Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brand 2

Uploaded by

brunnaheiderichOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brand 2

Uploaded by

brunnaheiderichCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620 626

Brand personality and human personality: Findings from ratings of familiar Croatian brands

Goran Milas , Boris Mlai 1

Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar, Maruliev trg 19/1, p.p. 277, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Received 1 July 2005; received in revised form 1 April 2006; accepted 1 June 2006

Abstract The present article focuses on two main problems: determining the factor structure of personality ratings of familiar Croatian brands and determining how different levels of data aggregation can affect the dimensionality and the nature of extracted factors. Following Aaker's seminal study [Aaker, J. Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research 1997; 24: 347356], which aims to identify the dimensions of brand personality, this study attempts to relate brand personality to personality dimensions derived from the natural language. In the first study, a sample of 55 students rate the familiarity of 111 brands represented in the categories of a Croatian creation and Croatian quality. Subsequently, ten brands are selected on the basis of mean familiarity and representation in various product categories (food, beverages, medicine and cleaning products). In the second study, an exhaustive Croatian taxonomy of personality descriptors [Mlai B, Ostendorf F. Taxonomy and Structure of Croatian Personality-descriptive Adjectives. European Journal of Personality 2005; 19: 117152] serves as a basis for the construction of a 90item inventory that covers the 45 facets from the AB5C model [Goldberg LR. International Personality Item Pool. A Scientific Collaboratory for the Development of Advanced Measures of Personality and Other Individual Differences. 6 June 2005. 20 April 2005. http://ipip.ori.org/ipip/]. A large sample of students (267) rate the personality of the ten selected brands using the 90-item inventory. The results of exploratory factor analyses of brand personality are discussed in respect of previous research, the lexical approach, and the possible effects of different levels of data aggregation on the dimensionality of the obtained factor structure. 2007 Published by Elsevier Inc.

Keywords: Brand personality; Personality structure; Lexical approach; Big-Five model; Data aggregation

1. Introduction In the last two decades, researchers interested in the concept of brand personality have witnessed a convergence of research that focuses on the two main constituents of this concept: brand characteristics and human personality. Acceptance of the lexical approach to human personality (De Raad, 2000) as an important branch of personality psychology has resulted in the emergence of the Big-Five model of personality description (Goldberg, 1993). Due to its comprehensiveness, the Big-Five is often conceived as an integrative framework in personality research (Goldberg and Rosolack, 1994). The emergence of a shared

Corresponding author. Tel.: +385 1 4886 803. E-mail addresses: Goran.Milas@pilar.hr (G. Milas), Boris.Mlacic@pilar.hr (B. Mlai). 1 Tel.: +385 1 4886 812. 0148-2963/$ - see front matter 2007 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.06.011

model in human personality may also serve as a guide for the creation of a common framework in the field of brand personality. After Aaker's (1997) seminal article, which identifies the brand personality dimensions of Sincerity, Excitement, Competence, Sophistication and Ruggedness, a new way of conceiving the brand personality construct, with the Big-Five human personality as a metaphor, began to emerge. The study that follows (Aaker et al., 2001) aims to replicate Aaker's (1997) American brand personality dimensions in other cultures. However, studies in Japan and Spain show varied results. Similar to research using the lexical approach to human personality (Church et al., 1998; Di Blas and Forzi, 1998), the study by Aaker et al. (2001) identifies, apart from common brand personality dimensions, additional emic (Berry, 1969) dimensions, specific to the cultures of Japan and Spain. A study by Caprara et al. (2001), which examines the brand personality of 12 mass-market brands in the Italian market and uses a

G. Milas, B. Mlai / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620626

621

measure developed from Roman Italian personality taxonomy (Caprara and Perugini, 1994), is of particular interest to the present study. Caprara et al. (2001) first use an emic lexical measure in the field of brand personality and show that a fivefactor structure is not replicated when describing brands. The results support a two-dimensional solution that resembled Digman's (1997) and personality dimensions. Although Caprara et al. (2001) are skeptical about the suitability of human personality dimensions for the descriptions of brands, one of the possible reasons for the poorer five-factor replication in their study might be in the measure used. The adjectives targeted directly at the Big-Five level of abstraction are criticized as a measure too broad for specific human behavior description (Hendriks et al., 1998). Likewise, in a brand personality context, it can be hypothesized that a somewhat lower level of abstraction, such as the AB5C model (Hofstee et al., 1992) could be useful for brand personality description. 2. Theory and problems Research on brand personality that describes either the personality of global brands or local Croatian brands does not exist in Croatia. However, because a Croatian human personality taxonomy that identifies the Croatian emic lexical factors, similar to the Big-Five factors, was developed recently (Mlai and Ostendorf, 2005), it is now possible to investigate the personality of brands in the Croatian market using an emic lexical measure. The lexical approach in personality psychology follows a simple rationale, The most important individual differences in human transactions will come to be encoded as single terms in some or all of the world's languages (Goldberg, 1993, p. 26). Since Aaker's (1997) definition of brand personality has been criticized as being too wide and loose (Azoulay and Kapferer, 2003), the researchers of this study accept the definition of brand personality as the unique set of human personality traits both applicable and relevant to brands (Azoulay and Kapferer, 2003, p.151). In view of the previous two quotations (Goldberg, 1993; Azoulay and Kapferer, 2003), the relevance of a human personality lexical measure in the study of brand personality is clearly evident. Moreover, according to the emic/etic difference in human personality studies, it would be valuable to additionally apply an indigenous measure of personality, if researchers are interested in the brand personality of local brands. Thus, rather than using an instrument from another culture, such as in the studies that developed from the work of Aaker (1997), the researchers of this article develop a brand personality measure pertinent to the culture of Croatia and the AB5C model. The present article also deals with some methodological ambiguities that could have had an obscuring effect on previous research findings. In her pioneering work on brand personality, Aaker (1997) correlates 114 personality traits across 37 brands, and the scores of each brand on each personality trait are averaged across subjects. However, this kind of analysis leads to possible interpretational problems for several reasons. As Austin et al. (2003) argues, by employing this procedure all withinbrand variance is removed and the factor analysis results are

