0% found this document useful (0 votes)

187 views9 pagesJosie King's Medication Error Analysis

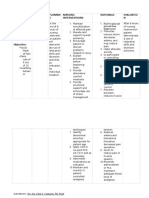

This document presents a root cause analysis and safety improvement plan related to a medication error that resulted in the death of an 18-month old child, Josie King. The root causes identified include lack of communication between the nurse and doctor regarding the child's condition, the nurse not properly verifying medication orders, and the mother's lack of understanding of her rights as a patient. The improvement plan proposes strategies to address human factors like fatigue, improve communication among healthcare providers, implement daily medication timeouts, provide additional training to nurses, and establish protocols to reduce distractions during medication administration. The goal is to minimize medication errors by enhancing healthcare workers' skills and modifying the clinical environment.

Uploaded by

akko aliCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

187 views9 pagesJosie King's Medication Error Analysis

This document presents a root cause analysis and safety improvement plan related to a medication error that resulted in the death of an 18-month old child, Josie King. The root causes identified include lack of communication between the nurse and doctor regarding the child's condition, the nurse not properly verifying medication orders, and the mother's lack of understanding of her rights as a patient. The improvement plan proposes strategies to address human factors like fatigue, improve communication among healthcare providers, implement daily medication timeouts, provide additional training to nurses, and establish protocols to reduce distractions during medication administration. The goal is to minimize medication errors by enhancing healthcare workers' skills and modifying the clinical environment.

Uploaded by

akko aliCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd