Professional Documents

Culture Documents

03 OT Community Mobility AOTA Exam Prep

Uploaded by

Thirdy BullerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

03 OT Community Mobility AOTA Exam Prep

Uploaded by

Thirdy BullerCopyright:

Available Formats

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

Community Mobility

I. General considerations (Eby et al., 2006; Stav & McGuire, 2012; Womack, 2012;

Womack & Silverstein, 2012)

A. Community mobility: “planning and moving around in the community using public or

private transportation, such as driving, walking, bicycling, or accessing and riding in

buses, taxi cabs, ride shares, or other transportation systems” (American Occupational

Therapy Association [AOTA], 2020; Stav & McGuire, 2012)

B. Forms of community mobility

1. Public transportation: means of moving more than one person at a time from point to point

that is available to all citizens of an area and funded, at least in part, by taxes (Womack &

Silverstein, 2012, p. 28)

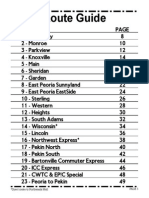

a. Fixed-route transportation: transportation alternatives with a fixed route and schedule for

travel between destinations. Fixed-route transportation is most typically offered in the form

of bus, subway, train, and light rail services.

i. Performance skills required

• Cognitive skills: ability to consider transit options, read a schedule, figure out a route,

calculate the time required to travel to a destination, determine the optimal departure time

to arrive at the destination on time, remember which station to disembark at, and use the

stop-request control at the appropriate time

• Motor and praxis skills: ability to step on and off the vehicle, maintain balance while walking

in a moving vehicle, and maintain postural control while standing or sitting in a moving

vehicle

• Sensory–perceptual skills: ability to identify obstacles on a public vehicle and judge spatial

relationships to identify seats, the stop-request control button, and the gap between the

vehicle and the sidewalk or platform

• Emotional regulation skills: ability to adjust to a crowded versus empty environment and to

handle unexpected events

• Communication and social skills: ability to ask for directions and obtain information

• Money management skills: ability to obtain a monthly pass, have the correct fare ready, and

use the change or ticket machines at the station

ii. Occupational therapy evaluation and intervention

• Assessment in the community setting

• Intervention using both remedial and compensatory strategies to address deficits in each

performance skill area

• Family and caregiver education on use of compensatory strategies

b. Paratransit services: transportation alternatives operated by transit systems for clients

who have functional impairments that limit their access to regular fixed-route services.

Paratransit is most typically offered in the form of van, shuttle, or microbus services that

pick up riders outside their home and take them to specific locations rather than requiring

them to be at a centralized bus stop. Even though some paratransit systems offer

customized assistance, most require that the rider be functionally able to meet the vehicle

at the street (Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 28–29).

i. Performance skills required

Copyright ©1 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

• Cognitive skills: ability to plan and make reservation ahead of time, problem-solving skills

for contingency when a ride does not show or is late, and ability to plan for and adapt to

longer rides

• Motor and praxis skills: ability to get on and off vehicle with limited or no assistance, ability

to get from door to curb without assistance, and sufficient endurance for postural control

during rides

• Sensory–perceptual skills: ability to judge spatial relationships in navigating between the

vehicle and the curb or sidewalk

• Emotional regulation skills: ability to handle unexpected events, such as a no show or late

ride, and longer rides

• Communication and social skills: ability to communicate needs on the telephone to reserve

rides, communicate destination addresses clearly and accurately, and communicate with the

driver about individual needs

• Money management skills: ability to prepare fare or manage tickets

ii. Occupational therapy evaluation and intervention

• Familiarity with policies of the local transit company

• Orientation and assistance to the client in the application process for paratransit

• Assistance with planning for ride reservations and contingency and safety preparations for

longer rides

2. Personal transportation: means of moving about in the community using either one’s own

bodily capacity or vehicular or nonvehicular transportation technology (Womack, 2012, p. CE1;

Womack & Silverstein, 2012, p. 31)

a. Private automobile

b. Other motorized or nonmotorized vehicle (e.g., golf cart, bicycle, scooter, skateboard)

c. Walking and other nonvehicular travel (e.g., running, skiing, skating)

i. Performance skills required for walking

• Cognitive skills: pathfinding ability, including selection of an alternate route when needed;

ability to observe pedestrian safety, such as using the sidewalk, crossing the street at an

intersection with a marked crosswalk, and waiting for the cross signal before crossing; safety

judgment, including checking traffic thoroughly before crossing at an intersection without a

cross signal; and multitasking ability

• Motor and praxis skills: ability to walk on uneven surfaces and inclines, walk around

obstacles, turn head to check traffic and maintain the path on the sidewalk, step up and

down from the curb safely, carry items while navigating with or without use of mobility aids,

cross an intersection within the required time, and maintain sufficient endurance

