0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7K views18 pagesEffect of Temperature on Magnetism

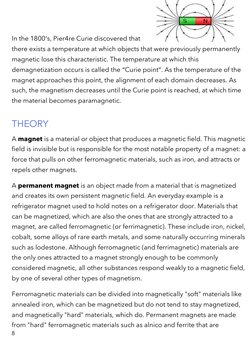

This document is a physics investigatory project report by Mukul Chowdhary on determining the effect of temperature on magnet strength. The objective was to see if colder temperatures result in stronger magnetism. Paperclips were used to measure the magnetic force of bars placed in freezing and heating conditions. Observation tables show that colder temperatures (-21 to 0 degrees Celsius) attracted more paperclips (225-275 grams), indicating stronger magnetism. In contrast, heating the magnets (0 to 50 minutes removed from heat) steadily decreased their ability to attract paperclips, showing weakening magnetism as temperature increased. The conclusion is that extreme cold strengthens magnets by slowing atoms and aligning magnetic domains, while

Uploaded by

Mukul ChowdharyCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7K views18 pagesEffect of Temperature on Magnetism

This document is a physics investigatory project report by Mukul Chowdhary on determining the effect of temperature on magnet strength. The objective was to see if colder temperatures result in stronger magnetism. Paperclips were used to measure the magnetic force of bars placed in freezing and heating conditions. Observation tables show that colder temperatures (-21 to 0 degrees Celsius) attracted more paperclips (225-275 grams), indicating stronger magnetism. In contrast, heating the magnets (0 to 50 minutes removed from heat) steadily decreased their ability to attract paperclips, showing weakening magnetism as temperature increased. The conclusion is that extreme cold strengthens magnets by slowing atoms and aligning magnetic domains, while

Uploaded by

Mukul ChowdharyCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd