Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Environmental Politics: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription Information

Uploaded by

Ino SiozouOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Environmental Politics: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription Information

Uploaded by

Ino SiozouCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] On: 20 May 2011 Access details: Access Details:

[subscription number 907218003] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Environmental Politics

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713635072

Ecological modernisation, social movements and renewable energy

David Tokea a POLSIS, University of Birmingham, UK Online publication date: 18 January 2011

To cite this Article Toke, David(2011) 'Ecological modernisation, social movements and renewable energy', Environmental

Politics, 20: 1, 60 77

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2011.538166 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2011.538166

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Environmental Politics Vol. 20, No. 1, February 2011, 6077

Ecological modernisation, social movements and renewable energy

David Toke*

POLSIS, University of Birmingham, UK

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Ecological modernisation (EM) theory has involved a debate about the relative importance of concentrating on incorporating technological change into mainstream industry and, on the other hand, developing reexive capacities for debate involving social movements (SMs). However, such discussions may obscure the need to study the involvement of SMs in the development and deployment of ecological technologies themselves. This issue is investigated through an analysis of renewable energy, principally wind power. SM involvement in eco-technological development and implementation may be understated by EM theory. Keywords: renewable energy; wind power; social movements; ecological modernisation; eco-technology

Introduction My aim here is to understand how far ecological modernisation (EM) theory is correct in its conception of how social movements (SMs) are involved in eco-technical change, and how it may be necessary to place more attention on SMs in such developments. It is said that EM has become one of the two dominant paradigms in environmental policy (Wright and Kurian, 2010). Curran (2009, p. 203) says of EM: At its heart sits technological development. Yet if it is the case that EM is incorrect about the role of SMs in eco-technical change, it is important to examine the ways in which EM is lacking and to explain how the theory needs to be supplemented by more SM-oriented explanations. I do this mainly by reference to early (1970s to early 1990s) development of wind power and the commercial programmes that began the recent rapid expansion of this technology. I also briey discuss other renewable energy technologies where SMs may have been important to oer pointers for future research.

*Email: d.toke@bham.ac.uk

ISSN 0964-4016 print/ISSN 1743-8934 online 2011 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2011.538166 http://www.informaworld.com

Environmental Politics

61

All of this may have lessons for other eco-technologies, but renewable energy is crucially important in itself and occupies a pivotal role in the politics of environmental technology. This is because of the importance of energy issues to overarching environmental issues of our time, including fossil fuel resource depletion and global warming. Renewable energy is seen as a solution to such problems. The key research questions are: . What is the role that SMs have played in the development of renewable energy technologies and the nancial support systems such as feed-in taris? How have energy industry incumbents and top down R&D technology programmes been challenged by SMs? How do SMs learn about technological and policy development? In the light of answers to these questions, how should the role and scope of EM be re-evaluated with regard to development of eco-technologies?

.

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

. .

These questions are answered by a consideration of the theory of SMs and how this links with technologies, discussion of EM, the specic learning mode of SMs and how this leads to industrial development, the role of incumbents, and the political support for renewable energy policies, especially feed-in taris. The latter sections will be mostly concerned with empirical material, which will form the basis of the concluding analysis addressing the aforementioned research questions. Interviews were conducted with people who were active in the grassroots movement for renewable energy in Denmark, Germany and Spain, people selected because they were prime movers, or at least active participants, in the movement, and who could thus shed light on how the movement emerged and developed. Interviews were also conducted with technicians involved in largescale R&D programmes concerned with renewable energy to shed light on reasons why this type of initiative did not succeed. SMs and technologies Writers such as Melucci (1995, 1996), Oe (1985) and della Porta and Diani (1999) have argued that new forms of political activity associated with what are called new social movements have emerged in late modern conditions focusing on identity politics and cultural struggles as opposed to the more materially based and more institutionalised old SMs. It is also the case that old interest groups have appealed to cultural values and identity construction as much as new ones (Tilly 2004, pp. 7071). Nevertheless, theorists such as Tilly still use the term social movement because of its utility in encompassing a broad range of activities, types of organisation and orientations. This broad meaning of movements is used here. It may be the case that concern with technological issues is much more a hallmark of SM activity since World War II than before. To this extent, it may be a type of new SM activity.

62

D. Toke

However, there is doubt as to whether the SMs involvement with technology choices, as opposed to oppositional tactics, has received sucient attention from SM theorists. Jamison, in particular, maintains that SM theorists tend to focus on issues of identity or access to political resources rather than relations with technology. Meanwhile, science and technology studies (STS) tend to focus on the technology and treat the SMs as a marginal . . . amorphous background (Jamison 2006, p. 45). Jamison (2001, 2006) raised the issue of how SMs have, at certain times, adopted identities or cognitive praxis associated with technological innovation. Indeed, he argues that environmental movements that he studied (Eyerman and Jamison 1991, 1998) combined three dierent knowledge interests . . . cosmological, technological, and organisational (Jamison 2006, p. 47). These three concepts can be mobilised to help analyse SMs engaged in development of renewable energy. Rootes (2007) identies two ways of studying SMs: the cognitive approach just discussed and the other is by considering the SM as a network. Rootes (2007, p. 610) talks about the identication of an SM by scrutiny of the network links, collective action and evidence of shared identity. One way in which we can say that a technology SM is constituted is through information exchange. This can involve grassroots design and development of technologies, open discussion of technical issues and exchange of information on best design and best practice, and sometimes individual energy consumers involved as generators of renewable energy. This is distinct from conventional industrial practices where there is an emphasis on restricting information, in particular through the defence of patent rights. A second way of constitution is through the involvement of non-industrial groups such as municipalities and cause groups involved in campaigning for the establishment and maintenance of nancial support systems for renewables. The nancial support mechanisms, in particular feed-in taris, are aimed at enabling as wide as possible an array of actors in society to engage in commercial development of technologies rather than arrangements that favour major industrial incumbents. Hess (2007) argues that SMs have a generative as well as an oppositional approach to technology. In an era of globalization and market-oriented government policies, social movements have helped to politicize consumption and, in the process, to develop new markets and industries (Hess 2007, p. 85). He identies both industrial opposition movements (IOMs), such as antinuclear movements, and also technology product movements (TPMs), including organic agriculture, recycling and zero waste, green building, ethical investment and consumption, and renewable energy. The repertoires of the two types of movement have dierent emphases, with TPMs being more concerned with the creation of alternative institutions to diuse technologies than IOMs, whose typical repertoire places more emphases on street protests, for example. TPMs will also be more involved with reform scientists and technologists (Hess 2007, pp. 124125) and sometimes the alternative technologies and products are rst created by small-scale

