Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kelompok 5

Uploaded by

fransiskus mekuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kelompok 5

Uploaded by

fransiskus mekuCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/234070782

Interprofessional education in team communication: Working together to

improve patient safety

Article in BMJ quality & safety · January 2013

DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

267 794

10 authors, including:

Douglas Michael Brock Erin Abu-Rish Blakeney

University of Washington Seattle University of Washington Seattle

86 PUBLICATIONS 2,069 CITATIONS 33 PUBLICATIONS 944 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Chia-Ju Chiu Dana Hammer

University of Washington Seattle 25 PUBLICATIONS 1,153 CITATIONS

2 PUBLICATIONS 446 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Conciliation médicamenteuse View project

Handoffs View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Douglas Michael Brock on 06 January 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

BMJ Quality & Safety Online First, published on 3 January 2013 as 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952

INNOVATIONS IN EDUCATION

Interprofessional education in team

communication: working together to

improve patient safety

Douglas Brock,1 Erin Abu-Rish,2 Chia-Ru Chiu,2 Dana Hammer,3

Sharon Wilson,2 Linda Vorvick,1 Katherine Blondon,4 Douglas Schaad,5

Debra Liner,2 Brenda Zierler2

1

Department of Family Medicine ABSTRACT Conclusions Effective team communication is

and MEDEX Northwest, Background Communication failures in important in patient safety. We demonstrate

University of Washington,

Seattle, Washington, USA healthcare teams are associated with medical errors positive attitudinal and knowledge effects in a

2

Department of Biobehavioral and negative health outcomes. These findings have large-scale interprofessional TeamSTEPPS-based

Nursing, University of increased emphasis on training future health training involving four student professions.

Washington, Seattle,

professionals to work effectively within teams. The

Washington, USA

3

Department of Pharmacy, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance

University of Washington, and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) communication INTRODUCTION

Seattle, Washington, USA training model, widely employed to train An increased focus on interprofessional

4

Department of Health Services,

University of Washington,

healthcare teams, has been less commonly used education (IPE) has resulted from several

Seattle, Washington, USA to train student interprofessional teams. The influences. Among the most compelling is

5

Department of Biomedical present study reports the effectiveness of a the growing recognition and evidence

Informatics and Medical simulation-based interprofessional TeamSTEPPS that improved communication and col-

Education, University of

Washington, Seattle,

training in impacting student attitudes, laboration by interprofessional teams

Washington, USA knowledge and skills around interprofessional leads to better delivery and access to care.

communication. In its 2004 sentinel event data report,1

Correspondence to

Methods Three hundred and six fourth-year the Joint Commission listed leadership,

Dr Douglas Brock, Department

of Family Medicine and MEDEX medical, third-year nursing, second-year pharmacy communication, coordination and human

Northwest, University of and second-year physician assistant students took factors as among the leading root causes

Washington, 4311-11th Ave NE, part in a 4 h training that included a 1 h of sentinel events. Failures in communica-

Suite 200; Seattle, WA 98195,

USA;

TeamSTEPPS didactic session and three 1 h team tion within interprofessional healthcare

dmbrock@u.washington.edu simulation and feedback sessions. Students worked teams are established causes of medical

in groups balanced by a professional programme in error2 and negative health outcomes,1 3 4

Received 1 March 2012 a self-selected focal area (adult acute, paediatric, including death.5 In addition, team com-

Revised 10 October 2012

Accepted 14 November 2012 obstetrics). Preassessments and postassessments munication failures have significant eco-

were used for examining attitudes, beliefs and nomic impacts that may reduce quality

reported opportunities to observe or participate in and safety, or access to care.1 6

team communication behaviours. The relationship between team commu-

Results One hundred and forty-nine students nication and patient safety4 has increased

(48.7%) completed the preassessments and the emphasis placed on training future

postassessments. Significant differences were health professionals to work within

found for attitudes toward team communication teams.7–9 However, few studies have

(p<0.001), motivation (p<0.001), utility of training sought to demonstrate that prepractice

(p<0.001) and self-efficacy (p=0.005). Significant interprofessional team training is effective

attitudinal shifts for TeamSTEPPS skills included, in building the foundations for later prac-

team structure (p=0.002), situation monitoring tice within healthcare teams. Increasingly,

(p<0.001), mutual support (p=0.003) and educators have sought to create interpro-

To cite: Brock D, Abu-Rish E, communication (p=0.002). Significant shifts were fessional trainings that teach the key ele-

Chiu C-R, et al. Quality and

Safety in Health Care

reported for knowledge of TeamSTEPPS (p<0.001), ments of effective teamwork in simulated

Published Online First: [ please advocating for patients (p<0.001) and settings that allows for the practise of skills

include Day Month Year] communicating in interprofessional teams in a stimulus-rich but controlled environ-

doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012- (p<0.001). ment. Interprofessional team simulation

000952

Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 1

Copyright Article author (or their employer) 2013. Produced by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd under licence.

Innovations in education

designed to promote incorporation of team communica-

tion into programme curricula across the health profes-

sion schools.

Interprofessional team communication is defined by

skills learned and later modified and reinforced when

healthcare workers work collaboratively to provide

competent care. Competence to practise safely

requires effective communication with patients and

colleagues, active listening, assertiveness, respect and

timeliness. Failures occur when vital information is

not communicated between team members, or team

members incorrectly interpret messages. Failures to

communicate information may result from adversarial

relationships, roles that are not clearly defined, or

insufficiently developed communication pathways

within teams. Incorrect interpretations occur when

Figure 1 Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance providers use different terms to convey information,

and Patient Safety communications model. accept incomplete information, or assign different

weights to communications. In each case, the result

provides a means to both learn and practise safe team- may be an error.

work skills. The educational framework for the development of

With this paper, we describe a sophisticated inter- the training content was based on TeamSTEPPS.12

professional team-based training, and take the import- TeamSTEPPS was developed from research and devel-

ant first step of demonstrating that participating opment collaborations between the Department of

students can learn critical elements of team communi- Defense (DoD) Patient Safety Program and the Agency

cation, and to value team functioning. We also dem- for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and is

onstrate the utility of new self-report instruments. rooted in crew resource management13–15 (CRM).

Our study employs an established team communi- Increasingly, there are calls for the incorporation of

cation framework,10 11 Team Strategies and Tools team training into clinical settings16 stemming from

to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety successful applications within surgery and trauma-

(TeamSTEPPS),12 in teaching skills using manikin focused settings.17–19 More recently, clinician educa-

simulators and standardised patients. While excep- tors have sought to integrate TeamSTEPPS tools11 16)

tions exist, training efforts commonly neglect to into healthcare education. Simulation-based training

provide evidence that learning has occurred, and that provides an excellent vehicle for student teams to work

learning is transferable to clinical settings. The collaboratively in a realistic yet structured environment

purpose of this paper is to describe and demonstrate without risks to patients.20–22

the effectiveness of an innovative interprofessional

training effort using simulation.

