Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 203.175.72.26 On Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

Uploaded by

Shujat AliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 203.175.72.26 On Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

Uploaded by

Shujat AliCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating Value for Individuals, Organizations, and Society

Author(s): Michael A. Hitt, R. Duane Ireland, David G. Sirmon and Cheryl A. Trahms

Source: Academy of Management Perspectives , May 2011, Vol. 25, No. 2 (May 2011), pp.

57-75

Published by: Academy of Management

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23045065

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Academy of Management Perspectives

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 57

ARTICLES

Strategic Entrepr

Creating Value for Indivi

by Michael A. Hitt, R. Duane Ireland, David

Executive Overview

The foci of strategic entrepreneur

disciplines such as economics, psychol

including organizational behavior an

strategic management and entrepre

input-process-output model to extend

inputs into SE, such as individual kno

processes that are important for SE a

wealth for stockholders, and creatin

Individual entrepreneurs also benef

satisfaction and fulfillment of person

importance. Therefore, we incorporat

neurs.

individuals, organizations, and/or society. This

cant practical relevance in the current and means that SE involves actions taken to exploit

An projected

important economicscholarly

environments question

is how with signifi current advantages while concurrently exploring

firms can create value, an end goal of both stra new opportunities that sustain an entity's ability

tegic management and entrepreneurship (Bruyat to create value across time. The need to under

& Julien, 2001; Meyer, 1991). In particular, how stand how new ventures can achieve and sustain

do firms create and sustain a competitive advan success by exploiting one or more competitive

tage while simultaneously identifying and exploit advantages and how large established firms can

ing new opportunities? This is the primary ques become more entrepreneurial provides incentives

tion on which strategic entrepreneurship (SE) is to theoretically explain and empirically explore

based, placing it at the nexus of strategic man the SE construct.

agement and entrepreneurship. Thus, SE is con Work on SE began in earnest early in the 21st

cerned with advantage-seeking and opportuni century (Hitt, Ireland, Camp, & Sexton, 2001;

ty-seeking behaviors resulting in value for Ireland, Hitt, Camp, &. Sexton, 2001). Ireland,

* Michael A. Hitt (mhitt@mays.tamu.edu) is Distinguished Professor; Joe B. Foster '56 Chair in Business Leadership, Management

Department, Mays School of Business, Texas A&M University.

R. Duane Ireland (direland@mays.tamu.edu) is Distinguished Professor, Conn Chair in New Ventures Leadership, Management Depart

ment, Mays School of Business, Texas A&M University.

David G. Sirmon (dsirmon@mays.tamu.edu) is Pamela M. and Barent W. Cater '77 Faculty Research Fellow and Assistant Professor,

Management Department, Mays School of Business, Texas A&M University.

Cheryl A. Trahms (ctrahms@mays.tamu.edu) is a Ph.D. Student and Research Assistant, Management Department, Mays School of

Business, Texas A&M University.

Copyright by the Academy of Management; all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, e-mailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder's express written

permission. Users may print, download, or e-mail articles for individual use only.

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

58 Academy of Management Perspectives May

Hitt, and Sirmon (2003) developed

evolves with the purpose of achieving an array of an initial

model of SE with four

objectives key

that are important dimensions:

to a firm's stakehold (1) the

ers. Hitt, culture,

entrepreneurial mindset, Ireland, and Hoskisson (2011, p.and 6) leadership,

(2) the strategic management

defined strategic management as "theof

full set of organizational

resources, (3) application ofand actions

commitments, decisions, creativity,

required for and (4)

development of innovation.

a firm to achieve strategicBased

competitiveness and on additional

research and critical examination of the SE con earn above-average returns." With a strong focus

on outcomes, Makadok and Coff (2002) sug

struct, Kyrgidou and Hughes (2010) suggested

that this model lacked the robustness required gested

to that strategic management's purpose is to

positively influence the firm's ability to gener

capture the gestalt of SE. Supporting this assertion

is recent evidence suggesting that SE is broader ate

in profits.

scope, multilevel, and more dynamic (Chiles,Strategic management scholars seek to under

stand the causes of performance differentials

Bluedorn, & Gupta, 2007; Hitt, Beamish, Jackson,

& Mathieu, 2007; Rindova, Barry, & Ketchen, across firms (Ireland et al., 2003; Schendel &

2009) than was originally conceptualized. Hofer, 1978). Effective competitive positioning is

To contribute to the continuing development

a primary factor influencing a firm's ability to

of this young and dynamic field of inquiry requirescreate value and wealth for stakeholders and the

broader society (Ketchen, Ireland, & Snow, 2007;

a richer model of SE. Thus, we extend the original

SE model to incorporate a multilevel and broaderPorter, 1980). Similarly, the firm's idiosyncratic

domain (see Shepherd, 2011). The enhanced stock of resources influences efforts to achieve

model of strategic entrepreneurship presented these outcomes (Barney, 1991). Learning how to

herein integrates environmental influences, ex acquire, bundle, and leverage the firm's idiosyn

plains how resources are managed in the process cratic

of resources is critical to achieving a compet

SE to create value across time, and describes sev

itive advantage and creating value (Chen, 1996;

Sirmon, Hitt, & Ireland, 2007).

eral different outcomes, thereby providing a more

complete view of SE.

Entrepreneurship

The new model, discussions of resource orches

tration, and unique outcomes of SE produce Entrepreneurship

a is a developing discipline that

number of valuable and important questions has begun to blossom in recent years, yet there is

warranting scholarly examination to advance our

a lack of agreement on precisely what constitutes

knowledge about SE and its application in orgaentrepreneurship (Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin, &

nizations. Frese, 2009). One definition frames the activities

required for entrepreneurship to be engaged. In

Integration of the Relevant Research this context, Davidsson (2005, p. 80) offered what

he labeled as three partly overlapping views of

separate disciplines offering unique opportuni entrepreneurial activities: "(1) entrepreneurship is

Strategic management

ties for scholarly andthatentrepreneurship are

inquiry as well as insights starting and running one's own firm; (2) entrepre

inform managerial and entrepreneurial practice neurship is the creation of new organizations; and

(Schendel &. Hitt, 2007). As a foundation for SE, (3) entrepreneurship is ... the creation of new

we briefly summarize relevant research in these to-the-market economic activity." Criticizing the

two domains.

tendency for scholars to define the entrepreneur

ship domain strictly in terms of the entrepreneur

Strategic Management and what he or she does, Shane and Venkatara

Creating competitive advantages and wealth are man (2000, p. 218) offered a more expansive

at the core of strategic management (Chen, definition, saying that the "field of entrepreneur

Fairchild, Freeman, Harris, &. Venkataraman, ship [is] the scholarly examination of how, by

2010). Andrews (1971) defined corporate strategy whom, and with what effects opportunities to

as a pattern of organizational decisions that create future goods and services are discovered,

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 59

evaluated, and exploited." Thus, Shane and Ven concerned about growth, creating value for cus

kataraman argued that entrepreneurship involves tomers, and subsequently creating wealth for own

sources of opportunities; the processes of discovery, ers" (Hitt & Ireland, 2005, p. 228). A significant

evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities; and amount of scholarship focuses on the need for firm

the set of individuals who discover, evaluate, and outcomes to create wealth only or primarily for

exploit opportunities. Consistent with the Shane shareholders. SE expands the scope to which a

and Venkataraman definition, Hitt et al. (2001, p. firm's wealth-creating outcomes can apply to mul

