Professional Documents

Culture Documents

McRae ContrastingStylesDemocratic 1997

Uploaded by

Oluwasola OlaleyeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

McRae ContrastingStylesDemocratic 1997

Uploaded by

Oluwasola OlaleyeCopyright:

Available Formats

Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-Making: Adversarial versus Consensual

Politics

Author(s): Kenneth D. McRae

Source: International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique

, Jul., 1997, Vol. 18, No. 3, Contrasting Political Institutions. Institutions politiques

contrastées (Jul., 1997), pp. 279-295

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1601344

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1601344?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

International Political Science Review (1997), Vol. 18, No. 3, 279-295

Contrasting Styles of Democratic

Decision-making: Adversarial versus

Consensual Politics

KENNETH D. MCRAE

ABSTRACT. The notion of "consociational democracy" originated from

prolonged debates in the 1950s over prerequisites for democratic stability.

The concept then spread rapidly in both Western and Third World

comparative analysis. From this base Arend Lijphart went on to develop

contrasting majoritarian and consensual models more widely applicable to

all established democratic countries. This article examines the general

conditions favorable to consensual rather than adversarial politics, and

then briefly surveys six selected countries that exemplify consensual

elements in greater or lesser degree. Its conclusion poses the question

whether consensual politics is better visualized as a coherent model or as

a series of devices and practices that can be employed piecemeal in many

situations.

Introduction

Some of the topics covered in this issue offer rather clearcut choices. In spite

few deviant cases, it is usually not difficult to decide whether a political syste

parliamentary or presidential, unitary or federal, and uses-or does not use-s

form of proportional representation at elections. Analysis can then proceed fr

there. Other topics may seem more nebulous, requiring the construction of sca

rankings, and estimates depending on how one elects to approach the problem

comparison. The present article focuses on different styles and procedures f

democratic decision-making, and it offers us a choice of approaches, dependin

how narrowly or broadly we wish to view the decision-making process.

At a first and most specific level, one can analyze the formal requirements

decision-making in key political and legal institutions. Typical examples wou

include various procedures: for reaching executive decisions; for passing a law;

0192-5121 (1997/03) 18:3, 279-17 ? 1997 International Political Science Association

SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi)

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

280 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

protecting geographical regions, or religious or ethnolinguistic minorities; for

challenging a law in the courts; and so on. At this same level, one can observe differ-

ences between legal norms and daily practice, since practice can diverge from

formal norms either by under-enforcement of formal requirements (e.g., of

language laws) or by additional requirements based on custom (e.g., conventions

concerning representativeness of cabinets). By focusing mainly on comparisons of

formal requirements, Arend Lijphart (1984) has produced an elegant contrastive

model of majoritarian and consensual systems for 21 democratic systems that will

be examined more fully below.

At a second level, one can look in each country at the decision-making process

and its norms in a much wider sense, taking the entire organization of society and

its patterns of social action as the object for study. This wider canvas includes not

only the central political arena but also local politics, citizen assemblies, decision-

making patterns in industrial relations, in religious and cultural organizations, and

so on. In this wider spectrum of decision-making, one may look for evidence of

congruence or noncongruence among different sectors, and also compare degrees

of congruence from one country to another. This second approach entails both risks

and benefits. The risks include a loss of clarity, and the possibility of greater subjec-

tivity in selecting from a wider range of evidence. The benefits include the proba-

bility of a deeper understanding of the broader political culture, and of knowing

whether it exhibits evidence of system-wide patterns. This approach also permits

us to assess for each case just how much decision-making is managed through

channels outside the formal public sector.

The terminology for this topic has varied from one author to another, and

beneath the differences in words are differences in the way that the issue has been

conceptualized and democratic regimes classified. It is obvious that all systems of

representative democracy are adversarial to some degree at certain points, for

example at elections. Similarly, all are consensus-seeking at some level, because all

democratic systems require a threshold of legitimacy in order to survive. For greater

precision, some authors have preferred to label adversarial regimes as "majoritar-

ian," while others have found this too restrictive and have preferred the term

"competitive." On the other side, authors have differed considerably in defining and

delimiting which regimes are consensual. Some democratic regimes are more

obviously and thoroughly consensual than others, and the causes and consequences

of consensual practices differ strikingly in different cases.

My intent at this stage is to leave questions of definition and terminology open,

on the simple calculation that to follow a single path at this point is to close off

other avenues of inquiry. As a consequence of this choice we may lose some preci-

sion of analysis-particularly concerning marginal or intermediate cases-but we

profit from a broader understanding that different approaches are plausible and

may yield different (and possibly incompatible) results. As the next section will

suggest, the terminology has evolved as the debate unfolds, and as emphasis has

shifted among the countries under study.

History of the Question: Evolution of an Idea

To study this topic more fully, we may follow a research strategy proposed by

Aristotle: to begin by considering something in its first origins, and then follow its

growth and development. For this purpose it is unnecessary to begin from Aristotle.

This topic has specific origins, effectively in the 1950s and 1960s, when comparative

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 281

politics was beginning to categorize systematically the different types of democratic

regime. For a generation that still recalled grave challenges to parliamentary

regimes in the 1930s, a central concern was how to maintain democratic stability.

This was often interpreted as, and measured by, the stability of ministries or

cabinets, a factor which later research has shown to be rather imperfectly correlated

with the stability of regimes or even with continuities of public policy.

One of the influential figures in this debate over stability was Gabriel Almond,

who contended in one key article of 1956 that stability is linked with political culture

and social structure. In support of this linkage, he developed a tripartite typology

of democratic regimes that contrasted a stable, culturally homogeneous group,

exemplified by the Anglo-American democracies, with a less stable, culturally

fragmented group, exemplified by the main continental European systems, plus a

third group of smaller European systems that "combine some of the features" and

"stand somewhere in between" the two other democratic categories (Almond, 1956:

392-393, 405). In subsequent writings, Almond worked towards a basically dichoto-

mous model and sought ways in which to fit cases from the rather awkward

unexplained third group into one or other of his two main original categories

(Lijphart, 1968b: 10-18; 1969: 208-212). These smaller European democracies, it

may be noted, were at this point a rarely visited, sketchily documented terra incog-

nita for most students of comparative politics.

In the 1960s the influence of the Almond model was pervasive, to the point of

ignoring or bending empirical evidence to the contrary. "Your country," declared

one comparativist to the Dutch political scientist Hans Daalder, "theoretically

cannot exist" (Daalder, 1974: 607). The Netherlands, however, not only existed but

stood out as a clear example of a system that combined political stability with an

undisputedly fragmented social structure, a persistent exception to any simple

dichotomous typology. This paradox of the mid-1960s became the starting point for

Arend Lijphart to examine more closely the working of democracy in The

Netherlands and to lay f6undations for a new category that would better explain

the presence of political stability in at least some of the cases comprising Almond's

original, loosely defined third category. Lijphart's study of accommodation among

top-level elites in Dutch politics, published in 1968, quickly became a classic and

led almost simultaneously to similar studies of several other countries.

At the World Congress of the International Political Science Association held at

Brussels in 1967, two papers heralded the arrival of the new way of thinking.