Study goals

BACKGROUND The overall goal of the interprofessional training was

The curriculum and assessment tools described in this for students to acquire effective interprofessional team

study were developed as part of a grant funded through communication skills. Taking part in these exercises

the Josiah Macy Jr Foundation for the purpose of allowed students the opportunity to practise and

improving communication within learning teams, observe interprofessional communication, and

enhancing team-based care, increasing awareness of through facilitated debriefings learn what proved most

respective roles and responsibilities, and promoting an effective. Our study goal sought to demonstrate that

understanding of interprofessional values and ethics. interprofessional students would report enhanced

Faculty from the schools of medicine, nursing, phar- readiness23 through improved self-efficacy,24 25 motiv-

macy and the MEDEX Northwest Physician Assistant ation, positive attitudes and practice opportunities.

(PA) Training Program worked to create novel and dis- We proposed assessing testable research questions

tributable training tools for team communication aimed aligned with our training goals. Following training,

at reducing errors and improving patient safety. The would interprofessional students report

goal was to create new collaborations, while strengthen- 1. Improved attitudes, motivation and self-efficacy to

ing and leveraging existing interprofessional activities— working within interprofessional healthcare teams?

where students from different disciplines work 2. Having observed and practised key team communication

together—and intraprofessional activities—where stu- skills?

dents work only with students within their discipline— 3. Increased understanding of interprofessional team skills?

2 Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952

Innovations in education

METHODS exercises. Following an icebreaker activity developed

Case development to introduce interprofessional teamwork, students had

Three adult acute cases (two adult males and one 40 min of didactic instruction on patient safety and

teenage male) to demonstrate communication across TeamSTEPPS communication skills.

members of a healthcare team were developed collab- For the simulation sessions, students were divided

oratively by a team of 9 interprofessional faculty, 19 into interprofessional teams with balanced compos-

student volunteers from various health profession pro- ition across healthcare programmes. The teams then

grammes and 6 staff members. They were designed to completed three simulated exercises (approximately

provide opportunities for an interprofessional team to 15 min each). Two exercises used a manikin simulator

demonstrate team communication strategies and skills and a standardised family member, and the third used

in an acute situation, while delivering care to patients only a standardised patient. Each simulation was pre-

and their families. The three adult acute cases were: ceded by an introduction (eg, case materials and

asthma exacerbation in a teenager (simulator with ground rules), and was followed immediately by a

standardised family member), congestive heart failure facilitated debriefing session. When not actively par-

in an elderly male (standardised patient) and supra- ticipating in a simulation, or when there were too

ventricular tachycardia in a male postsurgery (simula- many students to accommodate, students were asked

tor with standardised family member). Each of the to step back and observe. Students rotated through

three adult acute cases, and an adapted TeamSTEPPS observer and participant roles throughout the three

training, were tested with 49 students in June 2010. cases. All students (observers and participants) partici-

Following the successful demonstration of the three pated in the end-of-case debriefings. Student teams

adult cases, we designed three paediatrics and three met again as a large group for a final wrap-up with

obstetrics cases to reflect parallel skills requirements, the facilitators to review what they had learned.

and provide comparable team communication skills

training in areas aligned with students’ career plans. Measuring the intervention’s impact

The paediatric cases were: severe asthma, acute To assess the impact of the training on student learning,

seizure and sepsis (each using a simulator). The three we developed and selected instruments to assess atti-

obstetric cases were precipitous vaginal delivery, mild tudes, skills and knowledge (table 1). Instruments were

postpartum haemorrhage and mild postpartum haem- developed and reviewed by the UW Macy assessment

orrhage complicated by error (each using a standar- team, consisting of a physician and PA educator (LV), a

dised patient). Each of the cases are described and visiting physician fellow (KB), a nurse practitioner (SW),

available with toolkits for implementing and develop- a pharmacist (DH), two medical educators (DB, DS), a

ing simulations on the Center for Health Sciences nursing educator (BZ) and two nursing graduate stu-

Interprofessional Education, Practice and Research dents (CC, EAR). These instruments included attitudes

website (http://www.collaborate.uw.edu). towards TeamSTEPPS communication skills, self-

reported knowledge, motivation to implement these

Interprofessional Team Capstone skills, their value or utility and student self-efficacy in

We used an existing capstone week held by the being able to implement these skills in practice.

University of Washington School of Medicine during Student respondents were described by several

the last week of classes as an opportunity to bring demographic variables. These included the student

graduating medical bachelors of science in nursing, educational programme, sex, age, healthcare experi-

PharmD and masters PA students together for inter- ence prior to entering their current educational pro-

active interprofessional training sessions. Participation gramme, and previous familiarity in working with

in the interprofessional training was required for all healthcare teams (eg, respiratory tech or medic).

students except for the PA students who were volun- Two instruments were administered, both pretrain-

teers. Students participated in one 4 h training block ing and post-training. To assess attitudes towards team

during the capstone week. communication we administered the TeamSTEPPS

The Interprofessional Team Capstone experience Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (TAQ).26 The

was designed to train students from four healthcare TAQ is a validated instrument containing 30

professional programmes to practise together as a Likert-type items assessing attitudes towards the five

team. Students had the option to participate in one of dimensions (Team Structure, Leadership, Situational

three separate (focal area) trainings: (1) adult acute Awareness, Mutual Support and Communication)

care (2) paediatric, or (3) obstetric cases. This break- underlying the TeamSTEPPS communications model.

down allowed students to select an area of practice Attitudes were assessed by the Attitudes, Motivation,

most similar to their anticipated specialty. The training Utility and Self-Efficacy (AMUSE); a 21 Likert-type

sessions occurred at two academic medical centre item instrument constructed to assess AMUSE. The

training facilities across a 4-day period. In each attitudes, motivation and utility items were developed

student focal area, the educational intervention by the authors in consideration of existing instruments

included a didactic session and three simulated to assess similar team constructs.23 27–30 The self-

Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 3

Innovations in education

Table 1 TeamSTEPPS communication behaviours and assessment instruments

Preinstruments and postinstruments

TeamSTEPPS: Teamwork Attitudes 30 Likert-type items (1=Strongly Disagree, to 5=Strongly Agree) assessing attitudes towards the five dimensions

Scale (TAQ)26 (Team Structure, Leadership, Situational Awareness, Mutual Support and Communication) underlying the

TeamSTEPPS communications model

AMUSE* 21 Likert-type items (1=Strongly Disagree, to 5=Strongly Agree) assessing Attitudes, Motivation, Utility and

Self-Efficacy toward interprofessional team skills

Postonly instruments

Key communication behaviours: 15 self-report frequency items, asking the extent to which the training cases provided the opportunity to practice

frequency* or observe key communication behaviours. Response options ranged on a 5-point scale from ‘Never’ to

‘Frequently’. Examples included whether team members ‘… were consulted for their experience’ or ‘… asked

for assistance’

Key concepts: understanding* 10 Likert-type item pairs (1=Strongly Disagree, to 5=Strongly Agree). Instrument asked respondents to rate their

understanding of key concepts both before and after training (eg, ‘BEFORE participating in training I had a good

understanding of the benefits and application of SBAR’ and ‘AFTER completing the training I have a BETTER

understanding of the benefits and application of SBAR’)

Training program evaluation

Participant evaluations* Completed by all students following the simulation training.

1. Report of training value by programme segment (eg, TeamSTEPPS introduction, final debrief) (1=Not at all

valuable, to 5=Highly valuable)

2. Likert-type items (1=Strongly Disagree, to 5=Strongly Agree) addressing level of agreement with specific

aspects of the training. For instance, whether the programme provided a realistic experience of the challenges

faced when working in interprofessional teams

3. Students were also asked to describe their most valuable learning experience in the training

*Developed by study team.

†Copies of all instruments available at: http://www.collaborate.uw.edu/educators-toolkit/tools-for-evaluation.html-0

TeamSTEPPS, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

efficacy items were guided by Bandura’s recommenda- for-evaluation.html-0). The presurveys and postsurveys

tions for developing scales to assess efficacy31 and fol- were completed online and generally took between 10

lowing Bandura’s theory of agency,25 32 that people and 15 min to complete. Pretraining surveys were open

act on their environment, set goals and monitor pro- to students for 2 weeks prior to training until 2 days

gress, learning both through direct experience as well prior to the training. Post-training online surveys were

as vicariously through observing others. completed either on the day the subject completed

Two new instruments and the AMUSE were developed training, or approximately 2 weeks post-training. For

specifically to assess whether students had the opportun- logistical reasons, we were unable to have students com-

ity to practise or observe specific team behaviours, and plete multiple postassessments. Students were randomly

whether these training opportunities were positively assigned to the group that completed the survey on the

regarded, and represented skills that students believed day of the training, or to the group that completed the

would be of value to carry forward, and for which they survey 2 weeks post-training. This allowed us to assess

had sufficient familiarity to successfully implement in degradation of training effects over time. All procedures

practice. One instrument asked students to report the were approved by the University of Washington

frequency with which the training cases provided the Institutional Review Board.

opportunity to practise or observe key communication

behaviours. Examples included whether team members Statistical analyses

‘… were consulted for their experience’ or ‘… asked for Statistical analyses and instruments were selected to

assistance’. This scale consisted of 15 items with align with the training goals. Within-group differences

response options ranging on a 5-point scale from (pre vs post) were analysed using paired t tests. Analysis

‘Never’, to ‘Frequently’. A second instrument asked of variance (ANOVA) was used to explore differences

respondents to rate their understanding of key concepts across interprofessional student groups (eg, medical).

both before and after training (eg, ‘BEFORE participat- Instrument internal consistency was assessed using

ing in training I had a good understanding of the benefits Cronbach’s α. All tests applied a p=0.05 level of signifi-

and application of Situation, Background, Assessment, cance. When multiple tests were performed simultan-

Recommendation (SBAR)’ and ‘AFTER completing the eously, the critical values were adjusted using the

training I have a BETTER understanding of the benefits Bonferroni criterion to reduce risk of Type I error.

and application of SBAR’). This instrument consisted of

10 item-pairs on a five-point scale from ‘Strongly RESULTS

Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’. Copies of each of the Demographics

instruments are available at the following website: A total of 306 fourth-year medical, third-year nursing,

(http://www.collaborate.uw.edu/educators-toolkit/tools- second-year pharmacy and second-year PA students

4 Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952

Innovations in education

Table 2 Number and percent of students completing preassessment and postassessments

Completed Completed Completed preassessment Completed

Total n (%) preassessment postassessment and postassessment neither

Medicine 174 (56.9) 89 (51.1) 122 (70.1) 73 (42.2) 36 (20.7)

Nursing 88 (28.8) 58 (65.9) 62 (70.5) 46 (52.3) 14 (15.9)

Pharmacy 32 (10.5) 27 (84.4) 27 (84.4.) 23 (71.9) 1 (3.1)

Physician assistant 12 (3.9) 11 (91.7) 8 (66.7) 7 (58.3) 0 (0.0)

Total 306 (100.0) 185 (60.5) 219 (71.6) 149 (48.7) 51 (16.7)

completed the training. Of the total, 255 (83.3%) stu- internal consistency. Change scores were used to

dents completed the preassessment and/or the postas- assess impact. Inspection of table 4 indicates that sig-

sessment, of which 149 (48.7%) students completed nificant positive changes occurred for the AMUSE

both the preassessment and postassessments (comple- total score ( p<0.001), and each of the four AMUSE

ters). Table 2 provides a breakdown of the student subscales ( p<0.001 to p=0.005). This provides evi-

completers by professional programme. There was no dence that training increased students’ positive atti-

significant difference, by profession, for completer tudes towards working in teams, that students were

classification (χ²=5.33, p=ns). Completers did not more motivated to work in teams, saw greater value

differ significantly from non-respondents or students (utility) to this type of training and practice and felt

completing only one assessment component on profes- able to implement the skills they had learned (self-

sion, sex, age or previous healthcare experience (each efficacy). The largest effect was seen for the AMUSE

p=ns). Therefore, the analyses reported here reflect utility score (mean=0.41, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.50). The

those students who completed both preassessment and smallest effect was seen for the AMUSE self-efficacy

postassessments, allowing for a preassessment vs post- score (mean=0.12, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.21). Individual

assessment comparison on study variables. Table 3 pro- students tended to show improvement in their atti-

vides a breakdown of the completers by sex, age and tudes, motivation, beliefs about utility and self-

healthcare, and healthcare team experience. efficacy; this effect was relatively uniform across the

Postassessments were completed in one of two professional programme and focal area.

groups: day of the training, or 2 weeks post-training. Table 4 also provides the prescores and postscores

Change scores for aggregate measures between preas- for the TeamSTEPPS Attitude Questionnaire (TAQ).

sessment and postassessment were compared using One TAQ subscale (Mutual Support) exhibited mar-

one-way ANOVA. After adjusting for the possibility of ginal internal consistency (α=0.62). The other TAQ

an inflated Type I error rate, no significant differences subscales (α=0.85–0.94) and the TAQ aggregate

were discovered as a function of the date of the postad- (α=0.93) achieved acceptable internal consistency.

ministration survey (each p>0.10). The staggered post- Significant positive increases were noted for TAQ

measures were, therefore, aggregated to a single set of Total Score ( p<0.001), TAQ Situation Monitoring

postmeasures. Only seven PA students completed both ( p<0.001), TAQ Team Structure ( p=0.002), TAQ

the preassessment and the postassessment. This number Communication ( p=0.002) and TAQ Mutual Support

was not sufficient to treat as a separate subgroup, and ( p=0.003). There was no significant change in the

the PA students were excluded from group analyses. TAQ Leadership score ( p=0.062). The largest effect

was seen for the TAQ Situation Monitoring

First training goal (mean=0.19, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.38), and the smallest

Our first training goal focused on positive attitudinal significant effect was for Communication

shifts (including motivation and self-efficacy). The (mean=0.13, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.21). Similar to the

AMUSE was used to assess changes in student atti- AMUSE results, individual students showed improve-

tudes, motivation, utility and self-efficacy following ments in most of the TAQ subscales, an effect which

training. Each subscale (α=0.90–0.79) and the aggre- was not differentially related to the student’s profes-

gate total (α=0.90) achieved acceptable levels of sional programme or the focal area of the training.

