Professional Documents

Culture Documents

15B.Lerner On The Economics of Control

Uploaded by

Prieto PabloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

15B.Lerner On The Economics of Control

Uploaded by

Prieto PabloCopyright:

Available Formats

Lerner on the Economics of Control

Author(s): Milton Friedman

Source: Journal of Political Economy , Oct., 1947, Vol. 55, No. 5 (Oct., 1947), pp. 405-416

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1825534

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1825534?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Journal of Political Economy

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE JOURNAL OF

POLITICAL ECONOMY

Volume LV OCTOBER 1947 Number 5

LERNER ON THE ECONOMICS OF CONTROL

MILTON FRIEDMAN

T HE recent book by A. P. Lerner, ments seem to be derived from the for-

The Economics of Control, is an mal analysis and supported by it,

analysis of the problem of maxi- though, in fact, the formal analysis is a

mizing economic welfare.' It deals with most entirely irrelevant to the institu-

a wide range of the substantive topics tional problem.

requiring attention: the organization of The result is that not only the title

production and allocation of resources and the introduction but even a first

under given conditions; the distribution reading somehow generate the expecta-

of income; the role of investment and the tion and the illusion that the book con-

adaptation of society to investment; un- tains a concrete program for economic

employment and the business cycle; and reform. "In this way we shall be able to

foreign trade. On each topic it seeks to concentrate on what would be the best

derive the formal conditions for an thing that the government can do in the

optimum and to propose institutional ar- social interest-what institutions would

rangements adapted to achieving these most effectively induce the individual

conditions. members of society, while seeking to ac-

Most of the book is devoted to the complish their own ends, to act in the

formal analysis of the conditions for an way which is most beneficial for society

optimum. The institutional problems are as a whole" (p. 6). An attempt to set

largely neglected and, where introduced, down the explicit details of the program

treated by assertion rather than analysis. dispels the illusion. Much of what at

This disparity in the attention devoted first reading sounds like a concrete pro-

to the formal and institutional problems posal, particularly about the general

is, however, obscured by an intermin- structure of society, turns out to be

gling of the formal and institutional simply an admonition to the state that

analysis. Formal analysis takes on the it behave correctly and intelligently.

The hortatory character of the pro-

cast of institutional proposals, and con-

posals is foreshadowed in Lerner's initial

clusions about institutional arrange-

discussion of "the rationally organized

I Abba P. Lerner, The Economics of Control. Nev democratic state," which he names "the

York: Macmillan Co., I944. Pp. xxii+428. controlled economy":

405

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

406 MILTON FRIEDMAN

The fundamental point of the controlled problems raised by "unpaid costs" and

economy is that it denies both collectivism and

"inappropriable services"). These special

private enterprise as principles for the organ-

problems aside, the major and well-

ization of society, but recognizes both of them

as perfectly legitimate means. Its fundamental known result is that, given the distribu-

principle of organization is that in any particu- tion of the available resources among

lar instance the means that serves society best individuals, an optimum exists when any

should be the one that prevails [p. 5].

small change in the application of re-

sources leads to a combination of decre-

Now surely it is no principle of organiza-

ments and increments in the output of

tion that society do what is best for

various goods such that there is no sys-

society. At most, it is an objective of

tem of barter exchanges whereby indi-

society, though even as an objective it

viduals would voluntarily accept the

is obviously question-begging.

increments as compensation for the

To illustrate more fully the difference

decrements.

between Lerner's formal analysis and

Much of The Economics of Control is

his institutional proposals, we turn to his

devoted to presenting the formal reason-

discussion of some of the major problems

ing underlying this broad result and to

facing the "controlled economy." Three

developing in detail its implications for

such problems occupy a central place in

various sectors of the economy-the al-

Lerner's analysis: (I) the optimum or-

location of goods among consumers, the

ganization of resources under given con-

allocation of resources among industries,

ditions, (2) the optimum division of in-

the utilization of resources within indus-

come, and (3) the dynamic problem of

unemployment and fluctuations in eco-

tries, foreign trade, and so on. Early in

nomic activity.

the analysis Lerner demonstrates the

advantage of using a monetary system in

I. THE ORGANIZATION OF RESOURCES

place of barter, and thereafter the discus-

UNDER GIVEN CONDITIONS

sion is in money terms rather than in the

physical terms in which the basic result

A. THE FORMAL CONDITIONS FOR AN OPTIMUM

is stated above. This enables him to give

Practically all economists, Lerner in- a fairly thorough exposition of current

cluded, who have worked on the static price theory along with his analysis of the

problem of the organization of resources optimum utilization of resources.

and who have regarded the welfare of This part of the book is novel in

the individual (rather than that of the exposition, though not in substance.

"state" or some special class of indi- Motivated by the question how society

viduals) as dominant and his ends as su- ought to work rather than how it does

preme have started with much the same work, Lerner puts primary emphasis on

assumptions and therefore reached much the human wants and technical possibili-

the same conclusions about the appro- ties to which society must adjust rather

priate utilization with given techniques than on the market expression of these

of given resources for given ends. Certain wants and possibilities. The result is a

special problems have received rather highly unusual organization of topics.

more attention from some than from For example, demand and supply curves

others (e.g., Lerner is especially attracted are first introduced on page I 5 I and then

by problems associated with "indivisi- only in a footnote explaining that the

bilities" and neglects almost entirely elasticities of demand and supply are

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LERNER ON THE ECONOMICS OF CONTROL 407

concepts analogous to the elasticity of free-enterprise exchange economy char-

substitution. acterized by private ownership of the

The exposition is novel not only in means of production. In such an econ-

organization but also in style. Most of it omy, prices perform five related but dis-

is entirely abstract, yet Lerner uses tinguishable functions: (I) they are a

graphs sparingly and mathematics not means of transmitting information about

at all. He uses words, abbreviated sub- changes in the relative importance of dif-

stitutes for words, and simple arith- ferent end-products and factors of pro-

metical examples. The resulting exposi- duction; (2) they provide an incentive

tion seems to the reviewer to have most to enterprises (a) to produce those prod-

of the disadvantages of a strictly mathe- ucts valued most highly by the market

matical exposition-it is abstract and and (b) to use methods of production

artificial and requires sustained attention that economize relatively scarce factors

and retention of symbols-and none of of production; (3) they provide an in-

the advantages-it is neither brief nor centive to owners of resources to direct

rigorous.2 them into the most highly remunerated

uses. Prices are enabled to perform func-

B. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS TO

ACHIEVE AN OPTIMUM tions (2) and (3) because they are also

used (4) to distribute output among the

Granted that the optimum allocation

owners of resources. And, finally, prices

of resources requires that marginal social

serve (5) to ration fixed supplies of goods

benefit equal marginal social cost, to use

among consumers.3

Lerner's terms, what institutional ar-

rangements will lead to the closest pos- Lerner places major emphasis on the

sible satisfaction of this condition?

first function. He recognizes clearly, and

Lerner's answer to this question is im- states effectively, the enormous difficulty

bedded in his analysis of the meaning and that would be involved in any attempt to

implications of the formal conditions, control directly the allocation of re-

and some measure of exegesis is therefore sources.

required to extract it. In a collectivist economy this [the allocation

The one common principle of eco- of resources] might be attempted directly by the

nomic organization underlying his an- Ministry of Economic Planning, and many

writers have proposed that it be done this way,

swer seems to be the use of the price

even claiming that such centralization would

mechanism for organizing economic ac-

be very efficient in planning everything to fit into

tivity. Lerner's acceptance of the price everything else. This would require a central-

mechanism does not, however, mean ac- ized knowledge of what is going on in every fac-

ceptance of the particular institutional tory, what are the changes from day to day in

the demands and supplies at all possible prices

arrangements with which the price sys-

of all goods and services and factors of produc-

tem is historically associated, namely, a tion at all places in the economy, as well as the

2 Lerner's discussion on pp. 8i-82 of the relation latest changes in technical knowledge in all

between marginal and average measurements is a branches of production. Obviously this calls for

simple illustration of what is meant by the state- the Universal Mind of LaPlace, as Trotsky has

ment that his exposition is not rigorous. He gives a

numerical example, states "irrespective of the figures

suggested, and this is not practical ... . Again

in any particular example we can see," and then

the solution is to call in the price mechanism

indicates the general relationship. He does, of [p. I 9].

course, state the relationship correctly; but the in-

tuitive leap from example to general result is an un-3 See F. H. Knight, Thie Economic Organization

satisfactory substitute for rigorous derivation. (University of Chicago, I33), pp. 6-I3, 31-35.

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

408 MILTON FRIEDMAN

Lerner recognizes, of course, both the guine about the ability of the Board of

interdependence of the various functions Counterspeculation to estimate what

of the price mechanism and the ef- the competitive price would be. Counter-

ficiency and desirability of the price speculation will not, however, work if the

mechanism in providing incentives to monopoly arises from indivisibilities suf-

individuals to adjust to the information ficient to lead to declining costs through-

transmitted by the price mechanism. "In out the relevant range of output, since a

private enterprise under conditions of price equal to marginal cost would mean

perfect competition .... the incentive that firms would go bankrupt. For such

is of exactly the right intensity" (p. 84). monopolies, Lerner would use govern-

The reason he rejects exclusive reliance ment ownership and operation. Lerner

on price incentives is that individuals, in would also include in the collectivist sec-

seeking to maximize their own incomes, tor some industries for which he regards

will make the adjustments that are counterspeculation as feasible, though he

socially desirable (i.e., will bring about nowhere specifies the principles on the

the satisfaction of the formal conditions basis of which he would choose between

for an optimum discussed above) only counterspeculation and government

if they have no appreciable influence on ownership when both are feasible. Simi-

the prices they pay or receive, i.e., are larly, he nowhere discusses how to dis-

operating under competitive conditions. tinguish in practice between those indus-

The presence of monopoly power means tries that are sufficiently competitive to

that private and social interests diverge. be left alone and those that are not.

Lerner would therefore use the pri- For the collectivist sector, it is obvi-

vate-enterprise exchange system only for ously necessary to provide a substitute

the competitive sector of the economy. for the price (i.e., profit) incentives

For another sector, he would use a de- operative in the private sector. Two

vice he entitles "counterspeculation" things are required: (i) instructions to

to eliminate any influence of sellers or managers how to use the information

buyers on price. By "counterspeculation," transmitted by prices; (2) means of as-

Lerner means a government guaranty suring that the instructions are followed.

to purchase an unlimited amount at a Lerner would instruct the managers to

fixed price from sellers who would other- pretend that they are operating under

wise be monopolists or to sell an un- conditions of perfect competition and to

limited amount at a fixed price to buyers play at private enterprise. His instruc-

who would otherwise be monopsonists. tions would take the form of the Rule:

The effect would be to replace a sloping

If the value of the marginal (physical) product

segment of the demand curve for the of any factor is greater than the price of the factor,

monopolist's product (or of the supply increase output. If it is less, decrease output. If it

curve facing the monopsonist) by a hori- is equal to the price of the factor continue pro-

zontal segment. If the price guaranteed ducing at the same rate. (For then the right output

has been reached.) [P. 64.]

by the government were equal to the

competitive price, it could sell what it

4 To be effective, the government would not only

purchased (or buy what it sold) in the have to guarantee to purchase an unlimited amount

open market without loss.4 Despite such from putative monopolists at a specified price, but it

comments as that cited above about the would also have to make its price the price ceiling for

private sales; and, similarly, it would have to make

difficulties of centralized organization of its price the price floor on private purchases by

economic activity, Lerner is quite san- monopsonists.

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LERNER ON THE ECONOMICS OF CONTROL 409

This sounds simple enough. The sim- regards private profits as an inadequate

plicity is, however, deceptive. The rule test of social performance.

is a purely formal statement that con-

II. THE DIVISION OF INCOME

ceals all the difficulties. Casual observa-

tion of the divergent fate of entrepre- A. FORMAL CONDITIONS

neurs in a highly competitive industry The distribution of resources among

(like agriculture, retail trade, or manu- individuals, which is taken as one of the

facturing of furniture or clothing) is given conditions in analyzing the organ-

enough to indicate the difficulty of the ization of resources, cannot, of course, be

problem, since they are trying to follow taken as given in fact, since the distribu-

the rule and have an incentive "of exact- tion can be modified by appropriate col-

ly the right intensity" to do so. lective action.

It is therefore important not only to Lerner does not consider directly the

formulate instructions but also to specify distribution of resources among indi-

effective means of assuring that they are viduals, but rather the associated prob-

followed. Lerner hardly discusses this lem of the distribution of income. The

problem at all. About all he says is that brief chapter dealing with this problem is

some incentives in the form of rewards (and extremely interesting. It presents a for-

punishment too perhaps) will have to be de- mal analysis leading to the conclusion

veloped for the manager who is subjected to the that "if it is desired to maximize the total

Rule, and there will be a delicate problem of satisfaction in a society, the rational pro-

making them neither too weak nor too strong.

cedure is to divide income on an equali-

.... It may seem strange to some that incen-

tives to efficiency could be too strong, but this

tarian basis" (p. 32). The analysis as

can be very serious. It can lead to a tyrannous given is not rigorous, primarily because

disregard for the welfare of the workers and anof appeal to "equal ignorance." It re-

inhuman red-tapism that would ultimately quires only a slight modification of the

mean less and not more efficiency [p. 84].

