Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arts in Education: A Systematic Review of Competency Outcomes in Quasi-Experimental and Experimental Studies

Uploaded by

Cristine Mae MacailingOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arts in Education: A Systematic Review of Competency Outcomes in Quasi-Experimental and Experimental Studies

Uploaded by

Cristine Mae MacailingCopyright:

Available Formats

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

published: 15 April 2021

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623935

Arts in Education: A Systematic

Review of Competency Outcomes in

Quasi-Experimental and

Experimental Studies

Verena Schneider* and Anette Rohmann

Department of Community Psychology, FernUniversität in Hagen (University of Hagen), Hagen, Germany

Arts education in schools frequently experiences the pressure of being validated by

demonstrating quantitative impact on academic outcomes. The quantitative evidence

to date has been characterized by the application of largely correlational designs and

frequently applies a narrow focus on instrumental outcomes such as academically

relevant competencies. The present review aims to summarize quantitative evidence

from quasi-experimental and experimental studies with pre-test post-test designs on the

Edited by: effects of school-based arts education on a broader range of competency outcomes,

Corinne Jola, including intra- and interindividual competencies. A systematic literature search was

Abertay University, United Kingdom

conducted to identify relevant evaluation studies. Twenty-four articles reporting on 26

Reviewed by:

Pamela Burnard,

evaluation studies were eligible for inclusion, and their results were reviewed in terms of

University of Cambridge, art domains and outcome categories. Whilst there is some evidence of beneficial effects

United Kingdom

on some competencies, for example of music education on arithmetic abilities, speech

Roger Mantie,

University of Toronto segmentation and processing speed, the evidence across arts domains and for different

Scarborough, Canada outcomes is limited due to small sample sizes, small number of studies, and a large

*Correspondence: range of effect sizes. The review highlights that sufficiently powered (quasi-)experimental

Verena Schneider

verena.schneider@lcds.ac.uk

studies with pre-test post-test designs evaluating arts education are sparse and that

the “gold standard” of experimental research comes at the expense of a number of

Specialty section: other study characteristics such as sample size, intervention and follow-up length. By

This article was submitted to

Health Psychology,

summarizing the limitations of the current (quasi-)experimental research, the application

a section of the journal of experimental designs is critically assessed and a combination with qualitative methods

Frontiers in Psychology

in mixed-method designs and choice of relevant outcomes discussed.

Received: 30 October 2020

Accepted: 11 March 2021 Keywords: arts education, music, dance, drama, visual arts, systematic (literature) review, competencies

Published: 15 April 2021

Citation:

Schneider V and Rohmann A (2021)

INTRODUCTION

Arts in Education: A Systematic

Review of Competency Outcomes in Can the arts promote the creative skills needed for innovation? What are the beneficial effects

Quasi-Experimental and Experimental of music training on computation skills, spatial performance, memory and reading skills? Do

Studies. Front. Psychol. 12:623935. actors have better verbal and emotional skills? Can dance promote a sense of belonging? Does arts

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623935 education improve educational attainment, attention and motivation?

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 1 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

Questions about effects of arts education on outcomes such 2010). Second, arts can be taught as a stand-alone subject or be

as academic achievement and competencies have inspired much integrated into other subjects or the wider teaching approach.

research in an effort to defend the arts’ position in curricula. For example, arts integration has been found to be beneficial

Qualitative, mixed-method and quantitative research support the across art domains, ages and outcomes (e.g., Hardiman et al.,

notion that engagement in the arts can contribute to positive 2014; Lee et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2018). However, the term arts

outcomes such as academic achievement, attainment, social integration is often interchangeably used for different approaches

behavior and social transformation alongside health benefits such (Institute for Arts Integration and STEAM, 2019), varying from

as wellbeing (Deasy, 2002; Ewing, 2010; McLellan et al., 2012a, arts enrichment which uses the arts as a tool of engagement

2015; Winner et al., 2013; Fancourt and Finn, 2019). However, to using science, technology, engineering, the arts and math to

the so-called “gold standard” experimental research designs are guide students’ critical thinking (STEAM; Perignat and Katz-

rare, and findings on the causal impact on academically relevant Buonincontro, 2019). The distinction between different forms of

outcomes have frequently been limited or inconclusive (e.g., engagement and degree of integration appears important to take

Winner et al., 2013). Yet, experimental designs are often not account of the very different experiences and aims.

suitable for educational evaluation studies and their ability to Third, a distinction can be made by the consideration of

capture the complex experiences in arts learning have been intrinsic (e.g., express communal meaning, McCarthy et al.,

questioned (Ewing, 2010). Further, small sample sizes and short 2004) vs. instrumental outcomes (e.g., academic outcomes).

follow-up periods are common in experimental studies and McCarthy and colleagues note that the former is rarely

preclude confidence in conclusions. Finally, while the choice considered in the literature. In their review of arts and transfer

of instrumental outcomes such as children’s performances in into non-arts domains, Winner et al. (2013) critically discuss

other subjects may seem attractive, the implications of an the sole focus on instrumental outcomes as these promote an

exclusive focus on such outcomes have been critically discussed evaluation of the arts as a means to an end rather than for their

(Winner et al., 2013). The current review therefore seeks, own sake. The Reviewing Education and the Arts Project (REAP)

first, to summarize the evidence from quasi-experimental and (Hetland and Winner, 2001; Winner and Hetland, 2001) included

experimental studies on a range of transferrable skills and a series of meta-analyses to assess the relationship between

competency outcomes in school-based arts education. Second, it arts engagement and academic outcomes. The results indicated

seeks to describe and evaluate the methodological characteristics that, despite some positive correlations, the only significant

of the included studies and implications on conclusions. causal claims concerned the effects of music listening and music

According to Oxford University Press (2019), art is defined instruction on spatial reasoning (Hetland, 2000a,b) and of drama

as the “expression or application of human creative skill and on verbal skills (Podlozny, 2000). Music training may also

imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or positively affect math outcomes (Vaughn, 2000); however, there

sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their was a too-large range of effects in a small number of studies

beauty or emotional power” (1st paragraph), and the arts as the to draw definitive conclusions. The same was true for dance,

“various branches of creative activity, such as painting, music, with some evidence found for effects on visual-spatial skills, but

literature, and dance” (2nd paragraph). These definitions are again based on a small number of studies (Keinänen et al., 2000).

reflective of the arts as activities which involve creative problem Evidence for the effects of the arts on creativity transfer could

solving and opportunities for expression. Arts engagement can not be found (Moga et al., 2000). In 2013, a review published by

further involve social interaction and collaboration and allow the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

for an exploration of the self in an environment removed from (OECD) updated and extended the findings of REAP (Winner

the binary evaluation of performance as either right or wrong. et al., 2013) by including evaluations of behavioral and social

The arts may therefore be well positioned to stimulate the outcomes. Evidence from quasi-experimental and experimental

development of intra- and interpersonal outcomes. For example, studies indicated social and behavioral benefits of drama, such

as McLellan et al. (2012b) argue using the theoretical framework as empathy, emotion regulation, and perspective-taking. Effects

of the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985), the of music training were found on academic performance as well

arts may offer opportunities for experiences of competence, as intelligence, word decoding and phonological skills. There

autonomy and relatedness which in turn promote motivation were also indications of a beneficial effect of music on language

and wellbeing. learning, but limited support for an effect on visual-spatial

reasoning. Associations between drama or dance and creativity

State of Research were apparent but based on only a few studies with small

Research into the impacts of arts education can be categorized sample sizes, therefore limiting the ability to draw conclusions. A

by the type of arts experience or engagement. First, research further series of reviews of quantitative and qualitative evaluation

can be categorized whether it evaluates the effects of arts studies of arts in schools and the community by Jindal-Snape

appreciation or that of active arts participation. For example, et al. (2014a,b, 2018) found similarly varied results concerning

a long research tradition has examined the so-called Mozart academic outcomes, with a tendency for effects to be more

effect, in which Rauscher et al. (1993) observed that participants evident in music and multi-art contexts and more pronounced

showed significantly higher spatial performance after listening among pre-school children.

to a Mozart sonata. Although, replications and meta-analyses In general, the quantitative research to date provides mixed

have struggled to confirm these effects (e.g., Pietschnig et al., evidence regarding the effects of the arts on academic outcomes

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 2 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

and largely remains on the correlational level. However, there are given the more process focused, intrinsic experiences of the arts,

a few implications when interpreting these results. A difficulty one may expect stronger effects on the categories relating to

when comparing results from different studies and programs the inter- and intra-individual outcomes (i.e., “soft” skills) than

is a lack of a common evaluation approach and programs’ on transfer of learning to non-arts subjects (e.g., development

unique characteristics, contexts and quality (Ewing, 2010). of social bonds and empathy; McCarthy et al., 2004). While

Programs exhibit a substantial heterogeneity with respect to the DeSeCo categories were developed in consideration of

art domains, content, intensity, duration and delivery methods competencies which are instrumental to a successful life, they

of arts classes or interventions, all across a small number of may also contribute to the innate psychological needs for

studies. For example, failing to distinguish between different competence, relatedness and autonomy, which are the three key

forms of engagement with the arts (passive or active), how they needs proposed in the motivational self-determination theory

are integrated into the school curriculum and whether they (Deci and Ryan, 1985). The DeSeCo framework was thus

are offered in the form of a compulsory or extra-curricular chosen as a tool to group a wide range of outcomes into

activity adds many factors that may affect research results in categories and to enable an exploration of effects on similar and

different ways. dissimilar outcomes.

The current review aims to reduce some of the above

heterogeneity by synthesizing effects from quasi-experimental Research Questions

or experimental pre-test post-test designs on the impact of arts The current review seeks to systematically review competency-

education on a range of competencies. It seeks to evaluate based outcomes and effect sizes in (quasi-) experimental studies

programs which involve active involvement in the arts and of school-based arts education. Further, the review seeks to

teaching of the arts per se. Further, it aims to critically evaluate the critically assess the qualities of the included studies in respect to

strengths and limitations of the included studies. A wide range limitations of (quasi-) experimental research in arts education.

of outcomes will be included, and a framework of educational Research questions and exclusion and inclusion criteria are

outcomes, the OECD’s Definition and Selection of Competencies defined using the PICOS framework (participants, interventions,

(DeSeCo; Rychen and Salganik, 2003) will be used to group comparators, outcomes, and study design; Liberati et al., 2009).

outcomes into broader categories. Participants are defined as children or adolescents from the

general population attending formal compulsory education post

A Categorization of Outcomes pre-school. This review considers programs in which art is

We grouped outcomes into categories based on DeSeCo (Rychen taught as a stand-alone subject with a minimum session duration

and Salganik, 2003). The framework was the result of an of twenty minutes, as opposed to arts-integrated teaching

international, interdisciplinary and collaborative effort led by within or in combination with other subjects, focusing on

Switzerland and supported by the OECD. Key competencies were four art domains which are most frequently implemented in

identified in an extensive process bringing together empirical school curricula, namely the domains of music, drama, dance,

evidence, scholars and experts from different disciplines, and visual arts. Comparators include both active (treated)

including a final consolidation and revision phase. Providing a control groups participating in a non-arts or different arts

categorization of educational outcomes, the DeSeCo considers program as well as untreated control groups following the

individuals’ needs to lead a successful life and the needs of a standard curriculum. Studies reporting effect sizes on outcomes

functioning society. These competencies are summarized into relating to the DeSeCo framework (Rychen and Salganik, 2003)

three categories, namely using tools interactively, interacting in are included. The included study designs are natural/quasi-

socially heterogeneous groups, and acting autonomously. First, experimental, or experimental with pre-test post-test designs.

using tools interactively encompasses key competencies relating to Based on the above PICOS definitions, the review seeks to

using the tools of language and symbols, technology, information answer the following exploratory research questions: (1) How

and knowledge. Second, interacting in socially heterogeneous effective is arts education with respect to outcomes in the DeSeCo

groups refers to the social skills needed to work collaboratively categories (a) using tools interactively, (b) interacting in socially

in a diverse and multicultural society, to be able to control one’s heterogonous groups, (c) acting autonomously and d) the concept

emotions and to show empathy when relating to others and of reflectiveness? (2) What are the methodological characteristics,

dealing with conflict. Third, acting autonomously encompasses strengths and limitations of the included studies?

the key competencies needed for an individual to make

autonomous life choices and feel empowered to do so. Finally, an METHODS

underlying feature that applies to all categories of competencies

is reflectiveness, the ability to go beyond knowledge and The initial literature search was conducted in March 2019,

skills, to assimilate, change and adapt. Reflectiveness therefore following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews

encompasses meta-cognitive skills as well as the cognitive skills and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

essential for creative thinking. The databases PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Behavioral Science

Instrumental perspectives in evaluating arts education have Collection, PSYNDEX, Education Source and ERIC were

frequently focused on outcomes relating to the DeSeCo category searched with search strings combining terms related to art

using tools interactively (e.g., by assessing transfer effects to domains, intervention evaluation, and thesaurus explorations

non-arts subjects, linguistic or computational skills). However, of relevant outcome variables (Supplementary Table 1).

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 3 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

Bibliographies of relevant meta-analyses and systematic limited to statistical designs that did not include covariates or

literature reviews and further publications by authors with adjustments for violations of test assumptions. Effect sizes were

relevant studies were searched manually. The total number interpreted as small, medium and large according to Cohen’s

of search results was 1,807 from the databases and 13 from conventions (Cohen, 1988).

additional sources, leaving 1,681 search results after the removal

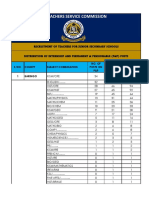

of duplicates (Figure 1).

The first author screened the articles’ titles, abstracts and

RESULTS

full texts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles The following narrative summary of included studies is

were included if they were research articles published in English structured into two sections. The first section summarizes effects

or German in peer-reviewed journals, were evaluation studies on outcomes relating to the DeSeCo categories using tools

of arts education for children and/or adolescents within the interactively, and the second section reports the outcomes on

school curriculum, with outcome variables relating to the above the “soft” skill outcomes in the categories interacting in socially

DeSeCo categories (Rychen and Salganik, 2003) and if they used heterogonous groups, acting autonomously and reflectiveness.

a quantitative or mixed methods approach with a natural/quasi-

experimental or experimental pre- and post-test design. Excluded

were studies reporting on extra-curricular programs (e.g., after-

Analysis of Studies With Outcomes

school clubs) or implemented in pre-schools, kindergarten, or Relating to the DeSeCo Categories Using

post-school contexts (e.g., universities), that were integrated as Tools Interactively

therapeutic interventions or addressed specific populations (e.g., Music Education

children with autism). Further, due to the risk of bias from Twelve studies assessing outcomes of music education relating

other confounding effects, studies reporting on programs in to the DeSeCo category using tools interactively fulfilled the

which the arts were just one intervention component out of inclusion criteria. Most used quasi-experimental designs, with

several (e.g., family counseling) were excluded. Finally, to take the exception of two studies with experimental designs (Rickard

account of the problematic interpretation of results based on et al., 2012, Study 2; Rabinowitch et al., 2013), and a

binary significance results (Siddaway et al., 2019), studies that treated control group was implemented in seven studies. Study

reported neither effect sizes nor sufficient statistics allowing characteristics were very heterogenous, with sample sizes varying

for the extraction and interpretation of effect sizes were also between n = 28 and n = 345, and program intensity and

excluded. After title and abstract screening, the full texts of the duration varying from weekly 20-min classes over an 8-week

54 remaining articles were screened, and 23 articles reporting period (Brodsky and Sulkin, 2011, Study 3) to 7 h per week over

a total of 25 studies were retained. The search was updated in several years (e.g., Degé et al., 2011; Supplementary Table 2).

April 2020 (Supplementary Table 1) and one additional relevant Two studies assessed arithmetic skills as an outcome of music

study was identified that had been published after the first education. A large effect size on arithmetic skills was extracted

search. Ten percent of articles during the title and abstract from one study of children receiving music composition classes

screening and another ten percent of articles during the full (Bugos and Jacobs, 2012), and a small effect size on computation

text screening were double-screened by a second independent scores was found among children taking piano lessons (Costa-

reviewer. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved Giomi, 1999). Processing speed was assessed in three studies,

through discussion, leading to full agreement on the inclusion revealing a medium effect of music composition training (Bugos

and exclusion of articles based on the pre-defined criteria. and Jacobs, 2012) and trivial (Guo et al., 2018) to small effects

Study characteristics relating to randomization, type of of instrumental music training (Roden et al., 2014b). Working

control group, sample size, participant age or grade, program memory was assessed in five studies, and whilst there was some

intensity and duration, main outcome measures, results and evidence for medium to large effects of music training on verbal

effect sizes were extracted for each study and are summarized or auditory components of working memory in three studies

in Supplementary Table 2. Further, theorized mechanisms of (Degé et al., 2011; Roden et al., 2012, 2014a), others had mixed

change in the included studies were recorded. While the study results, with trivial and small effect sizes or even contrary results

inclusion was based on effect size estimates, the precision of for the second year of intervention (Rickard et al., 2010; Guo

effect size estimates is dependent on the sample size. To address et al., 2018). In contrast to auditory functions, visual functions,

concerns about the accuracy of effect size estimates from small such as visual attention or memory, were generally not expected

samples, as well as a possible overestimation bias in eta-squared to be affected by musical education. The range of effect sizes,

(Morris, 2008; Fritz et al., 2012; Lakens and Evers, 2014), spanning from small with negative valence (Roden et al., 2014b)

additional confidence intervals and alternative effect sizes were to null or small effects with positive valence (Rickard et al., 2010;

calculated where possible (Lenhard and Lenhard, 2016; Uanhoro, Bugos and Jacobs, 2012; Roden et al., 2012) and medium positive

2017; Stangroom, 2019). Morris’ (2008) recommendation on the effect sizes Degé et al. (2011), may support the expected absence

use of effect sizes in pre-test post-test control group designs of effects of music education on visual functions. Furthermore,

was applied where possible. These additional calculations were the effects of music education on vocabulary and verbal learning

dependent on the availability of information in the papers variables ranged from small effect sizes with negative valence

regarding sample sizes, means and standard deviations of to small effect sizes with positive valence (Rickard et al., 2010;

pre- and post-test scores. Furthermore, these calculations were Bugos and Jacobs, 2012; Guo et al., 2018), with the exception of

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 4 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

FIGURE 1 | PRISMA flow diagram.

two medium-sized effects on language skills (Costa-Giomi, 1999) Teele Inventory for Multiple Intelligences (TIMI; adapted by

and verbal learning (Rickard et al., 2010). Brodsky and Sulkin Göǧebakan, 2003, as cited in Köksal Akyol, 2018) did not reach

(2011, Study 3) reported a large effect size on a composite score of significance. No effects were found on the mathematical-logical

dictation content and technical aspects of handwriting. No effects or visual-spatial subscales.

of music education on overall intelligence were found (Degé et al.,

2011). Comparisons Between Different Art Domains

Four evaluation studies included in this review compared the

Drama Education effects of an arts program to that of another arts program in

One experimental study with an untreated control group a different domain (Rickard et al., 2012; François et al., 2013;

evaluated the effect of a 2-hour long weekly drama class Hogenes et al., 2016). Two studies were experimental, and sample

with a total duration of 12 weeks on measures of intelligence sizes ranged from n = 24 to n = 133.

(Köksal Akyol, 2018). In the sample of 46 first grade children, Comparing the verbal learning and verbal intelligence over

a medium effect of the drama intervention on the verbal- time of students who received an increased frequency of music

linguistic intelligence subscale of the Turkish adaptation of the or drama lessons (Rickard et al., 2012, Study 1) revealed no

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 5 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

differences in verbal learning and delayed recall. However, a interventions ranged from weekly 30–60-min classes over a 3-

small effect size corresponding to greater improvement among month to a 3-year period.

music students was found for measures of immediate recall. Effect sizes regarding social skills and behavior were extracted

When comparing a group of music students to a painting group, from four studies (Rickard et al., 2012, study 2; Rabinowitch

music training affected speech segmentation processes with a et al., 2013; Schellenberg et al., 2015; Roden et al., 2016).

large effect size (François et al., 2013). Regarding non-verbal Whilst Roden and colleagues found that extended music training

intelligence, a large extracted effect size indicated that students buffered against increases in aggressive behavior observed in the

receiving increased music compared to increased drama classes control group, an effect of large size, the opposite trend was

exhibited greater improvement (Rickard et al., 2012, Study 1). observed for self-reported aggression in the study by Rickard and

Finally, Hogenes et al. (2016) compared the effects of a music colleagues. Rabinowitch and colleagues found that an interactive

composition to a music performance intervention. A medium musical intervention improved empathy in the music group

effect size for the between-group differences on post-test reading compared to the control group, an effect of medium size. For a

comprehension was due to a larger decrease among students subgroup with lower social skills at baseline, Schellenberg and

in the music performance group when controlling for pre- colleagues reported large effects of the group × time interaction

test scores. on sympathy and prosocial behavior due to significant increases

in the music group. Regarding intra-personal outcomes, two

Proposed Mechanisms of Change studies assessed effects of music education on self-esteem (Costa-

Several mechanisms to explain effects of the arts on non- Giomi, 1999; Rickard et al., 2012, Study 2), but neither study

arts outcomes were proposed by the authors of the included reported effect sizes. Costa-Giomi (1999) reported a significant

studies. For example, it was suggested that the simultaneous effect on self-esteem among children receiving piano lessons and

processing of multiple sensory cues required when playing computations revealed a small effect. However, Rickard et al.

music can explain working memory enhancement, specifically (2012) did not report significant group × time interactions when

enhancement of auditory components, including verbal memory comparing three groups of music, drama and control students

(e.g., componential model of working memory, Baddeley, 2010; over time.