Table 3 Demographics for students completing both the preassessment and postassessments (n=149)

Medicine (n=73) Nursing (n=46) Pharmacy (n=23) PA (n=7) Total (n=149)

Sex (n (%) female) 39 (53.4) 41 (89.1) 15 (65.2) 5 (71.4) 100 (67.1)

Age (mean, SD) 28.7, 3.3 26.7, 6.5 26.6, 3.7 34.6, 5.9 28.0, 4.9

Healthcare experience (n (%) yes) 23 (31.5) 23 (50.0) 5 (21.7) 7 (100.0) 58 (38.9)

Team healthcare experience (n (%) most or Some) 21 (91.3) 16 (70.0) 1 (20.0) 6 (85.6) 44 (75.8)

PA, Physician assistant.

Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 5

Innovations in education

Table 4 Pre-Attitudes and post-Attitudes, Motivation, Utility and Self-Efficacy (AMUSE) and the TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes

Questionnaire (TAQ) Totals and subscores

Pre-Attitudes Post-Attitudes Paired Effect

Instruments Mean (95% CI) Mean (95% CI) t test Size d

AMUSE Total (n=149) 3.92 (3.85 to 3.98) 4.21 (4.13 to 4.29) 0.000 0.70

Attitudes 4.30 (4.20 to 4.40) 4.56 (4.46 to 4.65) 0.000 0.65

Motivation 3.64 (3.55 to 3.73) 4.01 (3.90 to 4.11) 0.000 0.40

Utility 4.05 (3.96 to 415) 4.46 (4.36 to 4.56) 0.000 0.70

Self efficacy 3.68 (3.60 to 3.76) 3.80 (3.71 to 3.89) 0.005 0.23

TeamSTEPPS Total (n=149) 4.02 (3.97 to 4.07) 4.16 (4.09 to 4.23) 0.000 0.32

Team structure 4.34 (4.27 to 4.41) 4.48 (4.40 to 4.57) 0.002 0.26

Leadership 4.55 (4.48 to 4.62) 4.63 (4.55 to 4.72) 0.062 *

Situation monitoring 4.33 (4.25 to 4.40) 4.52 (4.43 to 4.61) 0.000 0.35

Mutual support 3.01 (2.94 to 3.07) 3.14 (3.06 to 3.23) 0.003 0.24

Communication 3.90 (3.84 to 3.96) 4.03 (3.95 to 4.10) 0.002 0.26

*Effect size not computed for non-significant values.

All questions were scored on a scale from 1=‘Strongly Disagree’, to 5=‘Strongly Agree’.

TEAMstepps, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

One-way ANOVAs were conducted on the change differences between AMUSE subscales emerged only

scores of the TAQ and AMUSE aggregate total scores for motivation ( p=0.010, η2=0.06) and self-efficacy

and subscales to explore whether differences occurred ( p=0.005, η2=0.07). For motivation, this reflected

across student groups from different professions. lower postscores for pharmacy students (mean=3.53,

When conducting analysis by programme of study SD=0.90) than for medical (mean=4.11, SD=0.46)

(medical, nursing, pharmacy), robust statistical or nursing students (mean=4.13, SD=0.59). Medical

students (mean=3.89, SD=0.55) reported higher

Table 5 Post-training assessment of the frequency of seeing or postlevels of self-efficacy than did nursing

participating in specific behaviours (mean=3.67, SD=0.43) or pharmacy students

(mean=3.56, SD=0.73).

Item Mean (95% CI)

Second training goal

Leaders assigned tasks to team members to help 4.16 (4.05 to 4.27)

team functioning Our second training goal sought to provide students

Leaders shared information with team members 4.14 (4.04 to 4.24) the opportunity to observe and practise team commu-

Team member communication skills decreased the 4.01 (3.90 to 4.12) nication skills. In the postassessment, interprofessional

risk of errors students were asked to rate the frequency with which

Team members demonstrated a shared mental 3.92 (3.82 to 4.02) they saw or participated in a series of behaviours.

model These behaviours are provided in table 5. Since these

Team members were consulted for their experience 3.87 (3.74 to 4.00) questions could only be delivered post-training, we

Team members scanned the environment for 3.86 (3.75 to 3.97) have reported results for all students who completed

important situational cues the postassessment (n=21 971.6%). Respondents

Leaders discussed the patient’s plan with their team 3.85 (3.73 to 3.97) were significantly more likely (adjusted for Type I

Team members exchanged information with the 3.85 (3.74 to 3.96) error) to report having had the experience of team

patients and their families leaders assigning tasks and sharing information with

Leaders created opportunities for team members to 3.78 (3.66 to 3.90) team members, and to report examples of communi-

share information

cation skills that served to reduce error. Observations

Team members asked for assistance 3.73 (3.60 to 3.86)

of team members effectively asserting patient safety

Team members anticipated needs 3.71 (3.60 to 3.82)

concerns, offering each other help, or utilising

Team members asked questions about information 3.69 (3.57 to 3.81)

provided by other team members

patients and/or family members as critical members of

the care team were less likely to be reported.

Team members asserted patient safety concerns 3.64 (3.52 to 3.76)

until heard Third training goal

Team members offered help to other team members 3.53 (3.38 to 3.68) Our third training goal focused on increasing student

Patients and family members utilised as critical 3.51 (3.39 to 3.63) understanding of team skills. As part of the postassess-

components of the care team

ment, students reported levels of agreement that training

Respondents (n=194–217 completed responses per item) reported the

frequency that the training cases allowed them to practise or observe

had increased understanding of key learning objectives

instances of specific communications skills. (table 6). The largest changes occurred in beliefs around

Response options ranged from 1=‘Never’, to 5=‘Frequently’. the benefits of implementing TeamSTEPPS (mean=1.48,

6 Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952

Innovations in education

Table 6 Self-reported change between preunderstanding and postunderstanding of key TeamSTEPPS learning objectives

Learning objective Before After Change with 95% CI Paired t test Effect size

TeamSTEPPS 2.82 4.29 1.48 (1.33 to 1.63) <0.001 1.37

Advocate 3.06 4.33 1.27 (1.13 to 1.41) <0.001 1.22

Communication 3.42 4.50 1.08 (0.94 to 1.22) <0.001 1.07

Briefs and huddles 3.40 4.46 1.06 (0.93 to 1.19) <0.001 1.10

SBAR 3.45 4.46 1.03 (0.88 to 1.18) <0.001 0.92

Shared mental model 3.44 4.45 1.02 (0.88 to 1.16) <0.001 0.97

IPE benefits 3.55 4.54 0.99 (0.85 to 1.13) <0.001 0.98

Importance of sharing information 3.49 4.42 0.93 (0.81 to 1.05) <0.001 1.03

Patient safety 3.95 4.55 0.60 (0.49 to 0.71) <0.001 0.71

Offer help 4.01 4.40 0.39 (0.29 to 0.49) <0.001 0.51

Respondents (n=201–214) reported whether they had a ‘good understanding’ before training and whether they had a ‘better understanding’ after training.

Items were scored from 1=‘Strongly Disagree’, to 5=‘Strongly Agree’.

