Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conflict and Development in Northeast India - Transnational Institute

Conflict and Development in Northeast India - Transnational Institute

Uploaded by

Anshul KandariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Conflict and Development in Northeast India - Transnational Institute

Conflict and Development in Northeast India - Transnational Institute

Uploaded by

Anshul KandariCopyright:

Available Formats

Topics EN Support us

About us Events Shop

S TAT E O F P O W E R

INDIA

Conflict and development in

Northeast India

Stories from Assam

16 May 2021

Neo-capitalist development in the form of resource extraction in the North

Eastern region of India has continuously expanded through mining,

hydroelectric power plants, and militarised infrastructure, while basic

necessities remain unmet. This has created a complex field for the

contestation of identities, land sovereignty, and conflict.

Article by Binita Kakati

Share on:

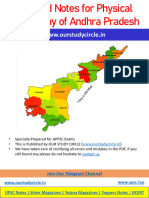

INDIA N

NORTH-EASTZONEMAP

A L

CH

A ESH

U N

A PRAD

R

-SIKKIM Itanagar

Gangtok• BHUTAN

NEPAL

Dispur• ASSAM NAGALAND

Kohima

Shillong•

BIHAR MEGHALAYA

•Implial

BANGLADESH MANIPUR

Agartala, •Aizawl MYANMAR

JHARKHAND

TRIPUR

WEST MIZORAM

BENGAL

LEGEND

ODISHA

InternationalBdy.

StateBoundary

MapnottoScale

CountryCapital

Copyright©2016www.mapsofindia.com StateCapital

India’s North Eastern Region (NER) includes the states of Assam, Arunachal,

Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Pradesh, Sikkim and Tripura.

Together, they represent a distinct geographic, cultural, political, and

administrative entity. The area, which is part of the Eastern Himalayas, is also of

geo-strategic significance as it shares 90% of its borders with four countries –

Bangladesh, Bhutan, Tibet Autonomous Region/China and Myanmar, and also

with Nepal – and is connected to India by a narrow piece of land called the

Siliguri corridor, sometimes referred to as the ‘Chicken’s neck’.

The NER has the dubious reputation for including some of Asia’s most

militarised and politically volatile societies. It also has the highest number of

indigenous peoples in India, characterised by self-determination movements

that have taken the form of armed struggle against the Indian state. The NER is

also a biodiversity hotspot, including the mighty Brahmaputra River and its

many tributaries, natural reserves of oil, coal, gas and other minerals – all of

which provide another dimension to ethnic struggles and self-determination

movements.

Seventy years after independence, the states in the NER still lack basic services,

including health and education, occasionally receiving news coverage

highlighting the human rights violations that have affected the civilian

population during the years of conflict. The Union of India is a federation of

states, but the central government dictates much of the policy in the NER, and

neo-capitalist development in the form of resource extraction has continuously

expanded through mining, hydroelectric power plants, and militarised

infrastructure, while basic necessities remain unmet. This has created a

complex field for the contestation of identities, land sovereignty, and conflict.

This essay starts with brief background to the NER and goes on to look at the

most recent interventions regarding development and resource-extractive

projects in Assam and what these mean for an area that has already suffered

years of political neglect accompanied by militarisation.

A brief history of India’s North East Region

The connection between the NER and the rest of India is relatively recent, dating

back to 1826 with the signing the Treaty of Yandaboo, when Burma ceded

Assam, Manipur, Jaintia hills, Tripura and Cachar to the British at the end of the

First Anglo-Burmese War. Even under the British, the region was mostly seen as

providing a ‘buffer zone’ from Burma and China. This perspective continued

after independence and was one reason for the major army deployment and

militarised infrastructure in the region.

The integration of NER into the rest of the country was ‘abrupt ’, with no prior

history. The states were integrated and demarcated into ad hoc units for

administrative convenience, principally economic and resource planning and

security calculations. The region’s own politics or the political aspirations of

fragmented tribes were marginalised within the larger political discourse, partly

due to their small numbers.

This situation has given rise to conflict, to which the Indian government has

responded by imposing controversial laws such as the Armed Forces Special

Powers Act 1958 (AFSPA), which allows armed personnel to conduct arrests,

searches and encounters without a warrant. The actions permitted under the

Act are not subject to the law of the land and violations cannot be pursued in the

courts. Currently, AFSPA is enforced in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur,

Meghalaya Mizoram and Nagaland, and has not been conducive to

development, peace or stability.

The insurgency and the consequent counter-insurgency measures became a

part of everyday life . The attendant human rights violations, combined with

sluggish economic growth in the region, has paralysed development, further

enabling illicit economic enterprises in an already militarised zone. The

response of the central government has included ill-considered approaches to

conflict management and the injection of development funds into the oil, tea

and coal sectors, all of which are concentrated on resource extraction. Together,

these have nurtured a climate of ‘sustained low intensity conflict’ , which

allows many activities to fly under the radar and for government officials,

political elite and armed rebels to control their respective sub-states. In

conversations in Assam, a young Mising friend said:

‘… they cut the young trees! They don’t even wait for them to grow a little. We

never cut young trees. Of course, they [the state officials] know that there is

illicit mining. They won’t be able to carry out these activities without the

knowledge of the state officials. But they only think of their benefit – now’.

This sentiment also resonated in Sikkim about how development projects affect

and change landscapes and people’s experiences. A Lepcha activist in Sikkim

explained that he has been depicted as espousing ‘anti-development’ by

opposing state-backed development projects, accused of wanting to push the

region into backwardness, to which his response is:

‘We live in hilly terrain, what does a bureaucrat making plans in Delhi know

about the geography of a region like this and how large-scale projects affect us?

The dynamite they are using to blow up the forests causes landslides every

season. The soil becomes loose. We don’t cut down trees. We cut them when we

need to use [the timber] to build our homes but for that, there is a process

through which we choose a tree, we pray to it and then we cut it. We aren’t

against development – this branding is done to make it easy to dismiss our

concerns. The Teesta is a powerful river and I understand why they want to

harness it but you cannot disrupt the flow of the river wherever you want. These

projects are funded by the World Bank and the like and are implemented with

the goals of getting carbon credits, but what do we get from it?’

A few hours later the valley rang with the sound of explosions – to make new

roads into the valley. As we sat listening to birdsong and people’s stories, the

deafening explosion felt even louder in the knowledge that nature seems to

exist only to be taken.

History of resource extraction

‘Tez dim, kintu tel nidieu’, meaning ‘We will give our blood, but we won’t give our

oil’.

These words came to signify the Assam Agitation when in 1980, Dulal Sarma, a

leader of the All Assam Students Union (AASU), slashed his chest with a blade

and drew out blood to write these words across a street in Guwahati. The words

resonated with the rebels who made opposition to resource extraction central

to the armed rebellion.

The Assam Agitation began in 1979, with a number of demands – primarily

economic development, recognition of cultural identity and illegal migration

that was causing displacement of farmland, and resource extraction. Assam has

historically had two large industries – tea and oil – with one of the country’s

oldest refineries located in Digboi. Yet a region that at the time of independence

had a stronger economy than the rest of the country, soon afterwards suffered

low GDP, poor infrastructure and lack of access to education and health care,

leading to very high rates of infant and maternal mortality. These factors

contributed to the Assam Agitation, which started as a students’ movement and

soon became an armed conflict against the Indian state. It continued for six

years and cost a total of 885 lives. The United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA)

was the main active group, along with smaller groups such as the National

Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB). While initially the armed rebel groups

enjoyed mass support, the situation soon led to a parallel economy involving

kidnappings and arms smuggling. The Indian government launched several

operations to quell the armed opposition, including Operation Rhino and

Bajrang. The last was Operation All Clear, which was conducted in collaboration

with the Bhutanese army.

By late 1990s it was considered that the armed rebellion in Assam had officially

ended, but factions continued to exist. After many members of the ULFA

surrendered (SULFA), the government mobilised to murder supposed

sympathisers. Those years were known as ‘Secret Killings of Assam’, whereby

people who were considered to sympathise with the cause were kidnapped or

shot by state-backed police or surrendered militants. Those years created a

generalised sense of fear, and many questions remain unanswered for the

families of the disappeared.

Whose land is it? Contextualising citizenship and

indigenous rights

In 2019 the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which excluded Muslims from

legal frameworks to obtain citizenship, prompted nationwide protests. However,

in Assam and Tripura where the protests started, the issue was not about the

exclusion of Muslims but rather the outright rejection to granting citizenship to

any immigrants regardless of their religion. The country was confronted with

this narrative of the NER, where Assam became the pivot through which the

CAA was conceived and later implemented. The CAA followed an arduous

process of implementing the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam. In

the final list, an estimated 1.9 million people were excluded, a disproportionate

number of whom were Hindus. The CAA was brought in by the ruling right-wing

Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) to reinstate those omitted from the register – but

only if they were Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Jains, Parsis or Sikh, not if they were

Muslim. This would effectively reinstate 90,000 of the 1.9 million and pave the

way for others to seek citizenship.

The question of citizenship and indigenous rights has a long history in the NER

with its distinct cultural, social, racial and linguistic identity that has shaped its

historical struggle to become a part of the imagination of the Union of India.