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Environmental Politics

63

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

entrepreneurs who operate in a movement-like atmosphere (Hess 2007, p. 125). Hess develops the arguments about SMs further by investigating how they manifest themselves as a localist path to sustainability through local ownership, organisation and consumption of a range of goods and services (Hess 2009). Quantitative studies by Sine and Lee (2009) and Vasi (2009) show a correlation between the number of environmental groups and the installed capacity of wind power in various countries and the United States. In addition, Smith (2004) argues that bottom-up (or SM) processes are very important to understanding developments in sustainable technology, and van der Poel (2000) recognises the importance of SMs in driving many key technological changes. Ecological modernisation According to Janicke (2008, p. 558), ecological modernisation has been implicitly incorporated into concepts utilised by the EU, and such concepts all go far beyond the traditional end-of-pipe treatment and adopt a more comprehensive approach that focuses on environmental improvements through resource ecient innovation. EM theorists have certainly paid much attention to the development of technology as a way of ameliorating environmental problems (Mol 1995, 1996, Mol et al. 2000, Huber 2004, Janicke 2008, Janicke and Lindemann 2010). Mol (1995, p. 43) says that the general emphasis on the importance of the inuence of technology in socio-ecological transformations has remained a feature of the ecological modernization theory. Buttel describes this as an objectivist account in the sense that EM is used to analyse how ecological change occurs. This objectivist account is typied in particular by Mols approach to the role of conventional industrial incumbents and environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the Dutch chemical industry. Although environmental NGOs played a key role in setting objectives for pollution reduction, it was conventional industry that chose and implemented the technological means to achieve the environmental objectives. Mol (1995, p. 371) comments: Environmental organizations remain essential in raising public pressure and political support for environmental reform, whilst their positions in environmental disputes and their strategies towards state and economic producers are slowly transforming. Yet NGOs have developed in a reformist direction: A radical goodbye to these institutions (of modernity) is no longer considered necessary nor desirable from an environmental perspective . . . (environmental NGOs) can increasingly be interpreted as an one-issue movement. Its prime focus is environmental quality, and automatic solidarity and common agenda (Mol 2000, pp. 4849). Mol points to a heightened desire by environmental NGOs to talk to and to sometimes form alliances with conventional industry to support eorts to reduce pollution.

64

D. Toke

In addition, key mainstream EM texts appear to downgrade the signicance of the involvement of SMs in developing the technologies themselves. The mainstream or objectivist EM account implies that the environmental movement has a limited role to play in ecological transformation in comparison to big capitalism and conventional economic actors (Murphy 2000, p. 2, Spaargaren 2000, pp. 5152). Spaargaren, referring to the decentralised grassroots soft paths approach to energy technologies advocated by writers such as Lovins (1977), comments that:

When soft-path technologies are propagated outside the market their chances of survival seem to be less in comparison to the situations in which they are incorporated in the strategies of major industrial actors. (Spaargaren 2000, p. 52)

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

It may be right to argue that the role of SMs in developing EM technologies may have declined (Huber 1991 cited Mol 1995, p. 36). However, this does not remove a need to study SM activity, involving direct participation in technological development and deployment, if we are to properly understand the role of EM in the case of renewable energy. As will be argued later, it may simply be wrong to marginalise the importance of SM activity both in developing renewable energy and mobilising political support for incentives for renewable energy. This activity has often been against the wishes of the major industrial (energy) actors themselves. Moreover, when an EM analyst speaks of technologies being adopted by major industrial actors, is s/he talking about the existing, conventional actors, or a new industry that attempts to replace the conventional one? This new industry may be supported by a coalition including SM actors and engaged in a political battle with the conventional industry. As will be discussed, there is evidence of the latter in some of the cases. Buttel (2000) also describes what he calls a social constructionist approach to EM, which sees EM as discourses about environmental policy that may or may not result in sustainable ecological reform. This is represented by Hajer who criticises the so-called techno-corporatist mainstream EM theory, which ordains the creation of new expert organizations where the best people can work in relative quiet (Hajer 1995, p. 281). Hajer commends the greater involvement of environmental NGOs in EM, but his central focus is on searching for new institutional arrangements for inter-discursive forms of debate (Hajer 1995, pp. 281282). He spends little time analysing the involvement of SMs in technological change and innovation. Objectivist (mainstream) and social constructionist EM approaches may dier on the degree of importance and political role of SMs in EM. Nevertheless, they share a common prime focus of seeing the role of SMs as being in the politics of environmental problems rather than intervening in development and deployment of specic technological solutions to the problems. We can see from this that there may be a decit in both these approaches to EM theory in considering the role of SMs in technological innovation and deployment. Certainly, it is dicult to nd EM analyses that

Environmental Politics

65

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

spend the bulk of their time discussing the relationships of SMs to technology per se. The debate among the dierent varieties of EM (Hajer 1995, Mol 1996) seems to imply that there is some sort of opposition between market-based technological paths and elite decisions about regulation on the one hand, and with social reexivity (Mol 1996, pp. 316319) on the other. Yet technological activity is not necessarily the opposite of SM activity. There are key periods when SMs and technological development and deployment may be combined, not merely in policy debates (reexive or elite) but in terms of SM participation in the technological development and deployment itself. Indeed it may be that, far from SM activity in technological implementation representing a backwater or deception, it is a signicant, perhaps essential, driver of ecological reform. SM learning and wind power development This section begins, and concentrates mainly, on Denmark, where the modern wind revolution mainly began. A brief discussion of early developments in Germany, Spain and California follows since they have been early leaders in wind power development. The Danish commitment to generating electricity from wind has been very strong since the nineteenth century. This technological tradition has been associated with a social tradition of coping with a lack of domestic energy sources and a rural tradition of common action to solve problems. Folk High Schools taught cooperative patterns of learning in Denmark. This was established in the wake of the defeats in the war with the German Confederation in 1864 and spread through teachings by the priest Grundtvig. This grassroots bottom up learning was inuential in the early development of wind and biogas technology in the 1970s and 1980s. (For accounts of the Danish development of modern wind power technology, see Karnoe 1990, Heymann 1998, Olesen 1998, van Est 1999, Asmus 2001, Garud and Karnoe 2001, 2003, Nielsen 2001, Kemp et al. 2001.) After the start of the energy crisis in 1973, the rural cooperative tradition was mixed with a heightened sense of common purpose, driven by the energy crisis and the desire to nd alternatives to nuclear power. In terms of Jamisons cosmological, technological and organisational aspects of the SM, opposition to large-scale environmentally destructive activity (including nuclear power) provided the cosmology for the movement, knowledge about renewable energy became the technological focus, and the grassroots information-sharing Folk High School tradition became the organisational basis for the SM. As Preben Maegaard, who was the President of the Organisation for Renewable Energy (OVE) from 1979 to 1984, put it:

You could not nd another country that was so dependent on oil and therefore the reaction was very strong in the general public and the establishment, its response to it, that was to say now we have to turn to atomic energy . . . but

66

D. Toke

there was a reaction in the population saying that that would create a new dependency. And there came some movements against that. And the question was how to get involved in that and that was by saying we have natural resources we can use the sun, the wind and the biomass. And we soon found out that the know how available was very limited but we formed a local initiative group that gathered regularly and also gathered as much information as was available. (Interview with Preben Maegaard, 18 April 2009)

The Organisation for Renewable Energy organised regular regional meetings, or traef, to share practical know-how on how to develop the dierent renewable energy technologies, particularly wind. The meetings involved farmers who bought wind turbines (and sometimes made them) to serve their own energy needs and dierent types of local craftsmen, especially blacksmiths. In Denmark, as in various other parts of the world, there was a tradition since the end of the nineteenth century of often locally manufactured small o-grid, and sometimes grid-connected, wind turbines, not to mention R&D eorts in places like Germany to develop grid-connected wind turbines (Heymann 1998, pp. 653654, van Est 1999, p. 208). After the 1973 oil crisis, in Denmark, grassroots activists used a design of a demonstration wind generator by Johannes Juul (installed in 1957) as a start. An interactive process involving feedback amongst the electricity user/ generators and early small (often backyard) manufacturers laid the basis for a more conventional industry to be developed in the 1980s. The most popularised early grid-connected machine was made by a farmer, Christian Riisager. A journalist, Torgny Mller (now one of the three proprietors of Wind Power Monthly, the global industry trade magazine), reported the output, giving the technology more credibility. However, there were a large number of people involved in developing prototype machines (in rural backyards and workshops) from 1975 onwards. In fact, all but 1 of the 20 manufacturers in 1978 had ceased to exist by 1982, to be replaced by 20 new manufacturers, just as the industry was showing the rst signs of standardisation and domination by conventional companies such as Vestas. Even then, there was continuing interchange of information about technical best practice. No patents were taken out on the technology until the 1990s. Indeed, in the tradition of Danish rural cooperation for the common good, patents for rural technology were specically banned by a Danish law of 1885 (interview with Preben Maegaard, 18 April 2009). Hence, an idealistic belief in a new alternative technology set up the conditions for a niche to develop in ways in which conventional industry, with its patent-based secrecy and expectation of early commercial returns, would nd very dicult to replicate. The industry advanced through incremental upscaling of size from the earliest 20 kW grid-connected machines (Gipe 1995, pp. 6895). In Maegaards view, the centrally funded R&D projects were a waste of money, the funds being awarded to qualied people to gain patents. The grassroots activists could not access such funds, and the useful projects were funded from below.

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Environmental Politics

67

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

In fact the only successful large-scale wind turbine (in terms of working for several years) was built by a left wing Folk High School at Tvind. It was a groundbreaking 2-MW machine whose construction began in 1975 and which started working in 1978. It was a very inuential design because of the specially devised control system and breglass blades. These innovations were developed as a result of open cooperation between activists based at the Folk High School, academics from the Technical University of Stuttgart and Denmark Technical University, several private engineering manufacturers and the Danish Governments Risoe Atomic Energy research laboratory. These cooperations were all un-remunerated, and the technicians from Risoe worked unocially in their spare time (interview with Joep Nagel, one of the organisers of the Tvind High School in the 1970s concerned with building the windmill, 7 May 2009; P. Maegaard The Tvind windmill showed the way, article available from the author, 2009). This pattern of cooperation is described as openness, cooperation, no patents, no barriers, all working together. And out of this grows an industry because there is someone who wants to buy (interview with Preben Maegaard, 18 April 2009). At rst, it was individual farmers who provided the market for wind turbines, but from 1979 to 1983 slightly larger machines were sold to locally based wind power cooperatives or wind power schemes owned by local communities. As we shall discuss in greater detail later, the renewable energy movement pressed the utilities to pay operators of wind turbines premium rates for the electricity so generated and secured support from the Danish Parliament when the utilities refused to make good payments. Such payments evolved into a system now used to support renewable energy: feed-in taris.1 At this point, something needs to be said about the link between the early period of SM learning and the development of a more conventional-looking, if still emergent, wind turbine industry in the early 1980s. Linking the SM to an industry As Kemp et al. (2001, p. 286) put it: The rst turbines were purchased by idealistic buyers whose early purchases helped to build expertise. After 1977, a wind turbine industry emerged, consisting of companies that used industrial manufacturing techniques and standardised industry produced parts. Companies such as Vestas, Nordtank and Bonus had been small companies manufacturing agricultural equipment. To them, wind turbines were a new, potentially interesting market, initially for wind power cooperatives that began to emerge in the Danish countryside. They utilised the ideas of the grassroots engineers to develop their machines (Heymann 1998, p. 662), and grassroots carpenters, mechanics and blacksmiths such as Riisager and Jorgensen. Vestas took up use of Jorgensens design in 1979 and developed their products using trial and error learning. Firms also learnt from each other at Windmeetings (Garud and Karnoe 2003, p. 282). In 1978, the Danish Wind Turbine Test Station (DWTS) was set up to test wind turbines for reliability. The main mover was Helge Petersen, who had

68

D. Toke

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

participated in the Tvind school wind turbine project (Garud and Karnoe 2001, p. 14). The Danish parliament soon passed a law requiring that wind turbines be tested at the DWTS. Initially, the nascent Danish wind industry relied on individual farmers and cooperatives to provide a wind turbine market. However, the Californian programme was crucial in allowing the nascent Danish wind industry to consolidate its foothold. From 1983, the Californian wind market took o in the wake of incentives put in place largely at the behest of Governor Jerry Brown in response to the demands of soft energy paths campaigners and environmental NGOs (Roe 1984, Righter 1996, van Est 1999). The wind farms in California were constructed by developers independent of the incumbent utilities, and the programme was developed after overcoming strong opposition from the utilities. Spain and Germany were also early leaders in the development of wind power. In SM terms, there were parallels with Denmark in that there were strong anti-nuclear movements in both countries in the 1970s and in 1980s (Rudig 1990). In Spain, a workers cooperative, Ecotecnia, formed at the beginning of the 1980s, designed and made wind turbines in the 1020 kW range. Based on the Danish experience, the cooperative was started by a group of nine persons with high technical qualications, committed to environmental thought and the practice of alternative technology (Puig 2009, p. 191). Among the inuences on them were work by Lovins (1977) and the SM, which developed through projects such as the Tvind windmill (Puig 2009, pp. 191192). According to Josep Puig (interview, 13 October 2009):

a group of these people (the founders of Ecotecnia) were involved in the antinuclear movement and many times when they were speaking against nuclear a lot of people asked If we dont build nukes what to do? . . . and at the time, some people knew that in Denmark they were starting with wind and they were developing quite well, so we decided to propose to build a wind machine of 15 kW with the government.

Puig, who was a founder-member of Ecotecnia said that by the end of the 1980s Ecotecnia only sold 20 to 30 small machines, 15 to 30 KW to the dierent administrations in dierent regions of Spain because they wanted to make some demonstration programmes . . . IDAE started developing renewable energy programs . . . at that time it was a woman quite sensitive to renewables and anti-nuclear in the ministry and also because the rst director of IDAE was a man quite interested in renewables (interview, 13 October 2009). IDAE is the Spanish Renewable Energy Agency, which was established in 1984. Spain was especially sympathetic to renewable development, not merely because of post-Franco anti-nuclear sentiment, but also because Spain, like Denmark, was heavily dependent on energy imports. In Germany, there was farmer interest in setting up wind turbines in the 1980s, but, as in the case of Spain, wind turbines were developed from Danish

Environmental Politics

69

models. Although Germany had some tradition of early design of wind turbines, for instance through Hutter in the 1940s and 1950s, very little eective innovation seems to have occurred in the 1970s and early 1980s prior to the emergence of a more conventional wind energy industry. The rst (and still) successful German wind turbine manufacturer, Enercon, did not begin production until 1985.