TeamSTEPPS, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

95% CI 1.33 to 1.63) and ability to advocate within- considerable logistic challenges we addressed. These

teams (mean=1.27, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.41). The least included: recruiting and scheduling students from four

change occurred in student understanding of the separate health professions; securing support from the

association between interprofessional teams and patient school deans and programme directors; recruiting suffi-

safety (mean=0.60, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.71), and of the cient volunteer faculty to staff the training sessions for

importance of offering assistance and seeking help four full days; training the faculty using a

(mean=0.39, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.50). ‘train-the-trainer’ approach; securing the physical space

necessary to conduct the simulation training. Other suc-

Evaluation data cesses are reflected in the positive self-report from stu-

At the conclusion of training, participants (n=292) dents and changes in their attitudes, beliefs and

completed a brief evaluation of the experience. Overall, confidence resulting from the training. This may result,

students within each of the three focal areas reported in part, from taking a multimodal approach to case

the trainings to be valuable (1=Not at all valuable, to development that combined manikin simulators with a

5=Highly valuable). They especially reported value in standardised patient or standardised family member.

the TeamSTEPPS introduction (mean=4.57, SD=0.70), This allowed us to capitalise on the benefits of both

and the final debrief following the completion of the modes to provide a rich student learning experience.

three cases (mean=4.29, SD=0.95). The cases were considered realistic and engaging, the

Participants were also asked their level of agreement communication challenges were important, and the

(1=Strongly Disagree, to 5=Strongly Agree) with spe- opportunity to work within interprofessional teams was

cific aspects of the training. Participants were gener- described as valuable. Students enjoyed the activities

ally in agreement that materials were at an and reported they had benefited professionally from

appropriate level (mean=4.42, SD=0.78), provided participation. This benefit was reflected in improved

valuable team skills training (mean=4.66, SD=0.59), attitudes towards interprofessional training, an increased

provided a realistic experience of the challenges faced intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to participate in future

when working in interprofessional teams trainings, a perceived value for the utility of

(mean=4.44, SD=0.78), and provided a valuable TeamSTEPPS communication training, and an increased

opportunity to communicate with students from other sense of perceived self-efficacy in translating the skills

professions (mean=4.71, SD=0.56). learned in training into practice. This was consistent

Students were also asked to describe their most whether students were surveyed on the day of the train-

valuable learning experience in the training. Three ing or 2 weeks following training.

consistent themes emerged: (1) value in the opportun- Our cases, and our case development processes, par-

ity to work with students from different professional allel the recommendations of World Health

schools, (2) the value of learning and practising spe- Organization (WHO)33 for the creation of multiprofes-

cific communication skills in a supportive environ- sional patient safety education. We sought to develop

ment and (3) value of practising skills within an cases that were interesting, relevant, realistic and

interprofessional team. readily applicable to practice. Most importantly, stu-

dents were provided the opportunity to practise skills

DISCUSSION learnt in multiple realistic simulations, and encouraged

The Interprofessional Team Capstone was successful at to engage and receive feedback following each activity.

several levels. Initial successes are reflected in the Students learnt by doing, not simply by observing.

Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 7

Innovations in education

We developed two new instruments for this study This study does not directly address student skill

and reported on a use of the previously unpublished attainment, or the impact of newly learned skills on

AMUSE instrument. These instruments were designed practice. In addition, other researchers have ques-

to allow students to report experiences from interpro- tioned the impact of similar interventions.38 The

fessional team trainings. While observer-based instru- former can be understood to some extent through our

ments for team training exercises have been reported, ongoing analysis of student performance from the

similar self-report instruments have not been widely videos collected during the Capstone exercise. This

discussed. Our instruments may prove of value to will provide some evidence that the skills have been

other interprofessional trainings where educators demonstrated, as well as the quality of the skills per-

seek to better understand student attitudes and formed. Capturing downstream behaviour change,

perceptions. and the impact of this change, are more difficult.

One of the most consistent findings was reflected in Demonstrating the effects of training will require lon-

students’ written stated reports of the value of gitudinal studies to capture the impact of attitudinal

working directly with students from other professions. changes on behaviour within clinical settings.

While most of the participating students had experi-

ence in clinical settings working with practitioners Future directions

from other professional programmes, the majority Simulation training of interprofessional student teams

had minimal experience working in interprofessional represents a first step in establishing improved com-

activities with the people who would be their future munication skills within practising clinical teams. We

colleagues. Fellow students provide an opportunity have shown that student teams can have significant

for learning to occur in lower stakes and a less stress- attitudinal shifts and practice, and observe important

ful environment than working in interprofessional team skills. Our work, funded through the Macy

healthcare teams caring for real patients. Foundation, has allowed us to build distributable

resources, including interprofessional training cases

Limitations and a template model for the creation of new cases.

Our study has important limitations to consider. First, We encourage the development of multimodal simula-

this was a simple pre-post design, without a defined tions employing manikin simulators and standardised

control group. It is possible that student postresponses patients, and standardised family members as a means

resulted, in part, from other aspects of their ongoing to leverage the benefits of both modes while optimis-

professional training. This concern is minimised by ing the student experience. Dissemination and the

the relatively short span of time between the preadmi- application of these materials broadly across health-

nistrations and postadministrations. However, it is care training programmes will demonstrate the

also possible that students were sensitised by the pre- achievement of a principal goal underlying funding.

assessment to be more alert and attuned to the In addition, at the University of Washington, the train-

assessed elements of the team communication train- ings described in this paper have been integrated into

ing. However, few studies meet the rigorous standards the ongoing curriculum.

necessary to draw causal relationships between the Validation of the cases and interprofessional team

various components of training and specific out- training tools will require close inspection and quanti-

comes,34 35 and the empirical base for similar train- tative assessment of the impact such training will

ings has been questioned.36 Future work with ultimately have on the quality of healthcare delivered.

randomised controlled studies of students is needed We do not report unequivocal evidence for the effect-

with outcomes that include later professional practice. iveness of our trainings; we provide a foundation for

We have demonstrated that positive outcomes are team-communication investigators to establish the

obtainable through a short introduction to the next steps to create best-practice training models. Our

TeamSTEPPS skillset, and the opportunity to practise team is currently establishing the validity of observa-

these skills and receive feedback from experienced tional tools to assess team performance, as well as cri-

facilitators. However, interpretation of the findings is teria for the assessment of videotaped team

confounded by unmeasured factors, which include the interactions. The outcomes and successful training

effects of an individual’s assigned team members, and activity reported here, when combined with the obser-

different team facilitators on the team’s learning vational work in development, takes an important

experience. In addition, we have relied on self- step towards meeting the joint commission’s call that

assessment instruments that have not been fully vali- measurement represents the ‘heart of safety,’ and that

dated. This is partly due to the paucity of validated improved care first requires the examination of high-

measurement assessment tools for use with students. quality measures of outcomes.39

This is changing, especially with work around self-

efficacy,37 and we are completing additional validation Acknowledgements The authors would like to

efforts on the tools we have developed for the current acknowledge funding from a Josiah Macy Foundation

study. Board Grant (B08–05), and all the members of the

8 Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952

Innovations in education

University of Washington Macy Team that developed approaches (vol 3: performance and tools). Rockville, MD,

and implemented the cases, simulations and trainings. 2008.

