Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rediscovering Early Non-Fiction Film

Rediscovering Early Non-Fiction Film

Uploaded by

Manuela MorarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rediscovering Early Non-Fiction Film

Rediscovering Early Non-Fiction Film

Uploaded by

Manuela MorarCopyright:

Available Formats

Rediscovering Early Non-Fiction Film

Author(s): Stephen Bottomore

Source: Film History, Vol. 13, No. 2, Non-Fiction Film (2001), pp. 160-173

Published by: Indiana University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3815423 .

Accessed: 15/06/2014 00:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FilmHistory,Volume 13, pp. 160-173, 2001. Copyright? John Libbey

ISSN:0892-2160. Printedin Malaysia

Rediscovering

early

non-fiction film

StephenBottomore

In recent years a rediscovery of early non-fiction archivists.2 But I suggest that a more deep seated

film has been taking place. I have always been reason for the eclipse of the factual film is the influ-

an enthusiast for these first 'documentaries', so ence of a particularmodel of film history.

in principle I should welcome an airing for more That model might be summed up in the title of

of these rarely seen films. Yet I have a number of RudolfArnheim'sbest knownbook, TheFilmAs Art

misgivings about how such films have been exhibited of 1932.3 This phrase has been the often unspoken

since the 1990s. It seems to me that some of the assumption underlying most forms of film study

screenings have been planned and executed with since the 1930s - that at its best cinema can be an

littlereference to the context in which such films were art form, and indeed that it is probably only worth

originally shown in the years when they were made. studying and writing about if that is the case. Most

Early non-fiction has been programmed in these writers on film from the 1930s onwards have been

modern 'retrospectives' much as fiction films from a largely concerned with fiction film, but this desire to

later era are programmed, despite being a very uncover the 'art of film' has also filtered into docu-

different filmic genre. While I applaud the intention in mentary studies. Paul Rotha's best known film book,

trying to bring some of these films before a modern TheFilmTillNow certainlyfollowedthis 'art'agenda,

audience, I have some suggestions about how the and his book, DocumentaryFilmof 1936, carried

films might be programmed more sensitively in the over his concern with film as art into the non-fiction

future. realm. In particular he made a claim for the origins

of the documentary film:

Beyond the documentary as art

... documentary may be said to have had its

For many years the early non-fiction film has been

real beginnings with Flaherty's Nanook in

sadly neglected by film historians. This type of film

America (1920), Dziga Vertov's experiments in

was largely ignored during the first period of reawak-

Russia (round about 1923), Cavalcanti's Rien

ened interest in early cinema, exemplified by the

Que les Heures in France(1926), Ruttmann's

Brighton conference in 1978, which covered only

Berlinin Germany(1927) and Grierson'sDrift-

early fiction films.1 Even as late as 1995 at pre-

ers in Britain(1929).4

screenings for the Domitor (early film association)

conference, out of 139 films shown, only five or six I submit that this model has dominated most

were non-fiction. discussion and writing about non-fiction film up to

There are several reasons for this long-stand- the present day, notably by implying that the docu-

ing neglect of early and silent non-fiction, the first mentary is art or it is nothing; and, essentially derived

being simply that historically the fiction film has from this, that no 'real' documentaries were made

enjoyed greater popularity than its factual brother. before 1920. According to Rotha's view, certain non-

Another reason is lack of basic research: even quite

accessible sources such as trade journals are rela-

tively rarely consulted for information on non-fiction Stephen Buttomoreis a documentaryproducerand

an independent film historianspecialising in early

films and filmmakers, while one of the best secon- cinema.Correspondenceto: 27 RoderickRoad,Lon-

dary sources, Krows' 'Motionpictures - not for thea- don NW32NN, UK.

tres', is scarcely known by most film historians and [E-mail:sbottomore@dial.pipex.com]

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscoveeria_l^1

W,

161

. . .

.

fiction films, beginning with Nanook were accounted

'real'documentaries, while others, even though they

,lhe trues' and mosi oApict'ure wilh more drama, greater

might have come before, were not. Thus, all the human story of thb thri, and stronger ae/ion than

travelogues, industrial, interest, advertising, scien- qreal While Snows any picture you eversaw.

tific, and other films made from the 1890s were

suddenly consigned to the outer darkness, for Rotha

only considered films which had a certain 'personal'

vision to be real documentaries.

This has contributed to a skewing in scholarly

work on the history of documentaries, with far more

interest in the exceptional productions, major 'art'

documentaries, fiction/non-fiction hybrids, etc, and

less interest in the workaday travelogues, industrial

and advertising films.5 Look at the best known pub-

lished books on documentary, such as those by

Barsam and Barnouw, and the compilations edited

by Rosenthal and MacDonald.6 Most of these not

only skate over the early period, but in their main

coverage from the 1930s onwards they very much

focus on the exceptional films of the non-fiction

genres: those that were noticed, that caused contro-

versy, that were made by major film-makers. There

is little coverage in these sources of the typical

non-fiction film. The vast majorityof workaday trave-

logues, industrial, interest films are virtuallyignored,

as are their modern counterparts: average television REVILLON

FRERES

PAESEENT

."Y

documentaries. Even Charles Musser, who has done

so much to rehabilitate early non-fiction cinema, in

his well-crafted essay on silent non-fiction makes no

reference, for example, to mainstream industrialfilm-

making, even though this was a major sector of film

production by the teen years.7

This is not a criticism of these authors, for they

deliberately set out to signal the highlights of the A STORYOF LIFEAND LOVEIN THEACTUALARCTIC

history of non-fiction, the 'remarkable' films of the OROBT

J. F TY

ROBERT J. FLAHERTY. F.P.G.S.

F

Pafhenlicure

periods they cover. Fine collections like Rosenthal's

_- =- =

deal with some of the most noticed films, and most :. -,::::. X.:;:::::: . ..... .........?';;'::::.:

I

.<:.

.

..........:;. . "~

',t:.: :: <iy::iFF:i

controversial issues in documentary. But Iam simply

arguing that additional work needs to be done: in some parallel in the study of the fiction film. Foryears Fig. 1. Nanook

studying the non-fiction film in general, and estab- the most common way to study feature film produc- oftheNorth

lishing some more statistical data on the genre and tion was through auteur theory, looking at the great (Robert Flaherty,

its historical development. The problem is that a creators of the cinema and little else. Dozens of 1920)- thefirst

'real'

conventional 'canon' has been established which major studies appeared about particular directors, documentary?

only takes in a few high points, including the Lu- such as Hawks and Hitchcock, Eisenstein and

mieres, Nanook of the North, the Kino-Eye school, Renoir. Variations of auteur theory add in the other

Drifters,etc (the old familiar list), while more run-of- creative talents in filmmaking, and so an equivalent

the-mill non-fiction films have been ignored. In this avalanche of people-focused books have appeared

way film history has only seen the tip of the iceberg (and continue to appear) on stars, screenwriters,

of non-fiction, while much that lies beneath the sur- even cameramen and make-up artists. And just as

face has been overlooked. with the current focus in documentary studies on

This focus on documentary 'highlights' has certain outstanding films, this approach to fiction

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

162 Stephen Bottomore

filmmakingconcentratedon certaingreat films,the rediscoveringearlynon-fictionfilm(as well as early

CitizenKanes and Birthof a Nations of the filmic film in general), and I feel a vibrantdiscussion of

firmament. these issues can do nothingbut good.

