Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Japanese Shop Is 1,020 Years Old. It Knows A Bit About Surviving Crises. - The New York Times

This Japanese Shop Is 1,020 Years Old. It Knows A Bit About Surviving Crises. - The New York Times

Uploaded by

nptanpta0201Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Japanese Shop Is 1,020 Years Old. It Knows A Bit About Surviving Crises. - The New York Times

This Japanese Shop Is 1,020 Years Old. It Knows A Bit About Surviving Crises. - The New York Times

Uploaded by

nptanpta0201Copyright:

Available Formats

PLAY THE CROSSWORD Account

This Japanese Shop Is 1,020 Years Old. It

Knows a Bit About Surviving Crises.

A mochi seller in Kyoto, and many of Japan’s other centuries-old

businesses, have endured by putting tradition and stability over profit

and growth.

Ichiwa has been selling grilled rice flour cakes to travelers in Kyoto, Japan, for a thousand years. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

347

By Ben Dooley and Hisako Ueno

Published Dec. 2, 2020 Updated Dec. 3, 2020, 1:59 a.m. ET

KYOTO, Japan — Naomi Hasegawa’s family sells toasted mochi out

of a small, cedar-timbered shop next to a rambling old shrine in

Kyoto. The family started the business to provide refreshments to

weary travelers coming from across Japan to pray for pandemic

relief — in the year 1000.

Now, more than a millennium later, a new disease has devastated

the economy in the ancient capital, as its once reliable stream of

tourists has evaporated. But Ms. Hasegawa is not concerned about

her enterprise’s finances.

Like many businesses in Japan, her family’s shop, Ichiwa, takes the

long view — albeit longer than most. By putting tradition and

stability over profit and growth, Ichiwa has weathered wars,

plagues, natural disasters, and the rise and fall of empires.

Through it all, its rice flour cakes have remained the same.

Naomi Hasegawa is the operator of Ichiwa. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

Such enterprises may be less dynamic than those in other

countries. But their resilience offers lessons for businesses in

places like the United States, where the coronavirus has forced

tens of thousands into bankruptcy.

ADVERTISEMENT

AD WANDRD

Ad closed by

One Bag. Every Lifestyle.

The Bag That is Always Ready For The Perfect Shot. Shop WANDRD Bags Now.

OPEN

“If you look at the economics textbooks, enterprises are supposed

to be maximizing profits, scaling up their size, market share and

growth rate. But these companies’ operating principles are

completely different,” said Kenji Matsuoka, a professor emeritus of

business at Ryukoku University in Kyoto.

Gift Subscriptions to The Times, Cooking and Games.

Starting at $15.

“Their No. 1 priority is carrying on,” he added. “Each generation is

like a runner in a relay race. What’s important is passing the

baton.”

Japan is an old-business superpower. The country is home to more

than 33,000 with at least 100 years of history — over 40 percent of

the world’s total, according to a study by the Tokyo-based Research

Institute of Centennial Management. Over 3,100 have been running

for at least two centuries. Around 140 have existed for more than

500 years. And at least 19 claim to have been continuously

operating since the first millennium.

Kyoto, seen from a park near Ichiwa. More than 33,000 businesses in Japan have been open for a century or more. Hiroko Masuike/The

New York Times

ADVERTISEMENT

Ads by

Send feedback Why this ad?

(Some of the oldest companies, including Ichiwa, cannot

definitively trace their history back to their founding, but their

timelines are accepted by the government, scholars and — in

Ichiwa’s case — the competing mochi shop across the street.)

The businesses, known as “shinise,” are a source of both pride and

fascination. Regional governments promote their products.

Business management books explain the secrets of their success.

And entire travel guides are devoted to them.

Most of these old businesses are, like Ichiwa, small, family-run

enterprises that deal in traditional goods and services. But some

are among Japan’s most famous companies, including Nintendo,

which got its start making playing cards 131 years ago, and the soy

sauce brand Kikkoman, which has been around since 1917.

