Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peterson 1981

Uploaded by

BździelKrzysztopórOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Peterson 1981

Uploaded by

BździelKrzysztopórCopyright:

Available Formats

ELEMENTS OF SIMPLEX

STRUCTURE

RICHARD A. PETERSON

HOWARD G. WHITE

ONE OF THE CARDINAL CONCERNS of social science is

how individual competitiveness is socially patterned. The

rules of formal organizations are important in curbing com-

petition, but competition does not often become a free-for-

all, even in those situations where the stakes are high and

there is no formal organization that enforces order. Informal

organizations must have means of coping with competition,

but what are they?

This question focused our attention several years ago on

recording-session musicians in the commercial music in-

dustry. These skilled musicians work on a free-lance basis

so that each theoretically competes with all others for the

brief, demanding, well-paying, and prestigious work of

playing the &dquo;background music&dquo; which augments the ef-

forts of star performers. Our earlier study (Peterson and

White, 1979) found that overt competition was slight and

channeled along specific lines even m the absence of formal

organizational mechanisms shaping these arrangements

AUTHORS’NOTE We gratefully acknowledge the generous help of the following

people who have provided key Insights for this article !var Berg Joel Best Richard

Brown, Derral Cheatwood, Paul DWMaggso, Kenneth Dorow Robert Falkner

URBAN LIFE Vol 10 No 1 April 198. 324

~CD 1981 Sage Publications Inc

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

4

While not formally constituted, the arrangements inhibiting

competition insured that only a few of the musicians

received virtually all of the recording-session work. Those at

the center of the system explained that the best get the

work, but independent observations showed that the active

musicians, while competent, were not always those with

the greatest musical proficiency. This observation triggered

~ the quest for the social mechanisms which were patterning

t the competition. Simplex is the name we have given to the

set of mechanisms used by the few musicians to gain an

oligopolistic position in what was designed as an open

market for recording jobs.

In all its ethnographic detail, the musicians’ simplex is

surely unique, but the same mechanisms may be found

elsewhere. Here we seek out the sorts of situations in

which the simplex can flourish.

PEERS IN COMPETITION

Two factors seem to importantly condition the simplex and

set this form off from most other sorts of informal groups.

First, the simplex is composed of peers, that is, individuals

who occupy the same position in the relevant social situa-

tion. Second, the simplex develops where each individual

would otherwise be in competition with all others. Thus, for

example, the members of a given simplex in our earlier

musician study played the same instrument.

Gerald Hage, Paul Hirsch, Michael Hughes, Charles Kadushm, Peter Manning,

Gerald Marwell, Alan Masur, Ricky McCarty, Walter Powell, John Ryan, Clinton

Sanders, Robert Stern, Ann Swidler, Michael Useem, Harrison White, Margaret

Wyszomirski, Mayer Zald, and Vera Zolberg. We are also grateful to the National

Endowment for the Arts for providing the first author with research leave while the

article was being formulated.

EDITOR’S NOTE. In their previous article (Urban Life, January 1979), Peterson and

White detailed the characteristics of the simplex, a form of association found

among recording studio musicians in the phonograph recording industry. Here

they seek the general characteristics of the simplex and suggest the situations

where it may be found among individuals, organizations, industries, and nations in

competition.

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

5

Peer-based groups are the exception rather than the rule

among human collectivities. Most sorts of groups are com-

posed of persons who are drawn to each other precisely

because of their differing talents, contacts, and knowledge

(Granovetter,1974; Kadushm, ~1 975, Fischer, 1977; Denich,

1978). And groups may accent differences among individuals

m order to increase interdependence. As Durkheim noted,

differences in the division of labor by sex are greatly

exaggerated in most societies so that men and women will

regularly need each other for a wide range of services.

In this article we trace the development of simplical

structures in three different sorts of situations;

first, where

Individuals are in competition, second, where organizations

rather than individuals are m competition, and third, where

Individuals within organizations combine in order to accom-

modate not to market-induced competition, but to the com-

petition among peers which has been induced by formal

rules.

SCHOOLS

Not all groups composed of peers form simplexes. Other

groups composed primarily of peers include what have been

termed &dquo;schools,&dquo; &dquo;circles,&dquo; and &dquo;brokerage&dquo; systems. These

will be examined briefly in order to better detail the condi-

tions conducive to simplex-formation.

Sometimes competing peers collectively gain control over

the evaluation of their own performance by successfully

asserting that they alone can interpret and propagate a

single authoritative body of knowledge based on science,

religion, or tradition. Examples Include contemporary phy-

sics, medieval craft guilds, the French Royal Academy of

Arts, the free professions m this century, and the Roman

Catholic Church

Under such conditions which Crane (1976) characterizes

as having an independent reward system, competition ts

regulated by a small academy of elder peers who evaluate

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

6

and reward new recruits and junior members through a set

of career stages. Thus, individuals compete only with others

at their own level, and there is increasing security with each

step up the ladder.

While academies espouse a single orthodoxy, disputes,

alternative interpretations, and factions regularly arise with-

In the elite peer group. These have profound effects on

the patterns of competition because senior academy mem-

bers coach, protect, and reward those junior peers who

support their particular position.

Such vertically bonded chains of sponsors and clients

have been observed in the full range of professional and

academic systems (Hall, 1948; Lipset et al, 1 956; White and

White, 1965; Podhoretz, 1968; White, 1970; Clark, 1973;

Blume, 1974; Zuckerman, 1977). Among sociologically ori-

ented scholars at least, the metabolism of schools has not

been well studied. Most work has focused on the process of

establishing academies (Clark, 1973; Adler, 1979) or their

demise (White and White, 1965) rather than on the conse-

quences they have for competition, and the influences they

have on the quality of production. It seems plausible,

however, that each of the schools within an academy may

function much like a simplex (see especially Clark’s [1973]

discussion of the establishment of sociology in the Nine-

teenth Century French academic world).

CIRCLES

If schools evolve In the context of academic orthodoxy,

quite a different form of organization develops where there

is open-market competition over the very nature of the work

to be produced. The paradigmatic situation of this sort is the

avant-garde marketplace for art and literature which re-

placed the academic system m the latter half of the nine-

teenth century (White and White, 1965)

1-i this increasingly faddish art world, competing to more

completely overturn convention became the mark of crea-

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

7

tive excellence (Guerard, 1966; Adler, 1975; Becker, 1978).

A set of interests, including dealers, critics, museums,

patrons, galleries, and scholars developed m this hyper-

competitive art world to merchandise, evaluate, advertise,

and explain &dquo;the new&dquo; (White and White, 1965; Rosenberg

and Fliegel, 1965; Shapiro, 1976; Walters, 1978, Zolberg,

1980). Parallel periods of competition among ideas penodi-

cally occur in science, politics, and religion (Heirich, 1974)

when, for one reason or another, the fundamental premises

of routine work are successfully challenged.

