter 4 - Discover Literature As A Tool To Assert One's Unique Identity and To Better Understand Other PeopleAcel Manalo CastilloNo ratings yet

- DLL - 4th QRTR - Week 7Document6 pagesDLL - 4th QRTR - Week 7AyreKeeshiaGwinHiponiaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Words Phrases ConversationsDocument44 pagesChinese Words Phrases ConversationsAjaz BannaNo ratings yet

- FBS QTR 1 Las 5Document6 pagesFBS QTR 1 Las 5Daphne Del Rosario100% (1)

- Stella McCartneyDocument17 pagesStella McCartneyAriel ThiNo ratings yet

- Rolex Watches - ManualDocument27 pagesRolex Watches - ManualDebbie Carter0% (1)

- Lesson Plan ModalsDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Modalsfaith clavaton100% (1)

- Diagnostic Post-Test TOEFL ITP - Taken From Longman TOEFLDocument24 pagesDiagnostic Post-Test TOEFL ITP - Taken From Longman TOEFLTitah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Intended Learning Outcomes: India-Land of PrayerDocument24 pagesIntended Learning Outcomes: India-Land of PrayerJewo CanterasNo ratings yet

- Topic: How A Selection May Be Influenced by Culture, History, Environment and Other FactorsDocument6 pagesTopic: How A Selection May Be Influenced by Culture, History, Environment and Other FactorsAleli Dueñas Antigo MarianoNo ratings yet

- Figures of Speech Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesFigures of Speech Lesson PlanMarylin Tarongoy100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Literary Conflicts q4 m5Document6 pagesLesson Plan Literary Conflicts q4 m5Maryknoll PonceNo ratings yet

- The Little Prince (Detailed Lesson Plan) Grade 10Document32 pagesThe Little Prince (Detailed Lesson Plan) Grade 10Joseph Edwin AglionesNo ratings yet

- Types of SourcesDocument11 pagesTypes of SourcesJose GerogalemNo ratings yet

- En9Lc-Ivh-2.15: Evaluating BooksDocument3 pagesEn9Lc-Ivh-2.15: Evaluating BooksNIMFA SEPARANo ratings yet

- Module Week 1Document8 pagesModule Week 1Kyzil Praise IsmaelNo ratings yet

- Tuazon Lesson Exemplar Grammatical Signals or Expressions English 8Document9 pagesTuazon Lesson Exemplar Grammatical Signals or Expressions English 8Leigh Bao-iranNo ratings yet

- Rem Ins LPDocument7 pagesRem Ins LPNikko Franco TemplonuevoNo ratings yet

- Plient Likea A BambooDocument13 pagesPlient Likea A BambooLucile LlevaNo ratings yet

- Week 2Document4 pagesWeek 2april deeNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan: Sibalom National High School 7 Anna Jane A. Mendoza English FourthDocument7 pagesDaily Lesson Plan: Sibalom National High School 7 Anna Jane A. Mendoza English Fourthanon_732395672No ratings yet

- 1 Module 1 Lesson 1 Initial TasksDocument8 pages1 Module 1 Lesson 1 Initial TasksJennefer Gudao AranillaNo ratings yet

- Remedial vocabulary instruction techniquesDocument2 pagesRemedial vocabulary instruction techniquesLadyNareth MierdoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 1Document9 pagesLesson Plan 1Rizza Mae SamillanoNo ratings yet

- Activity 6 - ELED 12 (DOLOR)Document5 pagesActivity 6 - ELED 12 (DOLOR)Jade DolorNo ratings yet

- 3rd QUARTER LSAR ENGLISH 10Document5 pages3rd QUARTER LSAR ENGLISH 10Jemar Quezon LifanaNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Literature Lesson PlanDocument16 pagesIndonesian Literature Lesson PlanFirda'sa Nurvika NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in English 9Document4 pagesLesson Plan in English 9Ka Lok LeeNo ratings yet

- Mapping the Development of Philippine LiteratureDocument25 pagesMapping the Development of Philippine LiteraturePatricia FelicianoNo ratings yet

- The Stranger Focusing On Conflicts - PPTX Lesson 5Document65 pagesThe Stranger Focusing On Conflicts - PPTX Lesson 5DenielNo ratings yet

