Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mozart's E-Minor Violin Sonata, K. 304: Music Composition Techniques - Any Old Music

Uploaded by

O ThomasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mozart's E-Minor Violin Sonata, K. 304: Music Composition Techniques - Any Old Music

Uploaded by

O ThomasCopyright:

Available Formats

Free Content Library !

! Any Old Music School !

! Exclusive Content !

! Contact Us

r S z z z r r zt

z z e t z

/ 18th Century, Analysis, Concert Music

Sharing's caring:

F T Li R M E C S

a w n e e mo h

Mozart's Violin Sonata No. 21 in E-Minor, K.304 - Composition Technique

Prefer video, look up. Prefer reading, scroll down.

In early 1778, Mozart was touring from his home in Salzburg to Paris. Stopping in Munich and

Mannheim first, Mozart composed many sonatas on this journey. A collection of these includes

seven Violin Sonatas (No. 17 – 23). The E-Minor Violin Sonata, No. 21/K. 304, is the only minor key

sonata in this collection. I decided to take a look at this sonata, in part for that reason, but also

because I found the clarity of its composition compelling. Using texture to clearly state themes

and then present interesting variants, I think it’s a good demonstration in what I think can be

easily forgotten as a composer or arranger: less can be more. Below I explore the works contextual

origins, before analysing the first movement in more detail, focussing on its composition.

A turbulent period for Mozart. The E-minor Violin Sonata (K. 304)

was composed while he was on a tour that would take him to Paris.

He would also stop off at Munich and Mannheim. Intended as a trip

to grow and spread Wolfgang’s reputation as a composer and

performer, Mozart, along with his family, was hoping he might also

escape Salzburg and Archbishop Colloredo, gaining new

employment in a more favourable court, where he would be

allowed to flourish.

Mannheim, a court held in high regard for its musicians during this

time, is where the E-minor Violin Sonata originates, before being

completed in Paris. There is speculation that the Violin Sonata was

written as a response to Mozart’s mother’s death. However,

according to the description of the linked performance below,

Anna Maria’s death, in Paris, succeeds the first movement and,

possibly, the second movement’s completion, undermining this

hypothesis. (I made an attempt to find the sources that discuss the

paper dating in the above source. However, I was unable to locate

them. If anyone knows where it is, I’d love to know!)

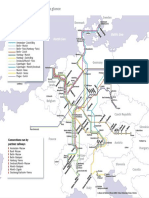

Cambridge

Magdeburg Potsdam

TheHague°Netherlands

London

Antwerp? Esseno Leigzig

Dresden

n Brussels Cologne Germany

Brighton oLille

Belgium

Frankfurt Prague

Rouen 0to53hr Nuremberg Czechia

O 992km cOMannheim

Caen

Paris0*

Strasbourg©

Vie

Freiburgim

°Breisga

ll )Salzburg

ingers TourS -Zürich

O

O

Liechtenstein Graz

O

Switzerland

France oLausanne

alle

Limoges Clermont-Ferrand Lyon

SloveniaZagre

O Trieste

Milan Verona Venice

O

O

Grenoble

Padua

rdeaux

Croatia

Unfortunately, there isn't an 18th-century road or stagecoach option

for Google Maps. However, there is a reason people stayed in places

for a while when visiting: it took a great deal more time and energy

to get between places back then. It's 53-hours of cycling though... if

you wondered.

Surrounding grief-stricken laments, there is a more compelling

argument around the later A-Minor Piano Sonata No. 10, k.310,

which does succeed Anna Maria Mozart’s abrupt death and is the

first minor-key composition to do so. Julia Nagel puts forward a

psychoanalytical case that outlines features in the Piano Sonata

that set it apart from others composed by Mozart, and why the

composition, therefore, could be a response to his mother’s

death.

Toying with this line of enquiry, one can speculate on a different

emotional basis for the composition of this E-Minor Violin Sonata.

While in Mannheim, Mozart became particularly fond of Aloysia

Weber, a soprano who was the older sister of Wolfgang’s later wife,

Constanze. (The portrait of Mozart I use in the image for this post

is actually by Aloysia’s later Husband, Joseph Lange, Mozart’s

eventual brother-in-law.) Delaying his departure, it was only under

duress that Mozart finally succumbed to his Father’s pleas to move

on to Paris in March of 1778. Its possible, although speculative, to

suggest the E-minor Violin sonata is a response to this duress, at

having to leave Aloysia, in Mannheim, and move on to Paris.

There are several novel qualities in the Violin Sonata that facilitate

speculation on its geographical and emotional origins. For instance,

the 1st subject of the Violin Sonata’s 1st movement has a

combination of interesting characteristics. These are its upward

skipping contour, reminiscent of a Mannheim rocket, combined

with the bel canto style lyricism typical of Mozart’s writing.

Emphasised further by the minor tonality, these qualities generate

a potent feeling of melancholy, reflective of his reluctance and

despair at leaving love behind in Mannheim.