argument, however, to eliminate this

But this is only part, and probably the appeal and to make Lerner's conclusion

least difficult part, of the problem, as the a rigorous implication of his assump-

example of competitive entrepreneurs tions, of which the following five are es-

indicates. The manager's intentions must sential: (i) "It is not meaningless to say

not only be good; he must be able to that a satisfaction one individual gets is

translate his intentions into practice. The greater or less than a satisfaction enjoyed

higher administrators (who themselves 5 E.g.: "The possibility of an increase in gain off-

sets the possibility of the diminution of gain since

need both incentives and tests of per- they are equally likely to occur in any particular case.

formance) must have some means of de- There remains the net gain that is seen by itself in

termining the extent to which the man- the case of equal capacities but which becomes only

a probable gain on account of the possible increase or

ager has been successful in his attempt to diminution of the gain which arises with unequal

follow the rule. Under private enterprise, capacities" (pp. 29-30). (First italics mine.) "Such

profits are not only an incentive but also a blind shift from an equal division of income is just

as likely, then, to increase as to diminish total satis-

a criterion of performance and determine faction .. This would leave us indifferent as to

the entrepreneur's ability to get com- the distribution of income .... but for one other

thing that tips the scale. Although the probability

mand over resources. They cannot serve

of a loss is equal to the probability of a gain, every

these other functions in the collectivist time a movement is made away from an equalitarian

sector, since Lerner seeks to collectivize division the probable size of the loss is greater than

the probable size of the gain" (pp. 3I-32). (All italics

precisely those industries for which he mine except size.)

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4IO MILTON FRIEDMAN

by somebody else" (p. 25). This is taken Lerner recognizes, of course, that the

to mean that numerical utilities can be fifth assumption is invalid and therefore

assigned to the satisfactions enjoyed by concludes that "the principle of equality

individuals; and the values assigned to would have to compromise with the prin-

different individuals can appropriately ciple of providing such incentives as

be added. (2) "Each individual's satis- would increase the total of income avail-

faction is derived only from his own in- able to be divided" (p. 36). The difficulty

come and not from the income of others" here is that the distribution of income is

(p. 36). This means that the utility to an itself in considerable measure a resultant

individual of any given income is not a of the process of satisfying the mathe-

function of the income of other indi- matical conditions for an optimum utili-

viduals. (3) When incomes are unequal, zation of given resources. Analytically,

the amount of income an individual re- therefore, the distribution of income is

ceives is statistically independent of his not an independent "given" that can be

capacity for enjoying it, i.e., if indi- manipulated without affecting the rest of

viduals were classified by capacity to en- the analysis. This difficulty could have

joy income, the probability distribution been largely avoided by considering in-

of income would be the same for all such stead the distribution of resources. This

classes. (4) The marginal utility of point is of more than formal interest,

money income to an individual di- since it suggests that measures to reduce

minishes as income increases. (5) The inequality by altering the distribution of

total amount of income is unrelated to resources (such as social investment in

its distribution.6 the training of individuals, inheritance

taxation, etc.) may interfere less with

6 Lerner's problem is closely analogous to a rather

the optimum utilization of resources than

common problem in the theory of statistical infer-

ence, and his reasoning to the inverse probability measures that seek to redistribute in-

reasoning that was initially used in statistics. The come directly.

revolution in statistics during the last few decades

Lerner uses his analysis of the opti-

has been associated with a replacement of the loose

and inexact inverse probability reasoning by an mum distribution of income to convert

exact, operationally defined, reasoning that makes equality from an end in itself to a means

no appeal to "equal ignorance." Precisely the same

to a more fundamental and presumably

substitution will make Lerner's argument rigorous.

The problem is to determine the distribution of more obviously desirable end-namely,

income that will maximize the arithmetic sum of the the maximization of total satisfaction in

utilities received by the individuals in the society

a society. For reasons stated in the next

subject to the assumptions listed in the text.

Consider any initial unequal distribution of in- two paragraphs, Lerner's analysis seems

come. Conceptually classify the individuals by their to the reviewer rather to discredit the

(unknown) capacities for satisfaction. Each such

"satisfaction class" will contain only individuals given assumptions (I), (2), (4), and (5), that an

who have identical capacities, i.e., have identical equal distribution will maximize aggregate utility. If

utility functions. By assumption (3) the average in- a dollar is taken from an individual with a larger in-

come of the persons in each such class is the same come and given to an individual with a smaller in-

for every class. Furthermore, any redistribution of come, the former loses less utility than the latter

income among classes would invalidate assumption gains, by assumption (4); the aggregate income to be

(3), so only redistributions within these classes willdistributed is unaffected, by assumption (5), and

be consistent with the assumptions. Moreover, by the utility schedules of the two individuals, which

assumption (2), changes in any one class will not were the same before the transfer, remain the same

affect any other class, so the problem reduces to theafter, by assumption (2). This completes the proof,

simpler problem of maximizing the aggregate utilitysince equal distribution within each class, given

of each satisfaction class separately. equal mean incomes of different classes, implies

For a particular satisfaction class, it is clear, equal income throughout the society.

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LERNER ON THE ECONOMICS OF CONTROL 411

maximization of total satisfaction as a dred persons in the United States are

desirable end and to suggest that equal- enormously more efficient pleasure ma-

ity is much the more fundamental of the chines than any others, so that each of

two. these would have to be given an income

An essential step in Lerner's analysis ten thousand times as large as the income

is the introduction of ignorance. Granted, of the next most efficient pleasure ma-

says Lerner, that individuals differ in chine in order to maximize aggregate

their capacities to enjoy satisfaction, that utility. Would Lerner be willing to ac-

they are not equally efficient pleasure cept the resulting division of income as

machines, there is no method of deter- optimum even though it were entirely

mining how efficient they are as pleasure consistent with all other objectives (such

machines and therefore no hope of ad- as maximization of the total to be di-

justing the amount of income to the vided) ?7

individual's efficiency. Any actual un-

equal division of income must therefore B. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

involve a random association of income There is little discussion, and that not

with innate efficiency as a pleasure ma-

systematic, of techniques for achieving

chine (assumption [3] above). Since the the equalization of income that Lerner

mistake of giving too much to an indi-

takes as the relevant formal condition

vidual is more serious (because of the as-

for an optimum. Though Lerner does

sumed diminishing marginal utility of not explicitly say so, it is a reasonable

income) than the mistake of giving too

inference that he would, in the main, re-

little, an unequal division of income

tain the existing techniques for distribut-

yields a smaller total satisfaction than

ing income via payments to owners of

an equal division.

resources for the services of those re-

Eliminate the assumption of igno-

sources. The only basic change would be

rance and the same analysis immediate-

that ownership of capital resources em-

ly yields a justification of inequality if

ployed in the collectivist sector would be

individuals do differ in capacity to en-

transferred to the government, and re-

joy satisfaction. And we must clearly be turns to these, as well as the correspond-

prepared to eliminate the assumption of ing entrepreneurial income (positive or

ignorance. The talk about capacity to

negative), would accrue to the govern-

enjoy satisfaction is just empty talk un- ment. The primary distribution to indi-

less there is at least a conceptual possi- viduals for the use of their resources

bility of determining the relative ef- might be modified by a "social dividend"

ficiency of individuals as pleasure ma- and by a personal income tax, which

chines. One could hardly take the posi- Lerner looks on with favor "where taxa-

tion that an analysis based on the tion is necessary" (p. 234), though even

capacity to enjoy satisfaction is relevant the income tax "can interfere with the

if it is impossible to determine an indi-

use of resources" (p. 235). "If it is de-

vidual's capacity, but irrelevant if it is

sired to take measures for the equaliza-

possible to do so. Suppose, then, that a

tion of income, it might be better to deal

feasible technique is devised to determine

each individual's capacity to enjoy satis- 7 This argument is essentially taken from Henry

faction. Suppose, further, that it is dis- C. Simons, Personal Income Taxation (Chicago:

covered by this technique that a hun- University of Chicago Press, i938), pp. 5-I5.