• Sensory–perceptual skills: ability to identify traffic, judge spatial relationships at the curb

and sidewalk, and maintain topographical orientation

• Emotional regulation skills: ability to adapt to crowded versus empty environments, observe

road safety precautions, and handle unexpected events

• Communication and social skills: ability to multitask in maintaining social conversation and

observing road safety, ask for directions, and observe social etiquette as a pedestrian

ii. Occupational therapy evaluation and intervention for walking

• Assessment in the community setting

• Intervention using both remedial and compensatory strategies to address deficits in each

performance skill area

• Family and caregiver education on use of compensatory strategies

3. Commercial transportation: transportation services operated as for-profit enterprises for which

people pay privately (Womack & Silverstein, 2012, p. 31)

a. Commercial carrier (e.g., airline, train)

Copyright ©2 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

b. Taxi service

c. Shuttle and van service (small-vehicle fleet)

4. Supplemental transportation: volunteer, nonprofit, or community-based transportation options

serving older adults and people with disabilities who either are unable to use existing

transportation services or desire more flexible travel options (Eby et al., 2006, p. 446; Womack

& Silverstein, 2012, pp. 29–31)

a. Senior-friendly supplemental transportation is ideally based on the “Five As”: availability,

acceptability, accessibility, adaptability, and affordability (Womack & Silverstein, 2012, p.

31).

b. Supplemental transportation for seniors is particularly important because most U.S. older

adults who cease driving ride as passengers in private automobiles rather than use public

transportation (Stav, 2008; Womack & Silverstein, 2012).

5. Terms related to paratransit and supplemental transportation (Freund, 2002; ITNAmerica,

n.d.; Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 32–33)

a. Curb-to-curb: Passengers are picked up at the curb of their point of origin and dropped off

at the curb of their destination. Drivers may assist riders with getting on and off the vehicle

but do not assist riders into buildings or with things they are carrying.

b. Door-to-door: Passengers may be assisted from the doorway of their point of origin to the

entrance to their destination but are not assisted to enter.

c. Door-through-door: Passengers may be assisted to exit their travel point of origin and to

enter the building at their destination, as well as on and off the vehicle. This assistance

may be direct physical assistance or assistance with packages.

d. Arm-through-arm: Passengers may be physically assisted by drivers to board, disembark,

and safely reach their final destination (similar to door-through-door, but specifies physical

assistance).

e. Demand-responsive: Transportation is provided between a specific point of origin and

specific destination requested by the traveler. Demand-responsive service travels on a

requested as opposed to a fixed route but may require advance reservations and may or

may not include physical assistance for the client.

C. Legal and political issues related to community mobility

1. Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA; Pub. L. 101-336; Bolding et al., 2018, pp. 260–

262; Koketsu, 2018, pp. 191–192)

a. Established accessibility guidelines for public transportation (e.g., wheelchair lifts in buses,

wheelchair ramps or elevators around facilities)

b. Included guidelines to provide for priority seating, handrails, public address systems to

announce stops, stop-request controls, and clearly marked destination and route signs

(Bolding et al., 2018, p. 260)

c. Established a mandate for complementary paratransit services under Title II

(Transportation)—Part B (U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit

Administration, 2020)

i. Paratransit eligibility criteria: Eligibility for paratransit refers to the determination

that a person, regardless of disability, cannot access fixed-route public transportation

and is therefore eligible for complementary paratransit service. The three categories of

eligibility are (1) inability to navigate the fixed-route transportation system, (2)

unavailability of the public transportation system at the time or place a person with a

Copyright ©3 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

disability needs to travel, and (3) impairment-related inability to board or disembark at

a specific location (Americans With Disabilities Act & Information Technology Technical

Assistance Centers, n.d.).

ii. Determination of paratransit eligibility: Each entity required to provide complementary

paratransit service is required to establish a process for determining ADA paratransit

eligibility. The goal of this process is to ensure that only people who meet the regulatory

criteria, strictly applied, are regarded as eligible. Best practice in eligibility

determination encourages functional assessment of the traveler’s ability to access

transportation resources (Americans With Disabilities Act & Information Technology

Technical Assistance Centers, n.d.).

2. SAFETEA-LU Act: The Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A

Legacy for Users (Pub. L. 109-59) was legislation that funded the Safe Routes to School

program from 2005 to 2012, providing 100% federal funding to facilitate states’ initiatives to

create safe environments surrounding schools and encourage children to bike and walk to

school as part of developing a healthy lifestyle. In 2012 these initiatives were combined with

others as part of the federal Transportation Alternatives Program

(https://www.saferoutespartnership.org/).

3. Medicaid transportation provisions: Recipients of Medicaid may be eligible for subsidized

transportation for health care and life maintenance trips (Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 28–

29).

