Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Senecafallsselmastonewall

Senecafallsselmastonewall

Uploaded by

api-6452316620 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

74 views12 pagesOriginal Title

senecafallsselmastonewall

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

74 views12 pagesSenecafallsselmastonewall

Senecafallsselmastonewall

Uploaded by

api-645231662Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

‘Taerese QUINN AND Enrca R. MEINERS

{yr name order reflects a publishing rotation snd not an authorship hierarchy; this isa

gi viten article,

P Weica R. Meiners teaches and organizes in Chicago. She has written about her ongoing.

ator and learning in anti-militariation eampigns, edvestional justice struggles, prison

ition and reform movements, and queer aud imnigrant rights organizing in Flaunt

it! Queers Organizing for Public Education and Juatioe 2009, eter Lang), Right to

Be Hostile: Schools, Prisons, and the Making of Public Enemies (2007), and

adical Teacher, Merdians, ARBA Chicago, and Soiad Justice.

“Therese Quinnis an seco profisor of a try and tector ofthe Moseam and

ion Stes Program athe Univeriyof linet Ching, Sh va bundng :

S member of Chicagoland Resrachers end Advocates or Tansformaive Eaton, |

(Ces eatehagn org). Her mot recent books ce ton Soil ute |

| fdwation:Cultarees Commons (2012), Servalitesin Eduction: Render (2012) nd

ih same sex manage eg ans wor Lave Coe om |

the television series Orange 1s the New Black on the cover of

Time magazine, lots of queer sexon Game of Thrones, and

President Obama's invocation of the Stonewall rebellion in

is 2013 Inaugural Address” gay people have in fll fabulous fashion, cleasly

‘rived, With manage certificates in our tuxedo pockets, our military

3 ustige movement—have let behind our worst problems and soared past the

FE Sirish line toequalty and rights. Right?

‘This view of social progress strikes a familiar chord for many of us working

inschools, where the difficulties ofthe past are often explained as vastly distant,

ust folktales from an incomprehensible time, place, and people, Slavery?

‘Women coulda’ vote or own property? Gay people arrested, fired, castrated?

Who would do that? Notus, that’s for sure, Who were those people?

"The ideas that we are different from they, and that now is better than then,

form a kind of comfortable common sense; the feeling that things are getting

better ean be a relief when we are confronted with history's horrors. For that

| Tetoon, isnot surprising that progress narratives, often pained with a focus

‘on changing individual behavior by promoting respect for difference, faleness,

nd tolerance, ave dominant in so many diversity and multicultural cuticulurm

_ frameworks. Ongoing examples of systemie violations of human dignity and

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 27

safety are often ignored and even banned from discussion in public education a

settings. 1&5 easier and, let's face it, more profitable, to tout the right to gey nee

‘marriage than the epidemie plight af homeless gay and trans youth. After the : j

2014 killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black youth in Ferguson, Missouri, eae

by awhite police offices, the superintendent ofa school district in Iino aa

banned discussion ofthe shooting and related protests, “Teachers have been told bein

not to diseuss [the shooting] and if students bring it up, they should change the ey

subject "The implied message: What's tervibleis past; everything is bettr nom,

‘What int better can be ateibuted toa few bad people, not bad socal structures

and oppressive policies. And, finally, what int better its OK to ignore; infact,

silence might be mandatory.

Progress narratives support dangerously ahistoric understandings of social

change, narrowing our attention. For example, why does everyone study the :

Civil Rights Movernent but not the eriminal justice system? a

Progress narratives aleost always focus on individuals in ways that folate ete

them from their historical context and erase the importance of collective effots. ie

Every individualizing hero story-osa Parks wouldn't move tothe back ofthe ra

dbus, and just like thet, everything changed—obseures the labor ofthe many can

others who dreamed up and tried out similar tacts eatlier and those who

turned a precipitating event into @ movement. Trained as an organizer a the

Highlander Folk School, Resa Parks was an active member of racial justice ce

“organizations long before and long after the Montgomery bus boycott, Keeping ee

organizations and other people in the story doesn't diminish Parks; rather, it ee

puts her action into a context—the aetual planning and hard work that it takes peop

to achieve justice. 3

‘Not surprisingly, just as curriculum on racial justice often centers on

vidual struggle in the pest and the need to be indivially “nee” now, most

schools! approaches to LGBTQ issues (when not silenced completely) also

admonish us to plant flag for dauntless progress. But what’ the reality?