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4I2 MILTON FRIEDMAN

with that through an inheritance and dition for maintaining a stable high level

gift tax" (p. 236). of output and employment as the main-

tenance of adequate aggregate demand.

III. UNEMPLOYMENT AND FLUCTUA-

This is nowhere spelled out in fuller de-

TIONS IN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

tail, nor is there any systematic discus-

A. FORMAL CONDITIONS sion of the criteria in terms of which

The possibility of changing the amount "adequacy" is to be judged. It is implied

of resources available to society by invest- that the level of employment is the pri-

ment raises directly the problem of the mary general criterion and "full" em-

appropriate amount of investment; in- ployment the chief objective. It is im-

directly it leads into the dynamic prob- plied also, however, that there is little

lem of maintaining a stable high level of or no danger of rising prices or inflation

output in a world in which technological so long as full employment has not been

development requires continual change attained, giving the impression that

in the method of utilizing resources. Lerner considers stability of prices an

Lerner dismisses the problem of the ap- equally good criterion of the adequacy

propriate amount of investment as a of aggregate demand.

"political" problem. He devotes con-

B. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

siderable attention to the dynamic prob-

Lerner would handle the problem of

lem of fluctuations in output and invest-

maintaining adequate aggregate demand

ment. The analysis is strictly Keynesian

through "functional finance," which is

and entirely concerned with the danger

defined as "the principle of .... judging

of general equilibrium at a low level of

output and employment. Though much that are profitable even at the very low income level.

of it is worded in terms of the "trade When some investment starts, this raises income and

cycle" or "business cycle," there is no so. .. we now have a cumulative movement up-

ward . The impetus of the expansion may carry

real discussion of the business cycle. The it up to full employment or it may stop before that

explanation of "the fundamental cause level is reached" (p. 297). (Italics mine.) The in-

of the business cycle" on pages 296 and adequacy of demand alone would explain a con-

tinued low level of income; the italicized statements

297 is a masterful evasion of the prob- are clearly crucial to the conversion of the low level

lem. The "fundamental cause" turns out of income into cyclical fluctuations. The first simply

to be (I) the possibility of a stable long- starts the analysis going; the other two do no more

than to assert that there is a cycle. In terms of

run level of low output and employment Lerner's analysis alone, one would expect the "crisis

and (2) the fact that there is a business and depression" to stop at the low level of employ-

cycle.' ment that can be permanently maintained in light

of the inadequacy of demand. If this occurred, no

Lerner therefore states the formal con- opportunities for investment would accumulate,

8 "The fundamental cause of the business cycle is since current investment would exploit all the limited

the inadequacy of demand" (p. 296). "At an income opportunities for investment currently becoming

corresponding to full employment the gap between available. In order to get a cycle it is essential that

income and equilibrium consumption is very large. the decline be "cumulative" and go further than the

.... This level of income can be maintained only if low level of employment that the inadequate de-

there is sufficient investment to fill the gap. But thismand would permanently support. But clearly the

tremendous level of investment is very much more inadequacy of demand is no explanation why this

than it is profitable to maintain for very long. If such should occur. Note that even the "inadequacy of de-

a position of full employment should be reached, the mand" is supported only by adjectives-"very

opportunities of investment would soon begin to be large," "tremendous." The numerical example

used up and investment would decline. This sets in Lerner gives-which presumably suggests what

motion the cumulative processes of crisis and depres- these adjectives mean to him-indicates very much

sion . With little investment going on for a larger savings than statistical evidence suggests as

long time, opportunities for investment accumulate reasonable in peacetime.

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LERNER ON THE ECONOMICS OF CONTROL 413

fiscal measures only by their effects or beginning of an increasing deficiency

the way theyfunction in society" (p. 302 that, if left alone, will lead to drastic

n.). Lerner's discussion of functional deflation. He must tell us how to know

finance is a brilliant exercise in logic. It what medicine to use when a diagnosis

strips governmental fiscal instruments to has been made, how large a dose to give,

their essentials: taxing and spending, and how long we may expect it to take

borrowing and lending, and buying and for the medicine to be effective. The

selling; and throws into sharp relief the casual reader of Lerner's book-or, for

function of each. In the process it throws that matter, of the majority of works on

into discard conventional patterns of ex- the control of the business cycle-might

pression, verbal cliches which at times suppose that these are simple questions.

embody valid implications of more sub- A glance at a few monthly time series de-

tle reasoning but which, taken by them- picting the movement of important eco-

selves, muddle analysis of the effect of nomic magnitudes, preferably subdi-

governmental actions. Reading Lerner's vided regionally and by industries, and a

discussion of functional finance is almost brief review of attempts at retrospective

sure to induce a much-required reorgan- identification, current diagnosis, and

ization of the mental filing-case that one forecasting suggest that they are any-

has been using to classify the factors thing but simple.

involved in governmental fiscal opera- As Burns and Mitchell say:

tions. But for our present purpose the Our examination of business indexes, and

relevant question is whether the discus- less definitely of business annals, forbade us to

sion of "functional finance," besides think of business cycles "as sweeping smoothly

upward from depressions to a single peak of

being a logical exercise, is also a prescrip-

prosperity and then declining steadily to a new

tion for public policy. The answer, it

trough." On the contrary, the expansion and

seems to this reviewer, is clearly nega- contraction of many cycles seem to be inter-

tive. Once again, what looks like a pre- rupted by movements in the opposite direction,

scription evaporates into an expression and some cycles apparently have double or

of good intentions: triple peaks or troughs.9

The government decides on the buying and Not all economic activities participate

selling that is socially desirable for all sorts of in what, after the event, may be judged

particular reasons. Then it undertakes such a cyclical expansion or contraction, and

taxation and pays out such bonuses as are justi-

those that do, participate in uneven

fied by special particular circumstances.....

measure and with variable timing. Seri-

If there is insufficient total demand, so that there

is unemployment, the government will lend ous investigators seeking to establish a

money (or repay debt) to lower the rate of chronology of business cycles from past

interest until the rate of investment is at the records agree in the main about the

level it considers proper, and it will reduce

movements they regard as cyclical but

taxes or increase bonuses until the level of con-

sumption is enough, together with the invest-

differ in not unimportant detail in the

ment, to produce full employment [pp. 3I4-15]. dates they set for peaks and troughs."