When the institutional supports of any conventional sys-

tem fall, each creator must compete for attention with all

others, but as McHugh (1966)has observed, where there

are so many competitors each may feel a shared fate with

those around and share information, ideas, and emotional

support. Such links tend to coalesce into the sort of network

which Kadushm (1976) calls the &dquo;circle.&dquo;

He characterizes the circle as having no clear boundary

because each member knows some, but not all others. Cir-

cles have no clear criteria of achievement, and so they have

no agreed ranking of members. The circle may have one or

more regions of greater interaction, but there are no officers

and no formal rules. Such networks are typically associated

with a particular place of congregation, a cafe, a gallery,

theatre group, political club, publishing firm, or neighbor-

hood (Naughton, 1979).

The circle of French impressionist painters (White and

White, 1965; Rogers, 1970), literati of the Bloomsbury

group (Arney, 1978; Morgan, 1978; Edel, 1979), and the

scientists responsible for developing recent models of gene-

tic structure (Watson, 1969) have received the most atten-

tion ; but numerous other circles among painters (Ridgeway,

1978), politicians (Wyszomlrskl, 1979), scientists (Crane,

1972; Mullins et al., 1977), and writers (Nelson, 1971 ) have

been identified

Typically, circles are like social movements Beginning as

loose confederations of competitors, they evolve a perspec-

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

8

tive, theory, method, or style which is in opposition to the

established conventions. Most of these groups fail, but

some few succeed in the marketplace for symbolic products.

Success may be due to any one of a number of extrinsic

factors having little to do with aesthetics (Walters, 1978) or

scientific merit (Fleck, 1979), but once established, the

circle is attacked by fledgling movement/circles. Observing

a generation of rock music, Melly (1971) identifies such an

evolution from what began as an anguished revolt against

the established forms of popular music, but which with

success became a mere style, and was in turn attacked by a

younger generation of rock artists.

Circles seem to flourish where there is near perfect

competition and no stable or clear criteria for success. A

circle succeeds insofar as it is able, for awhile, to provide

such criteria. But in a marketplace thirsting for new prod-

ucts, they cannot succeed for long. As Adler (1976) notes,

the process that continually seeks innovation in art works,

as surely makes individual artists obsolete.

BROKERAGE

The hyper-competitive environment which produces cir-

cles can also produce quite different forms of association, if

conditions are changed slightly. Recall that circles develop

in a competitive market, one where there are many persons

competing to provide services, no one group controls the

definition of quality, and there are many purchasers of

services.

If there are many sellers but only a few large buyers, the

market is called oligopsonistic. In such a market, forms of

association quite different from the circle tend to emerge.

The simplex is found in an oligopsonistic market, but so is a

form of association that splits rather than brings together

competing peers. This is the system of &dquo;brokerage.&dquo;

Many types of commercial artists employ personal bro-

kers to help them find buyers for their works or labor. The

title for these persons is usually &dquo;agent.&dquo; The literary agent

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

9

has the oldest and most highly developed tradition among

brokers of talented persons in Western society (Madison,

1974; Powell, 1978). Actors (Steiner, 1977; Friedman,

1978), singers, entertainers, commercial photographers

(Rosenblum, 1973), and Illustrators usually employ agents.

Publishers sometime serve commercial songwrrters m much

the same capacity (Rumble, 1980).

In common, these agent-brokers keep abreast of the

needs of buyers and they coach their client-artists on the

best way to present their talents or products. They serve

the buyer by, in effect, prescreemng the numerous competi-

tors who would otherwise besiege purchasers. The broker

vouches for the technical competence and the social relia-

bility of the craftsperson.

The agent, in turn, relieves the craftsperson of the need to

seek out buyers and &dquo;sell&dquo; his/her work. Thus, the agent

makes possible an exchange of money for services and

products between two incompatible worlds, the one of

universalistic profit-seeking and the other of egotistic/artis-

try (DiMaggio, 1977).

While they facilitate the flow across these boundaries,

agents go to great lengths to prevent direct communication

between buyers and craftpersons or among craftspersons-

such contacts would greatly reduce the need for an agent.

Simpson (1978) describes the world of contemporary fine

art painters in the Soho district of New York these terms. m

Rather than relate primarily with other artists, forming

circles, or link directly with buyer-patrons, as earlier gener-

ations of New York painters had done (Rosenberg and

Fliegel, 1965; Bystryn, 1978), the successful among these

visual artists are oriented primarily to the dealers who run

commercial galleries. These dealers place artists under

exclusive contract, advise them on what to produce, and

show their work to influential private buyers and museums

whose support brings notoriety and financial success.

Brokers are also found at the blue collar level where the

need for unskilled labor is irregular The shape-up of day

workers as stevedores working on the waterfront, and labor

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

10

contractors among migrant farm workers

are two cases in

point (Peterson, 1973). In form, these brokers perform the

same services as the agents discussed above. They bring a

klnd of order and predictability to an otherwise chaotic

market for labor.

In all these cases where brokers play a crucial role in an

oligopsonistic market, the producers-peers seem to have

lost most of their control over the definition of the quality of

their work. In this regard, the broker system contrasts most

sharply with the academy system described above where

the peer group alone is arbiter of quality (Hagstrom, 1965;

Crane, 1976). The musicians’ simplex stands between these

two extremes. The marketplace success or failure of phono-

graph records is the final test of the product, but the peer

group rather than agents or producers certifies the com-

petence of Individual performers (Faulkner, 1971, 1976;

Peterson and White, 1979).

PEER SYSTEMS COMPARED

We have reviewed four sorts of competitive situations

among peers and found that the simplex emerges in only

one of these. If controls over the definition of, and reward

for, excellence is in the hands of the peer group, academies

and schools emerge. If these factors are located m an

avant-garde marketplace, circles emerge. Where middlemen

can interpose themselves to make evaluations, a brokerage

system emerges. From this review, together with the evi-

dence of the musician study, It is now possible to suggest

the boundary conditions for the emergence of the simplex.

The simplex emerges In conditions mandating perfect

competition among peers In which the definition of the

quality of work IS made by the purchases of services, but the

peer group IS able to control the definition of the proficiency

of Its members and would-be members

In this sense, the simplex stands between the school and

the circle While the school controls the definition of quality

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

11

work and the proficiency of workers, the circle tries but does

not control either for long. In the brokerage system, as in the

simplex system, the peer group does not control evaluations

of the quality of product. In the brokerage system the

dealer-broker screens producers, while in the simplex sys-

tem it is the peer group which evaluates and ranks itself.

Having stated the conditions necessary for the emer-

gence of the simplex, and having shown what different

sorts of informal structures, ranging from schools to broker-

age systems, emerge when one or more of these conditions

are not present; we will now seek out situations beyond the

music recording studio where structures like the musicians’

simplex are found.

INDIVIDUALS FORMING SIMPLEXES

Several commentators have noted that research in organ-

izations has tended to focus either on the foibles of formal

organization or on the behavior of individuals within formal

organizations (Burns, 1955; Tichy, 1973; Peterson and

White, 1977). The recurrent structure of Informal organiza-

tion has received scant attention.

