Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ketorolac As An Analgesic Agent For Infants and Children After Cardiac Surgery

Uploaded by

diogofc123Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ketorolac As An Analgesic Agent For Infants and Children After Cardiac Surgery

Uploaded by

diogofc123Copyright:

Available Formats

AACN Advanced Critical Care

Volume 25, Number 1, pp.23-30

© 2014 AACN

Ketorolac as an Analgesic Agent

for Infants and Children After

Cardiac Surgery

Safety Profile and Appropriate Patient Selection

Meredith K. Jalkut, RN, MSN, CRNP

ABSTRACT

Ketorolac has been used safely as an analge- sparing effect. The literature reflects that the

sic agent for children following cardiac sur- use of this medication is not well studied in

gery in selected populations. Controversy certain pediatric cardiac patients such as

exists among institutions about the risks neonates and those with single-ventricle

involved with this medication in this patient physiology, and the safety of this medication

group. This article reviews the current litera- in regards to these special populations is

ture regarding the safety of ketorolac for reviewed. In conclusion, ketorolac can be

postoperative pain management in children used in specific pediatric patients after car-

after cardiac surgery. Specifically, concerns diac surgery with minimal risk of bleeding or

about renal dysfunction and increased bleed- renal dysfunction with appropriate dosing

ing risk are addressed. Additionally, the arti- and duration of use.

cle details pharmacokinetics and potential Keywords: cardiac surgery, children, ketorolac,

benefits of ketorolac, such as its opioid- pain management

P ain management following cardiac sur-

gery is an important element of postoper-

ative management in infants and children. A

The most common pain management strat-

egy for pediatric patients who have undergone

cardiac surgery is a combination of opioids

large percentage of children who have cardiac and acetaminophen for analgesia and benzodi-

surgery are infants younger than 1 year.1 This azepines for agitation and anxiety.3 Continu-

population often experiences dramatic hemo- ous administrations of fentanyl and midazolam

dynamic changes after cardiac surgery, and are frequently used for patients who remain

achieving adequate pain management can be a intubated postoperatively.3 Intermittent mor-

challenge.2 Inadequate pain control for patients phine and rectal or intravenous (IV) acetami-

of any age following cardiac surgery can lead nophen are often used for patients who have a

to increased metabolic demand and oxygen natural airway until they are able to take

consumption, which can subsequently cause

inadequate cardiac output and decreased venti-

lation.2 In addition to limiting physiological Meredith K. Jalkut is Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Children’s

stress, appropriate pain management following Hospital of Philadelphia, 1519 S Clarion St, Philadelphia, PA

cardiac surgery allows patients to perform age- 19147 (meredith.jalkut@gmail.com).

appropriate tasks that aid in the recovery pro- The author declares no conflicts of interest.

cess (ie, eating, getting out of bed, walking).3 DOI: 10.1097/NCI.0000000000000002

23

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 23 06/01/14 4:40 PM

JA LK UT W W W.A ACNA DVA NCE D CRIT ICA LCA RE .COM

enteral nutrition, at which time they are started shown to provide analgesia in 50% of the

on enteral acetaminophen and oxycodone.3 population in adults, they recommended that

The use of dexmedetomidine is becoming a the drug be dosed every 4 to 6 hours.7 By con-

frequent practice for the periextubation and trast, in a different study, clearance of the drug

early postoperative periods.4 was found to be higher for neonates and young

Ketorolac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflamma- infants compared with reported clearance rates

tory drug (NSAID), is frequently used as an for older children and adults.8 Both studies

analgesic medication in both adult and pediat- were limited by small cohort size, and each

ric populations for postoperative pain manage- patient received only 1 dose of the drug with

ment.5 Use of this medication for children serial blood sampling for plasma concentra-

following heart surgery is controversial tion. In addition, exclusion criteria for each

because of concern for renal dysfunction, gas- cohort included cardiac, renal, hepatic, and

trointestinal (GI) bleeding, and surgical hematologic disease, prematurity, low birth

bleeding.3 The objective of this article is to weight, and use of aspirin. Further data are

review the pharmacokinetics of ketorolac, the needed on the clearance and pharmacokinetics

current literature on the safety profile of this of ketorolac in relation to neonates and infants,

medication, and the benefits seen with reduc- especially those with cardiac disease or follow-

tion in opioid use with concurrent use of ing cardiac surgery.

ketorolac. Review of the current literature will

help advanced practice nurses in selection of Renal Toxicity With Use of

pain medications for pediatric patients follow- Ketorolac

ing cardiac surgery. Renal toxicity has been reported as an adverse

side effect in the safety profile of ketorolac. As

Pharmacological Properties with other NSAIDs, the risk to the kidneys

of Ketorolac involves inhibition of prostaglandin-mediated

In the reviewed literature, ketorolac was dosed renal function. Prostaglandins serve to vasodi-

at 0.5 mg/kg administered intravenously (IV) late renal vessels; inhibition by an NSAID can

every 6 hours for less than 4 days; most reduce renal blood flow.9 Reduction in renal

patients received the drug for less than 48 hours. blood flow can be seen clinically with decreased

In only 1 study were patients given a loading urine output and elevated serum creatinine

dose of 1 mg/kg.6 Ketorolac produces analgesia level from baseline.9 The drug was first intro-

by acting as a nonselective inhibitor of the duced in Europe several decades ago with

cyclooxygenase enzyme that is implicated in higher dosing recommendation and duration

pain receptors. This drug is highly bound in of therapy.9 Many cases of severe adverse

the plasma and undergoes very little metabo- effects, including renal toxicity, GI bleeding,

lism before being excreted almost entirely by and surgical site bleeding, were reported in

the kidneys.7,8 Some literature hypothesizes adults. Since the time of these events, the man-

that infants have higher clearance of drug ufacturer has reduced the recommended dos-

because of their relatively high volume of body ing range and duration of therapy.9 Renal

water and lower plasma protein than adults.8 injury persists as a concern for patients who

Other authors7 have suggested that the receive this medication, despite multiple large

opposite is true based on overall lower renal studies of adults receiving this drug at current

clearance in infants. These opposing theories recommended dosing, which is 30 mg IV every

present a challenge for providers to make an 6 hours for up to 96 hours.9

informed decision about prescribing this medi- Children undergoing cardiac surgery may

cation to neonates and patients with abnormal have increased risk for renal injury for several

renal clearance. reasons. Children presenting for cardiac surgery

Two studies evaluated the pharmacokinetics may have compensated or uncompensated heart

of ketorolac on infants from the neonatal failure, which can lead to reduction in renal per-

period to 11 months of age. Cohen and fusion in the preoperative state.10 In addition, car-

colleagues7 concluded that the clearance rate of diopulmonary bypass surgery can be followed by

ketorolac after a single dose of 0.5 mg/kg IV a low cardiac output state during which renal

was similar to that of adults. The mean half- perfusion is decreased.1 Finally, patients fre-

life of the drug was 233 minutes. On the basis quently receive loop diuretics following cardiac

of a goal serum concentration of ketorolac surgery, which may predispose them to a prerenal

24

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 24 06/01/14 4:40 PM

VOL UME 2 5 • N U MBER 1 • JANUARY–M ARCH 2014 KE TOROLAC IN P OSTOP E RAT IVE CA RD IAC P E D IAT RICS

state.11 Some clinicians are reluctant to expose physiology, preoperative renal impairment

patients to an NSAID concurrently with a loop defined as serum creatinine level greater than

diuretic while renal function as measured by 0.6 mg/dL, or BUN level greater than 15 mg/

urine output and serum creatinine may be unpre- dL were excluded. Data analysis demonstrated

dictable.11 Providers are challenged to determine that these patients did not have statistically sig-

exactly which patients are at risk for renal dys- nificant change in renal function as measured

function with the use of ketorolac based on other by serum creatinine and BUN levels.

clinical issues.11 A retrospective study evaluated 248 children

To date, a few prospective studies and sev- between the ages of 5 months and 18 years who

eral retrospective studies have evaluated the received ketorolac following cardiac surgery.13

renal safety of ketorolac in children who have The authors of this study evaluated serum cre-

undergone cardiac surgery.6 One study included atinine level, BUN level, and urine output, in

a retrospective chart review of 62 pediatric addition to the use of furosemide. Patients who

patients who had received ketorolac for pain were included in this study were categorized as

control following cardiac surgery. All of the having low-risk cardiac surgery, such as repair

patients studied were younger than 6 months; of atrial septal defect and ventricular septal

11 (18%) were younger than 1 month. Surgical defect repairs or right ventricle to pulmonary

intervention ranged from arterial switch opera- artery conduit revisions, and were compared

tion to atrial septal defect closure. Eighty-three with patients of similar age and clinical condi-

percent of the patients underwent cardiopulmo- tion following the same cardiac surgeries who

nary bypass during the surgery. Serum creati- did not receive ketorolac. The authors found

nine level was compared with baseline after that patients who had received ketorolac com-

patients received ketorolac 0.5 mg/kg IV every pared with those who had not had no increase in

6 hours for 48 hours The group found that 16 serum creatinine or BUN level and no decreased

patients had a statistically significant increase in urine output. They also found that those patients

serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen who received ketorolac for pain management

(BUN) levels, including 2 of 11 neonates. The received on average less furosemide than patients

largest increase in creatinine level for any who did not receive ketorolac for reasons that

patient was 0.3 mg/dL. The peak serum creati- were unclear to the authors.13 Table 1 summa-

nine and BUN levels were still within the range rizes the current literature on risk of renal dys-

of normal for age for each patient, and the function with the use of ketorolac.

authors of this study did not think that eleva- The current literature demonstrates safety in

tion of this value after patients received the use of ketorolac in patients with biventricu-

ketorolac was clinically significant. All patients’ lar repairs and no preoperative renal dysfunc-

serum creatinine and BUN levels returned to tion, with minimal risk of postoperative renal

baseline, indicating that no long-term renal dysfunction or renal insufficiency as evidenced

injury occurred.6 Urine output and creatinine by serum creatinine levels and urine output. As

clearance were not evaluated in this study. The previously described, prospective randomized

authors do not comment on the concurrent use control studies are lacking. Studies including

of furosemide or other diuretics in these patients children with single-ventricle physiology and

but note that patients with a statistically signifi- neonates have small cohorts.6,14 The effects of

cant increase in creatinine also had a negative ketorolac on patients in high-risk categories,

fluid balance.6 such as those with single-ventricle physiology or

Similarly, other studies suggest that those with more complex cardiac surgeries requir-

ketorolac does not pose a risk to renal function ing longer bypass times, are not well-studied.

in young cardiac surgical patients. Another ret- Therefore, this medication can be recommended

rospective study also concluded that ketorolac only for nonneonates with biventricular physio-

does not cause a significant rise in serum cre- logy undergoing cardiac surgery.

atinine levels in infants younger than 6 months

with biventricular physiology.12 The authors Bleeding Risk With Use of

of this study completed a chart review of Ketorolac

19 patients who had received ketorolac As with all of the drugs in the NSAID class,

for postoperative pain management. These ketorolac is associated with a theoretical

patients were matched to control group by age. increased risk of bleeding caused by thrombox-

Infants with NSAID allergies, single-ventricle ane A2 inhibition. Thromboxane is a mediator

25

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 25 06/01/14 4:40 PM

JA LK UT W W W.A ACNA DVA NCE D CRIT ICA LCA RE .COM

Table 1: Summary of Literature Review of Renal Insufficiency With Use of Ketorolac

Patient Population/ Outcomes

Reference Study Design Measured Results Ketorolac Dosing

Dawkins et al12 Infants younger than BUN, serum No significant 0.5 mg/kg IV every

6 months, status creatinine increase in serum 6 h for average

postcardiac surgery, creatinine or BUN of 3.1 d

biventricular physiol- compared with

ogy/retrospective nonketorolac

chart review group

Inoue et al13 Infants and children Serum creatinine, No significant 0.5 mg/kg IV every

post low-risk cardiac BUN, urine increase in serum 6 h for average

surgery/retrospec- output creatinine and 36 h

tive chart review BUN or decrease

in urine output

compared with

nonketorolac

group

Moffett et al6 Infants younger than Serum creatinine, No significant Mean 0.44 mg/kg

6 mo postcardiac BUN increase in serum IV every 6 h

surgery/retrospec- creatinine or BUN

tive chart review compared with

nonketorolac con-

trol group

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; IV, intravenous.

of platelet aggregation that is altered with the chest tube drainage, wound bleeding as meas-

prostaglandin inhibition caused by all NSAIDs.9 ured by visual observation and dressings, and

In addition, ketorolac and other NSAIDs inhibit GI bleeding measured by emesis or output

prostaglandin-dependent suppression of gastric from a gastric decompression tube.14 Patients

acid, causing an increased risk of GI bleeding.9 were aged 2 days to 18 years, and all under-

Providers historically have been resistant to giv- went cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. The

ing this drug for pain management in postopera- authors excluded patients with history of

tive patients because of the risk of bleeding, both recent GI bleed, bleeding in the first 6 postop-

at the surgical site and in the GI tract. A study of erative hours requiring reoperation/explora-

healthy, adult volunteers showed that bleeding tion or blood product transfusion, cardiac

times were significantly prolonged compared transplantation, or delayed sternal closure.

with baseline after a dose of intramuscular The study included a total of 70 patients

ketorolac, but platelet aggregation was similar divided between the ketorolac and nonke-

after the dose compared with the baseline,15 torolac groups. The patients in the ketorolac

which may have a relevance to surgical site group received 0.5 mg/kg per dose every 6

bleeding postoperatively for patients receiving hours starting 12 hours after surgery for up to

ketorolac after cardiac surgery. 48 hours total. Patients in both groups had

This drug is well-studied in the adult popu- similar amounts of chest tube drainage, and

lation and is routinely given as an analgesic the patients in the ketorolac group had no

agent for postoperative patients, although wound bleeding compared with 1 patient in

some controversy persists about using it after the nonketorolac group who had wound bleed-

cardiopulmonary bypass surgery because of ing. One patient in the ketorolac group had GI

concern for low cardiac output syndrome and bleeding seen as small-volume coffee ground

compromised renal perfusion.11 Existing stud- nasogastric drainage with no change in hemo-

ies in children are sparse and have small sam- globin or hematocrit. These authors concluded

ple sizes. A prospective randomized study that short-term use of ketorolac after cardiac

examined bleeding risk associated with surgery did not increase the risk of postopera-

ketorolac after cardiac surgery as measured by tive bleeding in their study.

26

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 26 06/01/14 4:40 PM

VOL UME 2 5 • N U MBER 1 • JANUARY–M ARCH 2014 KE TOROLAC IN P OSTOP E RAT IVE CA RD IAC P E D IAT RICS

Several retrospective studies have evaluated bleeding requiring surgical exploration. They

the risk of bleeding in children receiving found no association between clinically signifi-

ketorolac after cardiac surgery. Another study cant postoperative bleeding and exposure to

compared postoperative bleeding as measured ketorolac (0.5 mg/kg IV every 6 hours follow-

by hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelets, and ing 1 mg/kg loading dose) for an average of 44

frank bleeding. Chest tube output was not hours. The limitations of this study include

included as a measure of bleeding in this study.6 small sample size, retrospective design, and an

A total of 4 of 53 patients had episodes of absence of measurement of chest tube output,

bleeding; none of the episodes were at the sur- blood counts, or any bleeding that did not

gical wound site, and none of the patients require surgical exploration.

experienced a decrease in hemoglobin, hema- The current literature suggests a low risk of

tocrit, or hemodynamic stability. The authors bleeding with the use of ketorolac for children

of this study concluded that, in their patients, following cardiac surgery. Various studies used

ketorolac therapy for less than 48 hours in different measures of bleeding, making it diffi-

neonates and infants does not increase the risk cult to evaluate what level of bleeding is clini-

of bleeding compared with the patients who cally significant. For example, bleeding requiring

did not receive ketorolac. blood transfusion should be categorized as clini-

Another retrospective study by Gupta et al16 cally significant because blood transfusions

evaluated the risk of bleeding for patients carry risk.17 In addition, these studies do not

receiving this drug after cardiac surgery by per- describe concurrent medications such as other

forming a chart review and controlling for anticoagulation medications, NSAIDs, or H2-

diagnosis and degree of illness severity in the blockers for GI prophylaxis. Risk of bleeding

nondrug group. The patients in this study were with the use of ketorolac based on current litera-

infants to older teenagers with a mean age of 8 ture is summarized in Table 2. Although the lit-

years. The authors do not comment on the erature supports minimal increased risk of

inclusion or exclusion of neonates or those postoperative bleeding with the use of ketorolac,

with cyanotic heart disease. The authors this conclusion is limited to short-term dosage.

defined clinically significant bleeding as The manufacturer recommends that the drug be

