Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tan Emj, Yeong YQ, Quah JLJ Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital

Uploaded by

Farman ullahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tan Emj, Yeong YQ, Quah JLJ Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital

Uploaded by

Farman ullahCopyright:

Available Formats

Emergency and Disaster Preparedness amongst

Emergency Medicine Residents in Singapore

Tan Yeong Quah EMJ ,

1 YQ ,

1 JLJ1

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital

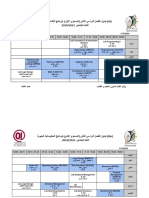

Domain (number of Overall Junior Senior Difference of means

Introduction: Disasters are increasingly prevalent in today’s world, questions) response, Residents, Residents, (95% CI), p

from natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina, to mass shootings, Mean (± SD) Mean (± SD) Mean (± SD)

to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Locally in Singapore, this (N=37) (N=28) (N=9)

1. Detection and 2.81 (±0.82) 2.74 (±0.83) 3 (±0.81) -0.26 (-0.90,0.38)

included the collapse of Hotel New World in 1986, the Nicoll

Response to an Event p = 0.423

Highway Collapse in 2004, and the Shell Refinery fires in 2011 and (6)

2015. Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians are often first 2. The incident 2.53 (±0.93) 2.43 (±0.94) 2.85 (±0.88) -0.41 (-1.14,0.31)

responders and leaders of the disaster medical response. Therefore, command system (ICS) p= 0.253

and your role within it

it is important for EM Residents to have the requisite knowledge. (8)

This study aims to assess the level of preparedness and attitudes 3. Ethical issues in 2.84 (±0.79) 2.71 (±0.82) 3.22 (±0.57) -0.51 (-1.11,0.09)

towards disaster medicine amongst EM Residents in Singapore. triage (4) p=0.093

4. Epidemics and 2.49 (±0.99) 2.43 (±0.99) 2.67 (±1.05) -0.24 (-1.02,0.54)

Surveillance (4) p= 0.54

Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed with residents 5. Isolation/ Quarantine 2.91 (±1.05) 2.82 (±1.10) 3.17 (±0.90) -0.35 (-1.17,0.48)

enrolled in EM Residency Programmes in Singapore (Academic Year (2) p = 0.4

6. Decontamination (3) 2.88 (±0.93) 2.83 (±0.98) 3.03 (±0.79) -0.20 (-0.93,0.53)

2020/2021). A self-administered, 44-item online questionnaire p = 0.575

based on the Emergency Preparedness Information Questionnaire 7. Communication/ 2.54 (±0.90) 2.42 (±0.89) 2.90 (±0.86) -0.48 (-1.17,0.21)

(EPIQ) was delivered via the online GoogleFormsTM platform. This Connectivity (7) p = 0.164

assessed familiarity through 10 dimensions as well as attitudes 8. Psychological Issues 2.34 (±0.95) 2.37 (±0.97) 2.25 (±0.95) 0.12 (-0.63,0.87)

(4) p = 0.755

towards emergency preparedness and preferred learning methods. 9. Special Populations 2.53 (±0.95) 2.41 (±0.97) 2.89 (±0.82) -0.48 (-1.21,0.26)

Data was collected from May 2020 to November 2020. The (2) p = 0.193

Emergency Preparedness Information Questionnaire was initially 10. Accessing Critical 2.28 (±0.93) 2.19 (±0.89) 2.56 (±0.82) -0.37 (-1.09,0.36)

Resources (3) p = 0.311

developed by the Wisconsin Health Alert Network, to assess nurses’

Overall familiarity with 2.60 (±0.82) 2.52 (±0.83) 2.85 (±0.76) -0.33 (-0.96, 0.01),

self-reported familiarity with emergency preparedness, in 2004. It disaster preparedness p = 0.302

has since been externally validated and is widely used to survey (calculated)

healthcare professionals. Overall familiarity with 2.43 (±0.90) 2.36 (±0.95) 2.67 (±0.71) -0.31 (-1.01,0.39)

disaster preparedness p = 0.376

(reported)

Results

Discussion: Limitations included small sample size due to the response rate

• 37/90 (41%) residents responded; 28 (75%) were Junior of 37 residents (41%). Questionnaires had been planned to be distributed

Residents (JR) and the remainder Senior Residents (SR). at face-to-face combined teachings which might have increased the

• For overall familiarity with disaster preparedness, the overall response rate; however due to COVID restrictions, this pivoted to online

calculated mean knowledge score was 2.60 (±0.82), and the platforms. Additionally, as anonymity was ensured, it was not possible to

mean self-reported knowledge score was 2.43 (±0.90). compare which cluster the participants came from; this may have led to

unequal distribution across Residency clusters. Hence, the study was held

• There was no statistically significant difference in overall

over a few months, in order to increase the response rate and obtain more

calculated or self-reported familiarity with disaster preparedness accurate representation. The COVID pandemic was also ongoing during the

between JRs and SRs. study, hence the residents’ attitudes as well as knowledge of emergency

• There was no significant difference in overall familiarity between preparedness may have been affected by the evolution of the pandemic.

the 17% (45) participants who participated in ≥1 course

compared to those who attended none; mean difference 0.288 (- Conclusion: Currently, EM Residents have a poor overall (mean 2.60 ±0.82)

0.314, 0.891), p=0.338. and self-reported (mean 2.43 ±0.90) familiarity with regards to emergency

• Residents felt that disaster medicine was relevant to their preparedness, however they recognized its importance and relevance. Of

the 10 competency dimensions, lower scoring areas included how to access

practice and that it was necessary to learn more about it; mean

critical resources and psychological issues. More focus could be put into

of 4.22 (±0.98) and 4.16 (±0.90) respectively.

teaching these areas. The most preferred learning format was

• The highest ranked learning method was workshop/simulation simulation/workshop training. The challenge of conducting face-to-face

training (45.5%), followed by lectures (23.4%). training during the pandemic necessitated virtual workshops and training,

and more research is needed in this area.

References

1. Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) and United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Human cost of disasters: an overview of the last 20 years (2000-2019). CRED

and UNDRR; 2020.

2. Wisniewski R, Dennik-Champion G, Peltier JW. Emergency preparedness competencies: assessing nurses' educational needs. J Nurs Adm 2004;34(10):475-80.

3. Murphy JP, Radestad M, Kurland L, et al. Emergency department registered nurses' disaster medicine competencies. An exploratory study utilizing a modified Delphi technique. Int Emerg Nurs 2019;43:84-

91.

4. Franc JM, Nichols D, Dong SL. Increasing emergency medicine residents' confidence in disaster management: use of an emergency department simulator and an expedited curriculum. Prehosp Disaster Med

2012;27(1):31-5.doi: 10.1017/S1049023X11006807.

5. Sarin RR, Cattamanchi S, Alqahtani A, et al. Disaster education: a survey study to analyze disaster medicine training in emergency medicine residency programs in the United States. Prehosp Disaster Med

2017;32(4):368-373.

6. Cornelius AP, Andress WK, Ajayi R, et al. What and how are EM residents being taught to respond to the next disaster? Am J Disaster Med 2018;13(4):279-287.

7. Ngo J, Schertzer K, Harter P, et al. Disaster medicine: a multi-modality curriculum designed and implemented for emergency medicine residents. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2016;10(4):611-4.

8. Alexander AJ, Bandiera GW, Mazurik L. A multiphase disaster training exercise for emergency medicine residents: opportunity knocks. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12(5):404-9.

9. Hansoti B , Kellogg DS , Aberle SJ , et al. Preparing emergency physicians for acute disaster response: a review of current training opportunities in the US. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2016;31(6):643–647.

10. Curtis HA, Trang K, Chason KW, et al. video-based learning vs traditional lecture for instructing emergency medicine residents in disaster medicine principles of mass triage, decontamination, and personal

protective equipment. Prehosp Disaster Med 2018;33(1):7–12.

11. Grock A, Aluisio AR, Abram E, et al. Evaluation of the association between disaster training and confidence in disaster response among graduate medical trainees: a cross-sectional study. Am J Disaster Med

2017;12:5-9.

You might also like

- Checlist Compensación de LivingstonDocument8 pagesCheclist Compensación de LivingstonJULIANo ratings yet

- 9230 Mark Scheme 1 International Geography Jun22Document26 pages9230 Mark Scheme 1 International Geography Jun22SikkenderNo ratings yet

- Parent Child RelationshipDocument8 pagesParent Child RelationshipHUSSAINA BANONo ratings yet

- Informative Speech TextDocument2 pagesInformative Speech TextadzwinjNo ratings yet

- AEOO Poster Presentation - Uma MageswariDocument1 pageAEOO Poster Presentation - Uma MageswariUma MageswariNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa2027278 AppendixDocument17 pagesNejmoa2027278 AppendixJohn NinNo ratings yet

