Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 81.255.71.169 On Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

Uploaded by

JoGuerinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 81.255.71.169 On Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

Uploaded by

JoGuerinCopyright:

Available Formats

Institute for National Strategic Security, National Defense University

Sub-Saharan African Military and Development Activities

Author(s): BIRAME DIOP

Source: PRISM , Vol. 3, No. 1 (12/2011), pp. 87-98

Published by: Institute for National Strategic Security, National Defense University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26469717

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26469717?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Institute for National Strategic Security, National Defense University is collaborating with JSTOR

to digitize, preserve and extend access to PRISM

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

U.S. Air Force (Jeremy T. Lock)

Soldier examines patient during

medical civil action project in Djibouti

Sub-Saharan

African Military

and Development

Activities

By Birame Diop

F

or the last two decades, African states have been facing more internal threats than external

ones. In fact, the African continent is now dealing with ethnic-based conflicts, poverty, health

issues, hunger, and, most recently, radicalization and violent extremism.

In summary, security challenges throughout Africa have evolved in nature and are a lot more

complex. In the health domain, for example, Africa has been decimated by multiple epidemics

and pandemics, notably tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV/AIDS. For HIV/AIDS, sub-Saharan Africa

Colonel Birame Diop, Senegalese Air Force, is seconded as the Director of the African

Institute for Security Sector Transformation based in Dakar.

PRISM 3, no. 1 Features | 87

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

diop

alone is home to more than 22.5 million people human trafficking are increasingly significant

infected with the disease, which is two-thirds of problems. West Africa in particular has become

the total for the entire planet. Not only is the a hub in international drug smuggling. In 2008,

rate of infection high, but the quality of treat- the UN released a report explaining how every

ment has been woefully low. In 2009, 1.3 mil- country in the region is being affected by a

lion Africans died from AIDS, while another highly lucrative cocaine industry. Recent esti-

1.8 million became infected. Even though the mates suggest that $2 billion worth of cocaine

rate of infection has been steadily declining in is being trafficked from South America to

recent years, the situation remains dire, and its Europe through West Africa every year. This is

impact is felt throughout all sectors of African a startling figure when compared with the gross

life, from education and agriculture to the gen- domestic product (GDP) of countries within

eral economic well-being of the African states. the region. Guinea-Bissau, one of the coun-

Well publicized as the AIDS pandemic has tries most deeply affected by drug trafficking,

been, it is not, of course, the only health threat has a GDP of just $304 million.1 The UN notes

facing the continent. High patient-to-doctor that the problem is so severe that it poses the

ratios, poor facilities, and lack of access to med- number one risk to reconstruction in countries

icine are some of the most significant health such as Sierra Leone because of the corruption

concerns, even though new problems are arising invited by such a lucrative trade.2

here and there. Sierra Leone has also become a central

Perhaps the most troubling health threat is player in a growing arms trade on the conti-

the prevalence of counterfeit drug distribution. nent, along with the Democratic Republic of

Throughout West Africa, recent estimates indi- the Congo, Liberia, Somalia, Sudan, and oth-

cate that as much as 40 percent of the prescrip- ers. Estimates place the value of the arms trade

tion medicine for sale is counterfeit. in Africa at $1 billion annually and include

everything from handguns and assault rifles to

rocket-propelled grenades and even antitank

people are abducted, often from and anti-air missiles. In some countries, AK–47

vulnerable places of war or other automatic assault rifles are available for only $6.

hardship, and forced into labor or This trade fuels conflict in many places through-

sexual enslavement out the continent and has contributed to vio-

lence on a dramatic scale. In South Africa, for

Food security is also a major challenge. example, small arms have become the leading

Shortages are commonplace in many areas, cause of unnatural deaths in the country.3 An

and malnutrition runs rampant. Currently, East additional facet of this problem is the increas-

Africa is suffering from a drought that is argu- ing rate of arms trafficking that originates on

ably the worst in 60 years. The United Nations the continent. Some have argued that Eastern

(UN) estimates that 10 to 12 million people are European arms such as the AK–47 no longer

affected and could lose their lives if swift and constitute the bulk of trafficking. They point

bold actions are not taken. instead to a growing arms production industry

The continent is also facing a range of on the continent in countries such as Egypt,

cross-border criminality issues. Drugs, arms, and Nigeria, and South Africa.4

88 | Features PRISM 3, no. 1

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sub-saharan african military and development activities

Unfortunately, cross-border trafficking in militaries, to fight underdevelopment. Failing

Africa has not been limited to commodities to do so could worsen the security situation

such as drugs, fake medicines, and weapons, of the continent for the next several years or

but increasingly involves the smuggling and even decades due to the fact that the major-

enslavement of human beings. These people are ity of African states, as well as their public and

abducted, often from vulnerable places of war or private sectors, have not been able to create the

other hardship, and forced into labor or sexual conditions for sustainable development.

enslavement.5 While at least 130,000 people in

sub-Saharan Africa alone have been captured State, Public, and Private

and exploited in this manner, the UN Office on Sectors Cannot Solve the

Drugs and Crime argues that few countries on Problems Independently

the continent have begun to adopt measures to

address the problem.6 The lives of millions of Africans are

The increase in various forms of traf- being threatened daily by security challenges.

ficking in Africa points to a larger and more Unfortunately, African states and the sec-

endemic problem. Organized crime in general, tors that have typically been charged with

and terrorism in particular, has become a seri- addressing these challenges are not working

ous matter. The Mombasa region of Kenya and together. Whether due to operational failures

neighboring Somalia have long struggled with or resource limitations, these parties have sim-

connections to Middle East terrorist organiza- ply not been able to solve the challenges inde-

tions such as al Qaeda. However, this problem pendently, and the gap between the needs and

has now spread to other regions of the conti- what the states and sectors are able to provide

nent. Nigeria, for instance, has seen a recent is too wide for the situation to greatly improve

increase in attacks from the radical group Boko in the near future.