To survive for a millennium, Ms. Hasegawa said, a business cannot

just chase profits. It has to have a higher purpose. In the case of

Ichiwa, that was a religious calling: serving the shrine’s pilgrims.

Ichiwa began as a way of serving pilgrims to a nearby shrine. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

Those kinds of core values, known as “kakun,” or family precepts,

have guided many companies’ business decisions through the

generations. They look after their employees, support the

community and strive to make a product that inspires pride.

PAUL KRUGMAN:A deeper look at what’s on the mind of Paul

Sign Up

Krugman, a world-class economist and opinion columnist.

For Ichiwa, that means doing one thing and doing it well — a very

Japanese approach to business.

The company has declined many opportunities to expand,

including, most recently, a request from Uber Eats to start online

delivery. Mochi remains the only item on the menu, and if you want

something to drink, you are politely offered the choice of roasted

green tea.

ADVERTISEMENT

Ads by by

Thanks. Feedback

Ad closedimproves Google ads

Send feedback Why this ad?

The mochi are made by hand and rolled in soybean powder. Hiroko They are then grilled and coated in a sweet sauce made from white

Masuike/The New York Times miso paste. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

For most of Ichiwa’s history, the women of the Hasegawa family

made the sweet snack in more or less the same way. They boiled

the rice in the water from a small spring that burbles into the

shop’s cellar, pounded it into a paste and then shaped it into balls

that they gently toasted on wooden skewers over a small cast-iron

hibachi.

The rice’s caramelized skin is brushed with sweet miso paste and

served to the shrine’s visitors hot, before the delicate treat cools

and turns tough and chewy.

Ms. Hasegawa’s great-grandmother Tome working at the The family is large, which helps the business keep going. Hiroko

shop. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times Masuike/The New York Times

Ichiwa has made a few concessions to modernity. The local health

department has forbidden the use of well water. A mochi machine

hidden in the kitchen mechanically pounds the rice, saving a few

hours of work each morning. And, after centuries of operating on

the honor system, it charges a fixed price per plate, a change it

instituted sometime after World War II as the business began to

pay more attention to its finances.

The Japanese companies that have endured the longest have often

been defined by an aversion to risk — shaped in part by past crises

— and an accumulation of large cash reserves.

It is a common trait among Japanese enterprises and part of the

reason that the country has so far avoided the high bankruptcy

rates of the United States during the pandemic. Even when they

“make some profits,” said Tomohiro Ota, an analyst at Goldman

Sachs, “they do not increase their capital expenditure.”

ADVERTISEMENT

AD OMAZE

Ad closed by

Win a Custom Wrangler

Win a 2020 Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon, Fully Customized by DeBerti

OPEN

The honor system sustained Ichiwa for hundreds of years until prices were introduced after World War

II. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

Large enterprises in particular keep substantial reserves to ensure

that they can continue issuing paychecks and meet their other

financial obligations in the event of an economic downturn or a

crisis. But even smaller businesses tend to have low debt levels

and an average of one to two months of operating expenses on

hand, Mr. Ota said.

When they do need support, financing is cheap and readily

available. Interest rates in Japan have been low for decades, and a

government stimulus package introduced in response to the

pandemic has effectively zeroed them out for most small

enterprises.

Small shinise often own their own facilities and rely on members of

the family to help keep payroll costs down, allowing them to

stockpile cash. When Toshio Goto, a professor at the Japan

University of Economics Graduate School who has written several

books on the enterprises, conducted a survey this summer of

companies that are at least 100 years old, more than a quarter said

they had enough funds on hand to operate for two years or longer.

Still, that does not mean they are frozen in time. Many started

during the 200-year period, beginning in the 17th century, when

Japan largely sealed itself off from the outside world, providing a

stable business environment. But over the last century, survival

has increasingly meant finding a balance between preserving

traditions and adapting to quickly changing market conditions.

Workers cleaning Ichiwa at the end of a day. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

For some companies, that has meant updating their core business.