Working independently of each other and drawing on previous work targeted at

different countries, two authors challenged the prevailing orthodoxy of a direct

linkage between democratic stability and current social structure. Gerhard

Lehmbruch, who had just completed a monograph on decision-making in Switzerland

and Austria (1967), presented a paper discussing "systems in which political groups

like to settle their conflicts by negotiated agreements among all the relevant actors,

the majority principle being applicable in fairly limited domains only" (1974: 91).

Arend Lijphart, whose book on The Netherlands had not yet been published, deliv-

ered a long paper that reviewed existing literature on classification of political

systems and proposed a new category for the few apparently deviant cases that exhib-

ited both high social fragmentation and governmental stability (1968a, 1968b).

Lehmbruch referred to the practices he describes as "concordant democracy"

(Konkordanzdemokratie), and also as "proportional democracy" (Proporzdemokratie), while

Lijphart proposed the term "consociational democracy." This terminology marked a

starting point for serious comparative study of consensual democratic systems. While

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

282 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

consensus as such is by no means a new idea in Western political thought, its earlier

manifestations usually occurred in settings that preceded political democracy or

mass politics.

There was a more fundamental difference than terminology between the

approaches of Lijphart and Lehmbruch. The latter found the roots of accommoda-

tive politics in the historical political culture of the societies that he investigated,

a product of long developmental processes of the countries concerned. This view

was also shared by Hans Daalder, who saw both Switzerland and The Netherlands

as historically predisposed towards consociational politics as a result of "older tradi-

tions of elite accommodation" (Daalder, 1971). Lijphart, on the other hand, found

the sources of accommodative behavior primarily in the ability and willingness of

political elites to formulate compromises acceptable to the adherents of their

respective subcultures (McRae, 1990: 94-95). The difference was important. It

meant that consociational politics could be flexible, transferable, and potentially

exportable to newly independent countries that faced dangerously high levels of

tribal, religious, or other forms of subcultural conflict.

A third scholar whose work contributed to the early development of the new

concept was the American historian Val Lorwin, who analyzed in some depth the

phenomenon of religious and ideological segmentation in Belgium, The

Netherlands, Austria, and Switzerland. Drawing on a widespread knowledge of

European socialist and Catholic labor movements, Lorwin examined the social

forces and organizational patterns that had led to the development, preservation,

and eventually the decline of distinct Catholic or Protestant, secular liberal, or

socialist subcultures in these countries (Lorwin, 1971). The key articles of these

three progenitors of the new way of thinking, Lehmbruch, Lijphart, and Lorwin,

together with other articles on the politics and social structures of these countries,

were assembled in Consociational Democracy, a collection of readings that illustrates

the components of this formative phase of the "consociational school" (McRae,

1974).

Once enunciated, the concept of consociational or "proportional" democracy

spread rapidly. Because of its promise for many newly independent countries,

Lijphart's advocacy of building deliberate, purposive cooperation among the subcul-

tural elites of these countries, as an alternative to more forceful strategies of

integration, attracted much attention, though not without debate and skepticism

on the part of critics. Against these critics, Lijphart argued unflinchingly for

attempting consociational solutions even in the most unfavorable circumstances, on

the main ground that where consociationalism is unlikely to succeed, majoritarian

solutions stand even less chance of success.

The high point of this phase of consociationalism is represented by Lijphart's

Democracy in Plural Societies, published in 1977, a work that reviews the features and

devices of established consociational systems, the social and political conditions that

favor such systems, and the mixed pattern of success and failure in various attempts

to develop consociational systems, or specific consociational devices, in the Third

World. This book gives special attention to the post-colonial experience of former

dependencies of two leading consociational countries, Belgium and The

Netherlands, to see whether the colonial legacy from these countries has been

different. Another chapter deals with consociational elements in nonconsociational

democracies, including overviews of two countries (Canada and Israel) that the

author cautiously classified as "semiconsociational." This chapter marks a first step

towards examining consensual regimes more generally.

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 283

After the appearance of Politics in Plural Societies, Lijphart turned more system

atically to the comparative analysis of democracy in general. The result was a stud

published in 1984 under the title Democracies, which analyzed selected variables i

21 countries that had had continuously stable democratic regimes from 1945 to 1980

and were also large enough for statistical analysis. The central aim of this book wa

to investigate contrasting patterns of democratic government and to relate these t

social systems. The result was an elaboration of two distinct models of democracy

a majoritarian or "Westminster" model, best exemplified by the United Kingdom

or New Zealand, and a consensus model, best exemplified by Switzerland or

Belgium. The contrasting characteristics of these two models will be listed in the

next section as a starting point for further analysis.

Lehmbruch also built upon his earlier work on "concordant" or "proportional"

democracy, though his later writings in English adopted the increasingly popular

term "consociational democracy." His later work moved in two directions: (1) the

conditions faced by consociational democracies in international relations; and (2

the relationships between consociational political systems and systems of economi

representation and decision-making known as liberal corporatism or neocorporatism

(Lehmbruch, 1975; Schmitter and Lehmbruch, 1979). The spreading concept of

liberal corporatism opened up an entire new range of consensual practices in th

world of work, industrial relations, and incomes policy, a development that woul

have implications for important areas of public policy and political decision-making,

but for considerations of space these developments will not be separately followe

up here.

Lijphart's TWo Models

In two introductory chapters of Democracies (1984: chaps. 1, 2), Lijphart identifies

nine and eight main characteristics respectively of his majoritarian and consensual

models. These may be concisely listed and compared as follows:

1. The majoritarian model posits one-party executive power in cabinets

which command a majority of parliamentary seats; the consensual model

shares executive power among all important parties in parliament, prefer-

ably in a broad coalition government.

2. The majoritarian model supposes cabinet control of parliament and a

fusion of executive-legislative authority; the consensual model is marked

by separation of executive and legislative authority or by coalition cabinets

whose fate is often in the hands of the parliamentary parties.

3. The majoritarian model leans to asymmetrical bicameralism and legisla-

tive dominance by the lower house; the consensual model gives more

powers to the second chamber or upper house, and typically uses it to

protect minority interests of one kind or another.

4. The majoritarian model prefers and works towards a two-party system;

the consensual model is open to multiparty politics (though some

countries establish a threshold for parliamentary representation of small

parties).

5. The majoritarian model presupposes a one-dimensional party system

along a left-right axis; the consensual model accepts the possibility of

multiple cleavages in society and a multidimensional party system to

reflect them.

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

6. The majoritarian model prefers elections in single-member constituencies

by the plurality method; the consensual model uses some form of propor-

tional representation to achieve more faithful representation of voter

preferences.

7. The majoritarian model assumes a unitary, uniform, centralized system

of government; the consensual model often provides autonomous areas for

minority interests through federalism or decentralization of authority.

8. The majoritarian model is built on comprehensive parliamentary

sovereignty, and hence does not require a written constitution; the consen-

sual model requires a written constitution, amendable only by some form

of special procedure, as a means of minority protection against undiluted

majority rule.

9. Lijphart's ninth characteristic of the majoritarian or "Westminster"

model is that purely representative systems are not favorable to direct

democracy, and hence resort to referenda sparingly. As his later analysis

shows, however, this is not really a distinguishing feature from consensual

systems as a group, because these also are based on representative

systems. The major deviant example here is Switzerland, which in the

period examined held more than twice as many federal referenda as the

other 20 countries combined (1984: 30-32, 201-204).