For example, the contemporary way of producing movies

and television shows, which brings together many sorts of

freelance technical experts for short periods of time, seems

to have the requisites of simplex formation, but the available

literature, both technical and popular, only hmts at their

presence. Instead, these works take either an individual, or

organizational perspective m research on directors (Cantor,

1971), musicians (Faulkner, 1971), scriptwriters, composers,

stuntmen (Stump, 1970), or on the full range of occupation-

al media occupations (Shanks 1976; Burns, 1977). It is

almost as if informal meant aformal. Given the foci of past

research, it is understandable that our search of the litera-

ture for examples of simplexlike structures has been only

partially successful. Perforce then, we must rely on tenta-

tive inferences as much as on solid case studies.

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

12

Alan Mazur has suggested in private correspondence

that the simplex may be found among some professional

athletes-and is most easily seen among those in individual

competition, such as race car drivers or tennis and golf pros.

The first author knows from personal experience that pro-

fessional sailboat racers, persons who compete against

amateurs and each other in regattas while working for a

boat builder or sailmaker, do form a set of overlapping

simplexes. Even white competing with each other, they

monitor fair play (which is often quite different from follow-

ing the rules) within their own ranks, they exchange many

tips on techniques, and they act quite blatantly to prevent

undesired rivals from joining their ranks.

Research on organized crime, more than research on any

other context, has shown the operation of simplical struc-

tures. In the realm of organized crime, a market of perfect

competition, with its attendant high rates of violence, is

rationalized by a small group of criminals who coalesce into

invisible families to protect each other and eliminate rivals.

While ethnic inspiration (Blok, 1974; Light, 1977), the

conception of &dquo;family&dquo; is sociological not biological (lanni,

1972, 1974; Brown, 1976).

While the violent death or deposition of a family-head

occasions the greatest newspaper coverage, these studies

document numerous parallels to the structure and func-

tioning of the musicians’ simplex. These parallels extend

even to the destabilizing consequences of technology, and

the introduction of new sorts of products. Much as the

introduction of new musical styles and new techniques of

record-making make it possible for rival simplexes to suc-

cessfully challenge the established musicians, likewise, the

introduction of new drug sources and new means of import-

ing drugs have allowed rival gangs to successfully chal-

lenge the existing system (Cannon, 1979).

Simplexes may operate at two levels in the world of

organized crime. In addition to the simplexes formed of

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

13

individuals bonded together as families, there may be a

higher-order simplex in the world of crime

well. Since as

there is a continual threat that each family will compete

with the others to increase its sphere of criminal activity,

the heads of families have, more or less successfully,

combined in a simplex of simplexes to arbitrate rivalries

among families, collectively keep out nonmembers, and

negotiate with the authorities about the permissible scope

of illegal activity.

Some of the literature on the American ruling class

suggests that this may be a fertile arena in which to look for

simplexes. Whatever else it may be or do, the ruling class

elite is a set of competing peers who do cooperate to

maintain their established position (Baltzell, 1958, 1964).

There are numerous studies of clique-formation which

operate through formal associations, such as corporations

and banks (Allen, 1974; Mariolis, 1975; Miller, 1978), or

cultural organization boards of directors (Meyer, 1979;

Steine, 1979). Links are also cemented through fraternal

associations such as the secret societies at Yale (Rosen-

baum, 1977), recreational associations such as the Bohemi-

an Grove in northern California (Domhoff, 1974; Kramer,

1977) and political groups in Washington (Bonacich and

Domhoff, 1978) and cultural institutions (Useem, 1979).

When examined in detail, many of these are not so much

tight groupings of rival peers as they are loose collections

who have different resources and skills which they hope to

pool for mutual benefit. In form, these groups look less like

simplexes and more like circles as described above Sim-

plexes seem more likely to emerge m segments of the ruling

class which are discriminated against for reasons of region,

religion, or ethmoty. Their cultural homogeneity is not only

the basis of discrimination against them, but IS also the

basis for defining a tightly bounded simplex structure

Birmingham, (1976) provides an excellent case in point In

his study of the rise and flowering of the German Jewish

elite In New York City between 1837 and 1929

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

14

Numerous situations m which individuals compete might

be examined for simplex-formation, but this part of the

presentation will conclude with one final illustration, which

is drawn from the animal world. Studies have long noted

the existence of hierarchical pecking-orders within a num-

ber of different species of mammals and birds living m close

proximity. These hierarchical arrangements make for a

continuing low level of tension but greatly reduce the

frequency of senous violence among band members All

captive and most free-living primate bands of any size show

some degree of hierarchy at least among adult males.

Serious threats and fighting tend to occur only between

animals of adjacent or nearly adjacent ranks.

Hall and DeVore (1965), however, report that among

some baboon bands the high ranked males exhibit another

sort of behavior. When any of their number is attacked by an

outside baboon, all the rest of the high ranking baboons

attack the rival In unison. Using this collective self-defense,

the dominant group members are able to keep their high

rank collectively long after their individual fighting ability

has waned. Imanlshi (1963) and Kaufman (1967) report

similar patterns of collective self-defense among the domi-

nant males of Japanese macaques and rhesus monkeys.

Why does the simplical structure emerge among some, but

not all band-living monkeys and apes (Kaufman 1967;

Chance and Jolly, 1970)? Answers to these questions may

provide clues to the process of simplex-formation among

humans (Masur, 1973).

GR~r~ ~ TE S FORMING SIMPLEXES

If individuals of the species may find themselves compet-

ing, so may organizations of various sorts. There are numer-

ous situations m which organizations of like kind combine to

form associations of the simplical sort.

Near-perfect competition has characterized the early

stages of almost every industry in the United States. Over

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

15

time, the less successful firms are eliminated or absorbed,

but perfect monopoly ts not reached due, m large part, to the

operation of federal anti-trust legislation (Pffeffer and Sala-

nik, 1978; Aldrich, 1979). Instead the market comes to be

dominated by a few firms. The auto industry IS a classic case

in point (Scherer, 1970; Vernon, 1972).

The evolution toward oligopolistic markets has been most

often noted in manufacturing and consumer services (Ver-

non, 1972), but at the local level the same process can be

observed in professional service industries as well. MacRae

(1978) has shown how the leading law firms of a city

operate m concern to divide up the most desirable law work

leaving the more risky, declasse, and low profit work to the

marginal firms, partnerships, and solo lawyers.

Much the same process has been described for social

welfare agencies of another city by Gerald Hage (m private

communication). The various agencies did not compete m

the 1950s. Each had a well-defined niche, receiving money

from and servicing a special community defined along

religious and ethnic lines. Intense competition came with

the infusion of large amounts of Federal &dquo;war on poverty&dquo;

money in the mid-1960s. When last observed m 1970,

competition was again muted. A slightly altered set of

agencies worked together to jointly lobby for increased

welfare funding and to shut out the competition from other

agencies.