NBK, a materials firm that started off making iron kettles in 1560,

is now producing high-tech machine parts. Hosoo, a 332-year-old

kimono manufacturer in Kyoto, has expanded its textile business

into home furnishings and even electronics.

ADVERTISEMENT

AD WANDRD

Ad closed by

One Bag. Every Lifestyle.

The Bag That is Always Ready For The Perfect Shot. Shop WANDRD Bags Now.

OPEN

For others, keeping up with the times can be hard, especially those,

like Tanaka Iga Butsugu, that are essentially selling tradition itself.

Tanaka Iga has been making Buddhist religious goods in Kyoto

since 885. It is famous for what its 72nd-generation president,

Masaichi Tanaka, jokingly refers to as the “Mercedes-Benz” of

butsudan — household shrines that can sell for hundreds of

thousands of dollars.

Masaichi Tanaka is the president of Tanaka Iga Butsugu, a religious-goods manufacturer in Kyoto since

885. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

The pandemic has been “tough,” he said, but the biggest challenges

faced by his company, and many others, are Japan’s aging society

and changing tastes.

Some companies have closed because the owners could not find a

successor. For Mr. Tanaka, it is getting harder and harder to

replace skilled traditional workers. Business is crimped because

fewer people nowadays go to the temples he supplies. And new

homes are rarely built with a place to put a butsudan, which

normally occupies its own special nook in a traditional Japanese-

style room with tatami flooring and sliding paper doors.

When it comes to religious tradition, there is little room for

innovation, Mr. Tanaka said. Many of his products’ designs are

nearly as old as the company. He has considered incorporating 3-D

printers into his business, but he wonders who’s going to buy items

made with one.

Katsuya Ikeda repairing a part of a Buddhist shrine at Tanaka Iga. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

ADVERTISEMENT

AD WANDRD

Ad closed by

One Bag. Every Lifestyle.

The Bag That is Always Ready For The Perfect Shot. Shop WANDRD Bags Now.

OPEN

Ichiwa is blissfully untroubled by such concerns. The family is

large, the business is small, and the only special skill needed to

grill the mochi is a high tolerance for blistering heat.

But Ms. Hasegawa, 60, admits she sometimes feels the pressure of

the shop’s history. Even though the business doesn’t provide much

of a living, everyone in the family from a young age “was warned

that as long as one of us was still alive, we needed to carry on,” she

said.

One reason “we keep going,” she added, is “because we all hate the

idea of being the one to let it go.”

The east gate of Imamiya Shrine, just steps away from Ichiwa. Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

Ben Dooley reports on Japan’s business and economy, with a special interest in social

issues and the intersections between business and politics. @benjamindooley

A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 3, 2020 in The New York Times International Edition. Order Reprints |

Today’s Paper | Subscribe

READ 347 COMMENTS

More in Business Most Popular

11 Minutes of Exercise a Day May Help

Counter the Effects of Sitting

Stephen Colbert Says Bill Barr Will Be

Missed

Heather Ainsworth for The New York Times Margeaux Walter for The New York Times 2 Women Charged With Train Terror

In Their 20s and Saving for I Don’t Want to Be the Office Near Canadian Border

Retirement: How It Started, How Grandma

It’s Going Nov. 27

Nov. 30

Trump, in Video From White House,

Delivers a 46-Minute Diatribe on the

‘Rigged’ Election

As Trump Rages, Voters in a Key

County Move On: ‘I’m Not Sweating It’

Mark Kelly Is Sworn In, Narrowing

G.O.P.’s Senate Majority

Kriston Jae Bethel for The New York Times Haruka Sakaguchi for The New York Times Noriko Hayashi for The New York Times

Biden’s New Top Economist Has a Goodbye, Blazers; Hello, A Job for Life, or Not? A Class

12 Votes Separated These House

Longtime Focus on Workers ‘Coatigans.’ Women Adjust Attire Divide Deepens in Japan

Dec. 1 to Work at Home. Nov. 27

Candidates. Then 55 Ballots Were

Dec. 1 Found.

