Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Italian Institute Sience 2

Italian Institute Sience 2

Uploaded by

Branislav Namen0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pages1) In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire was facing increasing invasions from Germanic tribes but still maintained control over Italy.

2) Power struggles emerged between civil and military leaders in Italy, with emperors becoming pawns amid the military crisis.

3) Figures like Aetius, Ricimer, and Odoacer rose to power and controlled armies with growing non-Roman elements, pushing the politics towards rule without Roman emperors, though maintaining defenses of Italy.

Original Description:

fxfrr

Original Title

ItalianInstituteSience2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1) In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire was facing increasing invasions from Germanic tribes but still maintained control over Italy.

2) Power struggles emerged between civil and military leaders in Italy, with emperors becoming pawns amid the military crisis.

3) Figures like Aetius, Ricimer, and Odoacer rose to power and controlled armies with growing non-Roman elements, pushing the politics towards rule without Roman emperors, though maintaining defenses of Italy.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesItalian Institute Sience 2

Italian Institute Sience 2

Uploaded by

Branislav Namen1) In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire was facing increasing invasions from Germanic tribes but still maintained control over Italy.

2) Power struggles emerged between civil and military leaders in Italy, with emperors becoming pawns amid the military crisis.

3) Figures like Aetius, Ricimer, and Odoacer rose to power and controlled armies with growing non-Roman elements, pushing the politics towards rule without Roman emperors, though maintaining defenses of Italy.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Italyin heearly Middle Ages

The Roman Empire was an international political system in which Italy was only a

part, though an important part. When the empire fell, a series of barbarian kingdoms

initially ruled the peninsula, but, after the Lombard invasion of 568–569, a network

of smaller political entities arose throughout Italy. How each of these developed—in

parallel with the others, out of the ruins of the Roman world—is one principal theme

of this section. The survival and development of the Roman city is another. The

urban focus of politics and economic life inherited from the Romans continued and

expanded in the early Middle Ages and was the unifying element in the development

of Italy’s regions.

The late Roman Empire and the Ostrogoths

mosaic

Diocletian

The military emperors of the late 3rd century, most notably Diocletian (284–305),

reformed the political structures of the Roman Empire. They restructured the army

after the disasters of the previous 50 years, extensively developed the

civil bureaucracy and the ceremonial rituals of imperial rule, and, above all,

reorganized and enlarged the tax system. The fiscal weight of the late Roman Empire

was heavy, given the resources of the period: its major support, the land tax,

collected by local city governments, took at least one-fifth, and probably one-third, of

the agricultural produce. On the other hand, the administration and the army that

the tax system paid for reestablished a measure of stability for the empire in the 4th

century. Central government was not always stable; there were several periods of

civil war in the 4th century, notably in the decade after Diocletian’s retirement and in

the years around 390. But succession disputes had been a normal part of imperial

politics since the Julio-Claudians in the 1st century CE; in general, self-confidence in

the 4th-century empire was fairly high. Aggressive emperors such as Valentinian

I (364–375) could not have imagined that within a century nearly all of the Western

Empire was to be under barbarian rule. Nor was this lack of a sense of doom a simple

delusion; after all, in the richer Eastern provinces the imperial system held firm for

many centuries, in the form of the Byzantine Empire.

Fifth-century political trends

The Germanic invasions of the years after 400 did not, then, strike at an enfeebled

political system. But in facing them, ultimately unsuccessfully, Roman emperors and

generals found themselves in a steadily weaker position, and much of

the coherence of the late Roman state dissolved in the environment of the continuous

emergencies of the 5th century. One of the tasks of the historian must be to assess the

extent of the survival of Roman institutions in each of the regions of the West

conquered by the Germans, for this varied greatly. It was considerable in the North

Africa of the Vandals, for example, as Africa was a rich and stable province and was

conquered relatively quickly (429–442); it was more limited in northern Gaul, a less

Romanized area to begin with, which experienced 80 years of war and confusion

(406–486) before it finally came under the control of the Franks. In Italy the 4th-

century system remained relatively unchanged for a long time. The government of

the Western Empire, which was permanently based at Ravenna after 402, became

progressively weaker but remained substantially intact. While the Germanic

king Odoacer ruled Italy after 476, the peninsula was not conquered by a Germanic

tribe until the Ostrogothic invasion in 489–493. Although the peninsula had faced

invasions, such as those of Alaric the Visigoth in 401–410, Italian politics continued

during the 5th century to be those of the Roman Empire. This meant, in

the context of the military crisis of the period, a continual struggle between civil and

military leaders, with the emperors themselves more or less pawns in the middle.