A comparison test of eight German 10-kilowatt turbines of dierent designs and one Danish turbine on the small German North Sea island of Pellworm in the early 1980s clearly showed the shortcomings of German turbine development. Five German turbines failed before the test even started; the remaining three failed after a few months. Only the Danish Windmatic turbine (which was not among the most successful models used in California) operated reliably. (Heymann 1998, p. 664)

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Later I will discuss the SM activity concerned with supporting incentives to deploy renewable energy. The need to do this largely stems from the reluctance, delay and often downright opposition of major energy utilities to the nascent wind power industry. The role of incumbents and centralised R&D According to mainstream EM theory, it could be expected that the big electricity industry players would be the agents who would accomplish environmentalist demands for the development of renewable energy technologies. Wind power R&D programmes did occur, but with little success. David Lindley was an academic interested in wind power who came to work in the United Kingdom for Taylor Woodrow, a big civil engineering rm, in 1978, and became involved in R&D programmes for wind power. In what proved to be a typical example in industrialised countries, he talks about the pressures that led to R&D projects being concerned with developing large machines.

[The UK Government] started o by saying Lets look at what was the biggest turbine we could build. Now it was partially, I think, because . . . the government was interested in looking at renewables in a modest way, and when that was tested against the wishes of the monopoly, the CEGB (the then-nationalised Central Electricity Generating Board) itself were not very favourably disposed towards wind. One of the arguments they were using at the time was rather a nonsense because you didnt want to replace a 1000 megawatt power station with 10,000 little windmills scattered over London, well a big windmill was 100 kilowatts in 1978. (Interview with David Lindley, 19 March 2009)

The government preferred to build a 3-MW design, which was constructed in the Orkney Islands but worked for only some short periods. In this respect, it was like the other products of the large-scale R&D projects organised in other industrialised countries. In the United States, NASA and the Department of Energy persuaded Congress to fund a series of increasingly large wind turbines in the Mod series

70

D. Toke

from 1978 to 1989, but all suered from repeated performance failures. Designers appeared slow to learn from mistakes, and the components and associated manufacturing toolkits were expensive (Gipe 1995, pp. 103 107). The ground-breaking Gedser turbine (the brainchild of Johannes Juul), which formed the basis of many grassroots designs for wind turbines (as earlier mentioned), had been nanced by a Danish electricity utility that discontinued the experiment in 1967 on the basis that it was uneconomic (Heymann 1999, pp. 117118). In 1977, the Danish Government gave responsibility for developing the wind power programme to a committee run by the electricity utilities. It may seem surprising (especially in view of the grassroots-induced Danish wind development) that the rst move by the utilities, in 1977, was to approach the US Government to purchase wind turbine blade technology. This did not succeed. They opted for development of large machines, of the 630750 kW range, and then a 2-MW project, Nibe B (van Est 1999, pp. 8486). This programme took a long time to organise and made no signicant contribution to the wind turbine programme in Denmark. Indeed, the Danish electricity utilities were hostile to the idea of the privately owned wind turbines that were springing up, declaring that wind turbines should be owned by the utilities and that they should be commercially viable using market prices for the value of electricity (van Est 1999, p. 86). In Germany, the opposition of the utilities to wind power was often intense. Despite local enthusiasm for windmills, the utilities were slow to connect them and refused to pay more than minimal rates for the power sent into the distribution system (Heymann 1999, pp. 120122). When, in the mid-late 1970s, the German federal government attempted to organise a R&D programme, the utilities initially refused to cooperate at all. Eventually, when one utility agreed to take part, the same pattern of designing a large turbine (as in other industrialised countries) followed. The result was the Growian 3-MW machine, which stood still for most of the time (Heymann 1999, p. 124). In Spain, the approach was signicantly dierent. The pioneers were Ecotecnia, a company formed by anti-nuclear activists who began discussing alternative energy paths in the late 1970s. The Spanish Government organised an open bidding competition for R&D funds, some of which was won by Ecotecnia, which led the way in demonstration wind turbines in the 1980s. However, at the end of this decade, some Spanish utilities began to take a serious interest in wind power. Iberdrola, in particular, worked in collaboration with Spanish central and regional governments and established Gamesa Eolica, a turbine manufacturer. Initially this used Danish designs, and indeed until 2001 the Danish turbine manufacturer Vestas was the majority shareholder in Gamesa (Dinica 2003, pp. 183314, Stenzel and Frenzel 2008, Puig 2009). One possible explanation for the relatively greater enthusiasm of Spanish government and utilities for wind power is that not only was Spain very dependent on energy imports (like Denmark and to a lesser extent like Germany), but post-Franco it was rapidly developing economically with very

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Environmental Politics

71

rapidly rising demand for electricity and a consequent thirst for new energy sources. Feed-in taris As discussed earlier, an important area of SM activity has been to support the concept of feed-in taris. This institution involves obliging the utilities to accept all domestically generated renewable electricity oered to the grid and to compensate the generators at specied levels. Feed-in tari rates are oriented on the principle of fair return (that is a cost-covering tari) for a given technology. [For a recent analysis of the importance of this, see Verbruggen and Lauber 2009, p. 5736.] The feed-in tari is a means of aording independent generators (as opposed to the main electricity generator/ suppliers incumbents) stable income levels that oer investors and banks condence in the nancial returns from renewable energy projects. Feed-in taris have emerged as the most important means of supporting renewable energy programmes in Europe. Three countries with feed-in taris Germany, Denmark and Spain blazed the trail in the early development of wind power. Denmark remained in the lead in installed capacity well into the 1990s, but by the end of 2003, Germany led, and 63% of global wind power capacity was installed in these three countries (Wind Power Monthly 2004). In Denmark, the farmers and cooperatives who put up the early wind schemes undertook a long battle with the utilities over the obligation to accept all wind power delivered to the grid and to pay reasonable rates for it. Initially, the best the independent generators could negotiate was a system of payment parity with the per kW h prices paid to owners of large power stations. In 1980, a state system of subsidies was introduced to cover 30% of capital costs, a proportion that varied between then and the end of the subsidy programme in 1989 (Nielsen 2001, p. 218). Eventually in 1984, a system of premium prices for wind power was agreed, paid as a high proportion of retail prices for electricity produced by cooperative and privately owned turbines. The prices paid by utilities for wind power were gradually increased after lobbying by the grassroots Organisation for Renewable Energy (OVE) and organisations representing cooperative and private wind turbine owners (Nielsen 2001, pp. 275278). German interest in wind power dramatically increased as the 1980s moved on, driven especially by activists in the anti-nuclear movement. One such activist was Sven Teske, who later became a Greenpeace Energy Campaigner. He said:

[T]here was a need for the anti nuclear movement to develop solutions . . . [T]hey copied the rst wind turbine machines from Denmark in the 80s . . . It was a grassroots technology in the 80s and the beginning of the 90s. This grassroots movement was asking for feed-in taris . . . asking for the right to connect these machines to the grid and the big utilities refused to do it . . . (until) after almost 10 years of lobbying . . . it was mainly farmers and environmentalists in the north of

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

72

D. Toke

Germany and they just connected their turbines illegally to the grid. They just fed it in. (Interview with Sven Teske, Energy Campaigner for Greenpeace Germany, 14 September 2004)