9 Arthur F. Burns and Wesley C. Mitchell,

To make this into a prescription to Measuring Business Cycles (New York: National

"produce full employment," Lerner must Bureau of Economic Research, 1946), p. 7. Quota-

tell us how to know when there is "in- tion within quotation from Mitchell, Business

Cycles: The Problem and Its Setting (New York: Na-

sufficient total demand," whether this tional Bureau of Economic Research, I927), p. 329.

insufficiency is a temporary deficiency IO See Burns and Mitchell, op. cit., chap. iv, esp.

in the process of being corrected or the pp. 9I-II4.

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

414 MILTON FRIEDMAN

Contemporary interpreters of the course mate of the state of affairs and should

of business have notoriously failed not take measures of whatever magnitude

only to predict the course of business but seems appropriate; and that errors in

even to identify the current state of these actions are unimportant since they

affairs. It is not at all abnormal for some can be corrected quickly. If deflationary

to assert that we are in the early stages action is taken, and turns out to have

of deflation and others that we are enter- been unnecessary, the government can

ing into an inflation.", simply reverse itself and turn on the in-

An easy answer to these difficulties is flationary spigot; if the action was too

to say that they are irrelevant; that the drastic or not drastic enough, the govern-

government should act on its best esti- ment can then turn down or up the ap-

propriate spigot. This answer is, of

I, This has clearly been true during much of I946

course, too easy. It conflicts with the

and I947. An interesting earlier case, called to my

attention by Arthur F. Burns, is the I920-2I con- hard fact that neither government action

traction. The National Bureau of Economic Re- nor the effect of that action is instantane-

search sets January, I920, as the peak of the cycle

ous. There is likely to be a lag between

and September, I92I, as the succeeding trough

(Burns and Mitchell, op. cit., p. 78). Yet in May, the need for action and government

I920, the National City Bank said in its monthly recognition of this need; a further lag

letter on Economic Conditions, Governmental Finance,

between recognition of the need for

United States Securities: "General trade is good in all

parts of the country," and in June: "It would be a action and the taking of action; and a

mistake to assume that we are on the eve of im- still further lag between the action and

mediate deflation on a large scale." As late as

its effects. If these time lags were short

September, I920, the letter reported: "The general

business situation in our opinion has been develop- relative to the duration of the cyclical

ing in a satisfactory manner during the past month. movements government is trying to

.... The general trend is toward normal and perma-

counteract, they would be of little im-

nent conditions . The recession of industrial

activity which is under way is not severe enough to portance. Unfortunately, it is likely that

be alarming." In October: "General business is mov- the time lags are a substantial fraction

ing along in a reasonably satisfactory manner.....

of the duration of the cyclical move-

There is good reason to think that in the industries

that have been most disturbed the price reductions ments. In the absence, therefore, of a

have gone about as far as they will in the near high degree of ability to predict correctly

future." Not until the November, I920, letter was

both the direction and the magnitude of

there explicit recognition of the existence of a

serious recession. That letter reported: "The ex- required action, governmental attempts

pectations indulged in during the summer that the at counteracting cyclical fluctuations

state of depression which was affecting certain of the

through "functional finance" may easily

industries would disappear with the opening of the

fall season has not been realized; on the contrary, intensify the fluctuations rather than

business is generally receding and there is no longer mitigate them. By the time an error is

room for doubt that the country has passed the

recognized and corrective action taken,

crest of the post-war boom." The December, I920,

letter said: "The downward movement of prices of the damage may be done, and the correc-

which the first signs appeared last May, and which tive action may itself turn into a further

became quite evident in October, has become more

error.'2 This prescription of Lerner's, like

general and precipitate in the last month. The hopes

that had been entertained that the descent to a lower -2 There is much confusion on this point, largely

level would be accomplished. .... gradually .... because of an erroneous application of the sta-

have proven illusory. Rarely, if ever, has there been tistical "law of large numbers" which leads to the

so great a decline in commodity prices in so short a belief that government needs to guess right only a

time." little more than half the time to achieve some success

One of the leading and best-informed observers in mitigating cyclical fluctuations. This is incorrect.

of current business conditions thus failed to recog- If a number of random disturbances, each varying

nize the existence of one of the sharpest contractions by about the same amount, are added, their mean

on record until it was almost half over. tends to fluctuate less than any one of the disturb-

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LERNER ON THE ECONOMICS OF CONTROL 4I5

others, thus turns into an exhortation to might solve the same equations).'3 More

do the right thing with no advice how to recently, Taylor, Lange, Lerner, and

know what is the right thing to do. others have outlined the form of organ-

ization for a socialist society, discussed

IV. THE RELATION BETWEEN THE FORMAL briefly above, in which the individual

CONDITIONS FOR AN OPTIMUM AND productive units would "play" at com-

INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS petition and thereby reproduce the re-

The chief general criticism implicit in sults of a competitive-enterprise econ-

the preceding sections is that Lerner omy.'4 Another arrangement that would

writes as if it were possible to base con- accomplish the same end, given suf-

clusions about appropriate institutional ficient information, is to impose taxes

arrangements almost exclusively on and grant bounties so devised as to in-

analysis of the formal conditions for an duce monopolists to set prices at the

optimum. Unfortunately, this cannot be levels that would prevail under competi-

done. It has been long known that there tion. Lerner in this book adds yet an-

are alternative institutional arrange- other device, counterspeculation, and it

ments that would enable the formal con- would doubtless be possible to construct

ditions for an optimum to be attained. still other institutional arrangements

Furthermore, the institutional arrange- that, judged solely on a formal level,

ments adopted are likely to have im- would permit the conditions for an

portant noneconomic implications. So it optimum to be satisfied.

is necessary both to make a choice and to None of these arrangements will, of

introduce additional criteria in making course, operate perfectly in practice. The

the choice. most that can be expected is a reasonable

Some fifty years ago, Pareto pointed approximation to the economic optimum.

out that the equilibrium allocation of re- They must, therefore, be judged in part

sources in a freely competitive society by (i) the practical administrative prob-

based on private property is identical lems entailed in so operating them as to

with the allocation that should be sought approximate the economic optimum and

by a socialist state striving to achieve a (2) as a corollary, the extent to which

maximum of "ophelimity" and that, on they lend themselves to abuse, i.e., the

the formal level alone, totalitarian direc- ease with which they can be used for ob-

tion might achieve the same allocation of jectives other than the general welfare.

resources as a free price system (i.e., both Economic institutions do not operate in

a vacuum. They form part, and an ex-

ances, and in this sense, the errors tend to cancel tremely important part, of the social

out; but their sum tends to fluctuate more than any

one of the disturbances, and the larger the number

structure within which individuals live.