4. Disparities in availability of public transportation: Fewer than 25% of U.S. rural residents are

served by public transportation (Eby et al., 2006, p. 446).

5. Economics of public transportation

a. The long-term financial viability of public transportation systems might benefit from

investment in training younger people with disabilities to use available services (Precin et

al., 2012).

b. Lack of transportation alternatives for older adults may affect the economy of their

communities when they can no longer easily access local businesses (Freund, 2002; Stav,

2008).

II. Occupational therapy and community mobility

A. Occupational therapy practitioners’ role in addressing community mobility

1. Community mobility as an IADL: The Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and

Process (4th ed.; AOTA, 2020) includes community mobility as an IADL performance area in

the domain of occupational therapy practice to be addressed by occupational therapists and

occupational therapy assistants along with other IADLs (AOTA, 2016, p. 1). Occupational

therapy practitioners are also encouraged to view community mobility as an enabler of other

occupations (Stav & McGuire, 2012, p. 13).

2. Scope of practice: Occupational therapy practitioners across all practice settings should

consider the community mobility needs of their clients (Stav & McGuire, 2012, pp. 1, 13) and

follow a process consistent with that outlined by AOTA (2020) to address community mobility,

including an occupational profile; analysis of occupational performance; intervention planning,

implementation, and review; and determination of outcomes (Stav & McGuire, 2012, p. 11).

B. Assessment of community mobility

Copyright ©4 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

1. Community mobility in the occupational profile: An occupational profile should include

consideration of community mobility relevant to the client and the client’s context, leading to

an analysis of occupational performance. The practitioner should refer clients to a certified

driver rehabilitation specialist for further assessment of driving skills when indicated (Stav &

McGuire, 2012, p. 11; Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 36–37).

2. Assessment of skills and capacities for travel: After completing the occupational profile, the

practitioner continues the evaluation process with measures of client factors, performance

skills, and contexts of the client’s engagement in community mobility to determine areas of

need (Stav & McGuire, 2012, p. 12; Womack, 2012, p. CE3; Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp.

32–33). The same factors that limit the ability to drive may interfere with use of public

transportation (Crabtree et al., 2009).

3. Assessment of Readiness for Mobility Transitions (ARMT): The ARMT (King et al., 2011) is a

means of assessing the readiness of older adults to make transitions regarding their mobility,

such as driving cessation. Understanding how a client perceives transitions in community

mobility allows the practitioner to use the most appropriate approach to address these changes

(Womack & Silverstein, 2012, p. 37).

4. Assessment of the travel context

a. General considerations: AOTA (2016) emphasized the importance of assessing travel

contexts when considering the IADL of community mobility—specifically, analysis of

available transportation options, accessibility of resources, and policy review—as

components of this process.

b. Walkability: extent to which the built environment is pedestrian friendly. Measures are

available in the public domain that occupational therapy practitioners can use to assess

walkability (DiStefano et al., 2012; Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 34, 47).

c. Livability: extent to which a community fulfills principles outlined by the National Council

on Disability (2006) regarding the physical, social, and transportation environments (U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development, n.d.; Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 34–

35).

C. Occupational therapy interventions

1. Addressing community mobility as a generalist: Occupational therapists and occupational

therapy assistants without specialty credentials in driver rehabilitation evaluate and intervene

regarding general community mobility issues and refer clients to certified driver rehabilitation

specialists as indicated (Dickerson, 2012, pp. 419–421; Stav & McGuire, 2012, pp. 11–13).

2. Specific community mobility interventions

a. Travel training: short-term, direct, and intensive training to teach older adults and people

with disabilities to use fixed-route public transportation safely and independently (Womack

& Silverstein, 2012, pp. 33–34)

b. Mobility management: services that promote collaboration and cooperation among

transportation providers and connect clients to those providers (Eby et al., 2006, pp. 444–

454)

c. Systems-level interventions: consultation with transportation systems on issues such as

design of the travel environment for accessibility and creation of eligibility determination

processes for paratransit service (AOTA, 2016; Stav & McGuire, 2012, pp. 13–14)

3. Community mobility challenges with specific populations (AOTA, 2016; McGuire & Davis,

2012)

Copyright ©5 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

a. Older adults (AOTA, 2016; Andonian & McRae, 2011; Classen, 2010; Crabtree et al., 2009;

Stav, 2008; Womack, 2012)

i. Older adults with dementia

• Driving cessation

• Education regarding community mobility alternatives

• Family and caregiver education and support regarding community mobility

ii. Well elderly and community-dwelling older adults

• Education and resources regarding community mobility options

• Maintenance of driving fitness

• Personal safety during community mobility

• Age-related changes in function and intersection with community mobility

iii. Older adults facing driving cessation

• Community mobility alternatives: education, resources

• Psychosocial support

• Travel training

b. Infants and children (AOTA, n.d.; Case-Smith & Arbesman, 2008, p. 422; Heath, Case,