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Eventually, grassroots pressure from independent renewable generators (wind but also small hydro) succeeded in persuading sucient backbench members of the Bundestag to support legislation to enact a feed-in law to take eect in 1991. This gave premium guaranteed payments to renewable energy generators for 20 years. The utilities persuaded the Ministry for Economic Aairs to oppose the legislation, but this opposition was overcome (Jacobsson and Lauber 2005, pp. 135136). A movement defended the feed-in tari law against attack by the utilities in 1997. A range of groups including trade unionists involved in the renewables industry, farmers, environmental groups and renewable trade associations organised a large demonstration against proposals to cut the levels of the feedin tari (Jacobsson and Lauber 2005, p. 136). Despite parliamentary and legal challenges orchestrated by the utilities, the legislation was renewed in 1998. The legislation was widened in 2000 to give higher payments to a number of dierent renewable fuels, including various forms of biomass and solar photovoltaics (PV). In Spain, feed-in taris developed dierently as part of a renewables programme backed by a national energy consensus (including major utilities). Initially, condence in the developing Spanish renewables industry was created through publicprivate partnerships, with the private sector gaining condence in the security of their investments through part-state investments (Dinica 2008). As mentioned earlier, IDAE was a key mover in this state-backed renewables programme. A feed-in tari system developed from 1991, although initially there were no long-term guarantees for the levels of the tari. It was only in 2004 that the present system of 20 years guarantees of feed-in taris for particular projects was introduced. Other potential renewable case studies? There is some prima facie evidence that there is considerable SM inuence in the early development of renewable energy technologies other than wind power. There is insucient space here to study all the technologies and their stages of development, but it is useful to give some pointers for future research in this area. Biogas is now becoming a major renewable energy technology. Over 1400 MW of biogas-red small (farm-based) generating plant (the equivalent of a large nuclear power station) is now in operation in Germany (DENA 2008), and biogas programmes in other countries are expanding. This technology involves anaerobic digestion and began with farmers using farm wastes as fuel. Again, like early wind power, it began as energy users also acted as energy generators. Moreover, the technology was developed through the same cooperative information-sharing process associated with

Environmental Politics

73

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

wind power (Raven and Gregerson 2007, interview with Preben Maegaard, 18 April 2009). Various groups and individuals were active in encouraging farmers to adopt the technology around Germany for idealistic motives without any expectation of nancial gain. Arthur Wellinger, now the president of the European Biogas Association, in the 1970s1990s, was an academic and campaigner for biogas technology. We organised the Biogas tours, by bus we went to the plants. We started o with one busload full of farmers and then we did 8 tours a year, sometimes with 2 to 3 buses, so I think it was a really big deal. I think that gave the breakthrough, these bus tours to biogas installations (interview with Arthur Wellinger, 6 January 2010). Another possible research area for SM activity in renewable energy is the case of solar PV. Germany has accounted for a large proportion of the early growth of grid-connected solar PV. As in Denmark in the 1970s and 1980s, this was done in the context of strong anti-nuclear movements (Jacobsson et al. 2004, p. 16). The campaign for a specic, cost covering or fair return-based, solar PV feed-in tari was organised through a broad-based movement, again, usually in opposition to the utilities. Cities led by Hammelburg, Freising and Aachen set feed-in taris for solar PV in 1993. This pressured the federal parliament to introduce a special premium-rate nationwide solar PV feed-in tari in 2000 (Jacobsson et al. 2004, pp. 1519, Jacobsson and Lauber 2005, Fell 2009, p. 5). Conclusion SMs have played a crucial role in the early development of renewable energy technologies such as wind power because, apart from anything else, the dominant energy incumbents, the utilities, were initially unwilling or unable to develop the technologies. A strong industrial opposition movement (IOM) (Hess 2007) existed in the form of the anti-nuclear movement whose demands for a technological substitute for nuclear power could not initially be fully resolved under the existing energy-industrial regime. Of course, as time goes on, conventional incumbents are increasingly involved in the deployment of renewable energy. Nevertheless, in the 1970s and 1980s (and for sometime thereafter), the incumbents either saw their interests as being directly threatened or, at least initially, lacked the innovative capacity and will to develop renewable energy technologies. For this reason, if for no other, the standard operating plan of EM (Mol 1995) whereby the main industry reforms its practices to conform to environmentalist pressures could not work. National conditions and traditions inuenced the balance between SM activity and incumbent opposition. Spain saw the most enthusiastic involvement from incumbents in renewable energy, but even there the technology was borrowed initially from the Danes (where the wind power technology SM had been in action) and only brought onto the energy agenda by a grassroots movements that brought into being the pioneering Ecotecnia turbine makers.

74

D. Toke

Indeed, there is evidence of continued reluctance by industrial incumbents to develop renewables, at least beyond a certain point. In the United Kingdom, companies like EDF have called for limits on renewable energy deployment to leave room for nuclear power generation (EDF 2009). In Germany, leading utilities continued to oppose the feed-in tari laws after 2000. During the debates that led to the 2009 EU Renewable Directive, Eurelectric, the organisation representing big electricity utilities, argued for a system of panEU tradeable certicates, which was seen by the main renewable energy trade associations as a barrier to smooth deployment of renewables (Toke 2008). Since the purpose of technology SMs is to maximise the use of knowledge to develop a technology, they will involve as many agents as possible and engage in activities that maximise the ease of transfer of knowledge. Hence, there is a great emphasis on open meetings, idealistic sharing of knowledge through free publication and campaigns to publicise the technologies. This is opposite to conventional industrial practice where companies attempt to keep information about technological innovation to themselves in order that they rather than their competitors may reap the returns on investment in that technology. SMs are crucial to the development of renewable technologies in the eld of politics as well as technology. Feed-in taris are benecial for independent generators who need guaranteed access to the grid and long-term security of income streams that feed-in taris can provide to allow prospective generators to borrow money from banks and persuade investors to support the projects. Energy incumbents can use their own resources, income streams and bond issues to nance new plant. It may be possible for independents to secure power purchase agreements from the energy incumbents, but, as was clear in the early days of renewable energy, the utilities are loath to oer agreements and will not oer premium prices to renewable generators in the absence of some incentive scheme organised by government. Since the aim of a technology SM is to encourage as wide as possible a range of agents to adopt the technology, it is no surprise that feed-in taris became the favoured nancial support technique for the movements supporting renewable energy. Hence, as implied earlier, one hypothesis that ows from this case study is that EM theorys account of the role of SMs (and therefore EMs own applicability) becomes less relevant when there exists a TPM. In the energy sector, conventional energy industries, with their own path-dependent reliance on fossil fuels and nuclear power, may be reluctant to promote renewable energy technologies. In many countries, even today, energy utilities are only developing renewable energy because of incentive programmes that have been politically driven by a coalition of social and commercial forces supporting renewable energy. However, a further hypothesis is that as the mainstream energy industries derive an increasing proportion of their income from renewable energy, SM involvement and political engagement in the details of renewable energy policy will decline. This would allow a more conventional EM explanation, albeit with a bigger emphasis on the need to explain the

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Environmental Politics

75

importance of SM activity as a precursor to large-scale implementation. However, even in this instance, in at least some national cases, questions over the conventional EM explanation would remain because of the continued involvement of SMs to support feed-in taris to ensure the ourishing of a renewables industry that is independent of the incumbents. It is likely that cases involving other technologies may also be analysed more protably from a SM point of attack rather than (solely) from that of EM. Acknowledgements The author acknowledges the help of the four anonymous peer reviewers of this article. Note

1. It should be noted that while Denmarks wind programme built up to providing around 20% of Danish electricity by 2003, the coming to power of right wing coalition governments since the end of 2001 led to the end of the onshore wind power programme (Ryland 2010).