480) defined entrepreneurship as "the identifica tiple stakeholders, including society at large

tion and exploitation of previously unexploited (Schendel & Hitt, 2007).

opportunities." Ireland et al. (2001, p. 51) ex SE allows those leading and managing firms to

panded this definition primarily to include a focus simultaneously address the dual challenges of ex

on wealth creation as an outcome of entrepreneur ploiting current competitive advantages (the pur

ship: "We define entrepreneurship as a context view of strategic management) while exploring for

specific social process through which individuals opportunities (the purview of entrepreneurship)

and teams create wealth by bringing together for which future competitive advantages can be

unique packages of resources to exploit market developed and used as the path to value and

place opportunities." wealth creation. Because "concentrating on either

However, to generate wealth first requires cre strategy or entrepreneurship to the exclusion of

ating value. Entrepreneurs create value by lever the other enhances the probability of firm ineffec

aging innovation to exploit new opportunities and tiveness or even failure" (Ketchen et al., 2007, p.

to create new product-market domains (Miles, 372), SE involves both entrepreneurship's oppor

2005). More specifically, "value creation is the act tunity-seeking behaviors and strategic manage

of obtaining rents (widely defined as financial, ment's advantage-seeking behaviors and is useful

social, or personal) that exceed the total costs for all organizations, including family-oriented

(which may or may not include average rates of firms (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003; Webb, Ketchen, &

return for a particular industry) associated with Ireland, 2010). Relatively speaking, successfully

that acquisition" (Bamford, 2005, p. 48). There using SE challenges large, established firms to

fore, generating wealth through value creation learn how to become more entrepreneurial and

is entrepreneurship's central function (Knight, challenges smaller entrepreneurial ventures to

1921). learn how to become more strategic.

Strategic Entrepreneurship

As our discussion shows, strategic management An Input-Process-Output Model of Strategic

and entrepreneurship are concerned with creating Entrepreneurship

value and wealth. In the main, entrepreneurship

contributes to a firm's efforts to create value and land et al., 2003) and draw insights from pre

subsequently wealth primarily by identifying op Here,

viouswe build

research on athe

to present initial

multilevel input model of SE (Ire

portunities that can be exploited in a marketplace, process-output model for the purpose of providing

while strategic management contributes to value a richer understanding of the SE construct. The

and wealth-creation efforts primarily by forming SE model we advance incorporates environmen

the competitive advantages that are the founda tal, organizational, and individual foci into the

tion on which a firm competes in a marketplace. dynamic process of simultaneous opportunity- and

Therefore, entrepreneurship involves identifying advantage-seeking behaviors. When used effec

and exploiting opportunities, and strategic man tively, these behaviors create value for societies,

agement involves creating and sustaining one or organizations, and individuals.

more competitive advantages as the path through The SE model presented in Figure 1 identifies

which opportunities are exploited. Thus, both three dimensions: resource/factor inputs, resource

strategic management and entrepreneurship "are orchestration processes, and outputs. The first di

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

60 Academy of Management Perspectives May

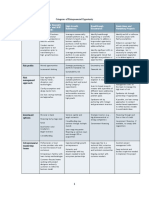

Figure 1

Input-Process-Output Model of SE

mension specifies the resources/factors serving as external environment and the firm affects perfor

the SE process inputs at different levels, including mance (Keats & Hitt, 1988) and long-term sur

environmental factors, organizational factors, and vival (Dess & Beard, 1984). In addition to the

individual resources. Second, we examine the SE perspectives associated with traditional organiza

related actions or processes in the firm, specifically tional theories such as ecological theory (Hannan

focusing on the orchestration of its resources and & Freeman, 1984, 1989) and evolutionary theory

the entrepreneurial actions that are used to pro (Winter, 2005), an entrepreneurial perspective of

tect and exploit current resources while simulta this relationship proposes that an organization

neously exploring for new resources with value and those within it influence the environment

creating potential. These actions occur primarily (Smith & Cao, 2007). Munificence, dynamism

at the firm level. Last, we examine outcomes, (and the uncertainty resulting from it), and inter

which vary across levels. Specifically, we focus on connectedness are important environmental fac

the creation of value for society, organizations, tors for SE.

and individuals. These benefits include societal

Environmental munificence facilitates acquir

enhancements, wealth, knowledge, and opportuing resources and identifying opportunities as well

nity. First, we discuss the inputs of the extended

as the ability to exploit the resources and oppor

SE model.

tunities to create competitive advantage. Organi

zations seek out environmental munificence,

Inputs: Resources/Factors

which refers to the level of resources in a partic

Environmental Factors

ular environment that can support sustained

The firm's external environment affects its abilitygrowth, stability, and survival (Dess &. Beard,

and the ability of individuals to discover or create 1984). Munificence allows firms to acquire re

opportunities and, subsequently, their ability tosources such as raw materials, financial capital,

exploit those opportunities as a foundation for labor, and customers (Aldrich, 1979; Castrogio

competitive success. The relationship between the vanni, 1991) and intangible assets such as an

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 61

industry's or geographic region's tacit knowledge identifying and exploiting new opportunities).

(Agarwal, Audretsch, &. Sarkar, 2007). However, research has shown that environmental

The munificence of an environment (e.g., geo dynamism has a positive relationship with new

graphic region) is context-specific for the firm. venture creation (Aldrich, 2000) and innovation

Moreover, entrepreneurially minded individuals through the stimulation of exploration (Wang <St

gain access to resources in the environment to Li, 2008).

generate competitive advantage and create value Gaglio and Katz (2001) suggest that individuals

by engaging in entrepreneurial bricolage. Baker who act entrepreneurially seek opportunities in

and Nelson (2005) identified three characteristics dynamic markets, using their knowledge stocks

that affect how perceptions of resources influence and ability to perceive and deal with uncertainty.

the successful interaction between a firm and its The ability to operate under conditions of uncer

environment. First, firms are idiosyncratic in what tainty may also be based on an individual's moti

they perceive to be value-creating resources. Sec vation and risk propensity (Baum & Locke, 2004).

ond, firms tend to gain differential benefits from Alternatively, radical innovations produced by

resources based on their leaders' creative judg entrepreneurial firms often serve as a catalyst for

ments and actions. Third, because of the nature of or at least contribute to more dynamic and poten

the first two attributes, firms can capitalize on tially more munificent environments.

resources that other organizations deem to have In dynamic environments, some firms use rela

less value-creating potential. Thus, even resource tionships to gain access to needed resources from

constrained environments can be perceived as partners and then bundle them to exploit oppor

munificent by some firms. An example is the tunities. In addition, firms may use cooperative

intangible assets that leak into the environment strategies such as alliances to build capabilities

when firms fail to commercialize knowledge they that facilitate the building of a competitive ad

hold (Agarwal et al., 2007). As knowledge is vantage. Theories of interconnectedness includ

rarely idiosyncratic to one organization, it is diffi ing networks and social capital explain the paths

cult to avoid leakage and protect against appro firms follow to build capabilities in this manner.

priation by competitors. This knowledge spillover Building on organizational learning, resource

allows individuals and firms to appropriate knowl based, and real options theories, Ketchen et al.

edge that can be used to create firm capabilities. (2007) argued that collaborative innovation, in