The two models developed in this fashion are of course ideal types. There are no

pure cases of the models in the real world, nor is there any reason-other than the

convenience of academics and their students-why there should be. Lijphart himself

lists several discrepancies between the majoritarian model and its nearest examples

in the world of existing democracies, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. For

the United Kingdom, he notes minority Labour cabinets and periods of fragile

majorities in the House of Commons; small third parties (Liberals, Social

Democrats); ethnic nationalism in Scotland and Wales and discussion of devolution

of power to those countries; and the Northern Ireland question, with its regional

parliament for Ulster and experiments with proportional representation. Deviations

of a different sort surfaced after Britain's entry into the European Community in

1973, because the Community thereby acquired the power to legislate directly in

certain policy areas and to challenge British laws in the European Court (1984:

9-16).

For New Zealand, a small, socially homogeneous society, the deviations from the

pure model were even smaller. This country has had a unicameral parliament since

1950, and it made greater-than-average use of referenda between 1945 and 1980.

Neither of these characteristics could be seen as a major departure from the model.

More significantly, New Zealand provided separate parliamentary representation

for its Maori minority in four (later five) larger territorial districts, with a separate

voting register for Maori electors in these constituencies (Lijphart, 1984: 16-20;

McLeay, 1980). For both Britain and New Zealand, most of these deviations from

the formal model could be seen as marginal rather than central elements of the

political system, although some would contend that Britain's accession to the

European Community (later the European Union) represented a surrender of the

sovereignty of Parliament in areas covered by the treaties of accession.'

Lijphart illustrates the eight features of the consensual model with examples

from Switzerland and Belgium. Yet it is clear even at a superficial level that these

two countries approach questions of minority protection in different ways and in

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 285

different contexts. Lijphart's examples may thus imply that there is no single,

coherent model of consensual democracy. As he himself notes in the preface to

Democracies, "I start out with an analysis of the majoritarian model, from which I

derive the consensus model as its logical opposite" (1984: xiv). This procedure does

not guarantee a coherent countermodel. In this sense his consensual "model" differs

significantly from the more tightly knit model of consociational democracy in his

earlier writings.

Consensual devices, practices, and customs can therefore be found in a wide

variety of situations. They depend upon the nature of the protection sought and the

most promising strategies for achieving it. In my analysis that follows, therefore, I

shall retain Lijphart's two pairs of cases that he selects to typify his two models,

but I shall also draw illustrations from countries such as Canada and Finland that

can be ranked somewhere between majoritarian and consensual systems. While

Lijphart sometimes refers to a "majoritarian-consensual continuum," he also note

in his concluding chapter: "The majoritarian model approximates a constitutional

blueprint, whereas the consensus model merely supplies the general principles on

which constitutional provisions can be based but which entail a number of furthe

choices that have to be made" (1984: 32-33, 210). In my own analysis I shall

examine later whether or not the two models should be visualized along a single

linear dimension or continuum.

Sources of Consensual Politics

The limitation of Arend Lijphart's two models, as he develops them in De

is that they are in large part descriptive and static. With minor except

analysis refers mainly to the period from 1945 to 1980, and his primary

with how these democracies function-in law and in practice-rather than

have developed. From these cases and their patterns of societal pluralism

ops both rational and empirical indicators for deciding when consensual d

to be recommended. This is of course consistent with Lijphart's long-held

in plural societies the most significant variable is the capacity and willin

the various segmental elites to act rationally and produce compromise

acceptable to their communities. In his view, such behavior is not confined by

or place, or environmental circumstances.

However, other authors who have analyzed consociational or consensual

including Lehmbruch, Daalder, Lorwin, and many authors of single-country s

have paid closer attention to developmental factors. Practically all of the

racies analyzed by Lijphart, with the possible exception of Israel and Japa

long developmental history of representative and democratic governmen

from about 100 years to several centuries. These developmental patterns

opportunity to take a longer view, and to add some sort of dynamic dim

the analysis.

My own working hypothesis is that consensual systems or devices develop primar-

ily from three types of situation: (1) a long-term growth of consensual practices and

attitudes that become embedded in the political culture, often prior to the arrival

of mass politics, and incorporated gradually in formal institutions; (2) an institu-

tional, legal, or constitutional compromise or package arrived at through inter-elite

negotiation and bargaining, to establish a workable regime or to resolve a specific

problem or deadlock; (3) an external environment, whether of short or long

duration, that is sufficiently threatening to require domestic political groups to

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

286 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

compromise or set aside internal divisions in order to assure the independence or

survival of the system itself.

These are not, of course, watertight compartments. We can expect to find

overlapping combinations of these three categories and cumulative reinforcement

of the consensual characteristics of the regime. But consensual practices and behav-

ior undoubtedly can develop, as Lijphart has frequently pointed out, without a prior

consensus-oriented political culture if other conditions are sufficiently favorable.

Further, consensual devices or practices may occur in otherwise majoritarian

regimes when circumstances require it. One of the clearest examples is territorial

federalism in systems that are adversarial in other respects. Similarly, consensual

systems can develop weaknesses that require repair through more adversarial

means. Such devices may lack congruency with other parts of a political system, but

they may be functional for that system if they help to resolve a specific problem.

Of the 21 democracies considered by Lijphart, Switzerland and The Netherlands

are probably the best examples of long-term, slowly evolving political cultures toler-

ant of societal differences. Daalder (1971) gives a perceptive summary of the

relevant long-range factors: their common geopolitical position on the fringes of the

Holy Roman (i.e., German) Empire; the historical absence of any strong centraliz-

ing tradition; their economic focus on mercantile cities and trade routes; the persis-

tence of "ancient pluralism" in new forms in modernized pluralist societies; and

successful accommodation of religious diversity. The Netherlands shares some

aspects of the heritage of the Low Countries with Belgium, but Belgian experience

has also been shaped by periods of Spanish and Austrian dynastic power, Jacobin

democracy, and strong anti-Orangist traditions after separation from the United

Netherlands in 1830. As a result, the sources of Belgian political culture are more

varied.

In a broader European context, the former Imperial lands seem more receptive

to a continuing pluralist political culture than the countries that experienced

centralizing national monarchies (England, Scotland, France, Spain), and especially

those areas of the Empire that escaped later monarchical centralization under

Austria or Prussia. For the Imperial lands in central Europe there was an institu-

tional base for this in the religious Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which established

the geographic separation of Roman Catholics and Lutherans (cujus regio, ejus religio)

in a pattern that still marked Germany until well into the twentieth century. A

second pattern of long-term religious segmentation-this one nonterritorial-can

be seen in some successor states to the Ottoman Empire, where it appears, among

other examples, in the social and legal organization of Israeli democracy.

Regarding the second category, the idea of a package or agreement as a founda-

tion for a society or regime has a long and honorable history in pre-democratic

liberal thought, under the generic label of social contract theory. While classical

liberal theory envisions a hypothetical original compact to establish a society or set

up a form of government or both (in double-contract theorists), most modern,

historically documented cases of pacts or agreements have been negotiated among

elites of rival factions, parties, social classes, or religious or ethnolinguistic groups.