Haram, which has devastated the security in After more than 50 years of independence,

much of the country. The radical group has also many African states are still relatively weak. In

claimed responsibility for the attack on a UN fact, the majority are largely dependent on for-

office in Abuja that killed more than 20 people eign aid, with a large percentage of their budgets

in August 2011. Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and emanating from the international community.

Chad are also facing terrorist activities with the African states are indeed struggling with limited

presence of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. resources while their challenges are exponen-

This list of new challenges facing the con- tially increasing. The World Bank’s most recent

tinent is unfortunately far from exhaustive. publication of Africa Development Indicators

Africa is facing several other security concerns highlighted the increasingly abstract nature of

such as high rates of infant mortality, urban issues facing the continent. Using the phrase

violence related to youth unemployment and quiet corruption, the World Bank explored a

overpopulation, desert advancement, political range of issues facing African development that

divergences, and corruption. are less overt than well-publicized incidences

African states need to find ways to confront of so-called big-time corruption; nonetheless,

these serious threats directly and more effi- all of these issues are severely undermining the

ciently, but also to mobilize resources, including continent’s development potential.

PRISM 3, no. 1 Features | 89

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

diop

The World Bank defines this quiet corrup- of the entire FDI in underdeveloped countries

tion as occurring “when public servants fail to and decreased by 9 percent in 2010.

deliver services or inputs that have been paid This conundrum highlights the nature of

for by the government.” The bank highlights a many of the problems now facing Africa. The

number of examples from a wide range of areas problems and solutions are often too intricately

within the public sector. The Africa Development connected for the situation to improve without

Indicators report explains that in several African outside assistance. Furthermore, many of these

countries, between 15 and 25 percent of salaried challenges have a compounding effect: they

school teachers are not showing up for work. worsen over time as they go unaddressed. Thus,

This also holds true for doctor absenteeism from rather than improving, the situation is likely to

primary care facilities. The bank further notes worsen and place more strain on the sectors that

that a high percentage of the fertilizer avail- are already unable to keep up. There exists a

able to farms is diluted of the nutrients that it is gap between the needs of the population and

intended to supply. This can have severe conse- the resources that states and public and private

quences on a region that already faces perennial sectors are able to provide.

food shortages. The most important response to this situa-

tion is to improve states’ capacities and invest

in the public and private sectors in order to

all sectors of African society need to build capacity to fulfill societal roles in the

work collaboratively to begin solving future. In the meantime, however, filling the

these problems gap that currently exists requires a response

that uses all available resources. All sectors of

African society need to work collaboratively to

In addition to these shortcomings of begin solving these problems; it is simply not

states and their administrations, the African responsible to allow any available resources to

private sector is simply too stunted to fill go unused while people are suffering.

the gap needed to provide the services and During times of peace, African militar-

employment. Though lack of education con- ies have a great many resources available to

tinues to be a major problem, students who them that can be used to help address many

are able to complete a high school education of the challenges already outlined. Among

or achieve higher degrees are often unable to other things, they have planes for delivering

find employment. The continent is thus stuck the food, medicine, and doctors needed to

in a serious catch-22. The private sector, for fight health problems, as well as manpower

example, needs more educated people so it can and expertise to assist in building infrastruc-

grow and develop, but cannot provide these ture. When available, these resources must be

people with jobs until after it gains strength. used to contribute to the positive development

Unfortunately, it is not gaining strength in of the continent and to save lives. In certain

many African countries due to lack of state countries such as South Sudan and Zimbabwe,

assistance as well as insufficient and decreasing the situation in the public and private sectors

foreign direct investment (FDI). In fact, FDI is so delicate that for several years to come,

in Africa represents no more than 10 percent the military will remain the only functioning

90 | Features PRISM 3, no. 1

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sub-saharan african military and development activities

organization capable of dealing with certain constituents could keep mobilizing the military

national challenges. as an easy answer rather than investing time

While it is clear that militaries in sub- and resources in the other sectors. Overreliance

Saharan Africa have a role to play to improve on the military can lead to the withering of the

the situation, many African observers are not public and private sectors rather than helping

in favor of the inclusion of military personnel them to gain the strength to eventually be the

in development activities and would prefer that sustainable solution.

they intervene only in emergency situations. Third, this reliance on the military can

The reasons these observers invoke are many. lead to its intrusion into state politics. As the

military gains power within the domestic sphere

Perceived Risks of Mobilizing with politicians—and as populations increas-

the Military ingly depend on it to provide needed services—

Despite the reality that the public and it can manipulate this dependence in order

private sectors are struggling and often fail- to serve its own interests. Civilians and their

ing to provide required services, some of the elected leaders run the risk of losing control of

resources available to the military to assist the military, in whole or in part.

in this situation are often unused because, at Unfortunately, fear of these risks does not

least in part, academics and members of civil rest in the theoretical realm. Instead, it is well

society have warned against augmenting the grounded in the history of the African continent.

military role especially in domestic matters. Even a brief look at the history of many of the

They argue that to do so exposes the civilian militaries in Africa reveals the potential conse-

population, state, and possibly even the con- quences of a powerful and uncontrollable military.

tinent to a variety of risks. Since independence movements began

First, they argue that the military is meant in 1956, coups have been a constant prob-

to address traditional security challenges to state lem throughout Africa. In less than 50 years,

sovereignty. Expanding their role to deal with African countries saw an astonishing 80 suc-

more abstract issues, especially those within cessful coups, to say nothing of nearly 250 addi-

domestic politics, is simply not what the mili- tional coup attempts or plots.7 This trend has

tary is intended for. Doing so detracts from the continued throughout the start of the 21st cen-

military’s main operational goal of protecting tury, with an additional six successful coups in

the state. the first 8 years of the new millennium.8 Recent

Second, and perhaps more prominently, events in Burkina Faso and Guinea further

scholars and members of African civil society highlight the continuing instability of some of

argue that allowing the military to play a role Africa’s security sectors.

in a broader range on nontraditional tasks can While the highest numbers of coups have

lead to the “militarization” of society. Due to been in Francophone West Africa, the problem

the relative strength of the military when com- has not been confined to any one region. Most

pared with African public and private sectors, countries of the continent have been victims of

it can quickly become a dominating force when coups. Indeed, a full 30 sub-Saharan African coun-

it enters these other domains. Politicians look- tries were victims of successful coups by 2001, and

ing for quick solutions to the grievances of their another 11 experienced unsuccessful attempts.

PRISM 3, no. 1 Features | 91

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

diop

Somali woman hands malnourished

child to African Union Mission in

Somalia medical officer for care

UN (Stuart Price)

The effects of these successful and attempted coups reach beyond the physical damage and loss of life

that often accompanies them. The destabilizing effect of a coup impairs a country’s economic develop-

ment as domestic infrastructure is disturbed and international actors become hesitant to invest. A coup

or coup attempt often impairs a country for many years following the cessation of violence.

Of course, coups are far from being the only problem caused by some African security sectors.

Human rights abuses by many militaries have been well documented. Many of these forces have

been implicated in pillaging, rape, mutilation, and other forms of torture as well as in murder and

genocide. Dictatorial regimes in the Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia, Liberia, Nigeria

South Africa, Uganda, and Zaire have used their militaries to undertake all kinds of atrocities

against their people. The hesitation of many to see the role of the military expanded in any fashion

is understandable. On the other hand, perhaps it is more helpful to conceive the assistance of the

military in nontraditional, development-type activities as a change in rather than an expansion of

the military’s role. By creating programs from this perspective, changing the practices of the military

and its relationship with the civilian population can be an integral part of project design. Given the

benefits (outlined below), it is simply too critical not to use the resources available to the military to

alleviate suffering on the continent and move African countries toward sustainable development.

Mobilizing the Military

Countries such as the United States, even though they recognize that the military is not

the most efficient organization to undertake certain categories of activity, plan to call upon their

92 | Features PRISM 3, no. 1

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sub-saharan african military and development activities

militaries when agencies are not capable of recently, but up until now, most of this capac-

gathering necessary resources. For instance, ity often remains inadequately used during

Department of Defense Directive 3000.05, times of peace. Failing to use these resources

dated November 2005, states that the U.S. means that illnesses go untreated, and people

military is ultimately responsible to prosecute lose their lives.

missions when agencies are not able to do so. Apart from health challenges, Africa is

Regarding food security, corruption, and facing serious youth unemployment. Figures

health issues, the role for the military may often highlight the fact that 70 percent of the

not be immediately evident. Ideally, address- continent’s population is under the age of 25.

ing these challenges means empowering public Unfortunately, the same figures underline the

and private entities that are already tasked with fact that these young Africans represent no

solving these problems. Unfortunately, for a more than 25 percent of the active population.

variety of reasons, the sectors that are supposed Youth idleness is far from being the only

to address these concerns have been unable to potential risk of unrest throughout the conti-

adequately do so. This might be due to the quiet nent but undoubtedly represents an important

corruption noted by the World Bank, or it might factor that can contribute, under certain cir-

simply be the result of insufficient resources or cumstances, to instability and insecurity. The

lack of expertise and will. Whatever the rea- military, while being the major employer of the

son, it is clear that additional measures must be public sector in many African states, is limited

taken to address the gap between what is cur- in terms of job provision. Nonetheless, it can

rently being done and what needs to be done for participate in the civic education of the youth

African states to stabilize and prosper. many observers consider the most vulnerable

Mobilizing the military to become group in African societies.

