Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pettit Western 2004

Uploaded by

Suhail AhmedCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pettit Western 2004

Uploaded by

Suhail AhmedCopyright:

Available Formats

Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S.

Incarceration

Author(s): Becky Pettit and Bruce Western

Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 69, No. 2 (Apr., 2004), pp. 151-169

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3593082 .

Accessed: 01/04/2013 22:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Sociological Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Mass Imprisonmentand the LifeCourse:

Raceand Class Inequalityin U.S. Incarceration

Becky Pettit Bruce Western

Universityof Washington PrincetonUniversity

Althoughgrowthin the prisonpopulationoverthepast twenty-fiveyears has been

U.S. examinechangesin inequalityin imprisonment.Westudy

widelydiscussed,few studies

penal inequalityby estimatinglifetimerisksof imprisonmentfor blackand whitemenat

different levels of education. survey,and censusdata, we

Combiningadministrative,

estimatethatamongmenbornbetween1965 and 1969, 3 percentof whitesand 20

percentofblacks had servedtimeinprison by theirearlythirties.Therisksof

incarcerationare highlystratifiedby education.Amongblackmenbornduringthis

period, 30percentof thosewithoutcollege educationand nearly60percentof high

school dropoutswenttoprison by 1999. Thenovelpervasivenessof imprisonment

indicatesthe emergenceof incarcerationas a newstage in the life courseofyoung low-

skill blackmen.

growth of the American part of the early adulthood for black men in

Hastemtheover penal sys-

the past thirtyyears transformed poor urban neighborhoods (Freeman 1996;

the path to adulthood followed by disadvan- Irwin andAustin 1997). In this period of mass

taged minority men? Certainlythe prisonboom imprisonment,it was argued,official criminal-

affectedmanyyoungblackmen. The U.S. penal ity attachednotjust to individualoffenders,but

populationincreasedsix fold between 1972 and to whole social groups defined by their race,

2000, leaving 1.3 million men in state and fed- age, and class (Garland2001a:2).

eralprisonsby the end of the century.By 2002, Claims for the new ubiquity of imprison-

around 12 percent of black men in their twen- ment acquire added importancegiven recent

ties were in prisonorjail (HarrisonandKarberg research on the effects of incarceration.The

2003). High incarcerationratesled researchers persistent disadvantage of low-education

to claim thatprisontime had become a normal AfricanAmericansis, however,usually linked

not to the penal system but to large-scalesocial

forces like urbandeindustrialization, residential

segregation, or wealthinequality(Wilson 1987;

Direct all correspondence to Becky Pettit,

Department of Washington, Massey and Denton 1993; Oliver and Shapiro

of Sociology,University

202 SaveryHall,Box 353340,Seattle,WA98195- 1997). However,evidence shows incarceration

3350(bpettit@u.washington.edu) orBruceWestern, is closely associated with low wages, unem-

Departmentof Sociology,PrincetonUniversity, ployment, family instability, recidivism, and

PrincetonNJ08544(westem@princeton.edu). Drafts restrictions on political and social rights

of thispaperwerepresentedat theannualmeetings (Western,Kling andWeiman2000; Haganand

of thePopulation Associationof America,2001and Dinovitzer 1999; Sampson and Laub 1993;

theAmericanSociologicalAssociation,2001.This Uggen andManza2002; Hirschet al. 2002). If

research was supported by the Russell Sage indeed imprisonment became commonplace

Foundationand grant SES-0004336 from the and men

NationalScienceFoundation. Wegratefullyacknowl- amongyoung disadvantaged minority

in the DevianceWorkshop at the through the 1980s and 1990s, a varietyof other

edge participants

social inequalities may have deepened as a

Universityof Washington, AngusDeaton,Robert

Lalonde,Steve Levitt,Ross MacMillan,Charlie result.

Hirschman,andASR reviewersfor helpfulcom- Althoughdeepeninginequalityin incarcera-

mentson thispaper. tion and the pervasive imprisonment of

SOCIOLOGICAL

AMERICAN VOL.69 (April:151-169)

REVIEW,2oo004,

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

152 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

disadvantagedmen is widely asserted,thereare 1997 had committed homicide, rape, or rob-

few systematicempiricaltests.To studyhow the bery, while property and drug offenders each

prison boom may have reshapedthe life paths accountedfor one-fifth of all state inmates.In

of young men, we estimate the prevalence of thatsame year,more than60 percentof Federal

imprisonmentand its distributionamongblack prisoners were serving time for drug crimes

andwhitemen, aged 15 to 34, between1979 and (Maguire and Pastore 2001: 519). Nearly all

1999.Wealso comparetheprevalenceof impris- prisoners serve a minimum of one year, with

onmentto otherlife events-college graduation state drugoffendersin 1996 servingjust over2

and military service-that are more common- years on average,comparedto over 11 yearsfor

ly thoughtto markthe path to adulthood. murderers. In federal prison, average time

Many have studied variation in imprison- served for drug offenders was 40 months in

ment but our analysis departs from earlier 1996 (Blumsteinand Beck 1999:36, 49). These

research in two ways. First, the risk of incar- lengthy periods of confinementare distributed

cerationis usuallymeasuredby an incarceration unequallyacross the population:More than90

rate-the overnightcount of the penal popula- percentof prisonersaremen, incarceration rates

tion as a fraction of the total population(e.g., for blacks are about eight times higher than

Sutton 2000; Jacobs and Helms 1996). Much those forwhites,andprisoninmatesaverageless

like college graduationor militaryservicehow- than 12 years of completed schooling.

ever, having a prison record confers a persist-

ent status that can significantly influence life RACEAND CLASSINEQUALITY

trajectories. Our analysis estimates how the

cumulativerisk of incarcerationgrows as men High incarcerationratesamong black andlow-

age from theirteenage years to their earlythir- education men have been traced to similar

ties. To contrastthe peak of the prisonboom in sources. The slim economic opportunitiesand

the late 1990s with the penal system of the late turbulentliving conditionsof young disadvan-

1970s, cumulative risks of imprisonmentare taged and black men may lead them to crime.

calculated for successive birth cohorts, born In addition,elevatedratesof offending in poor

1945-49 to 1965-69. Second, although eco- andminorityneighborhoodscompoundthe stig-

nomic inequality in imprisonmentmay have ma of social marginalityandprovokethe scruti-

increased,most empiricalresearchjust examines ny of criminaljustice authorities.

racial disparity (e.g., Blumstein 1993; Mauer Research on carceral inequalities usually

1999;Bridges,Crutchfield,andPitchford1994). examinesracialdisparityin stateimprisonment.

To directlyexaminehow theprisonboom affect- The leading studies of Blumstein(1982, 1993)

ed low-skill black men, our analysis estimates find that arrestrates-particularly for serious

imprisonmentrisks at different levels of edu- offenses like homicide-explain a large share

cation. Evidence that imprisonment became of the black-whitedifference in incarceration.

disproportionately widespreadamonglow-edu- Because police arrestsreflectcrime in the pop-

cation black men strengthensthe case that the ulation and policing effort, arrestrates are an

penal system has become an importantnew imperfect measure of criminal involvement.

featureof Americanrace and class inequality. More directmeasurementof the race of crimi-

nal offenders is claimed for surveys of crime

victims who reportthe race of their assailants.

IMPRISONMENTAND INEQUALITY

Victimization data similarly suggest that the

The full extent of the prisonboom can be seen disproportionate involvementof blacksin crime

in a long historicalperspective.Between 1925 explains most of the racial disparityin incar-

and 1975, the prisonincarcerationratehovered ceration(Langan 1985). These results are but-

around 100 per 100,000 of the residentpopu- tressedby researchassociatingviolentandother

lation. By 2001, the imprisonmentrate, at 472 crime in blackneighborhoodswithjoblessness,

per 100,000, approached5 times its historic family disruption, and neighborhoodpoverty

average.The prisonersreflectedin these statis- (e.g., CrutchfieldandPitchford1997;Messner

tics account for two-thirds of the U.S. penal et al. 2001; LaFreeand Drass 1996; Morenoff

population, the remainderbeing held in local et al. 2001; see the review of Sampson and

jails. In 1997, abouta thirdof stateprisonersin Lauritsen 1997). In short, most of the racial

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACEAND CLASS INEQUALITYIN U.S. INCARCERATION 153

disparityin imprisonmentis attributedto high therefore result from high crime rates among

black crime rates for imprisonable offenses young men with little schooling.

(Tonry 1995, 79). As for racial minorities, researchers also

Althoughcrimeratesmay explainas muchas arguethatthe poor areperceivedas threatening

80 percent of the disparity in imprisonment to social orderby criminaljustice officials (e.g.,

(Tonry1995),a significantresidualsuggeststhat Rusche and Kirchheimer1968; Spitzer 1975;

blacks are punitively policed, prosecuted,and Jacobs and Helms 1996). The poor thus attract

sentenced.Sociologists of punishmentlink this the disproportionateattention of authorities,

differentialtreatmentto official perceptionsof either in the way criminal law is written or

blacks as threatening or troublesome (Tittle applied by police and the courts. Consistent

1994). The racial threat theory is empirically with this view, time series of incarcerationrates

supportedby researchon sentencingand incar- are correlated with unemployment rates and

ceration rates. Strongest evidence for racially othermeasuresof economic disadvantage,even

differentialtreatmentis foundfor some offens- after crime rates are controlled (Chiricos and

es and in some jurisdictionsratherthan at the Delone 1992). Few studies focus on education,

aggregatelevel. AfricanAmericansare at espe- as we do, but class bias in criminalsentencing

cially high risk of incarceration, given their is suggested by findings that more educated

arrest rates, for drug crimes and burglary federaldefendantsreceive relativelyshort sen-

(Blumstein 1993). Stateswith largewhite pop- tences in general,andareless likely to be incar-

ulationsalso tendto incarcerateblacksat a high cerated for drug crimes (Steffensmeier and

rate,controllingforrace-specificarrestratesand Demuth 2000). Thus, imprisonment may be

demographicvariables(Bridges et al. 1994). A more common among low-education men

large residualracial disparityin imprisonment because they are the focus of the social control

thus appearsdue to the differentialtreatmentof efforts of criminaljustice authorities.

AfricanAmericansby police and the courts.

Similar to the analysis of race, class dis-

INEQUALTYAND THE PRISON BOOM

paritiesmay also be rooted in patternsof crime

and criminalprocessing. Ouranalysis captures While researchon offending and incarceration

class divisions with a measure of educational explains race and class inequalitiesin impris-

attainment. Education, of course, correlates onment at a point in time, these inequalities

with measuresof occupationand employment may have sharpenedoverthe lastthirtyyearsas

statusthatmore commonly featurein research prisons grew.Some claim thatcriminaloffend-

on class andcrime (for reviews see Braithwaite ing at the bottom of the social hierarchyrose

1979; Hagan, Gillis, and Brownfield 1996). with the depletionof economic opportunitiesin

Just as the social strain of economic disad- inner cities. Others argue that punitive drug

vantagemay push the poor into crime (Merton policy and tough-on-crimejustice policy-the

1968; Clowardand Ohlin 1960), those with lit- wars on drugsandcrime-affected mostly low-

tle schooling also experience frustration at skill minoritymen.

blocked opportunities. Time series analysis Increasingcrime among low-educationmen

shows that levels of schooling significantly is often seen to result from declining econom-

affect race-specific arrest rates (LaFree and ic opportunitiesfor unskilled workers.Urban

Drass 1996). While a good proxy for economic ethnographersmakethis case in studiesof drug-

status, school failure also contributesdirectly relatedgang activity(e.g., VenkateshandLevitt

to delinquency.Whethercrime is producedby 1998; Bourgois 1995). Severalresearchersalso

the oppositionalsubcultureof school dropouts, link growing crime in poor urban neighbor-

as Cohen (1955) suggests, or by weakened hoods to increased rates of imprisonment.

networks of informal social control (Hagan Freeman(1996) arguedthat young black men

1993), poor academic performanceand weak in the 1980s and 1990s turned to crime in

attachmentto school is commonplace in the responsedecliningjob opportunities.All forms

biographies of delinquents and adult crimi- of criminaljustice supervision,includingincar-

nals (Sampson and Laub 1993, ch. 5; Hagan ceration, probationand parole, increased as a

and McCarthy 1997; Wolfgang, Figlio and consequence(Freeman1996, 26). Duster(1996)

Sellin 1972). High incarceration rates may similarly arguesthat the collapse of legitimate

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I54 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

employmentin poor urbanneighborhoodsdrew or are rejected by the deregulated low-wage

young black men into the illegal drug trade, labormarket"(Wacquant2001:83-84). Claims

steeplyincreasingtheirrisksof arrestandincar- of deepeningraceandclass inequalityin impris-

ceration.These analyses suggest that race and onment are also common among non-academ-

class inequalities in imprisonment deepened ic observers (e.g., Parenti2000; Miller 1996;

with rising inequalityin the 1980s and 1990s. Abramsky 2002). In sum, this account of the

Rising crime-especially drug-related prisonboom suggests our first hypothesis:That

crime-may have fed the prison boom, but race and class disparities in imprisonment

crime and imprisonmentdataindicate the pre- increasedthroughthe 1980s and 1990s.

eminent effect of crime control policy

(BlumsteinandBeck 1999;Boggess andBound IMPRISONMENTAND THE

1997). Like researchon crime, studies of crim- LIFECOURSE

inal justice policy suggest that race and class

divisions in the risks of imprisonment have In additionto increasingrace andclass inequal-

deepened. The argumentseems strongest for ities in incarceration,mass imprisonmentmay

the waron drugs.Intensifiedcriminalizationof mark a basic change in the characterof young

drug use swelled state and federalprison pop- adulthood among low-education black men.

ulationsby escalatingarrestrates,increasingthe From the life course perspective,prisonrepre-

risk of imprisonmentgiven arrest,and length- sents a significant re-orderingof the pathway

ening sentences for drug crimes through the throughadulthoodthatcan havelifelong effects.

1980s(Tonry1995;Mauer1999). Streetsweeps, Consequently, the prison boom-like other

undercover operations, and other aggressive large-scale social events-effects a historical-

policing efforts targetedpoor black neighbor- ly significanttransformationof the characterof

hoods wheredrugsweretradedin publicandthe adult life.

social networks of drug dealing were easily

penetrated by narcotics officers (Tonry PRISON AS A LIFE COURSE STAGE

1995:104-16). If poor black men were attract-

ed to illegal drug tradein response to the col- Life courseanalysisviews the passageto adult-

lapse of low-skill labor markets,the drug war hood as a sequence of well-orderedstages that

raisedthe risks thatthey would be caught,con- affect life trajectorieslong afterthe early tran-

victed and incarcerated. As Sampson and sitions are completed. In moderntimes, arriv-

Lauritsen(1997:360) observed,trends in drug ing at adultstatusinvolves moving from school

controlpolicy ensuredthat"bythe 1990s, race, to work, then to marriage, to establishing a

class, and drugsbecame intertwined." home and becoming a parent.Completingthis

The forceful prosecution of drug crime sequence without delay promotes stable

formed part of a broader, punitive, trend in employment,marriage,and otherpositive life

criminaljustice policy thatmandatedlong sen- outcomes. The process of becoming an adult

tences for violent and repeat offenders and thus influences success in fulfilling adultroles

increasingly returned parolees to prison and responsibilities.

(BlumsteinandBeck 1999).Collectivelytermed As an account of social integration, life

"the war on crime,"these changes in criminal course analysishas attractedthe interestof stu-

sentencing and supervisionreflected a historic dents of crime and deviance (see Uggen and

shift from a rehabilitativephilosophy of cor- Wakefield 2003 for a review). Criminologists

rections to crime preventionthroughthe inca- point to the normalizing effects of life course

pacitationof troublesomepopulations (Feeley transitions. Steady jobs and good marriages

andSimon 1992;Garland2001b). Like the drug offer criminal offenders sources of informal

war,the war on crimemay have disproportion- social controlandpro-socialnetworksthatcon-

ately affected disadvantaged minorities. tribute to criminal desistance (Sampson and

Wacquant(2000, 2001) arguesthat racial dis- Laub 1993; Hagan 1993; Uggen 2000).

parity and the penal system grew in tandem Persistent offending is more likely for those

with the economic decline of the ghetto. In this who fail to securethe markersof adultlife. The

analysis,the "recentracializationof U.S. impris- life courseapproachchallengesthe ideathatpat-

onment"is fuelled by a "supernumerary popu- terns of offending are determined chiefly by

lation of younger black men who either reject stablepropensitiesto crime,thatvarylittle over

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IN U.S. INCARCERATION155

RACEAND CLASSINEQUALITY

time, but greatlyacrossindividuals(Uggen and THEPRISON ANDTHE

BOOM

Wakefield 2003). OFADULTHOOD

TRANSFORMATION

Imprisonment significantly alters the life This account of imprisonmentas a stage in the

course. In most cases, men enteringprisonwill life coursedescribesthe effects of incarceration

already be "off-time."Time in juvenile incar- for individuals. In the historic context of the

cerationandjail andweak connectionsto work prison boom, incarcerationmay collectively

and family divert many prison inmates from reshape adulthoodfor whole birth cohorts. In

the usualpath followed by young adults.Spells this way, the growth of America's prisons is

of imprisonment-thirty to forty months on similarto othersocial transformationsthatpre-

average-further delay entry into the conven- cipitatedmajor shifts in life trajectories.Such

tional adultroles of worker,spouse andparent. shifts are often associatedwith large-scalepro-

More commonly military service, not impris- grams of social improvementlike the estab-

onment, is identified as the key institutional lishment of public education, or cataclysmic

eventslike depressionor wartime.Forexample,

experiencethatredirectslife trajectories(Hogan

World War Two drew nearly all young able-

1981; Elder 1986; Xie 1992). Elder(1987:543)

bodied U.S. men into military service, influ-

describesmilitaryservice as a "legitimatetime-

out" that offered disadvantagedservicemen in encing life chances and the sequence of life

stages (Elder 1986; Sampsonand Laub 1996).

WorldWarTwoan escapefromfamilyhardship. After the war, many young disadvantagedand

Similarly,imprisonmentcan provide a chance low-educationmen enlisted, attractedby pro-

to re-evaluate life's direction (Sampson and grams like the G.I. Bill (Elder 1999). The

Laub 1993, 223; Edin, Nelson, and Paranal episodic characterof World War Two can be

2001). Typically,though,the effects of impris- contrastedwith the hundred-yearemergenceof

onmentare clearlynegative.Ex-prisonersearn mass public education.The expansionof pub-

lower wages and experience more unemploy- lic educationin the UnitedStatescontributedto

mentthansimilarmen who havenot been incar- an increasinglyorderlyand compressedtransi-

cerated (Western, Kling and Weiman 2001 tion to adulthoodfor successive birth cohorts

review the literature).They are also less likely growing up through the twentieth century

to get marriedor cohabit with the mothers of (Modell, Furstenberg, and Hershberg 1976;

their children (Hagan and Dinovitzer 1999; Hogan 1981). The substantial,but ultimately

Western and McLanahan2000). By eroding stalled, convergence of African Americans on

the life patternsof whiteAmericais reflectedin

employmentandmarriageopportunities,incar- postwar increases in black high school gradu-

cerationmay also providea pathwayback into ation and college attendancerates (Allen and

crime (Sampson and Laub 1993; Warr1998). Jewell 1996).Both the expansionof publicedu-

The volatilityof adolescencemay thus last well cationandmilitaryservicein wartimeproduced

into midlife among men serving prison time. basic changes in the passage from adolescence

Finally,imprisonmentis an illegitimatetimeout to adulthood.

that confers an enduringstigma. Employersof Of course prison time is not chosen in the

low-skillworkersareextremelyreluctantto hire sameway as school attendanceor militaryserv-

men with criminalrecords(Holzer 1996;Pager ice. Men must commitcrimeto enterprison.As

2003). The stigma of a prison record also cre- Sutton (2000) observes, however,a variety of

ates legal barriersto skilled and licensed occu- institutions compete for jurisdiction over the

life course.Criteriaforentryintoprison,the mil-

pations, rights to welfare benefits, and voting

itary, or school are institutionally variable.

rights (Office of the PardonAttorney 1996;

Hirschet al. 2002; Uggen andManza2002). In DuringWorldWarTwo,the scale of theU.S.war

effort ensuredthat all able-bodiedyoung men

short,going to prisonis a turningpointin which werepotentialservicemen,andmost weredraft-

young crime-involvedmen acquirea new sta- ed. As the numberof college places expanded

tus involving diminished life chances and an duringthe 1960s and 1970s,youngmenbecame

attenuatedform of citizenship.The life course potentialcollege studentsqualifyingless on the

significance of imprisonment motivates our basis of social background,and more through

analysis of the evolving probabilityof prison academicachievement.If accountsof theprison

incarcerationover the life cycle. boom are correct,the prison emergedthrough

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

156 AMERICAN

SOCIOLOGICAL

REVIEW

the 1980s and 1990s as a major institutional Survey of Inmates of State and Federal

competitorto the military and the educational Correctional Facilities, Bonczar and Beck

system, at least for young black men with little (1997) estimatethat 9.0 percentof U.S. males

schooling. Much more than for older cohorts, will go to prison at some time in their lives.

the official criminalityof men born in the late Significant racialdisparityunderliesthis over-

1960s was determinedby race and class. all risk. The estimated lifetime risk of impris-

Historically,going to prisonwas a markerof onmentforblackmen is 28.5 percentcompared

extreme deviance, reserved for violent and to 4.4 percentfor white men. The risk of enter-

incorrigibleoffenders.Justas the thresholdfor ing prisonfor the first time is highestat ages 20

militaryservice was loweredduringWorldWar to 30, and declines significantly from age 35.

Two, the thresholdfor imprisonmentwas low- The BJS figuresprovidean importantstep in

eredby the wars on drugsand crime.The novel understandingthe risks of incarcerationover

normality of criminal justice sanction in the the life course, but the analysis can be extend-

lives of recentcohortsof disadvantagedminor- ed in at least two ways. First,the BJS age-spe-

ity men is now widely claimed. Freeman cific risks of incarcerationare not defined for

(1996:25) writes that "participationin crime any specific birthcohort;insteadthe incarcer-

and involvementin the criminaljustice system ation risks apply to a hypotheticalcohort that

has reachedsuchlevels as to becomepartof nor- shares the age-specific incarcerationrisks of

mal economic life for manyyoung men."Irwin all the differentcohortsrepresentedin the 1991

and Austin (1997:156) echo this observation: prison inmate surveys. This approach yields

"For many young males, especially African accurateresultsif the riskof incarcerationis sta-

AmericansandHispanics,the threatof going to ble over time. However,the incarcerationrate

prison or jail is no threat at all but ratheran and the percentageof men enteringprison for

expected or accepted part of life." Garland the first time grew substantiallybetween 1974

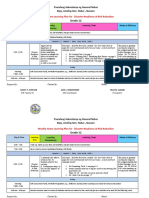

(2001lb:2), elaboratingthe idea of mass impris- and 1999 (Figure 1). The percentage impris-

onmentsimilarlyobservesthatfor "youngblack oned more thandoubledduringthis period.We

males in large urban centers ... imprisonment addressthis problemby combiningtime-series

... has come to be a regular predictable part of data on imprisonment(1964-1999) with mul-

experience." All these claims of pervasive tiple inmatessurveys (1974-1997). These data

imprisonmentsuggest a wholly new experience allow estimationof cumulativerisks of impris-

of adult life for recent cohorts of young disad- onmentto age 30-34 for five-yearbirthcohorts

vantaged men. Aggregate incarcerationrates born between 1945-49 and 1965-69. This

for the whole population are suggestive, but approachprovides a direct assessment of how

detailed empiricaltests are rare. the prison boom may have changed the life

The widely claimed significance of mass course of young men.

imprisonment in the lives of young African Second, like virtually all work in the field,

Americanmen suggeststwo furtherhypotheses. cumulativeriskshavenot been estimatedfor dif-

First,we expectthatimprisonmentby the 1990s ferent socio-economic groups. Motivated by

became a modal life event for young blackmen claims that the prison boom disproportionate-

with low levels of education. Second, we also ly affected the economically disadvantaged,as

expect that by the 1990s the experience of well as AfricanAmericans, we study how the

imprisonmentamong African American men risks of imprisonmentdiffer across levels of

would have rivaledin frequencymore familiar education.1

life stages such as militaryservice and college While our data sources and specific tech-

completion. niques differ, we follow Bonczar and Beck

(1997) in using life table methods. These

CALCULATINGTHE CUMULATIVE

RISK OF IMPRISONMENT

1 At leasttwo otherstudiesestimatecumulative

A life course analysis of the risks of imprison- risksof arrest,ratherthanimprisonment(Blumstein

ment was reportedby BonczarandBeck (1997) andGraddy1983;Tillman1987).Neitherof these

for the Bureauof JusticeStatistics(BJS). Using studiescomparerisks of arrestby class or across

life table methods and data from the 1991 cohorts.

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACEANDCLASSINEQUALITY

IN U.S. INCARCERATIONi57

(a) White Men

C,4

ci

C~CD

a a,Cc

? r: 00 8

'0

.1.L

aao

<C

1970 1980 1990 2000

Year

(a) BlackMen

CCo

CI

/.- r-..

Q C

c

aCN ",--

1970 1980 1990 2000

Year

Figure 1. Percentageof MenAdmittedto Prisonforthe FirstTime(solid line) andIncarcerated

(brokenline),

BlacksandWhites,Aged 18 to 34, 1974to 1999

methods are used to summarizethe mortality LIFE TABLECALCULATIONS

experiences of a cohort or in a particularperi-

od. The cumulativerisk of death, for example, Calculationsfor the cumulativerisk of impris-

can be calculatedby exposing a populationto onmentrequireage-specific first-incarceration

a set of age-specific mortalityrates. Life table andmortalityrates.The age-specificfirst-incar-

methodscan be appliedto otherrisks including ceration rate, is the number of people,

the riskof incarceration. Ourestimatesarebased aged x to x + nMx,

n, entering prison for the first

on multiple-decrementmethodsin which there time, divided by the numberof people of that

are severalindependentmodes of exit fromthe age in thepopulationat risk.Estimatingage-spe-

life table. The analysis allows two competing cific risks of first incarcerationrequires:(1)

risks: the risk of going to prison and the risk of the numberof people in age group x to x + n

death. annually admittedto prison for the first time,

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

158 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

.Fx, (2) the sum total of survivinginmates and risk-the number of first-time prison admis-

ex-inmates in that age group admittedin earli- sions for a cohort in age group x to x + n-is

er years, Sx,,and(3) a populationcountof those not directly observedbut can be estimatedby:

in the age group, Cx.These quantitiesare used

to calculatethe age-specific risks of first incar- = (Pt)(,kx)

nFx (6)

cerationin a given year: where Pt is the size of the prisonpopulationin

year t corresponding to the age group and

nMI=(nFx)/(,Cx - nSx) (1)

cohort,andnkxis the fractionof first admissions

Age-specific mortality rates, nMD, are taken in the penalpopulationthatenteredprisonin the

frompublishedmortalitytables.The combined past year.The proportion kxis estimatedusing

risk of exit fromthe table,nMx,is the sum of the Surveys of Inmates of State and Federal

risk of first incarcerationand the risk of mor- CorrectionalFacilities.The surveys have been

tality. conducted approximately every five years

between 1974 and 1997. Inter-surveyyearswere

nMx= nMxI+ nAMx (2)

interpolatedto provide annual estimates. (All

The probabilityof incarceration,nqI,between data sources are describedin the appendix.)

ages x and x+n is estimated from the age- Because estimates of the proportionof first

specific risk: admissions are based on survey data recorded

= (3)

at a single point in time, inmates incarcerated

nqx [(n)nMI]/[1+ .5(n)nMx] less thana yearareunder-counted.Information

(e.g., Namboodiri and Suchindran 1987:25). aboutbrief staysis incorporatedwith datafrom

This calculationassumesthatnew incarcerations the National Corrections Reporting Program

and deaths are distributedevenly over the age

(NCRP) (Bonczarand Beck 1997). NCRP data

interval and thus the average incarceration are used to calculatean adjustmentfactor,nPx,

occurs halfway throughthe interval. which is a functionof the fractionof briefprison

The probabilities of incarcerationare then

stays estimated to have been missed by the

used to calculatethe numberof incarcerations inmate surveys. The final estimate of first

occurringin the population.Assuming an ini- admissions in a given year is then:

tial populationof men exposed to the age-spe-

cific incarceration rates, lo = 100,000, the nFx = (nFx)(nPx). (7)

numberincarceratedduringthe first intervalis correctional data are needed to calculate

Only

equal to the numberat risk, lo, times the prob- the numberof first admissions but data on the

ability of incarceration,nqI.Subtractingthose non-institutionalpopulation must be used to

who were incarceratedor died, nd, gives the estimatethe riskof imprisonmentamongthose

numberof people alive and not yet incarcerat-

who have neverbeen incarcerated.The proba-

ed at the beginning of the next age interval,

Forthe five-yearage intervalswe use below, bility of first incarcerationis the countof first-

lx+n. time prison admissions divided by the

the number incarceratedin each subsequent

intervalcan then be calculated: populationat risk.Estimatingthe populationat

risk requires adjusting census data to take

accountof all priorfirst admissionsof the cohort

nd= (,qx)(lx),x = 15, 20, 25,

and the mortality and additional educational

and 30; n = 5. attainment of those previously admitted to

The cumulativerisk of incarcerationfrom age prison.

15-19 to 30-34 is the sum of incarcerations The age-specific risk of enteringprison for

over the initial population, the first time estimatedby

CumulativeRisk = (5) - (8)

.,dI/lo. ,M= (,Fx)/(nCx ,Sx)

where,

ESTIMATINGTHE PARAMETERS (9)

OF THE LIFE TABLE nSx:

and the weight, Frx)(wx)

gives the proportionof the

Fora specific race-educationsubgroup,the crit- cohortsurviving ,w,

fromthe beginningof yeart to

ical quantity for calculating the cumulative age x to x + n. In ouranalysesthe survivingfrac-

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACEAND CLASSINEQUALITY

IN U.S. INCARCERATIONi59

tion of a cohort is calculatedfrom age 15-19, unchanging.Neither assumption substantially

the firstintervalof exposureto the riskof prison affects our results because mortalityrates are

incarceration.Populationcounts,nC, aretaken low comparedto imprisonmentrates for men

from census enumerations and projections underage 35. Thus, a wide variety of mortali-

reportedin the StatisticalAbstractsof the United ty assumptions yield substantively identical

States (1974-1999). Mortalitydatato formthe conclusionsabouttherisksof imprisonment.For

survival rates are taken from life tables pub- example, the poor health of prisonersand their

lished in VitalStatisticsfor the UnitedStatesby exposureto violence likely increasesmortality

the National Centerfor Health Statistics. risk compared to men who have not been to

Cumulativerisks of imprisonmentare esti-

prison. We conducted a sensitivity analysis in

mated for three levels of education: (1) less which the mortality rate of men who have

than high school graduation,(2) high school entered prison was set to twice that for those

graduationor equivalency,and (3) at least some who had never been to prison; under this

college. Table1 reportsthe distributionof black assumptionthe results are essentially identical

and white men by education for cohorts born

to those reportedbelow.

1945-49 and 1965-69. By age 30 to 34, the

Althoughwe combinea wide varietyof data

three-categorycode roughly divides the black to estimate the cumulativerisks, our key data

andwhitemale populationintothe lower15 per-

source is the Survey of Inmates of State and

cent, the next 35 percent,andthe top 50 percent Federal Correctional Facilities, 1974-1997.

of the education distribution. Census data

Descriptive statistics from the surveys show

(1970-1990) are used to estimate population that the state prison populationbecame more

counts at each level of education.To adjustfor

differentialmortalityby educationwe use fig- educatedbetween1974 and 1997, increasingthe

ures from the National LongitudinalMortality numberof high school graduatesfrom38 to 60

Studywhich reportsmortalityby educationfor percent(Table2). The percentageof whites in

black and white men. These figures areused to prisonalso declined,due largelyto the increas-

calculatemultipliersfor each age-racegroupto ing shareof Hispanic men in state prison.

approximateeducation-specificmortalityrates. Instead of using life table methods, an indi-

Finally the surviving fraction of inmates is vidual'scumulativerisk of imprisonmentcould

adjusted to account for additional education be observed directly in a panel study in which

attainedafteradmissionto prison.The National a respondent'simprisonmentstatuswas updat-

LongitudinalSurveyofYouth(NLSY) was used ed at regularly-scheduledintervals.The NLSY

to estimatethe proportionof inmateswho go on approximatesthis design,althoughincarceration

graduatefrom high school or attendcollege in status is only recorded at the time of survey

each subsequentage interval. interview and data are availablefor a relative-

We assumethatmortalityratesfor men going ly small cohort born between 1957 and 1964.

to prison are the same as those for non-prison- NLSY figures are comparedto our estimates

ers and educationalinequality in mortality is below.

Table 1. Percentageof Non-HispanicMenat ThreeLevels of EducationalAttainment,Born 1945-1949 and

1965-1969, in 1979and 1999

WhiteMen (%) BlackMen (%)

Born 1945-1949 in 1979

Less thanhigh school 12.3 27.3

High school or equivalent 32.9 38.2

Some college 54.8 34.5

Born 1965-1969 in 1999

Less thanhigh school 7.5 14.2

High school or equivalent 33.4 43.0

Some college 59.1 42.8

Note: Cell entriesadjustforthe incarcerated

population,addingprisonandjail inmatesto the countsat eachlevel

of education.Datafromthe CurrentPopulationSurvey.

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i6o AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

Table2. Meansof DemographicandAdmissionVariablesfromStateandFederalSurveysof Correctional

Facilities,MaleInmates,1974-1997

State Federal

1974 1979 1986 1991 1997 1991 1997

FirstAdmissions(%) 43 62 58 62 63 71 70

Age (years) 30 29 31 32 33 37 37

Education

High school dropout(%) 62 51 52 42 40 24 26

High school/GED(%) 27 35 33 46 49 48 50

Some college 11 14 16 12 11 28 24

Race or Ethnicity

White(%) 45 42 40 35 33 39 30

Black(%) 47 47 45 46 46 29 38

Hispanic(%) 6 10 13 17 17 28 27

Samplesize 8741 9142 11397 11157 11349 4989 3176

RESULTS Table4 reportscumulativerisks for different

birth cohorts and education groups and com-

THEPREVALENCE

OFIMPRISONMENT

pares these to the usual prison incarceration

The full table for non-Hispanicblack andwhite rates.Incarcerationratesarehighly stratifiedby

men, born 1945-49 and 1965-69, illustrates educationand race. High school dropoutsare 3

the life table calculations(Table3). The risk of to 4 times more likely to be in prisonthanthose

first-time imprisonmentis patternedby age, with 12 years of schooling. Blacks, on aver-

cohort, and race. In contrast to crime where age, are about8 times more likely to be in state

or federalprison thanwhites. By the end of the

offending peaks in the late teens, the risk of

first-timeimprisonmentincreaseswith age and 1990s, 21 percent of young black poorly-edu-

catedmen were in state or federalprison com-

peaks for men in theirlate twenties.Not just an

event confined to late adolescence and young paredto an imprisonmentrateof 2.9 percentfor

adulthood,men in their early thirtiesremainat young white male dropouts.