A far-reaching example is the previously mentioned Peace of Augsburg, which was

confirmed and expanded at the end of the Thirty Years War in the Treaty of

Westphalia of 1648.

In more recent times there are many examples of pacts or agreements to estab-

lish a regime or to resolve a crisis by negotiated agreements among the contend-

ing parties. Lijphart's original study of political accommodation in The Netherlands

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 287

focused on the Pacificatie of 1917, accomplished by a small neutral power at the

height of World War I. The Swiss federal constitution-makers of 1848 successfully

reconciled Protestant and Catholic cantons in the wake of a brief civil war over the

Catholic Sonderbund in 1847. In the 1840s Canadian leaders from Upper and Lower

Canada cooperated to make workable the British-imposed Act of Union of 1840,

and when this regime broke down in deadlock in the 1860s a wider grouping of

party leaders combined to devise the federation of 1867.

American history has further examples. A key compromise at the Federal

Convention of 1787, allowing southern states to count their slave populations at 60

percent of actual numbers for purposes of representation and direct taxation,

overcame a critical division between northern and southern delegates and made a

federal union possible. The Missouri Compromise of 1821, admitting Missouri as a

slave state but barring slavery from all the remaining territory of the Louisiana

Purchase, allowed four further decades of North-South cultural coexistence until

the system collapsed under increasing strains in the late 1850s, resulting in a costly

war. The Civil War effectively put an end to various states' rights theories, reduced

the power of state governments, and left the United States a more majoritarian

society.

The third source of consensual practices is a threatening external environment.

The threat may be of either short or long duration. Among the short-term sources

are coalition governments in wartime or in other crises. A well-known example is

the Conservative-Labour coalition led by Winston Churchill from 1940 to 1945 in

the United Kingdom, the very archetype of the majoritarian model. In Finland,

where coalition government was already the norm, the war years from 1941 to 1943

saw an all-party coalition that included even Finland's fascist party (IKL). Austria

resorted to broad Catholic-Socialist coalitions after 1945 in order to surmount the

difficulties of the Allied four-power military occupation and establish legitimacy for

the Second Republic. This practice continued for 21 years, to be succeeded after

1966 by alternating majority governments at federal level that nevertheless largely

adhered to earlier practices of proportionality and consociational politics as

accepted rules of the game (Pulzer, 1969).

Some countries have faced hostile external environments on a longer-term basis.

Finland has experienced such a situation intermittently ever since its separation

from Sweden in 1809, both as a Grand Duchy under the Russian tsars and after

independence in 1917 as a neighbor of the Soviet Union. The proximity of a large

and powerful neighbor has left a persistent and complex imprint on Finland's polit-

ical institutions, political behavior, and collective mentality. Israeli democracy,

surrounded from its foundation by hostile neighboring states, has also been largely

shaped in response to external forces.

Four Systems Considered

I have noted above that when Lijphart developed his majoritarian model of democ-

racy, he also mentioned specific deviations from it in the two countries closest to

the model, the United Kingdom and New Zealand. What remains to be explored is

whether we can treat the alternative consensual model in the same way, an exercise

that Lijphart did not pursue. This section will therefore examine Lijphart's two

major consensual examples, Switzerland and Belgium, for both consensual and

nonconsensual elements. To these will be added two further examples in which

neither adversarial nor consensual features are so clearly predominant, Finland and

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

Canada. These four additional cases should be visualized not as abstract models but

as integrated, working political systems that reflect the complexities of the real

world. Because of space limits, however, these profiles must be brief. I am looking

for the operational mainsprings of each system. For more rounded, comprehensive

portraits, one may consult full-length country studies of Switzerland, Belgium, and

Finland (McRae, 1983, 1986, and forthcoming 1997).

In Switzerland, a central feature of the system is proporz, or proportional fairness,

as Lehmbruch has emphasized. It applies in a double sense, at the levels both of

distributional fairness and of political, administrative, or judicial representation.

The "magic-formula," four-party federal executive, with proportions unchanged

since 1959, is perhaps the best-known feature of this form of power-sharing.2 Even

more widely known is Switzerland's decentralized federalism, which allows many

federal laws to be administered by the cantons according to their priorities and also

leaves residual legislative power to the cantons.

The cantons show similar patterns of proporz and multiparty executives, even in

those where a single party may control a majority of seats in the cantonal legisla-

ture, though a few small cantons still practice direct democracy through annual

citizen assemblies or Landsgemeinden. Swiss federalism is also close-knit between

levels of government. The cumul des mandats allows cantonal and communal politi-

cians to sit concurrently in the federal parliament, a practice that on balance

promotes intergovernmental cooperation rather than confrontation.

The origins of consensual attitudes in long-term political culture have produced

Swiss leaders with finely honed skills in the early detection and mediation of subcul-

tural conflicts. Though not universal, these skills can be documented at many points

since the Treaty of Stans in 1481. Five centuries of accommodative leadership have

given Swiss pluralist values the status of a treasured national asset, and while one

might doubt the depth of this sentiment in popular culture, there are few Swiss

who would openly attack it.

The chief "nonconsensual" device that many scholars have seen in Swiss politics

is the referendum and its forms of direct democracy. However, Swiss referenda are

of different kinds. Those for constitutional amendments, including those resulting

from citizen initiatives, require a double majority of total voters and voters in a

majority of cantons, thus affording a degree of minority protection. Referenda

resulting from challenges to parliamentary legislation, as well as citizen-inspired

constitutional initiatives, represent a safety valve, a remedy for too much inter-elite

consensus in a system that lacks a viable alternative government. As such, they can

offset legislative mistakes or omissions, and can thus be beneficial for the function-

ing of the system.

In Belgium, periods of Liberal and Catholic one-party hegemony in the

nineteenth century ended with the rise of a third Socialist pillar after franchise

reform in 1893. Belgian social structure then became highly segmented into three

distinct pillars orfamilies spirituelles, making coalition government the usual form.

Flemish language aspirations, beginning as a quest for individual language rights

in the 1850s, went on to become a drive for regional priority and even territorial

exclusivity for Dutch in Flanders in the 1920s and 1930s. In the process, the strongly

unitary Belgian state of the nineteenth century was reoriented gradually towards

federalism after 1965. In the 1990s this federalization is not quite complete, but

the quest for language accommodation has been under way for more than a century.

Its achievement, through long and often bitter debate and negotiation, represents

a considerable triumph for consensual-and consociational-politics.

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 289

The new-model federalism of Belgium defies simple description. Essentially, it is

an asymmetrical double federalism of Byzantine complexity, which devolves listed

powers in two layers from the central government to three cultural communities

(Dutch-speaking, French-speaking, and German-speaking) and three nonmatching

economic regions (Flanders, Wallonie, and Brussels-Capital). The two layers also

function asymmetrically. There are counterbalanced minorities of Flemish Socialists

and Walloon Catholics, of Flemings in Brussels and Francophones in Belgium as a

whole, and a central aim of the system is to protect these minorities through the

negotiating strength of the corresponding majority groups elsewhere in the system.

Under the tensions accompanying constitutional reform in the 1970s, each of the

three traditional parties was split into separate language-based parties, and these

functioned alongside three regional parties whose drive for regionalization had

helped to force linguistic splits in the traditional parties.

The means for assuring the various forms of minority protection under the new

institutions are numerous: devices for guaranteed linguistic parity in the cabinet,

in the top-level public service, in parliamentary committees, and in broadcasting;

proportionality in funding and fair representation in the public service and public

corporations, the diplomatic corps, higher education and scientific research; "alarm-

bell" procedures to protect linguistic minorities in parliament or in Brussels-

Capital, and ideological minorities in the new community councils; measures to

assure cultural autonomy in broadcasting and education, including the splitting of

bilingual universities into separate, officially unilingual institutions. This list could

be lengthened, but the key principles remain parity at the top, fair representation

at lower levels, and community autonomy wherever feasible.

Because the language laws and constitutional reform have met prolonged and

stiff resistance from supporters of the former unitary system, Belgium has invested

heavily in control agencies and enforcement mechanisms to assure compliance with

policies that ultimately derive their strongest support from the Flemish majority.

The paradox is that policies of power-sharing and cultural autonomy, worked out

by arduous negotiation in the central parliament, seem to require the continuing

authority of that parliament to give legitimacy to enforcement agencies. Belgian

political culture, like the Swiss, recognizes the need for patient negotiation and

finding a mean (middelmatisme), but unlike the Swiss version it tends to view the

resulting consensus less positively, not as a civic virtue but as a necessary evil.

In Finland, the political system was strongly influenced by external forces both

before and after 1917, but for half a century after independence domestic politics

was acutely adversarial. These years brought three disastrous wars, a renewed

second wave of language conflict, and continuous bitter ideological divisions

stemming from the Red-White civil war of 1918 that accompanied the struggle for

independence. This period saw the outright banning of communism from 1930 to

1944, the outlawing of fascist parties and rightist organizations at Soviet insistence

after 1944, and the exclusion of communists from cabinet posts for 18 years from

1948 to 1966 as a precaution against an apprehended coup d'etat. To the extent

that the constitution permitted, majoritarian politics predominated.

The later 1960s brought a more consensual climate and a trend to broader coali-

tions. The communists were readmitted to government in 1966, the conservatives-

after four decades of almost total exclusion-in 1987. Cabinets became more durable.

In 66 years from 1917 to 1983 Finland had 62 governments, but the next 12 years

saw only three, each of which lasted a full four-year parliamentary term. The most

recent coalitions have also spanned a wider ideological range: the five-party "rainbow"

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

coalition formed in 1995 grouped conservatives, communists, and one Green Party

minister in the same cabinet. In industrial relations and incomes policy, there has

been a parallel evolution from hard-line militancy to highly institutionalized negoti-

ation involving all major economic interest groups, with the result that Finland since

the 1960s has moved visibly closer to a Scandinavian model of government through

widespread consultation and consensus (Helander and Anckar, 1983; Elder, Thomas,

and Arter, 1988).

The institutional framework for parliamentary democracy under the 1919

Constitution is interesting for two special features. First, Finland has fluctuated

between presidential government and a more parliamentary system, depending on

the salience of foreign policy issues-where the president carries special powers and

responsibilities-and the temperament of presidential incumbents. Presidential

power was carried to great heights during Urho Kekkonen's 25 years in office, but

since 1981 it has receded under his two lower-key successors. Second, special-major-

ity procedures in parliament were specified not only for constitutional amendments

but for some categories of taxation and economic measures that are considered to

infringe constitutionally protected property rights of citizens. These required either

a two-thirds or a five-sixths majority of votes cast, depending on the procedure used.

Further, even ordinary laws passed by simple majority could be deferred until after

the next election by a vote of one-third of the members, a striking provision for a

temporary minority veto. These procedures rewarded consensual behavior and made

a minimum-majority coalition less valuable than a broader one (Arter, 1984:

262-280; Anckar, 1988). Somewhat ironically, they are being phased out in the

1990s as Finland adjusts to its new membership in the European Union.

In Canada, the federal parliament at first sight looks quite similar to the

Westminster model of the United Kingdom or New Zealand. The electoral system

is based on single-member constituencies, and hence gives bonuses-sometimes

enormous ones-to parties that have a plurality either nationally or in a specific

region. There is an expectation of one-party cabinets that control a majority in the

House of Commons, and an aversion to formal coalitions when no party wins a

majority. The second chamber is weak, resting on appointment rather than election,

and it originally represented not the provinces of the federation but the three (later

four) geographical regions of the country. Much the same Westminster model

appears in the 10 provincial governments. While the two-party system remains the

normative model at both federal and provincial levels, the caprices of the electoral

system have produced either one-party landslides or three-party (or even four-party)

situations on many occasions. Some smaller provinces have seen an occasional sweep

of all seats by a single party.

Canada, however, is a federation, and federations require a division of powers, a

written constitution, and in most cases judicial review, all considered to be consen-

sual devices to protect minority interests of one kind or another. This being said,

one may argue that Canadian federalism operates in a more adversarial fashion

than Swiss federalism. In Canada there are separate sets of legislators at federal

and provincial levels, and some provinces have separate federal and provincial party

organizations. There are separate federal and provincial bureaucracies, with areas

of overlap and rivalry. During chronic constitutional impasse and conflict since the

late 1960s, there has been an increased resort to federal-provincial "executive

federalism" through regular meetings of first ministers to resolve intergovernmen-

tal differences. Increasing public reaction against this practice led some provinces

to require a provincial referendum on any projected constitutional amendment, but

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 291

this has made significant constitutional amendment all but unattainable. While

federalism is normally a consensual device, some federal systems clearly operate in

more consensual fashion than others.

The constitutional changes of 1982 included a comprehensive Charter of Rights,

containing important human rights guarantees that restricted the powers of all

levels of government in Canada. This had the effect of removing a wide range of

issues from the political arena of negotiation and compromise to one of authorita-

tive determination by the judiciary. Since the best-known and most widely cited

external model for Canada is the United States, the Charter has clearly increased

the propensity of Canadians to contest human rights issues through American-style

litigation.

On closer examination, the Canadian federal system illustrates the working of

what Lijphart has termed incongruent federalism, that is, a federation in which the

component units differ from one another and from the federation as a whole in

their social and cultural characteristics (1984: 179-180). These differences have led

different provinces to develop differing forms of accommodation for religious and

linguistic minorities. Concerning religion, most provinces provide separate public

education systems for Catholics and non-Catholics, through parallel, separately run

school systems at the local level. Concerning language, Quebec was created in 1867

with guarantees and expectations of ethnocultural dualism, but since the 1960s it

has increasingly moved towards official unilingualism. Manitoba entered the

Confederation in 1871 with institutions to accommodate religious and linguistic

dualism on the model of Quebec, but all this was swept away by the 1890s owing

to the pressure of advancing English-speaking settlement. New Brunswick has

moved in the opposite direction, from English unilingualism before the 1960s to

official bilingualism and formal recognition of cultural duality in the 1980s. These

examples are a reminder that consensual behavior may vary from one time period

to another and from one region to another, even within a single political regime.