Most states, including Assam, have had a history of armed rebellion and the

assertion of indigenous identity. These movements have also shaped the fears

of indigenous populations being displaced and alienated from their land –

something that has indeed happened through development projects,

uncontrolled migration and even on the pretext of expanding conservation

areas. This struggle contributed not only to people’s stance on the CAA but also

to the invisibility of their narrative in the national discourse. Sanjib Baruah

writes ‘There is a long history of resistance to colonial and postcolonial rulers

treating their territory as land without people – or land with barely any people’.

The region and its people were considered a ‘homogenous, undifferentiated

mass’ which would better serve the Indian Union through resource extraction or

occupation.

Another reason for the longstanding Assam Agitation and armed rebellion with

the Indian state was over the questions of mass immigration from Bengal and

East Bengal. At the time of partition, the leadership in India decided that Assam

(which then included Meghalaya and Mizoram) was to go to East Pakistan since

it shares no border with India. The fear of becoming a cultural and linguistic

minority in a Muslim-majority nation prompted the Assamese people to seek to

become a part of the Indian Union. It was under the leadership of the chief

minister Gopinath Bordoloi, along with Gandhi, that this took place.

Soon after independence, immigration from the new country of Bangladesh was

inevitable, especially into Assam and Tripura with their porous border. The

backlash from Assam came in as early as 1950s but since the region was not

fully understood by New Delhi, such concerns were not addressed. In 1978

India’s Chief Election Officer spoke publicly of the ‘large-scale inclusions of

foreign nationals in the electoral rolls’ . In the by-elections held in Mangaldoi

in the same year, it came to light that there was a phenomenal rise in voters,

which was attributed to the inclusion of illegal migrants from Bangladesh in the

electoral rolls. The student bodies in Assam asked the Indira Gandhi

government to postpone the elections until an agreement was reached on

deleting foreigners from the electoral rolls. The Nellie Massacre took place on 18

February 1983 days after the Assembly elections. There had been isolated

incidents of violence and the Assam police had cited Nellie as a “troubled”

spot . The official narrative claims that Tiwa, Lalung and Assamese tribesmen

descended from the hills and over the course of a few hours massacred the

people in Nellie and a few neighbouring villages. Official numbers state a total of

2,191 lives were lost.

The victims were Muslim immigrants from Bangladesh. The survivors of the

massacre distinctly remember the villages being cordoned off for months and

for at least 24 hours before the massacre took place, and that none of their

Assamese neighbours were among those wielding daos or machetes. This begs

the question of who participated in the massacre. The Tewary Commission

Report suggested the involvement of the RSS, the youth wing of the BJP. Is it not

too far-fetched to imagine that political parties thrived on the chaos their own

policies had created. Subsequent governments have treated the region as a

field to secure their own seats in the parliament, which shows that the region

has not only functioned as a “disturbed area” but one in which the

continuation of disorder has been encouraged to benefit those in power to

retain and maintain their power. While migration from partition is a continuing

process, the lack of development in the region and the historical atrocities

experienced by local people creates the field for ethnic violence.

The Assam Agitation fed off some of these tensions and only came to an end

with the signing of the Assam Accord in 1985. It was decided that ‘foreigners

who came to Assam on or after March 25, 1971’ (the cut-off date for the rest of

the country had been set at 1951) would be detected and expelled. Its Clause 6

said: ‘Constitutional, legislative and administrative safeguards, as may be

appropriate, shall be provided to protect, preserve and promote the culture,

social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people’. The BJP came to

power on the promise of implementing the Assam Accord in ‘letter and spirit ’,

which the CAA violated.

Leading up to the CAA in 2019, fear was again mounting that the indigenous

population in the NER would lose their culture, identity and land. At present,

Assamese is the first language of 48% of the population; many feel this

foretold a future as dismal as Tripura where the indigenous population have

been reduced to 30 per cent and have lost more than 40% of their land to

migrants. It is automatically assumed that the fears arise from xenophobia,

which not the case as land has a particular significance for communities who

eke a living out of subsistence farming. The fear is not about religion or the

‘other’ but rather a tangible fear of losing their living and way of life in a context

where the state offers them no protection.

In an interview , Dr Walter Fernandes of Northeastern Social Research Centre,

describes the problem as economic, revolving around the question of land. He

emphasises that religious persecution is not the primary cause for migration

from Bangladesh but rather economic conditions and high population density,

which makes migration essential to the ‘demographic balancing process’,

noting that ‘most come and occupy what is known as common land which is two

thirds of the land in Assam. The CAA paves the way for further immigration

which will pose a threat to the land, language and culture and the whole social

system. That can mean ethnic conflict’.

The region’s historical struggle is also an extension of India’s colonial past.