This cycle of oligopoly followed by competition, followed

in by reenollgopollzatlon has been charted by Peterson

turn

and Berger (1975) In the commercial music mdustry. The

trend toward greater concentration in the music mdustry

has been due in part to the actions of the firms m competi-

tion with each other, but the leading firms also cooperate m

various ways to reduce the competition from rising indepen-

dent firms. For example, the leading firms have manipulated

fears about immorality in music to reduce competition from

the more free-wheeling independents (Leonard, 1962;

Sanjek, 1972). And a similar tactic has been used at some

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

16

time or another in each of the commercial entertainment

industries, including movies, comics, radio, and television

(Peterson, 1976). The manipulation of capital, patents,

government regulations, and pricing policies among the few

leading firms to etiminate competition has been best de-

tailed in the case of the pharmaceutical industry (Murray,

1974; Hirsch, 1973; Peterson, 1980).

In the field of international business, combinations of

leading producers can be more explicit and formalized

because there are no anti-trust regulations. The oit cartel,

OPEC, is just the most consequential of many simplexlike

cartels. They take many forms, ranging from the DeBeers

interests who control the world’s supply of fine diamonds

(Gibson, 1979) to CERT, the organization of American

Indian tribes which controls lands with fuel deposits.

Not-for-profit organizations often cooperate to reduce

competition for scarce resources and promote common

interests as we have already seen for the case of welfare

agencies above. The National Collegiate Athletic Associa-

tion (Stern, 1979) and the World Council of Churches

(Heirich, 1974) have recently been studied from this per-

spective.

In all these competitive spheres of organizational action,

something like the simplex seems to emerge, Groupings of

like-type organizations form to reduce competition between

members and cooperate toward common goals. The degree

to which these simplexes of organizations actively operate

to prevent or discourage rival nonmembers is not clear in all

cases (Heirich, 1974), but is dramatically strong where it

has been a focus of attention (Peterson and Berger, 1975;

Sanjek, 1972; Stern, 1979).

Some of the combinations of organizations just discussed,

notably OPEC, the NCAA, and the World Council of Churches,

have become formally constituted organizations seeking

public legitimacy. As they do so, they can incorporate more

members and exercise social control through formal mech-

anisms. And yet, informal means of control continue to be

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

17

quite important as well (Stern, 1979); just as many of the

mechanisms of control within secret college societies con-

tinue to operate when the groups become formalized as

fraternities and sororities (Rosenbaum, 1977). lf informal

mechanisms are used within formal organizations, IS there

any utility in looking for the simplex m such structures? This

is the question to which we turn m focusing again on

Individuals rather than organizations as the units of analy-

sis.

IMBEDDED IN ORGANIZATIONS

Persons at the same organizational level do not compete

with each other in a market context. Nevertheless, organi-

zations are usually structured so that employees do com-

pete for favorable evaluations, promotions, and pay raises.

When evaluation IS clearly individualized, as in the case of

executives, the competition-reducing patterns of associa-

tion tend to link individuals vertically (White, 1970; Blau,

1977; Kanter, 1977; Wyszomirski, 1979). When evaluation

and sanction are shared more or less equally by entire

groups, however, peer groups tend to predominate. Exam-

ples of peer-bonding include blue collar work groups (Whyte,

1949; Roy, 1952; Babchuk and Goode, 1951), enlisted men

m combat (Shils and Janowitz, 1948; Little, 1964; Shibu-

tanl, 1978), and prisoners (Sykes and Messinger, 1960).

Only m the latter situation do peer groups resemble the

simplex. Only In prison do the more powerful men band

together for their mutual benefit against the other prisoners

and the prison administration Perhaps this is not surprising

because prisoners are involuntary organization members

and the mmate &dquo;community&dquo; IS more nearly m the condition

of competition than are any other organization-peer groups

which have been studied.

Why has the simplex not been identified imbedded In

formal organization? Two possibilities suggest themselves.

It may be that researchers have not looked for the simplex,

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

18

and It may be that it is not there. We have traced the

patterns of research on organizations, suggesting that 60

years of empirical work, diverse as it surely is, has focused

on formal organization and the short-run accommodations

individuals make to rule-based organizations (Peterson and

White, 1977). The relatively few studies that have examined

the form of Informal organization see it as shaped by outside

forces, such as the operation of formal rules (Shils and

Janowitz, 1948), individual careers (Hall, 1948; Kanter,

1977), machine technology (Sayles, 1958), or episodes in

organizational politics (Burns, 1955). It may be that the

structunng consequences of formally constituted complex

groups may be so great that the simplex form does not

survive. If so, the simplex may literally be alternative to

complex organization.

ELEMENTS OF SIMPLEX STRUCTURE

This review has ranged widely in order to assay both the

characteristics and the extent of the simplex. Given the

state of the literature, the question of its extent is still very

much open. The scattered reports on informal groups in

occupations and in organizations, however, are suggestive.

With this wide range of information to temper and sup-

plement the observations made in the study of the musi-

cians’ simplex, it is possible to identify seven characteristics

which seem to be common to all simplexes. These are:

(1) The simplex is an informal group that functions without a

constitution, officers, or any of the normal trappings of for-

mal or complex organizations-thus the name &dquo;simplex&dquo; is

used to counterpose it to &dquo;complex&dquo; organization.

(2) A simplex is composed of a small set of peers who know

each other personally They assess and rank each others’

ability while acclaiming their collective excellence relative

to all nonmembers

(3) Simplex members discipline and reward each other through

gossip and the exchange of favors

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

19

(4) Simplex members seek to control the relevant people m the

task environment by shaping the flow of information both

about how the job can best be done, and also about the abil-

ity of persons inside and outside the simplex to satisfactor-

ally perform the work

(5) The simplex is a set of mechanisms for rejecting, recruiting,

and rewarding prospective members so that most aspirants

support, rather than challenge, the simplex

(6) Simplex structures are surprisingly stable, some surviving

for more than a decade with a gradual but complete turnover

membership.

in

(7) Although powerful and long-lasting, simplexes remain in-

visible to most observers. What is ordinarily seen is individ-

ual acts of ranking, favors, and contacts while the collective

nexus we call the simplex goes unobserved.

Our quest, which begun with observations of the unanti-

cipated cooperation among recording studio musicians, has

led us both far and wide. From the evidence of the journey,

the simplex form of association emerges only in rather

special environing conditions. At the same time, there are

numerous signs that these conditions can be found not only

among some individuals in competition, but also among

firms in an industry, organizations in a market, and even

groups of nations.

Above all, this review highlights the need for more careful

comparisons of the numerous sorts of groupings such as

circles, schools, simplexes, and the like. Together they may

well form a class of associations standing between the

intimate primary group and the formal rule-conditioned

complex organization. While large numbers of case studies

can be cited, the systematic charting of this fascinating

domain has hardly begun.

REFERENCES

ADLER, J (1979) Artists In Offices An Ethnography of an Academic Art Scene

New Brunswick, NJ Transaction Books

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

20

——— (1975) "Innovative art and obsolescent artists." Social Research 42,

(Summer): 360-378.

ALDRICH, H. (1979) Organizations and Environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pren-

tice-Hall.

ALLEN, M. P. (1974) "The structure of interorganizational elite cooptations: Inter-

locking corporate directorates." Amer. Soc. Rev. 39 (June): 393-406.