- GUJCET2016T05 SolutionDocument11 pagesGUJCET2016T05 SolutionvuppalasampathNo ratings yet

- Simulation of Diffuse Optical Tomography Using COMSOL MultiphysicsDocument11 pagesSimulation of Diffuse Optical Tomography Using COMSOL MultiphysicsNgôn NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Iatrogenic ParesthesiaDocument6 pagesIatrogenic Paresthesiashobhana20No ratings yet

- 2017 June - Unit 2 Mark SchemeDocument13 pages2017 June - Unit 2 Mark SchemeJovian AlvinoNo ratings yet

- OpticsDocument21 pagesOpticsAquib JavedNo ratings yet

- Tear Film Lipid Layer Increase After Diquafosol Instillation in Dry Eye Patients With Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: A Randomized Clinical StudyDocument10 pagesTear Film Lipid Layer Increase After Diquafosol Instillation in Dry Eye Patients With Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: A Randomized Clinical StudyElfrida RianiNo ratings yet

- MethodologyDocument11 pagesMethodologyCatalin BarbuNo ratings yet

- Occupational Eye InjuryDocument4 pagesOccupational Eye InjurynafisahNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Report 10 Drag On A Sphere 2Document16 pagesLaboratory Report 10 Drag On A Sphere 2djn28gd2j2No ratings yet

- Wave Opticslllln.Document29 pagesWave Opticslllln.jumb oNo ratings yet

- Confidence Interval EstimationDocument31 pagesConfidence Interval EstimationSaurabh Sharma100% (1)

- CWTS 11 Disaster Risk Reduction and Management 2022Document130 pagesCWTS 11 Disaster Risk Reduction and Management 2022Kurt AndicoyNo ratings yet

- Httpsadelantelms - Usjr.edu - Phcontentenforced42766 FirstSem2023 17001CWTS201120 20Disaster20Risk20Reduction20and20Ma 5Document111 pagesHttpsadelantelms - Usjr.edu - Phcontentenforced42766 FirstSem2023 17001CWTS201120 20Disaster20Risk20Reduction20and20Ma 5Jenn TajanlangitNo ratings yet

- جدول البرامج الخاصة - رمضانDocument7 pagesجدول البرامج الخاصة - رمضانmahmoud.badry100No ratings yet

- Orthokeratology Review and UpdateDocument21 pagesOrthokeratology Review and Updatem shoshanNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Criteria Template (MDR)Document2 pagesRisk Management Criteria Template (MDR)Lorena AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1.: N C DK DWDocument10 pagesAssignment 1.: N C DK DWjuNo ratings yet

- Lec-5 Sep 22, 2021Document20 pagesLec-5 Sep 22, 2021Muhammad Noor WaliNo ratings yet

- Subjectivity in Conventional Risk Measures: An Attempt To Minimise Bias in Value-at-Risk & Expected ShortfallDocument14 pagesSubjectivity in Conventional Risk Measures: An Attempt To Minimise Bias in Value-at-Risk & Expected ShortfallDeb MajNo ratings yet

- 2019.11.24 Seminar 3Document15 pages2019.11.24 Seminar 3Anna NurachmawatiNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgD K2syqYdzGmMfJF - lPyYf1oVfDjphAwuk7P0lWGdwFXbdZIXMsQ7 HfsuH81sXgPMFWyGUV41UU0auphmaWXZtBQ1hobRRQO0LE Zzowz3DZwbwR1KIXH GEDocument26 pagesACFrOgD K2syqYdzGmMfJF - lPyYf1oVfDjphAwuk7P0lWGdwFXbdZIXMsQ7 HfsuH81sXgPMFWyGUV41UU0auphmaWXZtBQ1hobRRQO0LE Zzowz3DZwbwR1KIXH GEPriscilla Bandeira FrotaNo ratings yet

- Bioassay Procedure For Three Point and Four PointDocument17 pagesBioassay Procedure For Three Point and Four PointLokesh MahataNo ratings yet

- Sampling Principles: Reference ManualDocument10 pagesSampling Principles: Reference ManualgaboNo ratings yet

- Resuscitation: Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest During The COVID-19 Pandemic in The Province of Padua, Northeast ItalyDocument3 pagesResuscitation: Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest During The COVID-19 Pandemic in The Province of Padua, Northeast ItalyEswari PerisamyNo ratings yet

- Nter Olecular Orces (IMF) : Saptarshi MajumdarDocument23 pagesNter Olecular Orces (IMF) : Saptarshi MajumdarPrateek ChandraNo ratings yet