McGuire, & Law, 2007; Sharp, Dunford, & Seddon, 2012; Shutrump, Manary, & Buning,

2008; Stav & McGuire, 2012, pp. 4–5; Womack & Silverstein, 2012, pp. 32, 47)

i. Children who are wheelchair users

• Safe school bus transportation

• Education and support regarding vehicle restraints

• Parent and caregiver education regarding safe community mobility

• Passenger safety

ii. Children with sensory processing disorders (SPD)

• Occupational analysis of the intersection between community mobility and sensory

processing issues

• Education for transportation providers regarding SPD

• Parent and caregiver education and support

• Interventions to assist children with SPD to adapt to community mobility challenges

iii. Parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit

• Passenger safety education

• Education and resources regarding infant car seats

c. People with specific disabling conditions (AOTA, 2016; Atkins, 2014; Benson, 2009;

Crabtree et al., 2009; Eby et al., 2006, pp. 445–446; Hegberg, 2012; Lund et al., 2012;

Precin et al., 2012; U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration,

2020; Wendel et al., 2010)

i. Developmental disabilities (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, intellectual and

developmental disabilities in both children and adults)

• Occupational analysis of community mobility activities and contexts relative to clients’

abilities and performance deficits

• Modification of the community mobility context to match clients’ abilities

• Travel training

• Passenger safety training

• Training and support for transportation entities serving clients with developmental

disabilities

• Opportunities to practice social interactions associated with community mobility

ii. Mental illness

Copyright ©6 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

• Occupational analysis of community mobility activities and contexts relative to clients’

abilities and performance deficits

• Modification of the community mobility context to match clients’ abilities

• Travel training

• Opportunities to practice social interactions associated with community mobility

• Training and support for transportation entities serving clients with mental illness

iii. Spinal cord injury

• Analysis of the sensorimotor demands of community mobility that intersect with clients’

functional presentation

• Determination of community mobility options relative to performance capacities

• Travel training

• Collaboration with transit providers regarding wheelchair safety restraint

iv. Muscular dystrophy

• Occupational analysis of community mobility activities and contexts relative to clients’

abilities and performance deficits

• Modification of the community mobility context to match clients’ abilities

• Travel training

• Passenger safety training

• Training and support for transportation entities serving clients with progressive

neuromuscular conditions

v. Rheumatoid arthritis

• Occupational analysis of community mobility activities and contexts relative to clients’

abilities and performance deficits

• Modification of the community mobility context to match clients’ abilities

• Travel training

• Passenger safety training

• Training and support for transportation entities serving clients with rheumatic conditions

vi. Stroke

• Occupational analysis of community mobility activities and contexts relative to clients’

abilities and performance deficits

• Modification of the community mobility context to match clients’ abilities

• Travel training

• Passenger safety training

• Training and support for transportation entities serving clients with neurological disorders

vii. Cerebral palsy

• Occupational analysis of community mobility activities and contexts relative to clients’

abilities and performance deficits

• Modification of the community mobility context to match clients’ abilities

• Travel training

• Passenger safety training

• Training and support for transportation entities serving clients with cerebral palsy

III. Resources related to community mobility (AOTA, 2016, n.d.; Crabtree et al., 2009;

McGuire & Davis, 2012; Womack, 2012)

A. General resources

1. U.S. Department of Transportation Livability Initiative:

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/livability/index.cfm

2. American Public Transportation Association: https://www.apta.com

Copyright ©7 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

3. America Walks: https://americawalks.org

B. Resources specific to people with disabilities

1. Easter Seals Project Action: https://www.projectaction.com

2. National Council on Disability transportation policy: https://ncd.gov/policy/transportation

3. National Volunteer Transportation Center: https://ctaa.org/national-volunteer-transportation-

center/

C. Resources specific to older adults

1. National Aging and Disability Transportation Center: https://www.nadtc.org/

2. AARP Transportation and Livable Communities: https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/

D. Resources specific to children

1. SafeKids Worldwide: https://safekids.org/

2. National AMBUCS–Amtryke Program: https://ambucs.org/

3. National Center for Safe Routes to School: http://www.saferoutesinfo.org/

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. (n.d.). Teen driving. Retrieved from

http://www.aota.org/practice/children-youth/youth-transportation.aspx

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2016). Driving and community mobility. American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 70(Suppl. 2), 7012410050. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.706S04

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process

(4th ed.) American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. 101-336, 42 U.S.C. § 12101.

Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) & Information Technology Technical Assistance Centers. (n.d.). ADA

transportation series: Paratransit eligibility (draft). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education,

National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

Andonian, L., & McRae, A. (2011). Well older adults within an urban context: Strategies to create and maintain

social participation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74, 2–11.

