Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Altman and Bland 1999 - Statistics Notes How To Randomise

Uploaded by

Chris LeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Altman and Bland 1999 - Statistics Notes How To Randomise

Uploaded by

Chris LeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Education and debate

Much work still needs to be done to achieve this. To be 3 World Health Association. Global strategy for health for all by the year 2000.

Geneva: WHO, 1981. (WHO Health for All series No 3.)

useful in health policy at this level, all the targets need 4 Visschedijk J, Siméant S. Targets for health for all in the 21st century.

to be elaborated further and clear, practical statements World Health Stat Q 1998;51:56-67.

5 Van de Water HPA, van Herten LM. Never change a winning team? Review

must be made on their operation—especially the four of WHO’s new global policy: health for all in the 21st century. Leiden: TNO

targets on health policy and sustainable health systems. Prevention and Health, 1999.

The WHO should stimulate the discussion of these 6 World Health Organisation. Bridging the gaps. Geneva: WHO, 1995.

(World health report.)

important targets, but it should also be careful about 7 World Health Organisation. Fighting disease, fostering development. Geneva:

being too prescriptive about health systems since this WHO, 1996. (World health report.)

8 World Health Organisation. 1997: Conquering suffering, enriching humanity.

could be counterproductive. Geneva: WHO, 1997. (World health report.)

In addition, more attention should be given to the 9 Murray CJL, Lopez AD, eds. The global burden of disease. Boston: Harvard

usefulness of the targets in member states. One way of University Press, 1996.

10 United Nations. The world population prospects. New York: UN, 1998.

doing this is to rank the countries by target and to 11 United Nations Development Programme. Human development report

divide them into three groups. A specific level could be 1997. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

12 World Bank. Poverty reduction and the World Bank: progress and challenges in

set for each group. For example, for target 2, three such the 1990s. New York: World Bank, 1996.

groups could be distinguished as follows: 13 World Health Organisation. Third evaluation of health for all by the year

x Countries that have already achieved this target 14

2000. Geneva: WHO, 1999. (In press.)

Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research Relating to Future Intervention

x Countries for which the global target is achievable Options. Investing in health research and development. Geneva: WHO,1996.

and challenging (Document TDR/Gen/96.1.)

15 Taylor CE. Surveillance for equity in primary health care: policy implica-

x Countries that find the global target hard to achieve tions from international experience. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:1043-9.

and therefore “demotivating.” 16 Frerichs RR. Epidemiologic surveillance in developing countries. Annu

Rev Public Health 1991;12:257-80.

The first group needs stricter target levels, and the 17 World Health Organisation. Health for all renewal—building sustainable

third group less stringent ones. If a breakdown of this health systems: from policy to action. Report of meeting on 17-19 November 1997

kind is made for each target, some countries may be in Helsinki, Finland. Geneva: WHO, 1998.

18 World Health Organisation. EMC annual report 1996. Geneva: WHO:

classified in different groups for different targets. In this 1996.

way, the targets will provide an insight into the health 19 World Health Organisation. Physical status: the use and interpretation of

anthropometry of a WHO expert committee. Geneva: WHO, 1995. (WHO

status of the population and could be useful for policy technical report series No 834.)

makers in member states in encouraging action and 20 World Health Organisation. Global database on child growth and malnutri-

tion. Geneva: WHO, 1997.

allocating their resources. 21 World Health Organisation. Tobacco or health: a global status report. Geneva:

WHO, 1997.

We thank Dr J Visschedijk and Professor L J Gunning-Schepers 22 Erkens C. Cost-effectiveness of ‘short course chemotherapy’ in smear-negative

and other referees of this article for their helpful comments. tuberculosis. Utrecht: Netherlands School of Public Health, 1996.

Funding: This study was commissioned by Policy Action 23 Van de Water HPA, van Herten LM. Bull’s eye or Achilles’ heel: WHO’s Euro-

Coordination at the WHO and supported by an unrestricted pean health for all targets evaluated in the Netherlands. Leiden: Netherlands

educational grant from Merck & Co Inc, New Jersey, USA. Association for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) Prevention and

Health, 1996.

Competing interests: None declared.

24 Van de Water HPA, van Herten LM. Health policies on target? Review of

health target and priority setting in 18 European countries. Leiden:

1 World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA51.7. Health for all policy for the Netherlands Association for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) Preven-

twenty-first century. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1998. tion and Health, 1998.

2 World Health Association. Health for all in the 21st century. Geneva: WHO,

1998. (Accepted 4 May 1999)

Statistics notes

How to randomise

Douglas G Altman, J Martin Bland

We have explained why random allocation of place to start and also the direction in which to read ICRF Medical

Statistics Group,

treatments is a required feature of controlled trials.1 the table. The first 10 two digit numbers from a starting Centre for Statistics

Here we consider how to generate a random allocation place in column 2 are 85 80 62 36 96 56 17 17 23 87, in Medicine,

sequence. which translate into the sequence A B B B B B A A A Institute of Health

Sciences, Oxford

Almost always patients enter a trial in sequence A for the first 10 patients. We could instead have taken OX3 7LF

over a prolonged period. In the simplest procedure, each digit on its own, or numbers 00 to 49 for A and 50 Douglas G Altman,

simple randomisation, we determine each patient’s to 99 for B. There are countless possible strategies; it professor of statistics

in medicine

treatment at random independently with no con- makes no difference which is used.

straints. With equal allocation to two treatment groups We can easily generalise the approach. With three Department of

Public Health

this is equivalent to tossing a coin, although in practice groups we could use 01 to 33 for A, 34 to 66 for B, and Sciences, St

coins are rarely used. Instead we use computer gener- 67 to 99 for C (00 is ignored). We could allocate treat- George’s Hospital

Medical School,

ated random numbers. Suitable tables can be found in ments A and B in proportions 2 to 1 by using 01 to 66

London SW17 0RE

most statistics textbooks. The table shows an example2: for A and 67 to 99 for B. J Martin Bland,

the numbers can be considered as either random digits At any point in the sequence the numbers of professor of medical

from 0 to 9 or random integers from 0 to 99. patients allocated to each treatment will probably statistics

For equal allocation to two treatments we could differ, as in the above example. But sometimes we want Correspondence to:

Professor Altman.

take odd and even numbers to indicate treatments A to keep the numbers in each group very close at all

and B respectively. We must then choose an arbitrary times. Block randomisation (also called restricted BMJ 1999;319:703–4

BMJ VOLUME 319 11 SEPTEMBER 1999 www.bmj.com 703

Education and debate

compare two alternative treatments for breast cancer it

Excerpt from a table of random digits.2 The numbers used in the

might be important to stratify by menopausal status.

example are shown in bold

Separate lists of random numbers should then be con-

89 11 77 99 94 structed for premenopausal and postmenopausal

35 83 73 68 20

women. It is essential that stratified treatment

84 85 95 45 52

allocation is based on block randomisation within each

56 80 93 52 82

stratum rather than simple randomisation; otherwise

97 62 98 71 39

79 36 13 72 99

there will be no control of balance of treatments within

34 96 98 54 89

strata, so the object of stratification will be defeated.

69 56 88 97 43 Stratified randomisation can be extended to two or

09 17 78 78 02 more stratifying variables. For example, we might want

83 17 39 84 16 to extend the stratification in the breast cancer trial to

24 23 36 44 14 tumour size and number of positive nodes. A separate

39 87 30 20 41 randomisation list is needed for each combination of

75 18 53 77 83 categories. If we had two tumour size groups (say <4

33 93 39 24 81 and > 4cm) and three groups for node involvement (0,

22 52 01 86 71 1-4, > 4) as well as menopausal status, then we have

2 × 3 × 2 = 12 strata, which may exceed the limit of what

randomisation) is used for this purpose. For example, if is practical. Also with multiple strata some of the com-

we consider subjects in blocks of four at a time there binations of categories may be rare, so the intended

are only six ways in which two get A and two get B: treatment balance is not achieved.

1: A A B B 2: A B A B 3: A B B A 4: B B A A 5: B A In a multicentre study the patients within each cen-

B A 6: B A A B tre will need to be randomised separately unless there

We choose blocks at random to create the is a central coordinated randomising service. Thus

allocation sequence. Using the single digits of the pre- “centre” is a stratifying variable, and there may be other

vious random sequence and omitting numbers outside stratifying variables as well.

the range 1 to 6 we get 5 6 2 3 6 6 5 6 1 1. From these In small studies it is not practical to stratify on more

we can construct the block allocation sequence B A B than one or perhaps two variables, as the number of

A / B A A B / A B A B / A B B A / B A A B, and so on. strata can quickly approach the number of subjects.

The numbers in the two groups at any time can never When it is really important to achieve close similarity

differ by more than half the block length. Block size is between treatment groups for several variables

normally a multiple of the number of treatments. minimisation can be used—we discuss this method in a

Large blocks are best avoided as they control balance separate Statistics note.3

less well. It is possible to vary the block length, again at We have described the generation of a random

random, perhaps using a mixture of blocks of size 2, 4, sequence in some detail so that the principles are clear.

or 6. In practice, for many trials the process will be done by

While simple randomisation removes bias from the computer. Suitable software is available at http://

allocation procedure, it does not guarantee, for exam- www.sghms.ac.uk/phs/staff/jmb/jmb.htm.

ple, that the individuals in each group have a similar We shall also consider in a subsequent note the

age distribution. In small studies especially some practicalities of using a random sequence to allocate

chance imbalance will probably occur, which might treatments to patients.

complicate the interpretation of results. We can use

stratified randomisation to achieve approximate

1 Altman DG, Bland JM. Treatment allocation in controlled trials: why ran-

balance of important characteristics without sacrificing domise? BMJ 1999;318:1209.

the advantages of randomisation. The method is to 2 Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and

Hall, 1990: 540-4.

produce a separate block randomisation list for each 3 Treasure T, MacRae KD. Minimisation: the platinum standard for trials?

subgroup (stratum). For example, in a study to BMJ 1998;317:362-3.

One hundred years ago

Generalisation of salt infusions

The subcutaneous infusion of salt solution has proved of great been employed earlier. Several physicians have adopted Dr.

benefit in the treatment of collapse after severe operations. The Penrose’s method, and with the most gratifying results. The cases

practice, it may be said, developed from two sources: the new are reported fully in the Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital for

method of transfusion where water, instead of another person’s July last. The infusions of salt solution were administered just as

blood, is injected into the patient’s veins; and flushing of the after an operation. The salt solution, at a little above body

peritoneum, introduced by Lawson Tait. After flushing, much of temperature, is poured into a graduated bottle connected by a

the fluid left in the peritoneum is absorbed into the circulation, rubber tube with a needle. The pressure is regulated by elevating

greatly to the patient’s advantage. Dr. Clement Penrose has tried the bottle, or by means of a rubber bulb with valves; the needle is

the effect of subcutaneous salt infusions as a last extremity in introduced into the connective tissue under the breast or under

severe cases of pneumonia. He continues this treatment with the integuments of the thighs. There can be no doubt that

inhalations of oxygen. He has had experience of three cases, all subcutaneous saline infusions are increasing in popularity, and

considered hopeless, and succeeded in saving one. In the other little doubt that their use will be greatly extended in medicine as

two the prolongation of life and the relief of symptoms were so well as surgery.

marked that Dr. Penrose regretted that the treatment had not (BMJ 1899;ii:933)

704 BMJ VOLUME 319 11 SEPTEMBER 1999 www.bmj.com

You might also like

- How To Randomise BMJDocument3 pagesHow To Randomise BMJJu ChangNo ratings yet

- New Health Systems: Integrated Care and Health Inequalities ReductionFrom EverandNew Health Systems: Integrated Care and Health Inequalities ReductionNo ratings yet

- Mehu131 - U1 - T4 - Corticoesteroides en Meningitis TuberculosaDocument3 pagesMehu131 - U1 - T4 - Corticoesteroides en Meningitis TuberculosalizdanNo ratings yet

- Articulo HealthDocument9 pagesArticulo HealthAntonio MalacaraNo ratings yet

- Global Health for All: Knowledge, Politics, and PracticesFrom EverandGlobal Health for All: Knowledge, Politics, and PracticesNo ratings yet

- Bryant 2017Document20 pagesBryant 2017Jean M Huaman FiallegaNo ratings yet

- The Opioid Epidemic and the Therapeutic Community Model: An Essential GuideFrom EverandThe Opioid Epidemic and the Therapeutic Community Model: An Essential GuideJonathan D. AveryNo ratings yet

- WHPL Canon Kickbusch 2003 Contribution of The WHO To A New Public Health and Health Promotion Ajph.93.3.383Document6 pagesWHPL Canon Kickbusch 2003 Contribution of The WHO To A New Public Health and Health Promotion Ajph.93.3.383jaswanthlalam2010No ratings yet

- The Contribution of The World Health Organization To A New Public Health and Health PromotionDocument12 pagesThe Contribution of The World Health Organization To A New Public Health and Health PromotionLaura ZahariaNo ratings yet

- The Five Star DoctorDocument3 pagesThe Five Star DoctorTasya Laresa100% (1)

- The Measurement of Health and Health StatusDocument2 pagesThe Measurement of Health and Health StatusKes DimapilisNo ratings yet

- Neogi-2018-Patient Education and Engagement in Treat-To-targetDocument3 pagesNeogi-2018-Patient Education and Engagement in Treat-To-targetNash YoungNo ratings yet

- Health Systems Strengthening, Universal Health Coverage, Health Security and ResilienceDocument1 pageHealth Systems Strengthening, Universal Health Coverage, Health Security and ResilienceCharles ChalimbaNo ratings yet

- Sepulveda 2002 Paliative Care Who PerspectiveDocument6 pagesSepulveda 2002 Paliative Care Who PerspectiveDaniela MunteleNo ratings yet

- Who 2007-2017 PDFDocument152 pagesWho 2007-2017 PDFshindyayu widyaswaraNo ratings yet

- WHO HSE GCR 2015.5 Eng PDFDocument180 pagesWHO HSE GCR 2015.5 Eng PDFFull ColourNo ratings yet

- Reviewed Lecture International Health RMDC 1.18.52 PMDocument36 pagesReviewed Lecture International Health RMDC 1.18.52 PMSyed HussainNo ratings yet

- Comment: For Lancet On Universal Universal-Health-CoverageDocument2 pagesComment: For Lancet On Universal Universal-Health-Coverageapi-112905159No ratings yet

- Introduction: Positioning Universal Health Coverage in The Post-2015 Development AgendaDocument15 pagesIntroduction: Positioning Universal Health Coverage in The Post-2015 Development AgendaJihan SyafitriNo ratings yet

- WHO World ReportDocument204 pagesWHO World ReportAan NurwatiNo ratings yet

- Unit Ii. The Health Care Delivery SystemDocument8 pagesUnit Ii. The Health Care Delivery SystemShane PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Midtest For FKM Class A Read The Text WellDocument3 pagesMidtest For FKM Class A Read The Text WellDarsini Puji LNo ratings yet

- Years of The WHO Essential Medicines Lis20161105-14972-15gvha0-With-Cover-Page-V2Document8 pagesYears of The WHO Essential Medicines Lis20161105-14972-15gvha0-With-Cover-Page-V2Taufi HemyariNo ratings yet

- AFHS Global ConsultationDocument29 pagesAFHS Global Consultationapi-3749052No ratings yet

- Global Health and Nursing Group 2Document16 pagesGlobal Health and Nursing Group 2Kathleen Camile CenaNo ratings yet

- World Health Report 2004Document96 pagesWorld Health Report 2004agniesia_rakNo ratings yet

- How Can The Sustainable Development Goals Improve Global Health? Call For PapersDocument2 pagesHow Can The Sustainable Development Goals Improve Global Health? Call For PapersZelalem TilahunNo ratings yet

- CMH Working Paper SeriesDocument41 pagesCMH Working Paper SeriesPeter M. HeimlichNo ratings yet

- Gs Infant Feeding Text EngDocument36 pagesGs Infant Feeding Text Engreza yunusNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Delivery System Changes in the PhilippinesDocument9 pagesHealthcare Delivery System Changes in the PhilippinesKrystel Anne MilanNo ratings yet

- WO RLD Health Organization HistoryDocument9 pagesWO RLD Health Organization HistoryEmerina SoNo ratings yet

- World Health Report 2008Document148 pagesWorld Health Report 2008dancutrer2100% (2)

- Introduction To Essential DrugsDocument46 pagesIntroduction To Essential DrugsMrym NbNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Ncm104Document18 pagesReviewer Ncm104SONZA JENNEFERNo ratings yet

- The Continuing Evolution of Health Promotion - 2021Document3 pagesThe Continuing Evolution of Health Promotion - 2021nuno ferreiraNo ratings yet

- Community-Based Noncommunicable Disease Interventions: Lessons From Developed Countries For Developing OnesDocument8 pagesCommunity-Based Noncommunicable Disease Interventions: Lessons From Developed Countries For Developing Onessukainah al hadadNo ratings yet

- WHO - The World Health 2000Document215 pagesWHO - The World Health 2000esmoiponja100% (1)

- The World Health Report 2000Document27 pagesThe World Health Report 2000Perpustakaan stikesbpiNo ratings yet

- International HealthDocument110 pagesInternational HealthHiren patelNo ratings yet

- Nations For Mental Health: Final ReportDocument68 pagesNations For Mental Health: Final ReportEnchantia R. NightshadeNo ratings yet

- Key Data and Findings Maternal Health MedicinesDocument37 pagesKey Data and Findings Maternal Health MedicinesKabir AhmedNo ratings yet

- WHO Health Promotion Glossary: New TermsDocument6 pagesWHO Health Promotion Glossary: New TermsBrendan MaloneyNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 MUN Conference MessageDocument21 pagesCOVID-19 MUN Conference MessageAastha AroraNo ratings yet

- Olemberio Lesson Plan4Document5 pagesOlemberio Lesson Plan4Jayvee OlemberioNo ratings yet

- Preventing HIV in Young People: A Systematic Review of The Evidence From Developing CountriesDocument357 pagesPreventing HIV in Young People: A Systematic Review of The Evidence From Developing CountriesCrowdOutAIDSNo ratings yet

- Materi UTS Global HealthDocument141 pagesMateri UTS Global HealthNurul AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- WHO's Role in Combating COVID-19Document28 pagesWHO's Role in Combating COVID-19Priyanshi MehtaNo ratings yet

- Health and The Millennium Development Goals: School of Population HealthDocument15 pagesHealth and The Millennium Development Goals: School of Population HealthAtta BoamahNo ratings yet

- Origins of Primary Health Care and Selective Primary Health CareDocument16 pagesOrigins of Primary Health Care and Selective Primary Health CareMaria MahusayNo ratings yet

- Operationalizing One Health: Developing an Implementation RoadmapDocument24 pagesOperationalizing One Health: Developing an Implementation RoadmapsackNo ratings yet

- Who Global StrategyDocument37 pagesWho Global StrategyAdethya SimatupangNo ratings yet

- MDG Indicators HFS032Document16 pagesMDG Indicators HFS032teguhNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 10Document12 pagesMapeh 10mercadolorence20No ratings yet

- Strengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable developmentDocument3 pagesStrengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable developmentghoudzNo ratings yet

