Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University

Uploaded by

narciso netoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sage Publications, Inc. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University

Uploaded by

narciso netoCopyright:

Available Formats

Top-Management-Team Tenure and Organizational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of

Managerial Discretion

Author(s): Sydney Finkelstein and Donald C. Hambrick

Source: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 3 (Sep., 1990), pp. 484-503

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell

University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2393314 .

Accessed: 24/08/2013 04:47

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University are collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Administrative Science Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Top-Management-Team Drawing on an upper-echelons framework to study the ef-

Tenure and Organiza- fects of top-management-team tenure and modeling

managerial discretion as a moderating variable, this study

tional Outcomes: The examined the relationship between managerial tenure

ModeratingRole of and such organizational outcomes as strategic persistence

ManagerialDiscretion and conformity in strategy and performance with other

firms in an industry. In a sample of 100 organizations in

Sydney Finkelstein the computer, chemical, and natural-gas distribution in-

Universityof Southern dustries, executive-team tenure was found to have a sig-

California nificant effect on strategy and performance, with

long-tenured managerial teams following more persistent

Donald C. Hambrick strategies, strategies that conformed to central ten-

ColumbiaUniversity dencies of the industry, and exhibiting performance that

closely adhered to industry averages. Consistent with the

theory, results differed depending on the level of mana-

gerial discretion, with the strongest results occurring in

contexts that allowed managers high discretion.'

Recently, scholars in strategic management have emphasized

the role of executive leadership in strategy formation and or-

ganization performance. While a concern for the role of top

management is not new (Barnard, 1938), the recent perspec-

tive goes beyond earlier prescriptions for effective manage-

ment. In particular,this new approach emphasizes the

importance of understanding the background, experiences,

and values of top managers in explaining the choices they

make. While a number of researchers may be identified with

this stream of research (Kotter, 1982; Gupta and Govindar-

ajan, 1984; Szilagyi and Schweiger, 1984; Kets de Vries and

Miller, 1986), the work of Hambrick and Mason (1984) is par-

ticularly germane to the study presented here. They argued

that both strategic choices and organization performance are

associated with the characteristics of the top managers in a

firm. This "upper-echelons theory" is based on the premise

that top managers structure decision situations to fit their

view of the world. As a result, a central requirement for un-

derstanding organizational behavior is to identify those factors

that direct or orient executive attention.

As intuitively appealing as the upper-echelons perspective

might be, it does not receive consistently strong support

when tested. Moreover, it is at odds with another conclusion

espoused by some theorists: that top managers have rela-

tively little influence on organizational outcomes because of

environmental and inertial forces (Lieberson and O'Connor,

1972; Hannan and Freeman, 1977; Salancik and Pfeffer,

1977).

?

In an attempt to reconcile these competing views, recent

1990 by Cornell University. theorists have taken a contingency approach. In some cases,

0001 '8392/90/3503-0484/$1 .00.

environments determine organizational forms and fates; in

other cases, managers, through their choices, have a great

This project was supported by the Social role in affecting outcomes (Hrebiniakand Joyce, 1985). As a

Sciences and Humanities Research

Council of Canada, the Irwin Foundation, theoretical bridge between these extremes, Hambrick and

and Columbia University's Executive Finkelstein (1987) developed the concept of managerial dis-

Leadership Research Center. We would

like to thank Warren Boeker, Bert Can-

cretion to refer to the latitude of action available to top exec-

nella, Ming-Jer Chen, John Delaney, Jim utives. Discretion is a means of accounting for differing levels

Fredrickson, Sara Keck, Nandini Rajago- of constraint facing different top-management groups. Where

palan, Mike Tushman, and the anonymous

reviewers for their helpful comments on discretion is low, the role of the top-management team is

earlier drafts of this paper. limited, and upper-echelons theory will have weak explana-

484/AdministrativeScience Quarterly,35 (1990): 484- 503

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

tory power. Where discretionis high, managers can signifi-

cantly shape the organization,and managerialcharacteristics

will be reflected in organizationaloutcomes.

To test both upper-echelonstheory and the moderatingrole

of managerialdiscretion,we conducted two majortests. The

first is an examinationof the relationshipbetween managerial

tenure and such organizationalcharacteristicsas strategic

persistence and conformityto industryaverages, a straight-

forwardupper-echelonstest. Althoughseveral studies have

investigatedtenure (e.g., Pfeffer, 1983), none has fullydevel-

oped and exploredthe propositionthat long tenures are asso-

ciated with strategic inertiaand close adherence to industry

averages.

The second inquiryis whether the strength of the association

between managerialtenure and organizationalpersistence/

conformitydepends on the degree of managerialdiscretion

present. To test this, we sampled high-,medium-,and low-

discretionindustries,distinguishingbetween high-and low-

discretionorganizationswithin each industry.

THEORYAND HYPOTHESES

The Upper-Echelons Argument

The upper-echelonsperspective, as set forthby Hambrickand

Mason (1984), attributesmajorinfluenceto a firm's leaders.

Organizationaloutcomes, such as strategies and perfor-

mance, are expected to reflect the characteristicsof these

leaders. The logic of this view relies on earlywork by

theorists of the CarnegieSchool, who arguedthat complex

decisions are largelythe result of behavioralfactors rather

than perfectlyrationalanalysis based on complete information

(Marchand Simon, 1958; Cyertand March,1963). Intheir

view, bounded rationality,multipleand conflictinggoals, ill-

defined options, and varyingaspirationlevels-and, in turn,

actions or inactions-are all derivedfrom beliefs, knowledge,

assumptions, and values that decision makers bringto the

administrativesetting.

This behavioralview of decision makingis especially relevant

for top managers,who face great complexityand ambiguityin

their tasks. Managersare typicallyconfrontedwith numerous

bits of informationthat demand attention (Mintzberg,1973).

They must decide on appropriateresponses to "important"

stimuliand discardinformationthat is less important(Weick,

1979). What and how they respond, and how they define

what is "important,"depends on their interpretationof the

situation.And this interpretationprocess is simplifiedby ap-

plyinggeneral rules that a managercan relyon (Ranson,

Hinings,and Greenwood, 1980). Hence, cognitivelylimited

managersview a complex world and formulateunder-

standings that simplifypotentialresponse sets (Marchand

Simon, 1958:139). As a result, "choice is always exercised

with respect to a limited,approximate,simplified'model' of

the real situation."

Some supportfor the upper-echelonsperspective is available

in research using psychometricindicatorsof executive pre-

dispositions. Hage and Dewar (1973), who studied values,

found that executives' attitudes toward innovationwere as-

sociated with subsequent levels of organizationalinnovation.

485/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Gupta and Govindarajan (1984) found that general managers'

tolerance for ambiguity was more positively related to organi-

zational effectiveness of business units under conditions of

growth than under conditions of decline. Miller and Droge

(1986) found that chief executives' need for achievement was

strongly associated with organizational centralization, formal-

ization, and integration.

In a related but distinct vein, some researchers have demon-

strated associations between demographic characteristics of

managers and their behaviors or organizational outcomes.

Dearborn and Simon (1958) established this stream of re-

search by finding that managers' functional backgrounds

were related to their interpretation of critical problems in a

complex business case, although Walsh's (1988) more recent

work suggests that managerial belief structures may be more

complex than Dearborn and Simon's findings imply. Gupta

and Govindarajan (1984) found that the marketing and sales

experience of division managers was more strongly asso-

ciated with effectiveness of units pursuing growth strategies

than those pursuing harvest strategies. Kimberlyand Evan-

isko (1981) (studying hospitals) and Bantel and Jackson (1989)

(studying banks) both found that executive educational levels

were associated with organizational innovation.

An important feature of Hambrick and Mason's upper-ech-

elons perspective, which we adopt here, is a primaryfocus on

the top-management team rather than strictly on the chief

executive. Except in the most extreme cases, management is

a shared effort in which a dominant coalition (Cyert and

March, 1963) collectively shapes organizational outcomes.