Atkins, M. S. (2014). Spinal cord injury. In M. V. Radomski & C. A. Trombly Latham (Eds.), Occupational therapy

for physical dysfunction (7th ed., pp. 1168–1214). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Benson, T. (2009). Occupational therapy for adults with sensory processing disorder. OT Practice, 14(10), 15–19.

Bolding, D., Adler, C., Tipton-Burton, M., & Verran, A. (2018). Mobility. In H. M. Pendleton & W. SchultzKrohn

(Eds.), Pedretti’s occupational therapy: Practice skills for physical dysfunction (8th ed., pp. 230–288). St.

Louis, MO: Mosby/Elsevier.

Case-Smith, J., & Arbesman, M. (2008). Evidence-based review of interventions for autism used in or of relevance to

occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 416–429.

https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.62.4.416

Classen, S. (2010). Editorial—Special issue on older driver safety and community mobility. American Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 64, 211–214. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.64.2.211

Crabtree, J., Troyer, J. D., & Justiss, M. D. (2009). The intersection of driving with a disability and being a public

transportation passenger with a disability. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 25, 163–172.

Dickerson, A. (2012). Appendix A: Driving as a valued occupation. In M. J. McGuire & E. S. Davis (Eds.), Driving

and community mobility: Occupational therapy strategies across the lifespan (pp. 417–422). Bethesda, MD:

AOTA Press.

Copyright ©8 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

AOTA’s NBCOT® Exam Prep

Di Stefano, M., Stuckey, R., & Lovell, R. (2012). Promotion of safe community mobility: Challenges and

opportunities for occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 59, 98–102.

Eby, D. W., Molnar, L. J., & Pellerito, J. M. (2006). Driving cessation and alternative community mobility. In J. M.

Pellerito, Jr. (Ed.), Driver rehabilitation and community mobility (pp. 444–454). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Freund, K. (2002). Pilot testing innovative payment operations for independent transportation network:

Transportation for the elderly (Final rep., Transit–IDEA Project No. 18). Washington, DC: Transportation

Research Board.

Heath, T., Case, T., McGuire, B., & Law, M. (2007). Successful participation: The lived experience among children

with disabilities. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74, 38–47.

Hegberg, A. (2012). Use of adaptive equipment to compensate for impairments in motor performance skills and

client factors. In M. J. McGuire & E. S. Davis (Eds.), Driving and community mobility: Occupational therapy

strategies across the lifespan (pp. 279–320). Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press.

ITNAmerica. (n.d.). What we do. Retrieved from http://www.itnamerica.org/what-we-do

King, M. D., Meuser, T. M., Berg-Weger, M., Chibnall, J. C., Harmon, A., & Yakimo, R. (2011). Decoding the Miss

Daisy syndrome: An examination of subjective responses to mobility changes. Journal of Gerontological

Social Work, 54, 29–52.

Koketsu, J. S. (2018). Activities of daily living. In H. M. Pendleton & W. Schultz-Krohn (Eds.), Pedretti’s

occupational therapy: Practice skills for physical dysfunction (8th ed., pp. 155–229). St. Louis, MO:

Mosby/Elsevier.

Lund, A., Michelet, M., Kjeken, I., Wyller, T. B., & Sveen, U. (2012). Development of a person-centred lifestyle

intervention for older adults following a stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Scandinavian Journal of

Occupational Therapy, 19, 140–149.

McGuire, M. J., & Davis, E. S. (Eds.). (2012). Driving and community mobility: Occupational therapy strategies

across the lifespan. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press.

National Council on Disability. (2006). Creating livable communities. Retrieved from

https://www.ncd.gov/publications/2006/Oct312006

Precin, P., Otto, M., Popalzai, K., & Samuel, M. (2012). The role for occupational therapists in community mobility

training for people with autism spectrum disorders. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 28, 129–146.

Sharp, N., Dunford, C., & Seddon, L. (2012). A critical appraisal of how occupational therapists can enable

participation in adapted physical activity for children and young people. British Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 75, 486–494.

Shutrump, S. E., Manary, M., & Buning, M. E. (2008). Safe transportation for students who use wheelchairs on the

school bus. OT Practice, 13(15), 8–12.

Stav, W. B. (2008). Review of the evidence related to older adult community mobility and driver licensure policies.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 149–158. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.62.2.149

Stav, W. B., & McGuire, M. J. (2012). Introduction to community mobility and driving. In M. J. McGuire & E. S.

Davis (Eds.), Driving and community mobility: Occupational therapy strategies across the lifespan (pp. 1–18).

Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). Six livability principles. Retrieved from

https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/economic_development/Six_Livability_Principles

U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. (2020). ADA guidance. Retrieved from

https://www.transit.dot.gov/regulations-and-guidance/civil-rights-ada/ada-guidance

Wendel, K., Stahl, A., Risberg, J., Pessah-Rasmussen, H., & Iwarsson, S. (2010). Post-stroke functional limitations

and changes in use of mode of transport. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 17, 162–174.

Womack, J. L. (2012). Continuing life on the move: Aging and community mobility. OT Practice, 17(3), CE1–CE8.

Womack, J. L., & Silverstein, N. M. (2012). The big picture: Comprehensive community mobility options. In M. J.

McGuire & E. S. Davis (Eds.), Driving and community mobility: Occupational therapy strategies across the

lifespan (pp. 19–47). Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press.

Copyright ©9 2020 by the American Occupational Therapy Association. All

rights reserved. For permissions, contact www.copyright.com.

You might also like

- JTA FY 23-24 Budget For IA PacketDocument26 pagesJTA FY 23-24 Budget For IA PacketActionNewsJaxNo ratings yet

- Family ResourcesDocument33 pagesFamily ResourcesJackie S LaymanNo ratings yet

- OIG Investigation 2018-0005: Palm Tran - Contractor Maruti Fleet & Management, LLCDocument111 pagesOIG Investigation 2018-0005: Palm Tran - Contractor Maruti Fleet & Management, LLCSabrina LoloNo ratings yet

- WMATA Report by McKinsey CompanyDocument89 pagesWMATA Report by McKinsey CompanyReginald BazileNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia Accessibility GuidelinesDocument242 pagesSaudi Arabia Accessibility GuidelinesihabosmanNo ratings yet

- Travel Demand ForecastingDocument54 pagesTravel Demand ForecastingKristelle Ginez100% (1)

- Urban Transportation PlanningDocument42 pagesUrban Transportation Planningmonika hcNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 - Travel Demand Forecasting: Transportation PlanningDocument40 pagesLecture 2 - Travel Demand Forecasting: Transportation PlanningEngr mehraj hameedNo ratings yet

- Lecture 23. Basics of Transportation PlanningDocument44 pagesLecture 23. Basics of Transportation PlanningRatsel Isme100% (1)

- From Mobility to Accessibility: Transforming Urban Transportation and Land-Use PlanningFrom EverandFrom Mobility to Accessibility: Transforming Urban Transportation and Land-Use PlanningNo ratings yet

- Accessible Transportation and Mobility: S. LING SUEN, Transportation Development Centre, Transport CanadaDocument25 pagesAccessible Transportation and Mobility: S. LING SUEN, Transportation Development Centre, Transport Canadagoswami3035969No ratings yet

- Definition of A Behavioural ModelDocument7 pagesDefinition of A Behavioural ModelAnishish SharanNo ratings yet

- NXILg Esb O1Document11 pagesNXILg Esb O1nissy jessilynNo ratings yet

- CE123-2 - Travel Demand Forecasting Technique Part 2Document67 pagesCE123-2 - Travel Demand Forecasting Technique Part 2Thirdy HummingtonNo ratings yet

- Walkability, Accessibility & Safety Audits: Ensuring Last Mile ConnectivityDocument8 pagesWalkability, Accessibility & Safety Audits: Ensuring Last Mile ConnectivityReshma GeorgiNo ratings yet

- Prelim NotesDocument14 pagesPrelim Notesqjlpanizales1No ratings yet

- Requirements of Facilities Road Transportation For Disabilities MobilityDocument20 pagesRequirements of Facilities Road Transportation For Disabilities MobilityrayhanNo ratings yet

- How To Conduct Poverty, Social and Gender Analysis For TransportDocument11 pagesHow To Conduct Poverty, Social and Gender Analysis For TransportADBGADNo ratings yet

- Assignment No: 01Document8 pagesAssignment No: 01waqasNo ratings yet

- How Better Measurement Can Improve Transportation Equity in Underserved Communities Webinar Notes JUN272022Document9 pagesHow Better Measurement Can Improve Transportation Equity in Underserved Communities Webinar Notes JUN272022Savannah GilNo ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument11 pagesReviewerBryant Joseph Tugcay VelascoNo ratings yet

- Why Gender and TransportDocument20 pagesWhy Gender and TransportADBGADNo ratings yet

- Trans Options For Older AdultsDocument6 pagesTrans Options For Older AdultsNoviaSuryadwantiNo ratings yet

- Cete 47Document20 pagesCete 47jananiNo ratings yet

- Transportation Planning - Part 6-10Document33 pagesTransportation Planning - Part 6-10adnan qadirNo ratings yet

- NMT Study in VijayawadaDocument10 pagesNMT Study in VijayawadaPavani SingamsettyNo ratings yet