Editors’ Picks Police Break Up 400-Person Party at

Long Island Mansion

British Hiker Goes Missing in the

Pyrenees

Rice and Beans, With an Exhilarating

Crunch

Lacey Terrell/Netflix Margeaux Walter for The New York Times Craig Frazier

Some Movies Actually Understand I Don’t Want to Be the Office This Thanksgiving, It’s Time to

Poverty in America Grandma Stop Nap-Shaming

Nov. 27 Nov. 27 Nov. 25

ADVERTISEMENT

Go to Home Page »

NEWS OPINION ARTS LIVING MORE SUBSCRIBE

Home Page Today's Opinion Today's Arts At Home Reader Center Home Delivery

World Op-Ed Columnists Art & Design Automobiles Wirecutter

Gift Subscriptions

Coronavirus Editorials Books Games Live Events

Games

U.S. Op-Ed Contributors Dance Education The Learning Network

Politics Letters Movies Food Tools & Services Cooking

Election Results Sunday Review Music Health Multimedia

Email Newsletters

New York Video: Opinion Pop Culture Jobs Photography

Corporate Subscriptions

Business Television Love Video

Education Rate

Tech Theater Magazine Newsletters

Science Video: Arts Parenting TimesMachine Mobile Applications

Sports Real Estate NYT Store Replica Edition

Obituaries Recipes Times Journeys International

Canada

Today's Paper Style Manage My Account

Español

Corrections T Magazine

中文网

Travel

© 2020 The New York Times Company NYTCo Contact Us Work with us Advertise T Brand Studio Your Ad Choices Privacy Policy Terms of Service Terms of Sale Site Map Help Subscriptions

You might also like

- Backslash - Future of Retail - 2021Document46 pagesBackslash - Future of Retail - 2021Fernanda MacielNo ratings yet

- How To Protect Yourself From Sihr Using Knowledge 1Document29 pagesHow To Protect Yourself From Sihr Using Knowledge 1baqarpubg100% (1)

- Devotion Without DeviationDocument51 pagesDevotion Without DeviationSrivatsan Parthasarathy100% (1)

- Vocabulaire Anglais Du ShoppingDocument1 pageVocabulaire Anglais Du Shoppingquereur100% (2)

- Japan's Big Bang: The Deregulation and Revitalization of the Japanese EconomyFrom EverandJapan's Big Bang: The Deregulation and Revitalization of the Japanese EconomyNo ratings yet

- Innovation Wars: Driving Successful Corporate Innovation ProgramsFrom EverandInnovation Wars: Driving Successful Corporate Innovation ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Civilian SupremacyDocument3 pagesCivilian SupremacyJomar Teneza100% (1)

- Rediscovering Japanese Business Leadership: 15 Japanese Managers and the Companies They're Leading to New GrowthFrom EverandRediscovering Japanese Business Leadership: 15 Japanese Managers and the Companies They're Leading to New GrowthNo ratings yet

- The Alchemists: The INEOS Story – An Industrial Giant Comes of AgeFrom EverandThe Alchemists: The INEOS Story – An Industrial Giant Comes of AgeNo ratings yet

- SWOT and BCG AnalysisDocument20 pagesSWOT and BCG AnalysisAmanda YuliaNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Text and Cases PDFDocument260 pagesEntrepreneurship Text and Cases PDFKhanal NilambarNo ratings yet

- Ogilvy Making Brands Matter in Turbulent Times Beyond COVID 19 Version 2.0Document35 pagesOgilvy Making Brands Matter in Turbulent Times Beyond COVID 19 Version 2.0chiranjeeb mitraNo ratings yet

- Jenny Spanish Preterito Indefinido 277-281Document5 pagesJenny Spanish Preterito Indefinido 277-281George SmithNo ratings yet

- ts310 Users Manual PDFDocument348 pagests310 Users Manual PDFrubl770622s98No ratings yet