Table 2: Summary of Literature Review of Bleeding Risk With Use of Ketorolac

Reference Patient Population Outcomes Measured Results Ketorolac Dosing

Dawkins et al12 Infants younger Hemoglobin, No significant dif- 0.5 mg/kg IV every

than 6 mo, status hematocrit, platelet ference in hemo- 6 h for average of

postcardiac surgery, count, the number globin, hematocrit, 3.1 d

biventricular of blood transfu- platelet count,

physiology sions or the number of

blood transfusions

compared with

nonketorolac group

Gupta et al14 Neonates, infants, and Chest tube drainage, No significant 0.5 mg/kg IV every

children postcardiac wound bleeding, GI increased risk of 6 h for < 48 h

surgery/prospective bleeding bleeding compared

randomized control with control group

study

Gupta et al16 Infants and children Postoperative bleed- No significant 0.5 mg/kg IV every

postcardiac surgery/ ing requiring surgi- increased risk of 6 h for < 48 h

retrospective chart cal reoperation bleeding compared

review with nonketorolac

group

Moffett et al6 Infants younger than Signs and symptoms No significant Mean 0.44 mg/kg IV

6 mo postcardiac of bleeding, hemo- increased risk of every 6 h

surgery/retrospec- globin, hematocrit, bleeding compared

tive chart review platelets with nonketorolac

control group

Abbreviation: GI, gastrointestinal.

27

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 27 06/01/14 4:40 PM

JA LK UT W W W.A ACNA DVA NCE D CRIT ICA LCA RE .COM

discontinued after 5 days as a result of Finally, patients who undergo orthotopic

significantly increased risk of GI bleeding and heart transplants are excluded from ketorolac

renal dysfunction with dosing more than 5 days. studies because of the renal toxicity associated

with immunosuppressive medications. This

Special Populations patient group should not receive ketorolac at

Many of the studies previously discussed are any time.9 Patients who take tacrolimus have a

retrospective in design and rely on chart review risk of acute nephrotoxicity with concurrent

for patient cohorts. These studies reviewed use of NSAID medication.20 Pediatric cardiac

patient data for those who had received patients in the intensive care unit who are tak-

ketorolac postoperatively and then created a ing tacrolimus or other similar immunosup-

comparison group matched for criteria such as pressive medications are not candidates to

diagnosis, age, surgical intervention, and sever- receive ketorolac and should avoid all NSAIDs.

ity of illness, which created a selection bias for

each study and excludes many groups of Opioid-Sparing Effect

patients who were not given the drug. In addi- As previously mentioned, the most common

tion, the prospective, randomized control medications for pain control for children who

study excluded patients who were at high risk have undergone cardiac surgery are opioids

for renal dysfunction or bleeding.14 Conse- and acetaminophen.3 Opioids have well-

quently, little information or research is avail- known dose-dependent adverse effects such as

able about the safety profile of this drug in respiratory depression, hypotension, nausea/

special populations such as neonates, children vomiting, GI hypomotility, and pruritis.21

with single-ventricle physiology, and those These adverse effects can be significant for

receiving concurrent medications that could infants and children who have undergone car-

increase the risk of bleeding or renal dysfunc- diac surgery, given their potentially tenuous

tion with ketorolac. hemodynamics. Often patients are receiving

Neonatal cardiac surgery accounts for a these medications in the periextubation time

large portion of pediatric cardiac surgery.18 period when respiratory sufficiency is of vital

These patients are a high-risk group for several importance to avoid reintubation.22

reasons, including the complexity of their heart Patients who remain intubated following

disease, length of cardiopulmonary bypass surgery commonly receive continuous adminis-

time, increased amount of time spent with tration of fentanyl with as-needed dosing for

invasive support and monitoring, and altered breakthrough pain. Extubated patients often

volume of distribution and pharmacokinetics.1 receive intermittent morphine or fentanyl for

The reviewed literature does not clearly indi- breakthrough pain.3 Researchers hypothesize

cate that it is safe to give these patients that the concurrent use of ketorolac will reduce

ketorolac following cardiac surgery. the need for opioids and therefore reduce nega-

According to some reports, patients with tive adverse effects of opioids while still pro-

single-ventricle physiology receive ketorolac viding adequate analgesia.23 In one study, adult

after undergoing the Blalock-Taussig shunt, the patients after surgery received either ketorolac

Glenn surgery, or the Fontan surgery, but the and morphine or morphine only for break-

sample sizes are quite small.16 In addition, these through pain.24 Patients who received dual

patients are commonly taking low-dose aspirin therapy had a decreased need for morphine,

at baseline prior to surgery and are restarted but no significant difference in adverse effects

on this medication shortly after surgery.19 Little from opioids was reported. Another study of

discussion is found in the literature about the adults had similar findings. Patients who

use of ketorolac in patients who are taking received ketorolac in addition to morphine for

another NSAID. Further studies need to be postoperative pain had a 48% reduced need

done to evaluate the safety of this medication for morphine. No evidence of reduction of opi-

in these patients. Many postoperative cardiac oid-associated adverse effects is reported in

patients are often started on a form of antico- this study.25 The authors from both of these

agulation (eg, heparin, enoxaparin, warfarin) studies concluded that the duration of time for

for their anatomy or implanted foreign devices. which the patients were evaluated for opioid-

None of the literature reviewed here addressed associated adverse effects was inadequate.

patients receiving ketorolac who are also A small prospective trial evaluated the

receiving anticoagulation therapy. opioid-sparing effect of ketorolac on children