13 McGreevy J, Otten T, Poggi M, et al. The challenge of

Contributors Each author contributed to the conception changing roles and improving surgical care now: crew resource

of the study, the study design, writing and critical management approach. Am Surg [Review]. 2006;72:1082–7;

review of the manuscript. Each author approved the discussion 126-48.

final version of the manuscript. Data collection and 14 Gordon S. Crew resource management. Nurs Inq [Editorial].

analysis was conducted by DB, EAR and CRC. 2006;13:161–2.

15 Powell SM, Hill RK. My copilot is a nurse–using crew resource

Funding The authors would like to acknowledge

management in the OR. Aorn J [Review]. 2006;83:179–80,

funding from a Josiah Macy Foundation Board Grant 83–90, 93–8 passim; quiz 203-6.

(B08-05), and all the members of the University of 16 Sanfey H, McDowell C, Meier AH, et al. Team training for

Washington Macy Team that developed and surgical trainees. Surgeon [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t].

implemented the cases, simulations and trainings. 2011;9(Suppl 1):S32–4.

Competing interests None. 17 Capella J, Smith S, Philp A, et al. Teamwork training improves

the clinical care of trauma patients. J Surg Educ [Comparative

Ethics approval University of Washington Internal Study]. 2010;67:439–43.

Review Board. 18 Weaver SJ, Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, et al. Does teamwork

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; improve performance in the operating room? A multilevel

evaluation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2010;36:133–42.

externally peer reviewed.

19 Mayer CM, Cluff L, Lin WT, et al. Evaluating efforts to

optimize TeamSTEPPS implementation in surgical and

REFERENCES pediatric intensive care units. Jt Comm J Qual Patient saf

1 Joint Commission. Sentinal Events. [cited 20 September 2012]; [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 2011;37:365–74.

http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinelevents/statistics/. 20 Gaba DM. The future vision of simulation in healthcare. Simul

2 Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building Healthc 2007;2:126–35.

a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy 21 Gaba DM. The future vision of simulation in health care. Qual

Press, 2000. Saf Health Care 2004;13(Suppl 1):i2–10.

3 Rogers SO Jr, Gawande AA, Kwaan M, et al. Analysis of 22 Rosen MA, Salas E, Wilson KA, et al. Measuring team

surgical errors in closed malpractice claims at 4 liability performance in simulation-based training: adopting best

insurers. Surgery [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research practices for healthcare. Simul Healthc [Research Support, U.S.

Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 2006;140:25–33. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.].2008;3:33–41.

4 Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the 23 Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess

critical importance of effective teamwork and communication the readiness of health care students for interprofessional

in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13(Suppl 1): learning (RIPLS). Med Educ 1999;33:95–100.

i85–90. 24 Bandura A. The anatomy of stages of change. Am J Health

5 Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, et al. Patterns Promot [Editorial]. 1997;12:8–10.

of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical 25 Bandura A. Self efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W.

patients. J Am Coll Surg [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t H. Freeman and Company, 1997.

Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. 2007;204:533–40. 26 Baker DP, Amodeo AM, Krokos KJ, et al. Assessing teamwork

6 Spath PL, ed. Error reduction in health care: a systems attitudes in healthcare: development of the TeamSTEPPS

approach to improving patient safety. San Francisco: AHA teamwork attitudes questionnaire. Qual Saf Health Care

Press, 1999. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Validation Studies].

7 Kyrkjebo JM, Brattebo G, Smith-Strom H. Improving patient 2010;19:e49.

safety by using interprofessional simulation training in health 27 Leucht R, Madsen M, Taugher M, et al. Assessing professional

professional education. J Interprof Care 2006;20:507–16. perceptions: design and validation of an interdisciplinary

8 Anderson E, Thorpe L, Heney D, et al. Medical students education perception scale. J Allied Health 1990;19:181–91.

benefit from learning about patient safety in an 28 McFadyen AK, Webster VS, Maclaren WM. The test-retest

interprofessional team. Med Educ [Comparative Study Research reliability of a revised version of the Readiness for

Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. 2009;43:542–52. Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS). J Interprof Care

9 DeSilets LD. The institute of medicine’s redesigning continuing 2006;20:633–9.

education in the health professions. J Contin Educ Nurs 29 Reid R, Bruce D, Allstaff K, et al. Validating the Readiness for

2010;41:340–1. Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS) in the postgraduate

10 Guimond ME, Sole ML, Salas E. TeamSTEPPS. Am J Nurs context: are health care professionals ready for IPL? Med Educ

2009;109:66–8. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Validation Studies].

11 Robertson B, Kaplan B, Atallah H, et al. The use of simulation 2006;40:415–22.

and a modified TeamSTEPPS curriculum for medical and 30 McFadyen AK, Webster V, Strachan K, et al. The readiness for

nursing student team training. Simulation in Healthcare: J Soc interprofessional learning scale: a possible more stable

Simulation Healthcare 2010;5:332–7. sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS. J Interprof

12 King HB, Battles J, Baker DP, et al. TeamSTEPPS: team Care 2005;19:595–603.

Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient 31 Bandura A. Guidelines for constructing self-efficacy scales. In:

Safety. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, eds. Pajares F, Urdan T, eds. Self-efficacy, beliefs of adolescents.

Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, 2006:307–37.

Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 9

Innovations in education

32 Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am 36 Eppich W, Howard V, Vozenilek J, et al. Simulation-based team

Psychol [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. training in healthcare. Simul Healthc [Research Support, N.I.

1989;44:1175–84. H., Extramural Review]. 2011;6(Suppl):S14–19.

33 World Health Organization. Patient Safety Curriculum Guide: 37 Mann K, McFetridge-Durdle J, Breau L, et al. Development of

Multi-professional Editional. [cited 14 September 2012 ]; a scale to measure health professions students’ self-efficacy

Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/ beliefs in interprofessional learning. J Interprof Care 2011.

9789241501958_eng.pdf 38 Rosenfield D, Oandasan I, Reeves S. Perceptions versus reality:

34 Lapkin S, Levett-Jones T, Gilligan C. A systematic review of the a qualitative study of students’ expectations and experiences of

effectiveness of interprofessional education in health interprofessional education. Med Educ [Research Support,

professional programs. Nurse Educ Today 2011. Non-U.S. Gov’t]. 2011;45:471–7.

35 Reeves S. An overview of continuing interprofessional 39 Joint Commission. Measurement: the heart of patient safety.

education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2009;29:142–6. Jt Comm Benchmark 2006;8:4–7.