The careers of three of these leaders serve as examples of 5th-century political

trends. Aetius controlled the armies of the West between 429 and his murder in 454;

he was the last man to be active in both Italy and Gaul, as a Roman senatorial leader

of a barbarian army that was Germanic, Hunnic, or both. His career was typical of

those in the military tradition of Roman politics, and, had his life not been cut short,

he might well have become emperor. The makeup of his army was, however, already

significantly different from that of Diocletian or Valentinian, and its growing number

of non-Roman military detachments tended increasingly to have their own ethnic

leaders and to be organized according to their own rules. Ricimer (in power 456–

472, by this time only in Italy) was a Germanic tribesman, not a Roman. He was

culturally highly Romanized and, as such, was himself part of a tradition of Romano-

Germanic military leadership that went back to the 370s, but he could not, as a

“barbarian,” be emperor, and he made and unmade several emperors in a search for

a stable ruler who would not undermine his own power. Significantly, in 456–457

and 465–467 he ruled alone, subordinate only to the Eastern emperor in

Constantinople. Odoacer was militarily supreme from 476 to 493. In a coup in 476 he

replaced the last ethnic-Roman military commander, Orestes, and deposed Orestes’

son, Romulus Augustulus, the child emperor and the last of the Western emperors.

Odoacer pushed Ricimer’s politics to its logical conclusion and ruled without an

emperor except for the nominal recognition of Constantinople as supreme authority.

Odoacer, however, did not merely call himself patricius—local ruler for the Eastern

Empire—but also rex—king of his Germanic army of Sciri, Rugians, and Heruls. To

what extent he was a military commander of a Roman army as opposed to being a

German “tribal” leader was by now impossible to tell. Nonetheless, he, like Ricimer,

was an effective defender of Italy against invaders for a long time.

You might also like

- Summary of The Romanovs: by Simon Sebag Montefiore | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of The Romanovs: by Simon Sebag Montefiore | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Rome New York FaziosDocument30 pagesRome New York Faziossaintstephen11No ratings yet

- 8 Reasons Why Rome FellDocument7 pages8 Reasons Why Rome FellN_Athar_ZamanNo ratings yet

- ESO 2 Essential Geography and History Unit 1Document17 pagesESO 2 Essential Geography and History Unit 1Nataliasol07No ratings yet

- Italy - HistoryDocument218 pagesItaly - HistoryLily lolaNo ratings yet

- OlaszorszagDocument18 pagesOlaszorszaghumblenderNo ratings yet

- Identification and Reasons For The Fall of The Roman EmpireDocument12 pagesIdentification and Reasons For The Fall of The Roman EmpireMuhamma Ibrahim AbbasiNo ratings yet

- ERUEL ANDREY ESCAREZ - Multicultural Diversity in Workplace For Tourism ProfessionalsDocument6 pagesERUEL ANDREY ESCAREZ - Multicultural Diversity in Workplace For Tourism ProfessionalsANDREY EscarezNo ratings yet

- Stilicho, The Rise of The Magister Utriusque Militiae and The Path To Irrelevancy of The Position of Western EmperorDocument93 pagesStilicho, The Rise of The Magister Utriusque Militiae and The Path To Irrelevancy of The Position of Western EmperorcaracallaxNo ratings yet

- The Fall of RomeDocument12 pagesThe Fall of RomeKashigiNo ratings yet

- Rome EmpireDocument70 pagesRome EmpireTania SmithNo ratings yet

- Eastern Rome and The WestDocument10 pagesEastern Rome and The WestNəzrin HüseynovaNo ratings yet

- The Fall of Roman EmpireDocument4 pagesThe Fall of Roman EmpireHessel Juliust Wongkaren100% (1)

- Roman CrisisDocument5 pagesRoman CrisisVaibhavi PandeyNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Romanovs: by Simon Sebag Montefiore | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of The Romanovs: by Simon Sebag Montefiore | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Sofo E-Content Crisis of Roman Empire - I Unit I 03.04.2020Document6 pagesSofo E-Content Crisis of Roman Empire - I Unit I 03.04.2020Aryabhatta CollegeNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Roman Military 4th Century ADDocument76 pagesAnalysis of The Roman Military 4th Century ADStanisław Disę100% (1)

- Origins of The Roman EmpireDocument3 pagesOrigins of The Roman EmpireNaveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Roman EmpireDocument6 pagesRoman Empireeyob girumNo ratings yet

- The Roman Empire: The History of Ancient Rome: The Story of Rome, #2From EverandThe Roman Empire: The History of Ancient Rome: The Story of Rome, #2No ratings yet