The lowerpanels of Table4 show the cumu-

high risk of acquiringa prison record.The life lativerisks of imprisonment.Ourestimatesare

table also clearly indicates cohort differences.

Between ages 25 and 29, black men without broadly consistent with those from the BJS

(Bonczar and Beck 1997) and the NLSY. The

felony recordshad almost a 10 percentchance NLSY figures and those for the 1965-1969

of imprisonmentby the end of the 1990s (Table cohortof whitemen arein very close agreement.

3, column 3). This imprisonment risk is 2.5 Our estimates for black men, particularly

times higherthanthatfor blackmen at the same

dropouts, are higher than the NLSY figures,

age born twenty years earlier.The probability but lowerthanthose calculatedby the BJS.This

of imprisonmentfor white men was only one-

discrepancybetween data sources may be due

fifth as large. High age-specific risks among to under-countingof imprisonmentin theNLSY

recent birth cohorts of black men sum to large

(prison spells between survey interviews are

cumulativerisks. Black men born 1945-1949 not recorded),and surveynon-response.

had a 10.6 percent chance of spendingtime in Like incarcerationrates,the cumulativerisks

state or federal prison by their early thirties. of imprisonmentfall with increasingeducation.

This cumulativeriskhadclimbedto over20 per- The cumulativerisk of imprisonmentis 3 to 4

cent for black men born 1965-69. The cumu- times higher for high school dropoutsthan for

lative risk of imprisonmentgrew slightly faster high school graduates.About 1 out of 9 white

for white men. Among white men born male high school dropouts, born in the late

1965-1969, nearly3 percenthad been to prison 1960s, would serve prison time before age 35

by 1999, comparedto 1.4 percent born in the comparedto 1 out of 25 high school graduates.

older cohort (Table3, column 7). The cumulativerisk of incarcerationis about5

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACE

ANDCLASS INU.S.INCARCERATION

INEQUALITY i6i

Table3. Life Tablesfor CumulativeRisks of PrisonIncarceration

andMortalityforNon-HispanicMen Born

1945-49 and 1965-69

Age (years) nMI n91 ndn

nix

N CumulativeRisk

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

WhiteMen

Born 1945-1949

15-19 .0006 .0032 100000 318.5 318.5 .32

20-24 .0008 .0040 99444 393.4 712.0 .71

25-29 .0008 .0040 98768 396.3 1108.3 1.11

30-34 .0006 .0030 97429 289.0 1397.3 1.40

Born 1965-1969

15-19 .0008 .0039 100000 394.6 394.6 .39

20-24 .0007 .0033 99392 332.5 727.1 .73

25-29 .0024 .0118 98847 1163.2 1890.4 1.89

30-34 .0021 .0105 96817 1018.2 2908.6 2.91

BlackMen

Born 1945-1949

15-19 .0040 .0197 100000 1972.9 1972.9 1.97

20-24 .0064 .0313 97747 3056.8 5029.7 5.03

25-29 .0078 .0379 94291 3569.1 8598.8 8.60

30-34 .0045 .0222 88504 1962.6 10561.4 10.56

Born 1965-1969

15-19 .0042 .0206 100000 2064.4 2064.4 2.06

20-24 .0084 .0409 97742 3997.3 6061.7 6.06

25-29 .0205 .0964 93448 9006.6 15068.3 15.07

30-34 .0137 .0657 82720 5436.6 20504.9 20.50

Note: Cumulativerisksarefor incarcerations (in the presenceof mortality).

= age-specificincarcerationrate

nM,= of incarceration in the interval

nqx probability

= numberat risk(adjustedformortality)

nix

in

ndx= numberof incarcerations the interval

N = cumulativenumberof incarcerations

times higherfor black men. Incredibly,a black 1970s. If the selectivityof educationwere influ-

male dropout,born 1965-69, had nearly a 60 encingimprisonmentriskswe wouldalso expect

percentchance of serving time in prisonby the increased imprisonment among college-edu-

end of the 1990s. At the close of the decade, catedblacks,as college educationbecamemore

prisontime hadindeedbecomemodalforyoung common. However, risks of imprisonment

black men who failed to graduate from high among college-educated black men slightly

school. The cumulativerisks of imprisonment declined, not increased. We can also guard

also increasedto a high level among men who againstthe effects of selectivityby considering

had completed only 12 years of schooling. all non-college men, whose shareof the black

Nearly 1 out of 5 black men with just 12 years and white male populationsremainedroughly

of schooling went to prison by their early thir- constantfor ourperiod of study.When figures

ties. for dropouts and high school graduates are

It might be challengedthat growing impris- pooled together,the risk of imprisonmentfor

onmentrisksamongblackdropoutsresultsfrom non-college black men aged 30-34 in 1999 is

increasingeducationalattainment.While more 30.2 percentcomparedto 12.0 percentin 1979.

than a quarterof all black men born 1945-49 Prisontime has only recentlybecome a com-

had not completed high school by 1979, the mon life event for black men. Virtuallyall the

percentageof high school dropoutshad fallen increase in the risk of imprisonmentfalls on

to 14 percentby 1999 (Table1).The high school those with just a high school education. For

dropoutsof the late 1990s may be less able and non-college blackmen reachingtheirthirtiesat

more crime-pronethanthe dropoutsof the late the end of the 1970s, only 1 in 8 would go to

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

162 AMERICAN

SOCIOLOGICAL

REVIEW

Table4. Imprisonment RateatAges 20 to 34, andCumulativeRiskof Imprisonment,

Death,or Imprisonment

by Ages 30 to 34 by EducationalAttainment,Non-HispanicMen

Less than High School/

All High School GED All Noncollege Some College

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

ImprisonmentRate(%)

WhiteMen

1979 .4 1.0 .4 .6 .1

1999 1.0 2.9 1.7 1.9 .2

BlackMen

1979 3.2 5.7 2.7 4.0 1.5

1999 8.5 21.0 9.4 12.7 1.7

CumulativeRisk of

Imprisonmentby Ages 30-34

WhiteMen

BJS 3.0 - -

NLSY 4.3 11.3 3.7 5.1 1.5

1979 1.4 4.0 1.0 2.1 .5

1999 2.9 11.2 3.6 5.3 .7

BlackMen

BJS 24.6 - -

NLSY 18.7 30.9 18.8 19.3 7.2

1979 10.5 17.1 6.5 12.0 5.9

1999 20.5 58.9 18.4 30.2 4.9

CumulativeRisk of Deathor

Imprisonmentby Ages 30-34

WhiteMen

1979 3.8 7.8 3.5 4.9 1.5

1999 5.0 14.0 5.5 7.7 1.7

BlackMen

1979 15.6 23.8 11.6 17.8 8.7

1999 23.8 61.8 21.9 33.9 7.4

Note:The Bureauof JusticeStatistics(BJS)figuresarereportedby BonczarandBeck (1997) usinga synthetic

cohortfromthe Surveyof Inmatesof StateandFederalCorrectionalFacilities(1991). TheNationalLongitudinal

Surveyof Youth(NLSY)figuresgive the percentageof respondentswho haveeverbeeninterviewedin a correc-

tionalfacilityby age 35 (whitesN = 2171, blacksN = 881). The NLSY cohortwas born1957-1964.The 1979

cohortis born 1945-1949;the 1999 cohortis born1965-1969.

prison, and just 1 in 16 among high school TRENDSIN RACEAND CLASSDISPARITIES

graduates.Although these risks are high com-

The changing risks of imprisonment across

paredto the generalpopulation,imprisonment

cohorts can be describedby a regressionthat

was experiencedby a relatively small fraction

of non-college blackmen bornjust afterWorld writes the age-specific risk of first imprison-

WarTwo. ment (y) as a function of age, education,and

The final panel of Table 4 adds mortality race. For age group i (measuredby a 4-point

risks to the risks of imprisonment.Again, non- scale, Ai, for 15-19 years, 20-24 years, 25-29

college black men born in the late 1960s expe- years,30-34 years),in educationgroupj (meas-

riencehigh risks.Estimatesshow thatone-third ured by Ej, a vector of dummy variables for

die or go to prison by their early thirties.The high school dropoutsand those with some col-

tablealso indicatesthatthe riskof imprisonment lege), racek (indicatedby a dummyvariablefor

is much higher than the risk of death, so the blacks, Bk,and birth cohort 1 (indicatedby the

resultsarenot significantlyalteredby the addi- vector of dummy variables, C1, for cohorts

tion of mortality. 1950-55 to 1965-69),

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACEAND CLASSINEQUALITY

IN U.S. INCARCERATION163

log = a + Ai + y'Ej + 8Bk+ by 73 percent for each five-year age category

yojkl A'Cl + in the oldest cohort, born 1945-49, the age

Eijkl. (10)

effect had grown to 160 percent by the late

The model is fitted with a least squaresregres-

1990s. Imprisonmentdisparitiesby education

sion. Thisbasicmodelis augmentedwith cohort

also changed significantly.Throughthe 1980s

interactionsto studywhetherrace andclass dif-

and 1990s, a large gap in imprisonmentrisks

ferences in imprisonmentincreasedover time.

Table 5 reports results for the interaction openedbetween the college-educatedandhigh

model. The main effects in column (1) show school graduates. While this gap was nearly

variation in the risk of imprisonmentfor the zero for men aged 30-34 in 1979, high school

oldest birthcohort,born 1945-49. The positive graduateswere aboutfourtimes more likely to

effect for age reflects the peak years of impris- go to prisonthanmen with college educationby

onmentrisk in the late twenties. The education the late 1990s. The differentialrisk of impris-

effects indicatethat, for the oldest cohort,men onmentbetweendropoutsandhigh schoolgrad-

who attendcollege havethe sameriskof impris- uatesremainedstable.Estimatesof raceeffects

onment as high school graduates, net of the show no significant change in the relativerisk

effects of age and race. High school dropouts, of black incarceration. In sum, the risks of

however, are about four times (e1.38= 3.97) imprisonmentgenerallyincreasedforall groups,

more likely to go to prison than high school at all ages; racial inequality in imprisonment

graduates.Thereis also strongevidenceof racial remainedstable, but educationalinequalityin

disparitiesin the risk of imprisonmentfor men imprisonmentincreased.

born 1945-49, as blackmen areabout5.4 times

more likely to go to prison thanwhite men. IMPRISONMENTCOMPAREDTO OTHER LIFE

The changing risks of imprisonment are STAGES

describedby columns (2) to (5) in Table5. The

cohort main effects increase in size, and 20 Finally,we compareimprisonmentto otherlife

years afterthe birthof the 1945-49 cohort,the experiences that mark the transitionto adult-

imprisonmentrisk has more than doubled, hood. We report levels of educationalattain-

e"76 ment, maritaland militaryservice historiesfor

- 2.1. The age-imprisonment gradient also

became steeper.While incarcerationrisksgrew all and non-college men, using data from the

Table5. Regressionof Log Risk of PrisonIncarceration,

Non-HispanicBlack andWhiteMen, Born 1945-1969

CohortInteractions

MainEffects 1950-1954 1955-1959 1960-1964 1965-1969

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Intercept -.73** .16 .22 .59* .76**

(4.50) (.69) (.96) (2.59) (3.34)

Age .55** .11 .19 .41** .41**

(7.55) (1.03) (1.85) (4.04 (4.06)

Less thanHigh School 1.38** -.06 .14 .10 .12

(6.98) (.22) (.51) (.37) (.43)

SomeCollege -.03 -.17 -.41 -1.48** -1.42**

(.14) (.61) (1.45) (5.29) (5.08)

Black 1.69** -.04 -. 11 -.36 -.26

(10.46) (.16) (.48) (1.59) (1.13)

Note:The t statisticsappearin parentheses.Age is codedin five-yearcategories,ages 15-19 = -1.5, 20-24 = -.5,

25-29 = .5, 30-34 = 1.5. Coefficientsforthe interceptin columns(2)-(5) arecohortmaineffects.

R2= .95, N = 120

*p < .05; **p < .01

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

164 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

2000 census. To make the incarcerationrisks ties. Among black male high school dropouts,

comparableto censusstatistics,ourestimatesare the risk of imprisonmenthad increasedto 60

adjusted to describe the percentage of men, percent,establishingincarcerationas a normal

born 1965-69, who have everbeen imprisoned stopping point on the route to midlife.

and who survivedto 1999. Underscoringthe historicnovelty of the prison

The risks of each life event varies with race, boom, these risks of imprisonmentare about

but racial differences in imprisonmentgreatly threetimes higherthan20 years earlier.Second,

overshadows any other inequality (Table 6). race and class disparitiesin imprisonmentare

Among all men, whites in theirearlythirtiesare large and historically variable. In contrast to

more than twice as likely to hold a bachelor's claims that racial disparityhas grown,we find

degreethanblacks.Blacks areabout50 percent a pattern of stability in which incarceration

more likely to have served in the military. ratesand cumulativerisks of incarcerationare,

However, black men are about 7 times more on average,6 to 8 times higher for young black

likely to have a prison record. Indeed, recent men comparedto young whites. Class inequal-

birth cohorts of black men are more likely to ity increased, however, as a large gap in the

haveprisonrecords(22.4 percent)thanmilitary prevalence of imprisonmentopened between

records (17.4 percent) or bachelor's degrees college-educated and non-college men in the

(12.5 percent).The shareof the populationwith 1980s and the 1990s. Indeed,the lifetime risks

prison records is particularlystriking among of imprisonmentroughlydoubledfrom 1979 to

non-college men. Whereas few non-college 1999, but nearly all of this increasedrisk was

white men haveprisonrecords,nearlya thirdof experienced by those with just a high school

black men with less than a college education education. Third,imprisonmentnow rivals or

have been to prison.Non-college black men in overshadowsthe frequencyof militaryservice

theirearlythirtiesin 1999 weremorethantwice and college graduation for recent cohorts of

as likely to be ex-felons thanveterans.This evi- AfricanAmericanmen. For black men in their

dence suggests thatby 1999 imprisonmenthad mid-thirties at the end of the 1990s, prison

become a commonlife event forblackmen that recordswere nearlytwice as common as bach-

sharplydistinguishedtheir transitionto adult- elor'sdegrees. In this same birthcohortof non-

hood from that of white men. college black men, imprisonment was more

thantwice as common as military service.

In sum, exceptingthe hypothesisof increased

DISCUSSION

racial disparity, our main empirical expecta-

This analysisprovidesevidenceforthreeempir- tions aboutthe effectsof prisonboom on the life

ical claims. First, imprisonmenthas become a paths of young disadvantagedmen are strong-

commonlife eventforrecentbirthcohortsblack ly supported.Becauseracialdisparityin impris-

non-college men. In 1999, about30 percentof onmentis very high and risks of imprisonment

such men had gone to prisonby theirmid-thir- aregrowingparticularly quicklyamongnon-col-

Table6. Percentageof Non-HispanicBlackandWhiteMen,Born 1965-1969, ExperiencingLife Eventsand

Survivingto 1999

Life Event WhiteMen(%) BlackMen (%)

All Men

PrisonIncarceration 3.2 22.4

Bachelor'sDegree 31.6 12.5

MilitaryService 14.0 17.4

Marriage 72.5 59.3

NoncollegeMen

PrisonIncarceration 6.0 31.9

High SchoolDiploma/GED 73.5 64.4

MilitaryService 13.0 13.7

Marriage 72.8 55.9

Note:The incidenceof all life eventsexceptprisonincarceration

was calculatedfromthe 2000 Census.

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACEAND CLASS INEQUALITYIN U.S. INCARCERATION 165

lege men, the life path of non-college black APPENDIX. DATA SOURCESFOR LIFE

men through the criminal justice system is TABLE CALCULATIONS

divergingfromthe usualtrajectoryfollowedby

most young Americanadults. Survey of Inmates of State and Federal

CorrectionalFacilities,1974, 1979, 1986, 1991,

The high imprisonmentrisk of black non- 1997 (BJS 1990, 1997, 1994a, 1993; BJS and

college men is an intrinsicallyimportantsocial FederalBureauof Prisons2001; FederalBureau

fact aboutthe distinctivelife courseof the socio- of Prisons 1994b). Probabilitysamples of state

economicallydisadvantaged. Althoughthe mass and federalprisonpopulationsprovidinginfor-

imprisonmentof low-educationblackmen may mation about first admission status, race, age,

resultfromthe disparateimpactof criminaljus- and educationof prisoners.

tice policy, a rigorous test demands a similar Numberofsentencedprisoners underjurisdic-

study of patterns of criminal offending. tion of State and Federal correctionalauthori-

Increasedimprisonmentrisks among low-edu- ties (Maguire and Pastore 2001:507). These

cationmen maybe dueto increasedinvolvement yearend counts of the state and federal prison

in crime. If patternsof offending follow eco- population formed the base used to calculate

nomic trends,declining wages among non-col- age-specific first admissionrates.