- The Entrepreneurial MindDocument6 pagesThe Entrepreneurial MindCyrell AsidNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper On The Contest For Japan's Economic Future - Entrepreneurs vs. Corporate Giants - DelfinDocument3 pagesReflection Paper On The Contest For Japan's Economic Future - Entrepreneurs vs. Corporate Giants - Delfinjoaquin.a.dlfnNo ratings yet

- EntreprenuerDocument4 pagesEntreprenuerLou BaldomarNo ratings yet

- 3 Lessons On Business Longevity From The Oldest Company in The WorldDocument3 pages3 Lessons On Business Longevity From The Oldest Company in The WorldVhasco SiagianNo ratings yet

- DIA Journal, 1st Edition - April 2019 PDFDocument38 pagesDIA Journal, 1st Edition - April 2019 PDFviswanathNo ratings yet

- Financial Adviser - 5 Money Lessons Everyone Can Learn From DRDocument6 pagesFinancial Adviser - 5 Money Lessons Everyone Can Learn From DREmman NepacenaNo ratings yet

- CSR 2018Document46 pagesCSR 2018stasera7777No ratings yet

- Why Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?Document43 pagesWhy Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?RaghuPatilNo ratings yet

- Sight Magazine - Postcards - Inflation Brings End To Beloved 114-Year-Old Japanese CandyDocument1 pageSight Magazine - Postcards - Inflation Brings End To Beloved 114-Year-Old Japanese Candymayona hagalitaNo ratings yet

- Econ Act 2Document3 pagesEcon Act 2Ron Skibsel YbañezNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - Case-KITKAT in Japan - Sparking A Cultural RevolutionDocument12 pagesWeek 2 - Case-KITKAT in Japan - Sparking A Cultural RevolutionMoeed Saeed100% (1)

- Konbini-Nation The Rise of The Convenience Store IDocument20 pagesKonbini-Nation The Rise of The Convenience Store IprabathnilanNo ratings yet

- Revista Digital Digital Magazine Altair TeamDocument17 pagesRevista Digital Digital Magazine Altair TeamJuan José Zapata SepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- How Eco Villages Can Grow Sustainable Local EconomiesDocument6 pagesHow Eco Villages Can Grow Sustainable Local EconomiesKalogerakiGeorgiaNo ratings yet

- The FC Magazine-V6-Jan 2011Document8 pagesThe FC Magazine-V6-Jan 2011Ade OtukoyaNo ratings yet

- Addressing Society's Pain Points: An Interview With The CEO of Ayala CorporationDocument7 pagesAddressing Society's Pain Points: An Interview With The CEO of Ayala CorporationBusiness Families FoundationNo ratings yet

- A Passion For Success Practical Inspirational and Spiritual Insight From Japans Leading Entrepreneur 0070317844 9780070317840 CompressDocument200 pagesA Passion For Success Practical Inspirational and Spiritual Insight From Japans Leading Entrepreneur 0070317844 9780070317840 CompressЭнхбат М.No ratings yet

- C.rodriguez Japanese ModelDocument34 pagesC.rodriguez Japanese ModelCarol Bergonia RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Why Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?Document43 pagesWhy Does The Earth Matter To Entrepreneurs?abs shakilNo ratings yet

- Sy, Ahcy Mari P. - Session 3 Grade BoosterDocument2 pagesSy, Ahcy Mari P. - Session 3 Grade BoosterAhcy SongNo ratings yet

- Development Challenges, South-South Solutions: March 2010 IssueDocument23 pagesDevelopment Challenges, South-South Solutions: March 2010 IssueDavid SouthNo ratings yet

- Obi - Benefits and Drawbacks of Global TradeDocument10 pagesObi - Benefits and Drawbacks of Global Tradeapi-563269172No ratings yet

- "El Manifiesto Vikingo"-Reading CircleDocument2 pages"El Manifiesto Vikingo"-Reading CirclenoemiNo ratings yet