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

References

Asmus, P., 2001. Reaping the wind. Washington, DC: Island Press. Buttel, F., 2000. Ecological modernization as social theory. Geoforum, 31, 5765. Curran, G., 2009. Ecological modernisation and climate change in Australia. Environmental Politics, 18 (2), 201217. della Porta, D. and Diani, M., 1997. Social movements: an introduction. London: Blackwell. DENA (German Energy Agency), 2008. The German biogas industry [online]. Available from: http://www.renewables-made-in-germany.com/en/biogas/ [Accessed June 2009]. Dinica, V., 2003. Sustained diusion of renewable energy. Twente: Twente University Press. Dinica, V., 2008. Initiating a sustained diusion of wind power: the role of public private partnerships in Spain. Energy Policy, 36 (9), 35623571. EDF, 2009. UK renewable energy strategy consultation response by EDF, full responses to the UK renewable energy strategy consultation, oine responses, organisations E to G [online]. Available from: https://bham.blackboard.com/webct/urw/lc15872144400 61.tp0/cobaltMainFrame.dowebct [Accessed 18 November 2010]. Eyerman, R. and Jamison, A., 1991. Social movements. A cognitive approach. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press. Eyerman, R. and Jamison, A., 1998. Music and social movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Fell, H., 2009. Feed-in tari for renewable energies: an eective stimulus package without new public borrowing. Berlin: Oce of Hans-Josef Fell, Member of the German Bundestag. Garud, R. and Karnoe, P., 2001. Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship: bricolage versus breakthrough [mimeograph]. New York: University of New York. Garud, R. and Karnoe, P., 2003. Bricolage versus breakthrough: distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32, 277 300.

76

D. Toke

Gipe, P., 1995. Wind energy comes of age. New York: John Wiley. Hajer, M., 1995. The politics of environmental discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hess, D., 2007. Alternative pathways in science and industry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Hess, D., 2009. Localist movements in a global economy sustainability, justice, and urban development in the United States. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Heymann, M., 1998. Signs of hubris: the shaping of wind technology styles in Germany, Denmark, and the United States, 19401990. Technology and Culture, 38 (4), 641 670. Heymann, M., 1999. A ght of systems? Wind power and electric power systems in Denmark, Germany, and the USA. Centaurus, 41, 112136. Huber, J., 1991. Ecologische modernisering; weg van schaartse, soberheid en bureaucratie? In: A. Mol, G. Spaargaren, and A. Klapwijk, eds. Technologie en milieubeheer. Tussen sanering en ecologische moderisering. Den Haag: SDU. Huber, J., 2004. New technologies and environmental innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Jacobsson, S. and Lauber, V., 2005. Germany: from a modest feed-in law to a framework for transition. In: V. Lauber, ed. Switching to renewable power. London: Earthscan, 122158. Jacobsson, S., Sanden, B., and Bangens, L., 2004. Transforming the energy system the evolution of the German technological system for solar cells. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 16 (1), 330. Jamison, A., 2001. The making of green knowledge. Environmental politics and cultural transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jamison, A., 2006. Social movements and science: cultural appropriations of cognitive praxis. Science as Culture, 15 (1), 4559. Janicke, M., 2008. Ecological modernisation: new perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16, 557565. Janicke, M. and Lindemann, S., 2010. Governing environmental innovations. Environmental Politics, 19 (1), 127141. Karnoe, P., 1990. Technological Innovation and industrial organisation in the Danish wind industry. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 2, 105123. Kemp, R., Rip, A., and Schot, J., 2001. Constructing transition paths through the management of niches. In: R. Garud and P. Karnoe, eds. Path dependence and creation. London: Routledge, 269299. Lovins, A., 1977. Soft energy paths: toward a durable peace. London: Penguin. Melucci, A., 1995. The process of collective identity. In: H. Johnston and B. Klandermans, eds. Social movements and culture. London: University College London. Melucci, A., 1996. Challenging codes: collective action in the information age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mol, A., 1995. Ecological modernisation theory and the chemical industry. Utrecht: Van Arkel. Mol, A., 1996. Ecological modernisation and institutional reexivity: environmental reform in the late modern age. Environmental Politics, 5 (2), 302323. Mol, A., 2000. The environmental movement in an era of ecological modernisation. Geoforum, 31, 4556. Mol, A., Spaargaren, G., and Buttel, F., 2000. Environment and modernity. London: Sage. Murphy, J., 2000. Ecological modernisation [Editorial]. Geoforum, 31, 18. Nielsen, K., 2001. Tilting at windmills: on actor-worlds, socio-logics and techno-economic networks of wind power in Denmark 19741999. Thesis (PhD). University of Aarhus.

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

Environmental Politics

77

Oe, C., 1985. New social movements: changing boundaries of the political. Social Research, 52, 817868. Olesen, G., 1998. Large scale implementation of renewable and sustainable energy. Hjortshoj: OVE/INFORSE-Europe. Puig, J., 2009. Renewable regions: life after fossil fuels in Spain. In: P. Droege, ed. 100% Renewable energy autonomy in action. London: Earthscan, 187204. Raven, R. and Gregerson, K., 2007. Biogas plants in Denmark: successes and setbacks. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 11 (1), 116132. Righter, R., 1996. Wind energy in America a history. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. Roe, D., 1984. Virgins and dynamos. New York: Random House. Rootes, C., 2007. Environmental movements. In: D. Snow, S. Soule, and H. Kriesi, eds. The Blackwell companion to social movements. Oxford: Blackwell, 608640. Rudig, W., 1990. Anti-nuclear movements: a world survey of opposition to nuclear energy. Harlow: Longman. Ryland, E., 2010. Danish wind power policy: domestic and international forces. Environmental Politics, 19 (1), 8085. Sine, W. and Lee, B., 2009. Tilting at windmills? The environmental movement and the emergence of the U.S. wind energy sector. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54, 123155. Smith, A., 2004. Alternative technology niches and sustainable development. Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice, 6, 220235. Smith, A., 2005. The alternative technology movement: an analysis of its framing and negotiation of technology development. Human Ecology Review, 12 (2), 106119. Spaargaren, G., 2000. Ecological modernisation theory and changing discourses on environment and modernity. In: G. Spaargaren, A. Mol, and F. Buttel, eds. Environment and modernity. London: Sage, 4172. Stenzel, T. and Frenzel, A., 2008. Regulating technological change the strategic reactions of utility companies towards subsidy policies in the German, Spanish and UK electricity markets. Energy Policy 36 (7), 26452657. Tilly, C., 2004. Social movements, 17682004. Boulder, CO: Paradigm. Toke, D., 2008. The EU Renewables Directive what is the fuss about trading? Energy Policy, 36, 29912998. van der Poel, I., 2000. On the role of outsiders in technical development. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 12 (1), 383397. van Est, R., 1999. Winds of change a comparative study of the politics of wind energy innovation in California and Denmark. Utrecht: International Books. Vasi, I., 2009. Social movements and industry development: the environmental movements impact on the wind energy industry. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 14 (3), 315336. Verbruggen, A. and Lauber, V., 2009. Basic concepts for designing renewable electricity support aiming at a full-scale transition by 2050. Energy Policy, 37 (12), 57325743. Wind Power Monthly, 2004. The windicator: operating wind power capacity. Wind Power Monthly, January, 20 (1), p. 66. Wright, J. and Kurian, P., 2010. Ecological modernization versus sustainable development: the case of genetic modication regulation in New Zealand. Sustainable Development [online]. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/ 122612504/abstract [Accessed February 2010].