Itwas onlyinthe 1970s thata more'historically

neutral'approachsaw the lightof day, withthe use Collecting versus programming

of statisticalstyle analysis by BarrySalt, and the Inmost projectsto exhibitcreatedwork- whetherin

meticulousworkof TheClassicalHollywoodCinema. an art gallery, a cinema, or anywhereelse - the

The latterin particularwent beyond the 'greatman' questionof choice is the primaryone: 'whichworks

school of Hollywoodhistory,and for the firsttime should one put on display?' In art exhibitionsthe

took a randomlyselected group of Hollywoodfilms primarycriterionof selection is often 'who created

and analysedallkindsof variablesincludinglighting, the works?','who was the artist?'On this basis we

editing, and story themes. In this way one could might have an exhibitionof Rembrandt'spaintings

appreciate how the Hollywoodsystem manufac- orHenryMoore'ssculptures.Thisartist-basedselec-

tured movies, in many ways this system acting as tion is used partlybecause there may be few other

more of an auteurthanthe individualhumanbeings obvious ways to group the works,and because we

who workedon particular films.(Andallthiswas not, consider that one particularcreative individual

obviously,to deny that certainfilms rise above the played a more importantrole than others. So for

plainof the typical,northatthereare worksof cine- example, while it is perfectlyreasonableto present

maticgenius). an exhibitionof Rembrandt'spaintings,it mightbe

As faras non-fictiongoes, whilethis statistical considered somewhat perverseto present a selec-

approach has not yet appeared, historianshave tion of them based on who made the frames that

startedto overturnRotha'srigidideas on whatwere enclose the paintings.

the firstdocumentaries,and have begun to examine Whileselection based on the artistis probably

some of the earliernon-fictionfilms in the world's the most common way of organisingan artexhibi-

archives.8The high water markin the 'rediscovery' tion, it is not the only one. Another reasonable

of early non-fictionwas the mid-1990s.The theme methodmightbe to choose paintingsof a particular

was initiatedwhen the NederlandsFilmmuseumor- historicalperiod or with a particulartheme, e.g.

ganised a workshopon silent non-fictionin 1994. 'Modernism'or 'war'.Inall cases the ultimateaim is

Then the following year Bologna's 'Cinema to select a series of workswithsomething in com-

Ritrovato' organiseda programmeentitled'11 non-fic- mon.

tion dal 1900 al 1914', and in the same festival This notion of 'collectingthe similar'has its

screened several silentfilmsof expeditions.InSep- analogue inthe worldof cinemainthe 'retrospective'

tember 1995 the Haus des Dokumentarfilmsin or 'season'. This involves collecting together and

Stuttgartalso mounted an event concerned with screeningina 'season' severalexamplesof the work

silent non-fiction.9And in the autumnof 1995 the director('auteur'),star,writerorstudio.

of a particular

Pordenone festival ran a major non-fictionpro- This approach has also been used for screening

gramme.These events have allowedlargenumbers early films at festival venues such as Bologna or

of the survivingcorpus of these early films to be Pordenone:a numberof filmswithsome connection

seen, so givingfilmhistoriansa cleareridea of what - such as comingfromthe same studioor the same

typicalearlynon-fictionfilmswere like,and starting country- are screened as a group, to (as it were)

to move us beyond the Rotha-esquecanon of great showcase the 'artisticcorpus'. Thiswas also to be

documentaries. the approach taken in presenting the non-fiction

However, I submit that aspects of Rotha's programmes shown at the Pordenone festival in

ideas on 'documentaryas art'havecontinuedto hold 1995.

sway,especiallyininfluencingthe informational con- Pordenone's non-fictionyear was by any

text in whichthese filmsare screened, and in deter- standards a majorshowcase for early non-fiction,

mining how they are grouped and programmed withhoursworthof filmsbeing shownoverthe week.

together.10InwhatfollowsImakesome suggestions Myownreactionwas that,whileIwas gratefulto have

about where I feel recent screenings of non-fiction such a chance to view earlynon-fictionfilms,some-

films have gone wrong. No doubt many people will thingwas wrong.Thefailure,in myview,was simply

disagree; I hope they willnot take offence. We are thatthisstandardprogrammingmodelof the 'collec-

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscoverin earl non-fiction film 163

tion'or'retrospective' didn'twork.The'retrospective' TYKE ~~~~~~~~THIS

WEEK,NEXTWEEK,

system makes considerablesense as faras screen- FILM RELEASES.

FDILM

RELEASES. AFTER.

AND THE WEEK

(June 16th to July 7th.)

ing fictionfilms fromthe feature period,where the

ABBraVIATIONS: B r, BuriesrIn; C Corn, Comic; ?, Drama; Educa

Comedy;, Des, Descriptive; E,

tliona; F, Fantasy; G, Gymastc; H, Hitorical; Int, I,Industrial;

Melodrama; Interest; M, NH Natural

Hstory; P, Pathetic; R, Romance; S, Scenic; Sn Scientific; Spec, Spectacular; Sp, Sporting; T, Travel, Tr, Trick;

films are shown singly over a period of days or Ambrosio,

Top, Topical.

Biograph,

weeks. Itworks because each long filmis more or See Agency, 83, Shattesbury Avenue, W.

Oerrarad un. ltuaelms, London.

Den. Feet. 'Date.

M.P. Sales Agency, 86, WardonurStreet, W.

City 64n Bloselig, London.

less a programmein itself,and a modernscreening Friscot's Now Occupation................Comrn 475 June 16

Alonigthe Simplon Road........................T 380 - 20 Help! help:.........................................C

De. Feet. Date

498 June

ProaperityFeunced on Anot-her'sRuin..- 1253 - 23 The Female of the Species..................... 99 -

is largelyreproducingwhat audiences of the time Tweedledum'a Sweet Wife.................Comrn 546 - 23

Festivals in India...............................Int 490 - 27

Just Like a Woman ............................D

The Restoration........................... D

98 - 20

64 -

16

A Hcneymoon Journey........................CD 1203 - 27

wouldhave seen. Tweedledum Income .......................Corn 673 - 30

What's Your Hurry?.........

One is Buaine, the Other Crime....

403 -

998 - 23

0

Ih I were a King ....:..............................D 574 July4 Won By a Fish......... ...........................C 633 - 23

ButIwouldargue thatthis 'collection'system The Ship............................................D

Harried Lovers

Married Levere.............................

...................................C

1647 -

.C 65605 --

7

77

The Brave Hunter

h Leaner

The' ^r Evil....................................D

r r r :::D

C 466 - 27

1009

10 - 30

5

is ofteninappropriate forthe one-reelera, especially American

Film Cempany,

Tyler Hcene.t

Standard,

Limited, Film W

The Fickle Spaniard.............................C

The Light that Came............................D

456 - 30

998 July 4

C,ereardw

TFCRm.

('

997,e,-md imeL, The Old Actor......................................D 1020 - 4

fornon-fiction,because itmeans showingseveralof Love Will Find a Way...........................C~~TyAtm.ALedr4.

Let Us Be Divorced..............................C

1060 June 16

916 - 20

A Lodging for the Night.......................D

A Midnight Adventure..........................C

1018 -

633 -

7

7

the same type of filmone afterthe otherinthe same Mamie Bolton ......................................C

Do Your Duty.. .................................

965 - 0

905 July 78. Crtng C

Cine,

Rod, W.C.

sitting,whichwouldneverhave been practisedat the il West,p,

American Wild conica im. Ro.eicine, Londo.

Ame.

icnie

(G. M~Iles, N WYel

N.Y.) Poor George.........................................C 1000 June 19

J. P. Brocklilu,.4., New Compton Street, W.C. Mr. Stout's Adventures.....................Comrn 833 - 19

timethe filmswere made. Gatheringtogetherseveral Gerrardiet.

Her Spoiled Boy.................. ................D

ntanilm.l,oinedn.

1015 June 15

Tontolini's Quid................................Com

Bibbie's Revenge..................................D

449 - 22

1017 - 22

Great Heart of the West........................ D 1000 - 22 Siena and Vicovaro...............................T 478 - 22

short films (and in the early teen years most films Cowboyversus Tenderfoot..... ................D

The Spur of Necessity........................... D 1000 July 6

1006 - 2 The Debt Paid.....................................D

Saved .................................................D

1656 - 26

1587 - 29

were under15 minutesduration)by the same maker B. and C.

M.P. Sales Agncy, 98, Wardenr Street, W.

Eclipse of the Sun.................................E

Reunited ............................................D

285 - 29

921 - 29

The Police Sergeant..............................D 1295 July 3

or studio,whileusefulforhistoriansand academics, City Au& Bloeelig.

BattalioenShot......................................D

Two Bachelor Girls..............................R

Lt.don.

890 June

900

16 Mona Lisa with a Moustache.................C

Dolly's Savings .....................................D

633 -

630 -

3

6

20

is often profoundlydullforthe viewer.Particularly so Smuggler's Daughter of Anglesey ........D 1090 -

The lheAdventre

Pedlar ofo Penmaenmawr.................D

Senarie D 860 -

86

23 l',,'ssio Play in Southern Italy............Int

The Wrong Hat................................Com

670 -

670 -

6

6

The Adventuires PekT

upn:

of Dick Turpin: ..........,Series

I., The Fox Hunt.......................................C 436 - 6

in the case of non-fiction. The King of Highwaymen............D 1132 July 7

12. Charing Crn

Clarendon,

Broncho. Road. W.C.

At each screening in Pordenoneseveral non- Western Import Co., Ltd., 7, Rupert

WsrIptC,Streetd,

W. SueredtMind

Court, Rupert entre7H20.

the Paint................................Com

ClariGfim,Ltnd6n.

475 June 16

.iorr,rd 8000. . Weqlm, Sharp Practice................... ................. D 838 - 23

oStreet.

fictionfilmswere shown one afterthe other,mainly For a Western Girl.............................. D1' 539 June

Ikey Mo's Dream............... ..............Corn 410 -

19 Mr. Diddlem's Will.............................C

22 Sheepskin Trousers; or, Not in Theao...Bur 720 July 7

375 -

in the minorof two venues of the festival.The vast Young Deer's Return...........................D

Mr. Deooley'sHoliday........................Co

588 - 26Crick

KinemaographOne.

& Martin,

l, Wrdo Street W

The Red Men's Bravery.........................D 556 July 6 ityoerae. Biloeeq, Londone.

numberof films that were shown overallseemed, Film

Cosmopolitan,

QGrrardStreet, W.

Cold Steel............................................D

How Smiler ' Raised the Wind .........Corn

825 June 20

750 - 22

llHns,

paradoxically,to suggest some lack of confidence Gerrardn8M.

What the Window Cleaner Saw.............-

'he Curse of Avarice...........................-

540 June

1000 -

Constable Smith in Command............Tr C 440 - 27

16 The Farmer's Daughter........................ D 975 - 29

16 Muggins, V.C.................................. .... 865 July 4

in the entire enterprise,as if it were a desperate Syracuse .............................................T

His Besetting Sin............... .................D

395 -

1000' -

20 On an English Farm...........................Int

20Empire,

345 - 6

The'Race of Mountain Climbers.........Comrn 450 - 23 t P Siles Agency86, Wrdur Street, W.

attemptto get the unwelcomecreatureof non-fiction Blazing the Trail.................................D

The Test of Truth.................................D

2100 -

1000 -

23 City 48.

27 Views in Durban...................................T

Bi-sellg,l,ondn.

260 June 16

entirelydone and out of the way with in that single The Making of a Soldier........................E

Feeding Time......................................

375 -

F 275 -

27 Father's Forty Winks3.......................

30 Making Gelf Clubs...............................1

330

330 - 30

The Clown ..........................................D 1250 - 0 Among.the Ferns and Waterfalls of the Blue

year. And this was indeed to prove the case, for The Crisis .......................................... 2,000 July 7 tountains, N.S Wales T 245 July

non-fictionas such has never raised its uglyface at

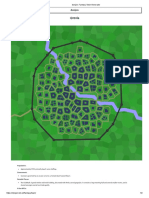

Pordenoneagain, and Isuspect thatthisexperiment Fig.2. (above)

Sometradejournalslisted

was seen as a failureby the festivalorganisers.But newfilmreleases

withanabbreviationnext

I suggest that the failurewas in the programming whattypeoffilmitwas.

toeachtoindicate

model, ratherthan in the films, for this 'collecting' (Incidentally aninteresting

giving insight

aesthetic goes rightagainst the grainof how such intothoughts genreinthisera).

about

[The 20June1912.]

Bioscope

filmswere originallymeantto be presented.

The pointis thatearlycinemagoers neversaw

a collectionof similarfilms screened together;they

almost always saw a mixedprogramme.Even into

the 1920s a programmewas the norm-'an eve-

ning's entertainment',to quote the title of Richard

Koszarski'sbook on Hollywood'ssilentfeatureera.

Inessence thiswas the movietheatre'sequivalentof

the varietyformat.Inthe earlyperioda programme

of a half a dozen to a dozen short films was the

I '

standardexhibitionformat- a mixof everythingfrom

dramasand comedies to traveloguesand news. The

trade press, in listingfilmsavailablefor purchaseor

FIRST

BEST.

ted

\ Fig.3. (left)Boards

displayedoutside

likethiswere

cinemastoshowthe

rentalwouldoften indicatethe genre of each film,so The Original Cinema Letter Combination. orderoffilmsintheprogramme (and

the exhibitoror rentercould put together a mixed NEATEST and CHEAPEST sometimes, ashere,toindicate

the'genre'

Programme Outfit. ofeachfilmtoo).Thetitleofeachfilmwas

programmewithoutactuallyseeing each film. IMITATEDbut UNAPPROACHED in ona slat,which wasslotted

intotheboard.

Findingout what was includedin typicalcin- EFFECT, DURABILITY

and PRICE.

[TheBioscope 19March 1914.]

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

164 Stephen Bottomore

ema programmesfromthe pre WorldWarOne era by a travelogue.(Westdidn'tmentionnewsreels,but

is notquiteas easy as one mightsuppose. Relatively these were also frequentlypartof the programme).

few were listed in trade journals,for the very good Some exhibitorsalso realisedthat differenttypes of

reason thatthe programmewas often decided and filmshad differingemotionaleffectson the audience,

compiled by the local showmanfor his one cinema and interweavingthe diversityof genres helped to

alone, or sometimes it came fromthe local renter, regulatethe pace of the exhibition.Thiswas partof

readycompiled.Butprogrammelistingsmaysome- the significanceof non-fictionwithinthe programme

times be seen in survivingprintedprogrammesand (See Appendix).

in theatreadvertisementsin local newspapers. Pro- Despite the 'rediscovery'of silent cinema in

grammes of filmsmay also be seen in some surviv- recentyears, the newlyfoundfilmshave rarelybeen

ing photographs of the fronts of picture palaces, presentedinsuch a mixedprogrammeformatat any

where a list of filmsto be shown was advertisedon of the silent filmvenues. The strategy has almost

a special slatted programmeboard near the en- invariablybeen to show a collectionof filmsby one

trance.Hereis a sample programmeof filmsfroma person or productioncompany,and this approach,

Britishpicturepalace in 1910: while satisfying academic rigour, I would argue

sometimes results in tediumfor the viewer.This is

TheHonorof his Family(Biographdrama)

ChurchParade(factual) especiallytrueof non-fiction,for,withsome excep-

Military

tions, non-fictionfilmshave alwaysbeen supporting

WinterSports,Copenhagen(travelogue)

films, not main attractions.They either helped to

Accompaniedon the Tom Tom ('a rollicking

make up a programmein whichfictionwas the key

Englishscreamer',i.e. comedy)

attraction,orwere used in non-theatricalcontextsas

Wanteda Mummy('refinedhumour')

educational,commercialor promotionaltools. Totry

Sorry,Can'tStop ('excitingcomic') to runa complete programmeof non-fictionwould

TheEgyptianMaid('magnificentcoloured

have been consideredan act of sheer follyby most

production') exhibitorsof the silentera.

Daughter of the Sioux ('sensational Indian

Equally,though, to runa programmewithout

picture')11

any non-fictioncomponent- such as newsreels or

Note the mixof comedies and drama,along travelogues- would have been almost equallyun-

withtwo non-fictiontitlesamong the totalof 8 films. usual.Inthissense myargumentcuts bothways, for

The arrangementand make-upof the programme an all fictionprogrammecan be just as tedious as

changed over the years: for example, a cinema in an all non-fictionone. Certainlyviewersin the silent

Poplarin 1907 offereda greaternumber(of shorter) periodwouldneverhave sat throughfive Eclairdra-

films than the example above, and also a greater mas on the trot,as Pordenoneviewerswere invited

proportionof non-fiction- 7 or 8 titles out of 18 in to do duringanotheryearof the festival.Isubmitthat

all.12Allprogrammesfromthis era that I have seen this screening philosophybased on 'collectingthe

entaila similarmixingof genres, withnon-fictionfilms similar'is unfairto these films, and weakens their

almost always included. Cinema managers in the impactthroughbeingpresentedina contextthatwas

early period understood how this mixed program- neverintended.

mingformatworked,and certainlyknewthatmaking Whilethere have been few ifany programme-

up a programmeof all the same type of filmswas based screenings of early films in recent years in

not a good idea. A well knownearly exhibitor,T.J. festivals or conferences, one rare and interesting

West, noted in 1914: experimentalong these lines has been takingplace

at the NFTVAfor the past several years (and con-

As faras the 'makeup'of an idealprogramme

cluded in 2000). Everymontha dozen or so viewing

is concerned, the best possible selection of

copies of Britishfilmsmade before1915 wereshown

pictures for an average audience is, to my in an Archiveviewingtheatre.They were selected

mind,one which has varietyas its keynote.It

should include dramas, comedies, scenic, alphabetically,each monthprogressingthroughthe

alphabet. Thus one monthwe would see all titles

educationaland scientificsubjects.13

betweenABoldVenture(Hepworth,1912)and British

Insuch a programmea comedy would alter- Columbia:Loggingin Winter(Urban,1908) and the

natewithan educational,a dramamightbe followed next monthall titles between a BritishDentalAsso-

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscovering early non-fiction film 165

ciation instructionalfilm and a Lewin Fitzhamon categories firmlyseparated. Such viewerscome to

comedy of 1907, The Busy Man. Inthis accidental Pordenoneor othervenues preciselybecause they

way a mixed 'programme'of fictionand non-fiction want to see, for example, all of Griffith's1909 films

was created, which was as similar to the pro- in one place and at one time,allowingthemto chart

grammes of films of the pre-featureperiod as any a director'sdevelopmentover time. These festival-

screenings in recentyears. Forthe viewerthe result goers do not care that it is not an 'authentic'experi-

was an entertainingmix, in which every taste was ence, and they do not necessarily experience the

catered for, and no-one had time to get bored with tediumthataudiences of the timewouldhave felt in

any one type of film. seeing reams of similarfilms. They are there as

I suspect that in coming years there will be historians,and collectorsof information.

increasing interest in this 'authentic'style of pro- No doubttheywouldarguethatthe 'collection'

gramming.Atthe Amsterdamworkshopon 'colonial formatplays a similarpartin filmhistoryas the art

cinema' in 1998, whilethe conventional,retrospec- gallerydoes in painting.Inan artgallery,the pictures

tive programmingformatwas used - withblocks of are usuallyarrangedby period, school and artist.

similarfilms being shown - an alternativewas pro- Few exhibitionorganiserswouldsuggest thata vari-

posed at the very end of the event by historian ety formatwouldbe appropriatefor paintings,with,

NicholasHiley,who suggested thatthe originalpro- for example, a Warholsharing wallspace with a

gramme model that I have described might have Vermeerand a Turner.Likeshould be placed with

some appeal as a way of showing earlynon-fiction like, they would say, to allow the galleryvisitorto

to modernviewers: study severalworksby a particularartistor school.

On the other hand the essential difference

I thinkthatthis questionof how can we show

betweenartin a galleryand filmsin a cinema is that

these images to generalcinema audiences is

one can go at one's own pace in a gallery,studying

an enormously importantone. It's also an

particularpicturesat leisureforsome time,while'fast

enormouslydifficultone... Itmightbe neces-

forwarding'throughanotherdullertwenty pictures

saryto go backto the solutionthattheyfound,

witha quicklook roundand a swiftwalkto the next

which was to put these pieces of film into a

galleryspace. But no Pordenoneattendee has yet

programmethat was predominantlya fiction

suggested to my knowledge that the relentlessly

programme.Andalthoughyou can use these

calculated16 or20 framepersecond rateforscreen-

films in researchcontexts, to make particular

historicalpoints, I think it's worth thinking ing silentfilms should be upped to 'fastforward'in

the case of unusuallytedious reels.

about feeding them back into the main pro-

Perhapsa moreappropriatecomparisonto be

grammeof exhibition.Infact,some of the most

made withscreening a filmwould be another'real-

interestinguses I'veseen of old newsreels is time'artform:music. As concerthalldirectorshave

to put itback intothe cinema programmewith

knownforgenerations,a concerthas to be carefully

filmsof the same date. Letthe audience see

that there were differentways of filmmaking, programmedto attractand hold an audience. The

most popularprogrammewouldprobablycombine

differentmodes of address, and styles of pres-

a varietyof differentstyles and composers. So if a

entationat the same time as that majorfilm

venue put on a concert consisting exclusivelyof

that they've gone to see. Itwas always said

Kreutzer'ssonatas, or nothingbut Mozart'sallegro

that the newsreelwas somethingyou got for

free when you paid to see the mainfeature.It movements,fewwouldexpectaudiencesto be lining

the streets to attend such exercises in academic

may be that you have to start programming

this material,using thatsame solution.14 rigour.Thisis a metaphorworthpursuing,foranyone

who has ever made a filmwillknowthatof allthe arts

The obvious objectionto all this is to ask why it is music which filmmost resembles. Musicis all

we should re-establishan authentic,originalpro- about developmentof mood over time,withchang-

gramme formatwhen we are screening films in a ing speeds, rhythms,orchestrationsand volumes,

modern,verydifferentcontext.Afterall, most mod- allcontributingto a completeexperiencethatkeeps

ern spectators of earlyand silentfilmsare academ- the audience interestedforthe couple of hoursthat

ics, archivistsand historianswho may preferto see a concert mightlast. (Asymphony,of course, likea

films in themed sections to keep their academic featurefilm,has varietybuiltintoit.)

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Stephen Bottomore

but also to balance and react against other kinds of

TIlE KINEMATOGRAPH e LANTERN WEEKLY.

films. Film showmen discovered the magic of pro-

gramming in the early years of the twentieth century,

or more likely inherited it from the vaudeville/music

hall programme. It ill behoves us alleged silent film

lovers to forsake their insights today.

Aesthetics versus information

I have argued above that one effect of the 'filmas art'

aesthetic has been to discourage the programme

format and encouraged the themed retrospective.

But 'filmas art' has not only influenced current festi-

val exhibition practice, it has also influenced how

films are critically studied by film historians and

students. If films are regarded as art objects they

may be seen as having intrinsic aesthetic value,

somewhat apart from the context of their making,

and may be studied merely as a series of images

with no particularhistory. Jacques Aumont has pro-

posed this 'aesthetic approach' as one way of study-

ing film. Inhis keynote statement at the Domitor 1994

conference Aumont suggested that, as well as the

more conventional historical approach to early film

study (which examines the circumstances and man-

ner of film production and exhibition), there is also

room for a purely aesthetic response. In this form of

studying film we do not necessarily need to know

much about the historical background to a particular

film, but can appreciate it merely for its aesthetic

qualities. Eric de Kuyper has taken a similar line in

his study of Alfred Machin's films.15

Fig. 4. Short And surely the point about cinema is that it has This aesthetic approach also seems to have

travelorinterest always been a popular artform, appealing to millions influenced the thinking behind the Amsterdam film

filmswere of people, where audiences were less concerned study workshops, notably that of 1994 on non-fiction

frequently with who made a film than with (pace Hiley again) film, and the workshop on colonial film four years

includedin

an entertaining couple of hours in a cinema. later. The 1994 workshop gathered together a

cinema having

programmes. In short, cinema has always been as much about number of film historians, filmmakers and other in-

[Kinematograph exhibition as it has been about production. terested parties to watch and comment on several

andLantern Yet film archives and retrospective festivals sessions of early non-fiction films, beautifully pre-