involved in this new range of societal chal-

lenges is not meant to replace or circumvent

other sectors. On the contrary, using the youth idleness is far from being the only

resources already available to the military can potential risk of unrest throughout the

alleviate pressure from other entities while continent but undoubtedly represents an

they reform and develop new strategies and important factor that can contribute to

capacities. For reform of these sectors to take instability and insecurity

place in a realistic and effective manner, care-

ful planning over time is needed. The military

can lighten the strain placed on these other Africa, like the other continents, is expe-

groups during this period. riencing frequent natural disasters due to cli-

In terms of health care, African coun- mate change, such as flooding, coastal erosion,

tries nearly uniformly suffer from inadequate desert advancement, and so forth. Typically

health facilities and an insufficient num- well organized, relatively easy to mobilize,

ber of doctors. The military in many coun- and disciplined, militaries can play a crucial

tries possesses the capacities necessary to at role in states’ efforts to tackle these issues effi-

least begin addressing this problem. In many ciently. Militaries can also be mobilized to fight

countries, important efforts have been made the increasing number of wildfires across the

PRISM 3, no. 1 Features | 93

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

diop

continent as well as the alarming deforestation established and safeguards need to be put

witnessed lately. into place. Furthermore, especially in coun-

Drought is currently devastating people tries where serious violations of human rights

throughout eastern Africa. More than 10 million have been perpetrated by the military, recon-

people are affected by what has become perhaps ciliation must take place and trust must be

the worst drought in more than 60 years. Rather built. Trust can only be built if the military

than waiting for the international community to communicates effectively and regularly with

send assistance—while lives are lost—militaries the population. Even during crisis periods,

across the region and perhaps even the continent the military ought to behave in a respectful,

as a whole could have been mobilized to begin responsible, and professional way in order to

relieving the strain caused by the food shortage.9 avoid deliberate violations of human rights.

Finally, African countries are badly lack- The needs and interests of all relevant stake-

ing sound infrastructures. Most of the conti- holders must be taken into consideration

nent’s infrastructure, if it even existed, has been when creating these safeguards, ensuring that

destroyed by years of conflict. African militaries the military serves to supplement rather than

could help states in their efforts to build or reha- replace the sectors traditionally charged with

bilitate infrastructures. responding to these challenges.

In reality, mobilizing the military in this man- In pursuing this mobilization goal, the

ner and in these different domains benefits civil- essential element that can help ensure success

ian populations, the sectors that generally provide is maintaining civilian oversight of the military

these services, and the military itself. It allows the and its projects. Doing so begins with clearly

military and its resources to remain more consis- defining the military’s new role as temporary

tently active while allowing the traditional public and supplemental to the public and private sec-

and private sectors to reform in a more controlled tors. Projects should be designed in such a way

environment instead of constantly operating that it is always clear that the military is not

under crisis or emergency conditions. taking over or dominating but rather is assisting

These benefits can be found in a consis- the other sectors and alleviating the pressure

tent list of other areas as well. This list, even being placed on them. Having a clearly defined

though not extensive, reveals the importance timetable for a military’s assistance will help

of utilizing the resources of the military to help demonstrate the temporary nature of its work,

address the challenges now facing the conti- so other sectors do not become overly reliant

nent. However, given the risks noted above, it on it.

is clear that careful planning will be critical if Realizing this oversight and creating the

military mobilization is to be done in a way that environment for these expectations require the

realizes these benefits, instead of tragically fall- development of a legal framework for imple-

ing victim to the risks. mentation. The circumstances in which the

military can be mobilized to deal with nontra-

Creating Safeguards ditional security concerns need to be clearly

If militaries are to be mobilized to assist outlined in the states’ national security policies

in addressing the challenges now facing much and in law. In some cases, it might even make

of Africa, then clear expectations need to be sense to cement these conditions within the

94 | Features PRISM 3, no. 1

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sub-saharan african military and development activities

framework of the state constitution in order to While it is beyond the scope of this article

broadcast the expectations of both the military to examine each of these cases in depth, it is

and general population. helpful to look at the Senegalese experience to

Creating these safeguards is not entirely illustrate the possibilities of limited and con-

a novel concept. Efforts have been made trolled mobilization of African militaries to deal

over the past 20 years by those in charge of with nontraditional challenges.

security sector reform to improve military

practices. Thus, even if reforms have been Senegal’s Armée-Nation

more focused than the proposed initiatives, In Senegal, the military has been success-

they have enjoyed varying degrees of success. fully mobilized to assist the country in a wide

Lessons can be learned to help shape the nec- range of activities, paying particular attention

essary framework that ensures the military is to issues directly related to development. The

mobilized in a manner that is beneficial to the list of areas in which the military has helped is

state and its population. long: health, infrastructure development, agri-

In addition to the lessons learned from culture, education, border management, and

security sector reform processes, there are environmental protection, among others.

recent examples in Africa that highlight the The projects the Senegalese military partici-

potential for military mobilization in a supple- pates in are selected specifically for their ability

mentary fashion. These examples are of par- to help the general population. The military pro-

ticular importance because they demonstrate vides immediate and tangible assistance to the

that this proposition is not merely a theoreti- people and participates in projects with a lon-

cal possibility, but a reality that has already ger term focus such as helping in infrastructure

seen some success. In Kenya, for example, the

military and civil society have collaborated

on environmental issues in a program that

lessons can be learned to help shape the

produced the concept of the “environmental

necessary framework that ensures the

soldier.” This program clearly participated in

military is mobilized in a manner that is

strengthening the national and international beneficial to the state and its population

image of Wangari Maathai, an environmental

and political activist. Maathai later became construction and disease prevention programs.

the first African woman to win the Nobel Up to 80 percent of the curative activities

Peace Prize for her work. In Guinea, now that undertaken by the military health services are

the new democratically elected government for civilian populations. The Senegalese mili-

is in place, the military has been called on to tary, along with the services of the ministry

help fix damaged bridges and roads through- of environment and conservation, is actively

out the country. In Burkina Faso, South Africa, participating in the realization of the country’s

and Botswana, the military has worked collab- portion of the 7,000-kilometer great green wall

oratively on civic education programs, and in that African states are committed to build to

Senegal, there are many examples of how the stop desert advancement.

military has been successfully mobilized in a In addition to the benefits of these pro-

complementary way. grams for the Senegalese civilian population,

PRISM 3, no. 1 Features | 95

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

diop

the military itself and the state as a whole over Africa looking to Senegal for an example

receive indirect benefits from these nontra- of how to improve their militaries.

ditional activities. In part by participating in If the reasons for Senegal’s successful expe-

such projects, the military enjoys a better repu- rience are many and diverse, the one most

tation within Senegal than most African mili- invoked is the creation and implementation

taries have in their respective countries. This of the concept Armée-Nation. In fact, the

increased trust helps the military remain con- meeting between President Senghor and the

nected with the general population and receive country’s second chief of defense staff, General

support, and thus be better informed of security Jean Alfred Diallo, determined the Senegalese

concerns. The state, for its part, greatly ben- experience. President Senghor was known as

efits from the work the military does in building a peaceful leader with a clear vision for the

cross-sector relationships. For example, with the country’s future, and General Diallo, a former

officer in the French army corps of engineers,

was known as a builder. Together, they have

the United States and most European helped develop the concept Armée-Nation that

countries, as well as emerging powers has been, since the early years of independence,

such as China, Russia, and Brazil, are the backbone of the military’s participation in

facing acute difficulties that might development activities. The Armée-Nation

prevent them from supporting Africa is well known and appreciated by the civilian

population and widely studied in the military.

Of course, while this example has been

border management commission run by the mil- largely successful and offers hope for using the

itary but composed of members from all sectors military in nontraditional activities, there is

of the society, Senegal has been able to promote still room for improvement. Most significantly,

peaceful relations at certain parts of its borders Senegal could work more closely on the estab-

with neighboring countries and thus needs to lishment of the formal legal framework sug-

deploy fewer security forces to these regions, gested earlier and on clearer planning, program-

therefore saving a great deal of resources. ming, and coordinating processes. In this regard,

In addition to the above benefits, some the creation in the late 1990s of a civil-military

scholars consider these nontraditional activities committee was an important initiative that

undertaken by the Senegalese military as a key needs to be reconsidered.

reason for the country’s stability. West Africa To continue to involve the military in

has been one of the most unstable regions in development activities while avoiding the

the world with many coups and human rights militarization of society, leaders of civil society,

abuses. Senegal, however, has been an excep- the military, executive, judiciary, and legisla-

tion in the region, enjoying stability and peace- ture need to work together on creating the right

ful political transitions since independence in conditions for the military’s projects, notably

1960. Many argue that the country’s first presi- an efficient communication strategy, a good

dent, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was a major factor financing mechanism, and measures that guar-

for stability. This success is beginning to gain antee discretion. That is important not only for

international attention with other countries all Senegal, but also for other countries that seek

96 | Features PRISM 3, no. 1

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sub-saharan african military and development activities

to emulate the Senegalese experience and in which the military does not have such a strong history

of good practices.

Conclusion

Since the end of the Cold War, the security situation in Africa has evolved, and new nontradi-

tional security challenges have emerged. In reality, the African continent is currently dealing with

poverty, health issues, political-based crises, ethnic-based conflicts, food shortages, natural disasters,

and radicalization. African states in general, and specifically their public administrations and private

sectors, have not been able to cope with these complex security concerns. This situation is not likely

to end soon given the fact that the world is facing serious economic crises that are having a negative

impact on the continent.

The United States and most European countries, as well as emerging powers such as China,

Russia, and Brazil, are facing acute difficulties that might prevent them from supporting Africa. The

continent should therefore mobilize all of its available resources to confront these new challenges.

The military also needs to be mobilized to deal with these nontraditional security concerns by con-

tributing its resources whenever possible.

Of course, doing so is not without challenges, particularly on a continent that has experienced

so many negative events as a result of the military. By carefully planning and putting the neces-

sary safeguards in place, however, military assistance is largely possible and beneficial to society.

Furthermore, using the military could help improve the relationship between the military and civil-

ians and ultimately bolster greater cooperation among the various sectors of African society. Several

countries have successfully involved their militaries in meeting the new challenges. Among them,

the most noticeable are Botswana, Burkina Faso, Kenya, Senegal, and South Africa.

Senegal, though not a perfect example, is often cited as one of the most successful cases in sub-

Saharan Africa. The country has been able to keep its military professional and useful to Senegalese

society. Many observers of the African security sector consider strong Senegalese civilian and mili-

tary leadership in the early days of independence as the major factor. To continue its success,

Senegal needs to work on a formal legal framework and focus on better planning, programming,

and coordination mechanisms.