based exclusively on between-brand variance. Although results obtained in this way may be useful in producing a framework for evaluating brands across a broad range of product categories, their use is very limited for evaluating individual brands within specific product categories. Hence, obtaining results by using Aaker's method may have inherent serious limitations regarding the generalizability of the framework (Austin et al., 2003). Neglecting within-brand variance is also inappropriate if one wants to study individual reactions to brands and resulting behavior (Bosnjak et al., 2006). The problem of data aggregation is especially evident if individual-level data are not congruent with aggregated data (Ostroff, 1993). One may reason that the individual ratings of brands are more saturated with random error, while aggregated responses for each brand are a more accurate representation of each brand's public perception. If one assumes that means (aggregated responses) reflect true scores for each brand and individual judgments only add some error variance, then using the former in factor analysis is a preferable approach. However, if the information included in individuallevel data is not essentially the same as information from the aggregated data, then the study can not recommend the factor analysis of means. For example, with regard to the case of brands, individual judgments may reflect brand personality, while aggregated results (means) may reflect the suitability of attributes for different products. Analysis of aggregated data would thus result in the absence of a personality structure found while judging a total group of brands even if it exists at the individual level. However, performing a factor analysis on correlations between ratings of a single brand could also be considered as imperfect. Ratings of a single brand produce lower variance, just as a multitude of ratings of a single person would. The consequences are lower correlations and ultimately less clear-cut factor structure. One possible solution might be to include a multitude of different brands in the same analysis, just as one does with factorizing traits across persons. To summarize, the researchers of this study are convinced that at least some differences in results regarding the dimensionality and factor structure of brand personality, specifically different levels of data aggregation, are attributable to different methodological approaches. It seems plausible to hypothesize that excluding within-brand variance, as well as concentrating only on within-brand variance can produce results of limited generalizability. Therefore, the two specific problems pursued in this study are 1) identification of the personality structure of familiar Croatian brands, using a measure from the AB5C model, and 2) determining how different levels of data aggregation affect dimensionality of the factor structure. 3. Method 3.1. Finding familiar Croatian brands Familiar global brands such as Coca-Cola soft drinks, Nike and Reebok athletic products, IBM computers, McDonald's restaurants, Lego toys, and various automobile brands are well established in the Croatian market. This has been the case since Croatia's economy became more accessible in the early nineties.

622

G. Milas, B. Mlai / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620626

However, the local Croatian brands that survived the transition from the socialist economy to the free market economy or those that have emerged in the last fifteen years are of particular interest in this article. The researchers define the top brands as the ones carrying the trademarks Croatian quality and a Croatian creation which the Croatian Chamber of Commerce awards annually. The Croatian brands in the former category stand for exceptional quality while the brands in the latter category represent not only high quality, but also a genuine Croatian product. At the beginning of this research, 75 brands hold the trademark Croatian quality and 36 brands are distinguished as a Croatian creation. Since the Croatian Chamber of Commerce continually awards new brands, the current number of brands in the categories of Croatian quality and a Croatian creation is 147 and 76, respectively. Since the study focuses on well known Croatian brands, in the first phase of this research a sample of 55 students (33 females, 22 males) rate the familiarity of 111 brands from the categories of a Croatian creation and Croatian quality. The students are enrolled in the School of Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Zagreb and their task is to rate their familiarity with a particular brand, using a five-point scale (from 1 completely unfamiliar with, to 5 completely familiar with). Following the students ratings, the researchers select 10 brands on the basis of familiarity and the brands representation in various product categories (food, beverages, medicine and cleaning products). Those brands include: Cedevita (an instant vitamin beverage), Bajadera (nougat sweets), Karlovako pivo (lager beer), Sumamed (an azithromycin medicine), ipi ips (chips), AB kultura (dairy product), Vegeta (seasoning), Gavrilovieva salama (salami), Jamnica (mineral water) and Faks helizim (detergent). All brands chosen have an average rating over 4.60. 3.2. Brand personality instrument As hypothesized above, a measure from the AB5C model (Hofstee et al., 1992) can be useful for brand personality

description as a compromise between broad dimensions such as the Big-Five and specific behavior description. The AB5C model is different to other five-factor models in the sense that the items (or adjectives) the model represents are viewed as combinations of factors rather than pure factor items, with the inclusion of primary and secondary factor loadings. The AB5C model represents each of the five Big-Five domains (Extraversion I, Agreeableness II, Conscientiousness III, Emotional Stability IV and Intellect V) with 9 bipolar facets in each domain. One of the facets is always factor pure (e.g., I+/I+ versus I/I) and the other 8 facets are combinations of a particular domain with all other domains (e.g., I+/II+ to I+/ V). Goldberg's (2005) 450 item measure covers all 45 facets from the AB5C model with 10 short statements in each facet. However, that instrument is rather extensive and some of the statements are not relevant in brand personality research such as Talk to a lot of different people at parties (I+/I+) or Would never cheat on my taxes (II+/III+). Instead, the researchers construct a 90-item inventory to cover Goldberg's (2005) 45 AB5C facets, using the results from an exhaustive Croatian taxonomy of personality descriptive-terms (Mlai and Ostendorf, 2005). Guided by two criteria, the content similarity and the empirical results of factor analyses with large samples of subjects that provided self and peer-ratings, the researchers choose two adjectives in each facet that are the best approximations of those two criteria. They assemble the 90 items in random order. 3.3. Subjects and procedures The participants in this study include 267 University of Zagreb students (65 males, 201 females, one did not report gender), ages ranging from 18 to 31 years (M = 20.4, SD = 1.7). The students are enrolled in the School of Social Sciences and Humanities in Zagreb. They rate the perceived personality of four brands using 90 items from the brand personality instrument described above. Each adjective is rated on a 5-