10 Brock D, et al. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2013;0:1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952

View publication stats

You might also like

- Homeschooling PaperDocument13 pagesHomeschooling Paperapi-509508817No ratings yet

- Standard Operating Procedures On Assessment of Staff Training and CompetencyDocument4 pagesStandard Operating Procedures On Assessment of Staff Training and Competencyclairealbertini50% (6)

- Interprofessional Collaboration Three Best Practice Models of Interprofessional EducationDocument11 pagesInterprofessional Collaboration Three Best Practice Models of Interprofessional Educationgenta01100% (1)

- Tableau Developer SeniorDocument10 pagesTableau Developer SeniorSureshAtluriNo ratings yet

- The Mountain of Ignorance (Sunday Adelaja) (Z-Library)Document179 pagesThe Mountain of Ignorance (Sunday Adelaja) (Z-Library)wilfried kassiNo ratings yet

- Tle Laboratory ManualDocument7 pagesTle Laboratory ManualAileene Montenegro83% (18)

- ABB-QA-Test Strategy (9AAD134969)Document38 pagesABB-QA-Test Strategy (9AAD134969)Abhishek Gupta100% (1)

- AITCSArticle InstrumenDocument11 pagesAITCSArticle InstrumenYulianti WulandariNo ratings yet

- Impact of Simulation On Student Attitudes AboutDocument8 pagesImpact of Simulation On Student Attitudes AboutJASMIEN AISYA SASTIARINI AISYA SASTIARININo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Collaboration Three Best Practice Models of Interprofessional EducationDocument11 pagesInterprofessional Collaboration Three Best Practice Models of Interprofessional Educationanzila widyaNo ratings yet

- I Pe Artikel Individ UDocument16 pagesI Pe Artikel Individ UadelllblNo ratings yet

- KeeblerDietzLazzaraetal.2014 TeamSTEPPST TPQCFAValidationDocument11 pagesKeeblerDietzLazzaraetal.2014 TeamSTEPPST TPQCFAValidationHW HYHZNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ReferensiDocument10 pagesJurnal ReferensiBidang KeperawatanNo ratings yet

- CF Exemplar NURS-FPX4020 Assessment 4Document13 pagesCF Exemplar NURS-FPX4020 Assessment 4Sabahat BashirNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 03722Document14 pagesIjerph 19 03722ilhamNo ratings yet

- An Approach To Integrating Interprofessional Education in Collaborative Mental Health CareDocument6 pagesAn Approach To Integrating Interprofessional Education in Collaborative Mental Health Careanas tasyaNo ratings yet

- 1.current Trends in Interprofessional Education of Health Sciences StudentsDocument8 pages1.current Trends in Interprofessional Education of Health Sciences StudentsNguyên NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Sessionsetal High Alert Meds 919 JANDocument15 pagesSessionsetal High Alert Meds 919 JANichabojanNo ratings yet

- Omura 2017Document9 pagesOmura 2017Wijah watiNo ratings yet

- MickenRodger EffectiveTeams Aug2005Document15 pagesMickenRodger EffectiveTeams Aug200504Alya RahmaNo ratings yet

- Nembhard Edmondson - 2006 Making It Safe-The Effects of Leader Inclusiveness PDFDocument26 pagesNembhard Edmondson - 2006 Making It Safe-The Effects of Leader Inclusiveness PDFMd. Shahfayet JinnahNo ratings yet

- Developing Interprofessional Communication SkillsDocument5 pagesDeveloping Interprofessional Communication SkillsWai AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Surviving Workplace Adversity A QualitatDocument9 pagesSurviving Workplace Adversity A QualitatpecescdNo ratings yet

- Health Literacy and Children Recommendations For ADocument8 pagesHealth Literacy and Children Recommendations For ASIRIUS RTNo ratings yet

- Levett-Jones Et Al-2018-Journal of Nursing Scholarship1Document10 pagesLevett-Jones Et Al-2018-Journal of Nursing Scholarship1Nande BandeNo ratings yet

- Rapid Response QualitativeDocument14 pagesRapid Response QualitativeAprilia Putri RahmadhaniNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Teamwork Skills As Predictors of Clinical Outcomes in A Simulated Healthcare SettingDocument6 pagesInterprofessional Teamwork Skills As Predictors of Clinical Outcomes in A Simulated Healthcare SettingNavis NaldoNo ratings yet

- Learning - The Only Way To Improve Health-Care Outcomes: J Deane Waldman and Steven A YourstoneDocument11 pagesLearning - The Only Way To Improve Health-Care Outcomes: J Deane Waldman and Steven A YourstoneAlex GuNo ratings yet

- Sorensen 2018Document36 pagesSorensen 2018munira althukairNo ratings yet

- Measuring Well-Being in A College Campus Setting White PaperDocument52 pagesMeasuring Well-Being in A College Campus Setting White PaperIra LampayanNo ratings yet

- The Critical Need For Nursing Education To Address The Diag - 2021 - Nursing OutDocument8 pagesThe Critical Need For Nursing Education To Address The Diag - 2021 - Nursing OutWakhida PuspitaNo ratings yet

- Quality and Strength of Patient Safety Climate On Medical-Surgical UnitsDocument11 pagesQuality and Strength of Patient Safety Climate On Medical-Surgical UnitsFery AdlansyahNo ratings yet

- Sacks Et Al. - 2015 - Teamwork, Communication and Safety Climate A Systematic Review of Interventions To Improve Surgical CultureDocument11 pagesSacks Et Al. - 2015 - Teamwork, Communication and Safety Climate A Systematic Review of Interventions To Improve Surgical CultureEdy Tahir MattoreangNo ratings yet

- Vogus Sutcliffe 2007 BDocument6 pagesVogus Sutcliffe 2007 BLilymayyuniNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument15 pagesPDFKarine SchmidtNo ratings yet

- Sicometrik ICP IndonesiaDocument10 pagesSicometrik ICP IndonesiaUchi SuhermanNo ratings yet

- Mentorship in An Academic Medical CenterDocument4 pagesMentorship in An Academic Medical CenternoniinnNo ratings yet

- 257.full 2Document9 pages257.full 2Christian N KarisoNo ratings yet

- Reflection Commentary Final Print VersionDocument10 pagesReflection Commentary Final Print VersionHailane BragaNo ratings yet

- Bucknall 2016Document13 pagesBucknall 2016mnazri98No ratings yet

- The Association Between Health Care Staff EngagementDocument10 pagesThe Association Between Health Care Staff Engagementtsa638251No ratings yet

- The Clinical Reasoning Mapping Exercise (CResME) )Document5 pagesThe Clinical Reasoning Mapping Exercise (CResME) )Frederico PóvoaNo ratings yet

- Validation of The Educational Stress Scale For AdoDocument25 pagesValidation of The Educational Stress Scale For AdoHai My NguyenNo ratings yet

- Declaración de Consenso Sobre El Contenido de Los Currículos de Razonamiento Clínico en La Educación Médica de Pregrado 2020 INGLESDocument9 pagesDeclaración de Consenso Sobre El Contenido de Los Currículos de Razonamiento Clínico en La Educación Médica de Pregrado 2020 INGLESjaldoquiNo ratings yet

- How To Be A Very Safe Maternity Unit An Ethnograp - 2019 - Social Science - MedDocument9 pagesHow To Be A Very Safe Maternity Unit An Ethnograp - 2019 - Social Science - MedAkinsola Samuel TundeNo ratings yet

- 1 - Mousa (2021) - Woman Leadership in HealthcareDocument11 pages1 - Mousa (2021) - Woman Leadership in Healthcaregundah noor cahyoNo ratings yet

- A Thesis (Proposal) Presented To The Faculty of The College of Nursing Adamson UniversityDocument22 pagesA Thesis (Proposal) Presented To The Faculty of The College of Nursing Adamson UniversityRaidis PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Overview: Evidence-Based Strategies For Occupational Health Nursing PracticeDocument9 pagesHealth Promotion Overview: Evidence-Based Strategies For Occupational Health Nursing PracticeAdrîîana FdEzNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Awareness On Occupational Safety andDocument10 pagesAssessing The Awareness On Occupational Safety andmariel orbetaNo ratings yet