- The Telephone LPDocument9 pagesThe Telephone LPNicca Dennise TesadoNo ratings yet

- Like The Molave, English Power Point PresentationDocument24 pagesLike The Molave, English Power Point PresentationIvan Melvin Alemaida100% (2)

- GRADE 9 Matrix-for-the-Learning-Continuity-PlanDocument8 pagesGRADE 9 Matrix-for-the-Learning-Continuity-PlanMarliel P. CastillejosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document18 pagesLesson 2Emon MijasNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesDetailed Lesson PlanJerwin LualhatiNo ratings yet

- English 8-8Document7 pagesEnglish 8-8Kynneza UniqueNo ratings yet

- Edited Footnote To Youth DLPDocument11 pagesEdited Footnote To Youth DLPJan Myka BabasNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 DLP Lesson 2Document7 pagesGrade 8 DLP Lesson 2Vanessa R. AbadNo ratings yet

- Grade 08 Module Quarter 2Document55 pagesGrade 08 Module Quarter 2Skyler AzureNo ratings yet

- SUMMATIVEDocument3 pagesSUMMATIVEmekale malayoNo ratings yet

- Unfinished Determine the Worth of Ideas Mentioned in the Text Listened To (1)Document14 pagesUnfinished Determine the Worth of Ideas Mentioned in the Text Listened To (1)christianjaypitloNo ratings yet

- 11 INFLUENCE OF CULTURE ETC Lesson PlanDocument9 pages11 INFLUENCE OF CULTURE ETC Lesson PlanJodelyn Mae Singco CangrejoNo ratings yet

- Prefinals Lesson3 Fun - PoetryDocument17 pagesPrefinals Lesson3 Fun - PoetryCarina Margallo CelajeNo ratings yet

- Quarter 1-Week 6 - Day 4.revisedDocument5 pagesQuarter 1-Week 6 - Day 4.revisedJigz FamulaganNo ratings yet

- LP 3 (Nibelungenlied)Document3 pagesLP 3 (Nibelungenlied)JonalynNo ratings yet

- MODULE 3 and 4: "The Anglo-Saxon To The Seventh Century"Document10 pagesMODULE 3 and 4: "The Anglo-Saxon To The Seventh Century"Elaine Mhanlimux AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- 7th Grade English Lesson on Philippine LiteratureDocument2 pages7th Grade English Lesson on Philippine LiteratureRochelle Anne Domingo100% (1)

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7 Cot1 MelcsDocument3 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7 Cot1 MelcsMiriam Ebora GatdulaNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesLesson PlanRose YulasNo ratings yet

- MECHANICS and PROCESS OF SPEAKINGDocument8 pagesMECHANICS and PROCESS OF SPEAKINGongcojessamarie0No ratings yet

- LESSON EXEMPLAR - Basic Factors of DeliveryDocument7 pagesLESSON EXEMPLAR - Basic Factors of DeliveryJade JayawonNo ratings yet

- Assert Identity Through Filipino LiteratureDocument11 pagesAssert Identity Through Filipino LiteratureJenipe CodiumNo ratings yet

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Teaching English 10Document3 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Teaching English 10Raquel LimboNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan (DLP in English)Document9 pagesDaily Lesson Plan (DLP in English)Alwin AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7Document9 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in English 7Araceli MersulaNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheets 1st Quarter Grade 7Document4 pagesActivity Sheets 1st Quarter Grade 7Pau Jane Ortega ConsulNo ratings yet

- Auld Lang SyneDocument2 pagesAuld Lang SyneMartha Andrea PatcoNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Wilfrido Nolledo's Short Story "Rice WineDocument23 pagesAnalysis of Wilfrido Nolledo's Short Story "Rice WineKat-kat GrandeNo ratings yet

- The Necklace: Guy de MaupassantDocument11 pagesThe Necklace: Guy de MaupassantClarisse DomagtoyNo ratings yet

- The Necklace: Guy de MaupassantDocument11 pagesThe Necklace: Guy de MaupassantBlair BassNo ratings yet

- The Necklace (1) - CompressedDocument12 pagesThe Necklace (1) - CompressedAgus MarzukiNo ratings yet