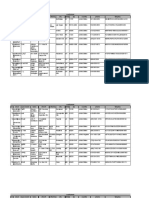

Table 1 Summary results of principal component analysis on brand personality including data from separate brands (between subject variance), brands averaged across subjects (between-brands variance) and subjects brands (combined between subject and between-brands variance) Component 1 Cedevita Bajadera Karlovako pivo Sumamed ipi-ips AB-kultura Vegeta Gavrilovi salama Jamnica Faks Brands averaged across subjects Subjects brands I/E I/C E C/I E C/I, (ES) E/I A/C, ES E/I C/E C/I/A/ES/(E) C/(ES) Component 2 C/(ES) C C/(ES, I) A/(ES) C I/E C/(ES) I/(E) A/(I) A/(ES) E/(I, A, ES) E Component 3 (E) E A/C E A A A E C/ES I/E ? A Component 4 A A (I) (I) ? ? (ES) ? ? I Component 5 (ES) (ES)

Note. The components that are not retained according to a Scree plot are marked with a dash (). The components that are retained but are not interpretable are marked with a question mark (?). E Extraversion; A Agreeableness; C Conscientiousness; ES Emotional Stability; I Intellect. Parentheses indicate weak factors with less than 10 significant projections.

G. Milas, B. Mlai / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620626

623

point Likert scale (from 1 = adjective describes this brand completely inaccurate to 5 = adjective describes this brand completely accurate). Due to the length of the rating procedure (each brand is rated with 90 adjectives), the researchers develop three sets of brand ratings. The Cedevita brand, due to its high familiarity, is included in each set, and the other three brands only appear in one particular set. The subjects also report how often they use each brand on a five-point scale (from 1 = very rarely to 5 = very often). 3.4. Data analysis To identify brand personality dimensions, the researchers apply a principal component analysis both to the individual subject and brand level (averaged across subjects), comparing them in terms of similarity with the Big-Five description framework. As a final step, they also apply a principal component analysis to the subject brand level, treating each evaluation of a brand as a separate case. Each subject is then represented with four rows; the whole matrix for analysis has 1048 rows. The three levels of aggregation correspond to factorizing different sources of variance: between subjects, between brands and combined between subjects and between brands. The study uses a Scree plot of eigenvalues (Cattell, 1966) to select the number of components to be retained. The researchers apply Varimax rotations after they determine the number of factors to be retained. After performing the analysis on subject brand level, the number of rows permits a replicability analysis using Everett's (1983) method. The principal goal of the described procedure is to improve the external validity by ascertaining that the retained components are not a product of chance but robust and stable dimensions appearing regardless of the sample. Everett's method consists of dividing the sample randomly into two subsamples and then performing a component analysis while retaining various numbers of factors on both. After Varimax rotation, factor score coefficients are computed and the matrix of standardized scores is multiplied with those scores to obtain two sets of factor scores for each number of retained factors. The correlation between these two sets reflects the congruence of components indicating the number of stable factors that need to be retained from the data. 4. Results Visual inspection of the Scree plot of eigenvalues based on brand ratings (between subject variance) indicates that in most cases three or four components should be retained. However, when the analysis is performed on the subject brands matrix (combined between subject and between-brands variance), the Scree plot indicates that five components should be retained. As a consequence of these results, the researchers retain the number of components indicated by the Scree plot, and rotate them into Varimax simple structure position. Table 1 summarizes the main findings of the analyses performed on the different levels of data aggregation with labels for each factor on the basis of the rotated factor structure matrices. Interested researchers can obtain full

factor structure tables for each analysis from the authors upon request. The rotated factor structure based on the correlations between ratings of brands averaged across subjects (betweenbrands variance) shows the least resemblance to the one expected by the Big-Five model. The two identifiable components are a blend of markers of various dimensions. Both dimensions consist of very heterogeneous items and can hardly be assigned suitable labels. However, one of them seems to group the items indicating positive attitudes towards work while the other combines items reflecting a positive affect. Extracted components do not resemble the two-factor structure reported by Caprara et al. (2001) or Digman's (1997) and personality dimensions. Factor structures obtained from the analysis of individual ratings of the separate brands (between subject variance), on average show modest resemblance to the expected Big-Five descriptive model. Some of them highly correspond to the BigFive (ipi-ips), while others show very low resemblance. However, none of the factors describing brand personality have the clarity of those usually found in self or peer description of human personality. Table 1 shows that Emotional Stability appears most infrequently as a separate dimension in descriptions of brand personality. On the other hand, Extraversion and Agreeableness appear most frequently. Conscientiousness and Intellect only rarely form separate factors, but are usually dominant in a mixture of markers indicative of several dimensions. The most frequent combinations of factors are those that combine items belonging to Intellect and Extraversion or Intellect and Conscientiousness. Although one cannot speak of a straight forward Big-Five structure while describing brands, it is obvious that it is less ambiguous than in the case of judgments averaged across subjects. This supports the assertion that using brand means in analysis obscure real brand personality structure rather than eliminate measurement error. However, factor analysis performed on correlations between ratings of a single brand also leads to serious problems that are addressed in the introduction. Ratings of a single brand produce lower variance, just as a multitude of ratings of a single person does. The consequences are lower correlations and ultimately less clear-cut factor structure. To avoid this problem, the researchers perform an analysis on all 10 brands taken together (combined between subject and between-brands variance), just as one would study human personality taking together a large number of different persons. Table 2 presents the results of the analysis at the subject brands level of aggregation. As one can conclude from Table 2, the resulting factor structure of brand personality in general resembles the Big-Five structure, although this structure has many anomalies. Emotional Stability is a weak factor and represents the greatest departure from the structure expected by the five-factor model. Moreover, none of the rotated components represents a clear-cut factor in the sense that it gathered only the expected items. A lack of simple structure particularly appears in the first rotated component, which saturates many items that intentionally belong to other dimensions. To check the robustness of the obtained five-factor structure, the researchers also perform a

