Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Economics of Public Issues 19th Edition Miller Solutions Manual

Uploaded by

danielfidelma0xzCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Economics of Public Issues 19th Edition Miller Solutions Manual

Uploaded by

danielfidelma0xzCopyright:

Available Formats

Economics of Public Issues 19th

Edition Miller Solutions Manual

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://testbankdeal.com/dow

nload/economics-of-public-issues-19th-edition-miller-solutions-manual/

Chapter 9

Kidneys for Sale

Chapter Overview

Thousands of Americans die each year waiting for an organ transplant because, since 1984, it has been

against federal law to pay for human organs. At least one purported rationale for this legal prohibition is

that it reduces the possibility of “involuntary” donations perpetrated by those who would steal an organ

from donor A to profit financially by its sale to recipient B. But advances in tissue-typing (including

DNA identification) mean that the exact identity of a donor can be quickly established; hence, the

continuation of the payment prohibition cannot be justified on the grounds of preventing involuntary

donations. In fact, it appears that permitting payment for organs would almost surely yield benefits that

substantially exceed the costs.

Descriptive Analysis

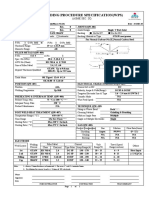

The prohibition on payments for organs acts like a price control on them in which the controlled price is

zero; that is, PC 0, as shown in Figure 9-1. The equilibrium price in a free market would be P* and the

equilibrium quantity would be Q*. Instead, we end up with only QS organs donated at a price of 0, and a

waiting list that reflects both this low donation rate and the large number of organs that are demanded at

this price (QD).

Figure 9-1 A Prohibition on Payment for Organs

Suppose we allow the price of organs to be market-determined. If all of the resulting donations are in fact

voluntary (which modern tissue-typing almost surely guarantees), then the potential gains to society are at

©2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 9: Kidneys for Sale

least as large as the area CEQS, i.e., the area between the demand and supply curve over the range from

QS to Q*. We say “at least” for two reasons. First, there is no guarantee that rationed organs will go to

their highest valued use under the current prohibition, implying that the likely gains from trade under the

current system are smaller than ACQS0. Second, the diagram does not reflect the fact that under the

current system considerable real resources are expended to allocate QS among the QD demanders,

resources that would be saved if payment were permitted.

Chapter Answers

1. Dividing $3.5 billion by 5,000 yields $700,000 per life saved, an amount well below the value

that people in America seem to place on their own lives. Keeping these people off dialysis for

three years would save (3)($80,000) = $240,000 per person, so we would need to value each life

saved at only $700,000 - $240,000 = $460,000 for the system to effectively pay for itself in

economic terms.

2. Presumably, people will be willing to offer them at lower prices where per capita income is

lowest, but arbitrage between high and low income areas should drive the price to equality across

the country. Whether low-income areas end up actually end up exporting to high-income areas

depends on the variation in demand conditions across areas. Type-2 diabetes is the most

important source of demand for transplant kidneys, and this type of diabetes tends to be higher

where per capita income is lower. Hence it is possible that fewer organs would actually end up

being transported around the country.

3. The prohibition on payment is similar to a collusive agreement among insurers that reduces the

price of this input to the transplant production process. Hence it has the potential to raise insurers’

profits. But it is unlikely that the wealth-maximizing price is zero, as effectively results from an

outright prohibition of trade. The prohibition thus creates a trade-off for the insurers:

Expenditures for the organs are lower, but (i) the insurance is now less attractive to consumers

and (ii) other health expenses (such as for dialysis) may now be higher. The greater the share of

these other costs that are covered by public plans (such as Medicare or Medicaid), the more

attractive for insurers will be the prohibition on payment. For potential transplants paid for by

taxpayers, it seems unlikely that dialysis and other costs can be shunted off onto private insurers,

so on this account taxpayers would be less inclined to favor prohibition. (There are a host of other

considerations, however. For example, if the controlled price PC 0 for organs is very far from

the private insurer optimum, it is possible that private insurers would oppose a prohibition even if

they could shift all of the added dialysis and other costs onto the private sector. And the taxpayer

calculus is affected by the fact that the public payment system generally will induce large wealth

transfers, so that voting on the prohibition is unlikely to be driven solely (or even chiefly) by

considerations of total costs or efficiency.)

4. Yes. The current system tends to allocate donated organs to recipients who live in or can quickly

(within a few hours) get to the specific geographic region where an organ is donated. Large

metropolitan areas have the most experienced transplant teams and tend to get the longest lists of

people who want organs, relative to the number of people who are donating them. Thus, people

living in such areas are more likely to die for lack of an organ than are people living in rural

areas. (This statement ignores the fact that more-experienced transplant teams tend to have a

higher success rate for transplants that do take place.) Thus, a payment system would tend to

reallocate organs from rural to urban areas, benefiting urban dwellers at the expense of people

living in rural areas.

©2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

Chapter 9: Kidneys for Sale

5. Ignoring the interest rate, shortening dialysis time saves insurers (3 years) ($80,000/year)

$240,000 per patient. Hence, if the number of transplants remained unchanged, any organ price

less than about $240,000 would be breakeven for insurers. (Actually, because the interest rate is

positive, the organs would have to be paid for immediately, and the dialysis savings are deferred,

the breakeven price would be somewhat lower than $240,000.) But, as noted in the text, if we

permit payment for organs, more will be forthcoming, implying more transplants and hence

additional (insured) costs associated with those transplants. Because the non-organ costs of a

transplant (surgical fee, operating room, hospital stay, etc.) are substantial, the net impact (on

insurer costs) of paying for organs would depend pivotally on (i) the market-clearing price of the

organs, and (ii) the number of additional transplants performed each year. Under our very simple

assumptions about reduced dialysis costs, the benefit of moving to a payment system lies not in

an absolute reduction in total costs, but in an increase in costs that is (we assert) small relative to

the benefits (fewer premature deaths, less suffering) that result.