The limited empirical evidence on whether the top person or

the broader team is a better predictor of organizational out-

comes consistently supports the conclusion that the full team

has greater effect (Hage and Dewar, 1973; Tushman, Virany,

and Romanelli, 1985; Finkelstein, 1988; Bantel and Jackson,

1989).

Effects of Top-Management-Team Tenure

There is no single characteristic of top teams that has been

studied sufficiently to understand its complete effects on or-

ganizational outcomes. However, the organizational tenure of

team members may qualify as having the most significant

theoretical footing of all demographic variables (Pfeffer,

1983). We draw from available literature to argue that a top

team's tenure in the organization affects (and serves as an

approximation for) the team's commitment to the status quo,

its informational diversity, and its attitudes toward risk. In

turn, team tenure is expected to affect organizational out-

comes. Specifically, firms led by long-tenured executives will

tend to have (1) persistent, unchanging strategies, (2) strate-

gies that conform closely to industry averages, and (3) perfor-

mance that conforms to industry averages.

As individuals spend time in an organization, and particularly

as they succeed and climb the organization's hierarchy, they

become convinced of the wisdom of the organization's ways

(Wanous, 1980). They become committed to their own prior

actions, especially when those actions were taken publicly

and were explicit,as typicallycharacterizesstrategic choices

486/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

(Salancik, 1977). Staw (1976) and his associates (Staw and

Fox, 1977; Fox and Staw, 1979; Staw and Ross, 1987) have

found experimentally that once people are committed to a

course of action, they resist changing their behavior, even

when the chosen course is not a successful one. Katz (1982)

also argued that tenure is associated with increased rigidity

and commitment to established policies and practices. In ad-

dition, long-term processes of socialization and filtering re-

duce the variance in the population of promotion candidates

in a firm, further enhancing continuity over time (March and

March, 1977).

Related to the effects tenure has on commitment to the

status quo are those it has on risk taking. At one level, com-

mitment derives from certain "psychological risks" of change

(Salancik, 1977). However, more tangible risks are also asso-

ciated with tenure, particularlyfor senior executives. Such in-

dividuals may have struggled for years to achieve their top

spots; their competencies have been deemed important for

the firm's current configuration; as long-term employees,

they have more firm-specific than general human capital; and

they typically are well established in their communities, social

circles, and family life-cycles (Vancil, 1987). Essentially, they

have far more to lose than to gain by taking "unnecessary

risks" (Coffee, 1988).

Finally, tenure tends to restrict information processing. Over

time, organization members develop habits, establish "cus-

tomary" information sources, and rely more and more on past

experience instead of on new stimuli (Katz, 1982). With orga-

nizational tenure, managers tend to develop a particularrep-

ertoire of responses to environmental and organizational

stimuli that acts against any change in policy (Miller, 1988),

enhancing behavioral stability (Katz, 1982). The top team as a

whole tends to develop similar repertoires because long-term

acculturation of team members creates a common perspec-

tive or organizational paradigm (Pfeffer, 1983).

These social and psychological effects of tenure suggest cer-

tain organizational outcomes. Adopting a top-management

team level of analysis, the most obvious, but so far relatively

unstudied implication is that strategic persistence, defined as

the extent to which a firm's strategy remains stable over

time, increases with team tenures.1 Several scholars have

made related arguments, typically in the context of executive

succession (Chandler, 1962; Miller and Friesen, 1980;

Pfeffer, 1983; Tushman and Romanelli, 1985). For example,

Miller and Friesen (1980) have argued that long-serving CEOs

often show politically and emotionally motivated resistance

to change. However, aside from the well-documented ten-

dency for CEOs or teams freshly arrived from the outside to

make major strategic changes (e.g., Helmich and Brown,

1972; Tushman, Virany, and Romanelli, 1985), we know of

only limited evidence that strategic persistence is related to

managerial tenures (Grimm and Smith, 1986).

I

This definition of strategic persistence is

A second effect of long tenures is to reduce the adoption of

in line with earlier discussions of similar novel or unique strategies (Katz, 1982), thus bringing the or-

constructs, such as strategic predisposi- ganization into general conformity with industry tendencies.

tion (Miles and Cameron, 1982) and per-

sistence in questionable strategies Such strategic conformity, defined as the extent to which a

(Schwenk and Tang, 1987). firm's strategy conforms to the centraltendency of the entire

487/ASO, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

industry, increases with team tenures. Teams with short

tenures have fresh, diverse information and are willing to take

risks, often departing widely from industry conventions. As

tenure increases, perceptions become very restricted and risk

taking is avoided. The lowest-risk thing to do is to follow the

general tendency of mainstream competitors. Thus, even

though we expect change to diminish as tenures increase,

we expect whatever strategic change does occur to bring the

firm into closer conformity with industry averages. Long-

tenured teams make few strategic changes, and those few

are merely imitative, reflecting impoverished information pro-

cessing and risk aversion.

The third effect of top-team tenures is an extension of the

second. Namely, just as tenure increases conformity to in-

dustry strategic averages, so does it also increase conformity

to industry performance averages. Performance conformity is

defined as the extent to which a firm's performance is sim-

ilar to the average for the industry. Short-tenured managers

who undertake deviant strategies may experience very high

or very low performance within the industry. Longer-tenured

teams who pursue mainline strategies will experience perfor-

mance close to industry averages.

Alternatively, although we argue that managerial tenures have

very clear effects on organizational outcomes, firm strategy

and performance may influence the distribution of tenures at

the top as well. For example, firms following persistent strat-

egies may make few changes in top-team composition, in-

creasing tenures. Although we develop theory and adopt

methods that attempt to reduce causal ambiguity, it remains

problematic. The hypotheses we have generated from the

above discussion do not explicitly consider reverse causality

in modeling the effects of top-managerial tenure on organiza-

tional characteristics:

Hypothesis la: Top-management-teamtenure is positivelyasso-

ciated with strategic persistence.

Hypothesis lb: Top-management-teamtenure is positivelyasso-

ciated with strategic conformity.

Hypothesis lc: Top-management-teamtenure is positivelyasso-

ciated with performanceconformity.

Moderating Role of Managerial Discretion

Upper-echelons theory emphasizes the role of top managers

in affecting organizational outcomes. However, it is well

known that executives do not always have complete latitude

of action (Lieberson and O'Connor, 1972; Hannan and

Freeman, 1977). Under conditions of restricted discretion,

managerial predispositions become less important and envi-

ronmental and organizational factors become more significant

in influencing strategy and performance (Hambrickand Fin-

kelstein, 1987). Because top managers of some organizations

have more discretion than their counterparts in other organi-

zations, managerial characteristics will not always be predic-

tive of organizational outcomes. Hence, in this study, we

would expect managerial tenure to affect strategic persis-

tence, strategic conformity, and performance conformity

more in high-discretion than in low-discretion situations.

488/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

Hambrick and Finkelstein (1987) argued that discretion is de-

termined by three sets of forces: (1) the degree to which the

environment allows variety and change; (2) the degree to

which the organization is amenable to an array of possible ac-

tions and empowers the executive to formulate and execute

those actions; and (3) the degree to which the executive per-

sonally is able to envision or create multiple courses of ac-

tion. This study limits its focus to environmental and

organizational sources of discretion.

Environmental influences on organizations and managers

have been well documented in the industrial organization

(Scherer, 1970) and organization theory (Thompson, 1967) lit-

eratures. Organizations function within domains defined by

their products or services and by the markets they serve (Le-

vine and White, 1961). The characteristics of these domains,

particularlythe industry the firm competes in, greatly affect

the level of managerial discretion. For example, Lieberson and

O'Connor (1972) found that more variance in profitability

could be attributed to CEOs in industries with high advertising

intensity and high growth rates-both of which signal discre-

tion (Hambrickand Finkelstein, 1987)-than in more com-

modity-like or low-growth industries.