624

G. Milas, B. Mlai / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620626

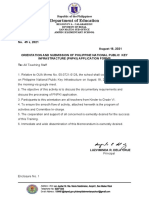

Table 2 Varimax-rotated five-factor structure of brand ratings from the inventory based on AB5C model (subject brands level of aggregation) PL C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A I I I I I I I I I I SL I I E C I A A ES E A C ES E ES ES E A A C I E C ES ES C A A A ES C I ES C I E ES C C E ES I I A ES I C E A C I ES ES E E ES A C E C ES A I I ES Croatian term Organiziran Uredan Ustrajan Vrijedan Pedantan Radian Racionalan Sistematian Ozbiljan Marljiv Savjestan Dosljedan Uporan Poman Revan tedljiv Maran Strog Pustolovan Drutven Otvoren Spontan Temperamentan Govorljiv Aktivan Prijateljski Odvaan Neukrotiv Samouvjeren Prodoran Drueljubiv Susretljiv Poduzetan Uvjerljiv Komunikativan Staloen Suutan Saalan Popustljiv Osjeajan Saaljiv Ponizan Obazriv Tolerantan Svesrdan Poten Topao Dobroduan Pravedan Uviavan Sentimentalan Dobronamjeran Srdaan Kooperativan Dubokouman Misaon Mudar Mislen Otrouman Bistrouman Analitian Bistar Pametan Pronicljiv English translation Organized Orderly Persevering Sedulous Pedantic Hard working Rational Systematic Serious Industrious Conscientious Consistent Persistent Mindful Eager Thrifty Assiduous Severe Adventurous Sociable Open Spontaneous Temperamental Talkative Active Friendly Daring Unruly Self confident Competitive Companionable Obliging Enterprising Persuasive Communicative Composed Sympathetic Pitiful Complying Compassionate Commiserative Humble Regardful Tolerant Affable Honest Warm Good hearted Just Considerate Sentimental Well intentioned Hearty Cooperative Profound Reflective Wise Contemplative Sharp witted Quick witted Analytical Bright Smart Astute C 0.72 0.71 0.67 0.66 0.65 0.65 0.64 0.64 0.63 0.59 0.56 0.55 0.55 0.45 0.45 0.41 0.38 0.35 0.06 0.04 0.12 0.07 0.02 0.03 0.19 0.13 0.29 0.06 0.42 0.24 0.01 0.15 0.43 0.53 0.06 0.64 0.17 0.05 0.05 0.15 0.11 0.22 0.37 0.29 0.25 0.36 0.12 0.27 0.44 0.41 0.10 0.34 0.12 0.37 0.31 0.23 0.43 0.45 0.47 0.38 0.34 0.49 0.52 0.39 E 0.16 0.02 0.30 0.24 0.00 0.22 0.01 0.15 0.15 0.21 0.12 0.13 0.41 0.15 0.21 0.15 0.20 0.02 0.76 0.73 0.71 0.68 0.66 0.65 0.64 0.62 0.61 0.61 0.58 0.57 0.56 0.49 0.48 0.44 0.41 0.01 0.15 0.07 0.14 0.28 0.03 0.13 0.21 0.30 0.41 0.25 0.33 0.36 0.16 0.24 0.16 0.29 0.36 0.46 0.11 0.18 0.12 0.10 0.20 0.32 0.13 0.28 0.27 0.34 A 0.00 0.14 0.04 0.14 0.20 0.09 0.13 0.12 0.13 0.19 0.40 0.08 0.04 0.40 0.36 0.25 0.20 0.05 0.03 0.18 0.12 0.23 0.07 0.17 0.05 0.26 0.04 0.04 0.09 0.08 0.22 0.24 0.08 0.04 0.09 0.21 0.70 0.69 0.67 0.63 0.60 0.58 0.54 0.54 0.48 0.47 0.46 0.46 0.45 0.42 0.38 0.29 0.28 0.24 0.27 0.23 0.20 0.21 0.14 0.17 0.13 0.14 0.15 0.20 I 0.28 0.14 0.01 0.16 0.31 0.20 0.30 0.19 0.27 0.34 0.25 0.18 0.04 0.26 0.16 0.03 0.47 0.22 0.13 0.09 0.04 0.01 0.16 0.14 0.11 0.12 0.30 0.22 0.21 0.23 0.04 0.07 0.29 0.16 0.10 0.08 0.27 0.18 0.03 0.13 0.19 0.03 0.22 0.06 0.12 0.24 0.04 0.14 0.18 0.17 0.04 0.10 0.01 0.28 0.70 0.67 0.62 0.59 0.57 0.56 0.56 0.49 0.48 0.45 ES 0.05 0.07 0.00 0.17 0.01 0.11 0.12 0.09 0.23 0.03 0.07 0.02 0.10 0.16 0.05 0.00 0.08 0.54 0.09 0.17 0.17 0.13 0.02 0.03 0.12 0.36 0.14 0.29 0.10 0.12 0.11 0.15 0.07 0.09 0.05 0.04 0.02 0.08 0.05 0.26 0.16 0.17 0.14 0.17 0.17 0.22 0.40 0.34 0.10 0.06 0.03 0.40 0.24 0.11 0.00 0.03 0.06 0.13 0.04 0.08 0.13 0.06 0.08 0.16