These capabilities are then used to gain a compet which large and small firms share ideas, knowl

itive advantage that subsequently leads to perfor edge, expertise, and opportunities, supports SE.

mance gains (DeCarolis & Deeds, 1999; Grant, Small firms are able to use creativity to create

1996), resulting in the economic growth of a unique innovation while minimizing the liabilities

region and the expansion of an industry (Agarwal associated with their small size and newness. Al

et al., 2007). ternatively, because of slack resources, large firms

The environment many firms face is inherently are able to explore opportunities outside their

dynamic, thereby producing uncertainty (Barnard, traditional domain and leverage existing business

1938). Uncertainty (and the willingness to bear practices in doing so.

uncertainty) (McMullen &. Shepherd, 2006) si

Organizational Resources

multaneously poses threats and reveals opportuni

ties. Because of uncertainty, the quality of infor Culture and top leadership are perhaps the re

mation available to firms and individuals is sources that are the most idiosyncratic to a specific

organization.

limited, reducing their ability to assess present and Effective leadership is required to

future environmental states. In addition,develop

an in and grow new ventures and to entrepre

ability to access robust information aboutneurially

condi lead established corporations. Leaders

tions in the external environment creates ambi understand the importance of developing and sup

guity during the strategic decision-making process

porting a culture through which the entrepreneur

ial actions necessary to achieve profitable growth

(e.g., decision makers lack adequate knowledge for

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

62 Academy of Management Perspectives May

are established (Kuratko,

cessIreland, Covin,

additional resources &.

and to build and Horns

leverage

capabilities to achieve

by, 2005). "[An] entrepreneurial a competitive

culture is advantage

one in

(Hitt, Lee, &. Yucel,

which new ideas and creativity are2002). Thus, specific social

expected, risk

skills influence

taking is encouraged, failure individuals' ability not

is tolerated, only to

learning

acquire knowledge

is promoted, product, process and and resources, but to create

administrative

innovations are championed, and continuous

and/or identify opportunities. Baron and Mark

man (2000, 2003)

change is viewed as a conveyor ofsuggest that social skills—for

opportunities"

(Ireland et al., 2003, p. example,

970). reputation

Thus,and expansion of social

entrepreneur

networks—play

ial leadership is the ability a significant roleothers

to influence in the successto

emphasize opportunity-seeking and

of individuals and their advantage

new ventures by attract

seeking behaviors (Covin & Slevin,

ing resources 2002).

such as financial capital and key

Entrepreneurial leaders employees.

create visionary scenar

ios that can be used to assemble and mobilize a In a specific context, evidence indicates that

supporting group in the firm that is committed toan entrepreneur's social skills and social networks

opportunity discovery and exploitation (Gupta,influence outcomes for both new ventures and

Macmillan, &. Surie, 2004). The leader and the established organizations (Baron & Tang, 2009;

organizational culture are interdependent; theyBatjargal et al., 2009). Additional evidence indi

are symbiotic, with the leader's judgments affect cates that within the firm, individuals with well

ing the organizational culture and cultural attrideveloped social skills who recognize or create

butes influencing a leader's future decisions andopportunities can gain acceptance for projects

actions. In this manner, an "entrepreneurial loop" that require cross-divisional resources through so

occurs between a leader's ability to identify an cial networks (Kleinbaum & Tushman, 2007).

opportunity and the attributes of organizational Actions taken to exploit an opportunity encour

culture that positively influence pursuing itage others in the organization to collaborate,

(Shepherd, Patzelt, &. Haynie, 2009). which in turn facilitates a social structure and

culture conducive to subsequent opportunity

Individual Resources

seeking behaviors.

Financial capital (a tangible resource) and social Human capital is the set of individuals' capa

and human capital (intangible resources) are necbilities, knowledge, and experience related to a task

essary to engage in SE (Ireland et al., 2003). and the ability to increase the "capital" through

Alone, financial capital is relatively less important learning (Dess &. Lumpkin, 2001). Chandler

than social and human capital for achieving, and(1962) wrote that of all resources available to

especially for sustaining, a competitive advantage;firms, human resources are perhaps the most im

however, financial capital is often crucial for acportant; thus, idiosyncratic human capital can be

quiring or creating the resources necessary to ex central to a new venture's survival (Baker, Miner,

ploit opportunities. For example, new ventures Easley, 2003) and an established firm's success.

and firms with stronger financial positions in earlyTacit knowledge is particularly important in iden

developmental stages are more likely to survive,tifying entrepreneurial opportunities (McGrath &

grow, and experience higher performance (ChadMacMillan, 2000) and in achieving a competitive

dad &. Reuer, 2009). In addition, established firms advantage (Coff, 2002). Individuals' knowledge,

with strong financial resources have slack, which skills, and abilities, along with their motivation

can facilitate the development of innovations and passion to perform, are important for a firm to

(Kim, Kim, &. Lee, 2008). exploit an opportunity and achieve an advantage

The firm's social capital is the sum of its inter as the sources of its long-term success.

nal social capital (relationships between individ The entrepreneurial mindset, composed of

uals) and its external social capital (relationshipsalertness, real option reasoning, and opportunity

between external organizations and individuals in recognition, facilitates rapid sensing to identify

the focal firm). It facilitates actions taken to acand exploit opportunities, even those that are

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 63

highly uncertain (McGrath & MacMillan, 2000). as unconventional risk taking, focused intensity,

Entrepreneurial alertness entails the ability to no and belief in a dream (Cardon, Wincent, Singh,

tice opportunities that have been hitherto over &. Drnovsek, 2009). Entrepreneurial leaders' ex

looked and to do so without searching for them pression of passion for the new venture can moti

(Kirzner, 1979). However, being alert is a neces vate employees to create new ideas, take risks, and

sary but insufficient condition to effectively en develop personal pride in the firm's goals. There

gaging in SE. In the SE framework, an individual fore, passion contributes to entrepreneurial suc

must respond to numerous economic changes and cess because of the commitment and effort gener

innovations in a dynamic (and uncertain) envi ated (Baum & Locke, 2004). Passion and the

ronment. To make decisions, one needs a frame commitment it engenders contribute to entrepre

work that helps to identify decision criteria, the neurial self-efficacy. Cassar and Freidman (2009)

available resources, and the value creation goals found that entrepreneurial self-efficacy has a sig

(Gaglio, 2004). Entrepreneurial cognition, or the nificant influence on the commitment of both

knowledge structures driving assessments of op personal time and capital to discover (or create)

portunities (Holcomb, Ireland, Holmes, & Hitt, and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities. For en

2009), helps to differentiate the degree of risk trepreneurial leaders, high self-efficacy often con

involved with various opportunities (Baron, 2007) tributes to enhanced revenue and employment

and thus to select the most appropriate one for the growth in the firm (Baum & Locke, 2004). Pas

new venture (or established organization). sion and entrepreneurial self-efficacy motivate en

Real options logic suggests that real assets pos trepreneurs to pursue and realize strategic and

sess the same characteristics as financial options entrepreneurial goals that are central to SE.