These sketches of Switzerland, Belgium, Finland, and Canada touch only the

highlights of these four political systems. They are not systematic, and cannot be

made so in such a limited space. They can, however, be improved and regularized

somewhat if we place them in a framework of the eight elements of Lijphart's

consensus model. This is done in Table 1, which for contrast also includes Lijphart's

two preferred examples of majoritarian democracy, New Zealand and the United

Kingdom. In this table Lijphart's list of elements is represented by the first nine

points, which include separate listings for territorial and nonterritorial federalism

(7 and 8). To these I have added the idea of limited government backed by a charter

of rights (10), because these generally aim to protect all citizens including minor-

ity groups, whether as individuals or in collectivities. The remaining four categories

(11-14) list a few specialized or unusual arrangements that emerge from a closer

look at the six countries in the table.

The classifications in Table 1 are rather crude and also tentative. Some require

qualification, and some would be better represented as scales than as simple "yes"

or "no" alternatives. Nevertheless, the main aim is to illustrate the method and

assess the broad incidence of consensual devices and practices. What the table

perhaps fails to represent fully is the pattern of the underlying political cultures,

which could be measured more directly by appropriate survey research. Among the

added dimensions that Lijphart does not include, the notion of territorial special

status occurs in only one of these six cases, but other examples occur elsewhere,

including Greenland and the Faroe Islands (Denmark), Catalonia (Spain), or the

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

TABLE 1. Consensual Elements in Six Selected Democracies.

Feature Switzerland Belgium Finland Canada NZ UK

1. Executive-level Yes Yes Yes No No No

powersharing

2. Separation of powersa Yes No Yes No No No

3 Balanced bicameralismb Yes Yes N/A No N/A No

4. Multiparty systemc Yes Yes Yes No No No

5. Multidimensional Yes Yes Yes Yes No No

party systemd

6. Proportional Yes Yes Yes No No No

representation

in elections

7. Territorial federalism Yes Yes No Yes No No

8. Nonterritorial No Yes No Yes No No

federalisme

9. Written constitution Yes Yes Yes Yes No No

with possible minority

veto

10. Limited government, No No Yes Yes No No

charter of rights

11. Special procedures Yes Yes Yes Yes No No

available in legislative

processf

12. Separate minority No No Yes No Yes No

electoral registersg

13. Non-official No No Yes Yes No No

representative bodiesh

14. Territorial special No No Yes No No No

statusi

aPartial separation in Finland.

b Unicameral parliaments in Finland and

c Excludes minor or regional parties in C

d Excludes small nationalist parties in Un

e Includes community councils (Belgium)

f Includes: referendum challenge to law

deferment motions in Finland; notwiths

g Includes Sami register (Finland) and M

h Includes Svenska Finlands Folkting (F

i Includes Aland islands (Finland).

South Tyrol (Italy). It seems li

racies would add still more dimensions to Table 1 than have been indicated here.

Conclusion: Is There a Consensus Model?

This article has been more exploratory than definitive. Its conclusions will

priately brief. The findings from the selected examples and some further

cast doubt upon the notion of a coherent or integrated consensus mod

stage a better frame for analysis might be represented as a wheel or c

with spokes radiating outwards from a centre, as in Figure 1. These spo

sent various consensual devices, practices, and strategies that offer alternat

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. MCRAE 293

FIGURE 1. Consensual Devices and Strategies as Variationsfirom the Majoritarian Model.

improvements to a centralized, majority-oriented, integrated model. This is not to

suggest, however, that a centralized model must precede consensual practices

historically. Previous studies show strong evidence to the contrary.

Figure 1 represents mainly a listing of the elements in Table 1, slightly

rearranged to facilitate analysis. If we compare this figure to a clock-face, the upper

right quadrant concerns devices for fair representation and power-sharing in a

central parliament (12 to 3), while the next four categories (4 to 7) concern diffu-

sion of power in the system and possibilities of citizen or group protection against

government. The next two (8 and 9, building on 5 and 7) refer to territorial diffu-

sion, while 10 represents forms of nonterritorial self-government. The figure leaves

one more position (11) for miscellaneous special devices such as those listed above

in Table 1, and this list would undoubtedly grow longer if the study were extended

to the rest of the 21 democracies.

Analytically speaking, one may arrange these elements into groupings and

clusters in a variety of ways. In spatial or geographic terms, the consensual alter-

natives to the unitary majoritarian model are (1) territorially decentralized options;

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 Contrasting Styles of Democratic Decision-making

(2) corporate federalism or cultural autonomy options; and (3) shared-power options

within the same political arena. Two further dimensions of some importance are (a)

the relative power and resources (demographic, economic, and cultural) of the

groups concerned, and (b) the range-large or small-of matters to be regulated by

consensual methods. These dimensions will not be examined further in this article,

but they constitute a starting point for a more systematic study of policy choices in

various types of plural societies. What also calls for further inquiry is which of these

elements occur normally in clusters, which ones may be normally incompatible with

others (at least with respect to a given group in a given political system), and which

ones are neutral with respect to others. When these patterns have been further

investigated both logically and empirically, we shall understand whether it is better

to view consensual democracy as a coherent integrated model or as a more diverse

collection of devices, procedures, practices, and culturally embedded states of mind.

Notes

1. However, New Zealand's position as the purest example of the Westminster model wa

cast in doubt by the general election of October 1996, held under a new law instituting

proportional representation along German lines. The outcome was a parliament with no

majority party, two months of hard negotiations to form a coalition government, and

formal interparty agreement on policy issues. The new electoral system represents

major departure from the model, but whether the deviation will prove temporary

permanent remains to be seen.

2. After 1959 Switzerland's seven-member Federal Council was chosen on a continuing basi

of two members each for the Radicals, Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, pl

one member for the Swiss People's Party (formerly the Farmers' Party). Further conven

tions assure an appropriate balance in linguistic and regional representation normall

four or five German speakers out of seven, and each of the seven representing a diffe

ent canton.

References

Almond, G.A. (1956). "Comparative Political Systems."Journal of Politics, 18: 391-409.

Anckar, D. (1988). "Evading Constitutional Inertia: Exception Laws in Finland." Scandinavi

Political Studies, 11: 195-210.

Arter, D. (1984). The Nordic Parliaments: A Comparative Analysis. London: Hurst.

Daalder, H. (1971). "On Building Consociational Nations: The Cases of The Netherlan

and Switzerland." International Social ScienceJournal, 23: 355-370. (Reprinted in McRae,

1974.)

Daalder, H. (1974). "The Consociational Democracy Theme." World Politics, 26: 604-621.

Elder, N.C.M., A.H. Thomas, and D. Arter (1988). The Consensual Democracies?: The Government

and Politics of the Scandinavian States. (Rev. ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Helander, V. and D. Anckar (1983). Consultation and Political Culture: Essays on the Case of

Finland. Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica.

Lehmbruch, G. (1967). Proporzdemokratie: Politisches System undpolitische Kultur in der Schweiz u

in Osterreich. Tiibingen: Mohr.

Lehmbruch, G. (1974). "A Non-Competitive Pattern of Conflict Management in Lib

Democracies: The Case of Switzerland, Austria and Lebanon." In Consociational Democra

(K.D. McRae, ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Lehmbruch, G. (1975). "Consociational Democracy in the International System." Euro

Journal of Political Research, 3: 377-391.

Lijphart, A. (1968a). The Politics of Accommodation: Pluralism and Democracy in the Netherla

(Rev. ed., 1975.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

KENNETH D. McRAE 295

Lijphart, A. (1968b). "Typologies of Democratic Systems." Comparative Political Studies, 1

3-44.