- Koplan2009 - Defincion de Salud GlobalDocument3 pagesKoplan2009 - Defincion de Salud GlobalIsa SuMe01No ratings yet

- UN Report Examines Link Between Nutrition, Diets and NCDsDocument12 pagesUN Report Examines Link Between Nutrition, Diets and NCDsVineet MariyappanNo ratings yet

- Global Health Issues and ConcernsDocument24 pagesGlobal Health Issues and ConcernsMa Eloiza Urbana100% (1)

- Urban Health in Developing CountriesDocument14 pagesUrban Health in Developing Countriesvictoriatatenda06No ratings yet

- 3B User-Manual CPAP-Auto-CPAP RESmart BMC V1.7 ENG-1Document35 pages3B User-Manual CPAP-Auto-CPAP RESmart BMC V1.7 ENG-1Ricardo Costa CaribéNo ratings yet

- Nursing Reflective Practice - An Empirical Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesNursing Reflective Practice - An Empirical Literature ReviewChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Reflections in LearningDocument17 pagesReflections in LearningChris LeeNo ratings yet

- The "Completely Randomised" and The "Randomised Block" Are The Only Experimental Designs Suitable For Widespread Use in Pre Clinical ResearchDocument5 pagesThe "Completely Randomised" and The "Randomised Block" Are The Only Experimental Designs Suitable For Widespread Use in Pre Clinical ResearchChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Reflection in and On Nursing Practices - How NursesDocument7 pagesReflection in and On Nursing Practices - How NursesChris LeeNo ratings yet

- 狗乾糧推薦名單2021Document5 pages狗乾糧推薦名單2021Chris LeeNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy of Tuberculosis in Hong KongDocument17 pagesChemotherapy of Tuberculosis in Hong KongChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Reflective Learning in Higher Education - A Comparative AnalysisDocument8 pagesReflective Learning in Higher Education - A Comparative AnalysisChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) Analysis: Normal ValuesDocument3 pagesArterial Blood Gas (ABG) Analysis: Normal ValuesNayem Hossain HemuNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia, Atelectasis & EffusionsDocument38 pagesPneumonia, Atelectasis & EffusionsChris LeeNo ratings yet

- RESmart - CPAP, Auto - User ManualDocument40 pagesRESmart - CPAP, Auto - User ManualChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Terms of The Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike-3.0 LicenseDocument109 pagesTerms of The Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike-3.0 LicenseChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Adult Cardiac Arrest Circular Algorithm: Monitor CPR QualityDocument1 pageAdult Cardiac Arrest Circular Algorithm: Monitor CPR QualityChris LeeNo ratings yet

- CT Scans of The Head: A Neurologist's PerspectiveDocument111 pagesCT Scans of The Head: A Neurologist's PerspectiveChris LeeNo ratings yet

- 12-Lead Ecgs and Electrical Axis: Fast & Easy Ecgs, 2Nd E - A Self-Paced Learning ProgramDocument66 pages12-Lead Ecgs and Electrical Axis: Fast & Easy Ecgs, 2Nd E - A Self-Paced Learning ProgramlalaNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia, Atelectasis & EffusionsDocument38 pagesPneumonia, Atelectasis & EffusionsChris LeeNo ratings yet

- 12-Lead Ecgs and Electrical Axis: Fast & Easy Ecgs, 2Nd E - A Self-Paced Learning ProgramDocument66 pages12-Lead Ecgs and Electrical Axis: Fast & Easy Ecgs, 2Nd E - A Self-Paced Learning ProgramlalaNo ratings yet

- Cir 0000000000000613 PDFDocument10 pagesCir 0000000000000613 PDFDeivy De Jesus Cordoba SerratoNo ratings yet

- How To Read A Head CTDocument90 pagesHow To Read A Head CTChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Thoracic Radiographic Anatomy: Einav Shochat MS4 Visiting Medical StudentDocument81 pagesThoracic Radiographic Anatomy: Einav Shochat MS4 Visiting Medical StudentChris LeeNo ratings yet