ARNEY, A. (1978) "The lost generation: the dynamics of a circle." Nashville, Ten-

nessee (unpublished)

BABCHUK, N. and W. J. GOODE (1951) "Work incentives in a self-determined

group." Amer. Soc. Rev. 16 (October): 679-687.

BALTZELL, E. D. (1964) The Protestant Establishment. New York: Random House.

(1958) Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class.

———

New York: Macmillan.

BECKER, G. (1978) The Mad Genius Controversy: A Study in the Sociology of Devi-

ance. Beverly Hills: Sage.

BIRMINGHAM, S. (1976) Our Crowd: The Great Jewish Families of New York. New

York: Harper & Row.

BLAU, P. (1977) Inequality and Heterogeneity. New York: Macmillan.

BLOK, A. (1974) The Mafia of a Sicilian Village, 1860-1960. New York: Harper &

Row.

BLUME, S. S. (1974) Toward a Political Sociology of Science, New York: Mac-

millan.

BONACICH, P. and G. W. DOMHOFF (1978) "Overlapping memberships among

clubs and policy groups of the American ruling class." (unpublished)

BROWN, R. H. (1976) "Reminiscence of a friend of friends: a document for the his-

torical sociology of crime." (unpublished)

BURNS, T. (1977) The BBC: Public Institution and Private World. New York: Holmes

& Meier.

(1955) "The reference of conduct in small groups: cliques and cabals in

———

occupational milieux." Human Relations 8 (November): 467-486.

BYSTRYN, M. (1978) "Art galleries as gatekeepers: the case of the abstract im-

pressionists." Social Research 45 (Summer): 392-412.

CANNON, L. (1979) "Illicit drugs pour in via ’crazy’ Colombians." Washington Post

(August 13): 1, 15.

CANTOR, M. G. (1971) The Hollywood TV Producer: His Work and His Audience.

New York: Basic Books.

CHANCE, M. R. and C. JOLLY (1970) Social Groups of Monkeys, Apes and Men.

New York: Dutton.

CLARK, T. M. (1973) Prophets and Patrons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press.

CRANE, D. (1976) "Reward systems in art, science, and religion," pp. 57-73 in R.

A. Peterson (ed.) The Production of Culture. Beverly Hills: Sage.

———

(1972) Invisible Colleges. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

DENICH, B. (1978) "The social side of socialism." Human Behavior (May): 30-38.

DiMAGGIO, P. (1977) "Market structure, the creative process, and popular cul-

ture," J. of Popular Culture 11, (Fall): 433-451.

DOMHOFF, G. W. (1974) The Bohemian Grove: A Study of Ruling-Class Cohesive-

ness. New York: Harper & Row.

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

21

EDEL, L (1979) Bloomsbury A House of Lions Philadelphia J B Lippincott

FAULKNER, R R. (1976) "Dilemmas in commercial work"Urban Life 5 3-32.

(1971) Hollywood Studio Musicians Chicago AVC

———

FISCHER, C S. (1977) Networks and Places Social Relations in the Urban Setting

New York Macmillan

FLECK, L. (1979) Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact Chicago Univ of

Press

Chicago "

FRIEDMAN, N (1978) "The Hollywood actor’s search for work Presented at the

meetings of the American Sociological Association

GIBSON, P (1979) "DeBeers: can a cartel be forever?" Forbes (May 28) 45-56

GRANOVETTER, M S (1974) Getting a Job A Study in Contacts and Careers

Cambridge, MA Harvard Univ Press

GUERARD, A L (1966) Art for Art’s Sake New York Schocken

HAGSTROM, W (1965) The Scientific Community New York Basic Books.

HALL, K R.L. andI DeVORE (1965) "Baboon social behavior," in I. Devore (ed ) Pri-

mate Behavior. New York. Holt, Rinehart & Winston

HALL, O (1948) "The stages of a medical career "Amer J of Sociology 53 (March).

327-336

"

HEIRICH, M (1974) "The sacred as a market economy Presented at the meetings

of the American Sociological Association

HIRSCH, P M (1973) "The organization of consumption "Ph D dissertation, Uni-

versity of Michigan.

IANNI, F A J. (1974) Black Mafia. New York Simon & Schuster

(1972) A Family Business Kinship and Social Control in Organized Crime

———

New York Russell Sage

IMANISHI, K (1963) "Social behavior in Japanese monkeys," pp 68-81 in C

Southwick (ed ) Primate Social Behavior Princeton Van Nostrand.

KADUSHIN, C. (1976) Networks and circles in the production of culture," pp 107-

122 in R. A. Peterson (ed ) The Production of Culture Beverly Hills Sage

(1975) "Introduction to the sociological study of networks " (unpublished)

———

Columbia University

KANTER, R M (1977) Men and Women of the Corporation New York Basic Books

KAUFMAN, J H. (1967) "Social relations of adult males in a free ranging band of

rhesus monkeys" pp 73-98 in S Altman (ed ) Social Communication Among

Primates Chicago Univ of Chicago Press

KRAMER, L (1977) "Bohemian Grove—where big shots go to camp " New York

Times (August 14) F3

LEONARD, N (1962) Jazz and the White Americans Chicago Univ of Chicago

Press.

LIGHT,I (1977) "The ethnic vice industry, 1880-1944 " Amer Soc Rev 42 (June)

464-479

LIPSET, S M , M TROW, and J COLEMAN (1956) Union Democracy New York

Macmillan

LITTLE, R W (1964) "Buddy relations and combat performance," pp 195-223 in

M Janowitz (ed ) The New Military New York Russell Sage

MacRAE, T A (1978) "Controlling the market for legal services in a mid-South

"

city Nashville, Tennessee (unpublished)

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

22

McHUGH, P. (1966) "Structured uncertainty and its resolution the case of the pro-

fessional actor " Amer Soc Rev. 31 (April) 208-217.

MADISON, C A (1974) Irving to Irving. Author-Publisher Relations, 1800-1974.

New York Bowker

MARIOLIS, P (1975) "Interlocking directorates and control of corporations." So-

cial Sci 56 (December) 425-439

MASUR, A (1973) "A cross-species comparison of status in small established

groups." Amer. Soc Rev. 38 (October) 513-530.

MELLY G (1971) Revolt into Style The Pop Arts New York Doubleday.

MEYER, K E (1979) The Art Museum Power, Money, Ethics New York Morrow

MILLER, J. (1978) "Interlocking directorates flourish " New York Times (April 23)

MORGAN, D H J. (1978) "Patronage the case of the Bloomsbury circle" Pre-

sented at the Conference on Culture of the British Sociological Association,

April

MULLINS, N C, L L HARGENS, P. K. HECT, and E L. KICK (1977) "The group

structure of cocitation clusters a comparative study " Amer Soc Rev 42 (Au-

gust) 552-562 "

MURRAY, M J (1974) "The pharmaceutical industry a study in corporate power

Int J of Health Services 4 (September) 625-640

NAUGHTON, F. (1979) "Greenwich Village 1913 everyday actions and formation

of an artistic/intellectual community " Presented at the Sixth Annual Social

Theory and the Arts Conference, Patterson, N J , April

NELSON, J G (1971) The Early Nineties Cambridge, MA Harvard Univ Press.