(Barney, 2002). This set of characteristics facili Alvarez and Barney (2007) argued that there

tates individuals' willingness to engage in risky are two theories of entrepreneurial action: discov

(yet carefully evaluated) entrepreneurial activity ery of existing opportunities and creation of new

through opportunity-seeking behavior. Real op opportunities. Thus, opportunity-seeking behav

tions have the potential to positively or negatively ior could involve being alert to existing opportu

influence opportunity- and advantage-seeking be nities or creating new opportunities. The tradi

haviors. The nature of factors in the external

tional perspective of the entrepreneurship process,

environment at a point in time (e.g., bankruptcy

focused on the discovery of an opportunity (Eck

hard & Shane, 2003), relies on a notion of cau

laws) determines the maximum potential down

sation. Two individuals may have the same char

side loss associated with a firm's risky investments,

while the upside potential of these investments acteristics

is and resources; however, environmental

commonly high. An entrepreneur-friendly bank

variation may lead only one of the two to identify

ruptcy law (i.e., one that allows reasonable

and exploit a particular opportunity (Alvarez &

conditions for continuing the new ventureBarney,

by 2010). Identifying existing opportunities

allowing the restructuring of debt) encouragesrequires

en the entrepreneurial mindset.

trepreneurial activity and economic developmentHowever, creating opportunities involves dif

(Lee, Peng, & Barney, 2007). Alternatively, ferent types of entrepreneurial actions: effectua

strong bankruptcy laws (e.g., ones that make tion

it and creativity. Effectuation is based on the

difficult to continue the new venture after declar

notion that firm growth relies on dynamic and

ing bankruptcy) deter individual and firm riskinteractive judgments in which the future is un

taking behaviors. predictable yet controllable through human ac

Goal setting is significantly influenced by an and the belief that the environment can be

tion,

enacted through choice (Sarasvathy, 2008). Thus,

individual's psychological factors. For example,

passion, which in an entrepreneurial contextcognitive

is ability to effectuate is used to create

reflected in the entrepreneur's devotion andopportunities

en in the environment and to achieve

thusiasm for a proposed business venture (Chen,short-term competitive advantages. Creativity af

fects the quality and quantity of innovations,

Yoa, &. Kotha, 2009), accounts for behaviors such

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

64 Academy of Management Perspectives May

strategy, or an entrepreneurial

shaping both existing capabilities strategy. Impor

for competitive

tantly, although each

advantage and entrepreneurial action and related subpro (Ire

opportunities

land et al., 2003). Creativity

cesses are useful,in heterogeneous

properly synchronizing the re

teams or organizations source orchestration actions

generally positively influences

produces at least

the realized outcomes.otherwise uncon

two outcomes. By connecting

An emerging

nected individuals, creative ideasbody ofare

empirical

moreevidence easily

sup

translated into products ports

(Obstfeld,

resource orchestration's2005),

validity asand

a meanscre

ative approaches may of be more

managing a firm's easily accepted

resources to gain maximum

(Shalley & Perry-Smith, value from2008). Acceptance

them. For example, Ndofor, Sirmon, of

creative approaches, in and He's (2011)

turn, results showed

fosters an thatentrepre

managerial

neurial culture in the firm and construction of actions mediate the resource/performance linkage.

market niches in the environment over time. These findings suggest the importance of the lead

Next, we describe the processes component of er's role in realizing the full potential from a firm's

the SE model. resources. In support, Sirmon, Gove, and Hitt

(2008) showed not only that leaders' context

Resource Orchestration Processes

specific resource bundling and deployment actions

Research indicates that competitive advantage re affect performance, but that the importance of

sults from controlling valuable and rare resources.their actions increases as rivals' resource portfolios

Yet, while control of such resources is necessary approach parity. However, leaders' actions must

for competitive advantage, leaders must take furbe comprehensive in synchronizing the various

ther actions for the advantages to be developed resource orchestration actions (Sirmon & Hitt,

and exploited and hopefully sustained over time 2009) while simultaneously addressing both capa

(Crook, Ketchen, Combs, & Todd, 2008; Grimm,bility strengths and weaknesses to realize compet

Lee, & Smith, 2006). Resource orchestration, anitive advantages that help them pursue future op

emerging stream of work that is grounded in re portunities (Sirmon, Hitt, Arregle, & Campbell,

source-based theory (RBT) and dynamic capabil2010).

ities literature, focuses attention on these actions Next, we discuss each major resource orches

(Sirmon, Hitt, Ireland, & Gilbert, 2011). Retration action within a strategic entrepreneurship

source orchestration is based primarily on the concontext.

ceptual work of Sirmon et al. (2007) and Helfat et

al. (2007). Structuring

Resource orchestration is concerned with the Among the three subprocesses of structuring

actions leaders take to facilitate efforts to effecquiring resources is arguably the most impor

tively manage the firm's resources. Primary among for young firms. Young firms often operate

these are actions to structure the firm's resource resource disadvantage (Mosakowski, 2002)

portfolio, bundle resources into capabilities, and must work to overcome it. Research indicates

leverage the capabilities to create value for cus the entrepreneur's "story" strongly affects y

tomers, thereby achieving a competitive advan firms' acquisitions of resources (Gartner, 2

tage for the firm. More specifically, structuring Martens, Jennings, and Jennings (2007) prov

includes acquiring, accumulating, and divesting evidence that capital infusion increases wh

resources; bundling involves stabilizing existing entrepreneur's narrative offers prospective i

capabilities, enriching current capabilities, and pi tors 1) an identity for the firm, 2) logic as to

oneering new capabilities. Leveraging requires a the firm will exploit its opportunity, and 3) i

sequence of actions including mobilizing capabil mation indicating how the firm's intended ac

ities to form requisite capability configurations, are appropriate for its current environment.

coordinating the integrated capability configura over, they concluded that an effective narra

tions, and deploying these configurations with a has significant influence, such that a chan

resource advantage strategy, a market opportunity narrative quality (what they termed a "un

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 65

change") increased investment by millions of dol Leveraging

lars. Beyond capital investment, Zott and Huy Leveraging actions move the firm from the poten

(2007) found that entrepreneurs' "symbolic ac tial to create value to realizing value by deploying

tions" speak loudly to a wide array of resource the capabilities to achieve competitive advan

providers. More specifically, they found that dem

tages. Leaders mobilize, coordinate, and deploy

onstrating personal credibility, professional orga

specific capabilities in particular market contexts

nization, achievement, and relational aptitude not

by choosing and implementing a particular strat

only resulted in higher levels of capital invest

egy. Of equal importance to choosing the strategy

ment, but also helped entrepreneurs attract tal

to follow is synchronizing the actions necessary for

ented human capital and assemble a sufficient

leveraging. Recent empirical work demonstrates

customer base.

that resource investment deviating from industry

Firms may also find it necessary to build re

norms negatively affects performance, unless that

sources internally (accumulate) as well as divest

deviation is synchronized with an appropriate le

them. Divestment is an understudied phenome

veraging strategy (Sirmon & Hitt, 2009). When

non; however, it is critical in managing resources.

matched to the appropriate strategy, greater in

Recent research indicates that reducing weak

vestment deviations (in either direction from in

nesses may be more important for increasing per

vestment norms) lead to higher performance. Sup

formance than increasing a firm's strengths (Sir

porting these conclusions, Holcomb, Holmes, and

mon et al., 2010). In addition, Morrow, Sirmon,

Connelly's (2009) results showed that synchroni

Hitt, and Holcomb (2007) provided evidence that

zation across the resource management processes

divestment can be especially useful when firms

is vital to developing a competitive advantage.