Lijphart, A. (1969). "Consociational Democracy." World Politics, 21: 207-225. (Reprinted in

McRae, ed., 1974.)

Lijphart, A. (1977). Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration. New Haven and

London: Yale University Press.

Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One

Countries. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Lorwin, V.R. (1971). "Segmented Pluralism: Ideological Cleavages and Political Cohesion in

the Smaller European Democracies." Comparative Politics, 3: 141-175. (Reprinted in McRae,

ed., 1974.)

McLeay, E.M. (1980). "Political Argument about Representation: The Case of the Maori

Seats." Political Studies, 28: 43-62.

McRae, K.D. (ed.) (1974). Consociational Democracy: Political Accommodation in Segmented Societies.

Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

McRae, K.D. (1983ff.). Conflict and Compromise in Multilingual Societies. Waterloo, Ontari

Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Volume 1. Switzerland (1983); Volume 2. Belgium (1986

Volume 3. Finland (forthcoming 1997).

McRae, K.D. (1990). "Theories of Power-Sharing and Conflict Management." In Conflict a

Peacemaking in Multiethnic Societies (J.V. Montville, ed.). Lexington, MA, and Toronto

Lexington Books.

Pulzer, P. (1969). "The Legitimizing Role of Political Parties: The Second Austrian Republic

Government and Opposition, 4: 324-344. (Reprinted in McRae, ed., 1974.)

Schmitter, P.C. and G. Lehmbruch (eds.) (1979). Trends toward Corporatist Intermediatio

Beverly Hills and London: Sage.

Biographical Note

KENNETH D. McRAE is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Carleton University

in Ottawa. He is a past president of the Canadian Political Science Association and

a former research supervisor for the Canadian Royal Commission on Bilingualism

and Biculturalism. His professional interests focus on comparative politics and

especially plural societies, as well as Western political thought. His most recent

books are three volumes in the five-part project Conflict and Compromise in

Multilingual Societies, dealing with Switzerland (1983), Belgium (1986), and Finlan

(1997). ADDRESS: Department of Political Science, Carleton University, 112

Colonel By Drive, Ottawa K1S 5B6, Canada.

Acknowledgements. This article is based in part on a larger investigation of plural societi

published under the title of Conflict and Compromise in Multilingual Societies (McRae, 1983ff

am grateful for research support from the Killam Programme of the Canada Council an

the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

This content downloaded from

196.27.128.77 on Fri, 23 Jun 2023 13:38:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- How Electoral Institutions and Social Cleavages Interact to Shape Party SystemsDocument27 pagesHow Electoral Institutions and Social Cleavages Interact to Shape Party SystemsDragamuNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 24 Jan 2021 23:40:29 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 24 Jan 2021 23:40:29 UTCmarting91No ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis of Major Political SystemsDocument20 pagesComparative Analysis of Major Political SystemsMir AD BalochNo ratings yet

- Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970From EverandPolitical Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970No ratings yet

- 04 Norris - Choosing Electoral Systems PDFDocument17 pages04 Norris - Choosing Electoral Systems PDFHristodorescu Ana-IlincaNo ratings yet

- STEPANSKACH - Parliamentarism Vs PresidentialismDocument23 pagesSTEPANSKACH - Parliamentarism Vs Presidentialism948vhrsvnrNo ratings yet

- Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach: Research ArticlesDocument21 pagesConceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach: Research ArticlesJoel CruzNo ratings yet

- The Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceDocument66 pagesThe Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceRó StroskoskovichNo ratings yet

- The Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceDocument18 pagesThe Nuts and Bolts of Empirical Social ScienceFermilyn AdaisNo ratings yet

- David Meyer-Conceptualizing Political OpportunityDocument37 pagesDavid Meyer-Conceptualizing Political OpportunityThays de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Wiley Center For Latin American Studies at The University of MiamiDocument6 pagesWiley Center For Latin American Studies at The University of MiamiandrelvfNo ratings yet

- Norms GameDocument18 pagesNorms GameMiguel GutierrezNo ratings yet

- (Journal of Politics Vol. 18 Iss. 3) Almond, Gabriel A. - Comparative Political Systems (1956) (10.2307 - 2127255)Document20 pages(Journal of Politics Vol. 18 Iss. 3) Almond, Gabriel A. - Comparative Political Systems (1956) (10.2307 - 2127255)Edward KarimNo ratings yet

- Framing Democracy: A Behavioral Approach to Democratic TheoryFrom EverandFraming Democracy: A Behavioral Approach to Democratic TheoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Toward A Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and PraxisDocument27 pagesToward A Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and PraxisSarah De100% (1)

- Determinants of LegitimacyDocument26 pagesDeterminants of LegitimacyMohammad Vaqas aliNo ratings yet

- American Political Science AssociationDocument19 pagesAmerican Political Science AssociationEsteban GómezNo ratings yet

- Democratization As Deliberative Capacity Building: 1 16 July 2008Document20 pagesDemocratization As Deliberative Capacity Building: 1 16 July 2008andrej08100% (1)

- Middle Class Size Impacts Democracy: Study of Structural LinkageDocument23 pagesMiddle Class Size Impacts Democracy: Study of Structural Linkagegeorgemlerner100% (1)

- Limitations of Rational-Choice Institufionalism For The Study of Latin American Politics"Document29 pagesLimitations of Rational-Choice Institufionalism For The Study of Latin American Politics"Vicente PaineNo ratings yet

- Decision-Making in Committees: Game-Theoretic AnalysisFrom EverandDecision-Making in Committees: Game-Theoretic AnalysisNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Democracy and Its DeterminantsDocument40 pagesThe Meaning of Democracy and Its DeterminantsManohar GiriNo ratings yet

- Coppedge Et. Al. - Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy. A New ApproachDocument21 pagesCoppedge Et. Al. - Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy. A New ApproachBea AguirreNo ratings yet

- The Politics, Power and Pathologies of International OrganizationsDocument110 pagesThe Politics, Power and Pathologies of International OrganizationsAbdullah Farhad0% (1)

- Democratic Peace Thesis DefinitionDocument8 pagesDemocratic Peace Thesis Definitionjessicatannershreveport100% (1)

- Formal Models of Legislatures: Abstract and KeywordsDocument28 pagesFormal Models of Legislatures: Abstract and KeywordsAlvaro VallesNo ratings yet

- Waligorski Democracy 1990Document26 pagesWaligorski Democracy 1990Oluwasola OlaleyeNo ratings yet

- SIDDHARTHABAVISKARWhat DemocracymeansDocument22 pagesSIDDHARTHABAVISKARWhat Democracymeanscharly56No ratings yet

- Why Democracies Ban Political PartiesDocument31 pagesWhy Democracies Ban Political PartiesVasile CioriciNo ratings yet

- DemocracyDocument301 pagesDemocracyTihomir RajčićNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Comparative PoliticsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics Comparative Politicsafeascdcz100% (1)

- The Priority of Democracy: Political Consequences of PragmatismFrom EverandThe Priority of Democracy: Political Consequences of PragmatismNo ratings yet

- Lehoucq & Taylor - 2019 - Conceptualizing Legal Mobilization PDFDocument28 pagesLehoucq & Taylor - 2019 - Conceptualizing Legal Mobilization PDFEscuela EsConAccionesNo ratings yet