of disturbances added, the larger the fluctuations in They must also be judged by (3) their

the sum. The effects of countercyclical actions of noneconomic implications, of which the

government are added to, not averaged with, the

economic movements that would otherwise take

I3 Vilfredo Pareto, Cours d'&onomie politique

place. If the countercyclical actions of government

(Lausanne, i897), Vol. II, Book II, chap. ii, pars.

were entirely random disturbances, unrelated in

717-24, pp. 84-95. Pareto, of course, went further

any systematic fashion to the other movements, they

and discussed also some of the nonformal considera-

would tend to increase the amplitude of cyclical

tions appropriate to the choice.

movements. A slight ability to guess correctly would,

therefore, serve only to mitigate or eradicate this I4 Oscar Lange and Fred M. Taylor, On the Eco-

undesirable effect, and a considerable ability to nomic Theory of Socialism, ed. Benjamin E. Lippin-

guess correctly would be required to convert govern- cott (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

ment action into a stabilizing influence. 1938).

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

4i6 MILTON FRIEDMAN

political implications-the implications The controlled economy may consider that

even some sacrifice of efficiency in the allocation

for individual liberty-are probably of

of resources is worth while as a contribution

the most interest and the ethical implica-

to the safeguard of democracy, though the kind

tions the most fundamental. of government that would take this into account

As already noted, Lerner neither dis- could put up adequate safeguards even if it

were ioo per cent collectivist [pp. 84-85].

cusses nor even appears to recognize the

first two bases for judging the appro-

(But would it or could it stay the same

priateness of economic institutions. He

government if it became ioo per cent

clearly recognizes the importance of the

collectivist?)

third-indeed, he states in the Preface

It would be unfair to Lerner to end

that recognition of the importance of po-

without stressing again that the dis-

litical implications was largely respon-

tribution of space in this review is very

sible for leading him to alter the char-

different from the distribution of space in

acter of the book from a discussion of a

the book. The book is at one and the

completely collectivist society to a dis-

same time (i) an elementary text in eco-

cussion of a society which retains large

nomic principles written from a novel

elements of private property and free

point of view and emphasizing formal

enterprise-but he explicitly rules out

analysis rather than descriptive ma-

systematic discussion of political impli-

terial, (2) a tract for the times advocat-

cations. "In this study we shall not go ing a "controlled economy." Most of the

into the merits of this political issue. We

book is devoted to teaching principles,

shall assume a government that wishes to

though the tone of a tract permeates it

run society in the general social interest

all. Most of this review is devoted to the

and is strong enough to override the op-

tract.

position afforded by any sectional inter-

The proposals in the book have con-

est" (p. 6). The only other comment of

siderable suggestive value and may

any substance on this issue is a brief

stimulate others to useful and important

discussion of "the significance of private

work in developing them. The book

enterprise as one of the guarantees of the

throughout reveals Lerner's very con-

freedom of the individual." There is a

siderable gifts-his acuteness as a theo-

sound basis, he says,

rist and dialectician, his skill and

for this argument even if it is often distorted by patience in exposition, his flexibility of

fanatical capitalists who identify the freedom of

mind, his profound interest in social wel-

the individual with the license of the capitalist

fare, and his willingness to accept and

millionaire or even with the economic powers of

giant corporations ..... The liberty of the indi- courage to state what seems to him right

vidual obtained its first start in modern times social policy, regardless of precedent or

with the freeing of private enterprise and .... accepted opinion. In the reviewer's judg-

the possibility for the individual of finding a ment, however, these gifts have been im-

means of livelihood outside of employment by

perfectly realized because they have been

the state can be a check on undue subservience

to the employers who represent the state. Of employed in a vacuum and have not

course this is one only of many forces that mustbeen combined with a realistic appraisal

be developed and maintained if democracy is to of the administrative problems of eco-

be preserved and by itself it can not guarantee nomic institutions or of their social and

democracy, but anything that may contribute

political implications.

to the safeguarding of democracy is of great

value. UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

This content downloaded from

176.207.173.50 on Mon, 29 Nov 2021 12:12:13 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Corporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy ReformsFrom EverandCorporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy ReformsNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and EvolutionFrom EverandMicroeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and EvolutionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis of Internal OrganizationDocument37 pagesMarkets and Hierarchies: Analysis of Internal OrganizationRohan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Turnbull S, 1997 Corporate GovDocument27 pagesTurnbull S, 1997 Corporate GovMila Minkhatul Maula MingmilaNo ratings yet

- Economic Instituions (Wiggins Davies 2006)Document6 pagesEconomic Instituions (Wiggins Davies 2006)Anto Osorio BarahonaNo ratings yet

- The Economics of Bounded RationalityDocument17 pagesThe Economics of Bounded RationalityJeff CacerNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Potential and Problems of New Institutional Economics For Third World DevelopmentDocument16 pagesAnalysis of The Potential and Problems of New Institutional Economics For Third World DevelopmentAndrea FalcaoNo ratings yet

- Development As Institutional Change: The Pitfalls of Monocropping and The Potentials of DeliberationDocument23 pagesDevelopment As Institutional Change: The Pitfalls of Monocropping and The Potentials of DeliberationClaudia PoclabaNo ratings yet

- Economic Performance Through TimeDocument11 pagesEconomic Performance Through TimeFlorin-Robert ROBUNo ratings yet

- Wiley American Finance AssociationDocument26 pagesWiley American Finance AssociationBenaoNo ratings yet

- The New Institutionalisms in Economics and SociologyDocument27 pagesThe New Institutionalisms in Economics and Sociologymam1No ratings yet

- HamiltonDocument11 pagesHamiltonMonica BurgosNo ratings yet

- StractureDocument41 pagesStracturepappujanNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Capabilities82Document38 pagesDynamic Capabilities82Maimana AhmedNo ratings yet

- Prince-The Motivational Assumption For Accounting TheoryDocument11 pagesPrince-The Motivational Assumption For Accounting TheoryNeven BorakNo ratings yet

- The Nature of FirmDocument21 pagesThe Nature of FirmMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- Douglass C. North - Economic Performance Through TimeDocument11 pagesDouglass C. North - Economic Performance Through TimeHugo SerafiniNo ratings yet

- Fuerza de Los Vínculos y Relaciones en InnovaciónDocument34 pagesFuerza de Los Vínculos y Relaciones en InnovaciónJuan Camilo ZapataNo ratings yet

- Disclosing New Worlds: A Role For Social and Environmental Accounting and AuditingDocument25 pagesDisclosing New Worlds: A Role For Social and Environmental Accounting and AuditingAnggrainni RahayuNo ratings yet

- The Role of Institutions in DevelopmentDocument39 pagesThe Role of Institutions in DevelopmentMohammad FouadNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes For Political Economy - 2003 Class NotesDocument251 pagesLecture Notes For Political Economy - 2003 Class Notesaleach1989No ratings yet