Roden et al., 2014a). Others propose that improved attention and

mental processing speed due to music engagement may cause Drama Education

effects on academic performance (Roden et al., 2014b). Five studies assessed drama interventions’ effects on social

Other indirect pathways are proposed by applying competency outcomes (Walsh-Bowers, 1992; Walsh-Bowers and

motivational, social learning and evolutionary theories to the Basso, 1999; Rickard et al., 2012; Köksal Akyol, 2018). Four of

context of arts learning. Arts engagement may offer opportunities these applied a non-treated control group and two randomized

to experience flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975) and therefore group allocation with sample sizes varying from n = 44 to n =

improved attention and concentration (Bugos and Jacobs, 2012). 104. Program intensity and duration ranged from one 40-min to

Other pathways involving motivational learning processes have five 60-min classes per week over periods of 12–15 weeks.

been suggested with respect to collaborative learning in the arts Köksal Akyol (2018) reported no experimental effects on

(e.g., Vygotsky, 1977). An evolutionary perspective was applied intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence measures. In fact,

to the domain of childlore and handclapping songs (Brodsky and effect sizes calculated from the data provided in the article

Sulkin, 2011, Study 3). The latter was described as a naturally suggest a small effect on interpersonal intelligence in the opposite

occurring activity in 6–9-year-old children, with evidence of its direction as expected. Three studies conducted by Walsh-Bowers

existence dating back to 2000 BC. Combining sensory-motor, and colleagues (Walsh-Bowers, 1992; Walsh-Bowers and Basso,

social and verbal/linguistic elements, the study’s authors propose 1999) assessing social skill development in adolescents in a drama

an evolutionary developmental purpose predicted to affect program showed mixed results. There were generally no effects

development in non-arts domains such as motor and cognitive on self-rating scales of confidence in social situations, except for

development (Brodsky and Sulkin, 2011, Study 3). one small effect on self-rated cooperation (Walsh-Bowers and

Basso, 1999; Study 1). Intervention effects on teacher ratings

Analysis of Studies With Outcomes of social skills differed widely between studies, ranging from

Relating to the DeSeCo Categories medium and large effect sizes in support of the drama program to

large effects in the opposite direction, and intervention effects on

Interacting in Socially Heterogonous parents’ ratings of social skills ranged from small to large across

Groups, Acting Autonomously studies in support of the intervention. As with music students,

and Reflectiveness self-rated aggression scores among drama students seemed to

Music Education increase in comparison to a non-treatment control group over

Five evaluation studies of musical programs included in time (Rickard et al., 2012, Study 2). However, the group × time

this review addressed outcomes relating to the DeSeCo interaction was only marginally significant, and the effect was

categories interacting in socially heterogonous groups or acting only interpreted based on descriptive statistics of the three groups

autonomously. Two studies used an experimental design and at pre- and post-test.

three studies a treated control group, with sample sizes varying One experimental study with a treated control group assessed

between n = 24 and n = 84. The intensity and duration of non-verbal divergent thinking after a single drama improvisation

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 6 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

session in a sample of 34 ten- and eleven-year-old sixth grade external success attributions and worldviews were not significant

schoolchildren (Sowden et al., 2015a). Large intervention effect and effect sizes not retrievable. Self-reported creativity measures

sizes for the originality and elaboration measures from the were based on the dimensions of the Torrance Test of Creative

Incomplete Figures Tasks of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (Abedi, 2002). A large treatment effect was extracted

Thinking (Torrance, 1974, as cited in Sowden et al., 2015a) were for the creativity dimension of originality. No effect sizes could

found. The effect size for abstractness was non-significant and its be extracted for the non-significant effects on the creativity

size was not reported. dimensions of fluency, flexibility and elaboration.

Dance Education Comparisons Between Different Art Domains

Two studies evaluated the social outcomes of the weekly 90- One experimental (Freeman et al., 2003) and one quasi-

min dance intervention TanzZeit [time to dance], taught over experimental study (Rickard et al., 2012, Study 1) comparing

a period of one or two semesters in quasi-experimental designs the effects of music and drama interventions allowed for the

using untreated control groups (Zander et al., 2014; Kreutzmann extraction of relevant effect sizes on measures of self-image, self-

et al., 2018). The studies employed sizable samples (n = 606 and concepts, self-esteem, and attitudes. Sample sizes ranged from n

n = 361). = 111 to n = 185.

Both studies reported significant treatment effects on Freeman et al. (2003) reported no significant post-test

variables assessing affective and/or collaborative social networks, differences between music and drama groups. However, small

measured by asking students to indicate how much they liked effects according to Morris (2008) calculated on a subsample

or liked collaborating with each classmate, and their feelings with both pre- and post-measures indicate that drama students

of social belonging. Small effects of the dance intervention on exhibited greater improvement in self-reported self-image and

affective networks were found in one study (Kreutzmann et al., academic self-concept, and music students’ greater improvement

2018), but these were trivial in the study by Zander et al. (2014). in social self-concept. No differences were found in teacher

Kreutzmann and colleagues also reported evidence for affective ratings of social skills and problem behavior. Rickard et al. (2012)

social networks mediating the relationship between the dance did not report significant group × time interaction effects on

intervention and sense of social belonging. However, effect sizes the respective outcomes. However, small effect sizes according

for direct and indirect paths to social belonging remained on the to Morris (2008) indicate stronger effects of drama education

trivial level, and sensitivity analysis revealed that their sizes were on academic self-esteem, general attitudes and attitudes toward

dependent on the contrast codes employed. For collaborative social integration compared to the music group. Similarly, with

networks, Zander and colleagues reported small intervention medium effect sizes, drama had stronger effects on attitudes

effects in the subsample of boys, and large intervention effects for toward teaching and status among peers and medium to large

boys’ opposite-sex nominations. These effects were not observed effect sizes on engagement and motivation in arts class.

in the subsample of female participants.

One experimental study assessed the effects of a 20-min folk Proposed Mechanisms of Change

dance physical activity on creativity outcomes among Indian It has been proposed that music engagement may promote

children (Bollimbala et al., 2019). A sample of 34 sixth and empathic processes and social cohesion through the experience

seventh grade children were randomly assigned to a 20-min class of rhythmic and movement cohesion (Rabinowitch et al.,

or a sedentary control group. Pre- and post-tests of divergent 2013; Schellenberg et al., 2015), which can be explained from

and convergent thinking revealed small experimental effects on an evolutionary perspective (Huron, 2001; Tarr et al., 2014).

convergent thinking only, and a small effect in the opposite Similar mechanisms have been proposed for the effects of dance

direction was extracted on flexibility in divergent thinking across interventions on social outcome variables (Zander et al., 2014;

the entire sample. However, in the subgroup of children with Kreutzmann et al., 2018), with the additional aspect of physical

normal body mass index (BMI), as opposed to the other half proximity and opportunity for contact being a possible catalyst

of the sample with low BMI, small experimental effects were for friendships (theory of social impact, Latané et al., 1995).

revealed on all dimensions of the divergent and convergent According to Kreutzmann and colleagues, dance choreography

thinking measures. also creates an interdependency among participants which may

foster these social variables (social interdependence theory,

Visual Arts Education Johnson and Johnson, 2009). The drama intervention by Walsh

One evaluation study assessed the outcomes of two visual arts and colleagues (structured fantasy approach, Walsh et al., 1991)

programs on self-efficacy, self-concept, internal and external was derived from social development theory and the role of play

success attributions, worldviews and self-reported creativity for becoming competent in social situations (Vygotsky, 1967).