- Party Systems and Voter AlignmentsDocument27 pagesParty Systems and Voter AlignmentsLauraPimentelNo ratings yet

- The Policy Process Rebecca SuttonDocument35 pagesThe Policy Process Rebecca SuttonHassan SajidNo ratings yet

- Why Do Democracies Break DownDocument22 pagesWhy Do Democracies Break DownwajahterakhirNo ratings yet

- Schneider Schmitter 04 Democratic TransitionDocument33 pagesSchneider Schmitter 04 Democratic TransitionburcuNo ratings yet

- Democracy Promotion DissertationDocument5 pagesDemocracy Promotion DissertationProfessionalPaperWritersHartford100% (1)

- Petracca (289-319)Document32 pagesPetracca (289-319)miggyNo ratings yet

- Political Participation and Three Theories of Democracy: A Research Inventory and AgendaDocument24 pagesPolitical Participation and Three Theories of Democracy: A Research Inventory and AgendaDiego Morante ParraNo ratings yet

- Forgerock ProjectDocument49 pagesForgerock ProjectAhmad M Mabrur UmarNo ratings yet

- Schlager and Blomquist. 1997Document24 pagesSchlager and Blomquist. 1997Mehdi FaizyNo ratings yet

- Morlino Hybrid RegimesDocument24 pagesMorlino Hybrid RegimesIoana Corobscha100% (1)

- SoutheastAsiasPolitical 1967Document48 pagesSoutheastAsiasPolitical 1967Keshor YambemNo ratings yet

- Perspectives on Future Trends in Electoral Behavior ResearchDocument11 pagesPerspectives on Future Trends in Electoral Behavior ResearchAmado Rene Tames GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Political Parties Research Paper TopicsDocument4 pagesPolitical Parties Research Paper Topicskxmwhxplg100% (1)

- Political Hegemony and Social Complexity: Mechanisms of Power After GramsciFrom EverandPolitical Hegemony and Social Complexity: Mechanisms of Power After GramsciNo ratings yet

- Variações Da Democracia AlemanhaDocument30 pagesVariações Da Democracia AlemanhaLevi OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Jurgen Habermas - Political Communication in Media Society - Does Democracy Still Enjoy An Epistemic DimensionDocument16 pagesJurgen Habermas - Political Communication in Media Society - Does Democracy Still Enjoy An Epistemic DimensionAlvaro EncinaNo ratings yet

- How Party Systems and Social Movements InteractDocument16 pagesHow Party Systems and Social Movements InteractJorge JuanNo ratings yet

- Simmons TheoriesinternationalDocument29 pagesSimmons TheoriesinternationalPaula CordobaNo ratings yet

- Herman Democratic PartisanshipDocument34 pagesHerman Democratic PartisanshipAnonymous Z8Vr8JANo ratings yet

- What Kind of Democracy Do We All SupportDocument31 pagesWhat Kind of Democracy Do We All SupportEnriqueNo ratings yet

- Nota StrategicDocument2 pagesNota StrategicFakhruddin FakarNo ratings yet

- Profile Creation CA2Document15 pagesProfile Creation CA2AarizNo ratings yet

- Shooting An ElephantDocument2 pagesShooting An ElephantShilpaDasNo ratings yet

- Kap 04 SparskruvarDocument17 pagesKap 04 SparskruvarbufabNo ratings yet

- Grammar-EXTRA NI 4 Unit 5 Third-Conditional-Wishif-Only Past-Perfect PDFDocument1 pageGrammar-EXTRA NI 4 Unit 5 Third-Conditional-Wishif-Only Past-Perfect PDFCristina LupuNo ratings yet

- Aqeelcv New For Print2Document6 pagesAqeelcv New For Print2Jawad KhawajaNo ratings yet

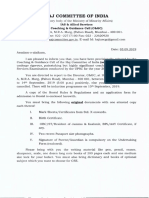

- Haj Committee of India: Tat Tory o Yoft e Ry I yDocument11 pagesHaj Committee of India: Tat Tory o Yoft e Ry I ysayyedarif51No ratings yet

- Matthew 9:18-26 Jesus Raises A Dead Girl and Heals A Sick WomanDocument1 pageMatthew 9:18-26 Jesus Raises A Dead Girl and Heals A Sick WomanCasey OwensNo ratings yet

- John D. Woodward JR., Nicholas M. Orlans, Peter T. Higgins-Biometrics-McGraw-Hill - Osborne (2003) PDFDocument463 pagesJohn D. Woodward JR., Nicholas M. Orlans, Peter T. Higgins-Biometrics-McGraw-Hill - Osborne (2003) PDFZoran Felendeš0% (1)

- IpoDocument43 pagesIpoyogeshdhuri22100% (4)

- Beasts of BurdenDocument2 pagesBeasts of BurdenGks06No ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document48 pagesChapter 11Rasel SarkerNo ratings yet

- Legal Studies Book v8 XIDocument184 pagesLegal Studies Book v8 XIMuskaan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Strategy Assignment 2 ScriptDocument5 pagesCorporate Strategy Assignment 2 ScriptDelisha MartisNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Placido T. Amo Senior High SchoolDocument12 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Placido T. Amo Senior High SchoolMary Cherill UmaliNo ratings yet

- d59687gc10 Toc GLMFDocument14 pagesd59687gc10 Toc GLMFmahmoud_elassaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Reading and Analysis of Primary Sources 2Document7 pagesChapter 7 Reading and Analysis of Primary Sources 2Ace AbiogNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument3 pagesCase StudyCrystal HolgadoNo ratings yet

- MS - International Reporting ISAE 3000Document166 pagesMS - International Reporting ISAE 3000zprincewantonxNo ratings yet

- Home Power Magazine - Issue 132 - 2009 08 09Document132 pagesHome Power Magazine - Issue 132 - 2009 08 09Adriana OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Empiricism, Sensationalism, and PositivismDocument43 pagesEmpiricism, Sensationalism, and PositivismJohn Kevin NocheNo ratings yet

- Application For Admission To Master of Computer Applications (MCA) COURSES, KERALA: 2010-2011Document5 pagesApplication For Admission To Master of Computer Applications (MCA) COURSES, KERALA: 2010-2011anishbaiNo ratings yet

- Ethical Theories and Principles in Business EthicsDocument4 pagesEthical Theories and Principles in Business EthicsMuhammad Usama WaqarNo ratings yet

- 61 Ways To Get More Exposure For Your MusicDocument17 pages61 Ways To Get More Exposure For Your MusicjanezslovenacNo ratings yet

- Leonardo MercadoDocument1 pageLeonardo Mercadoemmanuel esmillaNo ratings yet

- Octavian GogaDocument2 pagesOctavian GogaAna Maria PăcurarNo ratings yet

- Aim High 2 Unit 8 TestDocument2 pagesAim High 2 Unit 8 TestnurNo ratings yet

- 575 2 PDFDocument6 pages575 2 PDFveritas_honosNo ratings yet

- Slide Show On Kargil WarDocument35 pagesSlide Show On Kargil WarZamurrad Awan63% (8)

- The Divine ServitorDocument55 pagesThe Divine ServitorlevidinizNo ratings yet