G. Milas, B. Mlai / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620626 Table 2 (continued) PL I I I I I I I I ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES ES SL E ES A A E C C E C A A C C A A I I E ES I ES I C E E E Croatian term Domiljat Poetian Stvaralaki Kreativan Introspektivan Imaginativan Matovit Svestran Hladnokrvan Neosjetljiv Bezosjeajan Flegmatian Odmjeren Nerazdraljiv Smiren Spokojan Pribran Sabran Stabilan Priseban Uravnoteen Oputen Umjeren Sretan Nenametljiv Radostan English translation Ingenious Poetic Originative Creative Introspective Imaginative Imaginative Versatile Cool blooded Insensitive Without compassion Phlegmatic Even tempered Unirritable Tranquil Placid Cool headed Controlled Stable Self possessed Balanced Relaxed Moderate Happy Unintrusive Cheerful C 0.24 0.04 0.27 0.10 0.27 0.05 0.11 0.17 0.11 0.20 0.05 0.01 0.66 0.28 0.52 0.35 0.64 0.68 0.71 0.66 0.68 0.15 0.44 0.19 0.28 0.14 E 0.61 0.26 0.58 0.62 0.10 0.50 0.64 0.48 0.13 0.02 0.20 0.13 0.01 0.07 0.01 0.17 0.20 0.13 0.17 0.18 0.11 0.54 0.02 0.66 0.16 0.72 A 0.07 0.45 0.07 0.04 0.40 0.09 0.07 0.07 0.00 0.05 0.06 0.24 0.17 0.20 0.42 0.51 0.31 0.28 0.04 0.27 0.17 0.36 0.47 0.24 0.42 0.25 I 0.40 0.34 0.34 0.32 0.30 0.29 0.28 0.15 0.01 0.01 0.00 0.01 0.15 0.07 0.03 0.07 0.12 0.12 0.11 0.10 0.04 0.13 0.05 0.10 0.07 0.17 ES

625

0.03 0.10 0.07 0.12 0.01 0.11 0.14 0.01 0.67 0.62 0.59 0.51 0.13 0.09 0.08 0.08 0.05 0.04 0.00 0.02 0.06 0.07 0.10 0.18 0.19 0.20

Note. The highest factor loading for each variable is marked with an asterisk. Loadings higher than 0.30 are printed in bold. E Extraversion; A Agreeableness; C Conscientiousness; ES Emotional Stability; I Intellect. PL intentional primary loading and SL intentional secondary loading.

replicability analysis using Everett's (1983) method. The results support a solution with a maximum of five replicable factors. When they extract five or less factors, very high replicability coefficients are found, all above 0.95, which is considered to indicate a high level of correspondence among factors or components (Ten Berge, 1986). When more than five factors are extracted, only five of them had replicability coefficients above 0.90, while the others are unreplicable. Following Everett's (1983) criterion, no more than five factors can be considered replicable, i.e. not produced by sampling error. The coefficient alpha reliabilities for the five scales calculated at subjects brand level are 0.91 for Extraversion, 0.89 for Agreeableness, 0.92 for Conscientiousness, 0.82 for Emotional Stability and 0.92 for Intellect. 5. General discussion In general, the authors of this research can conclude from this study that brand personality represents an extensive field for future research. However, many issues need to be resolved. First, the results of this study demonstrate that caution should be exercised when using a single analysis (i.e., subject level, brand level or subject brand level) for drawing conclusions about brand personality structure. In fact, entirely different conclusions can be reached on the basis of a factor analysis performed at different levels of data aggregation. The analysis of betweenbrand variance, similar to the one used by Aaker (1997) indicated that only two components should be retained, both of which,

after the Varimax rotation, are heterogeneous and neither could be assigned an entirely suitable label. The obtained structure showed no resemblance either with the Big-Five model or with the results from previous brand personality studies (Aaker, 1997; Caprara et al., 2001). The component analysis performed at the individual subject level showed much more resemblance with the Big-Five model, but with varying discrepancies depending on the brand that is rated. In general, most of the brands could, according to the Scree plots, be described with less than five dimensions, and the rotated components lack the clarity usually found in human personality description. The brand personality description most frequently omits the dimension of Emotional Stability. While it is obvious that analysis performed at the subject level compared to that performed at the brand level bears more resemblance with the Big-Five structure, the issue of lower variance due to the small number of rated brands, still remains to be addressed. To deal with this problem, the researchers also perform a factor analysis on the subject brand level and, as expected, it produces the five-factor structure that is more aligned with the Big-Five model. Nevertheless, the question remains, what model of analysis optimally captures the concept of brand personality. The study finds that the model using brand means averaged across subjects depicts something similar to public opinion on brands held by the majority of subjects. If the public shares a similar opinion on brands, the correlations at the subject and at the brand level should be similar and the latter analysis would be preferable due to lesser saturation with the measurement error. However, this precondition is usually not

626

G. Milas, B. Mlai / Journal of Business Research 60 (2007) 620626

fulfilled. Individual and public opinion on brands differ more than expected on the basis of simple true score plus error model. Thus, it seems that results based on subjects ratings provide a more accurate portrait of brand personality. Unfortunately, this model is not perfect due to the above-mentioned problem of reduced variance. The study predicts that the factor structure of brand personality corresponds more with the expected Big-Five model if it performs the analysis on a multitude of different brands. The researchers test this model with the factor analysis on subject brand data matrix and the results are consistent with their expectations. Future research should test this hypothesis more rigorously by analyzing a greater number of subjects ratings on a variety of brands. At present, the conclusion is, although ambiguously, that the dimensions of brand personality resemble the Big-Five dimensions of human personality more so than in previous studies (e.g., Aaker et al., 2001; Caprara et al., 2001). Second, two important conclusions can be drawn from this study, as well as from previous research. The first conclusion suggests that brand personality researchers can profit from the development of a brand personality taxonomy. Just as the human personality taxonomists do, brand personality taxonomists can turn back to the dictionary and cull the words that describe individual brand differences. A simple rationale from the lexical approach, All significant individual differences are embodied in language (De Raad, 2000, p.16) can be reformulated into All significant individual brand differences are embodied in language. This kind of analysis might yield descriptors that are more important in the context of brand personality than in the context of human personality. The correspondence of brand personality dimensions derived from the natural language with the ones already obtained from research would provide an important test for the findings and the conclusions reported in previous studies. The second conclusion suggests that brand personality researchers can profit from a development of a valid and reliable instrument for brand personality measurement, perhaps modeled after the IPIP human personality instrument (Goldberg, 2005). If a set of brand personality dimensions is to be developed from the natural language and if one of the recurrent brand personality dimensions is Extraversion, then it would be necessary to adapt short behavior-descriptive sentences in the brand context. Such a common item format can be useful for cross-national personality comparisons of identical brands in the global market, as well as for cross-brand personality comparisons of various brands in particular national markets and further can facilitate scientific communication between brand personality researchers worldwide.