(Catterall and Peppler, 2007). A total of 179 nine to 10-year-old Similarly, Freeman et al. (2003) propose that elements of social

third grade children were assessed in a quasi-experimental design skills trainings are integral to creative drama and, like Catterall

with untreated control groups after 20–30 weeks of weekly 60- and Peppler (2007), propose that mastery experiences from the

to 90-min classes. Significant self-efficacy gains were observed creative classroom can transfer to generalized self-efficacy, as

among children in the visual arts groups, an effect of medium theorized in Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986).

size in relation to the changes in the control groups. Differences Catterall and Peppler, 2007 assessed creativity outcomes of

between groups and over time on self-concept, internal and visual arts programs and propose that visual arts programs

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 7 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

provide the learning environment to engage in metacognitive due to generally small sample sizes and unreliable effect size

activities, which are central in Bruner’s (1966) constructivist point estimates, as indicated by the large confidence intervals.

model, as well as active and collaborative learning (situated There was some evidence of the potential benefit of music

learning, Lave and Wenger, 1991; distributed learning, Bransford training on processing speed based on a few studies with small

and Schwartz, 1999). Sowden et al. (2015a) applied the dual- to medium effect sizes. However, no such effects were found in

process theory of creative thinking (Sowden et al., 2015b) to another study (Guo et al., 2018). Music students outperformed

identify the creativity processes, namely divergent thinking, they painting students with a large effect size difference in speech

expected to be specifically affected by an improvisation class. segmentation, as assessed by test performance and event-related

Four studies reported mixed method approaches by potentials (François et al., 2013). Inconsistent and trivial effects

incorporating observational and interview data (Walsh-Bowers, of music education were observed on vocabulary, visual memory,

1992; Walsh-Bowers and Basso, 1999; Catterall and Peppler, visual performance, and non-verbal intelligence. There was some

2007) to understand student’s responses to the intervention, their support for effects of music training on arithmetic abilities, but

engagement and processes of development. this was only based on a few studies and effect sizes ranged

from small to large. No effect of music training was found

Risk of Bias on global or verbal intelligence scores; however, a large effect

Several common risks of bias were identified across studies. Just emerged for non-verbal intelligence compared to a painting

over a quarter of the included studies (26.9%) fully randomized group. These mixed findings stand in contrast to previous

participants into groups, thereby minimizing systematic studies finding that music education increases intelligence. For

variation not caused by the experimental manipulation. Just over example, in an evaluation of a free community music program,

half of the studies (51.9%) included a treated control group. Such Schellenberg (2004) pre-assessed a sample of 6-year-old children

a comparison group is important to distinguish a treatment effect before entering first grade. At 1-year follow-up, small to medium-

from a behavior change merely due to the novelty or increased sized effects of music training on intelligence were found when

attention involved in participating in a new program, similar to compared to children with drama or no treatment. However,

a placebo effect (Winner et al., 2013). Less than a third of studies the effects of music education on cognitive outcomes may be

evaluated intervention durations of more than a year (30.8%), moderated by age. Developmental gains and plasticity in younger

while 15.4% of studies evaluated one-off classes or interventions children could explain differences by age in some cognitive effects

with a maximum 10 weeks duration. of arts education.

Only 7.4% of included studies recruited a sample size based Three studies assessed creativity outcomes of drama

on an a priori power analysis. Furthermore, 88.5% of studies improvisation, visual arts or dance classes. Large effects were

employed a sample size smaller than n = 200, which would be found for divergent thinking, mostly the originality dimension,

sample size required to detect a small time × group interaction after drama or visual arts classes. However, effects on divergent

effect in a 2 × 2 ANOVA (calculation in G∗ Power 3; Faul thinking were not as clear in an Indian sample of children

et al., 2007; f = 0.10, α = 0.05, 1–β = 0.80, correlation receiving a twenty-minute folk dance class, where the presence

among repeated measures = 0.5, non-sphericity correction = 1). of an effect seemed to be moderated by the children’s BMI

Insufficient statistical power has implications for the reliability (Bollimbala et al., 2019). It is important to note that two of these

of significance tests and effect size estimates. Information on studies assessed the children’s performance on creativity tests

participant attrition could be extracted from 12 studies, of which immediately after a single one-off class. Therefore, the effect may

one study had low attrition (below 5%), five studies medium (5– represent a momentary state of mind. On the other hand, longer-

20%) and six studies large attrition (more than 20%; attrition term effects of regular visual arts classes were only measured

classification according to Schulz and Grimes, 2002). Just over using a self-report creativity measure, and comparisons across

two-thirds of the studies provided reliability information for instruments should be made with caution (Catterall and Peppler,

the instruments used. Of these, half (nine studies) reported 2007). Based on the included studies, conclusions about the

acceptable reliability values (≥0.70) for all employed instruments. sustainability of creativity over time and differential effects of

longer-term versus one-off classes cannot be made.

DISCUSSION Regarding the outcome categories interacting in socially

heterogonous groups and acting autonomously, a small number

Answers to the Research Questions of studies were eligible for inclusion in this review. These

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in order examined a range of different outcomes with often inconclusive

to answer the following questions: (1) How effective is arts or even contrasting results. For interpersonal outcomes, positive

education with respect to outcomes in the DeSeCo categories (a) results with medium and large effects were reported for music

using tools interactively, (b) interacting in socially heterogonous training on the related concepts of empathy and sympathy as

groups, (c) acting autonomously and (d) the concept of well as prosocial behavior. However, these were based on only

reflectiveness? (2) What are the methodological characteristics a few studies. Furthermore, when looking at the effect of music

and limitations of the included studies? Regarding the outcome education on reducing unfavorable behavior, such as aggression,

category using tools interactively, most eligible studies reported the results were mixed across studies. Likewise, the evidence

on outcomes of music education. Wide ranges of effect sizes for effects of dance and drama on interpersonal outcomes was

were found across outcome variables. This variation may be uncertain due to a small number of studies and contrasting or

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 8 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

trivial effect sizes. Dance effects on some interpersonal outcomes year is required to determine if a transfer effect occurred (Moga

may be moderated by gender, an observation that calls for more et al., 2000). Only eight of the included studies met this criterion.

research applying moderation analyses. Finally, with respect to Results from short programs therefore need to be interpreted

intrapersonal outcomes, the suggested positive effects of music with caution.

on self-esteem and of visual arts on self-efficacy were based only Second, sample sizes tend to be smaller in (quasi-)

on single studies, which precludes a general conclusion. experimental designs. This results in small statistical power and,

The limited support for social-emotional outcomes of arts alongside short follow-up periods and variations in individual

education in this review contradicts a plausible expectation of experiences, non-significant cohort effects. A majority of the

such benefits, for instance due to the increased opportunities included studies had small sample sizes and would have been

for social interactions and collaboration which are characteristic insufficiently powered to discover small effects.

of performing arts. For example, previous research found some Third, arts programs are more difficult to standardize and

evidence for social and emotional benefits of drama on empathy, evaluation research needs to take the impact of the practitioner

perspective taking and emotional regulation, in line with such and participant relationship and adaptations in delivery into

expectations (Winner et al., 2013). A scoping review of the role account. According to Ewing (2010), stronger interventions are

of the arts for health and well-being published by the World the ones that can be adapted to the participants and contexts

Health Organization (Fancourt and Finn, 2019) delivered further which makes comparison across interventions more difficult.