28

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 28 06/01/14 4:40 PM

VOL UME 2 5 • N U MBER 1 • JANUARY–M ARCH 2014 KE TOROLAC IN P OSTOP E RAT IVE CA RD IAC P E D IAT RICS

following general surgery.23 The authors found literature on a particular pain medication and

a significant opioid-sparing effect for children how it applies to a specific patient or patient

receiving concurrent ketorolac and morphine population is imperative. Knowledge of the

particularly on postoperative day 1 along with safety profile of ketorolac based on pediatric

a reduction in adverse effects from morphine, specific evidence allows advanced practice

including nausea and vomiting and respiratory nurses to appropriately and safely select

depression. Few studies to date describe the ketorolac for certain patients and educate oth-

opioid-sparing effect of ketorolac for children, ers in regard to its use in this population.

and no studies were able to describe the opioid- Table 3 highlights some considerations for pro-

sparing effect for patients who had undergone viders who are prescribing ketorolac and gives

cardiac surgery. dosing recommendations.26

Implications for Advanced Conclusion

Practice Nurses The use of ketorolac as an adjunct for the

Pain management for children undergoing treatment of pain in pediatric patients follow-

cardiac surgery is a critical element of the ing cardiac surgery is currently a controversial

postoperative period. Adequate analgesia topic. Institutional standards vary considerably

reduces physiological and psychological stress in regard to pain management strategies and

of infants and children. Use of ketorolac protocols for this patient population. Current

for 24 to 72 hours postoperatively can reduce literature supports the safe use of this medica-

breakthrough pain and the number of neces- tion at 0.5 mg/kg per dose IV every 6 hours for

sary rescue medications.23 Reduction in 48 hours following cardiac surgery. Little evi-

adverse effects of opioid medications dence is available about the efficacy or safety

could also reduce the necessity of additional of a loading dose or dosing for longer than 48

medications such as stool softeners, laxatives, hours in pediatrics. Ketorolac is contraindi-

antiemetics, and antihistamines. Finally, cated in those with a history of renal failure;

decreased use in opioid medications may pre- taking concurrent nephrotoxic, NSAID, or

vent the need for opioid taper and adverse anticoagulation medications; with clinically

effects of withdrawal. significant bleeding during or immediately fol-

For advanced practice nurses in the pediat- lowing the surgery; or with a history of GI

ric cardiac intensive care unit, pain manage- bleeding. Not enough literature is available to

ment for patients following cardiac surgery support safe use in patients younger than

should be diligent and analgesic agents should 28 days or with single-ventricle physiology.

be selected thoughtfully. Although institutions Further studies need to be completed to assess

may have protocol-driven pain management the risk factors associated with ketorolac in

pathways, being familiar with the current these special populations.

Table 3: Considerations in Dosing Ketorolac in Infants and Children

Dosing and Duration of

Therapy Monitoring Parameters Patient Selection Special Considerations

0.5 mg/kg IV every 6 h Hemoglobin, hematocrit, Infants older than 28 d Avoid in patients with

24-48 h of therapy platelet count and children intracardiac catheters or

Signs and symptoms of Biventricular physiology pacing wires with high

Initiate therapy 6-24 h

surgical site bleeding, risk of bleeding in situ

postoperatively Patients without immedi-

chest tube output, ate postoperative Initiation of H2-blocker

gastric bleeding bleeding requiring Avoid in patients receiving

Serum creatinine, blood blood transfusion or other NSAIDs or forms

urea nitrogen reoperation of anticoagulation

Urine output Patients without history

of renal failure or

receiving nephrotoxic

medications

Abbreviations: IV, intravenous; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

29

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 29 06/01/14 4:40 PM

JA LK UT W W W.A ACNA DVA NCE D CRIT ICA LCA RE .COM

14. Gupta A, Daggett C, Drant S, Rivero N, Lewis A. Pro-

REFERENCES spective randomized trial of ketorolac after congenital

1. Nichols DG, ed. Critical Heart Disease in Infants and Chil- heart surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18(4):

dren. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2006. 454–457.

2. Suominen P, Caffin C, Linton S, et al. The Cardiac Anal- 15. Dordonia PL, Della Ventura M, Stefanelli A, et al. Effect

gesic Assessment Scale (CAAS): a pain assessment of ketorolac, ketoprofen and nefopam on platelet func-

tool for intubated and ventilated children after cardiac tion. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:1046–1049.

surgery. Pediatr Anesth. 2004;14(4):336–343. 16. Gupta A, Daggett C, Ludwick J, Wells W, Lewis A.

3. Diaz LK. Anesthesia and postoperative analgesia in Ketorolac after congenital heart surgery: does it

pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Pediatr increase the risk of significant bleeding complications?

Drugs. 2006;8(4):223–233. Pediatr Anesth. 2005;15:139–142.

4. Potts A, Anderson BJ, Holford NH, Vu TC, Warman GR. 17. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Blood trans-

Dexmedetomidine hemodynamics in children after car- fusions. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/top-

diac surgery. Pediatr Anesth. 2010;20:425–433. ics/bt/risks.html. Published 2011. Accessed March 17, 2013.

5. Horn PL, Wrona S, Beebe AC, Klamar JE. A retrospec- 18. Marino BS, Wernovsky G, Greeley WJ. Single-ventricle

tive quality improvement study of ketorolac use follow- lesions. In: Nichols DG, ed. Critical Heart Disease in

ing spinal fusion in pediatric patients. Orthop Nurs. Infants and Children. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby

2010;28(5):342–343. Elsevier; 2006:789-799.

6. Moffett BS, Wann TI, Carberry KE, Mott A. Safety of 19. Canter CE. Preventing thrombosis after the Fontan

ketorolac in neonates and infants after cardiac surgery. procedure: not there yet. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(6):

Pediatr Anesth. 2006;16:424–428. 652–653.

