Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bellstorytelling CH 1 1 1

Bellstorytelling CH 1 1 1

Uploaded by

api-6452316620 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

75 views19 pagesOriginal Title

bellstorytelling ch 1 1 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

75 views19 pagesBellstorytelling CH 1 1 1

Bellstorytelling CH 1 1 1

Uploaded by

api-645231662Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

{ 1

: (CRITICAL TEACHING ABOUT Racism

I I THROUGH STORY AND THE ARTS

Introducing the Storytelling Project Model!

| when we begin to see ourselves as contributing to a fabric, we are no

| fJonger invisible threads or entire bolts full of lonely self-importance

(White student, 1995)

| the quote above comes from a paper written fora course in quali-

tative research where for two semesters we conducted interviews

Shout race and racism in the United States with people working in

‘education and human services (see L.A. Bell, 2003a). As we ana-

Iyzed the transcripts of these interviews, I noticed how often people

draw on stories to explicate their views about race, and the persis-

tent ways that certain stories repeat, uttered as individual but pat-

terned across multiple interviews. I also noticed that students who

‘were more knowledgeable and conscious about racism (more often,

though aot exclusively, students of colo), were able to comment on

| the racial assumptions embedded in stories in ways that enabled less

aware classmates to discern racism through the vehicle of the words

| Spread before them. When white students recognized themselves in

| these stories, for example, they were more open to reflecting on their

| vow cacial socialization in critical ways. Italso seemed that students

| Sr color could point out the racist content of interviews without feel-

ing they had to temper their insights to avoid defensiveness from

‘white classmates. In one such discussion, a young white man com~

vented in fascinated, dawning awareness, “Tve said that before!” as

he began to recognize and consider racial assumptions pointed out in

the eranscript he and an African American classmate were analyzing,

I

10 THE STORYTELLING PRosecT movEL

‘The focus on the words and Stories of others prompted some of the

least defensive, most honest and genuine ‘conversations about rac

Thave witnessed in my teaching life,

Thave been learning and teaching about racism for the pase thirty

Foon app erimenting with pedagogical approaches to rasisn aed other

recruitment into whiteness, I have facilitated numerous courses and

jorkshops on this topic in both all-white and mined save roups and

have witnessed the confusion, guilt, anger and resistance that many

for using that story type to explore race and racism,

UNG PROJECT MoDeL

“el a Prompted some of the

3 Wersations about racism

hing about r

c ruc for th

i ne past thir

i a approaches to racism andothe,

how ie Fe teaching tols the

¥y own socialization and ongoing

« filed numerous aie eal

Lire and mixed race gro fe nT

ils, anger an, me

reg RBet and resistance that ma

at they have been socialized inne,

inges frustration and dsl 2m

ho dub that theit own stores and

4d pe understood. Though aay

vale coonited enti

wa challenges of helping seudens

tre of racism in their lives

4 words of othe

‘others sometimes

gue about racism and tel =

‘mic nature of white :

a ite supremac

his approach enable some wha,

ty in the racial system, and he

hemselves as human beings, as

Bite opening of this chapter?

+ Storytelling Project described

Ip su.

Yelling Project and the devel

‘ching about race and raion

cS the process through which

rn 7p use as constructs

e central role of

tration This dics g

at define in more detail each

Sand activities we

ind racism, teaped

i THE STORYTELLING PROJECT MODEL WW

the Storytelling Model

F cessing

Kurt Lewin once said thar there is nothing so practical as a good

rrory (Lewin, 1952). Our goals forthe Storytelling Project were to

he arts, and story in particular, to teach/learn about

to develop practical pedagogical tools for teach-

ing about racism that could be extended to other areas of socal jus-

tie, replicated and adapted for a range of purposes and groups. We

focused on strategies for curricular and professional development that

stould engage people both in critical examination of racism and in

finding proactive ways to work against racism in their own commu-

nities. The Storytelling Model that emerged from this process views

pice and racism through four story types, drawing on multiple artistic

and pedagogical tools to discover, develop and analyze stories about

racism that can catalyze consciousness and commitment to action.