References

Aaker J. Dimensions of brand personality. J Mark Res 1997;24:34756. Aaker JL, Benet-Martinez V, Garolera J. Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: a study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. J Pers Soc Psychol 2001;81:492508. Austin JR, Siguaw JA, Mattila AS. A re-examination of the generalizability of the Aaker brand personality measurement framework. J Strat Mark 2003;11:7792. Azoulay A, Kapferer J-N. Do brand personality scales really measure brand personality? Brand Management 2003;11:14355. Berry JW. On cross-cultural comparability. Int J Psychol 1969;4:11928. Bosnjak M, Bochmann V, Hufschmidt T. Dimensions of brand personality attributions: a person-centric approach in the German cultural context. Unpublished manuscript from the Department of Psychology II, University of Mannheim; 2006. Caprara GV, Perugini M. Personality described by adjectives: generalizability of the Big Five to the Italian lexical context. Eur J Pers 1994;8:35769. Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Guido G. Brand personality: how to make the metaphor fit? J Econ Psychol 2001;22:37795. Cattell RB. The Scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res 1966;1:14061. Church AT, Katigbak MS, Reyes JAS. Further exploration of Filipino personality structure using the lexical approach: do the big-five or bigseven dimensions emerge? Eur J Pers 1998;12:24969. De Raad B. The Big Five personality factors: the psycholexical approach to personality. Gttingen: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers; 2000. Di Blas L, Forzi M. An alternative taxonomic study of personality-descriptive adjectives in the Italian language. Eur J Pers 1998;12:75-101. Digman JM. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997;73:124656. Everett JE. Factor comparability as a means of determining the number of factors and their rotation. Multivariate Behav Res 1983;18:197218. Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am Psychol 1993;48:2634. Goldberg LR. International personality item pool. A Scientific Collaboratory for the Development of Advanced Measures of Personality and Other Individual Differences; 2005. 6 June 2005. 20 April. http://ipip.ori.org/ipip/. Goldberg LR, Rosolack TK. The Big-Five structure as an integrative framework. An empirical comparison with Eysenck's P-E-N model. In: Halverson CG, Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, editors. The Developing Structure of Temperament and Personality from Infancy to Adulthood. New York, NY: Erlbaum; 1994. p. 7-35. Hendriks AAJ, Hofstee WKB, De Raad B. Short behaviour descriptive sentences as units of personality measurement. In: Bermudez J, De Raad B, De Vries J, Prez-Garcia AM, Snchez-Elvira A, Van Heck GL, editors. Personality Psychology in Europe, vol. 6. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1998. p. 4050. Hofstee WB, De Raad B, Goldberg LR. Integration of the Big Five and circumplex approaches to trait structure. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992;63:14663. Mlai B, Ostendorf F. Taxonomy and structure of Croatian personalitydescriptive adjectives. Eur J Pers 2005;19:11752. Ostroff C. Comparing correlations based on individual-level and aggregated data. J Appl Psychol 1993;78:56982. Ten Berge JMF. Rotation to perfect congruence and the cross-validation of component weights across populations. Multivariate Behav Res 1986;21:4164.

You might also like

- Dimensions of Brand PersonalityDocument10 pagesDimensions of Brand PersonalityguillaalmNo ratings yet

- Marine Biofouling (LIBRO)Document316 pagesMarine Biofouling (LIBRO)Laura Alejandra Montaño100% (1)

- Customer: Id Email Password Name Street1 Street2 City State Zip Country Phone TempkeyDocument37 pagesCustomer: Id Email Password Name Street1 Street2 City State Zip Country Phone TempkeyAgus ChandraNo ratings yet

- Brand personality factor based models- A critical reviewDocument8 pagesBrand personality factor based models- A critical reviewIvan MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Brand Identity and ImageDocument12 pagesRelationship Between Brand Identity and ImageLucimari AcostaNo ratings yet

- A Mixed Method Approach To Understanding Brand Personality PDFDocument13 pagesA Mixed Method Approach To Understanding Brand Personality PDFSabina FrățilăNo ratings yet

- Word Marks - A Helpful Tool To Express Your IdentityDocument61 pagesWord Marks - A Helpful Tool To Express Your Identitygabitegi100% (1)

- Consumers' Perceptions of Dimensions of Brand PersonalityDocument14 pagesConsumers' Perceptions of Dimensions of Brand PersonalityHe JiaxinNo ratings yet

- Brand PersonalityDocument9 pagesBrand PersonalityYen Lee KuanNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Brand Identity and ImageDocument12 pagesRelationship of Brand Identity and ImageJulieStanescu100% (1)

- Online Communication of Brand PersonalityDocument19 pagesOnline Communication of Brand PersonalityEllen GordianoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal1 PDFDocument10 pagesJurnal1 PDFJasa Pembuatan Skripsi TesisNo ratings yet

- Consumer Evaluations of Brand Extensions Evidence From IndiaDocument12 pagesConsumer Evaluations of Brand Extensions Evidence From IndiaNaveen OraonNo ratings yet