Downloaded By: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] At: 12:13 20 May 2011

You might also like

- Harvesting Rainwater: Catch Water Where it FallsDocument18 pagesHarvesting Rainwater: Catch Water Where it FallsBhavesh TandelNo ratings yet

- 3.1.4 - Environmental MovementsDocument10 pages3.1.4 - Environmental MovementsMatthew PringleNo ratings yet

- Falcon's Stop Work PolicyDocument9 pagesFalcon's Stop Work Policyramkumardotg_5807772No ratings yet

- Civil Service Exam Coverage 2016Document17 pagesCivil Service Exam Coverage 2016MikoyIgop100% (2)

- Organizational Behavior & Communication - StarbucksDocument5 pagesOrganizational Behavior & Communication - StarbuckshuskergirlNo ratings yet

- ECOLOGY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATIONDocument60 pagesECOLOGY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATIONRhea Lyn Monilla68% (19)

- Technology Innovation For Sustainable DevelopmentDocument42 pagesTechnology Innovation For Sustainable Developmentcyrille jane mayorgaNo ratings yet

- 5874 - W1 Robbins - Chapter1 - Managers and You in The WorkplaceDocument43 pages5874 - W1 Robbins - Chapter1 - Managers and You in The WorkplaceIkrima Nazila FebriantyNo ratings yet

- Energy, Resources and Welfare: Exploration of Social Frameworks for Sustainable DevelopmentFrom EverandEnergy, Resources and Welfare: Exploration of Social Frameworks for Sustainable DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- City of MarikinaDocument18 pagesCity of MarikinaJana ElediaNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Creative IndustriesDocument12 pagesInnovation in Creative Industries陈松琴No ratings yet

- The Social Shaping of Technology. Williams EdgeDocument35 pagesThe Social Shaping of Technology. Williams EdgesakupljacbiljaNo ratings yet

- Geels 2011 EIST Response To Seven CriticismsDocument17 pagesGeels 2011 EIST Response To Seven CriticismsAntonio MuñozNo ratings yet

- 1985 Soc Inn and It NordicDocument33 pages1985 Soc Inn and It NordicIan MilesNo ratings yet

- The Social Shaping of TechnologyDocument50 pagesThe Social Shaping of TechnologyalinakekobNo ratings yet

- A Feminist Approach To Climate Change Governance: Everyday and Intimate PoliticsDocument12 pagesA Feminist Approach To Climate Change Governance: Everyday and Intimate PoliticsgopiforchatNo ratings yet

- On Technology in Innovation Systems and Innovation-Ecosystem Perspectives: A Cross-Linking AnalysisDocument15 pagesOn Technology in Innovation Systems and Innovation-Ecosystem Perspectives: A Cross-Linking AnalysisRonak JoshiNo ratings yet

- Yeji - Yoo 95 107Document13 pagesYeji - Yoo 95 107Phuwadej VorasowharidNo ratings yet

- What governs the transition to a sustainable hydrogen economyDocument19 pagesWhat governs the transition to a sustainable hydrogen economyTodo SimarmataNo ratings yet

- Responsabilidad Social WordDocument29 pagesResponsabilidad Social WordRocio Maria A rojasNo ratings yet

- Effect of Technology On EnviornmentDocument9 pagesEffect of Technology On EnviornmentmeerapradeekrishananNo ratings yet

- Wolsink - 2020 - Framing in Renewable Energy Policies A Glossary-AnnotatedDocument32 pagesWolsink - 2020 - Framing in Renewable Energy Policies A Glossary-AnnotatedhirobeNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Impacts on Science, Tech, and SocietyDocument3 pagesClimate Change Impacts on Science, Tech, and SocietyAngela BronNo ratings yet

- b061 Manas Socio Sem-IIIDocument19 pagesb061 Manas Socio Sem-IIISiddhant KumarNo ratings yet

- Why Are Consumers Going Green - The Role of Environmental Concerns in Private Green-Is Adoption - Kranz Picot 2011Document13 pagesWhy Are Consumers Going Green - The Role of Environmental Concerns in Private Green-Is Adoption - Kranz Picot 2011Cheng Kai WahNo ratings yet

- Technology ControversiesDocument2 pagesTechnology ControversiesMaria MarinovaNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument2 pagesEnglishfred masilaNo ratings yet

- Mazzucato - Mission Oriented Innovation PolicyDocument13 pagesMazzucato - Mission Oriented Innovation PolicyMarco Aurelio DíasNo ratings yet

- Foray & GrublerDocument11 pagesForay & GrublerArchelm Joseph SadangNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 09 01045 v2Document21 pagesSustainability 09 01045 v2Regalado Cereza IIINo ratings yet

- Fisher Midtream ModulationDocument12 pagesFisher Midtream ModulationDiogenes LabNo ratings yet

- Nature IncDocument26 pagesNature IncanahichaparroNo ratings yet

- Morone 2015Document13 pagesMorone 2015Abraham Becerra AranedaNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 - Technology TransferDocument7 pagesTopic 1 - Technology TransferNor Saadiah Mat DaliNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press The Journal of Modern African StudiesDocument33 pagesCambridge University Press The Journal of Modern African StudiesJust BelieveNo ratings yet

- ADF - STIG-Systems - LinkingPolRes&Practice - ResPOL (In Press-Pre-Pub) 2009Document14 pagesADF - STIG-Systems - LinkingPolRes&Practice - ResPOL (In Press-Pre-Pub) 2009Ipsita RoyNo ratings yet

- Business StudiesDocument2 pagesBusiness Studiesfred masilaNo ratings yet

- Geels Et Al (2017)Document17 pagesGeels Et Al (2017)Semangat BelajarNo ratings yet

- Greek Environmetalism: From The Status Nascendi of A Movement To Its Integration1Document36 pagesGreek Environmetalism: From The Status Nascendi of A Movement To Its Integration1ernestofreemanNo ratings yet

- Green Capitalism Accepted 180722Document30 pagesGreen Capitalism Accepted 180722Maximus L MadusNo ratings yet

- Green Automobility: Tesla Motors and The Symbolic Dimensions of "Green Cars"Document88 pagesGreen Automobility: Tesla Motors and The Symbolic Dimensions of "Green Cars"engkos koswaraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Cleaner Production: Teemu Makkonen, Tommi InkinenDocument12 pagesJournal of Cleaner Production: Teemu Makkonen, Tommi InkinenJimmy IoannidisNo ratings yet

- 3370 Yetano RocheDocument39 pages3370 Yetano RocheMuhammad Imran KhanNo ratings yet