attempt to recover from a performance crisis. Pre

For synchronization to occur, leaders require

sumably, the divested resources create a weakness

sufficient information pertaining to the firm's ex

that when released removes a negative influence

ternal environment and internal organization as

on firm performance (Shimizu & Hitt, 2005).

well as the ability to effectively process that in

Accumulating resources (knowledge, skills, repu

formation. Sleptsov and Anand's (2008) research

tation, etc.) often complements acquiring re

suggested that having one without the other,

sources, thereby allowing firms to create unique

or—as is more likely the case—when such infor

resource portfolios.

mation is not balanced, performance is negatively

affected. Thus, feedback loops exist among struc

Bundling turing, bundling, and leveraging actions (Sirmon

Bundling resources to form capabilities requires et al., 2007). Although we discuss these actions

intentional actions. Often, capabilities are formed sequentially, in practice leaders can, and likely do,

within functions such as manufacturing and mar perform them in an iterative process.

keting. Bundling requires knowledge while pro The choice of sequencing or iteration among

viding a rich learning context, especially tacit these actions may be based on the specific oppor

learning. For example, Kor and Leblebici (2005) tunity being considered. For instance, Choi and

found that bundling senior partners with less ex Shepherd (2004) found that the decision to ex

perienced associates in law firms positively affects ploit an opportunity was influenced by several

performance. These results support Hitt, Bierman, factors, including knowledge of the customer,

Shimizu, and Kochhar's (2001) suggestion that knowledge of the underlying technology offered,

bundling choices strongly affect the development level of stakeholder support, and overall manage

of tacit knowledge. Thus, the choices leaders rial experience. Moreover, an opportunity's at

make regarding the bundling of resources to sta tractiveness enhanced the effect of all of these

bilize, enrich, or pioneer new capabilities are im factors, especially managerial experience. Thus,

portant to achieving and sustaining a competitive when potential entrepreneurs have a high level of

advantage (Lu, Zhou, Bruton, & Li, 2010). stakeholder support that addresses much of their

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66 Academy of Management Perspectives May

turing they

resource acquisition concerns, his initial

may be relationsh

more

development

likely to begin the resource successfully

orchestration se

his actions.

quence with structuring critical personal compl

On the other

vatorknowledge

hand, an entrepreneur with and knowledge

aboutof

custhe

tomer needs may be more thelikely

relationship from

to begin with cont

a

tive with substantial equity

leveraging strategy and follow it with the bundling

and structuring actions him to appropriate

necessary nearly

to implement

the strategy. value he helped to create.

Thus, regardless of the m

Value Creation and Appropriation

copyrights, or negotiated

tion successfully

Regardless of the sequence, of intellectual propert

exploiting

an opportunity invitesresources

imitation is from competi

critical to the

that

tors. Several factors such as resource orchestration

causal ambiguity and

time diseconomies (Dierickx

cuss the&outcomes

Cool, 1989)

thatcan

resu

prevent or slow imitation; however, more proac

entrepreneurship.

tive actions can also discourage imitation. Copy

Outputs

rights and patent protection areof twoStrategic important Entrep

The use

barriers entrepreneurs can processes

to protect and or actions

fore

erate several

stall others from appropriating value from their potential out

ideas and resources (Burgelman

ultimate outcome & Hitt, is 2007).either In f

firm or achieving

fact, research in value appropriation competiti

and intellec

tual property protection value for customers

is growing rapidly, of an e

espe

time both of these outcomes

cially because policy and competitive changes in are intended to cre

the 1980s led to "patentate value for those (Ziedonis,

races" holding equity in the2004).

firm.

Research indicates that a firm's

Creating patenting

wealth for owners strat

is typically interpreted

as "financial

egies contribute several importantwealth," whichoutcomes

is a primary goal. to

entrepreneurship, including

However, owners/entrepreneurs

alliance partner may also achieve

selec

other forms

tion (Lavie, 2007) and IPO of wealth, such as "socioemotional

underpricing (Heeley,

Matusik, &. Jain, 2007),wealth"

among (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez-Mejia,

others. Even & Larraza

more

important, CeccagnoliKintana,

(2009) 2010) and

provided

personal happiness.

evidence

Yet we

also expect the outcome(s)

that patent protection increases a firm's of SE toability

benefit soci to

appropriate rents from innovation.

ety. Importantly, Moreover,

increasing the wealth of owners

nonconventional patenting strategies

should contribute such

positively to additional eco as

"preemptive patenting" can (e.g.,

nomic activity generate market

job creation, technological

power for firms that are following

advancement, such

and economic stabilitystrategies

and growth)

to avoid legal battles and other

and thereby "hold-up"

benefit society, con

and there is potential

for other social benefits

cerns that may be present in technologically in as well. To achieve these

tense industries (Ziedonis, 2004).

longer term and major outcomes, several interim

For the nascent firm or entrepreneur,

outcomes are likely to be critical, patenting

such as creating

is not the only means tonew protect intellectual

technologies or developing prop

innovations with

erty. Coff (2011) described how

value-creating Tony

potential. Fadell,

In addition, the

an interim

driver behind Apple's iPod, protected

and critically important outcomehisis interests

achieving a

when negotiating his employment relationship

competitive advantage. In fact, long-term survival

with Apple. Fadell first istried toa firm

unlikely for create what

that is unable was

to achieve at to

become the iPod within

least his previous

competitive employer,

parity. Innovation often con

Philips Electronics, and tributes

then to within his own

a competitive advantage, failed

but there are

venture before joining Apple.

other Fadell

activities necessary was able

to achieving such an to

protect the assets he brought to Apple

advantage (e.g., managing resourcesby

wiselystruc

and

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 67

effectively as described in the previous section). advantage. The latter actions (incremental inno

Below, we discuss several of these outcomes. vation and imitation by competitors) tend to

move the market toward equilibrium (Kirzner,

Individual Benefits

1973).

Individual entrepreneurs gain value when engag To create a novel product often requires cre

ing in strategic entrepreneurship. For example, ativity and entrepreneurial approaches (Ward,

they gain satisfaction in developing an indepen 2004)- In fact, Ward (2004) suggested that suc

dent business and creating value for customers. In cessful new ideas frequently achieve an effective

addition, increases to the entrepreneur's financial balance between novelty and attributes that are

wealth result from venture success. Thus, starting familiar but attractive to customers. Creating

a new venture and operating it successfully likely novel (radical) innovation often requires a signif

satisfies several of the entrepreneur's needs, in icant investment of time, effort, and frequently

cluding self-actualization. financial capital as well. To produce novel inno

Individual entrepreneurs also learn when they vations, firms often must shift their focus from

develop and implement a new venture; as a result, current products to future technologies and prod

they build their personal knowledge stocks. Baron ucts (Sood & Tellis, 2005). Because firms rarely

and Henry (2010) argued that enhanced cognitive have the resources needed to achieve this type of

resources, which entrepreneurs acquire through innovation internally, they frequently search ex

sustained deliberate practice, strongly influence ternal sources to locate them. To do so, they may

the success of their subsequent ventures. Accord need to develop networks of partners that provide

ing to Baron and Henry, deliberate practice en inputs to help develop the innovations (Hughes,

tails intense, persistent, and highly focused efforts Morgan, & Ireland, 2010), requiring them to be

to improve current performance. In taking these come highly proficient at managing innovation

actions, entrepreneurs' knowledge stocks and networks (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006). Frequently,

other cognitive resources (e.g., perceptual acuity, new venture firms are more creative and thus can

memory) are enhanced, helping them to more develop more novel innovations, while estab

accurately recognize, evaluate, and exploit busi lished firms are effective in adding new features to

ness opportunities. This process can also apply to and improving their current products to maintain

entrepreneurial leaders in established firms. an advantage in the market. Therefore, partner

ships between new venture firms and larger estab

Organizational Benefits: Technology and Innovation lished firms can be productive because of the

Creating new technology and innovation is cru complementary capabilities held by each. In this

cial for many firms, regardless of their size or age. way, the partnership helps the firms balance ex

Of course, for a new entrepreneurial firm, it may ploration and exploitation.

be critical to break into an established market or Following a recent trend, many firms are build

to create a new market, developing a product that ing relationships with university technology de

is highly differentiated from existing products and velopment programs as an external source for new

one that creates substantial value for customers. technologies and products. Simultaneously, an in

Often, this new product will be based on a highly creasing number of universities have built tech

novel, or what is sometimes referred to as a radi nology transfer programs in which they develop

cal, innovation. In fact, the disequilibrium to new technologies and transfer them to the private

which Schumpeter (1942) referred requires a sector for commercialization. As such, the univer

novel innovation. Yet after firms have captured a sity becomes a source of R&D for these businesses

market-leading position with an innovative prod (Markman, Phan, Balkin, <St Gianiodis, 2005). In

uct, they often then try to incrementally improve these cases, the university generally is paid an

that product in order to stay ahead of competitors initial fee for the technology and/or retains a

that are trying to imitate and improve the product percentage ownership in the technology/product.

to gain competitive parity or, ideally, competitive Finally, some firms use acquisitions to gain

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

68 Academy of Management Perspectives May

access to new technologies and

Lumpkin, new

2009; Zahra, highly

Rawhouser, valu

Bhawe, Neu

able innovations (Makri,baum, &Hitt, &Essentially,

Hay ton, 2008). Lane, social2010).

entre

Such acquisitions are common inorganizations

preneurs establish the pharmaceu

to meet social

tical industry and in other high-technology

needs in indus

ways that improve the quality of life and

tries such as software development. Acquisitions

increase human development over time (Zahra et

al., a

are regularly practiced by 2008) while benefitingof

number owners in ways that

technology

continue

oriented firms, including revenue flow and allow

Microsoft andthem Cisco,

to earn a

with the intent of gaining access

return to new

on their investment. software

Organizations created

ideas and technologies. to engage in social entrepreneurship—and, more

Firms seeking to developbroadly,new technologies

corporations engaging in socially respon

sible actions—serve

must currently hold, develop, or have a variety

accessof stakeholders.

to the

necessary and relevant scientific knowledge.

Stakeholders represent a broader view ofSci those

ence or scientific knowledge

affectedprovides the

by an organization (notbase

limited for

to own

developing and commercializing new technology

ership). Thus, stakeholder theory supports much

of this

(Makri et al., 2010). The research concerned

recent with social entre

emphasis on

nanotechnologies is a prime example

preneurship of

(Mahoney, 2010; highly

Surroca, Tribo, &

Waddock, 2010).

popular and potentially valuable work that repre

sents strategic entrepreneurial activity

Yet beyond the in many

specific entrepreneurial activi

industrial and service sectors (Woolley

ties designed &. social

to serve certain Rottner,

needs, in line

2008). An additional benefit

with SE andof developing

stakeholder theory, broadernewperspec

technologies and innovation is

tives can be the to

employed creation of of

achieve other types

new knowledge, which in outcomes,

turn such frequently provides

as attempts to create new compa

new market opportunities (to

nies that introduce

enrich a new

the natural environment and/or

product and even to create a new

are designed market)

to overcome even

or limit others' negative

across industries (Woolley, 2010). Such innova

influences on the physical environment. For ex

tion or technology and ample,

theentrepreneurial

additional effortsvaluable

to harness wind

knowledge spillover from developing the technol

power could have major long-term benefits to

ogy and/or innovation contribute to aaclean

society by providing competitive

energy source (Sine &

advantage. Lee, 2009). In addition, novel innovations could

be used to address a number of environmental

Societal Benefits

problems (Adner &. Kapoor, 2010). Many firms

Certainly, increasing owners' wealth can have may take actions to reduce the negative influences

positive societal benefits because it injects more their operations typically have on the environ

financial capital into the economy and thereby ment with the hope of creating a positive greening

promotes economic growth (Agarwal et al., 2007). effect (Delmas & Montes-Sancho, 2010).

Indeed, many have argued that entrepreneurial Some have argued that entrepreneurial activi

activity is a major contributor to economic devel ties targeting areas of social need could lead to a

opment and growth, creating new jobs and en marketization of nonprofit organizations in ways

hanced market valuations (Baumol &. Strom, that do not truly satisfy societal needs (Eikenberry

2007). Yet entrepreneurial activity can provide & Kluver, 2004). Although this concern is not

other benefits to society as well. without foundation and marketization could have

A new area of research referred to as social negative outcomes, there are a number of positive

entrepreneurship examines how entrepreneurs de examples of entrepreneurial efforts that provide

velop enterprises with the intent of helping soci major benefits to society, often substantially ex

etal members, often those who are underprivileged ceeding public organizations' capabilities to satisfy

and have low incomes (Kistruck, Webb, Ireland, the needs (Hitt, 2005). For example, the KIPP

& Sutter, 2011). This focus has become a signif (Knowledge Is Power Program) charter schools

icant and growing research area (Short, Moss, & demonstrate how entrepreneurial efforts can gen

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 69

erate significant benefits for society that exceed operate internationally, the necessity of making

the benefits created by public educational organi ethical decisions, and the importance of recogniz

zations, providing education from prekindergarten ing the criticality of consumers for successful strat

through 12th grade. The organization uses a num egies influence the decisions and actions the firm

ber of motivational tactics and largely serves takes to form and exploit competitive advantages.

children from underprivileged families. It has Entrepreneurship is concerned with recogniz

produced phenomenal results. The educational ing opportunities that when effectively exploited

program offered is one of intense communal focus through the firm's competitive advantages lead to

on specific goals, and the intent is to effectively enhanced value and wealth. Opportunities to pro

prepare and encourage students to attend college duce innovative goods and services that create

after they graduate. In fact, 85% of those gradu value for customers often are a product of market

ating from KIPP schools enter college—compared imperfections. Because competitors will eventu

with approximately 40% of low-income students ally determine how to imitate a firm's value-cre

nationally who enter college after graduating from ating competitive advantages, continuous innova

high school (Peterson, 2010). tion is the source of sustained value and wealth

Entrepreneurial activity can also have other creation over time.

societal benefits. For example, an enhanced focus Strategic entrepreneurship allows the firm to

on and resources allocated to entrepreneurial ac apply its knowledge and capabilities in the current

tivity could increase the opportunities for women environmental context while exploring for oppor

to pursue entrepreneurial undertakings. In fact, if tunities to exploit in the future by applying new

the limitations are loosened and barriers to engag knowledge and new and/or enhanced capabilities.