every

‘Standing on Their Shoulders

‘When Obama’ inaugural speech linked Seneca Falls, Selma and 7

Stonevall—important milestones in the struggle for gene ecal, and In

sexual equality—he reminded us how much things have, i fact, changed, The

1848 Women’ Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, was ertcal i

‘the movement for (white) women’ enfranchisement, and the "Declaration x

of Sontimonts” presented and endorsed at the gathering is tila powerful antich

aurtcalation of what the writers’ described as mens “absolute tyranny” over ident

‘women. Patriarchy lingers on, but we ate at some distance from absolute ‘wiki

‘tyranny today. arepl

1 1963, atthe conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March, Marta pet

Lather King Je deseribed the impact of racial apartheid he used the term pe

“segregated society", repeatedly emindinghis audience: We've come along fores

‘way... Weare not about to turn around. ... Weare on the move." The next

RETHINKING SEXISM, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY

‘year, Stokely Carmichael called for Black Power and the Black Panthers were

formed in Oakland, California

‘Also in 1966, transgendered women and gay “hustlers” at the Compton.

(Cafeteria in San Francisco resisted when police attempted to arrest them for

congregating in the restaurant-—one of the first examples of queer resistance to

Ieing eximinalized. Then, in 1969, during a brutal raid of the Stonewall ian, a

_gay bar in New York's Greenwich Village, LGBTQ people fought back:

‘Led by people deseribed by many as drag queens and batch lesbisns,

bar patrons, joined by street people, began yelling “Gay Power!”

and throwing shoes, coins, and bricks atthe officers. Over the next

several nights, police and queers clashed repeatedly in the streets of

the West Villages

‘Stonewall is now often rlerred to a the beginning ofthe present-day

‘LOBTOrights moverentin the United Stats. In our view it was a moment

red by and builton many others, including the movement agninst

‘the war in Vietnam; Compton; the bith of the Black Power Movement and

"> the Black Panthers; the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican Hibesation organization;

CChicana/o and women’ iberstion organizing; and marches and protests

erywhere, Fach ofthese eruptions, assertions, and eoaleseings sent similar

‘messages about the importance of mobilization to demand transformations of

“the status quo. Stonewall was immediately, locally, an uprising against police

‘utality and, broadly, one wave among many against oppression and for social

ange. The whole worl wes erupting wth demands for justice and LGBTQ

“people were organizing, too. And westil are,

= ut nowy given the broad soil vision that ingpired those movements, we

se to question our current strategies and goals Sue, some of us have come

ne distance, but where do we want to end up? In partiula, the visible surge

support for selected lesbian and gay ives-often those who are white and

_ pel rosoureed, want to mars, have children or join the military, are “people

=a ith? and so on-~places pressure on those of us working for quee justice in

hoo! and other contexts to critically revaluste our organizing, Tb that end, we

ee thre itertelated questo

“What are the aims of our work liberation or assimilation?

_ With whomare we in coalition, community, and conversation?

“An our labors for just schools and communities, how can we ensure that we

-And, for those new to this area, we use queer

Hfile—as an adjective and as a noum that refers to all sexualities and gender

ties that are outside and challenging of normative, binary categories.

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

RETHINKING SEXISM, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY

Of course, not all queers are white or able-bodied or wealthy, so LGBTQ,

liberation necessarily includes struggles against racism, ableism, and capitalism,

‘These forms of domination are inseparable. The Q, therefor, signifies a

political stance that our struggles for freedom and self-determination are one.

As poet and activist Audre Torde noted in 1982: “There is no such thing as a

single-issue struggle, because we do not live singl-issue lives”

From Equality to Liberation

‘As we said earlier, the increased logitimacy and limited success of LGBT.

rights-based movements in the United States motivate us to step back and

ically assess LGBTQ and other socal justice organizing. What are our goals?