- Akio Morita: Unique Citizen in Japan, Unique in The World. EnteroDocument4 pagesAkio Morita: Unique Citizen in Japan, Unique in The World. Enteromaria fernandaNo ratings yet

- Making It For Our Country An Ethnography of Mud-DyDocument29 pagesMaking It For Our Country An Ethnography of Mud-Dypa4o gNo ratings yet

- What Is 'Shrinkflation'Document5 pagesWhat Is 'Shrinkflation'Jeon SomiNo ratings yet

- The Development of Distribution Systems in Japan Before WWIIDocument12 pagesThe Development of Distribution Systems in Japan Before WWIILeinadNo ratings yet

- Batingaw Issue36-Digital Issue PDFDocument12 pagesBatingaw Issue36-Digital Issue PDFMigranteAusNo ratings yet

- WorldTaSCforce Venture Revolution PublicDocument13 pagesWorldTaSCforce Venture Revolution PublicepipheusNo ratings yet

- Since 1970, Our GK Books Are Rated As One ofDocument3 pagesSince 1970, Our GK Books Are Rated As One ofaravindmkaranavarNo ratings yet

- We Don'T Buy It!: Nippon Suisan, Maruha and Kyokuyo'S Continuing Support For Japan'S WhalingDocument16 pagesWe Don'T Buy It!: Nippon Suisan, Maruha and Kyokuyo'S Continuing Support For Japan'S WhalingAlezNgNo ratings yet

- Trendwatching Megatrend - FreedonismDocument3 pagesTrendwatching Megatrend - FreedonismDavina GnanapushpamNo ratings yet

- Companies FixedDocument36 pagesCompanies Fixedvj113645No ratings yet

- Doing Business in JapanDocument22 pagesDoing Business in JapanSabariah Mohd DaudNo ratings yet

- The Scope Of: MarketingDocument14 pagesThe Scope Of: MarketingSatishNo ratings yet

- IB&Globalization - An IntroductionDocument28 pagesIB&Globalization - An IntroductionMoammer BhattiNo ratings yet

- Work in Progress: The Small MovementDocument12 pagesWork in Progress: The Small MovementMaría Margarita Rodríguez100% (2)

- Informal Economy: Unveiling the Resilience and Innovation of the Informal EconomyFrom EverandInformal Economy: Unveiling the Resilience and Innovation of the Informal EconomyNo ratings yet

- Ecotopia in JapanDocument12 pagesEcotopia in JapanKandylakisDimitriosNo ratings yet

- Group 5 Case On Culture PDFDocument25 pagesGroup 5 Case On Culture PDFElcied RoqueNo ratings yet

- Mr. Akira Kojima: Toward Creation of A Truly Humane CivilizationDocument8 pagesMr. Akira Kojima: Toward Creation of A Truly Humane CivilizationVincentiusArnoldNo ratings yet

- Idt 17 2Document44 pagesIdt 17 2anhchangcodon88No ratings yet

- 1.discuss 1 (Just One) Force That Drives Globalization. Your Discussion Must Not Exceed 5 Sentences. Technological ChangeDocument6 pages1.discuss 1 (Just One) Force That Drives Globalization. Your Discussion Must Not Exceed 5 Sentences. Technological ChangeAJ OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Eship Session I ReadingDocument16 pagesEship Session I ReadingRitik vermaNo ratings yet

- Bisolicious Yautia Sweets Tiamix: EntrepreneurshipDocument11 pagesBisolicious Yautia Sweets Tiamix: EntrepreneurshipafsasfgfNo ratings yet

- EntrepreneurshipDocument17 pagesEntrepreneurshipAashman ShettyNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Assignment 1Document7 pagesUnit 1 Assignment 1oriangashagazaNo ratings yet

- Isabela State University: Republic of The Philippines Roxas, IsabelaDocument17 pagesIsabela State University: Republic of The Philippines Roxas, IsabelaMarinette MedranoNo ratings yet

- Japanese PPT Tushar 015Document11 pagesJapanese PPT Tushar 015The Tushar GamesNo ratings yet