PETERSON, R A (1980) "Entrepreneurship in organization," in P C Nystrom and

W H Starbuck (eds ) Handbook of Organizational Design. New York Oxford

Univ Press

(1976) "Art and government " Society 14 (November) 58-59.

———

(1973) The Industrial Order and Social Policy Englewood Cliffs, NJ Pren-

———

tice-HallII

and D G BERGER (1975) "Cycles in symbol production the case of popular

———

music " Amer Soc Rev 40 (April) 158-173.

PETERSON, R A and H G. WHITE (1979) "The simplex located in art worlds "Ur-

ban Life 7 (January) 411-439

(1977) "Simplex the form of informal organization" Presented at the

———

meetings of the American Sociological Association, September

PFFEFER, J and G R SALANIK (1978) The External Control of Organizations New

York Harper & Row

PODHORETZ, N (1968) Making it New York Random House

POGGIOLI, R (1968) The Theory of the Avant-Garde Cambridge, MA Belknap

POWELL, W W (1978) "Publishers’ decision-making what criteria do they use in

deciding which books to publish?" Social Research 45 (Summer) 227-252

RIDGEWAY, S (1978) "Artist cliques, gate-keepers, and structural change " Pre-

sented at the meetings of the American Sociological Association

ROGERS, M (1970) "The Batignolles group creators of impressionism," pp 194-

220 in M C Albrecht, J H Barnett, et al (eds) The Sociology of Art and Litera-

ture New York Praeger

ROY, D (1952) "Quota restriction and goldbricking in a machine shop " Amer J.

of Soc 57 (March) 427-442

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

23

"

ROSENBAUM, R (1977) "The last secrets of skull and bones Esquire (Septem-

ber) 85-89, 148-150

ROSENBERG, B and N FLIEGEL (1965) The Vanguard Artist Portrait and Self-

Portrait Chicago Quadrangle

ROSENBLUM, B (1973) "Photographers and their photographs an empirical stu-

"

dy in the sociology of asthetics Ph D dissertation, Northwestern University

"

RUMBLE, J (1980) "Fred Rose and the development of publishing in Nashville

Ph D dissertation, Vanderbilt University

SANJEK, R (1972) "The war on rock"Downbeat Annual 28-32

SAYLES, L R (1958) Behavior of Industrial Work Groups New York John Wiley

SCHERER, F M (1970) Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance

Chicago Rand McNally

SHANKS, B. (1976) The Cool Fire How to Make it in Television New York Vintage

SHAPIRO, T (1976) Painters and Politics New York Elsevier North-Holland

SHIBUTANI, T (1978) The Derelicts of Company K Berkley Univ of California

Press

SHILS, E A and M JANOWITZ (1948) "Cohesion and disintegration in the Wehr-

"

macht

World War II Public Opinion Q 12 (Summer) 280-315

in

SIMPSON, C R (1978) "Soho a residential-occupational community in Lower

Manhattan " Ph D dissertation, New School for Social Research

STEINER, S (1977) "Robert King—the king of commercial actors"New York

Times (August 14)

STEINE, R (1979) "Interlocking directorates among Nashville’s cultural organiza-

"

tions Vanderbilt University (unpublished)

STERN, R N (1979) "The development of an interorganizational control network

the case of intercollegiate athletics " Admin Sci 24 (June) 242-266

STUMP, A (1970) "What became of the wild bunch " TV Guide (November 14)

16-19

SYKES, G M and S L MESSINGER (1960) "The inmate social system," pp 5-19

R A Cloward (ed ) Theoretical Studies in Social Organization of the Prison

in

New York Social Science Research Council

"

TICHY, N (1973) "An analysis of clique formation and structure in organizations

Admin Sci Q 18 (June) 194-208

USEEM, M J (1979) "The social organization of the American business elite and

participation of corporation directors in the governance of American institu-

tions " Amer Soc Rev 44 (August) 553-572

VERNON, J M (1972) Market Structure and Industrial Performance Boston Allyn

& Bacon

WALTERS, B R (1978) "The politics of esthetic judgment" PhD dissertation,

State University of New York, Stony Brook

WATSON, J D (1969) The Double Helix New York New American Library

WHITE, H (1970) Chains of Opportunity Cambridge, MA Harvard Univ Press

and C A WHITE (1965) Canvases and Careers Institutional Change in the

———

French Painting World New York John Wiley

WHYTE, W F (1949) "The social structure of the restaurant " Amer J of Sociology

54 (January) 302-314

WYSZOMIRSKI, M (1979) "Presidential advisory circles toward a theory of re-

cruitment " Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science

Association, Washington, D C

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

24

ZOLBERG, V. (Forthcoming) "Displayed art and performed music " Soc. Q

ZUCKERMAN, H. (1977) Scientific Elites New York Macmillan

RICHARD A PETERSON, an industrial sociologist at Vanderbilt University inter-

ested in the production of culture, has researched genres of commercial music

ranging from jazz to disco, and is currently completing a monograph on the

commercialization of country music m Nashville A year’s research leave with the

Research Division of the National Endowment of the Arts has opened a line of

research dealing with contemporary American lifestyles and patterns of cultural

choice

HOWARD G WHITE is Professor of Sociology and Social Science at Chicago City-

Wide College of the City Colleges of Chicago He received his master’s from

Columbia University and his doctorate from the University of Kansas Continuing

his investigation of &dquo;simplex structures,&dquo; at present, he is undertaking a study of

Chicago chefs

Downloaded from jce.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on March 11, 2015

You might also like

- Group 3 - Online Marketing Big Skinny - Case AnalysisDocument5 pagesGroup 3 - Online Marketing Big Skinny - Case AnalysisNitin BhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Di Maggio Classification in ArtDocument17 pagesDi Maggio Classification in ArtOctavio LanNo ratings yet

- The Passion of James Valliant's CriticismDocument81 pagesThe Passion of James Valliant's Criticismneil.parille4975100% (8)

- Baumann A General Theory of Artistic LegitimationDocument19 pagesBaumann A General Theory of Artistic LegitimationTeorética FundaciónNo ratings yet

- Trustees of Culture: Power, Wealth, and Status on Elite Arts BoardsFrom EverandTrustees of Culture: Power, Wealth, and Status on Elite Arts BoardsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Introduction To "Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis"Document5 pagesIntroduction To "Critical Transnational Feminist Praxis"CaitlinNo ratings yet

- The Science of Synthesis: Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems TheoryFrom EverandThe Science of Synthesis: Exploring the Social Implications of General Systems TheoryNo ratings yet

- PETERSON, R A The Production of Culture A ProlegomenonDocument16 pagesPETERSON, R A The Production of Culture A ProlegomenonNatália FrancischiniNo ratings yet