The Senegalese experience, and its concept Armée-Nation, cannot be exported everywhere in

Africa, but it can undoubtedly inspire many African countries that are interested in involving their

militaries in development activities. PRISM

Notes

1

United Nations (UN), “West Africa Drug Trade: New Transit Hub for Cocaine Trafficking Fuels

Corruption,” 2008, available at <www.un.org/en/events/tenstories/08/westafrica.shtml>.

2

UN, “International Drug Trafficking Poses Biggest Threat to Sierra-Leone, UN Warns,” February 3, 2009.

3

Matt Schroeder and Guy Lamb, “The Illicit Arms Trade in Africa: A Global Enterprise,” African Analyst

3, no. 1 (2006), 69–78.

4

Eric G. Berman, “Illicit Trafficking of Small Arms in Africa: Increasingly a Home-Grown Problem,”

presentation in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, March 14, 2007.

PRISM 3, no. 1 Features | 97

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

diop

5

UN Office on Drugs and Crime, “Human Trafficking and Eastern Africa.”

6

Ibid.

7

Patrick J. McGowan, “African Military coups d’état, 1956–2001: Frequency, Trends and Distribution,”

The Journal of Modern African Studies 41, no. 3 (2003), 339–370.

8

David Zounmenou, “Coups d’état in Africa between 1958 and 2008,” adapted from Issaka K. Souaré,

Civil Wars and Coups d’Etat in West Africa: An Attempt to Understand the Roots and Prescribe Possible Solutions

(Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2006).

9

“Somalis Displaced by Drought Hit by Mogadishu Rains,” BBC News, July 15, 2011, available at <www.

bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14165509>.

98 | Features PRISM 3, no. 1

This content downloaded from

81.255.71.169 on Fri, 27 May 2022 10:58:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Giant Guardian Generation 1.81Document194 pagesGiant Guardian Generation 1.81Paula Sebastiao100% (3)

- President Cereal Project RubricDocument3 pagesPresident Cereal Project Rubricapi-266941933No ratings yet

- War Despatches Indopak Conflict 1965Document22 pagesWar Despatches Indopak Conflict 1965kapsicum0% (1)

- A Military Diplomacy A Tool To Pursue Foreign PolicyDocument16 pagesA Military Diplomacy A Tool To Pursue Foreign PolicyPokli PuskersinNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Domestic AffairsDocument5 pagesPakistan Domestic AffairsArsalan Khan GhauriNo ratings yet

- The Climate Risks We FaceDocument42 pagesThe Climate Risks We FaceBranko Brkic50% (2)

- The Impact of COVID 19 On The Growing North South DivideDocument9 pagesThe Impact of COVID 19 On The Growing North South Divideსო ფიაNo ratings yet

- African security in the twenty-first century: Challenges and opportunitiesFrom EverandAfrican security in the twenty-first century: Challenges and opportunitiesNo ratings yet

- NTEC 2023 Final Submission.Document7 pagesNTEC 2023 Final Submission.Merciful NwaforNo ratings yet

- Human Security and Developmental CrisisDocument13 pagesHuman Security and Developmental CrisispauriudavetsNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 81.255.71.169 On Fri, 27 May 2022 10:51:38 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 81.255.71.169 On Fri, 27 May 2022 10:51:38 UTCJoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Sani Tanimu AbdussalamDocument4 pagesSani Tanimu AbdussalamNURA MAGAJI MOHDNo ratings yet

- DB82 Part16Document5 pagesDB82 Part16Ceres Styx KvinnaNo ratings yet

- CRS - RL33584 - AIDS in AfricaDocument31 pagesCRS - RL33584 - AIDS in AfricabowssenNo ratings yet

- My ProposalDocument10 pagesMy Proposalosrian kargboNo ratings yet

- GEOPOLL COVID Report April 15 2020Document15 pagesGEOPOLL COVID Report April 15 2020The Independent MagazineNo ratings yet

- Africa's Missing BillionsDocument38 pagesAfrica's Missing BillionsControl ArmsNo ratings yet

- Editorial: The LancetDocument1 pageEditorial: The Lancetkayegi8666No ratings yet

- Transnational Insurgencyand Border Security Challengesin Lake Chad Basin The Nigerian PerspectiveDocument22 pagesTransnational Insurgencyand Border Security Challengesin Lake Chad Basin The Nigerian Perspectiveumar muhammadNo ratings yet

- U.S. Strategy Toward Sub Saharan Africa FINAL Aug2022Document17 pagesU.S. Strategy Toward Sub Saharan Africa FINAL Aug2022Ganyobi BionicNo ratings yet

- WFP 0000113974Document13 pagesWFP 0000113974Mohamed MetwallyNo ratings yet

- Infectious Diseases in Africa: Using Science To Fight The Evolving ThreatDocument14 pagesInfectious Diseases in Africa: Using Science To Fight The Evolving ThreatAhmed Ali Mohammed AlbashirNo ratings yet

- Article: Proposed Strategies For Easing COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in AfricaDocument12 pagesArticle: Proposed Strategies For Easing COVID-19 Lockdown Measures in AfricaMvelako StoryNo ratings yet

- Coup De'eter NigerDocument28 pagesCoup De'eter NigerLouis EdetNo ratings yet

- How-the-COVID-19-crisis-may-affect-electronic Payments-In-AfricaDocument11 pagesHow-the-COVID-19-crisis-may-affect-electronic Payments-In-AfricabasseyNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 in Africa: Contextualizing Impacts, Responses, and ProspectsDocument12 pagesCOVID-19 in Africa: Contextualizing Impacts, Responses, and ProspectsKesner RemyNo ratings yet

