Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Debate About The Earliest Calendars: Rudimentary

Uploaded by

huhumaggie0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views4 pagesOriginal Title

123

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views4 pagesDebate About The Earliest Calendars: Rudimentary

Uploaded by

huhumaggieCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Debate about the Earliest Calendars

►Some researchers believe that we can trace the

written calendar back more than 20,000 years to the last

ice age. In particular, Alexander Marshack has interpreted

cut marks found on bits of bone from central Africa and

Paleolithic caves in France to be rudimentary forms of an

early lunar calendar. The evidence lies in distinct clusters

of cut marks on the bones – marks that could not have

been by chance. The marks must have been made by

using a sharp cutting tool or by twisting a pointed object to

form a hole in the surface of the bones. According to

Marshack, each mark represents a day and these marks

are grouped in patterns of 14 or 15 days. This interval

would correspond to the times between the first sighting of

a crescent moon and the full moon, and the interval

between a full moon and the beginning a new moon cycle.

According to Marshack, there would have been

several motives for keeping a lunar record. A major

portion of the lunar-phase cycle provides extended light

for accomplishing many useful activities. Also, it helps to

plan if one knows or can anticipate when additional

daylight will come. Keeping track of lunar events would

offer the Paleolithic inhabitants of western Europe a

means of abstractly correlating what Marshack calls “time-

factored” events – those that occur sequentially in a

predictable manner – through a process that lends itself

readily to measurement. These notations could represent

the foundation of the associative process – the first step in

the evolution of traditional writing, where a mark stands for

a thing, in this case, one day. Though the best-known

bone calendar stretches but two and a half months, an

extended series of such records could have led early

hunter-gatherers to deduce that the period from human

conception to birth was nine moons; that after two moons,

a particular supply of berries would dry up; or that after

every 12 or 13 moons, all the nearby streams would swell

to capacity.

Psychologically, it is comforting to think that the use of

symbols, for example, in writing might go back such a long

way. To imagine that our earliest ancestors were abstract

thinkers like us offers a broader and higher historical

pyramid to support our modern accomplishments. Though

his basic ideas about the beginning of the arithmetic

intellect in humans are accepted by a majority of

anthropologists, Marshack’s work on lunar calendars,

even after 30 years, remains somewhat controversial.

Some critics say permanent calendar keeping is not

consistent with what we know about the level of

conceptual sophistication of these early people. Counting

the days would have been too narrow and too abstract an

idea for them to employ. Besides, cave dwellers did not

need to count days. They knew when to hunt, when to

gather, and they certainly could tell when the extended

light of the moon would come, simply by spotting the

moon after sunset. Why bother to write it all down? The

supposed benefits of Marshack’s lunar calendars would

have amounted to unnecessary intellectual baggage in the

seminomadic life of early peoples.

Other opponents have suggested that Marshack’s

bones contain no ordered pattern at all, that he has not

provided enough examples, and that those he offers

include a lot of unsupported interpretations. Are these

marks only decorations, or were the bones simply tool-

sharpening devices? Slash marks along the edges of

some of Marshack’s bones resemble the knife-sharpening

cuts made by soldiers that can be seen on the stone

pillars throughout the Nile valley. Likewise, early people

could have used bones as a means to sharpen the point

of a tool rather than to record days in the lunar cycle.

Recent experimentation with stone and bone tools

suggests that the multiple markings that appear on

Marshack’s bones could have been made without much

effort in a few hours. Therefore, if there is a pattern, it may

be that only the overall design made in few hours was

important, in which case the pattern would not consist of

individually meaningful marks for days.

These considerations can be taken to argue against the

calendar hypothesis, though they do not disprove it.

You might also like

- Davidson Review of Marshack Roots AA 1993Document4 pagesDavidson Review of Marshack Roots AA 1993lucero2002No ratings yet

- On The Possible Discovery of Precessional Effects in Ancient AstronomyDocument20 pagesOn The Possible Discovery of Precessional Effects in Ancient AstronomyAtasi Roy MalakarNo ratings yet

- Paper Inggris Tugas 2Document8 pagesPaper Inggris Tugas 2Rifa adawiyyahNo ratings yet

- Thinking About Archaeoastronomy PDFDocument28 pagesThinking About Archaeoastronomy PDFPron GoesNo ratings yet

- Great AstronomersDocument161 pagesGreat AstronomersBasitNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Planet MarsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Planet Marsnidokyjynuv2100% (1)

- New Look at The Modern Codification of TDocument27 pagesNew Look at The Modern Codification of TMiriam CunhaNo ratings yet

- Astrotheology of The AncientsDocument6 pagesAstrotheology of The AncientsDonnaveo Sherman100% (2)

- Aveni Archaeoastronomy in The Ancient Americaa Anthony F.Document43 pagesAveni Archaeoastronomy in The Ancient Americaa Anthony F.Michael TipswordNo ratings yet

- LeonardoDocument11 pagesLeonardorgurav806No ratings yet

- Astronomy NewDocument221 pagesAstronomy NewMina VukNo ratings yet

- Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost CivilizationsFrom EverandEchoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost CivilizationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Mars Research Paper FreeDocument5 pagesMars Research Paper Freeqxiarzznd100% (1)

- The Abyss of Time: Unraveling the Mystery of the Earth's AgeFrom EverandThe Abyss of Time: Unraveling the Mystery of the Earth's AgeNo ratings yet

- Emmeline M. Plunket - Ancient Calendars and ConstellationsDocument324 pagesEmmeline M. Plunket - Ancient Calendars and ConstellationsSKHMT100% (1)

- Zodiac Signs ReserchDocument29 pagesZodiac Signs ReserchShubham Sharma100% (1)

- Literature Review Example AstronomyDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Example Astronomydhjiiorif100% (1)

- Astronomy in India.Document11 pagesAstronomy in India.Aarushi GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Stargazer's Guide: How to Read Our Night SkyFrom EverandThe Stargazer's Guide: How to Read Our Night SkyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (7)

- Kragh, Helge - The Moon That Wasn't The Saga of Venus' Spurious Satellite (2008)Document210 pagesKragh, Helge - The Moon That Wasn't The Saga of Venus' Spurious Satellite (2008)rambo_style19100% (2)

- ThetimecapsuleDocument17 pagesThetimecapsulepalefatos2993No ratings yet

- Ancient Astronomy - Phanesh Babu PDFDocument12 pagesAncient Astronomy - Phanesh Babu PDFAranykoremberNo ratings yet

- Sprajc - Astronomy and Its Role in Ancient Mesoamerica PDFDocument9 pagesSprajc - Astronomy and Its Role in Ancient Mesoamerica PDFwerunomNo ratings yet

- About PrecessionDocument4 pagesAbout PrecessionAkshNo ratings yet

- About PrecessionDocument4 pagesAbout PrecessionMarko KovačNo ratings yet

- Tugas Prinsip StratigrafiDocument102 pagesTugas Prinsip StratigrafiMahasinul FathaniNo ratings yet

- Making Time Out of SpaceDocument14 pagesMaking Time Out of SpaceRobert Bonomo100% (1)

- Daniel Rosenberg - Marking TimeDocument7 pagesDaniel Rosenberg - Marking TimeSamuearlNo ratings yet

- The Geologic Time ScaleDocument10 pagesThe Geologic Time ScaleDinarKhairunisaNo ratings yet

- Mayan Calendar ExplainedDocument9 pagesMayan Calendar Explainedbresail40% (1)

- Astronomy Timelines ReviewerDocument1 pageAstronomy Timelines Reviewerah1805799No ratings yet

- 2010 Astrotheology Calendar PDFDocument49 pages2010 Astrotheology Calendar PDFAlberto Bolocan100% (2)

- Third Thoughts: The Universe We Still Don’t KnowFrom EverandThird Thoughts: The Universe We Still Don’t KnowRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (5)

- Paul D. Spudis - The Once and Future MoonDocument200 pagesPaul D. Spudis - The Once and Future Moonluigirovatti1No ratings yet

- Man and His Cosmic EnvironmentDocument7 pagesMan and His Cosmic EnvironmentOnyedika Nwankwor100% (4)

- Sans Nom 1Document4 pagesSans Nom 1JULIEN CandiceNo ratings yet

- 'U.F.O.Investigator: Thecase ForlifeonmarsDocument8 pages'U.F.O.Investigator: Thecase ForlifeonmarsedicioneshalbraneNo ratings yet

- Astronomy of Ancient CulturesDocument80 pagesAstronomy of Ancient Culturesquijota100% (5)

- The Material Culture of Astronomy in Daily LifeDocument34 pagesThe Material Culture of Astronomy in Daily Lifejhty2112No ratings yet