MozartViolinSonatainE-Minor

Bar1-12,FirstSubject

Mannheimrocket,

Legatoarticulation, epf' ertepflp yolor

Pianodynamic

Shortar ticulation,

Fortedynamic

The opening 12 bars of Mozart's E-Minor Violin Sonata (K. 304),

annotating the contour and the juxtaposition of legtato-piano and

staccato-forte.

Sogno di Volare – Music Composition Techniques

In this article/video, I take a look at the composition technique used

in Christopher Tin's composition for Civilisation 6, Sogno di Volare.

Unearthing more than I expected to, there is a range of techniques

to take from this piece. For example, the interconnection of musical

structures and the use of established form.

Read More »

The second quality of this first movement is its juxtapositions of

dynamics and articulation, creating abrupt shifts between brooding

melancholy and irritable frustration. There are regular switches

between forte and piano, frequently accompanied by alternations

from legato to staccato playing. Considering the second movement

as well, which uses dolce and sotto voce markings, along with

crescendos and diminuendos, to add further dynamic range, these

are significant details. Across Europe, the Mannheim court of

musicians had a reputation for being particularly capable of

realising such dynamic nuances and sudden changes in their

performances.

The minuet and trio, second movement, boasts additional

emotional qualities of lovesickness. In listening to and analysing the

piece, the outer minuet sections remind me of emfindsamer stil or

the sensitive style of music composition. Notably explored by JS

Bach’s sons CPE and WF Bach. Using suspensions, appoggiaturas

and melodic and accompaniment textures, there is an undeniable

sensitivity to this movement that could be attributed to Mozart’s

sadness at having to leave Aloysia Weber behind in Mannheim. Or,

if the composition of this movement does succeed the death of

Anna Maria Mozart, then it could also be a response to that.

Referring tentatively to the source I’ve not been able to… source, in

original form at least, the second movement was written later.

Speculative, I find these musical and contextual relationships

compelling to explore. One can find a clear influence of distinct

Mannheim features and sensitivity in Mozart’s Violin Sonata. Often

described as a sponge, the deliberate referencing and use of such

musical language, by Mozart, are very plausible. The rare use of a

minor mode also facilitates speculation on its emotional origins.

However, albeit less exciting and mystical, the reasoning could be

much more straightforward. Mozart had composed five Violin

sonatas on the trip already. Each of these was in a major tonality.

Perhaps, in a bid to demonstrate versatility in his craft–to potential

employers–Mozart composed a minor tonality composition that

showed off his ability to express sensitive emotions? Come to think

of it. I think I prefer that last one. I wish I’d thought of it sooner!

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical

knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link.

Thank you.)

Mozart - Violin Sonata No. 21, E Minor (K.

304), 1778. [Score Video]

Mozart - Violin Sonata No. 21, E Minor, K. 304 [Szer…

Mozart’s Violin Sonata in E-Minor, K. 304 has two movements: a

sonata-allegro and a minuet and trio. Two movement sonatas were

not unusual at this time as, while sonata form was perpetually

developing, these were its formative years. Just as the symphony

was transitioning from three to four movements, the sonata was

going from two to three. This sonata is one of the last that Mozart

composed in two movements. He experiments with the 3-

movement schema when composing his piano sonatas during this

period. (K. 309, Piano Sonata No. 7, for instance, has three

movements. Its composition is believed to be a little before the E-

Minor Violin Sonata.)

In this analysis, I want to focus on the first movement. I believe

there are valuable concepts that can still be learned from this

movement that will enhance our thinking as composers and arrangers:

particularly the presentation and control of musical ideas. Therefore, for

this analysis I want to pay particular attention to the overall structure of

the first movement: how Mozart orders his ideas within the larger

sonata schema; and how he develops his themes, looking particularly at

his use of fragmentation in polyphonic textures.

The structure of K304 is a broader sonata procedure. A form, as I

have said, in developmental flux, it is possible to distinguish

functional periods within the Violin Sonata that can be defined and

labelled as sonata form sections. For instance, the work has a clear

exposition, where Mozart communicates the thematic material to

his audience. The development section is where the bulk of

thematic variation is. Although in reality, the development of ideas

is not confined only to this section and Mozart does compelling

things with his melodies while in transition, between statements

and restatements of the main melodies. The development section

is, typically, in a different key to the home key of the sonata, while

the recapitulation restates themes in the home key. Mozart follows this

strategy by modulating to B-minor for the beginning of the

development section, returning to E-minor in the recapitulation.