- CEE 6505: Transportation PlanningDocument73 pagesCEE 6505: Transportation PlanningRifat Hasan100% (1)

- A Case Study Passenger Ergonomics in Public Buses in Kolkata..Document25 pagesA Case Study Passenger Ergonomics in Public Buses in Kolkata..MURARI MOHAN MANNA100% (1)

- 06 Handout 1Document9 pages06 Handout 1Kurty GaliasNo ratings yet

- TRB'14 ApplicationAutonomousDrivingTechnologytoTransit LutinKornhauserDocument39 pagesTRB'14 ApplicationAutonomousDrivingTechnologytoTransit LutinKornhauserwoodNo ratings yet

- Research DocumentationDocument58 pagesResearch Documentationapi-468315946No ratings yet

- R3-Commuter-Guide-Transpo-CHAPTER 1-2Document42 pagesR3-Commuter-Guide-Transpo-CHAPTER 1-2Angelina NicdaoNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document31 pagesModule 1Aldrin CruzNo ratings yet

- Fce 545 Chapter 1Document26 pagesFce 545 Chapter 1VICTOR MWANGINo ratings yet

- D 64 B CFC CarpoolingDocument13 pagesD 64 B CFC Carpoolingproject missionNo ratings yet

- DSIT - Gender Analysis and Gender Action Plans in Transport ProjectsDocument25 pagesDSIT - Gender Analysis and Gender Action Plans in Transport ProjectsAsian Development Bank - TransportNo ratings yet

- R2 Commuter Guide Transpo CHAPTER 1 2 1Document44 pagesR2 Commuter Guide Transpo CHAPTER 1 2 1Angelina NicdaoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Transportation EngineeringDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Transportation EngineeringSelino CruzNo ratings yet

- The Acceptance Perceptions Autonomous CarsDocument14 pagesThe Acceptance Perceptions Autonomous CarswadelrayahNo ratings yet

- Transportation EngineeringDocument3 pagesTransportation EngineeringCHRISTIAN F. MAYUGANo ratings yet

- R1 Commuter Guide Transpo CHAPTER 1Document25 pagesR1 Commuter Guide Transpo CHAPTER 1Angelina NicdaoNo ratings yet

- Class Project DiscussionDocument27 pagesClass Project DiscussionHari PNo ratings yet

- محاضرة رقم 6Document20 pagesمحاضرة رقم 6Zainab A. AbdulstaarNo ratings yet

- LEC 1 Transportation PlanningDocument19 pagesLEC 1 Transportation PlanningEng. victor kamau NjeriNo ratings yet

- Travel Mode ChoiceDocument21 pagesTravel Mode ChoiceJohaimah MacatanongNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document66 pagesChapter 3Yoni RebumaNo ratings yet

- Subject: Transport Economics Chapter Title: Travel Demand AnalysisDocument25 pagesSubject: Transport Economics Chapter Title: Travel Demand AnalysisIrfan ShinwariNo ratings yet

- Highwy PLANNINGDocument102 pagesHighwy PLANNINGadnan qadirNo ratings yet

- Transportation System ComponentsDocument3 pagesTransportation System Componentsliezyl MantaringNo ratings yet

- FINAL MDOT Ped Crosswalk Guide March 2020Document22 pagesFINAL MDOT Ped Crosswalk Guide March 2020Herminio Lagran CarinoNo ratings yet

- 4 Step ModellingDocument7 pages4 Step ModellingAcharya AnirudhNo ratings yet

- Chibbs Accessibility AssignmentDocument19 pagesChibbs Accessibility AssignmentGeylord GoweroNo ratings yet

- Ce18 L1 012824 CVMDocument4 pagesCe18 L1 012824 CVMKATHLEEN CASTRONo ratings yet

- Transportation Planning II Comprehensive Transportation Planning ProcessDocument19 pagesTransportation Planning II Comprehensive Transportation Planning ProcessEng. victor kamau NjeriNo ratings yet

- America Needs Complete Streets: Mobility. When We Focus On Mobility, FastDocument8 pagesAmerica Needs Complete Streets: Mobility. When We Focus On Mobility, FastINGVIASNo ratings yet

- I. Value Proposition:: To RidersDocument7 pagesI. Value Proposition:: To Ridersmanav chetwaniNo ratings yet

- Supplimentary InformationDocument4 pagesSupplimentary InformationTed WatkinsNo ratings yet

- 16 Cdi 4Document5 pages16 Cdi 4mirameee131No ratings yet

- Latitude & Next American City - Tech For Transit: Designing A Future System (Study Summary)Document9 pagesLatitude & Next American City - Tech For Transit: Designing A Future System (Study Summary)LatitudeNo ratings yet