- Violent Extremism in West Africa Are Current Responses EnoughDocument8 pagesViolent Extremism in West Africa Are Current Responses EnoughThe Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- Writing SampleDocument16 pagesWriting Samplekapinga87No ratings yet

- A Short Analysis On The Effect of The RussianDocument3 pagesA Short Analysis On The Effect of The RussianDonsonNo ratings yet

- Data Are Needed Whenever We Take Studies or Researches. They Are Used To Undertake ParticularDocument10 pagesData Are Needed Whenever We Take Studies or Researches. They Are Used To Undertake ParticularKobayashii InoNo ratings yet

- MAA6200109p PDFDocument18 pagesMAA6200109p PDFLAITON MWAKHATALANo ratings yet

- CRS - RL32489 - Africa: Development Issues and Policy OptionsDocument44 pagesCRS - RL32489 - Africa: Development Issues and Policy OptionsbowssenNo ratings yet

- Report of IbDocument31 pagesReport of IbThủy Lê Thị BíchNo ratings yet

- General Assembly: United NationsDocument24 pagesGeneral Assembly: United NationsJordan PopovskiNo ratings yet

- Fagha Project Chapter 1-5Document49 pagesFagha Project Chapter 1-5ajuguisrael6No ratings yet

- House Hearing, 113TH Congress - The U.S. Contribution To The Fight Against MalariaDocument75 pagesHouse Hearing, 113TH Congress - The U.S. Contribution To The Fight Against MalariaScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- FTQ May 2019Document6 pagesFTQ May 2019Anh PhạmNo ratings yet

- T.absoluta Page12Document60 pagesT.absoluta Page12AssefaTayachewNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proofs: Research in GlobalizationDocument35 pagesJournal Pre-Proofs: Research in GlobalizationMohammed Shuaib AhmedNo ratings yet

- GBMT1009 W23 - G20 AssignmentDocument5 pagesGBMT1009 W23 - G20 AssignmentBLESSING BANDANo ratings yet

- AFRICOM Related News Clips 22 April 2011Document20 pagesAFRICOM Related News Clips 22 April 2011U.s. Africa CommandNo ratings yet

- 2014 Korotayev Africa DemographyDocument10 pages2014 Korotayev Africa DemographygiperbolaNo ratings yet

- NSTP National SecurityDocument26 pagesNSTP National Securityangelynjoyce00No ratings yet

- Feature: Small But Tenacious: South Africa's Health Biotech SectorDocument19 pagesFeature: Small But Tenacious: South Africa's Health Biotech SectorRollins JohnNo ratings yet

- The Contemporar y World: Countries ReasonsDocument3 pagesThe Contemporar y World: Countries Reasonsravelyn bresNo ratings yet

- Global Insecurity and Its Aftermaths: Nigeria at 2011Document6 pagesGlobal Insecurity and Its Aftermaths: Nigeria at 2011A A AdedejiNo ratings yet

- Small Armsand Light Weapons Proliferationand Its Implicationfor West African Regional SecurityDocument11 pagesSmall Armsand Light Weapons Proliferationand Its Implicationfor West African Regional SecurityOnyigbuo StephenNo ratings yet

- UN Transnational Organized Crime in West Africa, A Threat Assessment (2013) Uploaded by Richard J. CampbellDocument68 pagesUN Transnational Organized Crime in West Africa, A Threat Assessment (2013) Uploaded by Richard J. CampbellRichard J. Campbell https://twitter.com/No ratings yet

- South Africa's War Against Malaria: Lessons For The Developing World, Cato Policy Analysis No. 513Document20 pagesSouth Africa's War Against Malaria: Lessons For The Developing World, Cato Policy Analysis No. 513Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- African ProblemsDocument8 pagesAfrican ProblemsDavid OpondoNo ratings yet

- Malaria in 2002Document3 pagesMalaria in 2002Musa LandeNo ratings yet

- Gen Townsend Us AfricomDocument19 pagesGen Townsend Us Africomnelson duringNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 in Africa - v4Document16 pagesCOVID-19 in Africa - v4Ali AmarNo ratings yet

- Socio Economic Impacts of Emerging Infectious Diseases in AfricaDocument11 pagesSocio Economic Impacts of Emerging Infectious Diseases in AfricaGreater K. OYEJOBINo ratings yet

- Covid Africa Article, 04dec20Document1 pageCovid Africa Article, 04dec20Natalie WaqarNo ratings yet

- The Southern African Development Community: Regional Renaissance? Security in A Globalized WorldDocument17 pagesThe Southern African Development Community: Regional Renaissance? Security in A Globalized WorldTino MarcosNo ratings yet

- CRS - RL30883 - Africa: Scaling Up The Response To The HIV/AIDS PandemicDocument26 pagesCRS - RL30883 - Africa: Scaling Up The Response To The HIV/AIDS PandemicbowssenNo ratings yet

- Consolidation of Financial InstitutionsDocument2 pagesConsolidation of Financial InstitutionsPatricia SorianoNo ratings yet

- AERC Special Call For Proposals Group E August 2023Document10 pagesAERC Special Call For Proposals Group E August 2023Percival KufamusariraNo ratings yet