Statistical Abstracts of the United States,

lege men overthe last 20 yearsmay underliethe 1964-1999. TheAbstractsprovidedannualpop-

growingriskof imprisonment.Researchershave ulation countsby age and race.

examinedthe consequencesof race differences Public Use Microdata 1% Sample of U.S.

in offending for official crime and imprison-

Population, 1970-2000 (Bureauof the Census

ment, but relatively little is known about edu- 1991, 1994, 1998; Ruggles and Sobek 2003).

cational differences in offending within race Census data were used to estimatepopulation

groups.To determinewhetherthe shiftingrisks counts of black men in differentbirth cohorts.

are due to policy or changingpatternsof crime, Census datawere interpolatedto obtainfigures

we thusneed to developestimatesof crimerates for inter-censusyears.

for differentrace-educationgroups. National Corrections Reporting Program

Mass imprisonment among recent birth (NCRP), 1983-1997 (BJS 2002). NCRP data

cohortsof non-collegeblackmen challengesus provides information on all admitted and

to includethe criminaljustice systemamongthe released prisonersin 32-38 states. These data

are used to calculate all admissions from new

key institutionalinfluences on Americansocial courtcommitmentsbetweenJuly 16 andJuly 15

inequality.The growthof military service dur- of the following year with sentences of at least

ing WorldWarTwo and the expansionof high- 1 year. We also identify all admissions during

er educationexemplifyprojectsof administered thatperiodthatwere dischargedbeforeJuly 15.

mobility in which the fate of disadvantaged Our adjustmentfactor, nPx, is the number of

groups was increasingly detached from their admissionsdividedby the numberof admissions

social background. Inequalities in imprison- minus the numberof discharges.

mentindicatethe reverseeffect, in whichthe life VitalStatisticsfor the UnitedStates (National

path of poor minorities was cleaved from the Center for Health Statistics 1964-1999). Vital

well-educated majority and disadvantagewas Statistics'annualage-specificmortalityratesfor

deepened,ratherthan diminished.More strik- blackandwhitemen formedbaselinesthatwere

ingly thanpatternsof militaryenlistment,mar- adjustedfor the three educationcategories.

US. National Longitudinal Mortality Study

riage, or college graduation, prison time

differentiatesthe young adulthoodof blackmen (Rogot, Sorlie, Johnson and Schmitt 1993).

These data were used calculate multipliersto

from the life course of most others. Convict

form mortalityrates at differentlevels of edu-

statusinheresnow, not in individualoffenders, cation.

but in entire demographiccategories. In this National LongitudinalSurveyofYouth(Center

context,the experienceof imprisonmentin the for Human Resource Research 2000). These

United States emerges as a key social division data were used to calculate the educational

marking a new pattern in the lives of recent mobility of men who hadbeen imprisoned.The

birth cohorts of black men. mobility datawere used to decrementpopula-

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

166 AMERICANSOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

tion counts of high school graduates and college Bourgois, Phillipe I. 1995. In Search of Respect:

attendees by estimates of those who had already Selling Crackin El Barrio. New York:Cambridge

experienced imprisonment at a lower level of UniversityPress.

education. Braithwaite,John.1979.Inequality,CrimeandPublic

Policy. London:Routledge.

Becky Pettitis anAssistantProfessorofSociology at Bridges,GeorgeS., RobertD. Crutchfield,andSusan

the Universityof Washington.Her researchfocuses Pitchford. 1994. "Analytical and Aggregation

on demographicprocesses and social inequality. Biases in Analyses of Imprisonment:Reconciling

Currentresearch examines the role of institutional Discrepancies in Studies of Racial Disparity."

Social Forces 31:166-182.

factors on labor marketopportunitiesand patterns

Bureau of the Census. 1994. Census of Population

of inequality.In addition to her workexaminingthe

role of theprison system in racial and class inequal- andHousing, 1980: Public Use MicrodataSample

ity in employmentand earnings in the she is (C SAMPLE):1-PercentSample.(Computerfile).

workingon a project studyingstructural U.S.,

and insti- Washington,DC: U.S. Dept. of Commerce,Bureau

tutional explanationsfor cross-countryvariation in of the Census (producer), 1985. Ann Arbor,MI:

women s labor force participation and gender Inter-universityConsortiumforPoliticalandSocial

Research (distributor),1994.

inequalityin earnings. Bureau of the Census. 1998. Census of Population

Bruce Westernis Professorof Sociologyat Princeton andHousing,1990: Public UseMicrodataSample:

University.His currentresearchexamines the caus- 1-Percent Sample. (Computerfile). 4th release.

es and consequences of the growth in theAmerican Washington,DC: U.S. Departmentof Commerce,

penal system, and patterns of inequality and dis- Bureauof the Census(producer),1995.AnnArbor,

criminationin low-wagelabor marketsin the United MI: Inter-universityConsortiumfor Political and

States. Social Research(distributor),1998.

Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). 1990. Surveyof

REFERENCES InmatesofState CorrectionalFacilitiesand Census

of State Adult Correctional Facilities, 1974.

Abramsky, Sasha. 2002. Hard Time Blues: How (Computerfile). Conductedby U.S. Department

Politics Built a Prison Nation. New York:Dunne of Commerce,Bureau of the Census. 3rd ICPSR

Books. ed. AnnArbor,MI:Inter-university Consortiumfor

Allen, WalterR. and Joseph O. Jewell. 1996. "The Political and Social Research (producerand dis-

Miseducationof Black America."Pp. 169-190 in tributor).

AnAmericanDilemmaRevisited:Race Relations Bureau of the Census. 1991. Census of Population

in a Changing World,edited by Obie Clayton,Jr. and Housing, 1970: Public Use Samples.

New York:Russell Sage Foundation. (Computer file). Washington, DC: U.S.

Blumstein, Alfred. 1982. "On Racial Departmentof Commerce,Bureauof the Census

Disproportionalityof the United States' Prison (producer),1971. Ann Arbor,MI: Inter-universi-

Populations." Journal of Criminal Law and ty Consortiumfor Political and Social Research

Criminology73:1259-81. (distributor).

Blumstein,Alfred. 1993. "RacialDisproportionality Bureau of Prisons. 1994b. Survey of Inmates of

in the U.S. PrisonPopulationRevisited."University Federal CorrectionalFacilities, 1991. (Computer

of ColoradoLaw Review 64:743-60. file). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Blumstein, Alfred and Allen J. Beck. 1999. Commerce, Bureau of the Census (producer),

"PopulationGrowthin U.S. Prisons,1980-1996." 1991. AnnArbor,MI:Inter-university Consortium

Pp. 17-62 in Crimeand Justice: Prisons, vol. 26, for Political and Social Research(distributor).

edited by Michael Tonry and Joan Petersilia. BJS. 1993. SurveyofInmates of State Correctional

Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press. Facilities, 1991. (Computerfile). Conductedby

Blumstein, Alfred and Elizabeth Graddy. 1981. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the

"Prevalence and Recidivism Index Arrests: A Census. ICPSR ed. Ann Arbor,MI: Inter-univer-

Feedback Model." Law and Society Review sity Consortiumfor Political and Social Research

16:265-290. (producerand distributor).

Boggess, ScottandJohnBound. 1997. "DidCriminal BJS. 1994a. Surveyoflnmates ofState Correctional

ActivityIncreaseDuringthe 1980s?Comparisons Facilities,1986. (Computerfile). Conductedby the

Across Data Sources."Social Science Quarterly U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the

78:725-739. Census. 2nd ICPSRed. Ann Arbor,MI: Inter-uni-

Bonczar,ThomasP.andAllen J.Beck. 1997. Lifetime versity Consortium for Political and Social

Likelihood of Going to State or Federal Prison. Research(producerand distributor),

Bureauof JusticeStatisticsBulletin,NCJ 160092. BJS. 1997. Surveyof Inmates of State Correctional

WashingtonDC: U.S. Departmentof Justice. Facilities,1979. (Computerfile). Conductedby the

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RACEAND CLASSINEQUALITY

IN U.S. INCARCERATION167

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the New Penology:Notes on the EmergingStrategyof

Census. 3rd ICPSRed. Ann Arbor,MI: Inter-uni- Corrections and Its Implications."Criminology

versity Consortium for Political and Social 30:449-474.

Research(producerand distributor). Freeman,RichardB. 1996. "WhyDo So ManyYoung

BJS and FederalBureauof Prisons. 2001. Surveyof AmericanMen Commit Crimes andWhat Might

Inmates in State and Federal Correctional We Do About It?" Journal of Economic

Facilities, 1997. (Computer file). Compiled by Perspectives 10:25-42.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Garland,David. 2001a. "Introduction: The Meaning

Census. ICPSR ed. Ann Arbor,MI: Inter-univer- of Mass Imprisonment." Pp. in 1-3 in Mass

sity Consortiumfor Political and Social Research Imprisonment:Social Causes and Consequences,

(producerand distributor). edited by David Garland. London, UK: Sage

BJS. 2002. NationalCorrectionsReportingProgram, Publications.

1983-1999. (Computerfile). Conductedby U.S. Garland,David.2001b. Cultureof Control:Crimeand

Departmentof Commerce,Bureauof the Census. Social Orderin ContemporarySociety. Chicago,

2nd ICPSR ed. AnnArbor, MI: Inter-university IL: Universityof Chicago Press.

Consortiumfor Politicaland Social Research(pro- Hagan, John. 1993. "The Social Embeddednessof

ducer and distributor). Crime and Unemployment." Criminology

CenterforHumanResourceResearch.2000. National 31:465-91.

Longitudinal Study of Youth, 1979-1998 Hagan,JohnandRonitDinovitzer.1999."Collateral

(Computer file). National Opinion Research Consequences of Imprisonment for Children,

Center,Universityof Chicago (producer).Center Communities,and Prisoners."Crimeand Justice

for HumanResources,Ohio StateUniversity(dis- 26:121-162.

tributor). Hagan, John, A.R. Gillis, and David Brownfield.