Weekly8 often behave as if production and the companies served by the Nederlands Filmmuseum. We viewed

February 1912.] and individuals who produced the films were the only a rich selection of travelogues and industrials from

side of the coin. Film archives spend vast amounts about the first twenty five years of the cinema. The

of time and effort in restoring films as they suppos- workshop aimed to stimulate scholarly reactions to

edly were when originally produced. These restora- these rarely seen reels, in areas such as the visual

tions are presented with great fanfare as 'authentic' style and technique of individual films, and vari-

versions, or 'directors' cuts'. Yet as far as the exhibi- ation/evolution between films.

tion side is concerned, authenticity is sometimes However, it soon became apparent that these

allowed to go out of the window. Films are presented aims would prove problematic. After a couple of

in an inauthentic setting, utterly shorn of the pro- days of viewings, Ben Brewster delivered the devas-

gramme which once gave these films life and con- tating blow. He pointed out that he had noticed a

text, a setting which allowed particularfilms to shine, distinct lack of year-on-year stylistic evolution in

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscovering early non-fiction film 167

these earlynon-fictionfilms.This,he suggested was THE BIOSCOPE. 19li. Fig.5. The

inmarkedcontrastto fictionfilmswhichwerechang- newsreel item

ing informratherrapidlyinthis period,and he noted wasa programme

The Ladies! ' initself,often

it is often possible to date earlyfictionfilmsto within ofa

consisting

a couple of years by stylisticfeaturesalone.16 dozenbriefnews

Was he right?Is silent non-fictionsomething 1)~

Please them by exhibiting fop their benefit I

stories,

of a PeterPanfigureinthe familyof filmtypes? Isthis frequently

a filmgenre thatfailedto growup, orat least showed

relativelylittledevelopmentfor a numberof years?

ITHE PARIS iB including

fashion

a

item.

We need to pickourperiodsverycarefullyhere. Ifwe [TheBioscope 4

are talkingabout the veryearliestyears of filmpro- FASHIONSI August1910.]

duction - the 1890s - it is possible to make the whichappeareveryweekin

contraryclaim:thatcertaintechniquessuch as pan-

ning,cameramovementand multi-shotconstruction Pathe'sAnimated

Gazette.

were probablyfirst used in non-fiction.But when

They frtem a featureof te Gazettewhiclis

fictionwas takingoverfromnon-fictioninimportance appeciated

thoroeughly

at atatinees, ande weaeare constaltly receivicng expres-

from about 1903, the position was apparentlyre- aSinS of iegret fromoaur custoners that tlis particular item is not

of greater length.

|

versed, with more rapid stylistic innovationin the

Those who have not yet commenced to exhibit the Gazette, should

former.And the non-fictionfilmsviewed at Amster- j* bear this fact in mind.

dam that Brewsterwas primarily referringto were in

this second-stage era of early cinema from about

1905 to 1920. WhileIwouldarguethatsome stylistic

developmentis discerniblein non-fictionin this era, is 41 -:

^fi^F-' CrX i' XL iii

there does seem to be much less change than in

fiction films, where editing, lighting,performance, ~:'i::'J? } "'!7

;'

31.33CharinSgCrossRoad 0 L N 0ONN

and various other aspects of film style were all in |,y= 4t!W=tv*====^=====s^=a= ^t-t.

rapidevolutionupto and beyondthe FirstWorldWar.

Inaddition,a move to featureswas takingplace in Elsaesser noted the filmmakers'evidentfascination

fictionfilmsinthis period,leavingnon-fictionfilmsas with recordingentiremanufacturing'processes'. A

usuallythe shortestitemson the programme.Bythe number of other interestinggeneralisationswere

second decade of cinema then, non-fictionmay also made, and anotherby-productof the workshop

indeed be regardedas a relativelystagnantgenre in was instimulatingthe writingof severalusefulessays

termsof filmstyle and technique. whichthe Filmmuseumpublished.17

Itwas my impressionthat Brewster'sremark, Butduringthe workshopitselfthis lightsouffle

moreor less accepted by all present,putsomething of stylisticanalysis was not enough to satisfy the

of a damper on proceedings at the Amsterdam pangs of factualhungerof some in the group. Ed-

non-fictionworkshop.Iftherewas littledevelopment ward Buscombe observed pointedlythat we had

in style, that took away a whole possible area for been offeredlittlehardinformation aboutthe majority

analysisand discussion. Certainlya lackof technical of the films being viewed. Whywas this, he won-

developmentmeantthatthe BarrySaltand Classical dered? Was it because no-one knew, or that the

HollywoodCinemaapproachesto filmstyle analysis information was being deliberatelywithheld'inorder

mentionedabove (lookingat such variablesas edit- to encourageus to thinkforourselves'?Isuspect that

ing and lighting),were likelyto be fruitless.The partof the reason was indeed the latter:the organ-

Amsterdamworkshopwouldhaveto concentrateon isers thoughtthat stylisticanalysis alone mightwell

a narrowertype of aesthetic analysis,less based on illuminatethese films,and thattoo muchinformation

stylisticdevelopment. about theirproductionand content mightget in the

Fortunately,aesthetic approaches did not way of such analysis.The hope was apparentlythat,

prove entirelywithoutvalue, and in the discussion without informationalbaggage, each participant

sessions the participantscame up withsome inter- could view these little-knownfilms with a 'tabula-

esting points: Tom Gunning spoke of the 'vues' rasa'of a mind- and thereforebe forcedto analyse

aesthetic of the films of this period,while Thomas the filmsin a moreoriginalway.

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 Stephen Bottomore

As I'vesuggested, this approachdid lead to detailedanalysisof filmedge markingsand inter-ti-

some interestingcommentsand furtherstudies, but tles, as well as checking on dateable events might

ultimatelymyfeelingwas thatmanyparticipants(not tie an unidentifiedfilmto descriptionsin the trade

only Buscombe) found the 'information-light. view- press or elsewhere, and therefore allow positive

ing experiencesomewhatfrustrating.18 Itis interest- identification,perhaps even includingsuch details

ingto reflectthatsuch a fact-freeenvironmentwould as filminglocationand creativestaff.20

not have been toleratedforfictionfilms.A screening Australia'searlyfilm historyis predominantly

of fictionfilms in which basic information was with- non-fiction,and film historianChrisLong has long

held- aboutdirectors,cast and plots,forexample- been digging into the writtenrecords, which are

wouldsimplyhave been unacceptableto a modern frequentlythe onlyway to identifysurvivingfilmcop-

scholarlyaudience. So is therea good argumentfor ies, fictionor non-fiction.Longpointsout:

screening non-fictionin an informational vacuum?

One thing is clear fromour workto date: the

The firstthing to say is that in many cases

fullsignificanceof earlyfilmmaterials- gener-

furtherbackgroundinformationwas probablynot

knownfor the films shown at Amsterdam,and in ally lacking credits and titles- is rarelyre-

vealed by the films alone. Plumbing their

general there are major problems in discovering

such information, or even in identifyingearlynon-fic- significancedemands patientprimaryhistori-

cal researchand the endless posing of often

tion. This was made clear to me a couple of years

beforethe Amsterdamworkshop.ScholarJeannine straightforwardbut specific questions such

as: Whomade the films?Whereand howwere

Baj was then studying early films held in the

they produced? Who funded them? Why?