Industries may differ along several important dimensions that

affect the level of managerial discretion. One such dimension

is product differentiability. Industries characterized by product

differentiability offer managers discretionary domains that are

not available in commodity goods industries. For example,

manufacturers of apparel, computers, and toys have latitude

about price, product form, styling, packaging, distribution, and

promotion (to name but a few), which would not exist in such

commodity industries as natural-gas distribution and coal

mining. It is in these high-discretion industries that top man-

agers can have their greatest impact on organizational out-

comes.

Other sources of environmental discretion are demand insta-

bility, low capital intensity, competitive market structures,

market growth, and freedom from government regulation. In-

dustries that are characterized by these factors offer greater

discretion to top managers than do other, more constrained

industries.

The organization itself may also have characteristics that in-

hibit or enhance top-managerial discretion. Two of the most

important are inertial forces and resource availability(Ham-

brick and Finkelstein, 1987). Organizational inertia occupies an

important place in theories of organizational adaptation

(Hannan and Freeman, 1977; Aldrich, 1979; Miller and

Friesen, 1980; Hannan and Freeman, 1984; Tushman and

Romanelli, 1985). Inertia tends to reduce managerial flexibility

in managing critical domains. Large organizations, in partic-

ular, have great difficulty changing (Aldrich, 1979), inhibiting

managerial discretion. For example, Miller and Toulouse

(1986) found that CEO personality was more strongly related

to structure in small firms than in large firms.

Resource availability is a second important influence on man-

agerial discretion. Since virtuallyall strategic initiatives require

adequate resources for implementation, deficiencies may re-

duce managers' range of options. This importantrole for slack

489/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

has been emphasized by numerous researchers (Cyertand

March,1963; Pfeffer and Salancik,1978; Bourgeois, 1981;

Miles and Cameron,1982; Singh, 1986). Managerialdiscre-

tion is enhanced by the availabilityof slack resources.

Hypotheses based on an upper-echelonstheory of organiza-

tions need to consider limitsto strategic choice. The concept

of managerialdiscretion,by identifyingthe conditionsthat en-

hance and inhibitmanagerialaction, presents a framework

for doing so. We have identifiedsources of discretionat both

the industryand firmlevel that will affect the relationshipbe-

tween team tenures and organizationaloutcomes:

Hypothesis 2a: Top-management-teamtenure is more stronglyre-

lated to strategies and performance(as discussed above) in high-

discretionindustriesthan in low-discretionindustries.

Hypothesis 2b: Top-management-teamtenure is more stronglyre-

lated to strategies and performance(as discussed above) in high-

discretionorganizations(withinan industry)than in low-discretion

organizations.

METHOD

Sample

Industrieswere selected to represent low-, moderate-,and

high-discretionenvironments.FollowingHambrickand Finkel-

stein (1987), the followingcharacteristicswere used as the

primaryindicatorsof environmentaldiscretion:productdiffer-

entiability,growth, demand instability,low capitalintensity,

and low degree of regulation.Applyingthese criteriato each

of 16 industrieslisted in the 1982 Forbes and Business Week

surveys, we selected the computer,chemical,and natural-gas

distributionindustriesas the high-,medium-,and low-discre-

tion environments,respectively,to be examined.

The computer industry,characterizedby continuous product

innovation,productdifferentiation,and high growth rates,

was selected as the high-discretionindustry.The chemical in-

dustryexhibitedmoderate discretion,constrainedby its de-

pendence on energy as feedstocks and its cyclicality.Sources

of discretionincludedinternationalcompetition,significant

productdevelopment, and the need to manage demand in-

stability.The natural-gasdistributionindustrywas selected as

the low-discretionindustry.Supplyand demand were greatly

constrainedby factors such as the economic climate, interna-

tionaloil prices, and government regulation,which controlled

decisions from pricingto capitalacquisition.

A sample of 100 firms, including35 computer,35 chemical,

and 30 natural-gasdistributioncompanies, was drawnfrom a

populationof the largest firms in each industryfor which data

were availableon strategies and top managersfor all fiscal

years between 1978 and 1982. With pooling(discussed

below), there are 500 observations (100 firms for 5 years).

The sample was restrictedto large firms because data on top

managers of smallerfirms are often inaccessible, and a rela-

tively homogeneous set of firms were requiredto ensure

comparability.Because of these choices, however, our re-

sults may have limitedgeneralizability.

All corporateofficers who were also boardmembers were in-

cluded in our definitionof the top-managementteam. The re-

sulting managerialset is representativeof the dominant

490/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

coalition (Cyert and March, 1963) at the apex of an organiza-

tion. Although other individuals may influence organizational

outcomes, board membership was chosen as the criterion

because it is an objective, and formal, indicator of member-

ship in the inner circle of managers (Thompson, 1967; Mace,

1971). The average size of the top-management team, as de-

fined, was 3.5, with a standard deviation of 2.

Data on strategic attributes, organizational performance, and

managerial discretion were obtained from Compustat,

Moody's Industrial Manual, and Moody's Utilities Manual.

Data on top-managerial tenure were obtained from Dun &

Bradstreet Reference Book of Corporate Management.

Measures

Strategic persistence. This variable measures the extent to

which a firm's strategy remains fixed over time. Conceiving of

strategy as a pattern in a stream of important decisions

(Mintzberg, 1978), we used six strategic indicators to create

composite measures of persistence: (1) advertising intensity

(advertising/sales), (2) research and development intensity

(R&D/sales), (3) plant and equipment newness (net P&E/gross

P&E), (4) nonproduction overhead (SGA expenses/sales), (5)

inventory levels (inventories/sales), and (6) financial leverage

(debt/equity). These dimensions were chosen because (a)

they are potentially controllable by top managers; (b) they

may have an important effect on firm performance; (c) they

are complementary, each focusing on an important but spe-

cific aspect of the firm's strategic profile; and (d) they are

amenable to data collection and have relatively reliable com-

parabilityacross firms within an industry. All have been used

in previous strategy research; advertising intensity, R&D in-

tensity, and plant and equipment newness are basic resource

allocations, the SGA to sales ratio addresses a firm's ex-

pense structure, the inventory to sales ratio measures pro-

duction cycle time and working capital management, and the

debt to equity ratio is an accepted measure of financial le-

verage (Schoeffler, Buzzell, and Heany, 1974; Schendel and

Patton, 1978).

The composite persistence measures were calculated as

follows: Treating t as the focal year, the firm's five-year (for

t - 1 through t + 3) variance (E t, - 7)2/n - 1) for each

strategic dimension was computed.2 Next, variance scores

for each dimension were standardized by industry, using data

points from sample firms only (mean = 0, standard deviation

= 1), and multiplied by minus one to bring the measures in

line with the concept of persistence (i.e., absence of strategic

variance over time).

Finally, the six standardized indicators were summed to yield

an overall measure, Strategic Persistence 1 (SP1). Because

two of the indicators-advertising and R&D intensity-had

considerable missing data, particularlyfor the natural-gas dis-

2 tribution industry, an alternative measure, Strategic Persis-

We used this time period because we tence 2 (SP2), was also developed based only on the other

were interested in capturing changes from four indicators (items 3 through 6, above). The missing data

just before the focal year, as well as after.

Hence, this approach captures change by reduced the N for SP1 to 155.

top teams that break with the past. Re-

sults did not change when strategic per- The rationale for creating these composite measures (and

sistence was measured from t to t + 4. those that follow, for strategic and performanceconformity)

491/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rests on two premises. First, the summary measures can be

considered strategic decision patterns. In keeping with the

logic of the constructs, strategic persistence (and conformity)

represent patterns in an array of actions (Mintzberg, 1978).

The most appropriate way to assess such strategic decision

patterns is to examine actions on multiple fronts. As a result,

the summary measures of persistence and conformity more

closely reflect the dependent variables of our theoretical

model than do the individual indicators of strategy. The

second reason for adopting this perspective is that it allows

more parsimonious analysis than examination of various

items singly would afford.

