0% found this document useful (0 votes)

374 views48 pagesPlasticity

The document discusses plasticity, which is the property of materials to undergo permanent deformation. It covers the classical theory of plasticity, which grew out of studying metals in the late 19th century. Plasticity involves materials initially deforming elastically, then plastically once reaching the yield stress. The document also discusses assumptions of plasticity theory, classifications of plasticity problems, generalized plasticity models, and perfectly plastic deformation behavior.

Uploaded by

MUHAMMADYASAA KHANCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

374 views48 pagesPlasticity

The document discusses plasticity, which is the property of materials to undergo permanent deformation. It covers the classical theory of plasticity, which grew out of studying metals in the late 19th century. Plasticity involves materials initially deforming elastically, then plastically once reaching the yield stress. The document also discusses assumptions of plasticity theory, classifications of plasticity problems, generalized plasticity models, and perfectly plastic deformation behavior.

Uploaded by

MUHAMMADYASAA KHANCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

- Introduction to Plasticity: This section introduces the concept of plasticity, setting the stage for the detailed discussions in subsequent sections.

- Theory of Linear Elasticity: Explains the principles of linear elasticity, focusing on reversible deformations and their significance in material science.

- Classical Theory of Plasticity: Discusses the development of plasticity theory, highlighting key historical advancements and contributors.

- Classification of Plasticity Problems: Outlines the different types of plasticity problems encountered in engineering, focusing on strain classification.

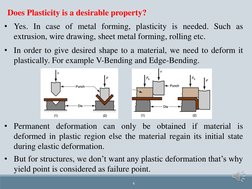

- Desirable Properties of Plasticity: Explores why plasticity is favored in metal forming and its benefits over other materials processes.

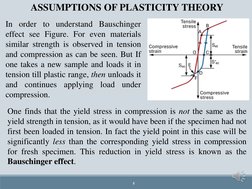

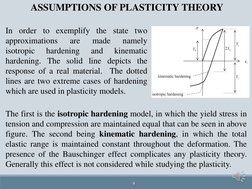

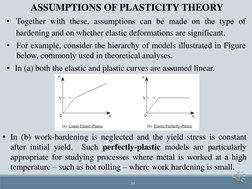

- Assumptions of Plasticity Theory: Details key assumptions underpinning plasticity theories, which form the foundation for modeling in engineering.

- Generalized Plasticity Model: Introduces a model for understanding stress-strain relationships in plastic deformations.

- Perfectly Plastic Deformation Behavior: Explains the behavior of materials undergoing perfectly plastic deformation, emphasizing volume consistency.

- Strain Hardening and Flow Rule: Describes the mechanisms behind strain hardening and the theoretical flow rules in materials science.

- Viscoelastic and Viscoplastic Behavior: Differentiates between viscoelasticity and viscoplasticity in material behavior, with emphasis on rate dependence.

- Failure Theories (Yield Criteria): Overviews different yield criteria applied to predict material failure in ductile and brittle materials.

- Failure Theories for Ductile Material: Details failure theories specific to ductile materials using different stress and strain criteria.

- Failure Theories for Brittle Material: Outlines theories relevant to the failure of brittle materials, distinguishing them from ductile materials.

- Problems and Solutions: Provides practical problems and solutions using discussed theories to apply concepts in real-world scenarios.