Armed rebellion from the borderlands against the state existed even during

colonial times and the troubled post-colonial integration of the NER with the

rest of the country has never fit into the ‘standard narrative of democracy in

India’ combined with draconian laws such as the AFSPA. As early as 1980,

academics and activists were making the argument that the region suffered

internal colonialism. This idea was also the basis of the ideology of the ULFA.

The unfulfilled promises of the Assam Accord created the political space for the

rise of the ULFA, which started as an attempt to ‘avenge the perceived betrayal

of the Assamese people by the central government’ .

The loud protests in December 2019, after years of historic marginalisation,

have therefore hit at the only aspect the people believe they have retained –

their identity. The perception of threat is shared across the NER. Indigenous

people in the borderlands face the struggle of establishing and preserving the

integrity of their cultural identity. Most communities in the region are

subsistence farmers with no constitutional or legislative means to guarantee

ownership of their land. The CAA was viewed as paving the way for uncontrolled

inroads into their lands through demographic changes which would also affect

their political rights.

Development and extraction

‘This development feels like an invasion!’ – Mamang Dai

Apart from the CAA, government decisions to expand resource extraction in the

region have also involved increasing securitisation. Most of these projects

threaten to damage sensitive ecological and biodiversity zones. Kikon writes

about how the nineteenth-century discovery of oil and coal in the region and

resource politics have shaped people’s lives, with militarisation and violence

becoming part of the construction of the region and of people’s lives.

Development and the exploration of resources go hand in hand ideologically,

creating ‘enclaves’ of health, prosperity and safety facilitated by the resource-

extraction industries. These zones are also militarised, but to protect them from

the outside – the people for whom the project was intended.

In January 2020, the Government of India released notification of the draft law

for Environment Impact Assessment 2020, which gave rise to public concerns

about various provisions that would allow industries to avoid environmental

accountability. The draft notification allowed industries that have violated

environmental laws to continue operating by paying a penalty after the event.

The new notification also inverted the ‘precautionary principle’ , which was

previously fundamental to India’s environmental approach and allowed for an

initial assessment of the environmental impact of projects. The notification

made provisions for industries to be exempted from public hearing clearance or

consultation with the people affected, or with state-level bodies. This is of

importance in the NER, as many indigenous tribes live in protected areas and

would possibly be displaced by development projects. For example, in the

public hearing on the Dibang dam, 99% of the speakers from tribal communities

who live in the area proposed for the dam opposed the project. The Dibang

Valley projects are also estimated to submerge 4,577.84 hectares of

biodiversity-rich forest area and have an impact on areas downstream,

including the Dibru-Saikhowa National Park in Assam. Since 2007, there have

been protests by the Students Union and Akhil Gogoi, an activist who has been

imprisoned since December 2019 by the National Investigative Agency under

the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) – another piece of legislation that

has been widely used to incarcerate activists and dissenters.

In May 2020, a gas well operated by a government-owned subsidiary company

– Oil India Ltd. – had a blowout in Baghjan, Assam. Two weeks later the blowout

became a blaze that engulfed the region as the oil well was located between a

wetland and a national park. The leakages caused irreparable ecological

damage. Official documents later showed that the company expanded

operations into the ecologically sensitive zone without the public hearings

mandated by the environmental law in force at that time.

In the same month, the Assam Forest Department issued a fine for Rs. 43.25

crore to Coal India (the subsidiary of a state-owned company) for having carried

out illegal mining in a reserved forest for 16 years. Soon after, The National

Board for Wildlife granted approval to Northeastern Coalfields (NECF), part of

Coal India, for coal mining in Dehing-Patkai forest reserve, thus legitimising

mining deemed illegal by the High Court. Soon after, the Twitter campaign

#SaveAmazonOfEast from the ‘coal mafia’ began. In July, the Assam state

government passed an ordinance to curtail land-use norms in order to

facilitate rapid industrialisation. The Union Ministry for Environment, Forest and

Climate Change (MoEFCC) gave clearance for the extension of drilling and

testing of hydrocarbons at seven locations by OIL under the Dibru-Saikhowa

National Park area. The area also includes the Maguri-Motapong wetland area.

In July 2020, the government announced an ordinance that would allow the

conversion of land for micro, small and medium enterprises to set up industries

without the need for any license or clearance, raising fears about the

expropriation of indigenous people’s land. Since 2015, Patanjali, one of the

largest businesses in India with annual sales of $1.6 billion in 2018, has acquired

approximately 1485.6 hectares of land to open up industries, flying in the teeth

of popular protests. In an interview, one of the factory managers revealed that

large tracts of forests had been cleared in elephant ‘corridors’ displacing herds

of wild elephants. Based on interviews conducted as part of my fieldwork in

December 2019, the company has also formed an illicit economy in

collaboration with government officials for tracking and procuring protected

species of plants from reserved forests and conservation sites. This kind of

network is also seen in areas where illegal mining is rampant , often in

collaboration with state officials and the political elite.

These events put into perspective the different ways in which development is

manipulated in resource-rich frontier regions to serve extractive industries or in

collaboration with local elite to form illicit economies. Both scenarios function

outside legal frameworks or create increasing militarisation to change them.

Academics in the region such as Sanjib Baruah have shown how some social

sectors were beginning to see the reality of the ‘slow violence’ of health risks

associated with air and water pollution that extraction projects inflicted on local

communities.

In conversation with the members of the Mising community, regarding an agro-

forestry project in the region focused on livelihood generation and spearheaded

by a non-government organisation (NGO), they expressed their fear of being

displaced once the planting of trees starts. Over time many communities living

on the edge of a forest have faced displacement when the government has

decided to expand into ‘protected areas’; in most cases these areas become the

sites of illicit mining, poaching, and timber logging, with the knowledge of forest

officials and often in collaboration with them. Categories of ‘protected areas’

and the legal provisions governing them have over the years been used to

displace communities from their land. Kikon writes that he imposition of laws

such as the AFSPA and use of the terms such as ‘disturbed area’ and ‘suspicion’

have created an environment of mistrust and intimidation – there is one armed

personnel for every ten people living in the NER.

In the sort of intervention seen in the NER, the state is seen as the guardian of

the assets of the region. Mcduie-ra, writes about how insurgency or the armed

rebellion in the region is seen as being connected to the lack of development,

with the World Bank declaring that poverty and lack of development are among

the factors contributing to the instability – the prevailing assumptions being

that ‘the northeast is poor because of the conflict or there is conflict because

the northeast is poor’.

Further, in writing about Manipur state, he mentions that words such as

‘development’ or ‘infrastructure’ acquire a new meaning in the region. In Assam,

they are used interchangeably, having the same meaning in Assamese as the

word ‘unnati’ meaning progress. The conflation of the categories of economic

and social ‘advance’ have been used as the underlying discourse to justify

extractivist infrastructure in the region, which is mostly securitised and

concentrated on connecting roads and highways. This is also evident in the

numerous banners and signs in Assam put up by coal and oil companies, and

referring to progress in the region.

Scholars from the region such as Dolly Kikon, have referred to it as a ‘militarised

carbon landscape’ with a history of securitised infrastructure and resource

extraction functioning within the trope of development. She asks, ‘How do we

still manage to conveniently walk away from seeing the interconnection of

extractive violence, consumption, market, extractive regime, and labour around

us? ’

Lived experience

‘Ami Ugrapanti Nohoi’ – ‘We are not militants’

These were among the first words spoken and often repeated during my

interviews conducted in a Bodo village in Assam in January 2020, with frequent

references to the ‘boys’ of the armed rebels – the aim being to reassure me that

the villagers did not harbour them. In fact, the armed rebels ensure that the

‘boys’ who join from a certain village don’t go back there to seek shelter lest it

put their family at risk, or that their family insists that they become state

informants. These words are also reminiscent of the times of the Secret Killings

of Assam. There are many things that people do not wish to remember or bring

up now . This was also evident in many of the interviews I conducted with

politicians, who constantly reiterated that the past must be forgotten.

Incidentally these are the same politicians and bureaucrats who are implicated

in illicit activities and extra-judicial killings. They constantly say ‘it was in the

past, let us move on’, while families still don’t know where the remains of their

loved-ones are buried.

While speaking to one of the villagers, a young man who is also a member of the

village council reluctantly spoke about the illicit sand mining in the area.

‘In the absence of job opportunities what are people supposed to do? They work

as daily wage labourers in the sand mines and illegal timber trade. They know

they get paid very little. They know the owners – which includes some people

from the tribe but not from the village, the government officials including forest

officials and the business contractors are all earning a lot from illegal trade.’

In the case of Assam, multiple layers of authorisation have been enacted with

the sole aim of resource extraction, and militarisation facilitates the extractive

network. This illustrates the complex linkages between nature, the nation and

the nationalities that make up these spaces – relationships that lie at the heart

of unlocking the perpetual ‘environmental crisis’ that the region seems to be

going through.

This essay has shown how development operates on the ground in Assam, in

conjunction with many other factors. Government thinking has been that

development would allay the region’s grievances, which have themselves arisen

by ignoring regions that have been or are still affected by conflict. First,

inequitable economic growth is unable to erase the historical injustices in the

region. In the case of the Assam the structures of power between oil companies,

local stakeholders and the central government intersect to create a structural

framework of extraction. Development in the NER has always been securitised

in an area already highly militarised. The continuation of this dynamic in an

increasingly politically volatile region has given rise to the fear of history

repeating itself. In the last year indigenous communities have taken a stand,

making it imperative to acknowledge alternative histories and stories of

development in which indigenous communities and their claims to their land are

not dismissed as ‘terrorism’ and ‘parochial’. It is evident that the problems in the

North East Region are not exclusive to the region but resonate with other parts

of the Global South, which can be solved only when communities are heard and

acknowledged.

Correction Sept 7, 2021: An earlier version of this story missed attribution of

Dolly Kikon's quote ‘How do we still manage to conveniently walk away from

seeing the interconnection of extractive violence, consumption, market,

extractive regime, and labour around us? ’ to its source The Bastion

S TAT E O F P O W E R

INDIA

CREDITS Binita Kakati

Share on:

Do you want to stay informed?

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to our

Sign up for the newsletter to receive monthly updates on TNI’s

research, events, and publications.

newsletter

SUBSCRIBE NOW

MORE LIKE THIS

S TAT E O F P O W E R

Coercive World

State of Power 2021

Report

16 May 2021

About us Vacancies

Events Finances Transnational Institute Call us

De Wittenstraat 25 +31 20 662 66 08

Annual reports TNI Shop 1052 AK Amsterdam Email

The Netherlands tni@tni.org

Associates Support us

Our team

Twitter Facebook Instagram Youtube

Creative Commons License Corrections and Complaints Privacy Policy ANBI

You might also like

- Multiple Choice Questions Subject: Accountancy Class: XiDocument4 pagesMultiple Choice Questions Subject: Accountancy Class: XiShahid NaikNo ratings yet

- The British and French Mandates in Comparative Perspectives Les Mandats Francais Et Anglais Dans Une Perspective (Social, Economic and Political Studies of The Middle EDocument769 pagesThe British and French Mandates in Comparative Perspectives Les Mandats Francais Et Anglais Dans Une Perspective (Social, Economic and Political Studies of The Middle Eheghes100% (1)

- English File - Upper-Intermediate - Student's Book With ITutor (PDFDrive) (Trascinato)Document1 pageEnglish File - Upper-Intermediate - Student's Book With ITutor (PDFDrive) (Trascinato)Camila Sanhueza SidgmannNo ratings yet

- Group-02 SST Art Integrated Project-1Document18 pagesGroup-02 SST Art Integrated Project-1Ankur Yadav67% (3)

- North East IndiaDocument10 pagesNorth East IndiascNo ratings yet

- Research 2Document10 pagesResearch 2Sreejayaa RajguruNo ratings yet

- AKSHATA KASHYAP PPT ManipurDocument20 pagesAKSHATA KASHYAP PPT ManipurAkshata Kashyap80% (5)

- 3 Manipur - Folk SongDocument25 pages3 Manipur - Folk Songbikramjit48100% (1)

- Insurgency in NE PDFDocument27 pagesInsurgency in NE PDFMohammed Yunus100% (1)

- State GazetteerDocument505 pagesState GazetteerSudhip DeyNo ratings yet

- Northeast InsergencyDocument4 pagesNortheast InsergencyAyush RajNo ratings yet

- Man&society2010 7Document153 pagesMan&society2010 7RipunjoyNo ratings yet

- North Eastern Council Regional PlanDocument27 pagesNorth Eastern Council Regional PlanSmriti SNo ratings yet

- Social Science Portfollio: Salivan Singh Shaktawat Class 9 ADocument19 pagesSocial Science Portfollio: Salivan Singh Shaktawat Class 9 AArundhati ShaktawatNo ratings yet

- 86-Article Text-309-1-10-20210519Document16 pages86-Article Text-309-1-10-20210519Siti Fatimah NiatNo ratings yet

- Abstract July-Sep 2016Document14 pagesAbstract July-Sep 2016Madhu GNo ratings yet

- 2024 01 02current - PDFDocument17 pages2024 01 02current - PDFhyreinsanNo ratings yet

- Applicability and Relevance of Inner Line Permit (Ilp) in Arunachal Pradesh.Document3 pagesApplicability and Relevance of Inner Line Permit (Ilp) in Arunachal Pradesh.IOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Uttar Par DeshDocument22 pagesUttar Par DeshHansel GoyalNo ratings yet

- North EastDocument8 pagesNorth EastMD YUSUFNo ratings yet

- The North East Chronicle (Volume 1, Issue 2)Document42 pagesThe North East Chronicle (Volume 1, Issue 2)santhoshraja vNo ratings yet

- Economic Challenges and Opportunities For North Eastern Region of IndiaDocument22 pagesEconomic Challenges and Opportunities For North Eastern Region of IndiaRishabh Sen GuptaNo ratings yet

- Sharon Takim Anambra State Assessment For KIFDocument41 pagesSharon Takim Anambra State Assessment For KIFSharon TakimNo ratings yet

- Haza DFR - MakDocument203 pagesHaza DFR - MakHayat Ali ShawNo ratings yet

- Chapter-2: Pe Fe. F Ha A:: RegionDocument29 pagesChapter-2: Pe Fe. F Ha A:: RegionMANOJNo ratings yet

- Social ProjectDocument37 pagesSocial ProjectShubh agrawalNo ratings yet

- Development of North East RegionDocument5 pagesDevelopment of North East RegionD M KNo ratings yet

- Geography Class 9Document9 pagesGeography Class 9golu150188No ratings yet

- From Chai To Thai - A Journey Into The North East IndiaDocument6 pagesFrom Chai To Thai - A Journey Into The North East Indiaananya.swarnkar23No ratings yet

- Physical Geography of Andhra PradeshDocument33 pagesPhysical Geography of Andhra Pradeshfitnesshunt.777No ratings yet

- States of India (Gnv64)Document100 pagesStates of India (Gnv64)Sujeet Mishra100% (1)

- Insurgent Frontiers: Essays From The Troubled NortheastDocument25 pagesInsurgent Frontiers: Essays From The Troubled NortheastpraveenvatsyaNo ratings yet

- Military LawDocument29 pagesMilitary Lawgauravtiwari87No ratings yet

- North East IndiaDocument14 pagesNorth East Indiaeg class100% (1)

- Security UnacademyDocument110 pagesSecurity UnacademyAlex starrNo ratings yet

- Geography, Land, Boundaries and NeighborhoodsDocument3 pagesGeography, Land, Boundaries and NeighborhoodsasasasNo ratings yet

- TCW Week 8Document25 pagesTCW Week 8Ylla ShedNo ratings yet

- NagDocument2 pagesNagmsatija2007No ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 3Document24 pages11 Chapter 3RD ZaiaNo ratings yet

- APState Profile2014-15Document113 pagesAPState Profile2014-15VenuGopalNagamNo ratings yet

- Papum Pare DistrictDocument199 pagesPapum Pare DistrictsajinbrajNo ratings yet

- Physical Features of India 1Document22 pagesPhysical Features of India 1Shreya PandeyNo ratings yet

- 2017 Introducctionto South Asia Power PointDocument33 pages2017 Introducctionto South Asia Power PointsidraNo ratings yet

- NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH UpdatedDocument57 pagesNEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH UpdatedSanju ChandNo ratings yet

- Jaipur Cit Y: Names - Aayushi Chhajer, Aman Jain, Amit Kumar Singh - Archit TyagiDocument4 pagesJaipur Cit Y: Names - Aayushi Chhajer, Aman Jain, Amit Kumar Singh - Archit TyagiArchit TyagiNo ratings yet

- Geographical Outline of BangladeshDocument8 pagesGeographical Outline of BangladeshMahbubNo ratings yet

- Facies Analysis and Reservoir Characterization of Mesozoic-Cenozoic Sediments From Drilled Well Section at Bankia Structure, Jaisalmer BasinDocument14 pagesFacies Analysis and Reservoir Characterization of Mesozoic-Cenozoic Sediments From Drilled Well Section at Bankia Structure, Jaisalmer BasinSaeed AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Incurgency in AssamDocument9 pagesIncurgency in AssamaniketakshayNo ratings yet

- B Asdasd AsdDocument2 pagesB Asdasd Asdkkaafow5xrNo ratings yet

- Statistical Modeling of Rainfall Data in Sangli DistrictDocument89 pagesStatistical Modeling of Rainfall Data in Sangli Districtapi-257948335No ratings yet

- Polity - Reorganization of States and Dynasties - English - 1604946037Document9 pagesPolity - Reorganization of States and Dynasties - English - 1604946037Anuj Singh GautamNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Tourism For Regional Development in North-East States of India - Trends, Problems and ProspectsDocument15 pagesSustainable Tourism For Regional Development in North-East States of India - Trends, Problems and ProspectsAtiqur Rahman BarbhuiyaNo ratings yet

- Physical Features of IndiaDocument69 pagesPhysical Features of IndiaMohit Saraswat100% (1)

- Indian Geography Revision SlidesDocument256 pagesIndian Geography Revision SlidesSateesh100% (1)

- India - The Size and LocationDocument12 pagesIndia - The Size and LocationVisak jish Cartoon comediesNo ratings yet