6. In general, there are positive costs (time, psychic, or otherwise) of choosing to go contrary to the

default provision in any system. Under any system it is thus cheaper to accept the default. Under

“opt-in” people are therefore more likely to accept the default of “out” (or “no donation”). Under

“opt-out” they are more likely to accept the default of “in” or (“yes donation”). Hence, moving to

an opt-out system would be expected to increase the supply of donated organs.

©2016 Pearson Education, Inc.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- MOI Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesMOI Lesson PlanPreeti KumariNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Swot Analysis Arifinjr Graphic Design Firm: Executive SummaryDocument3 pagesSwot Analysis Arifinjr Graphic Design Firm: Executive SummarySri WaluyoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Sibunag River Development Project: Industry Sector: Business Type: Location TypeDocument4 pagesSibunag River Development Project: Industry Sector: Business Type: Location Typeemma gallosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 PowerpointDocument14 pagesChapter 1 and Chapter 2 Powerpointapi-252892423No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 01 AR PFMEA - TemplateDocument3 pages01 AR PFMEA - TemplateAndrew DoNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Full Download Social Problems in A Diverse Society 6th Edition Diana Kendall Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Social Problems in A Diverse Society 6th Edition Diana Kendall Test Bankpanorarubius100% (29)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Orca Share Media1676505355563 7031773118863093717Document42 pagesOrca Share Media1676505355563 7031773118863093717Charls Aron ReyesNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Letter of RecommendationDocument1 pageLetter of RecommendationIsaac Kocherla100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Rocna and Vulcan Anchor DimensionsDocument2 pagesRocna and Vulcan Anchor DimensionsJoseph PintoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- ASW 0822 Smart Watch With Sleep Function User Guide V10Document2 pagesASW 0822 Smart Watch With Sleep Function User Guide V10Se Jin CoohNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Welding Procedure Specification (WPS) : (Asme Sec. Ix)Document1 pageWelding Procedure Specification (WPS) : (Asme Sec. Ix)Ahmed Lepda100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Inventory Management System VB6Document7 pagesInventory Management System VB6PureNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- PTE Academic - Strategies For Summarize The Written TextDocument9 pagesPTE Academic - Strategies For Summarize The Written TextPradeep PaudelNo ratings yet

- Examen EESDocument16 pagesExamen EESManu LlacsaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Case Study MtotDocument15 pagesCase Study MtotDotecho Jzo EyNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Mouthwash, PEG, Sulfate, Betaine FreeDocument2 pagesMouthwash, PEG, Sulfate, Betaine FreerekhilaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Arkansas DispensariesDocument6 pagesArkansas DispensariesAdam ByrdNo ratings yet

- Basic Electronics New - 3110016Document4 pagesBasic Electronics New - 3110016Sneha PandyaNo ratings yet

- Penilaian Kelayakan Usaha Mikro Dengan Kredit Skoring Dan Pengaruhnya Terhadap Pembiayaan Bermasalah Best Practice Lembaga Keuangan Di IndonesiaDocument12 pagesPenilaian Kelayakan Usaha Mikro Dengan Kredit Skoring Dan Pengaruhnya Terhadap Pembiayaan Bermasalah Best Practice Lembaga Keuangan Di IndonesiaRiantriaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Import FinalDocument5 pagesImport FinalRaza AliNo ratings yet

- Eatclub D5Z1X6Document1 pageEatclub D5Z1X6Devansh nayakNo ratings yet

- REC4281GDocument307 pagesREC4281GadrianahoukiNo ratings yet

- D.ANDAN PS-PROJECT WATCH ActionPlan 2018-2019Document3 pagesD.ANDAN PS-PROJECT WATCH ActionPlan 2018-2019Maria Fe PanuganNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Raymond V. Schoder, Vincent C. Horrigan, Leslie Collins Edwards - A Reading Course in Homeric Greek, Book 2-Focus Publishing (2008) PDFDocument134 pagesRaymond V. Schoder, Vincent C. Horrigan, Leslie Collins Edwards - A Reading Course in Homeric Greek, Book 2-Focus Publishing (2008) PDFSamarul MeuNo ratings yet

- Readings in Philippine History-CeDocument11 pagesReadings in Philippine History-Cedeluna.jerremieNo ratings yet

- Bài Kt 2 Biên Dịch 1-LiêmDocument10 pagesBài Kt 2 Biên Dịch 1-LiêmNguyen Loan100% (1)

- Healthcare SCM in Malaysia - Case StudyDocument10 pagesHealthcare SCM in Malaysia - Case StudyHussain Alam100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Final CV-Europass-20190916-MezakMatijević-EN (2) - Kopija PDFDocument4 pagesFinal CV-Europass-20190916-MezakMatijević-EN (2) - Kopija PDFMirela Mezak StastnyNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Transportation Science and TechnologyDocument11 pagesInternational Journal of Transportation Science and TechnologyIrvin SmithNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Strategies For Small BusinessDocument11 pagesDynamic Strategies For Small BusinessBusiness Expert Press0% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)