‘Our creative team of artists, educators, academics and under-

graduate students met monthly for intensive full-day exploration and

discussion of racism through various art forms. This incredibly gen-

trative process was facilitated by a grant from the Third Millennium

Foundation and space for our work at their International Center for

Tolerance Education (ICTE). Housed in a renovated warchouse in

the DUMBO area of Brooklyn, ICTE provided a bright and open

space, filled with art and surrounded by an expanse of river and sky

visible from every window. Once a month we converged on this space

to engage pedagogical and artistic processes for exploring racism.

‘Ourstarting point was a social justice education paradigm that looks

at diversity through the structural dynamics of power and privilege,

‘We were concerned with both diversity—how race is constructed as

a form of difference—and social justice—the unequal ways in which

social hierarchies sort difference to the benefit of some groups over

others (Adams, Bell & Griffin, 2007). Using this focus we explored

how racial stories and storytelling both reproduce and challenge the

racial status quo and how methods derived from storytelling and the

arts might help us expose and constructively analyze pervasive pat

terns that perpetuate racism in daily life. We examined the power in

stories and the power dynamics around stories to help us understand

how social location (our racial position in society) affects storytelling

I

experiment with t

race and racism, and

12 THE STORYTELLING PROJECT MODEL

and to consider ways to generate new stories that account for power,

privilege and position in discussing and acting on racial and other

social justice issues. In particular, we wanted to expose and confront

color-blind racism and develop tools to tackle racial issues consciously

and proactively in a racially diverse group.

In our collective reading we examined theoretical ideas about race

(identity, positionality, racial formations) and racism (power, privi-

lege, resistance, collusion). When we came together each month we

explored these ideas through the creative vehicles of poetry, writing,

dance, spoken word, theater games, film and visual art. Ateach meet.

ing, we experientially engaged one or more art forms, reflected on our

experiences with these forms and discussed the issues thus raised for

understanding race and racism. We came to see this as a collabora-

tive theory building process (Murray, 2006) where we put forth and

tested out ideas for understanding and teaching about race and rac-

ism through the arts. This collaborative process, described in detail

in Bell and Roberts (2010), drew upon the knowledge, expertise and

lived experiences of creative team members and used our diverse racial

locations and perspectives to create the Storytelling Project Model.

Understanding Race and Racism

Four key interacting concepts undergird how we understand race

and racism: race as a social construction, racism as a system that

operates on multiple levels, white supremacy/white privilege as key

though often neglected aspects of systemic racism, and the problem

notion of color-blindness as an ideal and barrier to racial progress

Our thinking about each of these concepts was influenced by a ange

of resources and writing that I discuss briefly below.

Race as a Secial Construction

‘We understand race as something that is created through the assump-

tions, norms and patterns human beings assign to it rather than as a

naturally fixed and given category (Omi & Winant, 1986). We recog-

nize that all people are members of a human community that shares

the same biological characteristics, exhibiting more variation within

|

|

|

|

|

tune

‘OJECT MoveL

‘ate Phil ‘stories that accour

using and acting on traci

lar, we wanted t0 expose

tools to tackle racial issues

“erse group,

examined theoretical

ical ideas a

armations) and racism (po Sins

ema) wer, priv

" a ime together each on:

‘ a vehicles of poetry, tin ie

es, film and visual art. Ateach mace”

a6 ut. At each meet-

‘More art for

4 discussed the ns ther ni

i s thus raised for

a came to see this as a eiaige

ray, 2006) where we put forth and

'8 and teaching about race and

rorative process, described in deveil

‘upon the knowledge, expertise ed

nembers and used our diverse racial

€ the Storytelling Project Model

nt for power,

ial and other

and confront

8 consciously

dergitd how we understand

uction, racism tar

as a syste

“premye peg

Ystemic racism, and the probleme,

deal and barrier to aca a

oncepts was influe os

Sse belowe ny 2 BE

tis created through the assum

wi fe Winant, 1986). We recog-

pe community that shares

ing more variation within

THE STORYTELLING PROJECT MODEL 13

J go-called racial groups than between groups (Gould, 1996) and that

seamonly held concept of different “races” is in fact, am illusion

(Adelman, 2003; Haney-Lopez, 2006). However, we also recognize

(the idea of race powerfully shapes the intimately lived exper

trees of people assigned t0 various racial categories (Fine, 1997).