- Code-A: Regd. Office: Aakash Tower, 8, Pusa Road, New Delhi-110005 PH.: 011-47623456Document15 pagesCode-A: Regd. Office: Aakash Tower, 8, Pusa Road, New Delhi-110005 PH.: 011-47623456rhevaNo ratings yet

- Ang-2aslph C1 21-22Document2 pagesAng-2aslph C1 21-22Bouch NoureNo ratings yet

- Online National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (ONEISS) FactsheetDocument14 pagesOnline National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (ONEISS) FactsheetOliVerNo ratings yet

- Milestone Test Practice by Lavish SirDocument15 pagesMilestone Test Practice by Lavish Sirprakashsinghsatya448No ratings yet

- Van Ben Schoten 1995Document8 pagesVan Ben Schoten 1995Brent WoottonNo ratings yet

- January 2022 (IAL) MSDocument8 pagesJanuary 2022 (IAL) MSKalkidan EstifanosNo ratings yet

- Urinary Diversion After Radical Cystectomy Ileal Conduit or Transuretero-Cutaneostomy?Document1 pageUrinary Diversion After Radical Cystectomy Ileal Conduit or Transuretero-Cutaneostomy?Indra JayaNo ratings yet

- The Disc Damage Likelihood Scale PDFDocument6 pagesThe Disc Damage Likelihood Scale PDFsolsito13No ratings yet

- Ppe 39Document3 pagesPpe 39Sajin AlexanderNo ratings yet

- DPP-21 - Wave OpticsDocument4 pagesDPP-21 - Wave OpticsPpoNo ratings yet

- Two-Way Tables - Measures of AssociationDocument33 pagesTwo-Way Tables - Measures of AssociationPacino AlNo ratings yet

- Accuracy and UncertaintiesDocument35 pagesAccuracy and UncertaintiesAlvaro Rodrigo Oporto CauzlarichNo ratings yet

- Fortnightly Test SeriesDocument13 pagesFortnightly Test SeriesDebarjun Halder100% (2)

- High Risk Pregnancy Atsm 2018Document39 pagesHigh Risk Pregnancy Atsm 2018yuastikapsNo ratings yet

- Last Leap For NEET-2020 (Part-II) - Phy - Zoo - CombineDocument520 pagesLast Leap For NEET-2020 (Part-II) - Phy - Zoo - CombineSANJOY KUMAR BHATTACHARYYA100% (1)

- Original: Evaluation of Effective Sources in Uncertainty Measurements of Personal Dosimetry by A Harshaw TLD SystemDocument6 pagesOriginal: Evaluation of Effective Sources in Uncertainty Measurements of Personal Dosimetry by A Harshaw TLD SystemMuhammad AgungNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Week 2: Assignment 2Document4 pagesUnit 3 - Week 2: Assignment 2Sparsh ShukalNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 81449Document9 pages2021 Article 81449Susan AriasNo ratings yet

- High Risk Pregnancy Atsm 2018Document37 pagesHigh Risk Pregnancy Atsm 2018Andrian drsNo ratings yet

- STAT Module-1: Summarizing: One Variable and Relationship Between Two Variables Pr. Tounkara January 18, 2022Document39 pagesSTAT Module-1: Summarizing: One Variable and Relationship Between Two Variables Pr. Tounkara January 18, 2022expertDiedhiouNo ratings yet

- ATLS-9e Trauma Scores PDFDocument3 pagesATLS-9e Trauma Scores PDFWaeel HamoudaNo ratings yet

- CH10 習題解答Document67 pagesCH10 習題解答sapphira0817No ratings yet

- Facility-Onset Infections(s) Device-Or Care-Related: Clostridioides DifficileDocument2 pagesFacility-Onset Infections(s) Device-Or Care-Related: Clostridioides DifficileHeba HanyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 Decision AnalysisDocument14 pagesChapter 8 Decision Analysisapi-25888404No ratings yet

- Fe Statistics ReviewDocument66 pagesFe Statistics Reviewfem mece3381No ratings yet

- NBTS 01 (2021)Document21 pagesNBTS 01 (2021)9459 HUSAINA MONINo ratings yet

- Tabel 1. Proporsi Pasien Sembuh Dari A. Lumbricoides Dengan Terapi Dosis Tunggal Tablet Kunyah Lepas Cepat Mebendazole 500 MG Dibandingkan PlaceboDocument5 pagesTabel 1. Proporsi Pasien Sembuh Dari A. Lumbricoides Dengan Terapi Dosis Tunggal Tablet Kunyah Lepas Cepat Mebendazole 500 MG Dibandingkan PlaceboAdam MuhammadNo ratings yet

- 6 EstimationDocument28 pages6 EstimationesmaelNo ratings yet

- Research AssignmentDocument8 pagesResearch AssignmentAbdusalam IdirisNo ratings yet

- Datasheet PLD ComecDocument7 pagesDatasheet PLD Comecouss oussNo ratings yet

- Documenting and ReportingDocument3 pagesDocumenting and ReportingGLADYS GARCIANo ratings yet

- VTM 1sted 1-Page Caitiff InteractiveDocument1 pageVTM 1sted 1-Page Caitiff InteractivePanaSikuNo ratings yet

- Peronsal Construct TheoryDocument7 pagesPeronsal Construct TheoryToby PearceNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper (Group4)Document3 pagesReaction Paper (Group4)MARC MARVIN PALOMARESNo ratings yet

- FKG Catalogue 2015Document68 pagesFKG Catalogue 2015Septimiu TiplicaNo ratings yet

- Validation Master Plan ExampleDocument11 pagesValidation Master Plan ExampleAjay GangakhedkarNo ratings yet

- BSP-Medical FormDocument1 pageBSP-Medical FormNyleg Aicilag100% (2)

- L3 Hematology Regulation of Iron MetabolismDocument3 pagesL3 Hematology Regulation of Iron MetabolismMurtadha AlrubayeNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Test Battery For Different Age GroupsDocument14 pagesDiagnostic Test Battery For Different Age GroupsDhana KrishnaNo ratings yet

- 2022 Benefits Enrollment GuideDocument28 pages2022 Benefits Enrollment GuideWyattNo ratings yet

- Bottle Packing Price List 2020-21Document21 pagesBottle Packing Price List 2020-21healerharishNo ratings yet

- QA On Conformity Assessment Procedures For PPE and MD - v2.0 - 10 July 2020Document9 pagesQA On Conformity Assessment Procedures For PPE and MD - v2.0 - 10 July 2020flojanas3858No ratings yet

- Histology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Apical AbscessDocument4 pagesHistology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Apical AbscessPrince AmiryNo ratings yet

- CS Form No - 6, Revised 2020 (Application For Leave) (Fillable) - 1Document3 pagesCS Form No - 6, Revised 2020 (Application For Leave) (Fillable) - 1ben carlo ramos srNo ratings yet

- Method Statement For Installation of Telephone ManholeDocument4 pagesMethod Statement For Installation of Telephone ManholemujtiobamaliblNo ratings yet

- STAT 2300 Test 1 Review - S19Document19 pagesSTAT 2300 Test 1 Review - S19teenwolf4006No ratings yet

- Week Four AssignmentDocument4 pagesWeek Four AssignmentRachel Elaine WilliamsNo ratings yet

- ReportViewer - Aspx 3Document1 pageReportViewer - Aspx 3Mohammed SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Value Proposition-A Comparative StudyDocument13 pagesValue Proposition-A Comparative StudyMeh Gorkhali PersonNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance/Preparation and of The Company/UndertakingDocument13 pagesSafety Data Sheet: 1. Identification of The Substance/Preparation and of The Company/UndertakingDamarys PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Waste Management Problem in Raghumanda Village: Department of Civil EngineeringDocument14 pagesWaste Management Problem in Raghumanda Village: Department of Civil EngineeringHémáñth RájNo ratings yet

- Technical Requirements in Vitro Diagnostics (IVD)Document4 pagesTechnical Requirements in Vitro Diagnostics (IVD)Raydoon Sadeq100% (1)

- Kepelbagaian Budaya (Individual Assignment)Document6 pagesKepelbagaian Budaya (Individual Assignment)Yusran RosdiNo ratings yet

- National Registry Skill SheetsDocument21 pagesNational Registry Skill SheetsKemzo AbarquezNo ratings yet

- A Visit To The Doctor - EnfermeriaDocument4 pagesA Visit To The Doctor - EnfermeriaSILVIA MARIELA LLAMOCA LIMACHENo ratings yet

- Tagalog Thesis Chapter 3Document7 pagesTagalog Thesis Chapter 3fjgmmmew100% (2)

- CXR Voucher Monthly ReportDocument2 pagesCXR Voucher Monthly Reportmarvie barbosaNo ratings yet