Bar Section Sub-section Tonality Texture ThematicDetails(T=Theme;S=Subject)

1 M T1&T2

Subject1 Em

13 M&A T1

19 Am<->Em TransitionalMaterial1

Transition

27 C,G,C,D,G,Gm H TransitionalMaterial2:(S2)T1(Fragmented;)

43 Exposition Subject2 M&A T1

57 G Homophonic (S2)T1(Fragmented;altered)

75 Transition M->H (S1)T2(restat.;majormodetransposition)

65 Em->G H->M&A (S2)T1(Fragmented;liquidated)

75 Codetta G->Em P(canon) (S1)T1(majormodetransposition)

83

Development

S1&S2 Bm M->P Bothsubjectgroupsincounterpoint

98 Transition G,Em,Bm Homophonic S2(T1)fragment

108 Subject1 Em M&A T1

118 Am<->Em TransitionalMaterial1

Transition

126 F,C,Am,Bm,Em H->M&A TransitionalMaterial2:(S2)T1(Fragmented;)

143 Subject2 M&A T1(minormodetransposition)

Recapitulation Em

151 Homophonic (S2)T1(Fragmented;altered)

157 Transition Em/B M->H (S1)T2

171 Em<->Am H->M&A (S2)T1(Fragmented;liquidated)

180 Codetta Em P(canon) (S1)T1

190 Coda Subject1 Em;Am<->Em;Em M&A T1&TransitionalMaterial1restatement

Structural breakdown of the first movement to Mozart's Violin

Sonata in E-Minor (k.304) Highlighting Sonata form the table also

highlights other details such as texture and tonality.

Aesthetic for this period, Mozart uses closely related keys. On a larger

scale, Mozart follows a typical modulatory schema. The work starts, in

the exposition, and ends, in the recapitulation, in the home key of E-

minor. For the second subject and development section, Mozart

modulates to two different keys. In the second subject, the composition

moves to the relative Major, G, and in the development to the minor

dominant, B. A typical strategy of this time, many works, including

sonata form movements, start in the home key, modulating elsewhere

through middle sections of the composition. Usually to a relative or

dominant key, which is what Mozart does here.

Including smaller scale modulations, if we look at the circle of 5ths,

we can more easily see the closeness of all the keys Mozart uses in

his work. To distinguish the larger scale modulations, I use red

circles. For the smaller, passing modulations I use blue circles. In

combination with the above table, the 2nd subject and

development section are where the work stays within these

different keys for the longest time. It is in the transition section

where we have passages that pass through many keys quickly, but

in so doing, we travel the furthest from the home key of E-minor.

The most distant modulation here is the parallel major-minor

switch in the expositions transitionary section, where Mozart

modulates directly from G-Major into G-Minor and then back again.

However, despite being visually more distant, the fact the two are

parallel tonalities means they share the same root and core

harmonic tones. For example, Mozart uses a D-pedal through this

passage to both underpin the G-minor but also build excitement, in

the form of a dominant preparation, for the second subject, which is

in G-Major. D is the shared dominant of both G minor and major,

being the 5th degree, or V, of G (major and minor).

Major

iC

B la

4 0

b Minor

,2

"g; 15

在E36C £#3#A基

5

8 bb

c#

成

卫

46

eb/d# 56/7# 76/5#

66/6#

D B

Gb/F#

C= 蜌華

Red highlights core, larger scale modulations where the

tonicisation of each key is static for longer. Blue circles highlight

tonalities that are passed through, only briefly tonicised. As can be

seen, the keys are all closely related, often adjacent, on the circle of

5ths.

Get video content too, subscribe on

YouTube.

! ! !

Along with modulations, Mozart also uses texture to create interest

and clarity in his thematic material. (Similar to Guiraud’s use of

texture for Bizet’s Farandole.) Melody and accompaniment is the

prominent texture of the composition. However, Mozart also makes

use of Polyphony. Homophony is used sparingly, used most

frequently within inner voices as part of a larger melody and

accompaniment texture.

To me, the opening monophonic texture of Violin and Piano in

octave unisons is a startling opening. Especially when mixed with

the piano dynamic level and brooding minor tonality. This response

could, in large part, be due to Mozart’s often upbeat, major tonality

compositions. It is a stark contrast within the larger context of his

catalogue of works.

Mozart uses monophony, or more frequently, melody and

accompaniment in sections where initial thematic statements or

restatements happen. In these passages, the accompaniment part

switches between two forms. Firstly, broken chord, Alberti bass

figurations and, secondly, chordal structures, reminiscent of

homophony. (While homophonic between the chordal voices, often

in a particular hand of the piano, in the larger textural context they

play the role of accompaniment.)

Two forms of Melody & Accompaniment from K. 304: (1) block

chords & melody; (2) broken chord figuration & melody.

Mozart also uses two forms of polyphony in this composition: canon

and imitative counterpoint. In the passages that I label as codettas,

Mozart presents the first theme, of the first subject, in a 2-part

canon. This textural distinction, along with their positioning: just

before the repeat markings, is what led me to distinguish them as

codettas. In the transition sections and development section Mozart

uses imitative counterpoint. Clearest in the development section, this is

where Mozart counterpoints themes of different subject groups. He uses

polyphony as one of the large scale ways in which to develop his

material.