- Asian RegionalismDocument18 pagesAsian RegionalismKielvin MosquitoNo ratings yet

- 09 Chapter 2Document27 pages09 Chapter 2priyanka sehgalNo ratings yet

- Chapter-Ii Telangana Peasant Insurrection: A Historical StudyDocument37 pagesChapter-Ii Telangana Peasant Insurrection: A Historical Studyhari sharmaNo ratings yet

- South Asia Geography, Countries, History, & Facts BritannicaDocument1 pageSouth Asia Geography, Countries, History, & Facts BritannicasnowNo ratings yet

- Nagaland State InformationDocument4 pagesNagaland State InformationCHAITANYA SIVANo ratings yet

- Meghalaya and Arunachal PradeshDocument7 pagesMeghalaya and Arunachal PradeshMohd HumairNo ratings yet

- Notes About StateDocument21 pagesNotes About Stateabhijit488No ratings yet

- 637026943259224445MEGACLUSTERNEWDocument42 pages637026943259224445MEGACLUSTERNEWMeenatchiNo ratings yet

- Use The ForceDocument3 pagesUse The Forcehelpdesk5562No ratings yet

- Camille Realty Journal To FSDocument9 pagesCamille Realty Journal To FSVenus AriateNo ratings yet

- Undergraduate Programmes Offered: NotesDocument1 pageUndergraduate Programmes Offered: NotesWazaNo ratings yet

- 11 Tips To A Better Sun SalutationDocument3 pages11 Tips To A Better Sun SalutationHazel100% (1)

- Hadoop/Hbase Installation: Install JavaDocument11 pagesHadoop/Hbase Installation: Install Javashiva_1912-1No ratings yet

- Modulo 5Document36 pagesModulo 5HUNTER Y TANKNo ratings yet

- TT09Document8 pagesTT0922002837No ratings yet

- Lectures On Biostatistics-ocr4.PDF 123Document100 pagesLectures On Biostatistics-ocr4.PDF 123DrAmit VermaNo ratings yet

- Green Methanol Production Process From Indirect CO2Document57 pagesGreen Methanol Production Process From Indirect CO2Melinda FischerNo ratings yet

- Theory 1Document62 pagesTheory 1Suraj SubediNo ratings yet

- Mariano Marcos State University: College of Teacher Education Laoag City, Ilocos NorteDocument8 pagesMariano Marcos State University: College of Teacher Education Laoag City, Ilocos NorteEisle Keith Rivera TapiaNo ratings yet

- Eoffice - PresentationDocument26 pagesEoffice - Presentationron19cNo ratings yet

- Hardness Conversion TableDocument3 pagesHardness Conversion TableNisarg PandyaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Dense Stereo Matching Metrics For Real Time ApplicationsDocument3 pagesComparison of Dense Stereo Matching Metrics For Real Time Applicationssendtomerlin4uNo ratings yet

- 4 11h French Lesson 6 Study MaterialDocument76 pages4 11h French Lesson 6 Study MaterialBublieNo ratings yet

- Investment Key TermsDocument32 pagesInvestment Key TermsAnikaNo ratings yet

- DV Appendix 32-DECEMBER 2019 JHSDocument7 pagesDV Appendix 32-DECEMBER 2019 JHSRomel BayabanNo ratings yet

- Explanation': Certlflcatelnco-Operativehousingmanagement: ToDocument4 pagesExplanation': Certlflcatelnco-Operativehousingmanagement: ToShahnawaz ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Shantanu Lamichhane-Signed PatioDocument15 pagesShantanu Lamichhane-Signed PatioShantanu LamichhaneNo ratings yet

- The Making of Filipino EntrepreneurDocument11 pagesThe Making of Filipino Entrepreneurjulia_jayronwaldo100% (1)

- 2nd SemesterDocument2 pages2nd SemesteralokNo ratings yet

- IBM - Mail File Is Slow To ..Document3 pagesIBM - Mail File Is Slow To ..Saravana Kumar100% (1)

- Itu-T: Gigabit-Capable Passive Optical Networks (GPON) : General CharacteristicsDocument25 pagesItu-T: Gigabit-Capable Passive Optical Networks (GPON) : General CharacteristicsDeyber GómezNo ratings yet

- Domestic Consolidated Lounge List 1st June 2023Document11 pagesDomestic Consolidated Lounge List 1st June 2023Prateek PanjwaniNo ratings yet

- Refractory Precast FerrulesDocument2 pagesRefractory Precast FerruleschoksNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Specifications 1. Major Component: 130ZF2SP01Document22 pagesGroup 2 Specifications 1. Major Component: 130ZF2SP01المهندسوليدالطويلNo ratings yet