CinemathequeRoyale in Bruxelles,and sent me a Whereand how were they shown?Whowere

listingof abouta hundredtitlesof their'documentary' the audiences and how were they brought

films. Mostof these (allbut about 15 titles)had the

together? What productions have survived

dreaded bracketsaroundthe title.As all filmarchi-

and why?... Archivalpreservationand identifi-

vists know, brackets often indicate a title that the

cation can proceed effectivelyonly on the

archivehas attributedto the film,in the absence of

basis of wide ranging,detailedprimaryhistori-

knowingthe original,real title. Most of the films, in cal research. The two must proceed in tan-

otherwords, had not been identified,and the case

dem.21

of the Bruxellesfilmsis probablynotatypicalof other

film archivecollections, which also contain a high Thisprocess of fillingin backgroundinforma-

numberof non-fictionfilmswhere even such basic tion sometimes relies on unusualor raresources. I

details as the productioncompany are not known. was recentlylookingat the collectionof cameraman

Whilefictionfilms may often be identifiedthrough EmileLauste,held at the SouthEast Filmand Video

theirtitles and cast lists, whichoften surviveor can Archivein Brighton.Lauste,the son of sound-on-film

be deduced, in non-fictionthere are no performers experimenterEugene Lauste,was an importantpio-

to recognise, and few 'creativestaff',such as cam- neer in his own right,and shot a numberof non-fic-

eramen,were ever credited.19So researchingnon- tion films in the early years of the 20th century.

fictionis morecomplicatedthan researchingfiction, Among his collection are a series of photographs

and it must be said that many film archivistsand showing a northern,snow-covered location,witha

historiansare not used to checking background group of explorersin distinctivefurcostumes, and

details on the places and historicalevents and per- using equallydistinctivevehicles. A few days laterI

sons whichmay help elucidatethese films. happened to be viewing some films at the NFTVA

Yet it is possible to findout information about and saw the same distinctivebackgroundsand peo-

early non-fictionfilms, and some archivesand film ple in a particularly well shot film of the Wellman

historians have started filling in the gaps. The Expedition(1906). thanksto the Brightonstillswe

So

NFTVA'snon-fictioncatalogues often reveal much now suspect that this filmwas shot by Lauste,and

informationabout the archive'sfilms, found partly to judge fromthis example,he was a cameramanof

throughresearchingnon-filmsources. The research some talent.

departmentof the NederlandsFilmmuseumhas also As wellas helpingin identification, extrainfor-

been notablysuccessful inthiswork,withtheirBiog- mationreallyis vitalinbetterappreciatingnon-fiction

raph holdings for example. In some cases a more films(andhereIwoulddefinitively partcompanywith

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscovering

~ ~ early

:BBB&BBb<WEX2a; ~ non-fiction

- -...... ."..' ' film 169

Fig. 6.

Cameramen like

thesefrom

Pathe'snewsreel

wouldmake

detailednotes

aboutwhatthey

hadshoton

location,so that

post-production

staffcouldmake

senseoftheir

rushes.

[PatheCinema

Journal 4 April

1914.]

the 'aesthetic' school). Indeed it can sometimes be as 1908 film executive Thomas Clegg described the

the only way of giving any significance or importance qualities expected of a film cameraman in the field.

to otherwise dull and meaningless pieces of celluloid In addition to his technical and diplomatic skills, a

held by film archives. As any documentary filmmaker good operator should have a 'capacity for descrip-

will testify, there is often nothing inherently interest- tive comment', for he needed to write down 'copious

ing or uninteresting in a shot, apart from production notes', with the details of who and what he had shot

informationor lack of it invested in that shot. A piece (in addition to recording technical informationabout

of film found in an archive showing troops marching light conditions, lens stop used, etc).22 This was in

through a muddy field may seem quite uninteresting. order that back at head office the significance of the

But if it can be dated and identified the significance images could be understood, and they could be

increases, and if it turns out that it was shot during a edited together (along with intertitles) to create an

key historical period in a certain country's history, accurate and interesting travelogue or news film.

then its value to that country increases enormously, Clegg related the sad case of one otherwise

even if the film itself is in aesthetic terms quite 'brilliantoperator', a cameraman who 'fearlessly ven-

'uninteresting'. In other words, in the realm of non- tured into situations of grave peril ... and secured his

fiction film, aesthetics is often of less significance pictures', but who had one failing: he 'could give

than background information. Whata film is is more simply no information respecting the situation'. In

importantthan how it is. other words, he would never provide a good written

Even in the early days of non-fiction filmmak- description of what he had shot, and the only details

ing this crucial importance of background informa- he supplied were of the vaguest kind: 'That's a hill-

tion was understood. When a cameraman went on a the other is an elephant. In the distance is a

filming expedition he was expected to note down mosque.'23 Such vague notes were too imprecise to

details of the place or event that he had shot, and to guide the process of post-production, in which ap-

describe what was going on - information that was parently meaningless shots taken on location would

not necessarily clear from the images alone. As early be shaped into a filmstory, about the particularplace

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

170 Stephen Bottomore

or event, using informationrecorded during the film- would give the images significance and interest. I

ing process. This information was used to write have argued above that both of these presentation

intertitleswhich would contextualise the film images decisions may be traced back to the 'film as art'

for the audience, or to provide details for a verbal movement, in which films are seen as having intrinsic

description in cases where a lecturer would accom- visual worth, and should be grouped together, as in

pany the films (especially likely for longer 'feature' an art gallery, to be better studied.

documentaries - such as the Kinemacolor Durbaror But, while some early non-fiction films can

Rainey's AfricaHunt). stand up to such high standards of artistic scrutiny,

For audiences of the time, most non-fiction sadly many do not, and never did. Likeso many other

films without such added background informationin examples from the history of the moving image,

the form of intertitles would have been indigestible these were programme-fillers: workaday strips of

to say the least. For viewers today one might argue celluloid, with no particularclaim to art. Served up in

that even more information is required, for they of moderation they meant something to audiences of

course know so much less about the world of the the time, as part of a mixed programme of drama,

early 20th century. The pre World War One viewers comedy, non-fiction and news. But there is little

were already mired in the events of their time. For reason to suppose that all of these same films should

such viewers, watching the capture of the Bonnot mean anything special to audiences, or indeed

gang in 1912, for example, would have been a real scholars, of today. We would certainly be right to

thrill, for in all probability they had already been assume that a block of five early travelogues and

reading about these notorious characters and the contextless news reports shown together is just as

crimes they had been committing. But there is no likelyto bore a modern festival audience as it would

reason why a modern audience, without such fore- be guaranteed to have patrons of The Bijou Dream

knowledge, should have any emotional connection in 1913 demanding their money back.

with these gray shadows from a formerage. A 'purely But happily I do see some evidence that

aesthetic' experience of such images, if it is possible change is coming in the practice of presenting silent

at all, must surely be a very impoverished one. Ifwe films. Witness the imaginative way that the Film-

do not understand what something is, we will also museum in Amsterdam has organised their 300 Bi-

have a much reduced appreciation of any aesthetic ograph films into programmes, which to some extent

qualities it might have. mix up the genres. The Pordenone festival is also

On this basis I would hope that for future improving in this respect in that the different strands

screenings of early non-fiction, background informa- of the festival programme are often broken up into

tion should be researched and programme notes be shorter, 'bite-size' sections than used to be the case,

provided, or introductoryon-screen titles be added, thus in effect introducing more of a variety feel.

aiming to offer the audience the same level of infor- But my suggestion would be to extend these

mation, or higher, as is already de rigeur in present- welcome developments in silent film programming,

ing fiction films. especially for showing early non-fiction. I would ar-

gue that the way to give non-fiction films life and

significance is to offer them in small doses and with

Conclusion appropriate information. Rather than presenting

Itseems to me that the major 'retrospectives' of early large groups of scientific or travel films one after the

non-fiction in recent years have moved too far away other, it would be better to show them in smaller

from the exhibition practice of the era in which the numbers. One way to do this would be to re-establish

films were produced and shown. Firstly,by program- a certain number of mixed-genre film programmes,

ming many similarfilms together as a block, flying in more or less as they were at the time of the films'

the face of the mixed programming formatwhich was original release. I believe that these kind of presen-

always their original context. And secondly by tend- tations would improve the viewing experience, and

ing to present the films as aesthetic objects, often allow a new audience to appreciate these living

shorn of the background factual information which records of a former century.

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscovering early

.. I.. .. ..

non-fiction film 171

262

Fig.7. This

THE BIOSCOPE,

APRIL24, 1913. a

invention,

onthe

variation

There is no need to ask "What's On ?" programme

THE - notonly

board,

THE i I showed theentire

LATEST ! AUTOGRAMME programme, but

which

highlighted

FINEST!! (PATBNTED) filmwasshowing

BEST!! TELLS ateachmoment.