- Five Dimensions of Brand PersonalityDocument11 pagesFive Dimensions of Brand PersonalityalfareasNo ratings yet

- A Re Examination of The Generalizability of The Aaker Brand Personality Measurement FrameworkDocument17 pagesA Re Examination of The Generalizability of The Aaker Brand Personality Measurement FrameworkMarina KatićNo ratings yet

- A Brand As A Character, A Partner and A Person - Three Perspectives On The Question ofDocument6 pagesA Brand As A Character, A Partner and A Person - Three Perspectives On The Question ofMarina KatićNo ratings yet

- Brands and Branding BDDocument21 pagesBrands and Branding BDveda20No ratings yet

- Dimensions of Brand Personality - Journal of Marketing Research PDFDocument10 pagesDimensions of Brand Personality - Journal of Marketing Research PDFkeerthana gopiNo ratings yet

- Utilizing The CaseDocument19 pagesUtilizing The CaseSaptarshi DattaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Brand Personality On Brand Preference and Loyalty: Empirical Evidence From MalaysiaDocument11 pagesThe Impact of Brand Personality On Brand Preference and Loyalty: Empirical Evidence From MalaysiapersephoniseNo ratings yet

- Brand Identity and Image RelationshipDocument12 pagesBrand Identity and Image RelationshipEkta SawarkarNo ratings yet

- Aaker 1997 Brand PersonalityDocument38 pagesAaker 1997 Brand PersonalityMichelle BuergerNo ratings yet

- Dimensions Brand Personality: Jennifer L. AakerDocument16 pagesDimensions Brand Personality: Jennifer L. AakerDahmane OuslimaniNo ratings yet

- The antecedents and consequences of brand personality future research directioons 2021.Document35 pagesThe antecedents and consequences of brand personality future research directioons 2021.khajiamjad24456No ratings yet

- Separating Brand From Category PersonalityDocument54 pagesSeparating Brand From Category Personalitytrenoops100% (2)

- SEMeSter 4 R.PDocument21 pagesSEMeSter 4 R.PSahil AroraNo ratings yet

- The Origin and Success of Qualitative Research: Lawrence F. BaileyDocument18 pagesThe Origin and Success of Qualitative Research: Lawrence F. BaileyJane PereiraNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of Brand Personality: Developing a Theoretical Framework and Measurement ScaleDocument11 pagesDimensions of Brand Personality: Developing a Theoretical Framework and Measurement ScaleDeep ShreeNo ratings yet

- The Prototypicality of BrandsDocument9 pagesThe Prototypicality of Brandsranjann349No ratings yet

- Aaker (1997), Dimensions of Brand PersonalityDocument11 pagesAaker (1997), Dimensions of Brand PersonalityDWotherspoon22No ratings yet

- Aaker - Jennifer - Dimensions of Brand PersonalityDocument11 pagesAaker - Jennifer - Dimensions of Brand PersonalitySsssNo ratings yet

- Luxury Brand Self-Congruity StudyDocument19 pagesLuxury Brand Self-Congruity StudyBowo BoombaystiexNo ratings yet

- Relevance Versus Convenience in Business Research: The Case of Country-of-Origin Research in MarketingDocument33 pagesRelevance Versus Convenience in Business Research: The Case of Country-of-Origin Research in MarketingAmbreen AtaNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j JDMM 2016 06 011 PDFDocument10 pages10 1016@j JDMM 2016 06 011 PDFLuisa Fernanda Hincapie VelezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Brand IdentityDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Brand Identityc5p0cd99100% (1)

- Literature Review On Internal BrandingDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Internal Brandingafdtbluwq100% (1)

- Das2014 PDFDocument9 pagesDas2014 PDFAdi AlicNo ratings yet

- Am2011 0049 PDFDocument8 pagesAm2011 0049 PDFSHIVANSHUNo ratings yet

- Country of Origin Effects and Consumer Based Brand Equity: July 2000Document6 pagesCountry of Origin Effects and Consumer Based Brand Equity: July 2000Maddy BashaNo ratings yet

- Potential of Brand Personality Attachment Styles As ModeratorDocument9 pagesPotential of Brand Personality Attachment Styles As ModeratorronnyNo ratings yet

- Aaker and Fournier (1995)Document11 pagesAaker and Fournier (1995)Rui ZhangNo ratings yet

- Applicability of Brand Personality Scale in The Indian ContextDocument8 pagesApplicability of Brand Personality Scale in The Indian ContextEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Explaining The Product-Specificity of Count Ry-Of - Origin EffectsDocument32 pagesExplaining The Product-Specificity of Count Ry-Of - Origin EffectsBijuterii Hand MadeNo ratings yet

- Brand IdentityDocument11 pagesBrand IdentitySiarus Sahbiat PriomNo ratings yet

- Antecedents and Consequences of Brand Equity - A Meta-AnalysisDocument24 pagesAntecedents and Consequences of Brand Equity - A Meta-Analysisseema100% (1)

- Celebrity endorsements affect brand personalityDocument31 pagesCelebrity endorsements affect brand personalityyash45goyalNo ratings yet

- The ImpactDocument21 pagesThe ImpactshrestasNo ratings yet

- Mass Prestige Value and Competition BetwDocument13 pagesMass Prestige Value and Competition BetwkittutanmayNo ratings yet

- Branding Places: Applying Brand Personality Concept To CitiesDocument19 pagesBranding Places: Applying Brand Personality Concept To Citiesunbeatable171No ratings yet

- Modelling The Components of The BrandDocument17 pagesModelling The Components of The BrandSuban ManeemoolNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Brand Image PDFDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Brand Image PDFaflsbbesq100% (1)

- Brand Personality How To Make The Metaphor FitDocument20 pagesBrand Personality How To Make The Metaphor FitMario TurchettuNo ratings yet