The opening theme, presented as a canon at the end of the

exposition. (The left hand of the piano is bass clef)

I do not think it is an accident that there is a correlation between

exposition, restatement and melody and accompaniment textures,

while polyphony is reserved for transitional and development

sections. Melody and accompaniment textures inherently elevate

the prominence of melody. In stating his themes, Mozart wants us

to identify them with ease. The satisfaction of a sonata form, from a

listener’s perspective, is being able to hear these themes and then

spot them in more complex variations and settings. In other words,

as the composer, Mozart wants us to identify his themes, so he can

show us how clever he is in developing them.

Enjoying

the

article?

Get notified of our latest releases, as

soon as we publish.

Direct to your inbox.

Enter email here

Submit

Unsubscribe links are included at the

beginning and end of each email.

How to repeat melodies without them getting

boring… [Video]

A video composition lesson looking at textural variation as a device

for melodic development.

Read More »

Thematically I have already alluded to two ways in which Mozart

develops his material. One of these is through modulation, taking

his themes through different keys. Another is through setting them

in different textures. These changes are broader, with Mozart

imposing the challenge of fitting each idea into a new tonal or

textural context. However, Mozart also uses a smaller-scale

developmental technique known as fragmentation. I want to

highlight his use of this technique, by extracting the original

melodies and some of these developments, as they are still useful

techniques that we can use today in our music-making.

The first theme that Mozart presents is a lyrical, bel canto style

melody. With the anacrusis it spans 8-bars. The second 4-bar

phrase is important in the development section, as we will see,

while its opening arpeggio figure that I liken to a Mannheim rocket

is distinctive. Its inner contours are largely upward, but on a larger

scale it is always falling back to where it started.

The first theme of the second subject has two distinguishing

characteristics. The first is its emphasis on dotted rhythmic patterns,

followed secondly by its V-shaped contour. The dotted rhythms are

particularly important to developments of this theme within the

transitional sections of the work (yellow annotation, in below

image). While the descending, straight quaver passage (blue) and

octave leap (yellow) become important in the development section

of the composition.

Distinct from one another, below, I have extracted each of these

themes, annotating their characteristics.

Theme 1 of Subject 1 and Theme 1 of Subject 2 from K.304.

The second subject theme has the most smaller-scale

developments. In the transitional sections of the exposition and

recapitulation, we can extract several iterations of the dotted

rhythm, fragmented from the theme. While it is possible Mozart

composed the work linearly, there is further reinforcement of the

lessons learned from arranging London Bridge, and the non-

linearity of ideas in the composing process. For instance, it is also

just as possible that Mozart had composed his two subjects and

then figured out the transition afterwards.

Example of Subject 2 preempting itself in the preceding transition

section. Annotations highlight the fragmentation of the dotted

rhythm from subject 2, theme 1 (see previous image).

In the development section, Mozart uses larger fragments of the

themes, placing them in counterpoint. The use of the first theme is

clear, appearing first in full form. The only apparent change, initially,

is its transposition into the key of B-minor. Mozart then fragments

this theme, focussing on the second 4-bar phrase, counterpointing

it with both itself and a fragment of the second subject.

The second subject’s use is less obvious. Mozart fragments the

second portion of this theme where the melody descends in

straight, rather than dotted quavers. He then alters the rhythm,

while maintaining key intervallic and contour features. Placing the

extracts together, with annotations demonstrates the second

subjects use in this section of the composition.

Placing the themes in a different texture is a larger-scale way of

developing the material. Mozart can extract larger fragments,

juxtaposing them to create a compelling moment of polyphony. All

the while he is not reinventing the wheel, using material he has

already exposed.

Annotation of the development section. The colours correspond to

those used in the image that extracts the two themes: subject 1,

theme 1 and subject 2, theme 1.

! " ! # $

I always think of sonata, or any established form for that matter, as

being like a species of animal. Similar forms have underlying

skeletons that might be indiscernible beyond species alone.

However, when you give them their form, adding the flesh, skin and

hair (if its fortunate enough to have any…) the variety becomes

much more vast. We can identify individual people or animals

through their appearance, just as we can identify different pieces.

However, if you look under the surface the structures can be very

similar.

Thinking about this similarity of the underlying structure but the

difference of outer form. The first, broader, takeaway is one of

exploration. Why not explore established forms in your writing?

Mozart, in my opinion, was an exceptional exploiter of form, creating

novelty within its confines. I think this is also why his music has

entered and remains firmly within the western musical classical

canon. In using forms we understand his music immediately

becomes more accessible as we know how to listen to it and, as a

result, appreciate it. Now, appreciation might not be an aesthetic

goal and I’m not saying it should be, but its a concept that is helpful

to be aware of.

On a smaller level, Mozart’s E-Minor Sonata, No. 21 (K.304),

demonstrates techniques we can try and apply in our work. Even if

we dress it up differently! For example, while we might not want to

use many I-V relationships, we can certainly use texture and

melodic fragmentation to develop our musical ideas, refreshing

them for our listeners. In your next composition or arrangement,

why not try counterpointing fragments of your melody in a small

passage of your work? Why not use a texture you use less

frequently at an important point in the work, perhaps the

beginning, taking your listeners by surprise?

Auke J2 (2012) Mozart Piano Sonata No. 8 in A-Minor KV. 310,

Grigory Sokolov [Video].

Bartje Bartmans (2016) Mozart – Violin Sonata No. 21, E Minor, K. 304

[Szeryng/Habler] [Video].

Gay, P. (1999) Mozart. London: Phoenix.

Mozart, W. A. (1778) Violin Sonata in E minor, K. 304/300c [Musical

Score]. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Hartel, 1879.

Nagel, J. J. (2007) Melodies of the Mind: Mozart in 1778. American

indigo 64(1), pp. 23-36.

Reitenga, B. (2011) A comparative analysis of the role of the violin in

the sonatas of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with special attention

to the early sonata k. 304 and the late sonata K. 526. MA Thesis.

Ball State University, Indiana.

Wikipedia (n.d.) Kochel catalogue [Website].

Wikipedia (n.d.) Violin Sonata No. 21 (Mozart) [Website].

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams The Lark Ascending (Music

(Impromptu Melodic Analysis) Composition Analysis) – Ralph

" 21st Century, Analysis, Film Music Vaughan Williams (Article 1 – Lessons

An impromptu analysis of the comedic melodies in Harmony)

" 20th Century, Analysis, Concert Music

John Williams created to underscore the devious,

Gilderoy Lockhart, in Harry Potter and the An analysis that looks at modality (modulation &

Chamber of Secrets. interchange), pedal points and chord voicing in

RVW’s The Lark Ascending.

How to repeat melodies without 5 ways of Understanding woodwinds

them getting boring… [Video] " Concepts of Music, Orchestration

" Composition, Concert Music

This week I was fortunate enough to stumble on a

A video composition lesson looking at textural YouTube video by composer Zach Heyde. In this

variation as a device for melodic development. video he analyses the …

Arabesque No. 1 – Claude Debussy Spiegel im Spiegel – Arvo Pärt

(Music Composition Analysis) " 20th Century, Analysis, Composition

" 19th Century, Analysis, Composition

Unpicking the serenity of Pärt’s Spiegel I’m

An analysis of Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1, looking Spiegel: Tintinnabuli technique is recapped along

at structure, melody and harmonic language. with the identification of other creative

constraints.

Enjoying the

article?

Get notified of our latest releases, as soon as we publish.

Direct to your inbox.

Enter email here

Submit

Unsubscribe links are included at the beginning and end of each email.

Sharing's caring:

F T Li R M E C S

a w n e e mo h

← Previous Post Next Post →

Hello. If you have any

Copyright © 2023 George Marshall questions, fire away!

Free Content Library Any Old Music School Exclusive Content Contact Us

Chat

You might also like

- Avenue of SpiesDocument18 pagesAvenue of SpiesCrown Publishing Group100% (2)

- Imagining the Nation in Nature: Landscape Preservation and German Identity, 1885–1945From EverandImagining the Nation in Nature: Landscape Preservation and German Identity, 1885–1945No ratings yet

- Piano Junior Lession Book 1Document49 pagesPiano Junior Lession Book 1Thu Trang Vũ100% (1)

- Alpine Ski Touring SampleDocument26 pagesAlpine Ski Touring SampleyoboloNo ratings yet

- German Illustration BookDocument62 pagesGerman Illustration BookZuzana KovarovaNo ratings yet

- UK, Ireland & France - WatermarkDocument33 pagesUK, Ireland & France - WatermarkPLANESTURISTICOSCOM ViajesNo ratings yet

- Hoffmeister Clarinet ConcertoDocument10 pagesHoffmeister Clarinet Concertorubén DiazNo ratings yet

- A Study GuideDocument22 pagesA Study GuideJosé Givaldo O. de LimaNo ratings yet

- Opera Now - September-October 2020Document86 pagesOpera Now - September-October 2020Chris W. BalmerNo ratings yet

- Germany and The Second World War - Volume I - The Build-Up of German Aggression (PDFDrive)Document809 pagesGermany and The Second World War - Volume I - The Build-Up of German Aggression (PDFDrive)Parabellum100% (4)

- Gildea Fighters in The Shadows - FinalDocument607 pagesGildea Fighters in The Shadows - FinalJorge CanoNo ratings yet

- Frankfurt's Modern Architecture and Cultural InstitutionsDocument1 pageFrankfurt's Modern Architecture and Cultural InstitutionsRama KeshkehNo ratings yet

- Explore night train routes across Europe at a glanceDocument1 pageExplore night train routes across Europe at a glanceLoyd RidgewellNo ratings yet