Strategic conformity. This variable measures the degree to

which a firm's strategy matches the average strategic profile

of its competitors in the same industry. The strategic dimen-

sions making up the composite measures are the same as

those used in the strategic persistence measure. The major

difference in the two operationalizations is that, while stra-

tegic persistence examines variabilityover time, strategic

conformity assesses strategy at one point in time (year t). The

approach was as follows: For year t, each strategic dimension

was standardized by industry, using data points from sample

firms only (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1). Next, the ab-

solute difference between a firm's score on a strategic di-

mension and the average score for all sample firms in that

industry was calculated. These absolute differences were

then multiplied by minus one to convert their meaning to

"conformity" (i.e., absence of differences from competitors).

Strategic Conformity 1 (SC1) was created by summing all six

indicators, and Strategic Conformity 2 (SC2) by summing

items 3 through 6. Missing data reduced the N for SC1 to 155.

Performance conformity. This variable is analogous to stra-

tegic conformity but assesses the extent to which a firm's

performance aligns with the average of its competitors in the

same industry. Because of the weaknesses inherent in any

one measure of performance (Venkatraman and Ramanujam,

1986), three indicators were used: return on equity, return on

assets, and market value/book value of owner's equity. Once

again, items were standardized by industry, and absolute dif-

ferences were calculated, multiplied by minus one, and

summed to yield an overall measure of Performance Con-

formity (PC).

Because each of the individualcomponents of the persis-

tence and conformity measures represents only one part of a

wider construct, and are supplementary, not alternative mea-

sures for each other, and because these indicators are not

distributed normally, intercorrelations among variables are not

meaningful as reliabilityindicators. Nevertheless, Cronbach

alphas for the five summary measures ranged from .41 to .69,

reasonable given these caveats.3

Tenure. This was measured as the mean number of years of

employment in the firm of top-management-team members

in year t. Several alternative measures of managerial tenure

were considered, including tenure in position, tenure in the

3

top-management team, and tenure in the industry. Tenure in

The actual alphas were as follows: SP1:

.57; SP2: .63; SC1: .41; SC2: .49; and the firm was adopted here because it was the tenure variable

PC: .69. most highly correlated with other tenure measures, hence

492/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

serving as a central,parsimoniousindicatorof the broadcon-

cept of tenure. Further,the other tenure measures yielded

patternsthat were generallyvery similarto those reportedfor

tenure in the company. Inaddition,age was examined as an

alternativeexplanatoryvariableto tenure. Althoughboth were

highlycorrelated(r = .56), tenure was much more predictive

than age in several regressions, suggesting that the associa-

tion between tenure and the dependent variableswas not

due to an age effect.

Size. One of the organizationalfactors affecting managerial

discretionwas size, calculatedas the numberof employees in

the firm in year t (inthousands). Firmswith many employees

face bureaucraticmomentum (Mintzberg,1978) and often

have severe difficultieseffecting change (Aldrich,1979). Al-

ternativemeasures of size, such as sales and assets, were

highlycorrelatedwith the numberof employees; results re-

mainedthe same for all three measures.

Immediateslack. A second factor affecting managerial'discre-

tion is slack resources. Ourmeasure attempted to capture

the degree of immediate resource availability.The annual

workingcapitalratio(workingcapital/sales),adopted here, as-

sesses the cushion a firm has to meet needs and opportuni-

ties on a short-termbasis (Bourgeois,1981; Singh, 1986). The

conventionalmeasure of longer-termslack, equity/debt,was

not used because its reciprocalwas includedin the computa-

tion of the dependent variableindices.

Performance.A potentialconfoundingdeterminantof stra-

tegic persistence is performance.Therefore,the five-year

average returnon equity was includedas a controlvariablein

analyses of strategic persistence.

To ensure comparabilityacross industries,all independent

variableswere standardizedby subtractingindustrymeans

and dividingby industrystandarddeviations, using data from

sample firms only.

Data Analysis

The data includeboth cross-sectionaland time-series compo-

nents. Such data can be exploited by poolingthe cross sec-

tions together for availableyears, producingstatistics that

indicatethe average effect of the independentvariablesover

the full period. Because largersamples are possible, more

precise estimates can be obtained. However, poolingcross-

sectional data presents two problems. First,slope coeffi-

cients may varyover time, renderingpooled techniques

inappropriate(Maddala,1977). And second, ordinaryleast

squares (OLS)estimates may be biased because of enduring

individual-firmcharacteristicsthat are not considered in the

model, violatingassumptions on independence of observa-

tions (Hannanand Young, 1977).

The problemof model instabilityover time was assessed

using a proceduresuggested by Maddala(1977: 322-326).

F-valuesrangedfrom .33 to 1.08, all of which were insignifi-

cant, indicatingthat slope coefficients did not varyover time.

Hence, the data were pooled.

Because of potentialbias in OLScoefficients, we primarily

used modifiedgeneralizedleast squares (GLS)models to

493/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

control explicitly for nonindependence of observations

(Hannan and Young, 1977). Because they specifically control

for firm-specific variabilityin cross-sectional time-series data,

GLS models do not produce the biased estimates that OLS

models might. This allows the time-series component of the

data to be exploited, maximizing degrees of freedom. Ex-

amples of this approach can be found in recent work by

Brown (1982), Masters and Delaney (1985), and Stearns,

Hoffman, and Heide (1987).

Two sets of GLS regressions were conducted. First, we re-

gressed outcomes on tenure (along with the control variables)

for the full sample to test for main effects. Second, we did

similar regressions for each industry to test the moderating

role of environmental discretion.

To test the moderating role of organizational discretion, and to

assess more rigorously the incremental effect of adding man-

agerial discretion as a moderator, we also report R2s and R2

increments in OLS regressions. In particular,three sets of

OLS regressions were performed. The first reported R2s for

the main effect. The second and third tested for the incre-

mental effect of managerial discretion, by adding interactions

for tenure and industry (two dummy variables) and the inter-

actions for tenure and size and slack, consecutively. By

limiting our use of OLS strictly to an examination of R2 incre-

ments, we avoid the problematic biases of specific coeffi-

cients.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and correlations

among the variables. Although significance levels are noted,

they should be interpreted with caution because the data

have been pooled. There are several patterns worth noting.

First, with an average team tenure of about 22 years, our

sample seems to be weighted toward long-tenured top

teams. However, the standard deviation of tenure was about

12 years, providing significant variabilityfor statistical tests.

Second, team tenure was positively correlated with both stra-

tegic persistence measures and all three conformity mea-

sures, often with substantial magnitude. This preliminary

result is consistent with our hypotheses linking tenure to out-

comes.

Table 1

Pearson CorrelationCoefficients of All Variables in Study*

Variable Mean S.D. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1. SPi 0 3.8

2. SP2 0 2.6 .93-

3. SC1 -4.6 1.6 .23- .21-

4. SC2 -3.1 1.3 .20- .14- .85-

5. PC -1.7 1.5 .35- .23- .19- .21--

6. Tenure 21.6 11.7 .47- .34- .21- .30- .12-

7. Performance 26.0 12.0 .04 - .01 - .13 - .10- .02 - .12-

8. Size 19.1 40.3 .32- .12- .30- .05 .11- .19- .03

9. Slack 22.0 18.7 -.19- -.25-- .01 -.15- -.14- -.19- .16- -.01

*lp < .05; *-p < .01.

* N = 500, except for SP1 and SC1, where N = 155.

494/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

Table2

Results of GLS Regressions on Team Tenure in Firm*

SPi SP2 SC1 SC2 PC

Variable (N = 155) (N = 500) (N = 155) (N = 500) (N = 500)

Tenure(X1) .92w .500 .06 .20- .15-

(.38) (.16) (.15) (.07) (.09)

Size (X2) 1.04 .19 .47 .15 .12

(.67) (.18) (.24) (.11) (.13)

Slack (X3) -.33 -.51 .06 .00 -.09

(.50) (.17) (.15) (.07) (.11)

Performance (X4) .14 .05 - - -

(.23) (.13)

*p < .10; Up < .05; "p < .01.

* Unstandardizedregressioncoefficients; standarderrorsare in parentheses. Y = a + b1X1 + b2X2 + b3X3 + b4X4

+ U.

Third, both size and slack were correlated with strategic per-

sistence, positively for size and negatively for slack. This sug-

gests that firms with persistent strategies were larger and

had less slack than other firms. Size was also positively asso-

ciated with SC1 and PC. Given these correlations, size and

slack were included as controls in regressions on tenure.

Table 2 presents regression results for the full sample. Using

generalized least squares, we regressed each of the five de-

pendent variables on tenure, size, and slack. As noted above,

the five-year average return on equity (performance) was also

included as a control variable for strategic persistence.

Strong support was found for a relationship between team

tenure and measures of persistence and conformity. Four of

five regression coefficients were significant and in the hy-

pothesized direction.4 The association between team tenure

and strategic persistance was especially strong. Firms led by

long-tenured top-management teams were significantly more

likely to follow persistent strategies.5 One of two regression

coefficients for strategic conformity was also significant at p

< .01. Finally, tenure and performance conformity were mar-

ginally related (p < .10) in the hypothesized positive direction.

The control variables, size, slack, and performance, yielded

mixed results. Of note, however, is the positive association

between size and all five dependent variables, with the coef-

ficient in the SC1 model significant. While only marginal, this

4

result does seem to suggest that larger firms tended to make

Followinga suggestion of an ASQ re-

fewer strategic changes. Coefficients for slack were more

viewer,we tested the robustnessof these mixed, although slack and SP2 were negatively and signifi-

resultsfor firmsof varyingages. Thatis, cantly associated. Performance was positively, but not signifi-

high-performing olderfirmsmay see no

reasonto change a successful strategy.If cantly related to the dependent variables.

these firms have long-tenuredtop man-

agers as well, similarpatternsof persis- Table 3 reports regression results for each of the three indus-

tence and conformitymay result. tries. The computer industry represents the high-discretion

However,the inclusionof this age effect environment, where we expected the strongest associations

in regressionswas not significantand did

not change the results. between tenure and organizational outcomes. Conversely,

5

managerial discretion is much more constrained in the nat-

Alternatively,it is possible to arguethat

ural-gas distribution industry, and we expected team tenure

teams with low variancein tenures form to have a weak association with the outcome measures. Fi-

a cohortwhose memberstend to act very nally, the moderate levels of discretion prevalent in the

similarly,amplifyingstrategicpersistence,

but this hypothesiswas not supportedin chemical industry should result in tenure effects somewhere

our sample. between those in the other two industries.

495/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Table3

Results of GLS Regressions on Team Tenure by Industry*

Computer Industry

SPi SP2 SC1 SC2 PC

Variable (N = 95) (N = 175) (N = 95) (N = 175) (N = 175)

Tenure(X1) 1.59- 1.110 .14 .23 .45w

(.62) (.40) (.23) (.12) (.18)

Size (X2) 1.67 .37 .45 .04 .31

(.94) (.30) (.53) (.17) (.22)

Slack (X3) .00 .06 .32 .26w .32*

(.62) (.50) (.17) (.11) (.18)

Performance (X4) .11 .06 - - -

(.28) (.23)

Chemical Industry

SPi SP2 SC1 SC2 PC

(N= 60) (N= 175) (N= 60) (N= 175) (N= 175)

Tenure(X1) .33 .18 .01 .04 -.35

(.41) (.10) (.17) (.09) (.19)

Size (X2) .36 .12 .56 .38 .34

(.59) (.17) (.32) (.17) (.22)

Slack(X3) -.20 .07 -.52 -.18 -.21

(.77) (.16) (.27) (.12) (.20)

Performance (X4) -.12 .08

(.32) (.09)

Natural-GasDistributionIndustry(N = 150)

SPi SP2 SC1 SC2 PC

Tenure(X1) - -.06 - .39w .34

(.13) (.17) (.21)

Size (X2) - -.34 - .05 -.17

(1.01) (.24) (.24)

Slack (X3) - -.09 - -.10 -.30

(.45) (.12) (.18)

Performance (X4) - .17 -

(.24)

*p < .10; "p < .05; "p < .01.

* Unstandardizedregression-poefficients;standarderrorsare in parentheses. Y = a + b1X1 + b2X2 + b3X3 + b4X4

+ U.

Results generally support these predictions. Tenure coeffi-

cients in the computer industry were significant in the hy-

pothesized direction in four of five cases. Tenure coefficients

in the chemical industry were significant in the hypothesized

direction only once, as was the case in the natural-gas in-

dustry. Computer-industry coefficients were significantly

greater than those in the chemical industry in all regressions

except SC1 (p < .01 for PC; p < .05 for SP1 and SP2; p < .10

for SC2; by Arnold's, 1982, "split groups" test). In addition,

coefficients in the computer industry were greater than those

in the natural-gas industry in two of three cases, significantly

for SP2 (p < .01). Hence, the relationship between top-team

tenure and firm persistence and conformity was strongest in

the high-discretion computer industry.

Estimates for the control variables indicate some interesting

patterns. In both the chemical and natural-gas industries,

slack was typically negative and in two of eight cases, signifi-

cant. In contrast, slack was positive and significant (in three

496/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

of five cases) in the high-discretion computer industry. This

suggests a possible complementary effect, such that organi-

zational sources of discretion, like slack, become important

when environments confer limited latitude, while in higher-

discretion contexts they may actually constrain choice. As ex-

pected, size was positively associated with the dependent

variables, and significant in three of 13 cases.

An effective way to summarize the role of managerial discre-

tion is to examine its incremental effect in consecutive re-

gressions on tenure. Table 4 reports R2s of three regressions

for each dependent variable: (1) on tenure (and the control

variables), (2) on tenure (and the control variables) and the in-

teraction of tenure and two industry dummy variables, and (3)

on tenure (and the controls), industry x tenure interactions,

and the interactions of tenure with both size and slack.

These results confirm those reported above for GLS models.

Environmental and organizational sources of discretion im-

proved explained variance significantly in all five models, pro-

viding strong support for hypotheses 2a and 2b. Regressions

run on subsamples of high and low size and slack firms sub-

stantiated these results. Tenure coefficients were significant

in the hypothesized direction in four out of five cases for both

low-size and high-slack groups, while significant results were

found in only one of five regressions in the high-size and low-

slack subsamples.

The results thus indicate considerable support for the hypoth-

eses. In general, the longer a top team's tenure, (a) the more

persistent, or unchanging, the firm's strategy, (b) the more

the firm's strategy conformed to central tendencies of the in-

dustry, and (c) the more the firm's performance aligned with

industry averages. However, the strength of these patterns

differed depending on how much discretion the setting con-

ferred on top managers. For example, the association be-

tween team tenure and organizational outcomes was

substantially stronger in the high-discretion computer industry

than in the lower-discretion chemical and natural-gas distribu-

tion industries. Similarly, team tenure and organizational out-

comes bore a stronger correspondence in small and

high-slack firms-those with substantial managerial discre-

tion-than in large and low-slack firms.

Table4

Results of OLS Regressions on Team Tenure in Firm*

SPi SP2 SC1 SC2 PC

(N = 155) (N = 500) (N = 155) (N = 500) (N = 500)

Model I R2 .30 .25 .16 .11 .03

Model IIR2 .33 .31 .19 .12 .06

Ffor IIvs. 1 7.700 19.370 5.26- 3.57- 6.200

Model IllR2 .38 .33 .22 .14 .09

Ffor IIIvs. ll 5.61- 6.26- 2.95- 1.99- 3.64-

*p < .10; "p < .05; "p < .01.