- Academic-Clinical Service Partnerships Are Innovative Strategies To Advance Patient Safety Competence and Leadership in Prelicensure Nursing StudentsDocument5 pagesAcademic-Clinical Service Partnerships Are Innovative Strategies To Advance Patient Safety Competence and Leadership in Prelicensure Nursing StudentsYiyiz HertikaNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisDocument14 pagesPerceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- AssessmentDocument9 pagesAssessmentdian maya puspitaNo ratings yet

- Safer Coalmines, Happier, Healthier and More Engaged CanariesDocument3 pagesSafer Coalmines, Happier, Healthier and More Engaged CanariesahmedsobhNo ratings yet

- Collegian: Michelle Barakat-Johnson, Michelle Lai, Timothy Wand, Kathryn WhiteDocument8 pagesCollegian: Michelle Barakat-Johnson, Michelle Lai, Timothy Wand, Kathryn WhiteSUCHETA DASNo ratings yet

- Ginsburg 2010Document26 pagesGinsburg 2010ReginaPutriAprizaNo ratings yet

- Asian Nursing ResearchDocument7 pagesAsian Nursing ResearchWayan Dyego SatyawanNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness in The OR A Pilot Study Investigating The Effi - 2021 - JournalDocument12 pagesMindfulness in The OR A Pilot Study Investigating The Effi - 2021 - JournalLuz GarciaNo ratings yet

- 2019 - Lee & Quinn - A Lit ReviewDocument7 pages2019 - Lee & Quinn - A Lit ReviewazeemathmariyamNo ratings yet

- Text Analysis ReportDocument5 pagesText Analysis ReportElvis Rodgers DenisNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument11 pagesContent ServerMona AL-FaifiNo ratings yet

- Develop Med Child Neuro - 2021 - Ogourtsova - Patient Engagement in An Online Coaching Intervention For Parents of ChildrenDocument8 pagesDevelop Med Child Neuro - 2021 - Ogourtsova - Patient Engagement in An Online Coaching Intervention For Parents of ChildrenpsicoterapiavaldiviaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: Kelly J. Morrow, Allison M. Gustavson, Jacqueline JonesDocument10 pagesInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Kelly J. Morrow, Allison M. Gustavson, Jacqueline JonesFirman Suryadi RahmanNo ratings yet

- Faculty Development CPDDocument6 pagesFaculty Development CPDAida TantriNo ratings yet

- Effect of Transformational Leadership On Job Satisfaction An - 2018 - Nursing OuDocument10 pagesEffect of Transformational Leadership On Job Satisfaction An - 2018 - Nursing OuJuan Jesús F. Valera MariscalNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion in Medical Education Lessons From A Major Undergraduate Curriculum ImplementationDocument10 pagesHealth Promotion in Medical Education Lessons From A Major Undergraduate Curriculum ImplementationKAREN VANESSA MUÑOZ CHAMORRONo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mastery Learning in Health Professions EducationFrom EverandComprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mastery Learning in Health Professions EducationNo ratings yet

- Nlit1 1609Document8 pagesNlit1 1609fransiskus mekuNo ratings yet

- Interprofessional Education (Ipe) Improves Students' Communication Skills: A Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesInterprofessional Education (Ipe) Improves Students' Communication Skills: A Literature Reviewfransiskus mekuNo ratings yet

- Kelompok 4Document11 pagesKelompok 4fransiskus mekuNo ratings yet

- Kelompok 3Document9 pagesKelompok 3fransiskus mekuNo ratings yet

- Ethical NursingDocument13 pagesEthical Nursingfransiskus mekuNo ratings yet

- Konflik Kepentingan Di PPDBDocument13 pagesKonflik Kepentingan Di PPDBMOCHAMMAD HABIB SAPUTRANo ratings yet

- Foreign Stud and Local Lit RechelDocument1 pageForeign Stud and Local Lit RechelMeane BalbontinNo ratings yet

- New Approaches To Managing StressDocument5 pagesNew Approaches To Managing Stresssmith.kevin1420344No ratings yet

- LP Educ70Document9 pagesLP Educ70Romina DaquelNo ratings yet

- Social Entrepreneur Mr. Rajendra JoshiDocument9 pagesSocial Entrepreneur Mr. Rajendra JoshiChintan DesaiNo ratings yet

- Activity No. 1Document1 pageActivity No. 1Rolando Lima Jr.No ratings yet

- Information Sheet 3.2-1 - Cultural AwarenessDocument13 pagesInformation Sheet 3.2-1 - Cultural AwarenessWyattbh AaronwyattNo ratings yet

- 2018 CPD CFlyer 3Document3 pages2018 CPD CFlyer 3zolalkkNo ratings yet

- Electrical and Computer Engineering CatalogDocument9 pagesElectrical and Computer Engineering CatalogNadisanka RupasingheNo ratings yet

- Cambryn: RubinDocument1 pageCambryn: Rubinapi-451265252No ratings yet

- Post Event Report WritingDocument6 pagesPost Event Report WritingMansi PatelNo ratings yet

- WHLP-March 5!Grade-7-Q2-W7-8Document4 pagesWHLP-March 5!Grade-7-Q2-W7-8Caryl Ann C. SernadillaNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus For The Course Psychological TestingDocument3 pagesCourse Syllabus For The Course Psychological TestingFrehiwot AleneNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of 2 Disinterested Person Stating DiscrifancyDocument1 pageAffidavit of 2 Disinterested Person Stating DiscrifancyRich RazonNo ratings yet

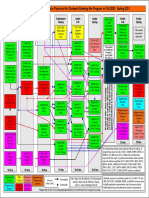

- Mechanicalengineering Sequence Chartfor Fall 2020 To Spring 2021Document1 pageMechanicalengineering Sequence Chartfor Fall 2020 To Spring 2021RonaldNo ratings yet

- PPGDocument5 pagesPPGapi-253644880No ratings yet

- Lucerne Festival AcademyDocument6 pagesLucerne Festival AcademyEduardo SantosNo ratings yet

- Articles: Self-Improvement Tips Based On Proven Scientific ResearchDocument3 pagesArticles: Self-Improvement Tips Based On Proven Scientific ResearchMike ReyesNo ratings yet

- The Role of Pragmatics in Second Language Teaching PDFDocument63 pagesThe Role of Pragmatics in Second Language Teaching PDFAndreaMaeBaltazarNo ratings yet

- Fisrt Quarter Exam For English 8Document5 pagesFisrt Quarter Exam For English 8Kathleen Legaspi MartinezNo ratings yet

- Your Personal: Masterclass WorkbookDocument10 pagesYour Personal: Masterclass WorkbookRohit RoyNo ratings yet

- Exam 2º Bachillerato.Document2 pagesExam 2º Bachillerato.Bautista Ramos SaíñasNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Essay of PlaceDocument2 pagesDescriptive Essay of PlacedinnielNo ratings yet

- Open House Checklist 18-19Document1 pageOpen House Checklist 18-19api-467926588No ratings yet