evidence for beneficial effects of the arts on social cohesion Finally, outcomes need to be broad enough or appropriate for

among different populations in the community and particularly the respective program. As illustrated in the introduction, the

wide-ranging social-emotional benefits for socio-economically choice of exclusively instrumental outcomes has been critiqued

disadvantaged groups. However, the small number of included as it disregards the intrinsic outcomes of the arts. While the

studies and a number of limitations of these studies discussed DeSeCo framework selected for the categorization of outcomes

below call for caution to draw conclusions. Further, while this in this review adopts a wider perspective and arguably includes

review has focused solely on the class level, more subtle individual intrinsic processes in intra- and interpersonal level outcomes,

changes may be missed. The following discussion of the second the limitations of this perspective will be discussed below. In

research question will also debate the choice of outcomes and addition, qualitative research can be illuminating to understand

methods for their assessment. relevant outcomes and complex real-world experiences. As

The second aim of the review was to answer the question: proposed by Paluck (2010), field experiments do not need to be

What are the methodological characteristics, strengths and and should not be exclusively quantitative but can be integrated

limitations of the included studies? The review’s inclusion criteria with qualitative methods. The integration of qualitative data

focused on quasi- and experimental studies with pre-test post- allows to shed light on pathways and outcomes and can

test designs and effect size estimates. While quasi-experimental strengthen the conclusions from the quantitative data. For

studies are limited in their ability to provide causal evidence, example, in an evaluation of the impact of Creative Partnerships

experimental studies are commonly considered the “gold- (CP) on children’s wellbeing, the quantitative survey study with

standard” to demonstrate causal impact. Pre- and post-measures CP and control schools was complemented with qualitative case

allow for the control of changes over time and effect sizes and studies (McLellan et al., 2012b). While the former did not find

confidence intervals enable an estimation of the size and certainty statistically significant effects between the schools, the latter

of effects. However, the restrictive inclusion criteria resulted in illuminated mechanisms in high-wellbeing schools which can be

a small number of included studies, of which only 27% used fostered through arts integration and differences between the

randomization into intervention and control groups. The scarcity CP and control school (Galton and Page, 2014; McLellan and

of the so-called “gold standard” research method in the field may Steward, 2014). In another example in one of the here included

be partly due to practical considerations and financial limitations. studies, Catterall and Peppler (2007) conducted observations of

Further, it may be a reflection of a controversy between the need the visual arts and home classrooms in both intervention and

of rigorous evaluations, what scientific methods are appropriate control schools. The results of the observations complemented

for evaluations and the concern that experimental methods may their survey-based data by suggesting how the arts classes

be too reductionist to be suitable for more holistic and complex may have produced the observed effects. They observed higher

experiences and impacts of the arts. As discussed in the context of student engagement in arts classes, more positive relations

complementary medicine by Mason et al. (2002), these concerns between peers and with adults, a change in how teachers viewed

are not unreasonable and need to be acknowledged in the design students and significant improvements in the integration of two

of rigorous evaluation studies. case study students. Thus, the insights from the qualitative data

For example, programs evaluated in (quasi-) experimental can inform the design of future studies to test processes and help

designs tend to be shorter in duration and/or follow-up theory building.

compared to correlational research and may not provide long Hence, the integration of qualitative methods into field

enough exposure and follow-up to uncover meaningful effects experiments seems to be a promising approach. As the above

(Catterall, 2002; McCarthy et al., 2004). For example, this review examples illustrate, the combination of observation of classroom

also included studies which only evaluated one-off classes or very sessions and interviews of students and teachers within a field

short educational programs with short retest intervals. It has experiment enables a fuller elaboration of the mechanisms and

been suggested that a minimum intervention duration of one complexities in arts education. First, observations allow the

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 9 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

study of processes in the classroom, the in-depth analysis of characteristics (e.g., age group). Consequently, the heterogeneity

program characteristics and nuances in the delivery, engagement of the included studies with regard to these aspects limited the

and relationships in the classroom. Thus, the nature of conclusions that could be drawn across them. Additionally, the

experiences and specific ingredients of programs can be more criteria generated only a very small number of eligible studies

fully understood and compared. Second, interviews with students for most art domains except music. These were insufficient to

and teachers in intervention and control groups can help to answer the research questions in this review, highlighting the

understand the complex experiences in and outside the respective need for further experimental research with sufficient sample

classroom. For example, in an evaluation of the impact of sizes in the field, especially in the domains of drama, dance

a music orchestral program on collaborative skills, students and visual arts. Second, the limitation to studies in peer-

may be asked about how they like collaborative work and reviewed journals meant that the review excluded unpublished

to comment on experiences that created their like or dislike. literature. Risk of publication bias cannot be ruled out. Third,

Further, they could be asked questions about their collaborative while the exclusion of after-school clubs or programs outside

relationships with peers at school and to give examples of when of the school context attempted to minimize biases due to

they feel collaboration went well or not so well. Interviews accessibility and self-selection, not all included studies delivered

also enable a wider exploration of outcomes than what has programs within the mandatory curriculum and thus, some

been pre-specified in the quantitative data collection method. self-selection biases cannot be excluded. Fourth, the choice of

Therefore, rich data from qualitative research can help to support the DeSeCo framework and exclusion of studies in therapeutic

quantitative (experimental) research by illuminating important setting will have excluded intrinsic outcomes of arts education

program characteristics, experiences, pathways and outcomes not covered by the criteria. The results of this review should

which are difficult to uncover in exclusively quantitative group thus not be understood as a generalizable claim about the

level analysis. impact of the arts in general and rather be considered as an

As discussed above, there is a controversy about the overview and critical analysis of the limitations of the available

appropriateness of experimental designs in the evaluation of (quasi-)experimental research in terms of its outcomes and

the arts and holistic interventions. It may be fruitful to shift methodological characteristics.

the focus of the discussion away from the experimental design The current review focused on universal effects on the group

and toward the limitations of associated shortcomings, such as level, whilst the elaboration of moderators was not an objective.

the concern of being reductionist. Whilst a critical discussion However, it is important to note that some effects may be

of the “gold standard” is reasonable, the experimental design is stronger for different subgroups. For example, age has been

not incompatible with some of the solutions discussed above, shown to be related to intervention effect sizes, with greater

including qualitative research. effects for pre-school interventions compared to school-based

interventions (e.g., Campbell and Ramey, 1994; Ulubey, 2018).

Strengths and Limitations Similarly, other characteristics such as gender should be part

One of the key objectives of the current review was to provide of future moderator considerations. A few studies included in

an overview of (quasi-)experimental evaluation studies of school- this review assessed gender effects (e.g., Zander et al., 2014),

based arts education with pre-test post-test designs in order (mal-)nutrition (Bollimbala et al., 2019) and baseline levels

to identify what can be concluded from the evidence so far. of the outcome variable as moderators (Schellenberg et al.,

Given the small sample sizes prevalent in this research field, 2015).

this review focused on available and retrievable effect size

estimates and confidence intervals. While the focus on effect

sizes has significantly reduced the number of included studies, CONCLUSION

it allowed for a non-binary interpretation of the results, and the

application of caution in consideration of the (un)certainty of The present review systematically searched and summarized

evidence. From the narrative synthesis of the included studies, the evidence on the effects of arts education (namely music,

the review was able to summarize the limitations and gaps in the drama, dance, and visual arts) from quasi-experimental and

(quasi-)experimental research. experimental studies and critically discussed the evidence