7. Cohen MN, Christians U, HenthornT, et al. Pharmacokinet- 20. Soubhia R, Mendes GE, Mendonca F, Baptista MA, Cip-

ics of single-dose intravenous ketorolac in infants aged ullo JP, Burdmann EA. Tacrolimus and non-steroidal

2-11 months. Soc Pediatr Anesth. 2011;112(3):655–660. anti-inflammatory drugs: an association to be avoided.

8. Zuppa AF, Mondick JT, Davis L, Cohen D. Population Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:327–334.

pharmacokinetics of ketorolac in neonates and young 21. Yaster M. Multimodal analgesia in children. Eur J

infants. Am J Ther. 2009;16:143–146. Anesthesiol. 2010;27(10):851–857.

9. Reinhart DJ. Minimising the adverse effects of 22. Kloth RL, Baum VC. Very early extubation in children

ketorolac. Drug Safety. 2000;22(6):487–497. after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(4):787–791.

10. Jaggers J, Ungerleider RM. Cardiopulmonary bypass 23. Carney DE, Nicolette LA, Ratner MH, Minerd A, Baesl TJ.

in infants and children. In: Nichols DG, ed. Critical Heart Ketorolac reduces postoperative narcotic require-

Disease in Infants and Children. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, ments. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(1):76–79.

PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2006:507-529. 24. Grimsby GM, Conley SP, Trentman T, et al. A double-

11. Acharya M, Dunning J. Does the use of non-steroidal blind randomized controlled trial of continuous intra-

anti-inflammatory drugs after cardiac surgery increase venous ketorolac vs placebo for adjuvant pain

the risk of renal failure? Interactive Cardiovasc Thorac control after renal surgery. Mayo Clin. 2012;87(11):

Surg. 2010;11:461–467. 1089–1097.

12. Dawkins TN, Barclay CA, Gardiner RL, Krawczeski CD. 25. Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Miranda N, Diaz A. Comparison

Safety of intravenous use of ketorolac in infants of morphine, ketorolac and their combination for post-

following cardiothoracic surgery. Cardiol Young. operative pain. Am Soc Anesthesiol. 2005;103:

2009;19:105–108. 1225–1232.

13. Inoue M, Caldarone C, Cox PN, et al. Safety and efficacy 26. LexiComp. Indianapolis, IN: Wolters Kluwer Health;

of ketorolac in children after cardiac surgery. Intensive 2013. http://webstore.lexi.com/ONLINE-Software-for-

Care Med. 2009;35:1584–1592. Advanced-Practice-Nurses/. Accessed August 27, 2013.

30

Copyright © 2014 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

NCI-D-13-00024R1.indd 30 06/01/14 4:40 PM

You might also like

- Nuclear Medicine Therapy: Principles and Clinical ApplicationsFrom EverandNuclear Medicine Therapy: Principles and Clinical ApplicationsNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Consideration For Neonatal Surgical Emergencies: Review ArticleDocument7 pagesAnaesthetic Consideration For Neonatal Surgical Emergencies: Review ArticleArun JoseNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Consideration For Neonatal Surgical emDocument7 pagesAnaesthetic Consideration For Neonatal Surgical emLong LongNo ratings yet

- AAP Emergencies Ped Drug Doses PDFDocument20 pagesAAP Emergencies Ped Drug Doses PDFUlvionaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pearls in NephrologyDocument5 pagesClinical Pearls in NephrologyEdmilson R. LimaNo ratings yet

- BjorlDocument6 pagesBjorlaaNo ratings yet

- PCCM Suppl Mar 2016Document13 pagesPCCM Suppl Mar 2016Xavier AbrilNo ratings yet

- Kidney News Article p20 7Document2 pagesKidney News Article p20 7ilgarciaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of IM Ketorolac Tromethamine On Bleeding Time: A Prospective, Interventional, Controlled StudyDocument3 pagesThe Effect of IM Ketorolac Tromethamine On Bleeding Time: A Prospective, Interventional, Controlled StudyDaniel TelloNo ratings yet

- E46 FullDocument9 pagesE46 Fulljames.armstrong35No ratings yet

- Benefits and Risks of Dexamethasone in Noncardiac SurgeryDocument9 pagesBenefits and Risks of Dexamethasone in Noncardiac SurgeryHenry Gabriel HarderNo ratings yet

- Management of Anesthesia in A Pregnant Patient With An Unmodified Congenital Heart DiseaseDocument5 pagesManagement of Anesthesia in A Pregnant Patient With An Unmodified Congenital Heart DiseaseZakia DrajatNo ratings yet

- ACEP Ketamine Guideline 2011Document13 pagesACEP Ketamine Guideline 2011Daniel Crook100% (1)

- Effect of Ketofol On Pain and Complication After Caesarean Delivery Under Spinal Anaesthesia: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical TrialDocument4 pagesEffect of Ketofol On Pain and Complication After Caesarean Delivery Under Spinal Anaesthesia: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical TrialHaryoko AnandaputraNo ratings yet

- ACE Inhibitor in Pediatric (Jurnal Asli)Document11 pagesACE Inhibitor in Pediatric (Jurnal Asli)imil irsalNo ratings yet

- ChayapathiDocument8 pagesChayapathiVINICIUS CAMARGO KISSNo ratings yet

- RSI Post IntubationDocument8 pagesRSI Post IntubationshinjiNo ratings yet

- Diuretico en DBPDocument10 pagesDiuretico en DBPUriel MartzNo ratings yet

- Addition of Low-Dose Ketamine To Midazolam-fentanyl-propofol-Based Sedation For Colonoscopy A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled TrialDocument6 pagesAddition of Low-Dose Ketamine To Midazolam-fentanyl-propofol-Based Sedation For Colonoscopy A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled TrialRoderick Samuel PrenticeNo ratings yet

- Impact of Intra-Operative Dexamethasone After Scheduled Cesarean Delivery: A Retrospective StudyDocument8 pagesImpact of Intra-Operative Dexamethasone After Scheduled Cesarean Delivery: A Retrospective StudyMiftah Furqon AuliaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Intraoperative Epidural Anesthesia During Hepatectomy On Intraoperative and Post-Operative Patient OutcomesDocument8 pagesEffects of Intraoperative Epidural Anesthesia During Hepatectomy On Intraoperative and Post-Operative Patient OutcomesAfniNo ratings yet

- Entezami-Int. Neuroradiology 2020Document11 pagesEntezami-Int. Neuroradiology 2020Pedro VillamorNo ratings yet

- Thoracic Epidural For Modified Radical Mastectomy in A High-Risk PatientDocument2 pagesThoracic Epidural For Modified Radical Mastectomy in A High-Risk PatientBianca CaterinalisendraNo ratings yet

- Scarpelli EM, Regional Anesthesia and Anticoagulation, Narrative Review Current Considerations, IAC 2024Document9 pagesScarpelli EM, Regional Anesthesia and Anticoagulation, Narrative Review Current Considerations, IAC 2024jorge fabregatNo ratings yet

- Oschman 2011Document6 pagesOschman 2011Cee AsmatNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Oximetry Monitoring To Maintain Normal Cerebral ExplainDocument11 pagesCerebral Oximetry Monitoring To Maintain Normal Cerebral ExplainDaniel EllerNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AnestesiDocument8 pagesJurnal AnestesiapriiiiiiilllNo ratings yet

- Timing of Initiation of Renal-ReplacementDocument12 pagesTiming of Initiation of Renal-Replacementchamwick4567No ratings yet

- PharmaDocument4 pagesPharmaDave UyNo ratings yet

- Procedural Sedation - A Review Sedative Agent, Monitoring and Management of ComplicationsDocument16 pagesProcedural Sedation - A Review Sedative Agent, Monitoring and Management of Complicationsfuka priesleyNo ratings yet

- Letter: When Less Is More: Dexamethasone Dosing For Brain TumorsDocument2 pagesLetter: When Less Is More: Dexamethasone Dosing For Brain TumorsCheflak KitchenNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Sodium Nitroprusside For Controlled Hypotension in Children During SurgeryDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Sodium Nitroprusside For Controlled Hypotension in Children During SurgeryAudra Firthi Dea NoorafiattyNo ratings yet

- Consenso IccDocument15 pagesConsenso IccMaida Martinez AngelesNo ratings yet

- 0 Aet484Document7 pages0 Aet484UsbahNo ratings yet

- ASCO Antiemetic Guidelines Update Aug 2020Document18 pagesASCO Antiemetic Guidelines Update Aug 2020catalina roa zagalNo ratings yet

- Tham 2010Document13 pagesTham 2010Santosa TandiNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Major Surgery in NeonatesDocument18 pagesAnesthesia For Major Surgery in NeonatesfulkifadhilaNo ratings yet

- Tetracycline-Induced Renal Failure After Dental Treatment: Clinical PracticeDocument5 pagesTetracycline-Induced Renal Failure After Dental Treatment: Clinical Practicealyssa azzahraNo ratings yet

- Neostigmine Administration After Spontaneous Recovery To A Train-of-Four Ratio of 0.9 To 1.0Document11 pagesNeostigmine Administration After Spontaneous Recovery To A Train-of-Four Ratio of 0.9 To 1.0Juan Jose Velasquez GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Document Journal Review 4.09Document11 pagesDocument Journal Review 4.09Anonymous diwFs3MsWRNo ratings yet

- Kor 2008 Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular AnesthesiaDocument7 pagesKor 2008 Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular AnesthesiaReham Abdel HaleemNo ratings yet

- 677 FullDocument5 pages677 FullNoniqTobingNo ratings yet

- Sedacion EcmoDocument10 pagesSedacion EcmodavidmontoyaNo ratings yet

- heart failure articleDocument7 pagesheart failure articlefaraz.mirza1No ratings yet

- cancers-11-00936-v4Document27 pagescancers-11-00936-v4Hussein El-SanabaryNo ratings yet

- You Exec - KPIs - 169 - BlueDocument14 pagesYou Exec - KPIs - 169 - BlueEssa SmjNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1053077024000934 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S1053077024000934 MainalfintonNo ratings yet

- Ne W Engl and Journal MedicineDocument11 pagesNe W Engl and Journal Medicinea4agarwalNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Regional AnesthesiaDocument6 pagesPediatric Regional Anesthesiatq9prx5s5qNo ratings yet

- Antiemetics: ASCO Guideline Update: PurposeDocument18 pagesAntiemetics: ASCO Guideline Update: Purposeyuliana160793No ratings yet

- JCM NiDocument8 pagesJCM Nifufuka fukalifuNo ratings yet

- A Review of Anesthetic Effects On Renal Function: Potential Organ ProtectionDocument10 pagesA Review of Anesthetic Effects On Renal Function: Potential Organ ProtectionSianipar RomulussNo ratings yet

- AGA Institute Review of Endoscopic SedationDocument27 pagesAGA Institute Review of Endoscopic Sedationnohora parradoNo ratings yet

- Management Strategies For Primary Dysmenorrhea: 9.1 Topic OverviewDocument19 pagesManagement Strategies For Primary Dysmenorrhea: 9.1 Topic OverviewAgusdiwana SuarniNo ratings yet

- Practice Guidelines For Obstetric Anesthesia An Updated Report by The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force On Obstetric AnesthesiaDocument14 pagesPractice Guidelines For Obstetric Anesthesia An Updated Report by The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force On Obstetric AnesthesiaMadalina TalpauNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Management of The Patient With A Coronary Artery StentDocument6 pagesPerioperative Management of The Patient With A Coronary Artery StentSyahidatul Kautsar NajibNo ratings yet