- Suggestions For A Sociological Approach To The Theory of OrganizationsDocument16 pagesSuggestions For A Sociological Approach To The Theory of OrganizationsAmani MoazzamNo ratings yet

- Helfat - The Behavior and Capabilities of FirmsDocument19 pagesHelfat - The Behavior and Capabilities of FirmsSHAMARY NATHALY NTOSNo ratings yet

- Uzzi 1997 Social Structure & EmbeddednessDocument34 pagesUzzi 1997 Social Structure & EmbeddednessPaola RaffaelliNo ratings yet

- Why Law, Economics, and OrganizationDocument48 pagesWhy Law, Economics, and OrganizationvenkysscribeNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Global Financial Crisis Through an Institutional Theory LensDocument10 pagesUnderstanding the Global Financial Crisis Through an Institutional Theory LenssuhaibriazNo ratings yet

- Campbell - Why Would Corporations Behave in Socially Responsible Ways An Institutional Theory of Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument23 pagesCampbell - Why Would Corporations Behave in Socially Responsible Ways An Institutional Theory of Corporate Social ResponsibilitySteven consueloNo ratings yet

- The Social Dimensions of EntrepreneurshipDocument44 pagesThe Social Dimensions of EntrepreneurshipPablo SelaNo ratings yet

- 1981 TuzzolinoDocument9 pages1981 TuzzolinoA CNo ratings yet

- Convergence of Corporate Governance Systems: Good or Bad?': in 2000. ButDocument11 pagesConvergence of Corporate Governance Systems: Good or Bad?': in 2000. ButAjay Singh MauryaNo ratings yet

- Organization Theory For Leaders: Frank R. HunsickerDocument6 pagesOrganization Theory For Leaders: Frank R. HunsickerYAYASAN INSAN NUSANTARANo ratings yet

- Bureaucracy: Understanding Its Problems and ContextDocument16 pagesBureaucracy: Understanding Its Problems and ContextEugenia WahlmannNo ratings yet

- Economic Growth and Social CapitalERSA WP08 Interest-LibreDocument41 pagesEconomic Growth and Social CapitalERSA WP08 Interest-LibreRafael PassosNo ratings yet

- (Douglass North) - Economic Performance Through Time PDFDocument13 pages(Douglass North) - Economic Performance Through Time PDFRogelio SimonNo ratings yet

- Lowi - Decision Making Vs Policy MakingDocument13 pagesLowi - Decision Making Vs Policy MakingJosé Henrique NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Aula 5. Item 2. Theory of The FirmDocument56 pagesAula 5. Item 2. Theory of The FirmJosie TotesNo ratings yet

- Talcot Parsons (1956) .Suggestions For A Sociological Approach To The Theory of OrganizationsDocument24 pagesTalcot Parsons (1956) .Suggestions For A Sociological Approach To The Theory of OrganizationsAmani MoazzamNo ratings yet

- Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership StructureDocument55 pagesTheory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership StructureBara HakikiNo ratings yet

- Received January 1976, Revised Version Received July 1976Document55 pagesReceived January 1976, Revised Version Received July 1976nadiaNo ratings yet

- What Is A Collaborative EconomyDocument7 pagesWhat Is A Collaborative EconomyageNo ratings yet

- What Is A Collaborative EconomyDocument7 pagesWhat Is A Collaborative EconomyageNo ratings yet

- Theory: of TheDocument69 pagesTheory: of TheJulyanto Candra Dwi CahyonoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Financial Economics Volume 3 Issue 4 1976 (Doi 10.1016 - 0304-405x (76) 90026-x) Michael C. Jensen William H. Meckling - Theory of The Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and OwnersDocument56 pagesJournal of Financial Economics Volume 3 Issue 4 1976 (Doi 10.1016 - 0304-405x (76) 90026-x) Michael C. Jensen William H. Meckling - Theory of The Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and OwnersDiploma IV KeuanganNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Management For Organizational CohesionDocument6 pagesKnowledge Management For Organizational CohesionElias BounjaNo ratings yet

- 2005 - Davis - New Directions in Corporate Governance.Document21 pages2005 - Davis - New Directions in Corporate Governance.ahmed sharkasNo ratings yet

- The Theoretical Framework For Corporate GovernanceDocument21 pagesThe Theoretical Framework For Corporate GovernanceomarelzainNo ratings yet

- Market and HierarchiesDocument10 pagesMarket and HierarchiesRohan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Norma EtikaDocument252 pagesNorma EtikaastroNo ratings yet

- The Past and Present of The Theory of The Firm: A Historical Survey of The Mainstream Approaches To The Firm in EconomicsDocument207 pagesThe Past and Present of The Theory of The Firm: A Historical Survey of The Mainstream Approaches To The Firm in Economicspwalker_25No ratings yet

- Coase 1937, The Nature of The FirmDocument10 pagesCoase 1937, The Nature of The FirmLuuk StaalNo ratings yet

- 472management Accounting and Corporate Governance An Institutional Interpretation of The Agency ProblemDocument20 pages472management Accounting and Corporate Governance An Institutional Interpretation of The Agency ProblemMohammad Al-HalalmehNo ratings yet

- Do Firms Really PlanDocument26 pagesDo Firms Really PlanmarcosaalacerdaNo ratings yet

- Suntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines London School of EconomicsDocument21 pagesSuntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines London School of EconomicsFelicia AprilianiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Accting Res - 2021 - Hanlon - Behavioral Economics of Accounting A Review of Archival Research On IndividualDocument65 pagesContemporary Accting Res - 2021 - Hanlon - Behavioral Economics of Accounting A Review of Archival Research On IndividualNur Hidayah K FNo ratings yet

- S G W - S L .V.: Chriften DER Esellschaft FÜR Irtschafts UND Ozialwissenschaften DES Andbaues EDocument11 pagesS G W - S L .V.: Chriften DER Esellschaft FÜR Irtschafts UND Ozialwissenschaften DES Andbaues ERizali DjaelangkaraNo ratings yet

- Corporate Responsibility and The Good Society - From Economics To EcologyDocument14 pagesCorporate Responsibility and The Good Society - From Economics To EcologyDaniela LouraçoNo ratings yet

- BUS558 2009A Ch1-4Document15 pagesBUS558 2009A Ch1-4Rayyan SNo ratings yet

- Barr 1992 JEL5Document98 pagesBarr 1992 JEL5eugenia wechslerNo ratings yet

- Markets, Organizations and Information: Beyond the Dichotomies of Industrial OrganizationFrom EverandMarkets, Organizations and Information: Beyond the Dichotomies of Industrial OrganizationNo ratings yet