Eequality—-full participation in the status quo—or liberation and collective

transformation? Over the lst 20 years, the focus of mainstream lesbian and

‘gay organizations in the United States, while never monolithic, has been

assimilation, characterized by a prioritization of issues such as full and equal

participation in the military and marriage,

It’s easier and, let’s face it, more

profitable, to tout the right to gay

marriage than the epidemic plight of

homeless gay and trans youth.

‘This wasn't always the case. Many cerfior LGBTQ organizers drew on

international perspectives and movements. Henty Gerber, who founded

the nation’ first LGBTQ group, the Society for Human Rights, in 1924, was

inepired by the efforis of German activists. Gay and feminist liberationists in

the 1960s and "70s were often internationalist in their polities, linking their own

freedom to the liberation of nations and peoples globally, and identifying with

anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements everywhere? And, as policing and

punishment were central to queer lives, early LGBTQ liberation movements

analyzed the prison system, offered legal services, and created pen-pal programs

\ith people inside. They saw anti-prison organizing as central because LGBTQ.

lives and communities were criminalized. Being gay or lesbian was against the

Jaw and, therefore, supporting LGBT lives required not only prisoner support

‘work but also fighting agsinst police harassment, Many ofthe gay publications

of that period, including Lesbian Tide, off our Backs, and Gay Community

‘Neds, included letters and articles by people in prison and supported anti

prison organizing, The cover of the 1972 issue of Gay Sunshine: A Newspaper

of Gay Liberation featured a collage titled “We Are All Fagitives" that visually

connected queer struggles with anti-prison, anti-colonial, feminist, Black

Power, and othe

forefront of the

"70s.

Now, togeth

including the A

Against Violene

mainstream LG

ita hostof bene

receive any stat

markers ofour¢

affordable healt

contingent and

public housing 4

parental leave b

“The

issue

live s

Lord

Were also eo

suesessful eamps

course we're not

the permanent v

vehicles, initiate

of State Hillary ¢

‘Yemen, and othe

mts of thes:

riitarism and a

‘Thenatrowe

orgenizations—i

aceeptance ofan

should not be on

Building Goal

‘The trade-of

apparent than in

that lead to effec

the context: the:|

Dublic education

‘Power, and other liberation movements. Lesbian and gay organizers were at the

"forefront of the anti-war, civil rights, and feminist movements ofthe 1960s and

"10s.

‘Now, together with grassroots justice organizations across the United States,

including the Audre Lorde Projeet in New York and Communities United.

“Against Violence in San Franciseo, we question the current focus of most

‘mainstream LGBTQ organizations. For example, although marriage brings with

it ahost of benefits, this access is offered at a moment when fewer individuals

‘any state support or protection, Readers, we are sure, ean name the

markers of our crumbling publie sphere: ongoing struggles to access quality and

affordable healtheare; the decimation of unions and concurrent explosion of

contingent and ‘justin time” workers without any benefits; the eradication of

_ public housing and decimation of rent control; and the dearth of cildeave and

parental leave benefits,

“There is no such thing as a single-

issue struggle, because we do not

live single-issue lives.” —Audre

Lorde

We're also concerned sbout the politcal and practical implications of the

Secs campaign to gve LGBT people equltyin the US, military. OF

quality bt promoting lesbian and gay participation

© he permanent war economy is prablematie, Drone strikes by drivetless aerial

(on, have killed thousands, including children, in Pekistan,

2n, and other parts of the world, in attacks described as a “mass torture” of

esidents ofthese countries. Queer justice movements, we argue, must reject

ltacism and all forms of violent domination,

__The narrow aim of equality pursued by mainstzeam lesbian and gay

brganizations—including access to marriage andl the military—signifies

{ceptance of an unequal and unjust world, Assimilation into this status quo

houla not be our goal.

ent than in schools today. We can't begin the meaningful conversations

Hist lead to effective coalitions and strong comrmunities without understanding

context: the abandonment of any form of wealth redistribution for K-12

lic education, frontal assaults on teacher unions, bipartisan support for the

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

i

3

g

RETHINKING SEXISM, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY

privatization of schools through charters and vouchers, and the school-to-prison

pipeline, with its high suspension end expulsion rates for Black and Latina/o

students,

Our Chicago context offers an on-the-ground example of the effects of the

national trends toward expanding school privatization: The number of charter

‘schools doubled in the city between 2005 and 2012. The overwhelming majority

of teachers at charter schools locally and nationally are not unionized; in

‘Chicago these teachers are prevented by law from joining the Chicago Teachers

Union.