*Model l: Y= a + b1X1 + b2X2 + b3X3 + b4X4 + b5X5 + b6X6 + u; ModelIl: Y= a + b1X1 + b2X2 + b3X3 +

b4X4 + b5X5 + b6X6 + b7X1X5 + b8X1X6 + u; Model IlIl:Y = a + b1X1 + b2X2 + b3X3 + b4X4 + b5X5 +

b6X6 + b7X1X5 + b8X1X6 + b9X1X2 + b10X1X3 + u; where X1 = tenure, X2 = size, X3 = slack, X4 =

performance;X5 = 1 if computerindustry,= 0 if other industry;X6 = 1 if chemicalindustry,= 0 if other industry;

and u = error term,

497/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

DISCUSSION

Effects of Team Tenure

As a straightforwardupper-echelonstest, this papersheds

new lighton the possible effects that top-team tenures may

have on the strategies and performanceof organizations.Our

results revealthe organizationaloutcomes of escalating com-

mitment, riskaversion,and restrictionsin informationpro-

cessing that develop as top-managerialtenure increases.

Namely, long-tenureteams do not engage in as much stra-

tegic experimentationand change as short-tenureteams.

Long-tenureteams tend to pursue imitativestrategies directly

in line with industrytrends, whereas short-tenureteams tend

to pursue novel strategies that deviate widely from industry

patterns.Correspondingly,organizationswith long-tenure

teams exhibitorganizationalperformancethat closely adheres

to industryaverages, while short-tenureteams are associated

with performancelevels that deviate-being either much

higheror lower-from industrytendencies.

These findings, particularlyfor persistence, are consistent

with priorfindingsthat outside successors tend to undertake

substantialstrategic change (e.g., Helmichand Brown, 1972).

Infact, one could ask whether our results are due strictlyto

extreme behaviorsby brand-new,short-tenureteams. We

exploredthis possibilityby examiningthe data by grouped

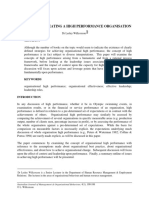

gradationsof team tenures. As Figure1 (a,b,c)illustrates,the

results strikinglyindicatethat the organizationalattributes

varysystematicallyacross the fullspectrum of tenure lengths.

A new interpretationcan thus be placed on the conclusions of

priorresearchers regardingoutsiders. Namely,what is most

importanttheoreticallyabout outsiders is not that they are

outsiders but that they have very short tenures. Outsidersare

simply at an extreme on a continuum;they are not qualita-

tively special cases. As theirtenures increase, almost with

each passing year, they graduallytend to make fewer stra-

tegic changes, to imitateor match strategictendencies of the

industry,and, accordingly,to be associated with firm perfor-

mance that rises and falls in line with industryfortunes. Top-

team tenure appears to be a construct of fundamentaland

widespread importanceto organizations.

Discretion as a Moderator

We went beyond the basic upper-echelonsmodel (Hambrick

and Mason, 1984) by examiningmanagerialdiscretionas a

potentiallyimportantmoderatorof the association between

executive characteristicsand organizationaloutcomes. Re-

sults were strengthened, at times substantially,when mana-

gerial discretionwas accounted for. Explainedvariancewas

significantlyincreased in all ten regressions by addingeither

industryor organizationalindicatorsof discretion.Majordif-

ferences were found across differentlevels of both environ-

mental and organizationaldiscretion.The characteristicsof

top-managementteams were most stronglyreflected in or-

ganizationaloutcomes in the computer industry,which pro-

vided significantlatitudeof action. Conversely,the natural-gas

distributionindustrywas more restrictive-a commodity-like

product,capitalintensive, mature,highlyregulated-and ex-

ecutive-team tenure was typicallyunrelatedto strategic per-

sistence and conformity.This findingsuggests that choice of

498/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

Figure 1. Graphs of organizational outcomes at different gradations of

team tenure.*

a. +2

*0

0~~~~~~~~~~

C

0~ ~~~~~~~~ 0

0-

in ~ ~ ~ TemTnr (nYas

in -2

0~

0~~~

%6.(

U) -

0

0-5 5-10 10-15 15-20 20-25 25-30 30-35 35-40

Team Tenure(in Years)

L0 )

%6-)

c.

X I_ I l l

E

-2-

c; 0

mace-1friylrengtv

E(1

scoes ndcatlss onormty

499/ASQ,~

Setmer19

0-5 5-10 10-15 15-20 20-25 25-30 30-35 35-40

Team Tenure(in Years)

*ForStrategicConformityand Perfor-

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

industry in tests of upper-echelons theory is a critical decision

that requires careful consideration. Moreover, it implies that

top-managerial staffing decisions may have very different

consequences depending on industry. In high-discretion con-

texts, as in the computer industry, managers seem to matter

greatly. In contrast, top teams in low-discretion contexts,

such as in the natural-gas distribution industry, may have

much less bearing on organizational outcomes.

Managerial discretion was also assessed at the organizational

level of analysis. Again, results supported the hypotheses.

When the organization allowed significant latitude to top

managers, as evidenced by abundant slack or small size, the

firm's degree of strategic persistence and conformity typically

reflected the tenure of the top team. Conversely, in more re-

strictive organizations-those that were large or had little

slack-managerial profiles showed little association with or-

ganizational outcomes.

The importance of organizational discretion in explaining stra-

tegic decision patterns suggests that it does have a role to

play in upper-echelons theory. Some organizations afford their

top managers more opportunity for impact than others. As

found here, and as argued by Hambrick and Finkelstein

(1987), organization size and slack seem to be among the

critical determinants of discretion.

Limitations

Several important limitations of the study warrant discussion.

First, we restricted our focus to top managers when, in fact,

lower-level employees may be influential in professional firms

or in those with emergent strategies. However, the highest

managers and the CEO retain considerable symbolic influence

that can convey their preferences for lower-level initiatives

(Hage and Dewar, 1973; Pfeffer, 1981). Additionally, agenda

setting at the top serves as an important guide for lower-level

managers to follow (Kotter, 1982). While influence may ema-

nate from numerous parts of the organization, in this study

we have at least expanded our scope beyond the predomi-

nant focus on the CEO alone.

Second, our sample was restricted to large firms, and our

findings therefore may not be generalizable to all firms in an

industry. Managerial effects may be more intense in smaller

firms because they are less constrained by organizational in-

ertia (Miller, Kets de Vries, and Toulouse, 1982).

Another important limitation of the study concerns causality.

While hypotheses were stated in associational terms, the

logic behind them implies that managerial tenure "causes"

organizational outcomes. Unfortunately, even with longitu-

dinal data it was not possible to completely disentangle

causal direction. While the temporal ordering of team tenure

and the strategic persistence measures was consistent with

theory, hypotheses on conformity were tested at one point in

time. Accordingly, it seems plausible that both managerial

tenures and persistence and conformity are mutually rein-

forcing, a view very much in line with Miles and Snow (1978).

Long-tenured teams follow stable strategies, and firms that

follow stable strategies do not make many changes in execu-

tive leadership.

500/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

A fourth limitation concerns our measures of managerial dis-

cretion. While we used industry to represent environmental

sources of discretion, the construct may require more subtle

operationalization. For example, industries may not be consis-

tently high or low on every dimension that makes up environ-

mental discretion (Hambrickand Finkelstein, 1987).

Nevertheless, industry has been considered an adequate

measure of environment by many other researchers (e.g.,

Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967; Hrebiniakand Snow, 1980;

Porter, 1980), and the industries studied in this paper do differ

substantially across several key indicators of environmental

discretion. In a related vein, this paper did not address indi-

vidual sources of discretion.

Finally, to study environmental sources of discretion more ef-

fectively, a greater number of industries will be needed.

While important patterns emerged in our examination of three

widely disparate industries, our industry sample size was only

three, leaving considerable opportunity for other researchers.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results allow conclusions at two levels. First, it appears

that managerial team tenure has a profound influence on or-

ganizational outcomes, such as strategic persistence, stra-

tegic conformity, and performance conformity. The apparent

effect of tenure occurs over its full range of values and is not

just an artifact of the radical changes brought on by top man-

agers newly arrived from the outside.