- Finn Paniagua - Citizens and The State Amid Social UnrestDocument1 pageFinn Paniagua - Citizens and The State Amid Social UnrestPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Nobel Prize.List.Pablo. based on their contributionsDocument1 pageNobel Prize.List.Pablo. based on their contributionsPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Pablo - Anatomy.of - Externalities.P-M-R (1) - ImDocument11 pagesPablo - Anatomy.of - Externalities.P-M-R (1) - ImPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- The Stability Properties of Monetary ConstitutionsDocument26 pagesThe Stability Properties of Monetary ConstitutionsPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- 19.quasimarket FailureDocument16 pages19.quasimarket FailurePrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Don Lavoie's National Economic Planning InsightsDocument16 pagesDon Lavoie's National Economic Planning InsightsPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Paniagua Review Essay GoodspeedDocument17 pagesPaniagua Review Essay GoodspeedPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Petition and DemocracyDocument6 pagesPetition and DemocracyPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Bank Bargains and Entangled PolEconDocument31 pagesBank Bargains and Entangled PolEconPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Defining Economics: The Long Road To Acceptance of The Robbins DefinitionDocument16 pagesDefining Economics: The Long Road To Acceptance of The Robbins DefinitionOana Camelia SerbanNo ratings yet

- Robust Political Economy: An Institutional Alternative Against Monetary Disequilibrium and Market DiscoordinationDocument37 pagesRobust Political Economy: An Institutional Alternative Against Monetary Disequilibrium and Market DiscoordinationPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Classic LiberalismDocument5 pagesClassic LiberalismPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Facto by The Untested Theorem That Market Institutions Will "Fail" in TheDocument15 pagesFacto by The Untested Theorem That Market Institutions Will "Fail" in ThePrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- The Robust Political Economy of Central Banking and Free BankingDocument18 pagesThe Robust Political Economy of Central Banking and Free BankingPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Book Review: The Great Persuasion Reinventing Free Markets Since The DepressionDocument4 pagesBook Review: The Great Persuasion Reinventing Free Markets Since The DepressionPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Monetary Phase of The Great DepressionDocument12 pagesA Review of The Monetary Phase of The Great DepressionPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Monetary Morphine and The Job MarketDocument3 pagesMonetary Morphine and The Job MarketPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- EsperantoDocument6 pagesEsperantoPrieto Pablo0% (1)

- Financial DespotismDocument3 pagesFinancial DespotismPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Joseph Alois SchumpeterDocument5 pagesJoseph Alois SchumpeterPrieto Pablo100% (1)

- Money: Natural Money, Centralized Creation, Sub-Optimality and Self-Organizing ProcessesDocument11 pagesMoney: Natural Money, Centralized Creation, Sub-Optimality and Self-Organizing ProcessesPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Cantillon EffectDocument6 pagesCantillon EffectPrieto Pablo100% (1)

- EU and Price SystemDocument5 pagesEU and Price SystemPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Money: Natural Money, Centralized Creation, Sub-Optimality and Self-Organizing ProcessesDocument11 pagesMoney: Natural Money, Centralized Creation, Sub-Optimality and Self-Organizing ProcessesPrieto PabloNo ratings yet

- CHPT 7 in Class ExercisesDocument3 pagesCHPT 7 in Class ExercisesKaran Pahwa0% (1)

- Adnan Ali CVDocument2 pagesAdnan Ali CVadnanallNo ratings yet

- Study of Distribution Channel of Asian PaintsDocument54 pagesStudy of Distribution Channel of Asian Paintssurubanna67% (3)

- Tourism Development and Its Impact On The Indian EconomyDocument11 pagesTourism Development and Its Impact On The Indian EconomyTarun MotlaNo ratings yet

- Vardhman Polytex LimitedDocument11 pagesVardhman Polytex Limitedvicky mehtaNo ratings yet

- API COD DS2 en Excel v2 1622388Document454 pagesAPI COD DS2 en Excel v2 1622388jo joNo ratings yet

- IDEA Project DharmenderDocument62 pagesIDEA Project Dharmendermss_sikarwar3812No ratings yet

- Business Taxes and Transfer Taxes ExplainedDocument65 pagesBusiness Taxes and Transfer Taxes ExplainedPrincess LimNo ratings yet

- McKinsey 7S ModelDocument7 pagesMcKinsey 7S ModelniranjanusmsNo ratings yet

- Setting up a cosmetics business in AbujaDocument12 pagesSetting up a cosmetics business in Abujafirst materials100% (1)

- F 1040 SBDocument2 pagesF 1040 SBapi-252942620No ratings yet

- Technical Problems Facing Natural Gas Industry in MalaysiaDocument3 pagesTechnical Problems Facing Natural Gas Industry in MalaysiaApril JuneNo ratings yet

- Global Employment OutlookDocument14 pagesGlobal Employment OutlookPustaka Perumahan dan Kawasan Permukiman (PIV PKP)No ratings yet

- Titman PPT CH18Document79 pagesTitman PPT CH18IKA RAHMAWATINo ratings yet

- ECCO - Course Work 11Document3 pagesECCO - Course Work 11Stoyka Bogoeva100% (2)

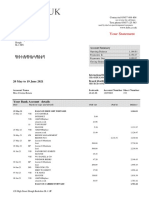

- Your Statement: 20 May To 19 June 2021Document3 pagesYour Statement: 20 May To 19 June 2021Cristina Rotaru100% (1)

- Aggregation of Income Set Off and Carry Forward of Losses 2Document21 pagesAggregation of Income Set Off and Carry Forward of Losses 2qazxswNo ratings yet

- Puschmann2017 FintechDocument8 pagesPuschmann2017 FintecharushichananaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document9 pagesPresentation 1Jagannath KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- Unemployment and InflationDocument21 pagesUnemployment and InflationShobhit SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Retail Hardware Store Business PlanDocument13 pagesRetail Hardware Store Business PlanIsaac Hassan50% (2)

- Internship Report On Portfolio ManagemenDocument67 pagesInternship Report On Portfolio Managemencharu bishtNo ratings yet

- Marketing Project - Beer Market AnalysisDocument11 pagesMarketing Project - Beer Market AnalysisIrina StefanaNo ratings yet

- Path PradarshakDocument3 pagesPath Pradarshaknisha34No ratings yet

- Child Labour and Education UKDocument78 pagesChild Labour and Education UKDina DawoodNo ratings yet

- Annual Report TB 2018Document370 pagesAnnual Report TB 2018Laura Desi SitumorangNo ratings yet

- Maximising Returns From A Retail Network Nov 2009Document5 pagesMaximising Returns From A Retail Network Nov 2009jaiganeshan89No ratings yet

- CH 11Document50 pagesCH 11Mareta Vina ChristineNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam-Adjusting EntriesDocument5 pagesMidterm Exam-Adjusting EntriesHassanhor Guro BacolodNo ratings yet

- Four Stages of Operational Competitiveness and Service BlueprintingDocument18 pagesFour Stages of Operational Competitiveness and Service BlueprintingAmanda Samaras0% (1)