Racial identity is not merely an instsument of rule; iis also an arena

rad medium of social practice. Its an aspect of individual and collec:

‘ve selthood. Racial identity in other words does al srt of practical

work’ it shapes privileged status for some and undermines the socal

sanding of others, It appeals to varied political constituencies, inclo~

shee and exclusive. Ie codes everyday life in an infinite number of ways

(Winant, 2004, p. 36)

‘Though constructed through ideas and language, rather than biology,

race has significant material consequences in the real world.

Racism as a System that Operates om Multiple Levels

We conceptualize racism as a system of interpersonal, socal and

institutional patterns and practices that maintain social hierarchies

in which Whites as a group benefit at the expense of other groups

Inbeled as “non-white’—African Americans, Latinos, Asian Ameri-

cans, Native Americans, and Arab Americans (L-A. Bell, 2007

Hardiman & Jackson, 2007). We understand racism as a phenome-

non that operate historically to sustain and inform the present, but in

sways that often don't leave tracks (Winant, 2004), Because it saturates

var institutions and social structures itis like the water in which we

the ar that we breathe (see Tatum, 2003). It shapes our govern

swim;

jusinesses, media and other social institu-

ment, schools, churches, b

tions in multiple and complex ways that serve to reinforce, sustain and

continually reproduce an unequal status quo (Bell, Love & Roberts,

2007). As a system that has been in place for centuries, “business as

“sual” is sufficient to fuel an institutionalized system of racism that

often operates outside of conscious or deliberate intention. Because

wwe must understand its ubiquity in order to effectively challenge its

hegemony, the quotidian vehicle of story offers a promising way t Bet

at the commonplace of racism in daily life.

|!

14 THE STORYTELLING PROJECT MODEL

Conscious awareness of racism varies widely among different racial

groups, however, and thus shapes the stories to which each group has

access (van Dijk, 1999). Whites as a group tend to be less conscious

of racism and/or more likely to believe that racism has been addressed

than people of color who experience the ongoing effects of racism

daily in their lives (L.A. Bell, 2003a; Bonilla-Silva, 2003, 2006a;

Myers, 2005; Solorzano, Ceja & Yosso, 2000). Because racial loca.

tion so powerfully shapes the stories we hear and tell about racism,

wwe thought a great deal about how to account for positionality as we

developed the Storytelling Model.

White Supremacy and White Privilege

Race has inescapable material consequences in society, shaping access

to resources and life possibilities in ways that benefit the white racial

group at the expense of groups of color (Katznelson, 2005; Lipsitz,

2006; Marable, 2002; Massey & Denton, 1993; Oliver 8 Shapiro,

1997). The racially shaped distribution of resources is illustrated quite

Powerfully in a DVD we watched and discussed as a creative team in

one of our early sessions: “Race: The Power of an Illusion” (Adelman,

2003). This excellent DVD provides a historical and sociological lens

for dissecting ideas about race and tracing the consequences of these

ideas in American society.

Many recent scholars describe well how whiteness works as the

{unmarked but presumed norm against which people from other groups

are measured (Berger, 1999; Dyer, 1997; Fine, 1997; Frankenberg,

1993, 1997; Hitchcock, 2002; Myers, 2005). Positioning whiteness as

a central feature in the study of racism enables us to identify the power

dlynamics and unearned advantages that accrue to Whites asa group

(Frankenberg, 1997; Katznelson, 2005; Kendall, 2006; Lipsitz, 2006;

‘McIntosh, 1990; Oliver & Shapiro, 1997; Wise, 2005). We wanted

to unearth stories that expose normative practices that are marked as

neutral in order to shine a spotlight on institutions that maintain and

bolster white supremacy and to open up analytic possibi

lenging its hegemony.