Chiricos,TheodoreG. andMiriamA. Delone. 1992. 1996. Criminological Controversies: A

"LaborSurplus and Punishment:A Review and MethodologicalPrimer. Boulder, CO: Westview

Assessment of Theory and Evidence." Social Press, 1996.

Problems 39:421-46. Hagan,JohnandBill McCarthy.1997.MeanStreets:

Cloward, Richard A. and Lloyd E. Ohlin. 1960. Youth Crime and Homelessness. New York:

Delinquency and Opportunity: A Theory of CambridgeUniversityPress, 1997.

Delinquent Gangs. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. Harrison, Paige M. and Jennifer Karberg. 2003.

Cohen, Albert. 1955. DelinquentBoys: The Culture "PrisonandJailInmatesat Midyear2002."Bureau

of the Gang. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. of Justice Statistics Bulletin. NCJ 198877.

Crutchfield,RobertD. and SusanR. Pitchford.1997. WashingtonDC: U.S. Departmentof Justice.

"Work and Crime: The Effects of Labor Hirsch,Amy E., SharonM. Dietrich, Rue Landau,

Stratification."Social Forces 76:93-118. Peter D. Schneider, Irv Ackelsberg, Judith

Duster,Troy.1996."Pattern,Purpose,andRace in the Bernstein-Baker,and Joseph Hohenstein. 2002.

Drug War:The Crisis of Credibilityin Criminal EveryDoor Closed:BarriersFacing Parentswith

Justice."Pp.260-287 in CrackinAmerica:Demon Criminal Records. Washington DC: Center for

Drugs and Social Justice, edited by Craig Law and Social Policy.

Reinarmanand Harry G. Levine. Berkeley, CA: Hogan, Dennis P. 1981. Transitions and Social

University of CaliforniaPress. Change: TheEarly Lives ofAmericanMen. New

Edin, Kathryn.2000. "Few Good Men: Why Poor York:Academic Press.

Mothers Don't Marry or Remarry."American Holzer, Harry J. 1996. WhatEmployers Want:Job

Prospect 11:26-31. Prospectsfor Less-EducatedWorkers.New York:

Edin, Kathryn, Timothy Nelson, and Rechelle Russell Sage Foundation.

Paranal.2001. "Fatherhoodand Incarcerationas Irwin,JohnJamesandJamesAustin. 1997.It'sAbout

PotentialTurningPointsin the CriminalCareersof Time: America 's Imprisonment Binge. Second

Unskilled Men."Paperpresentedat the Inequality Edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Summer Institute. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Jacobs,David andRonaldE. Helms. 1996. "Toward

University. a PoliticalModel of Incarceration:A Time-Series

Elder, Glen H. 1986. "MilitaryTimes and Turning Examinationof MultipleExplanationsfor Prison

Pointsin Men'sLives."DevelopmentalPsychology AdmissionRates."AmericanJournalofSociology

22:233-45. 102:323-57.

Elder,Glen H. 1987. "WarMobilizationandthe Life LaFree, Gary and Kriss A. Drass. "The Effect of

Course: A Cohort of World War II Veterans." Changes in Intraracial Income Inequality and

Sociological Forum2:449-72. Educational Attainment on Changes in Arrest

Elder, Glen H. 1999. Children of the Great Rates for AfricanAmericansand Whites, 1957 to

Depression. Boulder,CO: WestviewPress. 1990."AmericanSociological Review61:614-34.

Feeley,MalcolmM. andJonathanSimon. 1992. "The Langan, Patrick. 1985. "Racism on Trial: New

This content downloaded from 128.95.71.159 on Mon, 1 Apr 2013 22:46:45 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

Evidence to Explain the Racial Composition of ThroughLife.Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversity

Prison in the United States."Journal of Criminal Press.

Law and Criminology76:666-683. Sampson, Robert J. and Janet L. Lauritsen. 1997.

Maguire, Kathleen and Ann L. Pastore, eds. 2001. "Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Crime and

Sourcebookof CriminalJusticeStatistics(Online). CriminalJustice in the United States."Crimeand

Available: http://www.albany.edu/sourcebook/ Justice 21:311-374.

(Accessed June, 2002). Sampson, Robert J. and John H. Laub. 1996.

Mauer,Marc. 1999. Race to Incarcerate.New York: "SocioeconomicAchievementin the Life Course

The New Press. of Disadvantaged Men: Military Service as a

Merton,RobertK. 1968. Social Structureand Social Turning Point, Circa 1940-1965." American

Action. EnlargedEdition.New York:Free Press. Sociological Review 61:347-67.

Messner, Steven E, Lawrence E. Raffalovich, and Spitzer,Steven. 1975. "Towarda MarxianTheoryof

RichardMcMillan.2001. "EconomicDeprivation Deviance."Social Problems22:638-51.

and Changes in Homicide Arrest Rates for white StatisticalAbstractsofthe UnitedStates. 1964-1999.

and BlackYouths."Criminology39:591-613. Washington,DC: U.S. Bureauof the Census.

Miller, Jerome. 1996. Search and Destroy:African Steffensmeier,Darrell and Stephen Demuth. 2000.

AmericanMales in the CriminalJustice System. "Ethnicity and Sentencing Outcomes in U.S.

New York:CambridgeUniversity Press. FederalCourts:Who is PunishedMore Harshly?"

AmericanSociological Review 65:705-729.

Modell, John, FrankE Furstenberg,and Theodore

Hershberg.1976. "Social ChangeandTransitions Sutton, John. 2000. "Imprisonment and Social

to Adulthoodin HistoricalPerspective."Journalof Classificationin FiveCommon-LawDemocracies,

1955-1985." American Journal of Sociology

FamilyHistory 1:7-32.

106:350-96.

Morenoff, Jeffrey D., Ropbert J Sampson, and

Tillman, Robert. 1987. "The Size of the 'Criminal

Stephen W. Raudenbush.2001. "Neighborhood

Inequality, Collective Efficacy, and the Spatial Population': The Prevalence and Incidence of

Adult Arrest."Criminology25:561-79.

Dynamics of Urban Violence." Criminology

39:517-59. Tittle, CharlesR. 1994. "TheTheoreticalBases for

Inequalityin FormalSocial Control."Pp. 21-52 in

Namboodiri,Krishnanand C.M. Suchindran.1987.

Inequality,Crime, and Social Control,edited by

Life TableTechniquesand theirApplications.New

York:Academic Press. George S. Bridges and MarthaMyers. Boulder:

Westview.

National Center for Health Statistics. 1964-1999.

VitalStatistics of the UnitedStates. Washington, Tonry,Michael. 1995. Malign Neglect. New York:

OxfordUniversityPress.

DC: Departmentof Health and Human Services.

Office of the PardonAttorney.1996. CivilDisabilities Uggen, Christopher.2000. "GrowingOlder,Having

a Job, and Giving up Crime." American

of Convicted Felons: A State-by-State Survey. Sociological Review 65:529-546.

Washington,DC: U.S. Departmentof Justice. Uggen, Christopher and Jeff Manza. 2002.

Parenti,Christian.2000. LockdownAmerica:Police "DemocraticContraction?PoliticalConsequences

and Prisons in theAge of Crisis.New York:Verso of FelonDisenfranchisementin the UnitedStates."

Books. AmericanSociological Review 67:777-803.

Pager, Devah. 2003. "The Mark of a Criminal Uggen, Christopher and Sara Wakefield. 2003.

Record." American Journal of Sociology

"YoungAdults Reenteringthe Communityfrom

108:937-75. the Criminaljustice System: The Challenge of

Rogot, Eugene, Paul D. Sorlie, Norman J. Johnson, Becoming an Adult."In On YourOwn Withouta

andCatherineSchmitt.1993.A MortalityStudyof Net: The Transitionto Adulthoodfor Vulnerable

1.3 Millions Persons by Demographic,Social and Populations, edited by Wayne Osgood, Mike

Economic Factors: 1979-1985 Follow-Up. Foster,and Connie Flanagan.

Washington,DC: National Institutesof Health. Venkatesh, SudhirA. and Steven D. Levitt. 2000.

Ruggles, Steven and Matthew Sobek. 2003. "'Are We a Family or a Business?' History and

IntegratedPublic Use Microdata Series: Version Disjuncturein the UrbanAmericanStreetGang."

3.0. (Computerfile). Historical Census Projects, Theoryand Society 29:427-62.

Universityof Minnesota,Minneapolis(distributor), Wacquant, Loic. 2000. "The New 'Peculiar

2003. Available:http://www.ipums.org(Accessed Institution':On the Prison as SurrogateGhetto."

July,2003). TheoreticalCriminology4:377-89.

Rusche, Georg and Otto Kirchheimer. 1968. Wacquant,Loic. 2001. "Deadly Symbiosis: When

Punishment and Social Structure. New York: GhettoandPrisonMeet andMesh."Pp. 82-120 in