- Italy PhysiographyDocument1 pageItaly PhysiographydeusNo ratings yet

- Be Inspired by Nature: Capitais Europeias - Horas de VooDocument2 pagesBe Inspired by Nature: Capitais Europeias - Horas de VooTeresaMendesNo ratings yet

- Operations Areas: of AttachingDocument37 pagesOperations Areas: of Attachingchim yan qiNo ratings yet

- Clones 1m1 Opening Sheet MusicDocument4 pagesClones 1m1 Opening Sheet Musickeman91No ratings yet

- Formulir Pas-Foto-Tanda-Tangan-Mahasiswa UT AM01 RK04c RII.1Document4 pagesFormulir Pas-Foto-Tanda-Tangan-Mahasiswa UT AM01 RK04c RII.1Hana TatataNo ratings yet

- Kami Export - Terry Brown - After WW 1 MapDocument2 pagesKami Export - Terry Brown - After WW 1 Mapsolozp224No ratings yet

- Rise of The Guardians - DesplatsDocument458 pagesRise of The Guardians - DesplatsGabriel100% (1)

- L Italia RegionaleDocument4 pagesL Italia RegionaleElena RomeoNo ratings yet

- Postcard ArtworkDocument2 pagesPostcard Artworkapi-3855431No ratings yet

- Sylvia Honnor, Heather Mascie-Taylor and Michael SpencerDocument14 pagesSylvia Honnor, Heather Mascie-Taylor and Michael SpencerdlaminibongieNo ratings yet

- WhattamSIR CMP11Document15 pagesWhattamSIR CMP11Gurbuz GorguluNo ratings yet

- Apprenons Le Francais - Lecon 0Document4 pagesApprenons Le Francais - Lecon 0Elfreda D'souzaNo ratings yet

- PDF. Rhine Cycle Route!Document105 pagesPDF. Rhine Cycle Route!Álvaro PardoNo ratings yet

- Pages From Pianofforte1Document2 pagesPages From Pianofforte1luussiinNo ratings yet

- Alexandre Desplat - The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (Full Score)Document336 pagesAlexandre Desplat - The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (Full Score)Andrea Fagioni100% (2)

- Prague: Staronová Synagoga (Old-Ne..Document21 pagesPrague: Staronová Synagoga (Old-Ne..Alina Maria BeneaNo ratings yet

- Rim Seal Area For Floating Roof Tanks Rafp: Detection & Extinguishing SystemDocument3 pagesRim Seal Area For Floating Roof Tanks Rafp: Detection & Extinguishing SystemshijuNo ratings yet

- The Art Journal LondonDocument463 pagesThe Art Journal LondonJohn TrampNo ratings yet

- Map Fes Morocco Guide Com PDFDocument1 pageMap Fes Morocco Guide Com PDFyartaawihassanNo ratings yet

- Global Retail Trends and Innovation 2018Document114 pagesGlobal Retail Trends and Innovation 2018Hasan GilaniNo ratings yet

- SK Nacht Auslandsbahnen E-FinalDocument1 pageSK Nacht Auslandsbahnen E-FinalBreno CostaNo ratings yet

- T G 401 Illustrated Map of Germany Display Poster - Ver - 1Document1 pageT G 401 Illustrated Map of Germany Display Poster - Ver - 1SKL xxNo ratings yet

- La Maison Du Gruyere Anglais 2021Document2 pagesLa Maison Du Gruyere Anglais 2021Maximiliano TaubeNo ratings yet

- Achievement Chart MacasDocument4 pagesAchievement Chart MacasJenn MacasNo ratings yet

- Progress Chart MacasDocument4 pagesProgress Chart MacasJenn MacasNo ratings yet

- Violine, Klavier, Johannes Brahms - Ungarischer Tanz Nr.6 (Bearbeitung Joseph Joachim)Document6 pagesVioline, Klavier, Johannes Brahms - Ungarischer Tanz Nr.6 (Bearbeitung Joseph Joachim)MUVESZNo ratings yet

- (Synthesis Lectures On Quantum Computing) Marco Lanzagorta-Quantum Radar - MC (2012)Document141 pages(Synthesis Lectures On Quantum Computing) Marco Lanzagorta-Quantum Radar - MC (2012)Wilmer Moncada100% (1)

- The CURSE of FRANKENSTEIN - 9M2 - Guillotine (Complete Version)Document7 pagesThe CURSE of FRANKENSTEIN - 9M2 - Guillotine (Complete Version)RozsafanNo ratings yet

- Poster 1 by #Abhc00086Document1 pagePoster 1 by #Abhc00086NammuBondNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 89.164.29.222 On Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTCDocument56 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 89.164.29.222 On Sat, 23 Jan 2021 16:14:40 UTCLjuban SmiljanićNo ratings yet

- Paisagem Brasileira UNIRIODocument23 pagesPaisagem Brasileira UNIRIORicardo MichelinoNo ratings yet

- Welding and CuttingDocument64 pagesWelding and CuttingScott TrainorNo ratings yet

- NullDocument1 pageNullM-NCPPCNo ratings yet

- Harti BizantinologieDocument12 pagesHarti BizantinologiemcaNo ratings yet

- Nimrod - ScoreDocument6 pagesNimrod - ScoreMonica van der VeldeNo ratings yet

- Clones 2m1aDocument8 pagesClones 2m1akeman91No ratings yet

- Czech Republic MapDocument1 pageCzech Republic MapMihai IonescuNo ratings yet

- 3m26 FlashbackDocument24 pages3m26 FlashbackDaveNo ratings yet

- 6/19 Partitur: LigetiDocument16 pages6/19 Partitur: LigetiLaTonya Hutchison 101No ratings yet

- GP24 Visitor Map FINALDocument1 pageGP24 Visitor Map FINALHayden CNo ratings yet

- Harry Tries To LeaveDocument7 pagesHarry Tries To LeaveSoraya Unión ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- Brussels: in Collaboration With Visit BrusselsDocument18 pagesBrussels: in Collaboration With Visit BrusselsDan ȘtețNo ratings yet

- Sparse Representations For Radar With MATLAB Examples (Peter Knee) (Z-Library)Document87 pagesSparse Representations For Radar With MATLAB Examples (Peter Knee) (Z-Library)Venkateswaran NNo ratings yet

- Ryanair Magazine August - September 2010Document168 pagesRyanair Magazine August - September 2010jman5000No ratings yet

- James Horner Score The Darkside of The Moon - Apollo 13Document18 pagesJames Horner Score The Darkside of The Moon - Apollo 13Clément BlondiauNo ratings yet

- Clones 5m1Document6 pagesClones 5m1keman91No ratings yet

- Tightrope-DrumsetDocument2 pagesTightrope-DrumsetO ThomasNo ratings yet

- UK National Anthem-Pop Band-TopDots OrchestrationsDocument30 pagesUK National Anthem-Pop Band-TopDots OrchestrationsO ThomasNo ratings yet

- B12 PresentationDocument5 pagesB12 PresentationO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Virtual_Insanity-PianoDocument4 pagesVirtual_Insanity-PianoO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Purple_Rain-Alto_Saxophone_2Document1 pagePurple_Rain-Alto_Saxophone_2O ThomasNo ratings yet

- Pnas 1414495112Document6 pagesPnas 1414495112O ThomasNo ratings yet

- Machaut B12 (Earp Details)Document1 pageMachaut B12 (Earp Details)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- Original Song-PianoDocument7 pagesOriginal Song-PianoO ThomasNo ratings yet

- OLD DOGS, NEW TRICKS-BASS - (5-String)Document3 pagesOLD DOGS, NEW TRICKS-BASS - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- 4c. TRANSITION MUSIC 1-PIANODocument1 page4c. TRANSITION MUSIC 1-PIANOO ThomasNo ratings yet

- 5a. TRANSITION MUSIC 2-BASS - (5-String)Document1 page5a. TRANSITION MUSIC 2-BASS - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- 00 ZContentsDocument1 page00 ZContentsO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Critical Listening of So Nice Summer SambaDocument1 pageCritical Listening of So Nice Summer SambaO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Zatorre 2005, Music, The Food of NeuroscienceDocument4 pagesZatorre 2005, Music, The Food of NeuroscienceO ThomasNo ratings yet

- 2a. Don't Rain On My Parade-Bass - (5-String)Document1 page2a. Don't Rain On My Parade-Bass - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- Ballad-PianoDocument5 pagesBallad-PianoO ThomasNo ratings yet

- 4b. The Unholy Trinity-Bass - (5-String)Document1 page4b. The Unholy Trinity-Bass - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- 4a. Not Rachel's Song-Bass - (5-String)Document1 page4a. Not Rachel's Song-Bass - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- 000 VocalsDocument1 page000 VocalsO ThomasNo ratings yet

- 4d. Send Them To Hell-Bass - (5-String)Document1 page4d. Send Them To Hell-Bass - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- 1a. Don't Stop Believin'-Bass - (5-String)Document1 page1a. Don't Stop Believin'-Bass - (5-String)O ThomasNo ratings yet

- 7 8immigrationDocument1 page7 8immigrationO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Emilia Denounces Iago - Act 5 Scene 2: Killer Question: Was Shakespeare A Feminist Writer?Document1 pageEmilia Denounces Iago - Act 5 Scene 2: Killer Question: Was Shakespeare A Feminist Writer?O ThomasNo ratings yet

- Specimen Music PaperDocument39 pagesSpecimen Music PaperO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Chords Unit 2 - InversionsDocument1 pageChords Unit 2 - InversionsO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Bach's Violin Concerto in A minor 2nd movement andanteDocument4 pagesBach's Violin Concerto in A minor 2nd movement andanteO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Tiny Dancer: Elton JohnDocument2 pagesTiny Dancer: Elton JohnO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Women in Love ParagraphDocument1 pageWomen in Love ParagraphO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Comparing and Linking Texts Across Genres and TimeDocument2 pagesComparing and Linking Texts Across Genres and TimeO ThomasNo ratings yet