- PeterscolesDocument17 pagesPeterscolesNiks Nikhil SharmaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Society Technology and SustainabilityDocument13 pagesContemporary Society Technology and SustainabilityTaukeer KhanNo ratings yet

- TREE-HUGGING STIFLES PUBLIC DEBATEDocument39 pagesTREE-HUGGING STIFLES PUBLIC DEBATENachtFuehrerNo ratings yet

- Role of EnvironmentDocument22 pagesRole of EnvironmentDivesh ChandraNo ratings yet

- Energy Democracy and Social Movements - A Multi-Coalition Perspective OnDocument13 pagesEnergy Democracy and Social Movements - A Multi-Coalition Perspective OnbenkeitheNo ratings yet

- Social Innovation and The Energy Transition: SustainabilityDocument13 pagesSocial Innovation and The Energy Transition: SustainabilityYesica PereaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Science, Technology and Innovation Policy - Old Patterns and New ChallengesDocument28 pages2019 Science, Technology and Innovation Policy - Old Patterns and New ChallengesSYAHIRAH BINTI ROSLINo ratings yet

- Tech Push Pull JeeDocument17 pagesTech Push Pull JeeAzalea CanalesNo ratings yet

- Foray Grübler - Technology and The Environment OverviewDocument14 pagesForay Grübler - Technology and The Environment OverviewAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Energy: Roald A.A. Suurs, Marko P. HekkertDocument11 pagesEnergy: Roald A.A. Suurs, Marko P. Hekkertscorpion2001glaNo ratings yet

- Module in ScienceDocument45 pagesModule in ScienceMark LuceroNo ratings yet

- Energy Democracy As A Process, An Outcome and A Goal: A Conceptual ReviewDocument14 pagesEnergy Democracy As A Process, An Outcome and A Goal: A Conceptual ReviewMario DavilaNo ratings yet

- QUT Digital RepositoryDocument33 pagesQUT Digital RepositoryFernando UribeNo ratings yet

- Eco Politics Beyond The Paradigm of Sustainability A Conceptual Framework and Research AgendaDocument22 pagesEco Politics Beyond The Paradigm of Sustainability A Conceptual Framework and Research AgendaMiriana Partida ZamoraNo ratings yet

- How Do You Feel About The Statement?Document2 pagesHow Do You Feel About The Statement?Juliet ThingsNo ratings yet

- The Dematerialization Potential of Services and It: Futures Studies Methods PerspectivesDocument15 pagesThe Dematerialization Potential of Services and It: Futures Studies Methods PerspectivesRaghav BihaniNo ratings yet

- Temper2018 Article TheGlobalEnvironmentalJusticeADocument12 pagesTemper2018 Article TheGlobalEnvironmentalJusticeAPriscilaNo ratings yet

- TECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIETY: THE INTERRELATED IMPACTSDocument63 pagesTECHNOLOGY, ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIETY: THE INTERRELATED IMPACTSarchiveofdeathNo ratings yet

- CopyrightDocument20 pagesCopyrightdelia_sánchez_26No ratings yet

- Exploring The Organization - Environment Link: Change As CoevolutionDocument15 pagesExploring The Organization - Environment Link: Change As CoevolutionAswini KondaNo ratings yet

- Vergragt, Brown - Innovation For SustainabilityDocument14 pagesVergragt, Brown - Innovation For SustainabilityEduardo DiestraNo ratings yet

- ArchitectureandResilience TrogalPetrescuDocument13 pagesArchitectureandResilience TrogalPetrescuEliasNo ratings yet

- Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and SustainabilityDocument21 pagesLocal Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainabilitytarboleda_1No ratings yet

- IT and Environmental Governance in ChinaDocument14 pagesIT and Environmental Governance in ChinaKaterina TsakmakidouNo ratings yet

- CV of Fawad Mahmeed AhmedDocument3 pagesCV of Fawad Mahmeed AhmedfawadmehmoodNo ratings yet

- Tourism in Transitions: Dieter K. Müller Marek Więckowski EditorsDocument212 pagesTourism in Transitions: Dieter K. Müller Marek Więckowski EditorsraisincookiesNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Management TheoriesDocument19 pagesEvolution of Management Theoriessarwar69No ratings yet

- Dams and BarragesDocument3 pagesDams and BarragesTariq Ahmed0% (1)

- Notice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Bear Butte National Wildlife Refuge, SD Comprehensive Conservation PlanDocument1 pageNotice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Bear Butte National Wildlife Refuge, SD Comprehensive Conservation PlanJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Gri 404 Training and Education 2016Document11 pagesGri 404 Training and Education 2016Pablo MalgesiniNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Runoff in Irrigation EngineeringDocument5 pagesFactors Affecting Runoff in Irrigation EngineeringNilesh AvhadNo ratings yet

- CI LandscapeDocument73 pagesCI LandscapePawanKumarNo ratings yet

- N. Mason Cummings - Indigenous Identity On The World Stage - The Mentawai of IndonesiaDocument8 pagesN. Mason Cummings - Indigenous Identity On The World Stage - The Mentawai of IndonesiaHasriadi Ary MasalamNo ratings yet

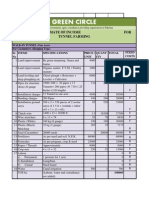

- 0321-8669044 Tunnel Farming in Pakistan Feasibility Walk-In Medium Tunnel 2012 by Green CircleDocument3 pages0321-8669044 Tunnel Farming in Pakistan Feasibility Walk-In Medium Tunnel 2012 by Green CircleSajid Iqbal SandhuNo ratings yet

- DM Plan Jamalpur Sadar Upazila Jamalpur District - English Version-2014Document165 pagesDM Plan Jamalpur Sadar Upazila Jamalpur District - English Version-2014CDMP BangladeshNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument25 pagesReviewerJohn Rey Almeron Serrano100% (1)

- Ojo, Olukayode O. SDocument39 pagesOjo, Olukayode O. SOjo OlukayodeNo ratings yet

- Exhibit 1226-2016.4.27 Joel Gilbert Update To AJE About Tarrant Ramping Down and Expansion To Kingston and Norwood-HighlightedDocument2 pagesExhibit 1226-2016.4.27 Joel Gilbert Update To AJE About Tarrant Ramping Down and Expansion To Kingston and Norwood-HighlightedAnonymous Yxs1MUgNo ratings yet

- Blue GoldDocument125 pagesBlue GoldjamilmelhemNo ratings yet

- Roll Back MalariaDocument2 pagesRoll Back Malariaapi-3705046No ratings yet

- 4 Population 5º Primaria Social ScienceDocument21 pages4 Population 5º Primaria Social SciencevicmasterepubNo ratings yet

- 10 - Factors Effecting OTIFDocument2 pages10 - Factors Effecting OTIFRohit WadhwaniNo ratings yet

- Locus of Control in Who Moved My CheeseDocument2 pagesLocus of Control in Who Moved My CheeseRA OrtizNo ratings yet

- Company Profile MBUDocument59 pagesCompany Profile MBUMandala Bakti UtamaNo ratings yet

- Atty Villa ConchitaDocument3 pagesAtty Villa Conchitanhizza dawn DaligdigNo ratings yet

- Traditional Models For Understanding LeadershipDocument14 pagesTraditional Models For Understanding LeadershipVon Ivan Paz ReyesNo ratings yet