- CT Head and Ischemic Cva: What To Look For On The Early Scan??Document19 pagesCT Head and Ischemic Cva: What To Look For On The Early Scan??Chris LeeNo ratings yet

- Acute Stroke Management Resource:: Types of Stroke & Anatomy and Physiology of Acute StrokeDocument52 pagesAcute Stroke Management Resource:: Types of Stroke & Anatomy and Physiology of Acute StrokeChris LeeNo ratings yet

- CAPD - StaySafe Training Manual PDFDocument16 pagesCAPD - StaySafe Training Manual PDFChris LeeNo ratings yet

- 2 4 Plasma ProductsDocument3 pages2 4 Plasma Productsشريف عبد المنعمNo ratings yet

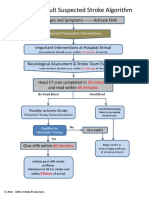

- ACLS Stroke Algorithm PDFDocument1 pageACLS Stroke Algorithm PDFChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Catheter Care Guidelines PDFDocument45 pagesCatheter Care Guidelines PDFJayakumar JNo ratings yet

- Nursing Tools Psychotherapy PDFDocument1 pageNursing Tools Psychotherapy PDFChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Bladder Irrigation CystoclysisDocument4 pagesBladder Irrigation Cystoclysisme meNo ratings yet

- Anorexia PaperDocument6 pagesAnorexia Paperapi-254016016No ratings yet

- Impact of Diabetic Ketoacidosis Management in The Medical Intensive Care Unit After Order Set ImplementationDocument6 pagesImpact of Diabetic Ketoacidosis Management in The Medical Intensive Care Unit After Order Set ImplementationFrancisco Sampedro0% (1)

- Elastic Bandage Applying PDFDocument4 pagesElastic Bandage Applying PDFDaniIrawanNo ratings yet

- Reproduction Pathology ReviewDocument9 pagesReproduction Pathology ReviewkishorechandraNo ratings yet

- BE FAST ED FormDocument1 pageBE FAST ED FormTHARHATA I JUHASANNo ratings yet

- Cebu Activity DesignDocument22 pagesCebu Activity DesignMariefer EsplagoNo ratings yet

- Frequency of Over Eruption in Unopposed Posterior TeethDocument7 pagesFrequency of Over Eruption in Unopposed Posterior TeethDaniel Lévano AlzamoraNo ratings yet

- Feeding Infants and ToddlersDocument6 pagesFeeding Infants and ToddlersNedum WilfredNo ratings yet

- First Aid KitDocument25 pagesFirst Aid Kitgo back to natureNo ratings yet

- Sleep Disorders in The ElderlyDocument50 pagesSleep Disorders in The ElderlykikimarioNo ratings yet

- Vertical Root Fractures in Endodontically Treated Teeth A Clinical SurveyDocument4 pagesVertical Root Fractures in Endodontically Treated Teeth A Clinical SurveyVimi GeorgeNo ratings yet

- ChemDocument15 pagesChemYaghvi VaishnavNo ratings yet

- WWTPD Lab Assign 3Document3 pagesWWTPD Lab Assign 3Zohaib BaigNo ratings yet

- Keep Your Eyes HealthyDocument20 pagesKeep Your Eyes HealthydrjperumalNo ratings yet

- Congestive Heart FailureDocument15 pagesCongestive Heart FailureChiraz Mwangi100% (1)

- FilgrastimDocument3 pagesFilgrastimapi-3797941No ratings yet

- Geriatric Assessment TomtomDocument4 pagesGeriatric Assessment TomtomMark Angelo Soliman AcupidoNo ratings yet

- Medication ErrorsDocument13 pagesMedication Errorsrozsheng100% (1)

- 2.D Ndera CaseDocument9 pages2.D Ndera CaseNsengimana Eric MaxigyNo ratings yet

- Knowledge DeficitDocument2 pagesKnowledge DeficitSahara Sahjz Macabangun67% (3)

- Bio 473 Reproductive Endocrinology Lab Compiled LabDocument10 pagesBio 473 Reproductive Endocrinology Lab Compiled Labapi-253602935No ratings yet

- Color Atlas of Emergency TraumaDocument314 pagesColor Atlas of Emergency TraumaIacob Razvan75% (8)

- Drug Therapy ProblemDocument19 pagesDrug Therapy ProblemAulia NorfiantikaNo ratings yet

- After 2 Hours of Nursing Intervention, The Mother Will Verbalized The Understanding of The Condition, Process, and TreatmentDocument3 pagesAfter 2 Hours of Nursing Intervention, The Mother Will Verbalized The Understanding of The Condition, Process, and TreatmentJelly Yanquiling DumlaoNo ratings yet

- Power Point ClabsiDocument11 pagesPower Point Clabsiapi-290870524No ratings yet

- Varcarolis: Essentials of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: Test Bank Chapter 10: Personality Disorders Multiple ChoiceDocument17 pagesVarcarolis: Essentials of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing: Test Bank Chapter 10: Personality Disorders Multiple Choiceyaneidys perezNo ratings yet

- Addiction Treatment Homework Planner Practiceplanners 5th Edition Ebook PDF VersionDocument62 pagesAddiction Treatment Homework Planner Practiceplanners 5th Edition Ebook PDF Versionjames.keeter43297% (39)

- NRS476.pdf Answer PDFDocument13 pagesNRS476.pdf Answer PDFsyabiellaNo ratings yet

- Social Case Study Report: I. Identifying InformationDocument4 pagesSocial Case Study Report: I. Identifying InformationLeoterio LacapNo ratings yet

- Torts: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideFrom EverandTorts: QuickStudy Laminated Reference GuideRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyFrom EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Dictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersFrom EverandDictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Legal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesFrom EverandLegal Writing in Plain English, Third Edition: A Text with ExercisesNo ratings yet

- Nolo's Encyclopedia of Everyday Law: Answers to Your Most Frequently Asked Legal QuestionsFrom EverandNolo's Encyclopedia of Everyday Law: Answers to Your Most Frequently Asked Legal QuestionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (18)

- Legal Writing in Plain English: A Text with ExercisesFrom EverandLegal Writing in Plain English: A Text with ExercisesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Employment Law: a Quickstudy Digital Law ReferenceFrom EverandEmployment Law: a Quickstudy Digital Law ReferenceRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Legal Forms for Starting & Running a Small Business: 65 Essential Agreements, Contracts, Leases & LettersFrom EverandLegal Forms for Starting & Running a Small Business: 65 Essential Agreements, Contracts, Leases & LettersNo ratings yet

- LLC or Corporation?: Choose the Right Form for Your BusinessFrom EverandLLC or Corporation?: Choose the Right Form for Your BusinessRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Nolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First HomeFrom EverandNolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First HomeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (43)

- Everybody's Guide to the Law: All The Legal Information You Need in One Comprehensive VolumeFrom EverandEverybody's Guide to the Law: All The Legal Information You Need in One Comprehensive VolumeNo ratings yet

- Nolo's Deposition Handbook: The Essential Guide for Anyone Facing or Conducting a DepositionFrom EverandNolo's Deposition Handbook: The Essential Guide for Anyone Facing or Conducting a DepositionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Student's Guide to Law School: What Counts, What Helps, and What MattersFrom EverandA Student's Guide to Law School: What Counts, What Helps, and What MattersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Legal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessFrom EverandLegal Guide for Starting & Running a Small BusinessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Form Your Own Limited Liability Company: Create An LLC in Any StateFrom EverandForm Your Own Limited Liability Company: Create An LLC in Any StateNo ratings yet

- Essential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsFrom EverandEssential Guide to Workplace Investigations, The: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & ProblemsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- So You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolFrom EverandSo You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolNo ratings yet

- Nolo's Essential Guide to Child Custody and SupportFrom EverandNolo's Essential Guide to Child Custody and SupportRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)