ing in entrepreneurial activity for women and To be effective, SE demands that firms achieve a

other disadvantaged groups are overcome, the re balance between the opportunity-seeking behav

sulting growth in entrepreneurial activity could iors of "entrepreneurship" and the advantage

eventually facilitate positive societal change by seeking behaviors associated with "strategic man

empowering more women and individuals from agement." To a degree, the entrepreneurship part

underprivileged families to become entrepreneurs of SE requires flexibility and novelty, while the

and to gain access to the economic benefits that strategic management part seeks stability and pre

flow from successful entrepreneurial activities dictability. However, achieving this balance is

(Calas, Smircich, & Bourne, 2009). Thus, overall, challenging because firms have finite resources,

entrepreneurial activity can help to build new meaning that trade-offs often must be made re

economic, social, institutional, and cultural envi garding the amount of resources allocated to ex

ronments and thereby provide significant benefits ploiting current competitive advantages and those

to society (Rindova et al., 2009). allocated to exploring for opportunities and new

sources of advantage for the future. Achieving this

Discussion and Conclusions balance requires an organizational structure capa

ble of supporting the twin needs of exploitation

ments that have become increasingly common and exploration. Future research should seek to

Theproduce

dynamic and complex

multiple challenges competitive environ

for firms seeking clearly specify the characteristics of such a struc

to create value and wealth. Uncertainty and am ture. This type of structure likely needs the attri

biguity are but two of the outcomes in the current butes of an ambidextrous organization that allow

business environment. Strategic management it to simultaneously explore and exploit (Benner

and entrepreneurship are organizational processes &. Tushman, 2003). The most effective balance

firms use to reduce and/or take advantage of un between exploring and exploiting may be partially

certainty and ambiguity and create more value dependent on the type of competitive environ

and wealth. In essence, the intent of strategic ment in which the firm exists. Future research

management is to develop and successfully exploit should examine the extent to which the compet

competitive advantages. Increasingly, the need to itive environment moderates the relationship be

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

70 Academy of Management Perspectives May

tween the balance achieved

bothbetween exploitation

advantage- and opport

and exploration and the iors

firm's ability

within to create

a single organiz

value over time. what actions are required for

To be sustained over time, even nonprofit

and especially sustain en a com

trepreneurial ventures such as KIPP must

As described herein, SE is a develop

and maintain a competitive advantage.

in which resources For may exam exist

ple, if KIPP charter schools were not better

at the individual, organizatio than

their public counterparts,The

they would be unable

organization bundles to th

sustain their activity. Ifcapabilities

they provide and no thenviable levera

value for

benefits to customers beyond what customers

competitors (Sirmo

provide, they are unlikely outcomes

to survive. of these activities c

Likewise,

large established firms often have slack

individuals resources

(entrepreneurs,

that have accrued fromtional successful

employees, operationscustomers,

and society.

across time. Yet if these large organizations Yet very fail to little

engage in opportunity-seeking

crosses behaviors,

these levels. an Most

en e

trepreneurial firm (or asearch focusescompetitor

large on either the individualacting

or the

organizational level.

entrepreneurially) will introduce More research

a better is needed to

product

that provides more value understand the influence of the interaction

to customers and take of

their market away. Theindividual

demise of Polaroid

and organizational attributes was

on en

accelerated by new competitors' introduction

trepreneurial activities and outcomes. In addi of

tion,

digital cameras. Similarly, thewe need to understand

unique when and under

approach to

video rental introducedwhat by Netflix

conditions eventually

the benefits at any one level

drove Blockbuster into bankruptcy.

become dominant motivators of entrepreneurial

Therefore, SE is relevant across the full life

activities.

Another area

cycle of organizations, although warranting more research

historically, stra con

tegic management has largely been associated

cerns the effects of societal-level institutions on

with mature organizationsentrepreneurial activities and outcomes. For ex

and entrepreneurship

largely associated with young

ample, how ventures. As such,

do informal institutions (e.g., a soci

SE implies a long-term view of value

ety's norms, creation

values, and that

beliefs that determine the

results from simultaneously engaging

social acceptability in and

of actions opportu

their outcomes)

nity- and advantage-seeking behaviors. Because oflaws)

and formal institutions (e.g., regulations and

this, the concept of SE poses

affect a numberactivity?

entrepreneurial of temporal

Evidence suggests,

research questions. For example, there

for example, that is a need

the institutions to

associated with

conduct longitudinal research of new ventures as

bottom-of-the-pyramid (BOP) markets1 are char

they mature to understand how

acterized by the

three key nature

factors: of

(1) underdeveloped

entrepreneurial activities varies

formal over

institutions, time. differences

(2) significant How

between the formal

do organizations learn to manage and informal

resources in institutional

ways

that appropriately and simultaneously serve

boundaries in BOP markets theirmar

and in developed

kets, and (3) differences

need to exploit today's advantages or variancesfor

and explore in formal

and informal institutions within individual BOP

new opportunities to exploit?

Supporting this type of work

markets is et

(Kistruck research

al., 2011). to

precisely detail and classify advantage-seeking be

How do underdeveloped formal institutions

haviors and opportunity-seeking

(in the form ofbehaviors

poorly developed used

propertyin

rights

organizations. To what degree do these behaviors

laws and inadequate enforcement of contracts,

overlap and to what extent

among are theyaffect

other factors) complemen

entrepreneurs' deci

tary? What methods should firms use to master

both types of behaviors? Is it possible for individ

1 Impoverished in nature, a BOP market is one in which the average

ual business units and departments

wage earned is less than $2 per day to excel

(Prahalad, 2004). at

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hitt, Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 71

sions to establish ventures? What effect does the References

variance in different societies' norms, values, Adner, R., &. Kapoor, R. (2010). Value creation in innova

and beliefs have on a firm's ability to identify tion ecosystems: How the structure of technological in

and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities? How terdependence affects firm performance in new technol

ogy generations. Strategic Management Journal, 31(3),

do formal and informal institutions influence 306-333.

the importance and use of social networks by Agarwal, R., Audretsch, D., & Sarkar, M. B. (2007). The

entrepreneurs? Essentially, more research is process of creative construction: Knowledge spillovers,

needed to understand how country-level formal entrepreneurship and economic growth. Strategic Entre

preneurship Journal, 1(2), 263-286.

institutions and societal culture affect entrepreAldrich, H. E. (1979). Organizations and environments.

neurial activities. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

In addition, do the effects of formal and inforAldrich, H. (2000). Organizations evolving. Beverly Hills,

CA: Sage.

mal institutions on entrepreneurial activities vary

Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and

between the formal economy and those in the creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action.

informal economy, where the formal economy in Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1), 11-26.

cludes activities that are deemed legal by formal Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2010). Entrepreneurship

and epistemology: The philosophical underpinnings of

institutions and legitimate by informal institu the study of entrepreneurial opportunities. Academy of

tions (Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland, &. Sirmon, 2009)? Management Annals, 4, 557-583.

Examining the effects of the boundaries estab Andrews, K. R. (1971). The concept of corporate strategy.

Homewood, IL: Irwin.

lished by formal and informal institutions within

Baker, T., Miner, A. S., & Easley, D. (2003). Improvising

the context of formal and informal economies

firms: Bricolage, retrospective interpretation and impro

suggests a robust array of research questions con visational competencies in the founding process. Re

cerning SE. For example, does SE create more or search Policy, 32(2), 255-276.

Baker, T., & Nelson, R. (2005). Creating something from

less value when used by firms competing in an

nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial

informal economy compared to firms operating inbricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329—

the formal economy? 366.