- Roman Empire or The Fall of Rome) Was The Loss of CentralDocument35 pagesRoman Empire or The Fall of Rome) Was The Loss of CentralSashimiTourloublancNo ratings yet

- Fall of Román EmpireDocument2 pagesFall of Román EmpireLucciana GómezNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For The Fall of The Roman EmpireDocument8 pagesThesis Statement For The Fall of The Roman EmpireGhostWriterForCollegePapersUK100% (2)

- History Study GuideDocument1 pageHistory Study Guide00jab00No ratings yet

- Fall of Roman EmpireDocument12 pagesFall of Roman EmpireAnand JhaNo ratings yet

- INTRO WCL The Middle AgesDocument3 pagesINTRO WCL The Middle AgesSar AhNo ratings yet

- MYP3 GH U1 NotesDocument7 pagesMYP3 GH U1 NotestufygiuohiNo ratings yet

- A Review Essay of Escape From RomeDocument27 pagesA Review Essay of Escape From RomemarvinmartesNo ratings yet

- FeudalismDocument2 pagesFeudalismbhagyalakshmipranjanNo ratings yet

- The Middle AgesDocument150 pagesThe Middle AgesCintia RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Western Roman EmpireDocument6 pagesWestern Roman EmpireSebastián Leonetti BernhardtNo ratings yet

- REDocument2 pagesREAlexandruNo ratings yet

- The Holy Roman EmpireDocument10 pagesThe Holy Roman EmpireJuan Felipe Hernandez ArangoNo ratings yet

- The Empire Was Considered by The Roman Catholic CHDocument2 pagesThe Empire Was Considered by The Roman Catholic CHrhaellmar gabaldonNo ratings yet

- Roman EmpireDocument66 pagesRoman EmpireMathieu RB100% (1)

- Western Roman EmpireDocument37 pagesWestern Roman EmpireSashimiTourloublancNo ratings yet

- The Lombard LawsDocument305 pagesThe Lombard LawsJake Sal100% (2)

- Roman EmpireDocument1 pageRoman EmpireRlakemeNo ratings yet

- Basileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-: RomanizedDocument2 pagesBasileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-: RomanizedRaul EnicaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document14 pagesChapter 3Ramón del Buey CañasNo ratings yet

- A 1Document68 pagesA 1abcd efghNo ratings yet

- John Vincent Palatine - The Gothic Wars - (Retrieved - 03.09.2020)Document14 pagesJohn Vincent Palatine - The Gothic Wars - (Retrieved - 03.09.2020)JWNo ratings yet

- New Kingdoms and Byzantine RevivalDocument9 pagesNew Kingdoms and Byzantine RevivalGeorgiana Diana MindrilaNo ratings yet

- A Century of Crisis. Historians Generally Agree That The End of The Reign of TheDocument3 pagesA Century of Crisis. Historians Generally Agree That The End of The Reign of TheMarta DemchukNo ratings yet

- Roman EmpireDocument6 pagesRoman EmpireROUIDJI YoucefNo ratings yet

- Basileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-: RomanizedDocument2 pagesBasileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-: RomanizedAnnabelle ArtiagaNo ratings yet

- 8 Reasons Why Rome Fell - HISTORYDocument5 pages8 Reasons Why Rome Fell - HISTORYAeheris BlahNo ratings yet

- Roman EmpireDocument5 pagesRoman EmpireAnushree KulshreshthaNo ratings yet

- Roman EmpireDocument4 pagesRoman EmpireKiran AsifNo ratings yet

- The Fall of The Roman EmpireDocument3 pagesThe Fall of The Roman Empireapi-234908816No ratings yet

- Roman History Compact & Easy to Understand Experience Ancient Rome From Its Birth to Its Fall - Incl. Roman Empire Background KnowledgeFrom EverandRoman History Compact & Easy to Understand Experience Ancient Rome From Its Birth to Its Fall - Incl. Roman Empire Background KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- Roman EmpireDocument2 pagesRoman EmpireeloraNo ratings yet

- The Byzantine EmpireDocument25 pagesThe Byzantine EmpirekjrazoNo ratings yet

- Imperium Rōmānum, Basileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-:: RomanizedDocument2 pagesImperium Rōmānum, Basileía Tōn Rhōmaíōn) Was The Post-:: RomanizedPatrickBulawanNo ratings yet

- Unit-17 Religion, State and SocietyDocument20 pagesUnit-17 Religion, State and SocietysaithimranadnanNo ratings yet

- Lombard Kingdom Tuscany Pavia Verona Milan Turin Lucca Friuli Avars Spoleto BeneventoDocument1 pageLombard Kingdom Tuscany Pavia Verona Milan Turin Lucca Friuli Avars Spoleto BeneventoBranislav NamenNo ratings yet