- Calendars and Astronomic CeilingsDocument106 pagesCalendars and Astronomic Ceilingstormael_56No ratings yet

- Decoding the Message of the Pulsars: Intelligent Communication from the GalaxyFrom EverandDecoding the Message of the Pulsars: Intelligent Communication from the GalaxyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Ancient Egyptian Astronomy - Sarah Symons 1999 ThesisDocument230 pagesAncient Egyptian Astronomy - Sarah Symons 1999 ThesisZyberstorm100% (3)

- Discovery Issues Resolution Naga NotesDocument7 pagesDiscovery Issues Resolution Naga NotesNagaPrasannaKumarKakarlamudi100% (1)

- A Brand Building Literature ReviewDocument17 pagesA Brand Building Literature ReviewUdaya Kumar SNo ratings yet

- Manual ViscosimetroDocument55 pagesManual ViscosimetroLUIS XV100% (1)

- Injection Machine RobotDocument89 pagesInjection Machine Robotphild2na250% (2)

- Case Study Sustainable ConstructionDocument5 pagesCase Study Sustainable ConstructionpraisethenordNo ratings yet

- The Advanced Formula For Total Success - Google Search PDFDocument2 pagesThe Advanced Formula For Total Success - Google Search PDFsesabcdNo ratings yet

- Role of ICT & Challenges in Disaster ManagementDocument13 pagesRole of ICT & Challenges in Disaster ManagementMohammad Ali100% (3)

- 11 Technical Analysis & Dow TheoryDocument9 pages11 Technical Analysis & Dow TheoryGulzar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Power Meditation: by Mahaswami MedhiranandaDocument7 pagesPower Meditation: by Mahaswami Medhiranandaanhadbalbir7347No ratings yet

- Data MiningDocument14 pagesData MiningRavi VermaNo ratings yet

- Eng 105 S 17 Review RubricDocument1 pageEng 105 S 17 Review Rubricapi-352956220No ratings yet

- Researchpaper Parabolic Channel DesignDocument6 pagesResearchpaper Parabolic Channel DesignAnonymous EIjnKecu0JNo ratings yet

- Build Web Application With Golang enDocument327 pagesBuild Web Application With Golang enAditya SinghNo ratings yet

- Sequential StatementDocument12 pagesSequential Statementdineshvhaval100% (1)

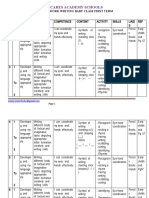

- Scheme of Work Writing Baby First TermDocument12 pagesScheme of Work Writing Baby First TermEmmy Senior Lucky100% (1)

- Nexlinx Corporate Profile-2019Document22 pagesNexlinx Corporate Profile-2019sid202pkNo ratings yet

- GIS Project ProposalDocument2 pagesGIS Project ProposalKevin OdonnellNo ratings yet

- DistillationDocument8 pagesDistillationsahil khandelwalNo ratings yet

- T50 - SVPM - 2014 - 13 - Risk Assessment in Ship Hull Structure Production Using FMEADocument13 pagesT50 - SVPM - 2014 - 13 - Risk Assessment in Ship Hull Structure Production Using FMEACiutacu AndreiNo ratings yet

- Rebecca Wilman 17325509 Educ4020 Assessment 3Document6 pagesRebecca Wilman 17325509 Educ4020 Assessment 3api-314401095No ratings yet

- DfgtyhDocument4 pagesDfgtyhAditya MakkarNo ratings yet

- Kinetic - Sculpture FirstDocument3 pagesKinetic - Sculpture FirstLeoNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Self-ConceptDocument13 pagesGender Differences in Self-Conceptmaasai_maraNo ratings yet

- It'S Not A Lie If You Believe It: LyingDocument2 pagesIt'S Not A Lie If You Believe It: LyingNoel ll SorianoNo ratings yet

- Fhwa HRT 04 043Document384 pagesFhwa HRT 04 043hana saffanahNo ratings yet

- Telephone Operator 2021@mpscmaterialDocument12 pagesTelephone Operator 2021@mpscmaterialwagh218No ratings yet

- Discrete Mathematics Sets Relations FunctionsDocument15 pagesDiscrete Mathematics Sets Relations FunctionsMuhd FarisNo ratings yet

- 12.22.08 Dr. King Quotes BookletDocument16 pages12.22.08 Dr. King Quotes BookletlamchunyienNo ratings yet