At a second level, our results indicate that upper-echelons

theory should be extended to include a moderating role for

managerial discretion. As Pfeffer and Salancik (1978: 245)

have argued, "it is necessary to develop a model that sug-

gests how much constraint an administrator faces in formu-

lating action." This paper illustrates that such a position has

strong empirical support, at least in the context of managerial

tenure.

There is clearly opportunity for further research to investigate

both managerial discretion and upper-echelons theory. The

results reported here addressed managerial tenure; other im-

portant demographic characteristics such as age, functional

background, industry experience, and education may yield

significant findings as well. This paper also suggests that a

more careful examination of the strategic choice paradigm is

required. Such research will greatly improve our under-

standing of the role of executive leadership in organizations.

REFERENCES

Aldrich, Howard Bantel, Karen,and Susan Jackson Bourgeois, L.J.

1979 Organizationsand Environ- 1989 "Topmanagementand inno- 1981 "Onthe measurementof or-

ments. EnglewoodCliffs,NJ: vations in banking:Does the ganizationalslack."Academy

Prentice-Hall. compositionof the top team of ManagementReview, 6:

Arnold, Hugh J. make a difference?"Strategic 29-39.

1982 "Moderatorvariables:A clas- ManagementJournal,10: Brown, M. Craig

sificationof conceptual,ana- 107-124. 1982 "Administrative succession

lytic,and psychometric Barnard,Chester and organizationperformance:

issues." OrganizationalBe- 1938 Functionsof the Executive. The succession effect." Ad-

haviorand HumanPerfor- Cambridge,MA: HarvardUni- ministrativeScience Quarterly,

mance, 29: 143-174. versity Press. 27: 1-16.

501/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chandler, Alfred D. Hambrick, Donald C., and Phyllis Kotter,John P.

1962 Strategy and Structure. Cam- Mason 1982 The GeneralManagers.New

bridge, MA: M.I.T. Press. 1984 "Upper echelons: The organi- York:Free Press.

Coffee, John C. zation as a reflection of its top Lawrence, Paul R., and Jay W.

1988 "Shareholders versus man- managers." Academy of Man- Lorsch

agers: The strain in the corpo- agement Review, 9: 193-206. 1967 Organization and Environment.

rate web." In John C. Coffee, Hannan, Michael T., and John H. Homewood, IL:Irwin.

Louis Lowenstein, and Susan Freeman Levine, Sol, and Paul E. White

Rose-Ackerman (eds.), Knights, 1977 "The population ecology of or- 1961 "Exchangeas a conceptual

Raiders, and Targets: 77-134. ganizations." American Journal frameworkfor the study of in-

New York: Oxford University of Sociology, 82: 929-964. terorganizationalrelationships."

Press. 1984 "Structural inertia and organi- AdministrativeScience Quar-

Cyert, Richard M., and James G. zational change." American terly, 5: 583-601.

March Sociological Review, 49:

149-164. Lieberson, Stanley, and James F.

1963 A Behavioral Theory of the O'Connor

Firm. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Hannan, Michael T., and Alice A. 1972 "Leadershipand organizational

Prentice-Hall. Young performance:A study of large

Dearborn, D. C., and Herbert A. 1977 "Estimation in multi-wave corporations."AmericanSo-

Simon panel models: Results on ciologicalReview, 37:

1958 "Selective perceptions: A note pooling cross-section and time 117-130.

on the departmental identifica- series." In D. Heise (ed.), So-

ciological Methodology: Mace, M. L.

tion of executives." Soci- 1971 Directors:Mythand Reality.

ometry, 21: 140-144. 52-83. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass. Boston: HarvardUniversity

Finkelstein, Sydney GraduateSchool of Business

1988 "Managerial orientations and Helmich, Donald, and W. Brown Administration.

organizational outcomes: The 1972 "Successor type and organiza-

tional change in the corporate Maddala, G. S.

moderating roles of managerial 1977 Econometrics.New York:

discretion and power." Unpub- enterprise." Administrative

Science Quarterly, 17: McGraw-Hill.

lished Ph.D. dissertation, Co-

lumbia University. 371 -381. March,James C., and James G.

Hrebiniak, Lawrence G., and March

Fox, Frederick V., and Barry M. 1977 "Almostrandomcareers:The

Staw William F. Joyce

1985 "Organizational adaptation: Wisconsinschool superintend-

1979 "The trapped administrator:

Strategic choice and environ- ency, 1940-1972." Adminis-

Effects of job insecurity and trativeScience Quarterly,22:

mental determinism." Admin-

policy resistance upon com- 377-409.

mitment to a course of ac- istrative Science Quarterly, 30:

tion." Administrative Science 336-349. March,James G., and HerbertA.

Quarterly, 24: 449-471. Hrebiniak, Lawrence G., and Simon

Charles G. Snow 1958 Organizations.New York:

Grimm, Curtis M., and Ken G. Wiley.

Smith 1980 "Strategy, distinctive compe-

1986 "The organization as a reflec- tence, and organizational per- Masters, MarickF., and John

tion of its top managers: An formance." Administrative Thomas Delaney

empirical test." Paper pre- Science Quarterly, 25: 1985 "Thecauses of unionpolitical

sented at the annual meeting 307-335. involvement:A longitudinal

of the Academy of Manage- Katz, Ralph analysis."Journalof LaborRe-

ment, Chicago. 1982 "The effects of group longevity search, 6: 341-362.

Gupta, Anil K., and V. on project communication and Miles, Robert H., and Kim S.

Govindarajan performance." Administrative Cameron

1984 "Business unit strategy, man- Science Quarterly, 27: 1982 CoffinNailsand Corporate

agerial characteristics, and 81 -104. Strategies. EnglewoodCliffs,

business unit effectiveness at Kets de Vries, Manfred F. R., and NJ: Prentice-Hall.

strategy implementation." Danny Miller Miles, Robert E., and Charles C.

Academy of Management 1986 "Personality, culture and orga- Snow

Journal, 27: 25-41. nization." Academy of Man- 1978 OrganizationStrategy,Struc-

Hage, Jerald, and Robert Dewar agement Review, 11: ture and Process. New York:

1973 "Elite values versus organiza- 266-279. McGraw-Hill.

tional structure in predicting Kimberly, John R., and Michael J. Miller,Danny

innovation." Administrative Evanisko 1988 "Stale in the saddle: CEO

Science Quarterly, 18: 1981 "Organizational innovation: tenure and adaptation."

279-290. The influence of individual, or- Workingpaper,McGillUniver-

Hambrick, Donald C., and Sydney ganizational, and contextual sity.

Finkelstein factors on hospital adoption of

technological and administra- Miller,Danny, and Cornelia Droge

1987 "Managerial discretion: A 1986 "Psychologicaland traditional

bridge between polar views on tive innovations." Academy of

Management Journal, 24: determinantsof structure."

organizations." In L. L. Cum- AdministrativeScience Quar-

mings and Barry M. Staw 689-713.

terly,31: 539-560.

(eds.), Research in Organiza-

tional Behavior, 9: 369-406.

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

502/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Managerial Discretion

Miller,Danny, and Peter H. Friesen Salancik, Gerald R., and Jeffrey Szilagyi, Andrew D., and David M.

1980 "Momentumand revolutionin Pfeffer Schweiger

organizational adaptation." 1977 "Constraintson administrator 1984 "Matching managers to strate-

Academyof Management discretion:The limitedinflu- gies: A review and suggested

Journal,23: 591-614. ence of mayorson city framework." Academy of

Miller,Danny, ManfredF. R. Kets budgets." UrbanAffairsQuar- Management Review, 9:

de Vries, and Jean-MarieToulouse terly, 12: 475-498. 626-637.