A nonunion workforve is flexible—without the right to due process that

contracts and tenure guarantee—and cheaper. In Chicago, the teachers laid

off, predominantly older and Aftican American, were replaced by newer, and

‘whites, teachers, often with little connection tothe schools and surrounding.

ity. A nonunion workforce also has less ability to push back against

‘regressive policies and to support students,

As schools are increasingly sites of temporary and precarious, unprotected

labor; this reshapes how teachers and other adults are likely to advoeate for

‘queer youth and take potentially unpopular positions, Our own research and

0

A MINUTE OF Tis,

IT'S THE

REVOLUTION

~ Slee Fanea

experience indicat

the national trend

and Mississippi, ms

school conditions —

students, Students

that foster speech, i

privatization and m

agenda of safe-scho

An agenda for q

Aemocratic and well

are invested in call

safer spaces for LGD

struggles. More bros

concern. The work f

Ttis the push for jus

supremacy, itis the v

anyone bebind, iis

of these intertwined

Justice, and are core

LGBT@—and al!—st

Students, teacher

need to work togethe

working conditions

supportive environ

‘queer curricular poss

Leave No One Behin

LGBTQ ediucatior

participate in, and de

serious problem why

anti-bullying laws tha

school-to-prison pipel

the risk of both being

struggles, and of too

community.

In fact, anti-bullys

tolaw enforcement a

of schoo! push-out.” I

Punishing polices ané

create profoundly uns

disabled youth, espect

| esprienceindzate that where school personnel work a wl students often

Gf themselves withot“ou” LGBTQ teachers and staf andwienr an

Allies. This reduces the number ‘of advocates for queer youth and. facilitators

{for Gay-Straight Alliances and similar student, ‘organizations. More broadly,

nation! trend toward vight o werk" ava sch asin chigens dior

__ th4 Missi) makes idea or workers to cxganize and toca ootenpat

ssthool conditions—fom ravst discipline practices to vk

students. Students benefit when schoo! employees have workplace protections

qe that foster speech, independent thinking, and advocacy, Pushing back on school

[Eyratuation and making alinces with teacher unfons has not bees nari

agenda of safe-school: ‘Movements, and it must be.

‘Ao agen for quer iberaon and tansfemation tana int blog

Aouishing corm

se lnvestd in chellenging ailinjstics For those of us tying to maleate

[sale spnces fo LGBTQ youth ur works absolutely iaepmreble hone

Struggles. More broadly, the goal of making schools ‘strong is a community

once. The work (or Ban just shone snot juan LODO strale

1Bisthe push for just and quality funding, itis the movement tose one

{9prenay tthe work or meaning immigration reir tet does ot eave

[severe behind itis the campaign tend sexual harassment ond ance a

: lertwined movements shape LGBTQ lives, ae cea ty edcanon

‘ ing schools as pen and aiming spare for

© LGBTQ—and all ‘students, staff, and communities.

Students, teaches union, grassroots community organizer: We all

‘o ensure that school ate worksites with good end fir

a. auctor, ike students and communities need secre and

Supportive environments o mos efetvly help create pact for ada ad

_sicer coniular possibilities, and tobe visbleand out LOBTO vole mata

}-GBTQ education justice movements are being ofiilly invited to

p Participate in, and de facto legitimate, the “new normal” in education, Theres

eros problem whon “gy enuaiy” means anetworkof song end pra

bullying laws that ed into zero tolerance disgline polices aad ne

en. tn this context, LGBTQ schoo sey organizing rans

He Fk ofboth being isolated from and not in dialogue with intesclted tag

and of oo nny defining who eounts asa member othe LoBro

[as ans baying programs thst rely on eiminaliation and lose ea

Slaw enforcement and ‘Punishment increase racialized and ‘homaphobie forms

fetoopush-ou In efforts o mak leaning sae or LGBT sedenie

ishing policies and closer Partnerships with the juvenile justice: system:

Profound unsafe schools for many young people Ast one empl,

bled youth, especially those who are Black and Brown, experience more and

GHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

barker dslin thn ots in seon* see

“rater od gender nonconfoning indaa fice some of heost panne

I vitriolic backlash and pimishment on our streets and in our classrooms, and communist-to

this is particularly 60 for those who are nonwhite and/or poor. Standing up for ‘Movement—h

uaseersghs dignisad otysefn one then tan ag ee

fortes sn gy youth, For exam Outshr tthe baron pati en

: ‘School Board in Winois backtracked on a policy they had just five days earlier ‘many civil righ

uneninouty sported tres geal peconoel opee be toga

tropa en genes nononfoning start Ding ders te Usttwer

sho dit vended te poly fa Noveber 2015 afghans cn ssa gt

I ‘that the Orono school *t was not in violation of Maine's Human Rights Act ‘the Gay Liberat

wien tbc th grade wangeniee staat a coing oho Pero whch

batrom ose temper

Onthe postive sin Dcembn 2012 fer packed sco meting ott ong

th Orange Cont Shoal odin Herida pteone fo ec, rola the on

td wanagender stents an aff dts sondern poleg poverty ana

i However, these battles are hard fought. Fear of moving “too fr, too fast” can repression,

| rsultinmorenens emake nd commutes doping te oo hen esta

i the work gets tough. At the forefront of the Stonewall uprising were transgender Rich’s life of res:

and gonder nonconforming people of color, angry and tired of systemic state

i ‘and police repression. As we work to support LGBTQ youth in schools, let's not

exemplified by

accept the 1974

1 forget the Tand Q. Award as an ind

‘Leaving no one behind demands that we analyze and critique what the state claiming the aw

and the schools identify as LGBTQ educational justice issues—Why not schoo} allwomen and s

her other feree,

and activist non

Walkerand Aud

policing and school privatization? It also demands that we ensure that the

strategies engaged build community and don’t harm or isolate others.

Lorde’ povesti

Rising Up! Infused through

== and Walker’ org

Seneca Falls, Selina, Stonewall—these were movements that pushed back, activism has con

arguing thatthe ‘same ol” plitis of patriarchy, white supreme, trans- and decades, fom th

‘homophobia that structure our everyday lives and institutions, fromm schools ‘women's mover

‘o courtrooms, must be disinantled. As the transgender sex workers and

‘queer bar patrons at Stonewall who fought back against police brutality and

‘marched against forms of state repression demonstrated, queer movements

have grounded histories demanding structural and systemic change forall. To

continue their work is to not settle for the status quo or the erumbs ofleted. We

need to put“our queer shoulders to the wheel’ to quote Allen Ginsberg, exercise

‘our radical imaginations, and work together to build the world we need.

hereurent supp

festment, and

against the oceay

All of these peop!

of persistence, of

there are nosing!

the long haul, am

‘What ean this look like in schools? The possibilities are endless Schools As these histo

should all be beautiful and resource-rich spaces filled with art, light, and well- ‘work extends toi

rested and supported teachers. Their students and staffs should be encouraged strategies, We are

tospeak and act. teachers, from Le

An important piece of transforming schools lies inthe eurriculum— pushing back aga

remembering, surfacing, and teaching radical queer history. And always, as we “These folks are n¢

RETHINKING SEXISM, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY

{mentioned atthe beginning, situating individuals inthe broader context of the

‘movements in which they worked, Bayard Rustin, for example, was a queer,

communist-to-socialist pacifist strategist who was ciel tothe Gv Righis

-Movement—he was central organize of the 1963 March om Washington for

Jobs and Freedom—yet his contributions were purposely obscured beeawse of his

pallteal views and homosexuality, and he was marginalized by

Finny cr ight leaders. Flay ly sed cle he ena

through labor organizing and inthe Commonist Patty

{USA to co-found the Mattachine Society the fst,

sustained gay onganlzation in the United Stats,

‘Faeries, which continues today. Sylvia Rivera, a

| ansgender Latina sex worker, was a member

‘ofthe Young Lords and played a central

sole inthe Stonewall uprising; she spoke

powerfully and organized against police

= repression,

Poet and activist Adrienne

‘ich’ life of resistance wes

‘exemplified by her refusal to

accep the 1974 National Book

‘Award asan individual, instead

claiming the award on behalf of

all yomen and sharing it with

her other fierce, queer artist

and activist nominees: Alice

_ Walker and Auer Lorde.

| Lorde’ powerful ideas are

‘infused throughout this essay,

and Walker’ organizing and

activism has continued across

‘women’s movernents of the 1960s to

‘her current support forthe Boyeott,

| Allofthese people remind us ofthe importance

ofppersistence, ofthe power of community, and that

_ there re no single-issue struggles, They were all in it for

‘helong haul, and not interested in assimilation.

[_Asthese histories hirstories* and herstories ground us, our

JF work extends to inelude unfolding and yet-to-be-imagined tacties and

Strategies, We are particularly energized by networks of youth, parents, ad

teachers, from Los Angeles to Atlanta, who are organizing, speaking out, and

Dushing back against punishing and undemocratic schools and communities

hese folks are not settling for business as usual in our public schools, nor are they

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

pithng teachers and labor struggles against the needs of Black and Brown parents.

‘The conditions that necessitate these labors and the work itself seem daunting,

but many ofthese groups—including Now York’s Audre Lorde Project, which

‘works to make communities safer and stronger for LGBTQ youth of eolor—offer

friendship and support slong, with radical visions that challenge the “new normal”

and foster social justice everywhere.

‘These powerful examples of the many who are struggling for transformation,

not assimilation-blberation, not equality—inspire and remind us that we are

not alone, Raising radical (from the root) questions creates more opportunities

for solidarity, nore sites for bulging community, and more people to joyfully

‘work alongside. We can build the communities we know we need, and leave no

‘one behind along the way. During the 2012 strike, the Chicago Teachers Union

rejected aitempts to divide working and poor patents, often people of color, from

Public schoolteachers, and countered claims that edueatars eared more about

benefits and salaries than the weil-being of Chicago’ children. Good teaching

conditions are good learning conditions, they insisted, We insist om this too, and

‘on an expanded version ofthe idea: The conditions for flourishing lives are exactly

‘the same as the conditions for justice. 1 wil take all of us to do the work to build

this world. We willbe there! Presentel

Blass, Mark, a

Sourcebook of Gi

8 Kunzel, Regina,

Lesbian Prison

9 Quinn, Therese,

Negotiating Het

School? Journal

10 Meiners, Erica. 2

of Public Bnernie

11 Lewin, Tamar, 2

New York Times,

students-face-ne

12 Hira trans-sens

pronoun.” gender

Endnotes

1 Inaugural Address by President Barack Obama, Jan, 21, 2019. whitehouse.

gov/the-press-office/2013/01/21/inaugural-address-president-barack-

‘obama

2 Strauss, Valevie. 2014, “School District Bans Discussion on Michael Brown,

Ferguson’ Washington Post, Aug. 26. vashingtonpost.com /blogs/answer-

sheet/wp/2014/08/26/school-district-bans-classro0m-diseussion-on-

ichael-beown-ferguson/

3. "Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions." 1848, Women’s Rights

Convention at Seneca Falls. eessba.rutgers.edu/docs/seneca.html

4 ‘Address athe Conclusion ofthe Selina to Montgomery March, March 26,

19652 mlk-kppot stanford.eiu/indexphpfeneyclopedia/ocumentsentry/

doe_address_at_the_conclusion_of_selma_march/

‘5 Mogul, Joey, Andrea Ritchie, and Kay Whitlock, 2011 Queer (Injustice: The

Criminatization of LGBT People in the United States. pp. 45-46, Beacon.

© Lorde, Andre. 1982. "Learning from the 60” blackpast org/1982-eudre-

Jorde-leaming-6os

7 Many representations of these movements and ideas are available in:

RETHINKING SEXISM, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY

Blasius, Mark, and Shane Phelan. 1997. We Are Everywhere: A Historical

Sourcebook of Gay and Lesbian Politics. Routledge.

‘8 Kunzel, Regina. 2008. “Lessons in Boing Gay: Queer Encounters in Gay and

Lesbian Prison Activism.’ Radical History Review 100: 11-37.