> experience the o

eee

‘munity in which race and racism can be openly discussed, each per=

on’s voice and story can be respectfully heard, stories can be held up

and scrutinized in terms of their relationship to systems of power and

privilege, and practices of power that differentially privilege or mute

particular stores (thus reproducing the system we hope to dismantle)

tan be interrupted. For example, white people are often confront

ing the realities of racism for the first time, realities that are all too

familiar to people of color. Ground rules need to acknowledge these

differences and find ways to validate and learn from what different

positions/locations teach us about how the system of racism works

‘We set forth these intentions with the group and engage them in

naming and practicing guidelines that support these intentions so that

when conflicts or disagreements arise the guidelines can be used to

facilitate thoughtful face-to-face discussion and engagement. While

specific guidelines will likely differ from group to group, what matters

is that they are intentionally generated to acknowledge differences in

power and privilege and to equalize and encourage shared risk-taking.

Tis also critical that the guidelines be conscientiously used to facili-

tate honest dialogue and to recognize and stick with uncomfortable

‘moments particularly at the first sign of conflict or disagreement.

Establishing such a community is an essential foundation for effec

tively using the Storytelling Model (sce Chapter 6 for a fuller discus

sion and illustration of the model in practice).

22 THE STORYTELLING PROJECT MODEL

Developing the Story Types

‘The creative team continually discussed the limitations and opportu-

nities provided by stories to get at what we began to cal “the genealogy

of racism.” We engaged in storytelling, mining our own experiences

through writing and poetry and through reading stories and poetry

written by others. This process raised provocative questions about the

complications of storytelling: stories can be truthful but can also be

‘masks; they can allow us to take on the burdens of racism as well as

escape thinking about it; because our identities are multiple our stories

also speak to this multiplicity, complicating racism and its intersee.

tions with other aspects of social inequality. We found that some-

‘times telling our stories in the group could help us remember what we

had forgotten as individuals about the pains of racism, the rewards of

Privilege and the normative discourses that make conscious, honest

dialogue about racism so difficult to sustain. We grappled with the

challenges of using story to unearth socio-cultural practices in a soci.

ety that valorizes individualism,

Through these conversations we began to differentiate types ofsto-

ries. The idea of contrasting hegemonic or stock stories with counter

Stories (LA. Bell, 2003a) was one starting point. We began to flesh

out these two story types in our storytelling experiments. We also

looked to history, visual art, poetry and literature for inspiration, as

wel as to the notion of counter storytelling in critical race theory.

‘These explorations led us to consider and differentiate concealed sta.

fies held within oppressed communities that are often hidden or pro-

tected from outside scrutiny, as well as to stories of challenge and

resistance,

‘The model we ended up with codifes four story types to describe

hhow people talk and think about race and racism in the United States

‘These are: stock tories, concealed stories, resistance stories and emerg-

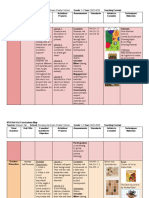

ing/transforming stories.? As Figure 1.1 shows, building a counter-

Storytelling community is central to exploring the four story types.

We conceive of these stories as connected and mutually interaeting,

Each story type leads into the next ina cycle that ills out and expands

our understanding of and ability to creatively challenge racism, The

Story types provide language and a framework for making sense of

ING PROJECT MooEL

cae the limitations and oppor

tae began to call “the eencligy

Stings mining our own experien =

rough reading stories ey

ised provocative ques

ies ca

and

ies and poetry

questions about the

a as be truthful but can also im

on the burdens of acim aswell ag

se ea are multiple our stories

nplicatng racism and its intesec-

equality. We found that some.

3 eu el us remember what

Pains of racism, the rewards of

We that make conscou homer

to sustain, We ith the

sustain. We grappled with the

socio-cultural practices in a s

gan to differentiate ty

nk or sock tris with oureer

farting point. We began to fesh

rytelling experiments. We als,

and literature for adie, ‘

rytelling in critical race datory

and differentiate concealed sto-

¢s that are often hidden or pro-

35 to stories of challenge and

ies our ory types to describe

‘Ad racism in the United States,

°S, resistance stories and, :

emerg.