1982 "Topexecutive locus of control Schendel, Dan E., and G. Patton Thompson, James D.

and its relationshipto 1978 "A simultaneousequation 1967 Organizations in Action. New

strategy-making,structure,and model of corporatestrategy." York: McGraw-Hill.

environment."Academyof ManagementScience, 24: Tushman, Michael L., and Elaine

ManagementJournal,25: 1611-1621. Romanelli

237-253. Scherer, F. M. 1985 "Organization evolution: A

Miller,Danny, and Jean-Marie 1970 IndustrialMarketStructureand metamorphosis model of con-

Toulouse EconomicPerformance.Chi- vergence and reorientation."

1986 "Strategy,structure,CEOper- cago: RandMcNally. In L. L. Cummings and Barry

sonalityand performancein Schoeffler, Sydney, Robert Buzzell, M. Staw (eds.), Research in

smallfirms."AmericanJournal and D. Heany Organizational Behavior, 7:

of SmallBusiness, 10(3): 1974 "Theimpactof strategicplan- 171-222. Greenwich, CT: JAI

47-62. ningon profitperformance." Press.

Mintzberg,Henry HarvardBusiness Review, 52: Tushman, Michael L., Beverly

1973 The Natureof Managerial 137-145. Virany, and Elaine Romanelli

Work.New York:Harper& Schwenk, Charles, and Ming-Je 1985 "Executive succession,

Row. Tang strategy reorientation, and or-

1978 "Patternsin strategyforma- 1987 "Economicand psychological ganization evolution." Tech-

tion." ManagementScience, explanationsfor strategicper- nology in Society, 7: 297-314.

24: 934-949. sistence." Workingpaper, Vancil, Richard F.

Pfeffer,Jeffrey GraduateSchool of Business, 1987 Passing the Baton: Managing

1981 "Managementas symbolicac- IndianaUniversity. the Process of CEO Succes-

tion: The creationand mainte- Singh, Jitendra sion. Boston: HarvardBusi-

nance of organizational 1986 "Performance,slack, and risk ness School Press.

paradigms."In L. L. Cummings takingin organizationaldeci- Venkatraman, N., and Vasudevan

and BarryM. Staw (eds.), Re- sion making."Academyof Ramanujam

search in OrganizationalBe- ManagementJournal,29: 1986 "Measurement of performance

havior,3: 1-52. Greenwich, 562-585. in strategy research: A com-

CT:JAIPress. parison of approaches."

1983 "Organizational demography." Staw, BarryM.

Academy of Management Re-

In L. L. Cummingsand Barry 1976 "Knee-deepin the Big Muddy:

view, 11: 801-814.

M. Staw (eds.), Researchin A study of escalatingcommit-

Organizational Behavior,5: ment to a chosen course of Walsh, James P.

299-357. Greenwich,CT:JAI action."Organizational Be- 1988 "Selectivity and selective per-

Press. haviorand HumanPerfor- ception: An investigation of

mance, 16: 27-44. managers' belief structures

Pfeffer,Jeffrey, and Gerald R. and information processing."

Salancik Staw, BarryM., and FrederickV. Academy of Management

1978 The ExternalControlof Orga- Fox

Journal, 31: 873-896.

nizations:A Resource Depen- 1977 "Some determinantsof com-

dence Perspective.New York: mitmentto a previously Wanous, J. P.

Harper& Row. chosen course of action." 1980 Organizational Entry: Recruit-

HumanRelations,30: ment, Selection, and Socializa-

Porter, Michael E. 431 -450. tion of Newcomers. Reading,

1980 CompetitiveStrategy:Tech- MA: Addison-Wesley.

niques for AnalyzingIndustries Staw, BarryM., and Jerry Ross

and Competitors.Glencoe, IL: 1987 "Behaviorin escalatingsitua- Weick, Karl E.

Free Press. tions: Antecedents, proto- 1979 The Social Psychology of Or-

types, and solutions."In L. L. ganizing, 2d ed. Reading, MA:

Ranson, Stewart, Bob Hinings, and Cummingsand BarryM. Staw Addison-Wesley.

Royston Greenwood (eds.), Researchin Organiza-

1980 "Thestructuringof organiza- tionalBehavior,9: 39-78.

tionalstructures."Administra- Greenwich,CT:JAIPress.

tive Science Quarterly,25:

1-17. Stearns, Timothy M., Alan N.

Hoffman, and Jan B. Heide

Salancik, Gerald R. 1987 "Performanceof commercial

1977 "Commitmentand the control televisionstations as an out-

of organizational behaviorand come of interorganizational

belief." InBarryM. Staw and linkagesand environmental

GeraldR. Salancik(eds.), New conditions."Academyof Man-

Directionsin Organizational agement Journal,30: 71-90.

Behavior:1-54. Chicago:St.

ClairPress.

503/ASQ, September 1990

This content downloaded from 129.81.226.149 on Sat, 24 Aug 2013 04:47:11 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- R Lab - Probability DistributionsDocument10 pagesR Lab - Probability DistributionsPranay PandeyNo ratings yet

- Ceo Attributes and Firm Performance: A Sequential Mediation Process ModelDocument28 pagesCeo Attributes and Firm Performance: A Sequential Mediation Process ModelMehmood AliNo ratings yet

- Regression Analysis AssignmentDocument8 pagesRegression Analysis Assignmentضیاء گل مروت100% (1)

- Understandable Statistics Concepts and Methods 12th EditionDocument61 pagesUnderstandable Statistics Concepts and Methods 12th Editionherbert.porter697100% (36)

- Yukl LeadershipDocument16 pagesYukl LeadershipSandeep Hanuman100% (1)

- Volatility Based Envelopes VbeDocument6 pagesVolatility Based Envelopes Vbedanielhsc100% (1)

- Modelo Hambrick Mason 1984Document15 pagesModelo Hambrick Mason 1984ESTEFANIA SALAS CORNEJONo ratings yet

- Academy of ManagementDocument15 pagesAcademy of ManagementRevi ArfamainiNo ratings yet

- The Academy of Management Journal: This Content Downloaded From 149.200.255.110 On Sat, 06 Nov 2021 22:31:59 UTCDocument32 pagesThe Academy of Management Journal: This Content Downloaded From 149.200.255.110 On Sat, 06 Nov 2021 22:31:59 UTCinfoomall.psNo ratings yet

- Chatterjee 2007Document36 pagesChatterjee 2007Perminder SinghNo ratings yet

- Top Management Team Demography and Corporate ChangDocument33 pagesTop Management Team Demography and Corporate ChangabdulsamadNo ratings yet

- Upper EchelonsDocument15 pagesUpper EchelonsAminath Abdulla SaeedNo ratings yet

- Toward More Accurate Contextualization of The Ceo Effect On Firm PerformanceDocument19 pagesToward More Accurate Contextualization of The Ceo Effect On Firm PerformanceRevi ArfamainiNo ratings yet

- The Top Manager-Adviser Relationship in Strategic Decision Making During Executive Life Cycle: Exploring The Impediments To Strategic ChangeDocument14 pagesThe Top Manager-Adviser Relationship in Strategic Decision Making During Executive Life Cycle: Exploring The Impediments To Strategic ChangeAnonymous qAegy6GNo ratings yet

- Building Theoretical and Empirical Bridges Across Levels, Multilevel Research in ManagementDocument16 pagesBuilding Theoretical and Empirical Bridges Across Levels, Multilevel Research in ManagementZairaZaviyarNo ratings yet

- A Strategic Perspective on Compensation ManagementDocument49 pagesA Strategic Perspective on Compensation ManagementdjNo ratings yet

- Power in Top Management Teams Dimensions, Measurement, and ValidationDocument35 pagesPower in Top Management Teams Dimensions, Measurement, and ValidationFatih ÇetinNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data: Introduction To Special Topic ForumDocument13 pagesCorporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data: Introduction To Special Topic ForumVictor sanchez RuizNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management and Performance: International Journal of Management Reviews May 2003Document48 pagesHuman Resource Management and Performance: International Journal of Management Reviews May 2003Rakshita SolankiNo ratings yet