[TheBioscope24

EVERYBODY PR 1913.]

April

N0 v

ANY Number THAT.

workedby ONE

Switch under the , BeautifullyFinished

Control of the c

for Inside and Out-

Operator. . . . : side Positions. :

I

The Autogramme TH

gives a Finish to

: yourTheatre.:

For particulars and

orcall

prices,write,wire

& CO.,

GRUNDY

68, VictoriaStreet,

Westminster, s.w. I

fill-

II III III /11 ~I iiUli

Appendix mind interestinghabits, industriesand cus-

Programming non-fiction in the toms of othercountries.The brainis given a

1910s rest,forlittlementalactivityis requiredto prop-

Whileit is clearthatnon-fictionfilmswere unlikelyto erlyappreciatesuch subjects, indeed, an in-

be the actual 'draw'on a cinema programmein the telligentman sufferingfrombrain'fag'derives

teen years, it seems that in limiteddoses such films considerable enjoyment by witnessing pic-

were greatlyappreciatedby audiences. In 1911 Ki- tures of this description.24

nematographand LanternWeeklysuggested that a On the other side of the Atlanticthis idea of

certaintype of spectator 'likesto see the realthing educationalsas 'rest'was also being argued. Per-

occasionally,and not to be surfeitedwiththe stagey haps the king of exhibitionin Americaby the teen

film'.Thejournalwent on to ask whysuch filmswere years was Samuel L. Rothapfel,manager of the

liked by so many spectators. Was it, perhaps to Strandtheaterin NewYork.In1914 'Roxy',as he was

providesome stimulationforthe mind,incontrastto laterknown,described his exhibitionphilosophyto

the easy-viewing,vacuous comic and melodramatic the Moving Picture World, explaining that the

films? Quite the reverse according to the 'Kine', lynchpinwas the programme:

whichclaimedthatfactualsprovideda kindof 'rest'

The programmust representsomethingas a

in the programme:

whole, it mustbe a fittingprogram,a program

withan atmosphereof its own.25

Thereare manybusy commercialmen whose

brainsare taxed to the utmostlimitallday and To this end, a careful selection and skilful

to such thereis somethingrestfuland pleasant combinationof the elements was crucial.A drama

in seeing projectedscenes conveyingto the should be selected based on its 'powerof tugging

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

172 Stephen Bottomore

at the heartstringswithoutcausing the disagreeable 'educationals',out of bitsof existingfilms,especially

effectof a severe strain'.Comediesshouldbe 'clean' coloured or tinted scenes, and incorporatingele-

(thoughin Rothapfel'sviewthis did not ruleout 'slap mentsof the dramaticorcomic (inpicturesof animal

stick' or 'roughhouse'). News filmswere also very life,for example).Theyassembled the elements so

importantat the Strand.Knownas 'topicalreviews', thatthe strongestscene was usuallythe last.

these were specially compiled by the Strandstaff, Rothapfelwas not particularly in favourof the

and were, as Rothapfelnoted, verypopularwiththe growingmove in the 191Ostowardslonger'feature'

theatre's higherclass patrons, 'who wait for these films.He stressed thateveryfilmof whateverlength

reviewswitha child'senthusiasmforthe coming of in one of his programmeshad its own strengths:

Santa Claus'.

'Educationals'(as non-newsfactualfilmswere Qualityis the only real featurein my eyes. It

has happenedtimeand againthatthe feature,

sometimes called in the earlyfilmera) were a key

so called, on my programhas been dwarfed

buildingblock of a Rothapfelprogramme.He had

often noticed 'the deep interest which holds our by some otherpartof the entertainment.By a

audiences when the "educational"partof the pro- splendidscenic forinstancewithbeautifulmu-

sic, by a particularlyappropriatetopicalreview

gram is being displayed on the screen'. Rothapfel

or by some otheritemon my weeklyoffering.

attributedthe same strategicroleto these non-fiction

I do not thinkit is sound policyto relyon just

films in regulatingpace as the Britishwriterquoted

one partof yourprogramand trustto itto pull

above, theirfunctionbeing 'to rest the audience'. In

a two hourprogrammespectatorswouldnotwantto throughthe rest.

be continuallystimulatedby exciting dramas, and Not everyone thought that factual films had

withno intervalin the show (unlikein the theatre),a such appeal. An authorin the Worldsuggested that

factual film could introducea differentmood be- these films were positivelydisliked by audiences,

tween the emotionalfictionfilms: and that'theleast welcome of the educationalseries

are the scenics' (largelybecause they needed a

Take your audience at the conclusion of a

lecturer,he thought).Thiswritersuggested thatthe

strongclimaxof a strongdrama.Icannotthink mainreasonfor

of catapultingan audiencethus set to thinking includingsuch filmsina programme

was entirelycynical:

and lifted out of itself, into a ripe, roaring

comedy. I therefore show them something It is picturesof the educationalseries, then,

whichdelightsthe eye and soothes the mind which give tone to an exhibition;not only im-

without touching any emotional chords. partlifeand characterbut they drawthe best

Scenes of beautifulfountains or waterfalls, people, encouragethe attendanceof children,

dainty bits of animal life, scenes from the make censorship less necessary, and defy,

beautifulcountriesof the world,monumentsof yea, even destroycriticism.26

architecture,glimpses of foreign lands and

Butthiswriterwas probablyin a minority,and

foreignnationsmost admirablyfillthe interval it is that most showmen, certainlyin Britain,

which ought to come between the dramatic likely

were with Rothapfel in believing that audiences

and the comic.

genuinely liked a few non-fictionfilms in the pro-

Interestingly,as with news films, Rothapfel's gramme,and such filmscontinuedto be produced

theatre seems to have custom-assembled its own and shown formanyyears to come.+

Notes

1. Thisdespite the effortsof DavidFrancis,who suggested that earlyfactualfilmsmighthave had a greaterinfluenceon laterfilmstyle

thanearlydramaticfilms.See HistoricalJournalof Film,Radioand Television11/3, (1991):280.

2. ArthurEdwinKrows'series of articles,'Motionpictures- notfortheatres'appearedin TheEducational Screen betweenSeptember1939

and 1944. The articleshave not been reprinted,and I had to chase up runsof the journalin three librariesbeforeI could locate every

history.Highlyanecdotalthoughit is, this is the most completehistoryof industrialand sponsoredfilmmakingin

issue of this multi-part

Americaup to the 1930s thatexists, fullof names of companiesand individualswhowere involvedin a thrivingindustrythatfilmhistory

has all but forgotten.AnthonySlide is aboutthe onlyfilmhistorianwho has made use of Krows'work:see Slide's usefulbook, Before

Video: a Historyof the Non-TheatricalFilm (NY/London:Greenwood Press, 1992).

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rediscovering early non-fiction film 173

3. RudolfArnheim'soriginaltitlewas FilmAlsKunst(Berlin:E. Rowohit,1932).Itappearedin Englishas simplyFilm(London:Faber,1933).

4. PaulRotha,DocumentaryFilm(London:Faberand Faber,1936):77.

5. On 'hybrids'in particularsee: BillNichols,BlurredBoundaries:Questionsof Meaningin Contemporary Culture(Bloomington:Indiana

UniversityPress, 1994) and CharlieKeil,'Steel engines and cardboardrockets:the status of fictionand non-fictionin earlycinema',

Persistenceof Vision,no.9, (1991):37-45.

6. AlanRosenthal,New ChallengesforDocumentary(Berkeley:University of California

Press, 1988) KevinMacDonaldand MarkCousins,

ImaginingReality:the FaberBookof the Documentary(London:Faber,1996).

7. CharlesMusser,'Documentary' in GeoffreyNowell-Smith,

ed., TheOxfordHistoryof WorldCinema(Oxford:OUP,1996).

8. Note forexamplethe workof AlisonGriffiths, RolandCosandeyand JenniferPeterson.

9. Moregenerallyone detects an increasinginterestin non-fictionof all periods,witnessed,forexampleby the foundingin 1994 of the

IDA/AMPASA DocumentaryCenterat the Academy.See 'News fromthe Affiliates',Journalof FilmPreseivation48, (1994): 18. The

indexingof Britishnewsreelsby the BUFVCand the BritishPath6archiveshouldalso stimulatethis interest.

10. Allthis is not to deny thatNanookof the Northwas a pioneeringeffort,principally because itwas a narrative-led filmaboutone family,

in contrastto the less personalstudies of places and activitiesof most previousnon-fictionfilms.

11. TheBioscope (Bios)(10 March1910):20.

12. 'Representativekinematograph shows: 1. AnexamplefromPoplar',Kinematograph and Lanter Weekly(KLW) (11 July1907):142.

13. LetterfromT.J.West, 'Whatthe publicwants',Bios (26 February1914):955.

14. The proceedingsof the AmsterdamFilmmuseum'sthirdWorkshopare accessible on its website:www.filmmuseum.nl. Thisworkshop,

entitled'Theeye of the beholder:colonialand exoticimages',was heldinthe Summerof 1998.ThequotationfromHileyis fromthe end

of the finalsession, session 6. Muchof Hiley'sworkhas focused on the audience in the silentand earlysound eras, and he has also

discussed the rationaleof the cinemaprogramme.

15. EricDe Kuyper,AlfredMachin(Bruxelles:Cin6mathequeroyalede Belgique,1995).

16. See Daan Hertogsand Nicode Klerk,eds., Nonfictionfromthe Teens (Amsterdam: StichtingNederlandsFilmmuseum,1994):32.

17. See Daan Hertogsand Nico de Klerk,eds., UnchartedTerritory: on

Essays Early Nonfiction Film(Amsterdam:StichtingNederlands

Filmmuseum,1997).

18. Thisfeelingwas encapsulatedin AlisonGriffiths' remarkat the end of one of the sessions of the Amsterdamcolonialismworkshop:

'Groundingsome of these issues in primaryevidencewouldbe a veryusefulmethodologicalapproach.'

19. I suspect thatforsome filmhistorians,comingfroma humanitiesbackgroundwherethe 'author'of the text is of centralconcern,the

paucityof names maycontributeto theirlackof interestin non-fiction.

20. Forexamplesome of the BruxellesfilmswhichI mentionedmightbe identifiedinthese ways, such as Une Eruption de I'Etna.

21. ChrisLong, 'World'sfirstgovernmentfilm production?'in Ken Berryman,ed., Screeningthe Past: Aspects of EarlyAustralianFilm

(Canberra: NFSA,1995):37. Forthose who liketo puta nameto a thing,earlyfilmhistorianThierry Lefebvrehas calledthissupplementary

information the 'paratexte'of a film.

22. CameramanEmileLauste'ssmall ledgerwithsuch technicaldetails noted on location,survivesin the LausteCollectionin the South

East Filmand VideoArchive,Brighton.

23. See ThomasClegg, 'Afascinatingindustry',KLW(15 October1908):547.

24. 'Use of educationalfilms',KLW(31 August1911):907. Thoughthe journaladded thatthe un-professionalclasses of spectatormight

preferotherkindsof films.

25. W.Stephen Bush, 'Theartof exhibition',MovingPictureWorld(MPW)(17 October1914):323.

26. 'Thepictureswhichgive tone to an exhibition',MPW(11 May1912):506.

This content downloaded from 91.229.248.202 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 00:47:27 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Kinoglasnost in CinemaDocument2 pagesKinoglasnost in CinemaManuela MorarNo ratings yet

- TRANSNATIONAL CURRENTS IN Latino American CINEMADocument266 pagesTRANSNATIONAL CURRENTS IN Latino American CINEMAManuela MorarNo ratings yet

- OlympiaDocument50 pagesOlympiaManuela MorarNo ratings yet

- Cine VeriteDocument86 pagesCine VeriteManuela MorarNo ratings yet

- The New Yorker - 17 01 2022Document76 pagesThe New Yorker - 17 01 2022Karl Leite100% (1)

- GunulaDocument2 pagesGunula2ooneyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press, The Classical Association Greece & RomeDocument15 pagesCambridge University Press, The Classical Association Greece & Romerupal aroraNo ratings yet

- Russian Dance: Pyotr Ilyich TchaikovskyDocument4 pagesRussian Dance: Pyotr Ilyich TchaikovskyДмитрий ДевотченкоNo ratings yet

- Arts and Crafts Subject CurriculumDocument7 pagesArts and Crafts Subject CurriculumJohny VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- A Brush With Art PDFDocument104 pagesA Brush With Art PDFNuno Maneta100% (2)

- Multiple IntelligencesDocument5 pagesMultiple IntelligencesE-Link RosarioNo ratings yet

- Etude1 Synopsis - Jimmy Wyble (Dragged) 3Document1 pageEtude1 Synopsis - Jimmy Wyble (Dragged) 3Kerem AdvanNo ratings yet

- Q1 W2 Arts 7Document2 pagesQ1 W2 Arts 7Christian Don VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Summative Test in MAPEHDocument4 pagesSummative Test in MAPEHEdgar ElgortNo ratings yet

- Fiddle FuryDocument12 pagesFiddle FuryHelene PeloNo ratings yet

- Notes On Digital Uncanny by Kriss Ravetto-BiagioliDocument6 pagesNotes On Digital Uncanny by Kriss Ravetto-BiagioliShini WangNo ratings yet

- Blue Frilled Sea Slug: MaterialsDocument3 pagesBlue Frilled Sea Slug: MaterialsyopatmetNo ratings yet

- CPAR 12 - Lesson 2Document25 pagesCPAR 12 - Lesson 2Laurenz De JesusNo ratings yet

- Corridos and Al Otro Lado Lesson GuideDocument88 pagesCorridos and Al Otro Lado Lesson GuidegustiamengualNo ratings yet

- Dca 6163 - Measured Drawing: Task 1: Building ProposalDocument11 pagesDca 6163 - Measured Drawing: Task 1: Building ProposalHafy NazieraNo ratings yet

- Arts and ScienceDocument3 pagesArts and SciencesunnyNo ratings yet

- Ancient Pottery (From 18,000 BCE) : Evolution of ArtDocument13 pagesAncient Pottery (From 18,000 BCE) : Evolution of ArtyowNo ratings yet

- Thesis About Television ShowsDocument5 pagesThesis About Television Showscathybaumgardnerfargo100% (2)

- Deus Ex Machina (/ Deɪəs Ɛks MækɪnəDocument41 pagesDeus Ex Machina (/ Deɪəs Ɛks MækɪnəYohanes MteweleNo ratings yet

- Common Dance TermsDocument6 pagesCommon Dance TermsRaven ShireNo ratings yet

- MCQ English Literature PDFDocument82 pagesMCQ English Literature PDFLutfor LitonNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 Music 3rd QuarterDocument38 pagesGrade 8 Music 3rd Quarternorthernsamar.jbbinamera01No ratings yet

- Per Kirkeby: RetrospectiveDocument19 pagesPer Kirkeby: RetrospectivedavwwjdNo ratings yet

- Objective/Balanced Review or Critique of A Work of Art, An Event or A ProgramDocument20 pagesObjective/Balanced Review or Critique of A Work of Art, An Event or A ProgramJordanNo ratings yet

- Frameless Glazing Using Spider Fittins & Patch FittingsDocument22 pagesFrameless Glazing Using Spider Fittins & Patch FittingsJahnavi JayashankarNo ratings yet

- Q2 Music 8 - Module 1 PDFDocument16 pagesQ2 Music 8 - Module 1 PDFkateNo ratings yet

- Idoc - Pub Origami Tiger Satoshi Kamiya DiagramsDocument13 pagesIdoc - Pub Origami Tiger Satoshi Kamiya DiagramsTrọng ĐinhNo ratings yet

- Anstey - Tenants Furniture - KogKDocument13 pagesAnstey - Tenants Furniture - KogKTim AnsteyNo ratings yet

- GE6 Content AA Module 9Document13 pagesGE6 Content AA Module 9MikeKhel0% (1)