1 shows, building a counes.

"olin the ou sry pe

and mutually interacting,

yele that flout and expand,

atively challenge racism, The

mework for making sense of

THE STORYTELLING PROJECT MODEL 23

ij racism through exploring the genealogy of racism and the

race ant

rail stories that generate and reproduce it through the stock stories

that keep it in place.

‘Stock stories arc introduced as the fist type because they are the

snost public and ubiquitous in the mainstream institutions of soci-

fry—schools, businesses, government and the media—and because

other story types, as counter-stories, critique and challenge the

presumption of universality instock stories, Thus, they provide the

ground agtinst which we build our analysis, Stock stores a the tales

Bid by the dominant group, passed on through historical and literary

vJocurments, and celebrated through public rituals, law, the arts, ed~

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Community Mural Lesson Plan 1-4Document8 pagesCommunity Mural Lesson Plan 1-4api-645231662No ratings yet

- Curriculum Analysis MayumiDocument11 pagesCurriculum Analysis Mayumiapi-645231662No ratings yet

- First Draft of Teaching PhilosophyDocument4 pagesFirst Draft of Teaching Philosophyapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Community Mural 1Document55 pagesCommunity Mural 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- Pecha Kucha - PortraitsDocument5 pagesPecha Kucha - Portraitsapi-645231662No ratings yet

- CreatinggaylesbiansafeclassroomsDocument6 pagesCreatinggaylesbiansafeclassroomsapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Curriculum Map-CompressedDocument12 pagesCurriculum Map-Compressedapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Framing IdentityDocument12 pagesFraming Identityapi-645231662No ratings yet

- PuppetsDocument8 pagesPuppetsapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Human Interest Portraits Rotation 2016Document25 pagesHuman Interest Portraits Rotation 2016api-645231662No ratings yet

- Winter Wonderland-CompressedDocument10 pagesWinter Wonderland-Compressedapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Unit Title Family Portraits 1Document14 pagesUnit Title Family Portraits 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- (Mis) Information Highways: A Critique of Online Resources For Multicultural Art EducationDocument15 pages(Mis) Information Highways: A Critique of Online Resources For Multicultural Art Educationapi-645231662No ratings yet

- How The Labels in The British Museums Africa Galleries Evade Responsibility 1Document7 pagesHow The Labels in The British Museums Africa Galleries Evade Responsibility 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- WatsonwhatdoyoumeanurbanDocument7 pagesWatsonwhatdoyoumeanurbanapi-645231662No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 216.165.95.146 On Wed, 14 Oct 2020 19:17:23 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 216.165.95.146 On Wed, 14 Oct 2020 19:17:23 UTCapi-645231662100% (1)

- Economic Class Identity 1Document2 pagesEconomic Class Identity 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- What Is Critical Race Theory and Why Is It Under AttackDocument7 pagesWhat Is Critical Race Theory and Why Is It Under Attackapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Crtchapter 1 WhatiscrtDocument8 pagesCrtchapter 1 Whatiscrtapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Everything You Think You Know About Identity Politics Is Wrong Plan A MagDocument12 pagesEverything You Think You Know About Identity Politics Is Wrong Plan A Magapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Meet The Teacher Mayumi or MsDocument6 pagesMeet The Teacher Mayumi or Msapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Autohistoria Poem 1Document1 pageAutohistoria Poem 1api-645231662No ratings yet

- SenecafallsselmastonewallDocument12 pagesSenecafallsselmastonewallapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Gender Identity 2Document2 pagesGender Identity 2api-645231662No ratings yet

- Moving From Safe Classrooms To Brave Classrooms AdlDocument3 pagesMoving From Safe Classrooms To Brave Classrooms Adlapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Why Is This The Only Place in Portland I See Black People - Rethinking SchoolsDocument21 pagesWhy Is This The Only Place in Portland I See Black People - Rethinking Schoolsapi-645231662No ratings yet