Yet, this review has also some limitations that should be to date. Most included studies evaluated music programs,

considered. The formulation of the search strings may have while the evidence base for drama, dance and visual arts is

missed relevant studies. However, by screening previous reviews sparse. Largely, the number of studies and methodological

and additional publications by the authors of included papers, characteristics did not justify definite conclusions. Whereas

potential bias due to the search strategy was minimized as much experimental designs are considered the “gold standard” to

as possible. demonstrate causal impact, the present review has demonstrated

Furthermore, the selected inclusion and exclusion criteria that the “gold standard” is often associated with a range

pose some limitations with implications for the interpretation of methodological limitations which create uncertainty in

of the results. First, the small number of quantitative evaluation the conclusions. To support hypothesized mechanisms and

studies in the field made it impractical to further narrow the theory building, the inclusion of qualitative methods into field

selection down based on additional, albeit important design experiments seems a promising method as illustrated by a

(e.g., randomization, sample size, follow-up duration) or context few examples.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 10 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT FUNDING

The original contributions presented in the study are included We thank FernUniversität in Hagen for support of this work and

in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be its publication.

directed to the corresponding author/s.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The systematic review was conducted as part of the bachelor

AR and VS designed the review. VS was responsible thesis of the VS under the supervision of the AR.

for writing the initial and final version of the paper,

conducting the systematic searches, and completing data SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

extraction. AR supervised the study and contributed to

the discussion and during the paper writing process. Both The Supplementary Material for this article can be found

authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.

for publication. 2021.623935/full#supplementary-material

REFERENCES Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self

Determination in Human Behaviour. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Abedi, J. (2002). A latent-variable modeling approach to assessing reliability doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

and validity of a creativity instrument. Creat. Res. J. 14, 267–276. Degé, F., Wehrum, S., Stark, R., and Schwarzer, G. (2011). The influence of two

doi: 10.1207/S15326934CRJ1402_12 years of school music training in secondary school on visual and auditory

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory. Curr. Biol. 20, 136–140. memory. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 8, 608–623. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2011.590668

doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.014 Ewing, R. (2010). The Arts and Australian Education: Realising Potential.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a Social Cognitive Australian Education Review No. 58. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Council

Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. for Educational Research. Availble online at: http://research.acer.edu.au/aer/11

Bollimbala, A., James, P. S., and Ganguli, S. (2019). Impact of acute physical (accessed January 8, 2021).

activity on children’s divergent and convergent thinking: the mediating Fancourt, D., and Finn, S. (2019). What Is the Evidence on the Role of the

role of a low body mass index. Percept. Mot. Skills. 126, 603–622. Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review. Copenhagen:

doi: 10.1177/0031512519846768 WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network (HEN) synthesis

Bransford, J., and Schwartz, D. (1999). Chapter 3: rethinking transfer: a report 67). Availble online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/

simple proposal with multiple implications. Rev. Res. Educ. 24, 61–100. 10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf (accessed August 6, 2020).

doi: 10.3102/0091732X024001061 Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G∗ Power 3: a flexible

Brodsky, W., and Sulkin, I. (2011). Handclapping songs: a spontaneous platform statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical

for child development among 5–10-year-old children. Early Child Dev. Care. sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146

181, 1111–1136. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2010.517837 François, C., Chobert, J., Besson, M., and Schön, D. (2013). Music training

Brown, E. D., Garnett, M. L., Velazquez-Martin, B. M., and Mellor, T. J. (2018). for the development of speech segmentation. Cereb. Cortex. 23, 2038–2043.

The art of head start: Intensive arts integration associated with advantage in doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs180

school readiness for economically disadvantaged children. Early Child. Res. Q. Freeman, G. D., Sullivan, K., and Fulton, C. R. (2003). Effects of creative drama

45, 204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.12.002 on self-concept, social skills, and problem behavior. J. Educ. Res. 96, 131–138.

Bruner, J. (1966). Toward a Theory of Instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard doi: 10.1080/00220670309598801

University Press. Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., and Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect size estimates:

Bugos, J., and Jacobs, E. (2012). Composition instruction and cognitive current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141, 2–18.

performance: results of a pilot study. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 10:2. Available doi: 10.1037/a0024338

online at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/rime/vol10/iss1/2/ Galton, M., and Page, C. (2014). The impact of various creative initiatives on

Campbell, F. A., and Ramey, C. T. (1994). Effects of early intervention on wellbeing: a study of children in English primary schools. Cambridge J. Educ.

intellectual and academic achievement: a follow-up study of children from 45, 349–369. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2014.934201

low-income families. Child. Dev. 65, 684–698. doi: 10.2307/1131410 Göǧebakan, D. (2003). How students’ multiple intelligences differ in terms of

Catterall, J. (2002). “The arts and the transfer of learning,” in Critical Links: grade level and gender (Unpublished Master’s thesis), Middle East Technical

Learning in the Arts and Student Academic and Social Development, ed R. Deasy University, Ankara.

(Washington, DC: Arts Education Partnership), 151–157. Guo, X., Ohsawa, C., Suzuki, A., and Sekiyama, K. (2018). Improved

Catterall, J. S., and Peppler, K. A. (2007). Learning in the visual arts digit span in children after a 6-week intervention of playing a musical

and the worldviews of young children. Cambridge J. Educ. 37, 543–560. instrument: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 8, 1–9.

doi: 10.1080/03057640701705898 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02303

Cohen, J. W. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. Hardiman, M., Rinne, L., and Yarmolinskaya, J. (2014). The effects of arts

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. integration on long-term retention of academic content. Mind Brain Educ. 8,

Costa-Giomi, E. (1999). The effects of three years of piano instruction on children’s 144–148. doi: 10.1111/mbe.12053

cognitive development. J. Res. Music. Educ. 4, 198–212. doi: 10.2307/3345779 Hetland, L. (2000a). Learning to make music enhances spatial reasoning. J.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: The Experience of Play Aesthetic Educ. 34, 179–238. doi: 10.2307/3333643

in Work and Games. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Hetland, L. (2000b). Listening to music enhances spatial-temporal reasoning:

Deasy, R. J. (2002). Critical Links: Learning in the Arts and Student Academic and evidence for the “Mozart Effect”. J. Aesthetic Educ. 34, 105–148.

Social Development. Washington, DC: Arts Education Partnership. doi: 10.2307/3333640

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 11 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

Hetland, L., and Winner, E. (2001). The arts and academic achievement: creativitycultureeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/CCE-Literature-Review-

what the evidence shows. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 102, 3–6. Wellbeing-and-Creativity.pdf (accessed January 8, 2021).

doi: 10.1080/10632910109600008 McLellan, R., Galton, M., Steward, S., and Page, C. (2012b). The Impact of Creative

Hogenes, M., van Oers, B., Diekstra, R. F. W., and Sklad, M. (2016). The effects of Partnerships on the Wellbeing of Children and Young People. Newcastle: CCE.

music composition as a classroom activity on engagement in music education Availble online at: https://www.creativitycultureeducation.org//wp-content/

and academic and music achievement: a quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Music. uploads/2018/10/Impact-of-Creative-Partnerships-on-Wellbeing-Final-

Educ. 34, 32–48. doi: 10.1177/0255761415584296 Report-2012.pdf (accessed January 08, 2021).

Huron, D. (2001). Is music an evolutionary adaptation? Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 930, McLellan, R., Galton, M., and Walberg, M. (2015). The Impact of Arts Interventions

43–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05724.x on Health Outcomes – A Survey of Young Adolescents Accompanied by a

Institute for Arts Integration and STEAM. (2019). Is It Arts Integration or STEAM? Review of the Literature. Newcastle,: CCE. Availble online at: http://old.

Availble online at: https://artsintegration.com/2016/11/30/arts-integration- creativitycultureeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/HealthReport_Dec2014_

steam/ (accessed February 15, 2021). web.pdf [accessed February 21, 2021).

Jindal-Snape, D., Davies, D., Scott, R., Robb, A., Murray, C., and Harkins, C. McLellan, R., and Steward, S. (2014). Measuring children and young

(2018). Impact of arts participation on children’s achievement: A systematic people’s wellbeing in the school context. Cambridge J. Educ. 45, 307–332.

literature review. Think. Skills Creat. 29, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2018. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2014.889659

06.003 Moga, E., Burger, K., Hetland, L., and Winner, E. (2000). Does studying the arts

Jindal-Snape, D., Morris, J., Kroll, T., Scott, R., Toma, M., Levy, S.,. engender creative thinking? Evidence for near but not far transfer. J. Aesthetic

et al. (2014a). A Narrative Synthesis of Evidence Relating to the Impact Educ. 34, 91–104. doi: 10.2307/3333639

of Arts and Community-Based Arts Interventions on Health, Wellbeing Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and The, PRISMA

and Educational Attainment. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews

Health. Availble online at: https://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/4510/GCPH_ and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097.

Narrative_Synthesis_WP1__2___3.pdf (accessed June 24, 2020). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Jindal-Snape, D., Scott, R., and Davies, D. (2014b). ‘Arts and Smarts’: Morris, S. B. (2008). Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group

Assessing the Iimpact of Arts Participation on Academic Performance designs. Organ. Res. Methods. 11, 364–386. doi: 10.1177/1094428106291059

During School Years. Glasgow: Glasgow Centre for Population Health. Oxford University Press (2019). “Art”. Lexico.com. Availble online at: https://www.

Availble online at: https://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/4512/GCPH__Arts_ lexico.com/definition/art. (accessed June 24, 2020).

and_Smarts__Sys_Review_WP2.pdf (accessed June 24, 2020). Paluck, E. L. (2010). The promising integration of qualitative methods

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success and field experiments. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 628, 59–71.

story: social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educ. Res. 38, doi: 10.1177/0002716209351510

365–379. doi: 10.3102/0013189X09339057 Perignat, E., and Katz-Buonincontro, J. (2019). STEAM in practice and

Keinänen, M., Hetland, L., and Winner, E. (2000). Teaching cognitive skill through research: an integrative literature review. Think Skills Creat. 31, 31–43.

dance: evidence for near but not far transfer. J. Aesthetic Educ. 34, 295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2018.10.002

doi: 10.2307/3333646 Pietschnig, J., Voracek, M., and Formann, A. K. (2010). Mozart effect–Shmozart

Köksal Akyol, A. (2018). Examination of the effect of drama education on effect: a meta-analysis. Intelligence 38, 14–323. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2010.03.001

multiple intelligence areas of children. Early Child Dev. Care. 188, 157–167. Podlozny, A. (2000). Strengthening verbal skills through the use of classroom

doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1207635 drama: a clear link. J. Aesthetic Educ. 34, 239–275. doi: 10.2307/33

Kreutzmann, M., Zander, L., and Webster, G. D. (2018). Dancing is belonging! 33644

How social networks mediate the effect of a dance intervention on students’ Rabinowitch, T. C., Cross, I., and Burnard, P. (2013). Long-term musical group

sense of belonging to their classroom. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 240–254. interaction has a positive influence on empathy in children. Psychol. Music. 41,

doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2319 484–498. doi: 10.1177/0305735612440609

Lakens, D., and Evers, E. R. K. (2014). Sailing from the seas of chaos Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., and Ky, C. N. (1993). Music and spatial task

into the corridor of stability: practical recommendations to increase performance. Nature 365:611. doi: 10.1038/365611a0

the informational value of studies. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 278–292. Rickard, N. S., Bambrick, C. J., and Gill, A. (2012). Absence of

doi: 10.1177/1745691614528520 widespread psychosocial and cognitive effects of school-based music

Latané, B., Liu, J. H., Nowak, A., Bonevento, M., and Zheng, L. (1995). Distance instruction in 10–13-year-old students. Int. J. Music. Educ. 30, 57–78.

matters: physical space and social impact. Personal Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, doi: 10.1177/0255761411431399

795–805. doi: 10.1177/0146167295218002 Rickard, N. S., Vasquez, J. T., Murphy, F., Gill, A., and Toukhsati, S. R. (2010).

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Egitimate Benefits of a classroom based instrumental music program on verbal memory

Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. of primary school children: a longitudinal study. Aust. J. Music Educ. 1, 36–47.

doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355 Roden, I., Grube, D., Bongard, S., and Kreutz, G. (2014a). Does music

Lee, B. K., Patall, E. A., Cawthon, S. W., and Steingut, R. R. (2015). The effect training enhance working memory performance? Findings from a

of drama-based pedagogy on PreK−16 outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 85, 3–49. quasi-experimental longitudinal study. Psychol. Music. 42, 284–298.

doi: 10.3102/0034654314540477 doi: 10.1177/0305735612471239

Lenhard, W., and Lenhard, A. (2016). Calculation of Effect Sizes. [Online Roden, I., Könen, T., Bongard, S., Frankenberg, E., Friedrich, E. K., and Kreutz, G.

calculator]. Dettelbach: Psychometrica. Availble online at: https://www. (2014b). Effects of music training on attention, processing speed and cognitive

psychometrica.de/effekt_size.html (accessed June 24, 2020). music abilities—findings from a longitudinal study. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 28,

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. 545–557. doi: 10.1002/acp.3034

P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and Roden, I., Kreutz, G., and Bongard, S. (2012). Effects of a school-

meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and based instrumental music program on verbal and visual memory in

elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 primary school children: a longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 3:572.

Mason, S., Tovey, P., and Long, A. F. (2002). Evaluating complementary medicine: doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00572

methodological challenges of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 325, 832–834. Roden, I., Zepf, F., d., Kreutz, G., Grube, D., and Bongard, S. (2016). Effects of

doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7368.832 music and natural science training on aggressive behavior. Learn. Instr. 45,

McCarthy, K. F., Ondaatje, E. H., Zakaras, L., and Brooks, A. (2004). Gifts of the 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.07.002

Muse: Reframing the Debate About the Benefits of the Arts. Santa Monica, CA: Rychen, D. S., and Salganik, L. H. (eds.). (2003). Key Competencies for a Successful

Rand Corporation. doi: 10.7249/MG218 Life and a Well-Functioning Society. Göttingen: Hogrefe and Huber.

McLellan, R., Galton, M., Steward, S., and Page, C. (2012a). The Impact of Schellenberg, E. G. (2004). Music lessons enhance IQ. Psychol. Sci. 15, 511–514.

Creative Initiatives on Wellbeing. Newcastle: CCE. Availble online at: http://old. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00711.x

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 12 April 2021 | Volume 12 | Article 623935

Schneider and Rohmann Arts in Education

Schellenberg, E. G., Corrigall, K. A., Dys, S. P., and Malti, T. (2015). Group Vygotsky, L. S. (1977). The development of higher psychological functions. Sov.

music training and children’s prosocial skills. PLoS ONE 10:e0141449. Rev. 18, 38–51. doi: 10.2753/RSS1061-1428180338

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141449 Walsh, R. T., Richardson, M. A., and Cardey, R. M. (1991). Structured fantasy

Schulz, K. F., and Grimes, D. A. (2002). Sample size slippages in randomised approaches to children’s group therapy. Soc. Work Groups. 14, 57–73.