- The Ceylon Medical Journal: Paracetamol Overdose: Relevance of Recent Evidence For Managing Patients in Sri LankaDocument5 pagesThe Ceylon Medical Journal: Paracetamol Overdose: Relevance of Recent Evidence For Managing Patients in Sri LankaARaniNo ratings yet

- Current trends in enhanced recovery after cesarean deliveryDocument9 pagesCurrent trends in enhanced recovery after cesarean deliveryFebbyNo ratings yet

- ==Document11 pages==skola onlajnNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Interventions in Neonates WiDocument11 pagesCardiac Interventions in Neonates WiimNo ratings yet

- Opioid-Sparing Effects of DiclofenacDocument6 pagesOpioid-Sparing Effects of Diclofenacdiogofc123No ratings yet

- Protocolo RVD Pós TXDocument9 pagesProtocolo RVD Pós TXdiogofc123No ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11897 019 00432 3Document7 pages10.1007@s11897 019 00432 3diogofc123No ratings yet

- UK Immigration HistoryDocument3 pagesUK Immigration Historydiogofc123No ratings yet

- How To Administer Intramuscular (IM) Vaccines: Client Age Injection Site Needle SizeDocument2 pagesHow To Administer Intramuscular (IM) Vaccines: Client Age Injection Site Needle Sizeemilia_sweetyNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan Pareto Mei 2022 ExecutiveDocument13 pagesPerhitungan Pareto Mei 2022 ExecutiveM. IrsyadNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - 3RDDocument8 pagesDrug Study - 3RDGreen MindedNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KetorolacDocument5 pagesJurnal KetorolacHerdinadNo ratings yet

- Study: Observational Travelers' DiarrheaDocument5 pagesStudy: Observational Travelers' DiarrheaFathah MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Module 3 NSTP1 FinalDocument7 pagesModule 3 NSTP1 FinalFrank PintoNo ratings yet

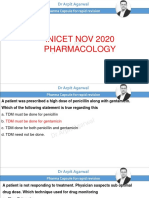

- Inicet Nov 2020 PharmacologyDocument20 pagesInicet Nov 2020 PharmacologyVISHWAKARMA RAJATNo ratings yet

- Maklumat Vaksinasi: Vaccination DetailsDocument2 pagesMaklumat Vaksinasi: Vaccination DetailsHariz ZahinNo ratings yet

- Nephrotoxic Drugs - Ready ReckonersDocument14 pagesNephrotoxic Drugs - Ready ReckonerskrgduraiNo ratings yet

- Baker Drugs DentistryDocument39 pagesBaker Drugs DentistryDentalBoardNo ratings yet

- Antihistamine Drugs Guide for Allergy ReliefDocument3 pagesAntihistamine Drugs Guide for Allergy ReliefFaten SarhanNo ratings yet

- Anticancer ChemotherapyDocument40 pagesAnticancer Chemotherapyanon_3901479100% (1)

- Dextroamphetamine: Brand Name: DexedrineDocument23 pagesDextroamphetamine: Brand Name: DexedrineSharry Fe OasayNo ratings yet

- January 2021Document36 pagesJanuary 2021rammvr05No ratings yet

- Phenytoin and Protamine SulfateDocument2 pagesPhenytoin and Protamine SulfateTintin Ponciano100% (1)

- Goat Medications 2015Document3 pagesGoat Medications 2015commanderkeenNo ratings yet

- Nexpro Uae FinalDocument13 pagesNexpro Uae Finalamr ahmedNo ratings yet

- Web Non Subsidized Imported and Locally Manufactured Under LicenseDocument80 pagesWeb Non Subsidized Imported and Locally Manufactured Under LicenseA GhNo ratings yet

- Anti FUNGAL Drugs PDFDocument70 pagesAnti FUNGAL Drugs PDFHester Marie SimpiaNo ratings yet

- Minutes Prac Meeting 26 29 October 2020 - enDocument80 pagesMinutes Prac Meeting 26 29 October 2020 - enAmany HagageNo ratings yet

- Intro To TDM and ToxicologyDocument46 pagesIntro To TDM and ToxicologyAl-hadad AndromacheNo ratings yet

- Medicine List by AmirDocument39 pagesMedicine List by AmirNomAn JuTtNo ratings yet

- Serotonin (5-HT3) Antagonist: Ondansetron SucralfateDocument6 pagesSerotonin (5-HT3) Antagonist: Ondansetron SucralfateLola LeNo ratings yet

- Diretriz SBA 2020 Anestesia Regional e AnticoagulantesDocument24 pagesDiretriz SBA 2020 Anestesia Regional e AnticoagulantesArmando MendesNo ratings yet

- Morepen Labs - Transforming To A Healthcare CompanyDocument19 pagesMorepen Labs - Transforming To A Healthcare Companyekta agarwalNo ratings yet

- 2nd Year Pharmacology PapersDocument23 pages2nd Year Pharmacology PapersMelissa PillaiNo ratings yet

- 4 Drugs Used in GastrointestinalDocument13 pages4 Drugs Used in Gastrointestinalrajkumar871992No ratings yet

- PHM - Endocrine DrugsDocument3 pagesPHM - Endocrine DrugsJeanne RodiñoNo ratings yet

- List Harga ObatDocument11 pagesList Harga Obatklinik girimukti medical centerNo ratings yet

- Daftar Nama Dan Harga Obat: Berlaku Per Maret 2020Document1 pageDaftar Nama Dan Harga Obat: Berlaku Per Maret 2020AnjelinNo ratings yet