- Italian Institute Sience 3Document1 pageItalian Institute Sience 3Branislav NamenNo ratings yet

- Italian Institute SienceDocument2 pagesItalian Institute SienceBranislav NamenNo ratings yet

- THGDRGHTRTGRDocument1 pageTHGDRGHTRTGRBranislav NamenNo ratings yet

- Bostan e AuliyaDocument194 pagesBostan e AuliyaRazaNo ratings yet

- Feudalism - Nikhil PandhiDocument17 pagesFeudalism - Nikhil PandhiRohit GunasekaranNo ratings yet

- Ammianus and Theodosius I Concerning THDocument47 pagesAmmianus and Theodosius I Concerning THbela977No ratings yet

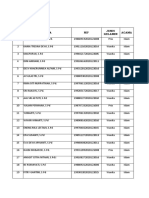

- Nom Latsar CPNS Kab. Garut 2021Document28 pagesNom Latsar CPNS Kab. Garut 2021Awayz NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Tasheel ul Ansha تسہیل الانشاءDocument178 pagesTasheel ul Ansha تسہیل الانشاء20020920-030No ratings yet

- Spain in The Middle AgesDocument12 pagesSpain in The Middle AgesAtna25No ratings yet

- Heather Goths and Romans 1991Document10 pagesHeather Goths and Romans 1991grzejnik1No ratings yet

- Usurpers and Tyrants of Arthurian BritainDocument4 pagesUsurpers and Tyrants of Arthurian BritainDeborah ShepherdNo ratings yet

- Holy Roman EmpireDocument17 pagesHoly Roman EmpireaquaelNo ratings yet

- Data Warga RT 01 2023Document16 pagesData Warga RT 01 2023fawazrasyid737No ratings yet

- Byzantine EmpireDocument59 pagesByzantine EmpireNirmal BhowmickNo ratings yet

- Germanic Invasions and Collapse of The Western EmpireDocument4 pagesGermanic Invasions and Collapse of The Western EmpireRavi Kumar NadarashanNo ratings yet

- KHULASA SHARAH AQAID خلاصہ شرح عقائدDocument206 pagesKHULASA SHARAH AQAID خلاصہ شرح عقائدyasirraxa25No ratings yet

- Medieval Period (4th - 15th Century) : Byzantine Greece Frankokratia Byzantine Empire Fourth CrusadeDocument2 pagesMedieval Period (4th - 15th Century) : Byzantine Greece Frankokratia Byzantine Empire Fourth CrusadeAlicia NhsNo ratings yet

- The Ethnology of GermanyDocument26 pagesThe Ethnology of GermanyMariusz KairskiNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pemilih Sementara Pemilihan Ketua RT 14/01 TAHUN 2022Document9 pagesDaftar Pemilih Sementara Pemilihan Ketua RT 14/01 TAHUN 2022Raudatul JanahNo ratings yet

- Early History of The Roman EmpireDocument18 pagesEarly History of The Roman EmpireKai GrenadeNo ratings yet

- The End of Roman BritainDocument2 pagesThe End of Roman BritainMaria de los Angeles SoriaNo ratings yet

- Barbarian Kingdoms PDFDocument3 pagesBarbarian Kingdoms PDFPaul CerneaNo ratings yet

- 2.1 Anglo-Saxon Period, HiB&US, Lecture WorksheetDocument1 page2.1 Anglo-Saxon Period, HiB&US, Lecture WorksheetAdrien BaziretNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture: Unit II. Early Midieval PeriodDocument25 pagesHistory of Architecture: Unit II. Early Midieval PeriodDesign FacultyNo ratings yet

- The ReconquistaDocument5 pagesThe ReconquistaCamila Gisselle Martínez CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Fall of The Roman EmpireDocument3 pagesFall of The Roman EmpireHasnae BendaragNo ratings yet

- Medieval History - Oxford Big Ideas 8Document21 pagesMedieval History - Oxford Big Ideas 8ceriwilliams62No ratings yet

- The Visigoths: Andrea Martín Bravo - 2ºC 1Document26 pagesThe Visigoths: Andrea Martín Bravo - 2ºC 1Mariagar1973100% (1)

- Banditry or CatasthropeDocument17 pagesBanditry or CatasthropeMarcosThomasPraefectusClassisNo ratings yet

- Attila The HunDocument42 pagesAttila The HunJames BrownNo ratings yet

- History of Design: Early Christian and Byzantine ArchitectureDocument37 pagesHistory of Design: Early Christian and Byzantine ArchitecturePrashant TiwariNo ratings yet