- Lifewear, Changing The World: Annual 2020Document78 pagesLifewear, Changing The World: Annual 2020Ayda KhadivaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Culture: Help or Hindrance For Business Growth?Document4 pagesJapanese Culture: Help or Hindrance For Business Growth?Arkal S Walters FNo ratings yet

- 1 What Is GlobalisationDocument9 pages1 What Is GlobalisationJennifer MarsellaNo ratings yet

- Self-Assessment Grammar and VocabDocument4 pagesSelf-Assessment Grammar and VocabBettyNo ratings yet

- Immediate Care of The NewbornDocument3 pagesImmediate Care of The NewbornAngelee OngchuaNo ratings yet

- Thông báo nộp thuế TNCNDocument3 pagesThông báo nộp thuế TNCNTrieu Thi RanhNo ratings yet

- Model Contract of Apprenticeship Training For Major/Minor ApprenticesDocument5 pagesModel Contract of Apprenticeship Training For Major/Minor ApprenticesMukesh mahto100% (2)

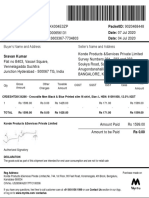

- Gstin Number: Packetid: 9020468448 Invoice Number: Date: 07 Jul 2020 Order Number: Date: 04 Jul 2020Document1 pageGstin Number: Packetid: 9020468448 Invoice Number: Date: 07 Jul 2020 Order Number: Date: 04 Jul 2020Sravan KumarNo ratings yet

- OTLDocument40 pagesOTL林昀佑No ratings yet

- Innova 2014 BC PDFDocument21 pagesInnova 2014 BC PDFGoodBikesNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing Assignment - RevisionDocument6 pagesAcademic Writing Assignment - RevisionMega PerbawatiNo ratings yet

- Most Important Principles of DirectingDocument3 pagesMost Important Principles of DirectingPriyadarshini MNo ratings yet

- HW Set Fce 2023 NewDocument201 pagesHW Set Fce 2023 NewDani CantuariasNo ratings yet

- Understanding-RAUM 2020Document17 pagesUnderstanding-RAUM 2020Gennady NeymanNo ratings yet

- Abbottabad Audit 2013Document39 pagesAbbottabad Audit 2013Lila GulNo ratings yet

- Blackberry Breakfast CakeDocument5 pagesBlackberry Breakfast Cakereema sajinNo ratings yet

- Appl Form-NTS 2016Document4 pagesAppl Form-NTS 2016patilbhushan854No ratings yet

- Verges - Lettre Ouverte À Mes Amis Algériens Devenus TortionnairesDocument79 pagesVerges - Lettre Ouverte À Mes Amis Algériens Devenus TortionnairesRyanis BennyNo ratings yet

- 05 Intro ERP Using GBI Slides MM en v2.01 ARISDocument44 pages05 Intro ERP Using GBI Slides MM en v2.01 ARISrajeshdatastageNo ratings yet

- 2005 Boian - ThesisDocument226 pages2005 Boian - ThesisFrancisco GomezNo ratings yet

- Chapter4 - Conceptual FrameworkDocument13 pagesChapter4 - Conceptual FrameworkGloria UmaliNo ratings yet

- Performance Management - at The Federal Level of Government in AustriaDocument6 pagesPerformance Management - at The Federal Level of Government in AustriadorinciNo ratings yet

- Prelude 19th CenturyDocument3 pagesPrelude 19th CenturyYulistia Rahmi Putri0% (1)

- Research Teaching StyleDocument3 pagesResearch Teaching StyleRhealene GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Beta 3 B118a Sigma Active Subwoofer Speaker SystemDocument4 pagesBeta 3 B118a Sigma Active Subwoofer Speaker SystemGabriel0% (1)

- JavelinDocument3 pagesJavelinmary go roundNo ratings yet

- Kabbala - Consciousness and The UniverseDocument14 pagesKabbala - Consciousness and The Universeapi-3717813No ratings yet