- The Necklace Text OUxBElQv2nDocument8 pagesThe Necklace Text OUxBElQv2nanuragsamanta1208No ratings yet

- TOEFL ITP - LISTENING COMPREHENSION Part 3Document6 pagesTOEFL ITP - LISTENING COMPREHENSION Part 3Titah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Media Pembelajaran Kelas Ix KD 3.7 - 4.7Document7 pagesMedia Pembelajaran Kelas Ix KD 3.7 - 4.7Titah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Assignment IDocument2 pagesAssignment ITitah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Peer AssessmentDocument1 pagePeer AssessmentTitah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Video TranscriptDocument1 pageVideo TranscriptTitah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 (Expressing Intention)Document8 pagesChapter 3 (Expressing Intention)Titah AfandiNo ratings yet

- English Curriculum: F T T F F F T F F T F T F FDocument1 pageEnglish Curriculum: F T T F F F T F F T F T F FTitah AfandiNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Muzammil: NameDocument8 pagesMuhammad Muzammil: NameRai Javed Iqbal KharalNo ratings yet

- Early European dolls manufacturing history and evolution outlinedDocument4 pagesEarly European dolls manufacturing history and evolution outlinedRomina AnhaltNo ratings yet

- Presentation On KiwiDocument16 pagesPresentation On Kiwicleanliness50% (4)

- Group 1: Alvarez, Banzuela, Baraero, VillegasDocument15 pagesGroup 1: Alvarez, Banzuela, Baraero, VillegasNica HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Third Quarter Supplemental Activities: Scoring Rubrics For Photo CollageDocument8 pagesThird Quarter Supplemental Activities: Scoring Rubrics For Photo Collagejilleanne quianNo ratings yet

- Azim Uddin Chowdhury-Production System of R.S. Sweater (PVT.) LTD (1) .Docx Final FileDocument35 pagesAzim Uddin Chowdhury-Production System of R.S. Sweater (PVT.) LTD (1) .Docx Final FileSakera BegumNo ratings yet

- Company Review On Aditya Birla GroupDocument19 pagesCompany Review On Aditya Birla GroupSharan ChristinaNo ratings yet

- Man With The Twisted LipDocument13 pagesMan With The Twisted LipTim BonineNo ratings yet

- Seating Arrangement Questions and AnswersDocument7 pagesSeating Arrangement Questions and AnswersMuralidharan RamamurthyNo ratings yet

- Feasibility On ShirtsDocument33 pagesFeasibility On ShirtsAna Imbuido BaldonNo ratings yet

- Architecture in The Modern Era: "Form Follows Function"Document3 pagesArchitecture in The Modern Era: "Form Follows Function"Hashi ObobNo ratings yet

- Conversation Questions - DocxclothesDocument4 pagesConversation Questions - DocxclothesШабохина АннаNo ratings yet

- My Brand XO Nine ClothingDocument6 pagesMy Brand XO Nine Clothingzeronine2325No ratings yet

- CH Florence Follow Up 10.5.2021 - RedactedDocument10 pagesCH Florence Follow Up 10.5.2021 - RedactedABC15 NewsNo ratings yet

- Communicating Across Cultures: A Study of Intercultural Communication Practices in India, Switzerland and JapanDocument7 pagesCommunicating Across Cultures: A Study of Intercultural Communication Practices in India, Switzerland and JapanAustine Crucillo TangNo ratings yet

- Yoruba Lang2 Js2 Third TermDocument20 pagesYoruba Lang2 Js2 Third Termpalmer okiemuteNo ratings yet

- Villa MareaDocument5 pagesVilla MareaZain IhsanNo ratings yet

- CF StandardsDocument4 pagesCF StandardsIslamic SolutionNo ratings yet

- The Tailor's Guiding HandDocument14 pagesThe Tailor's Guiding HandLirwanNo ratings yet

- 09PersonalProtectiveEquipment IOGP577version1.2Document2 pages09PersonalProtectiveEquipment IOGP577version1.2Ismail SultanNo ratings yet

- Old Story TimeDocument43 pagesOld Story TimeShanné GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Diversity in Families 9th Edition Maxine Baca ZinnDocument38 pagesTest Bank For Diversity in Families 9th Edition Maxine Baca Zinnernestocolonx88p100% (9)