- Upgrade To Immersive Home Theater: Denon Avr-S750HDocument2 pagesUpgrade To Immersive Home Theater: Denon Avr-S750HAadil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Czarth DDocument9 pagesCzarth DLoïc Alexandre ChahineNo ratings yet

- El Cuarto de Tula - GUITAR PDFDocument1 pageEl Cuarto de Tula - GUITAR PDFPiotr KraśnerNo ratings yet

- The Long Tail and Web 2.0Document29 pagesThe Long Tail and Web 2.0Robert CranhamNo ratings yet

- CCL - Sacrifice - Han SeongwooDocument3 pagesCCL - Sacrifice - Han SeongwooReanaNo ratings yet

- Yesterday by Haruki MurakamiDocument16 pagesYesterday by Haruki MurakamiAhafiz100% (1)

- PCM and Pulse ModulationDocument27 pagesPCM and Pulse ModulationPruthvi TrinathNo ratings yet

- Listening 1Document4 pagesListening 1anca_balinisteanuNo ratings yet

- PrintDir 1Document426 pagesPrintDir 1Gabriel PerezNo ratings yet

- English 3 - Modals Workshop Fill in The Blanks Using MUST, MUSTN'T, DON'T HAVE TO, SHOULD, SHOULDN'T, MIGHT, CAN, CAN'TDocument2 pagesEnglish 3 - Modals Workshop Fill in The Blanks Using MUST, MUSTN'T, DON'T HAVE TO, SHOULD, SHOULDN'T, MIGHT, CAN, CAN'TJeisson YepesNo ratings yet

- Script For JS PROMENADE Final 2016Document4 pagesScript For JS PROMENADE Final 2016Villie AlasNo ratings yet

- Gopalakrishna Bharathi Songs YoutubeDocument2 pagesGopalakrishna Bharathi Songs YoutubeJoeyNo ratings yet

- 6C SFP 0320 PDFDocument9 pages6C SFP 0320 PDFizziah skandarNo ratings yet

- Psalm 103 (102) I SorokaDocument3 pagesPsalm 103 (102) I SorokaDANANo ratings yet

- What Are Things Louis Tomlinson Finds Attractive in Girls - Google SearchDocument1 pageWhat Are Things Louis Tomlinson Finds Attractive in Girls - Google SearchSamantha BerrioNo ratings yet

- BeethovenDocument6 pagesBeethovenWaye EdnilaoNo ratings yet

- Relevant Episodes of Detective ConanDocument15 pagesRelevant Episodes of Detective ConanHannah LabordoNo ratings yet

- LeslDocument7 pagesLeslMiguel Angel MartinNo ratings yet

- Nyfa Brochure PDFDocument434 pagesNyfa Brochure PDFLucas FioranelliNo ratings yet

- History of the Russian music duo t.A.T.uDocument12 pagesHistory of the Russian music duo t.A.T.uBiswajit Paul100% (1)

- Pans Ops: A320 FamilyDocument26 pagesPans Ops: A320 FamilyAndreas Bauer100% (1)

- Exam Drill Math 2Document3 pagesExam Drill Math 2Dennis Nabor Muñoz, RN,RM0% (1)

- Chuyên Đề Bài Tập Phát Hiện Lỗi Sai Tiếng Anh-Nguyễn Tiến Dũng PDFDocument20 pagesChuyên Đề Bài Tập Phát Hiện Lỗi Sai Tiếng Anh-Nguyễn Tiến Dũng PDFcauchutnt100% (1)

- LUNA enDocument2 pagesLUNA enAlex Burcea0% (1)

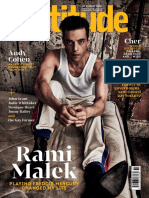

- 2018-10-01 AttitudeDocument180 pages2018-10-01 Attitudeglamourbsas50% (2)

- Pallavi CallingDocument78 pagesPallavi CallingcasaglobalinfraNo ratings yet

- The Piano Digital Accordion. The Modern For Traditional Instruments. Perfomance Contexts PDFDocument153 pagesThe Piano Digital Accordion. The Modern For Traditional Instruments. Perfomance Contexts PDFGilmar gonçalves100% (2)

- Service Manual Mbo Alpha 26xx - 27xx - 28xxDocument42 pagesService Manual Mbo Alpha 26xx - 27xx - 28xxCordobel ValentinNo ratings yet

- Easy To Use, Rugged and Compact With Icom's "V Speed" Audio!Document2 pagesEasy To Use, Rugged and Compact With Icom's "V Speed" Audio!Ojeda O GerardNo ratings yet

- ONA Fact-Finding Trip To JapanDocument23 pagesONA Fact-Finding Trip To JapanDouglas HopkinsNo ratings yet