The SE construct encompasses an array Bamford,

of C. E. (2005). Creating value. In M. A. Hitt &

R. D. Ireland (Eds.), The Blackwell encyclopedia of

knowledge stocks. It draws on knowledge frommanagement: Entrepreneurship (pp. 48-50). Oxford, UK:

multiple disciplines—most prominently, ofBlackwell Publishers.

course, from strategic management and entreBarnard, C. I. (1938). The functions of the executive. Cam

bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

preneurship. The importance of innovation in

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained compet

the global economy, the significance of entreitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

preneurial activity for economic growth, and

Barney, J. B. (2002). Gaining and sustaining competitive ad

the critical value of strategic management forvantage (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice

Hall.

survival and success heighten SE's importance.

Baron, R. A. (2007). Behavioral and cognitive factors in

Research on SE and constructs relevant to it has entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurs as the active element in

burgeoned in the first decade of the 21st cen new venture creation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal,

1(1-2), 167-182.

tury, as evidenced by the increasing number of

Baron, R. A., & Henry, R. A. (2010). How entrepreneurs

journal special issues on the topic and the rapidacquire the capacity to excel: Insights from research on

development of the Strategic Entrepreneurship expert performance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4

Journal. The research in this area over the next(1), 49-65.

Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2000). Beyond social

10 years is likely to grow geometrically. This

capital: The role of social skills in entrepreneurs' success.

work and the model presented herein provide Academy

a of Management Executive, 14(1), 106-116.

base of support and suggest a robust set of Baron,

op R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2003). Beyond social

portunities for enriched inquiry regarding thecapital: The role of entrepreneurs' social competence in

their financial success. Journal of Business Venturing,

effective use of strategic entrepreneurship and18(1), 41-60.

the benefits that can accrue to multiple stakeBaron, R. A., & Tang, J. (2009). Entrepreneurs' social skills

holders as a result. and new venture performance: Mediating mechanisms

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

72 Acodemy of Management Perspectives May

and cultural generality. Journal of A.

Chiles, T., Bluedorn, Management, 35(2),

C., &. Gupta, V. K. (2007). Beyond

282-306. creative destruction and entrepreneurial discovery: A

Batjargal, B., Tsui, A., Hitt, M. A., Arregle, J., Webb, J. W., radical Austrian approach to entrepreneurship. Organi

&. Miller, T. L. (2009). Women and men entrepreneurs' zation Studies, 28(4), 467-493.

social networks and new venture performance across Choi, Y. R., & Shepherd, D. A. (2004). Entrepreneurs'

cultures. Academy of Management Proceedings. decisions to exploit opportunities. Journal of Manage

Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of ment, 30(3), 377-395.

entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subseCoff, R. W. (2002). Human capital, shared expertise, and

quent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, the likelihood of impasse in corporate acquisitions. Jour

89(4), 587-598. nal of Management, 28(1), 107-128.

Baumol, W. J., & Strom, R. ]. (2007). Entrepreneurship andCoff, R. W. (in press). The co-evolution of rent appropria

economic growth. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1-2), tion and capability development. Strategic Management

233-237. Journal.

Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2003). Exploitation, Covin, J. G., &. Slevin, D. P. (2002). The entrepreneurial

exploration and process management: The productivity imperatives of strategic leadership. In M. A. Hitt, R. D.

dilemma revisited. Academy of Management Review, 28 Ireland, S. M. Camp, & D. L. Sexton (Eds.), Strategic

(2), 238-256.

entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset (pp. 309-327).

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L., & Larraza-Kintana, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate reCrook, T. R., Ketchen, D. J., Combs, J. G., & Todd, S. Y.

sponses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled

(2008). Strategic resources and performance: A meta

firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1),

analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 29(11), 1141—

82-113.

1154.

Bruyat, C., & Julien, P. (2001). Defining the field of re

Davidsson, P. (2005). Researching entrepreneurship. New

search in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing,

York: Springer.

16, 165-180.

DeCarolis, D. M., & Deeds, D. L. (1999). The impact of

Burgelman, R. A., & Hitt, M. A. (2007). Entrepreneurial

stocks and flows of organizational knowledge on firm

action, innovation and appropriability. Strategic Entre

performance: An empirical investigation of the biotech

preneurship Journal, 1(3-4), 349-352.

nology industry. Strategic Management Journal, 20(10),

Calas, M. B., Smircich, L., & Bourne, K. A. (2009). Ex 953-968.

tending the boundaries: Reframing entrepreneurship as

Delmas, N. A., & Montes-Sancho, M. J. (in press). Volun

social change through feminist perspectives. Academy of

Management Review, 34, 552-569. tary agreements to improve environmental quality: Sym

Cardon, M., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, J. (2009). bolic and substantive cooperation. Strategic Management

Journal.

The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion.

Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 511-532. Dess, G., & Beard, D. (1984). Dimensions of organizational

Cassar, G., & Friedman, H. (2009). Does self-efficacy affect task environments. Administrative Science Quarterly,

29(1), 52-73.

entrepreneurial investment? Strategic Entrepreneurship

Journal, 3(3), 241-260. Dess, G. G., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2001). Emerging issues in

Castrogiovanni, G. J. (1991). Environmental munificence: strategy process research. In M. A. Hitt, R. E. Freeman,

A theoretical assessment. Academy of Management Re & J. S. Harrison (Eds.), Handbook of strategic management

view, 16(3), 542-565. (pp. 3-34). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Ceccagnoli, M. (2009). Appropriability, preemption, and firmDhanaraj, C., & Parkhe, A. (2006). Orchestrating innova

performance. Strategic Management Journal, 30(1), 81-98. tion networks. Academy of Management Review, 31(3),

659-669.

Chaddad, F., & Reuer, J. (2009). Investment dynamics and

financial constraints in IPO firms. Strategic Entrepreneur Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation

ship Journal, 3(1), 29-45. and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management

Chandler, A. D. (1962). Strategy and structure: Chapters in Science, 35(12), 1504-1511.

the history of the American industrial enterprise. Washing Eckhard, J., & Shane, S. A. (2003). Opportunities and

ton, DC: Beard Books. entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 29(3), 333

Chen, M.-J., Fairchild, G. B., Freeman, R. E., Harris, J. D., 349.

& Venkataraman, S. (2010). What is strategic manage Eikenberry, A. M., & Kluver, J. D. (2004). The marketiza

ment? Darden Business Publishing, UVA-S-0166. tion of the nonprofit sector: Civil society at risk? Public

Chen, M.-J. (1996). Competitor analysis and inter-firm Administration Review, 64(2), 132-140.

rivalry: Toward a theoretical integration. Academy ofGaglio, C. M. (2004). The role of counterfactual thinking in

Management Review, 21(1), 100-134 the opportunity identification process. Entrepreneurship

Chen, X. P., Yao, X., & Kotha, S. (2009). Entrepreneur Theory and Practice, 28(6), 533-552.

passion and preparedness in business plan presentations: Gaglio, C. M., & Katz, J. (2001). The psychological basis of

A persuasion analysis of venture capitalists' funding de opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness.

cisions. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 199— Journal of Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95-111.

214. Gartner, W. B. (2007). Entrepreneurial narrative and a

This content downloaded from

203.175.72.26 on Thu, 16 Mar 2023 19:50:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

2011 Hit), Ireland, Sirmon, and Trahms 73