- Abdullah Naeem - RM ProjectDocument25 pagesAbdullah Naeem - RM ProjectAlif MeemNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On BrandingDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Brandingwzsatbcnd100% (1)

- Investigate The Relationship Between Personality Characteristics and Consumer Behavior - Case Study: Nike BrandDocument8 pagesInvestigate The Relationship Between Personality Characteristics and Consumer Behavior - Case Study: Nike BrandMai Thảo Vy ThiNo ratings yet

- Brand Names That Work AStudyof The Effectivenessof Different Typesof Brand NamesDocument19 pagesBrand Names That Work AStudyof The Effectivenessof Different Typesof Brand NamesAnkit kumarNo ratings yet

- Do Brand Personality Scales Really Measure PersonalityDocument16 pagesDo Brand Personality Scales Really Measure Personalityhenna_guptaNo ratings yet

- 11.what Is A Brand A Perspective On Brand MeaningDocument13 pages11.what Is A Brand A Perspective On Brand MeaningAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Revisiting Aaker's (1997) Brand Personality Dimensions: Validation and ExpansionDocument9 pagesRevisiting Aaker's (1997) Brand Personality Dimensions: Validation and ExpansionPaulinaNo ratings yet

- The Benchmarks Sourcebook: Four Decades of Related ResearchFrom EverandThe Benchmarks Sourcebook: Four Decades of Related ResearchNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Coping: An Inquiry Into Coping With Business UncertaintyFrom EverandLeadership and Coping: An Inquiry Into Coping With Business UncertaintyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Characterization in Compound Semiconductor ProcessingDocument27 pagesCharacterization in Compound Semiconductor ProcessingMomentum PressNo ratings yet

- gr12 15jan19 The Prophetic Methodology in Health Care LessonpDocument3 pagesgr12 15jan19 The Prophetic Methodology in Health Care Lessonpzarah jiyavudeenNo ratings yet

- Automobiles Seat ComfortDocument10 pagesAutomobiles Seat ComfortAnushree DeshingeNo ratings yet

- C 60 A/XF: The Siam Refractory Industry Co.,LtdDocument1 pageC 60 A/XF: The Siam Refractory Industry Co.,LtdGaluhNo ratings yet

- Uop Teuop-Tech-And-More-Air-Separation-Adsorbents-Articlech and More Air Separation Adsorbents ArticleDocument8 pagesUop Teuop-Tech-And-More-Air-Separation-Adsorbents-Articlech and More Air Separation Adsorbents ArticleRoo FaNo ratings yet

- GE Café™ "This Is Really Big" RebateDocument2 pagesGE Café™ "This Is Really Big" RebateKitchens of ColoradoNo ratings yet

- Coaching PhilosophyDocument2 pagesCoaching Philosophyapi-457181424No ratings yet

- G8 - Light& Heat and TemperatureDocument49 pagesG8 - Light& Heat and TemperatureJhen BonNo ratings yet

- Sophiajurgens Resume EdtDocument2 pagesSophiajurgens Resume Edtapi-506489381No ratings yet

- Crankcase Pressure SM019901095211 - en PDFDocument5 pagesCrankcase Pressure SM019901095211 - en PDFDavy GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Quadratic SDocument22 pagesQuadratic SShawn ShibuNo ratings yet

- EXPERIMENT 4B - HOW STRONG IS YOUR CHOCOLATE - Docx - 2014538817Document6 pagesEXPERIMENT 4B - HOW STRONG IS YOUR CHOCOLATE - Docx - 2014538817Shekaina Joy Wansi ManadaoNo ratings yet

- DLP 6 LO2 Safe Disposal of Tools and MaterialsDocument13 pagesDLP 6 LO2 Safe Disposal of Tools and MaterialsReybeth Tahud Hamili - Matus100% (2)

- Ett 531 Motion Visual AnalysisDocument4 pagesEtt 531 Motion Visual Analysisapi-266466498No ratings yet

- ASM Product Opportunity Spreadsheet2Document48 pagesASM Product Opportunity Spreadsheet2Yash SNo ratings yet

- A4931 DatasheetDocument12 pagesA4931 DatasheetDiego HernandezNo ratings yet

- TMF1014 System Analysis & Design Semester 1, 2020/2021 APPENDIX C: Group Assignment Assessment RubricDocument4 pagesTMF1014 System Analysis & Design Semester 1, 2020/2021 APPENDIX C: Group Assignment Assessment RubricWe XaNo ratings yet

- Memo-on-Orientation and Submission of PNPKIDocument5 pagesMemo-on-Orientation and Submission of PNPKICoronia Mermaly LamsenNo ratings yet

- Well Plan Release NotesDocument28 pagesWell Plan Release Notesahmed_497959294No ratings yet

- In2it: A System For Measurement of B-Haemoglobin A1c Manufactured by BIO-RADDocument63 pagesIn2it: A System For Measurement of B-Haemoglobin A1c Manufactured by BIO-RADiq_dianaNo ratings yet

- Sa Sem Iv Assignment 1Document2 pagesSa Sem Iv Assignment 1pravin rathodNo ratings yet

- 07 FSM PDFDocument25 pages07 FSM PDFnew2trackNo ratings yet

- Dyno InstructionsDocument2 pagesDyno InstructionsAlicia CarrNo ratings yet

- 4 1 Separation of VariablesDocument9 pages4 1 Separation of Variablesapi-299265916No ratings yet

- Oven Nordson ElectronicDocument60 pagesOven Nordson ElectronicDanijela KoNo ratings yet

- CSR of DABUR Company..Document7 pagesCSR of DABUR Company..Rupesh kumar mishraNo ratings yet

- MSC Dissertation Gantt ChartDocument6 pagesMSC Dissertation Gantt ChartProfessionalPaperWritingServiceUK100% (1)

- Sheet 5 SolvedDocument4 pagesSheet 5 Solvedshimaa eldakhakhnyNo ratings yet