- Genesis, Creation and Early Man The Orthodox Christian VisionDocument728 pagesGenesis, Creation and Early Man The Orthodox Christian VisionKarsten Rohlfs100% (3)

- IATF 16949-2016 Intro and Clauses PDFDocument274 pagesIATF 16949-2016 Intro and Clauses PDFneetuyadav2250% (2)

- Cycles in Symbol Production - The Case of Popular Music PDFDocument17 pagesCycles in Symbol Production - The Case of Popular Music PDFLaura PinzónNo ratings yet

- AntropologDocument35 pagesAntropologXaviNo ratings yet

- A General Theory of Artistic Legitimation How Art Worlds Are Like Social MovementsDocument19 pagesA General Theory of Artistic Legitimation How Art Worlds Are Like Social MovementsAgastaya ThapaNo ratings yet

- 04.22 Strauss 78Document10 pages04.22 Strauss 78Eduardo Vega CatalánNo ratings yet

- Peterson y Berger. Cycles in Symbol ProductionDocument17 pagesPeterson y Berger. Cycles in Symbol ProductionJuan Camilo Portela GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The The The: Understanding Third Sector: Revisiting Prince, The Merchant, CitizenDocument17 pagesThe The The: Understanding Third Sector: Revisiting Prince, The Merchant, CitizenaristokleNo ratings yet

- Working Weeks, Rave Weekends: Identity Fragmentation and The Emergence of New CommunitiesDocument25 pagesWorking Weeks, Rave Weekends: Identity Fragmentation and The Emergence of New CommunitiesDragana KosticaNo ratings yet

- Articulating Musical Meaning:Re-Constructing Musical History:Locating The 'Popular'Document40 pagesArticulating Musical Meaning:Re-Constructing Musical History:Locating The 'Popular'Rory PeppiattNo ratings yet

- An Intensive Study of Organizational Culture in Telecom Sector (HR)Document85 pagesAn Intensive Study of Organizational Culture in Telecom Sector (HR)Sudhanshu Roxx100% (5)

- E) Engagement - We Don't Exclude The K But Policy Relevance Is Key To Change Campbell, 02Document8 pagesE) Engagement - We Don't Exclude The K But Policy Relevance Is Key To Change Campbell, 02yesman234123No ratings yet

- Chapter 6. Groups and OrganizationsDocument31 pagesChapter 6. Groups and OrganizationseliasNo ratings yet

- Evan Wendel, "New Potentials For 'Independent' Music: Social Networks, Old and New, and The Ongoing Struggles To Reshape The Music Industry"Document112 pagesEvan Wendel, "New Potentials For 'Independent' Music: Social Networks, Old and New, and The Ongoing Struggles To Reshape The Music Industry"MIT Comparative Media Studies/WritingNo ratings yet

- The Musicological Elite: Tamara LevitzDocument72 pagesThe Musicological Elite: Tamara LevitzJorge BirruetaNo ratings yet

- Petersen Production of Culture PerspectiveDocument26 pagesPetersen Production of Culture PerspectiveDon SlaterNo ratings yet

- Nineteenth-Century Individualism and the Market Economy: Individualist Themes in Emerson, Thoreau, and SumnerFrom EverandNineteenth-Century Individualism and the Market Economy: Individualist Themes in Emerson, Thoreau, and SumnerNo ratings yet

- Article The Production of Culture PerspectiveDocument20 pagesArticle The Production of Culture Perspectivebarterasmus100% (1)

- Ventsel - 2008 - Punx and Skins United One Law For Us One Law For ThemDocument57 pagesVentsel - 2008 - Punx and Skins United One Law For Us One Law For ThemRab Marsekal Atma PinilihNo ratings yet

- Rock Music and The State Dissonance or CounterpointDocument21 pagesRock Music and The State Dissonance or CounterpointJef BakerNo ratings yet

- MARX - Collective Behavior and Social MovementsDocument18 pagesMARX - Collective Behavior and Social MovementsJanelle Rose TanNo ratings yet

- Lamont, Michèle - How To Become A Dominant French Philosopher - The Case of Jacques Derrida PDFDocument39 pagesLamont, Michèle - How To Become A Dominant French Philosopher - The Case of Jacques Derrida PDFBurp FlipNo ratings yet

- Charismatic Capitalism: Direct Selling Organizations in AmericaFrom EverandCharismatic Capitalism: Direct Selling Organizations in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Culture in Interaction - Eliasoph LichtermanDocument61 pagesCulture in Interaction - Eliasoph LichtermanpraxishabitusNo ratings yet

- Popculture BlackonlineDocument5 pagesPopculture Blackonlinezubairbaig313No ratings yet

- American Sociological Association American Sociological ReviewDocument19 pagesAmerican Sociological Association American Sociological ReviewMarcelo Arequipa AzurduyNo ratings yet

- Listening Beyond The Echoes MediaDocument207 pagesListening Beyond The Echoes Mediab-b-b1230% (1)

- Peterson, Anand - The Production of Culture PerspectiveDocument25 pagesPeterson, Anand - The Production of Culture Perspectiveqthestone45No ratings yet

- Chap.9 ShepsleDocument44 pagesChap.9 ShepsleHugo MüllerNo ratings yet

- David D. Laitin - Nations, States, and Violence-Oxford University Press, USA (2007)Document179 pagesDavid D. Laitin - Nations, States, and Violence-Oxford University Press, USA (2007)Hendra MulyanaNo ratings yet

- WhyMutualAid - OpenDemocracy - Whitley With Cover Page v2Document6 pagesWhyMutualAid - OpenDemocracy - Whitley With Cover Page v2peter_yoon_14No ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. American Sociological AssociationDocument3 pagesSage Publications, Inc. American Sociological Associationmi nguyễnNo ratings yet

- Mann, Michael (1970) - The Social Cohesion of Liberal DemocracyDocument18 pagesMann, Michael (1970) - The Social Cohesion of Liberal Democracyjoaquín arrosamenaNo ratings yet

- Act in Music EdDocument30 pagesAct in Music EdHannah Elizabeth GarridoNo ratings yet

- Composing Capital: Classical Music in the Neoliberal EraFrom EverandComposing Capital: Classical Music in the Neoliberal EraRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Heckathorn & Jeffri - Social Networks of Jazz MusiciansDocument14 pagesHeckathorn & Jeffri - Social Networks of Jazz MusiciansUlises RamosNo ratings yet

- Why Do People Sacrifice For Their Nations by Paul SternDocument20 pagesWhy Do People Sacrifice For Their Nations by Paul SternEllaineNo ratings yet

- World System TheoryDocument27 pagesWorld System TheoryLaura RodriguesNo ratings yet

- 205 GRCM PP 1-33Document32 pages205 GRCM PP 1-33loveyourself200315No ratings yet

- Electronic Dance Music Festivals: A Promise of Sex and Transnational ExperienceDocument20 pagesElectronic Dance Music Festivals: A Promise of Sex and Transnational ExperienceDaymon RichardNo ratings yet

- The Post Industrial Society Tomorrow 039 S Social History Classes Conflicts and Culture in The Programmed Society PDFDocument132 pagesThe Post Industrial Society Tomorrow 039 S Social History Classes Conflicts and Culture in The Programmed Society PDFJuan IgnacioNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0304422X11000878 MainDocument22 pages1 s2.0 S0304422X11000878 MainMagdalena KrzemieńNo ratings yet

- Third-Culture Building: A Paradigm Shift For International and Intercultural CommunicationDocument23 pagesThird-Culture Building: A Paradigm Shift For International and Intercultural CommunicationJean SolNo ratings yet

- Thesis Eleven: Durkheimian Cultural Sociology and Cultural StudiesDocument10 pagesThesis Eleven: Durkheimian Cultural Sociology and Cultural Studiesmassive11No ratings yet

- Slobin 1992-Micromusics - of - The - West-A - Comparative - ApproachDocument88 pagesSlobin 1992-Micromusics - of - The - West-A - Comparative - ApproachMarcela Laura Perrone Músicas LatinoamericanasNo ratings yet

- Juris EphemeraDocument20 pagesJuris EphemeraPdeabismoNo ratings yet

- Romance, Irony, and Solidarity Author(s) - Ronald N. Jacobs and Philip SmithDocument22 pagesRomance, Irony, and Solidarity Author(s) - Ronald N. Jacobs and Philip Smithdimmi100% (1)

- 7 Foundations and CollaborationDocument27 pages7 Foundations and CollaborationDaysilirionNo ratings yet

- A World to Win: Contemporary Social Movements and Counter-HegemonyFrom EverandA World to Win: Contemporary Social Movements and Counter-HegemonyNo ratings yet

- Good Work in CompositionDocument25 pagesGood Work in CompositionErica GlennNo ratings yet

- 117024Document31 pages117024James LegrandNo ratings yet

- Economic Freedom and Social Justice The Classical Ideal of Equality in Contexts of Racial Diversity 1St Edition Wanjiru Njoya Full ChapterDocument68 pagesEconomic Freedom and Social Justice The Classical Ideal of Equality in Contexts of Racial Diversity 1St Edition Wanjiru Njoya Full Chaptershirley.pearson976100% (9)

- Reciprocities in HomerDocument40 pagesReciprocities in HomerAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Graffiti Crews Potential: Pedagogical RolΕDocument14 pagesGraffiti Crews Potential: Pedagogical RolΕEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- Scaling the Heights: Thought Leadership, Liberal Values and the History of The Mont Pelerin Society: Thought Leadership, Liberal Values and the History of The Mont Pelerin SocietyFrom EverandScaling the Heights: Thought Leadership, Liberal Values and the History of The Mont Pelerin Society: Thought Leadership, Liberal Values and the History of The Mont Pelerin SocietyNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Ying Guo, Laura M. Justice, Brook Sawyer, Virginia TompkinsDocument8 pagesTeaching and Teacher Education: Ying Guo, Laura M. Justice, Brook Sawyer, Virginia TompkinsFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Ec 6Document77 pagesEc 6Maruthi -civilTechNo ratings yet

- GlowScript Annotations 1Document3 pagesGlowScript Annotations 1robbie_delavega7000No ratings yet

- Transfer-Learning Based Gas Path Analysis Method For Gas Turbines 1-S2.0-S1359431118340638-MainDocument13 pagesTransfer-Learning Based Gas Path Analysis Method For Gas Turbines 1-S2.0-S1359431118340638-MainIbnu SufajarNo ratings yet

- Ramesh and Gargi (A)Document4 pagesRamesh and Gargi (A)anon_533040118No ratings yet

- Artikel SkripsiDocument6 pagesArtikel SkripsiJumi PermatasyariNo ratings yet

- HazardsDocument58 pagesHazardsAshutosh Verma100% (1)

- Conducting Inspections of Building Facades For Unsafe ConditionsDocument8 pagesConducting Inspections of Building Facades For Unsafe ConditionsANo ratings yet

- Volume-I: Uttar Pradesh Jal NigamDocument373 pagesVolume-I: Uttar Pradesh Jal NigamPankaj KumarNo ratings yet

- Manual Plant 4D Athena SP2 - Installation-MasterDocument65 pagesManual Plant 4D Athena SP2 - Installation-Masterjimalt67No ratings yet

- WIM Day 1 GR 3 4 VFDocument3 pagesWIM Day 1 GR 3 4 VFJenonymouslyNo ratings yet

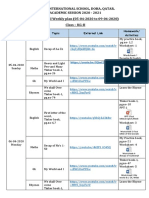

- Loyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIDocument3 pagesLoyola International School, Doha, Qatar. Academic Session 2020 - 2021 Home-School Weekly Plan (05-04-2020 To 09-04-2020) Class - KG-IIAvik KunduNo ratings yet

- National Achievement Survey: P U N J A BDocument60 pagesNational Achievement Survey: P U N J A BHarpreetNo ratings yet

- 2018 Oow PRM 5460 Inv and Wms in The Cloud - 1540851493083001pfjmDocument45 pages2018 Oow PRM 5460 Inv and Wms in The Cloud - 1540851493083001pfjmPRANAYPRASOONNo ratings yet

- Modul Amuk P1 SoalanDocument34 pagesModul Amuk P1 SoalanSukHarunNo ratings yet

- Magic Maths Triangle 4x4 PDFDocument2 pagesMagic Maths Triangle 4x4 PDFRaja Pathamuthu.GNo ratings yet

- Particle Swarm Optimization: Algorithm and Its Codes in MATLABDocument11 pagesParticle Swarm Optimization: Algorithm and Its Codes in MATLABSaurav NandaNo ratings yet

- Lecture Note of Chapter OneDocument30 pagesLecture Note of Chapter OneAwet100% (1)

- Supplier Performance ReviewDocument2 pagesSupplier Performance ReviewbasavarajhNo ratings yet

- Biology Project Report: Study of The Effect of Avenue Trees On Temperature Under Canopy and OutsideDocument12 pagesBiology Project Report: Study of The Effect of Avenue Trees On Temperature Under Canopy and Outsidephilip50% (2)

- Hannah Arendt On Power ArticleDocument9 pagesHannah Arendt On Power ArticleIsabela PopaNo ratings yet

- 2.4 Million For Productivity Improvement of MachinesDocument1 page2.4 Million For Productivity Improvement of MachinesAnkit VyasNo ratings yet

- Altera JTAG-to-Avalon-MM Tutorial: D. W. Hawkins (Dwh@ovro - Caltech.edu) March 14, 2012Document45 pagesAltera JTAG-to-Avalon-MM Tutorial: D. W. Hawkins (Dwh@ovro - Caltech.edu) March 14, 2012imanNo ratings yet

- Create Cost Center Element GroupDocument4 pagesCreate Cost Center Element GroupRock SylvNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument8 pagesJurnalNafik MunaNo ratings yet

- Pag-Iimahen Sa Batang Katutubo Sa Ilang PDFDocument28 pagesPag-Iimahen Sa Batang Katutubo Sa Ilang PDFLui BrionesNo ratings yet