9 Quinn, Therese. 2007. “You Make Me Erect’: Queer Gitls of Color

‘Negotiating Heteronormative Leadership at an Urban All-Giel' Public

School” Journal of Gay and Lesbian Issues in Education 4.3: 31-47,

10 Meiners, Bria, 2007. Right to Be Hostile: Schools, Prisons, and the Making

of Public Enemies. Routledge,

“AL Lewin, Tamar, 2012. “Black Students Face More Diseipline, Data Suggests”

‘New York Times, March 6, nytimes.com/2012/03/06/education black-

students-face-more-harsh-diseipline-data-shows html?_r=0

12 Hir, a trans-sensitive gender pronoun. See more at“A gender neutral

| _ pronoun. genderneutralpronounwordpress.com/tagytransgender/

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

RETHINKING SEXISM,

GENDER, AND SEXUALITY

Edited by:

Annika Butler-Wall, Kim Cosier, Rachel L. S. Harper, Jeff Sapp,

Jody Sokolower, Melissa Bollow Tempel

A RETHINKING SCHOOLS PUBLICATION

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Community Mural Lesson Plan 1-4Document8 pagesCommunity Mural Lesson Plan 1-4api-645231662No ratings yet

- Curriculum Analysis MayumiDocument11 pagesCurriculum Analysis Mayumiapi-645231662No ratings yet

- First Draft of Teaching PhilosophyDocument4 pagesFirst Draft of Teaching Philosophyapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Community Mural 1Document55 pagesCommunity Mural 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- Pecha Kucha - PortraitsDocument5 pagesPecha Kucha - Portraitsapi-645231662No ratings yet

- CreatinggaylesbiansafeclassroomsDocument6 pagesCreatinggaylesbiansafeclassroomsapi-645231662No ratings yet

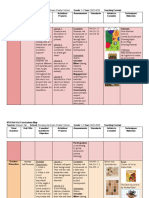

- Curriculum Map-CompressedDocument12 pagesCurriculum Map-Compressedapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Framing IdentityDocument12 pagesFraming Identityapi-645231662No ratings yet

- PuppetsDocument8 pagesPuppetsapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Human Interest Portraits Rotation 2016Document25 pagesHuman Interest Portraits Rotation 2016api-645231662No ratings yet

- Winter Wonderland-CompressedDocument10 pagesWinter Wonderland-Compressedapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Unit Title Family Portraits 1Document14 pagesUnit Title Family Portraits 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- (Mis) Information Highways: A Critique of Online Resources For Multicultural Art EducationDocument15 pages(Mis) Information Highways: A Critique of Online Resources For Multicultural Art Educationapi-645231662No ratings yet

- How The Labels in The British Museums Africa Galleries Evade Responsibility 1Document7 pagesHow The Labels in The British Museums Africa Galleries Evade Responsibility 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- WatsonwhatdoyoumeanurbanDocument7 pagesWatsonwhatdoyoumeanurbanapi-645231662No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 216.165.95.146 On Wed, 14 Oct 2020 19:17:23 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 216.165.95.146 On Wed, 14 Oct 2020 19:17:23 UTCapi-645231662100% (1)

- Gender Identity 2Document2 pagesGender Identity 2api-645231662No ratings yet

- What Is Critical Race Theory and Why Is It Under AttackDocument7 pagesWhat Is Critical Race Theory and Why Is It Under Attackapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Crtchapter 1 WhatiscrtDocument8 pagesCrtchapter 1 Whatiscrtapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Everything You Think You Know About Identity Politics Is Wrong Plan A MagDocument12 pagesEverything You Think You Know About Identity Politics Is Wrong Plan A Magapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Meet The Teacher Mayumi or MsDocument6 pagesMeet The Teacher Mayumi or Msapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Economic Class Identity 1Document2 pagesEconomic Class Identity 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- Autohistoria Poem 1Document1 pageAutohistoria Poem 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- Bellstorytelling CH 1 1 1Document19 pagesBellstorytelling CH 1 1 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- Moving From Safe Classrooms To Brave Classrooms AdlDocument3 pagesMoving From Safe Classrooms To Brave Classrooms Adlapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Why Is This The Only Place in Portland I See Black People - Rethinking SchoolsDocument21 pagesWhy Is This The Only Place in Portland I See Black People - Rethinking Schoolsapi-645231662No ratings yet