- Planning of Transportation SystemsDocument11 pagesPlanning of Transportation SystemsMike WheazzyNo ratings yet

- TAC 26 Module 5 S1 26may2021 MSGN RevDocument117 pagesTAC 26 Module 5 S1 26may2021 MSGN RevAPRIL ROSE Placer GaleonNo ratings yet

- CE 3213 - First AssignmentDocument9 pagesCE 3213 - First AssignmentJulrey Angelo SedenoNo ratings yet

- Transportation Planning and Modelling: Muhammad Zudhy Irawan Zudhyirawan - Staff.ugm - Ac.idDocument15 pagesTransportation Planning and Modelling: Muhammad Zudhy Irawan Zudhyirawan - Staff.ugm - Ac.idMohamed Ali SalemNo ratings yet

- Chapter 01Document4 pagesChapter 01Patrick Jamiel TorresNo ratings yet

- Transportation Demand AnalysisDocument4 pagesTransportation Demand AnalysisLawiswisNo ratings yet

- Willamette Pedestrian Coalition: Annual ReportDocument4 pagesWillamette Pedestrian Coalition: Annual ReportStephanie RouthNo ratings yet

- Jta TDP 2019 2029Document786 pagesJta TDP 2019 2029county_guvNo ratings yet

- Neumann Andreas PDFDocument267 pagesNeumann Andreas PDFAnonymous EnrdqTNo ratings yet

- An Integration Model For Car Sharing and Public Transport: Case of IstanbulDocument10 pagesAn Integration Model For Car Sharing and Public Transport: Case of IstanbulNelson RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Emerging Role of Bike (Motorcycle) Taxis in Urban Mobility: Discussion PaperDocument28 pagesEmerging Role of Bike (Motorcycle) Taxis in Urban Mobility: Discussion PaperSankalp GahlotNo ratings yet

- Capital Area Transit 2014Document6 pagesCapital Area Transit 2014PennLiveNo ratings yet

- Integrated Multi-Modal Transportation System (IMMTS)Document19 pagesIntegrated Multi-Modal Transportation System (IMMTS)vinay dhingraNo ratings yet

- Optimal Transport System For Owerri CityDocument10 pagesOptimal Transport System For Owerri Citydonafutow2073No ratings yet

- Socio Cultural CentreDocument3 pagesSocio Cultural CentreDesign draftNo ratings yet

- Attachment A - OrdinanceDocument36 pagesAttachment A - OrdinanceMetro Los AngelesNo ratings yet

- Article 3 - Towards and Inclusive Public Transport in PakistanDocument12 pagesArticle 3 - Towards and Inclusive Public Transport in PakistanShoaib MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Utp 1 & 2 ModuleDocument36 pagesUtp 1 & 2 ModuleMeghana100% (4)

- Hawaii County Settlement AgreementDocument21 pagesHawaii County Settlement AgreementHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNo ratings yet

- Metro Board of Directors April 2019 AgendaDocument20 pagesMetro Board of Directors April 2019 AgendaMetro Los AngelesNo ratings yet

- Jennings, G, y Behrens, R. - The Case For Investing in Paratransit. Strategies and Regulation and Reform.Document29 pagesJennings, G, y Behrens, R. - The Case For Investing in Paratransit. Strategies and Regulation and Reform.Mireya MoralesNo ratings yet

- Inktel Broward County Transit-Rfp 1 2Document150 pagesInktel Broward County Transit-Rfp 1 2api-261615143No ratings yet

- KCATA KCMO Contract 2023 2024 ATA Signed June 28 2023 With Attachments-SignedDocument32 pagesKCATA KCMO Contract 2023 2024 ATA Signed June 28 2023 With Attachments-SignedThe Kansas City StarNo ratings yet

- Final 2021 2024 Coordinated Public Transit PlanDocument63 pagesFinal 2021 2024 Coordinated Public Transit PlanMetro Los AngelesNo ratings yet

- The PlanDocument82 pagesThe PlanMetro Los AngelesNo ratings yet

- Pace ADA Paratransit Service: City of Chicago Customer GuideDocument22 pagesPace ADA Paratransit Service: City of Chicago Customer GuideKCNo ratings yet

- Ecolane Helsinki FactsDocument1 pageEcolane Helsinki FactsAntti HannulaNo ratings yet

- 3-20-17 Draft MBTA Strategic PlanDocument50 pages3-20-17 Draft MBTA Strategic Plantali_bergerNo ratings yet

- DDOT Paratransit LetterDocument1 pageDDOT Paratransit Letterbrandon carrNo ratings yet

- Utp Module 01 PPT NotesDocument102 pagesUtp Module 01 PPT NotesYogeshNo ratings yet

- CityLink Peoria Rider's GuideDocument48 pagesCityLink Peoria Rider's GuideatiqorinNo ratings yet