- 2019 12 18 Vanishing Herds Research Paper 10Document20 pages2019 12 18 Vanishing Herds Research Paper 10Elian KipNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Peacebuilding in Africa - ACCORDDocument11 pagesChallenges of Peacebuilding in Africa - ACCORDTesfaye MekonenNo ratings yet

- Policy Brief: Public Trust, Capacity And: Early Lessons From AfricaDocument8 pagesPolicy Brief: Public Trust, Capacity And: Early Lessons From AfricaElamrani KarimNo ratings yet

- Opinion: An Appeal For Large Scale Production of Antiretroviral Drugs in AfricaDocument4 pagesOpinion: An Appeal For Large Scale Production of Antiretroviral Drugs in AfricaSyed Sheraz AliNo ratings yet

- Security Council: United NationsDocument17 pagesSecurity Council: United Nationsbeniamino79No ratings yet

- Plant Science, Agriculture, and Forestry in Africa South of the Sahara: With a Special Guide for Liberia and West AfricaFrom EverandPlant Science, Agriculture, and Forestry in Africa South of the Sahara: With a Special Guide for Liberia and West AfricaNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 27Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 27JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 23Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 23JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 18Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 18JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 15Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 15JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 26Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 26JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 43Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 43JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 20Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 20JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 11Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 11JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 46Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 46JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 28Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 28JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 3Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 3JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Guide-To-Neverwinter 7Document1 pageGuide-To-Neverwinter 7JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Menaces-sur-Port-Nyanzaru 1Document1 pageMenaces-sur-Port-Nyanzaru 1JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Ukraine Support Tracker Release 13Document1,513 pagesUkraine Support Tracker Release 13JoGuerinNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 81.255.71.169 On Fri, 27 May 2022 10:51:51 UTCDocument21 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 81.255.71.169 On Fri, 27 May 2022 10:51:51 UTCJoGuerinNo ratings yet

- Chainmail QRSDocument2 pagesChainmail QRSNickNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Jaga IgdDocument9 pagesJadwal Jaga IgdsasaqiNo ratings yet

- Russia Invades Ukraine Group ActivityDocument2 pagesRussia Invades Ukraine Group Activityapi-594076818No ratings yet

- DrakasDocument208 pagesDrakasketch117No ratings yet

- Overtime: Cassidy Byars 88Document3 pagesOvertime: Cassidy Byars 88Jarrett FarrellNo ratings yet

- Sci-Fi Novel 1Document1 pageSci-Fi Novel 1Bailey ThorsonNo ratings yet

- Awaiting The Allies' Return (Villanueva Dissertation) (FINAL DRAFT) (04 FEB 2019)Document276 pagesAwaiting The Allies' Return (Villanueva Dissertation) (FINAL DRAFT) (04 FEB 2019)Jessa CordeNo ratings yet

- Imcc 2022 - Moot PropositionDocument9 pagesImcc 2022 - Moot Propositionjessika bhowmikNo ratings yet

- Cmis2012: Tra C U Hóa ĐơnDocument19 pagesCmis2012: Tra C U Hóa ĐơnPhạm Hữu TrúcNo ratings yet

- The Ether Drake: LeviathanDocument2 pagesThe Ether Drake: LeviathanhniqvcaurxnwiakuowNo ratings yet

- The Military Balance 2000 PDFDocument319 pagesThe Military Balance 2000 PDFAlex GomezNo ratings yet

- Office 2013 Pro Plus Activation Keys (Retail & Mak)Document4 pagesOffice 2013 Pro Plus Activation Keys (Retail & Mak)Eduardo Perez60% (5)

- Survey Harian Rawat Jalan (BLM Fiks)Document69 pagesSurvey Harian Rawat Jalan (BLM Fiks)Slamet FujioNo ratings yet

- Rand Pea1157-1Document16 pagesRand Pea1157-1John TranNo ratings yet

- Resident Evil Collectables ListDocument2 pagesResident Evil Collectables Listicecup lavabucketNo ratings yet

- +1 Zoology-Study-Material-Tamil-Medium Header2Document14 pages+1 Zoology-Study-Material-Tamil-Medium Header2parirNo ratings yet

- MED147 Exercise 4Document4 pagesMED147 Exercise 4Haze YueNo ratings yet

- Inventory Slots 5e Rule VariantDocument3 pagesInventory Slots 5e Rule VariantTelradaNo ratings yet

- NFM SKJHOLD Catalog 2019Document24 pagesNFM SKJHOLD Catalog 2019koswwwNo ratings yet

- MSNCTDocument9 pagesMSNCTPrincess DivaNo ratings yet

- 01 - Printable Bonus PackDocument101 pages01 - Printable Bonus PackVladimer SucmeovNo ratings yet

- E-2D Advanced HawkeyeDocument2 pagesE-2D Advanced Hawkeyecalifornium252No ratings yet

- Buddha's Teachings 45-1 PDFDocument23 pagesBuddha's Teachings 45-1 PDFPaingNo ratings yet

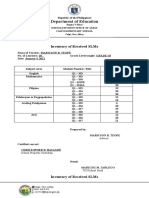

- Department of Education: Inventory of Received SlmsDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Inventory of Received SlmsMargel Airon TheoNo ratings yet

- 71559232Document11 pages71559232Nasr PooyaNo ratings yet