Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Friskin TextTchaikovskysB 1969

Friskin TextTchaikovskysB 1969

Uploaded by

Gini Yu-Fang TuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Friskin TextTchaikovskysB 1969

Friskin TextTchaikovskysB 1969

Uploaded by

Gini Yu-Fang TuCopyright:

Available Formats

The Text of Tchaikovsky's B♭ Minor Concerto

Author(s): James Friskin and P. Tchaikovsky

Source: Music & Letters , Apr., 1969, Vol. 50, No. 2 (Apr., 1969), pp. 246-251

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/732535

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Music & Letters

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE TEXT OF TCHAIKOVSKY'S Bb MINOR

CONCERTO

BY JAMES FRISKIN1

ON 2I January 1878 Tchaikovsky wrote a letter to N

Meck, the rich railway engineer's widow, with whom fo

he exchanged an intimate correspondence while consisten

a meeting. His letter was a long one, and in it he told he

than three years previously he had written a piano

went on to describe his interview, immediately after th

of the work, with Nicholas Rubinstein, head of the Moscow

Conservatoire of Music, where he was a member of the teaching

staff. It is easy to imagine, on reading his somewhat emotional

account of the incident, why he seems to have been unable to bring

himself to mention it to Mme. von Meck before. He had written her

many letters during the preceding year. He had confided to her

much-though by no means all-of his very complicated private

life. He knew she was ardently interested in everything that

concerned his music. But the encounter with Rubinstein had been a

humiliating one; and it had obviously rankled for years.

The letter, which has often been reproduced in various transla-

tions, is worth giving almost in entirety:

As I am not a pianist, it was necessary to consult some virtuoso as to

what might be ineffective, impracticable, and ungrateful in my

technique. I needed a severe, but at the same time friendly, critic, to

point out in my work these external blemishes only. Without going

into details, I must mention the fact that some inward voice warned

me against the choice of Nicholas Rubinstein as a judge of the

technical side of my composition. However, as he was not only the

best pianist in Moscow, but also a first-rate all-round musician, and

knowing that he would be deeply offended if he heard I had taken my

concerto to anyone else, I decided to ask him to hear the work and

give me his opinion upon the solo parts. It was on Christmas Eve,

I874. We were invited to Albrecht's house and, before we went,

Nicholas Rubinstein proposed I should meet him in one of the

classrooms of the Conservatoire to go through the concerto. I arrived

with my manuscript, and Rubinstein and Hubert soon appeared...

I played the first movement. Never a word, never a single remark.

Do you know the awkward and ridiculous sensation of putting before

a friend a meal which you have cooked yourself, which he eats-and

holds his tongue? Oh, for a single word, for friendly abuse, for

anything to break the silence! For God's sake say something! But

1 The author of this article was working on it shortly before his death in X967. It has

been completed by his widow, with the help of Mr. Malcolm Frager. The illustrations are

reproduced by permission of Admiral Hubert Dannreuther-ED.

246

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

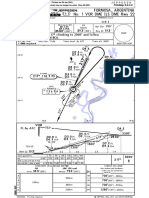

Tchaikovsky's Bb minor concerto (first movement)

I

(bars I-20)

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

II

(bars 67-79)

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Rubinstein never opened his lips. He was preparing his thunderbolt,

and Hubert was waiting to see which way the wind would blow...

Rubinstein's silence was eloquent... I gathered patience, and

played the concerto straight through to the end. Still silence.

"Well?" I asked, and rose from the piano. Then a torrent broke

from Rubinstein's lips. Gentle at first, gathering volume as it pro-

ceeded, and finally bursting into the fury of a Jupiter-Tonans.

My concerto was worthless, absolutely unplayable; the passages so

broken, so disconnected, so unskilfully written, that they could

not even be improved; the work itself was bad, trivial, common;

here and there I had stolen from other people; only one or two pages

were worth anything; all the rest had better be destroyed, or entirely

rewritten. "For instance, that?" "And what meaning is there in

this?" Here the passages were caricatured on the piano. "And look

there: is it possible that anyone could? etc., etc., etc." But the chief

thing I cannot reproduce: the tone in which all this was said. An

independent witness of this scene must have concluded I was a

talentless maniac, a scribbler with no notion of composing, who had

ventured to lay his rubbish before a famous man. Hubert was quite

overcome by my silence and was surprised, no doubt, that a man who

had already written so many works, and was professor of composition

at the Conservatoire, could listen calmly and without contradiction

to such a jobation, such as one would hardly venture to address to a

student before having gone through his work very carefully...

I was not only astounded, but deeply mortified, by the whole

scene. I require friendly counsel and criticism; I shall always be glad

of it, but there was no trace of friendliness in the whole proceedings.

It was a censure delivered in such a form that it cut me to the quick.

I left the room without a word and went upstairs. I could not have

spoken for anger and agitation. Presently Rubinstein came to me and,

seeing how upset I was, called me into another room. There he

repeated that my concerto was impossible, pointed out many places

where it needed to be completely revised, and said that if I would

suit the concerto to his requirements he would bring it out at his

concert. "I shall not alter a single note", I replied, "I shall publish the

work precisely as it stands". This intention I actually carried out.2

One wonders what prompted Tchaikovsky, beset just then with

far closer personal problems, to choose this moment to reveal such a

long past and comparatively unimportant episode to Mme. von

Meck. The clue seems to lie in his other correspondence at that time.

She had recently arranged to settle on him a substantial annuity;

and in a letter to his brother Anatol, dated the day before he wrote

to her, he expressed his indignation on learning that Rubinstein had

called on her in an attempt to dissuade her from this course. A

mistaken idea that it would foster idleness-strongly repudiated by

Tchaikovsky a few days later in a letter to his chief-was no doubt

allied in Rubinstein's mind with the fear that it might also involve

Tchaikovsky's resignation from the faculty of the Conservatoire.

Nicholas Rubinstein had been very kind to Tchaikovsky in the past,

even to the point of giving him a room in his own house. It was in

fact he who had first enlisted Mme. von Meck's interest in

2 Translation by Rosa Newmarch.

247

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Tchaikovsky's compositions. But the two men had frequent dis-

agreements. It is understandable that Tchaikovsky should now

resent what he felt to be Rubinstein's interference in his relations

with his unknown benefactress; and his letter to her would appear to

be a bid for her sympathy.

At all events, the concerto in Bb minor was published precisely

as it stood. The first edition, comprising the orchestral parts and a

version for two pianos, though as yet no full score, was brought out

by Jurgenson in I875. That same year-on 25 October-the

concerto was given its world premiere by Hans von Bilow with the

Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by B. J. Lang. The local

critics did not care for the work. The Boston Traveller wrote: "It is

hardly destined, we think, to become classical". And the Boston

Globe dismissed it as not "an enduring work". But the composer, still

smarting from the harsh criticisms of Nicholas Rubinstein, must

have felt greatly encouraged by the glowing admiration voiced by

von Billow, who sent him an enthusiastic announcement of the

success of the performance in a cablegram believed to be the first

ever despatched from Boston to Moscow. The following month the

concerto was played in St. Petersburg by the pianist G. G. Kross

under the baton of the composer Napravnik; and in Moscow by

Tchaikovsky's pupil Sergei Taneyev, with Nicholas Rubinstein

as conductor. Rubinstein appears ultimately to have reversed his

judgment, as he himself later performed the solo part a number of

times. But the common assumption that the work is dedicated to

him is, as far as can be ascertained, incorrect-for reasons that seem

obvious, whatever may have been the composer's first thoughts on

the subject. The dedication was originally given to Sergei Taneyev;

but in the manuscript his name is scratched out and above it is

written: 'To Hans von Billow'.

Tchaikovsky's vow that he would "not alter a single note" was

not, however, destined to be fulfilled. The Boston and Russian

premieres were followed by the introduction of the concerto in

England at the Crystal Palace, under August Manns, on I I March

1876. The soloist was Edward Dannreuther, the Strasbourg-born

pianist-now chiefly remembered through his book 'Musical

Ornamentation'-who had settled in London. This occasion has a

special interest for musicians because Dannreuther, before his

performance, ventured to put before Tchaikovsky-in a letter that

has unfortunately not survived-a number of suggestions which he

thought would make the solo part more pianistic. His approach

must have been considerably more tactful than Rubinstein's, as he

received in reply a most cordial letter from the composer:

Moscow le 18/30 mars I876.

Monsieur,

J'ai resu votre bonne lettre ainsi que le programme du concert

ot vous avez bien voulu honorer de votre magnifique execution mon

248

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

oeuvre difficile et fatigante.

Vous ne sauriez croire, Monsieur, combien de joie et de plaisir

m'a cause le succ6s de cette pi6ce et vraiment je ne trouve pas les

expressions necessaires pour vous signifier ma vive reconnaissance.

Je vous remercie aussi pour les conseils tres sages et tres pratiques

que vous me donnez et soyez suir que je les suivrai des qu'il sera

question d'une deuxieme edition de mon concerto.

Je vous serre cordialement la main et me dis votre devoue et

reconnaissant

P. TSCHAIKOVSKY.8

The Musical Times, in publishing this letter, stated: "The

second and revised edition contains practically all the changes

suggested by Mr. Dannreuther". Having myself been privileged to

study for nearly five years with Edward Dannreuther, I found an

interesting corroboration of this statement through the kindness of

Admiral Hubert Dannreuther, the only surviving member of the

pianist's immediate family. He has in his home at Hastings the

actual copy of the concerto which his father used in preparing the

performance with Manns. Superimposed on that copy, a first

edition, may be seen the emendations which he suggested to

Tchaikovsky and which not only received the composer's approval

and thanks but were, as promised, incorporated in the second edition

published by Jurgenson in I879. These emendations, almost all in

the first movement, involve some I40 bars. They form a historical

document of real importance to musical scholarship. The copy

containing them is ultimately to be deposited in the British Museum.

Admiral Dannreuther must be one of the very few now living

who can claim to have actually met Tchaikovsky. He remembers

very distinctly a visit made by the composer in the late I88o's to his

father's home at 12 Orme Square, London-a house frequented by

many distinguished musicians from abroad. It is interesting that

among these was Richard Wagner, who made a lengthy stay there

in 1877 and once used the spacious music room to give a private

reading of his 'Parsifal' libretto to a select company of Dannreuther's

friends. (So great was Dannreuther's enthusiasm for Wagner that he

named four of his children after Wagnerian characters: Tristan,

Isolde, Wolfram and Siegmund; Hubert, the youngest, was named

after Hubert Parry, a close friend of Dannreuther's.) A child at the

time of Tchaikovsky's visit, Hubert was unable to follow the con-

versation, as they spoke in French. But still fresh in his memory,

even after some 80 years, is a picture of his father and Tchaikovsky

standing in the hall of the house at Orme Square as the composer

was preparing to leave. Some joke had evidently been exchanged,

for he has a particularly vivid recollection of the peals of friendly

laughter with which the two men parted.

The emendations suggested by Dannreuther proved to be not

8 This letter was published, apparently for the first time, in the Musical Times for

November I 907, with the acknowledgement that "we are indebted to Mrs. Dannreuther".

Edward Daamreuther had died in February I905.

249

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the only ones made in the concerto. Tchaikovsky, who as a young

man had expressed his dislike of piano concertos in general and

declared that he never would write one, was still haunted by Nicholas

Rubinstein's destructive criticism; and further changes were in

store. The most dramatic is concerned with the version which has

come to be accepted for the chords accompanying the famous

opening theme. These, as every student knows, cover the entire

compass of the instrument, from the lowest to the highest octave.

This treatment certainly produces a striking and glittering effect;

but it is one that was not originally intended by the composer,

whose accompaniment in the first editions was confined to

arpeggiated chords in the middle of the keyboard. Edward

Dannreuther had there contented himself with only a slight easing of

the extreme stretches asked in certain chords, but otherwise made

no change (see P1. I). The current version must therefore have been

inserted by another hand. The question is: whose ?

It is possible that Tchaikovsky himself was responsible for it. But

there is no evidence to support this. The change is not mentioned in

any extant correspondence, and no manuscript of this passage is

known to exist. Moreover, it is hard to believe that Tchaikovsky,

admittedly not an expert pianist, would have so far departed from

his original conception as to rewrite it in a manner that tempts the

soloist, as it almost invariably does, to overpower the main theme,

marked merely mezzo forte in the orchestra. The influence of some

keyboard virtuoso would seem more probable. It has been surmised

that these nineteen bars, as generally printed today and for more than

a couple of generations past, are due to the Russian pianist Alexander

Siloti, a friend of Tchaikovsky. To many people who knew Siloti

this presentation of the accompanying chords appears characteristic

of his pianism. On the other hand, we have the testimony of his

daughter Miss Kyriena Siloti, herself a professional pianist, who

has stated that she does not believe it is by her father, nor does she

know who is responsible. However, Tchaikovsky consulted Siloti

when preparing the third edition, published in I889. This is known

from a correspondence that took place between them. Again

Tchaikovsky was to put aside his vow that he would not alter a

single note. This edition introduces a change of tempo in the second

movement and a new and shorter bridge passage leading from the

polonaise-like section to the return of the second theme in the third.

And here the present version of the opening piano solo appears for

the first time.

It is a striking fact that this version is not printed in the Soviet

edition published as late as 1955 (Volume 28 of the Complete

Works of Tchaikovsky) under the supervision of A. Goldenweiser.

A feature of this edition is the printing together, one above the

other, of Tchaikovsky's original manuscript and (in slightly smaller

type) the text of the second edition, which incorporates the changes

250

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

III

(bars 124-38)

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IV

(bars 222-33)

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

suggested by Edward Dannreuther and accepted by the composer.

It is undeniable that the current, somewhat flamboyant version of

the opening piano solo has become firmly embedded in the

consciousness of the musical-as well as the non-musical-public.

There is also no denying that it is highly effective. In this form it

was conducted by Tchaikovsky during the historic opening week of

Carnegie Hall in New York in May 189I, with Adele aus der Ohe

as soloist. On the other hand, the Moscow 1955 edition appears not to

endorse its authenticity. It would no doubt be asking too much of

the present-day pianist to relinquish the undoubted appeal of this

exhilarating and athletic passage in the interest of historical scholar-

ship-though this has been done by at least one well-known artist,

the young American pianist Malcolm Frager, who has made a

careful study of the work both in the United States and in the

Soviet Union. However, a re-appraisal of our commonly accepted

text in this case would seem to be called for, with the consideration

of a treatment that restores Tchaikovsky's original balance of solo

instrument and orchestra. Meanwhile, the mystery of who was

originally responsible for this particular change appears to remain

unsolved.

251

This content downloaded from

50.30.178.13 on Sun, 27 Aug 2023 17:09:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- BeethovenDocument100 pagesBeethovengibson15089% (9)

- The Case For BrucknerDocument4 pagesThe Case For BrucknerAkiba RubinsteinNo ratings yet

- Caravan: Duke Elligton, Irvin Mills and Juan Tizol Arranged by John BerryDocument2 pagesCaravan: Duke Elligton, Irvin Mills and Juan Tizol Arranged by John BerrydirektNo ratings yet

- Conversations With Iannis Xenakis Bálint András Varga PDFDocument266 pagesConversations With Iannis Xenakis Bálint András Varga PDFJean Luc Gehrenbeck100% (2)

- Red, White, and Blue Notes: The Symbiotic Music of Nikolai KapustinDocument130 pagesRed, White, and Blue Notes: The Symbiotic Music of Nikolai Kapustinworm123_123No ratings yet

- Society RedDocument12 pagesSociety RedDaniel Espinosa100% (4)

- Schroeder - Our Schubert - His Enduring Legacy PDFDocument333 pagesSchroeder - Our Schubert - His Enduring Legacy PDFffby100% (1)

- Connoisseur of Chaos: SchnittkeDocument6 pagesConnoisseur of Chaos: SchnittkeRobert MorrisNo ratings yet

- Petty, Chopin and The Ghost of Beethoven (1999) PDFDocument19 pagesPetty, Chopin and The Ghost of Beethoven (1999) PDFunavocatNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From "Schubert's Winter Journey" by Ian Bostridge.Document14 pagesExcerpt From "Schubert's Winter Journey" by Ian Bostridge.OnPointRadioNo ratings yet

- Robert Simpson The Essence of Bruckner An EssayDocument207 pagesRobert Simpson The Essence of Bruckner An Essaykucicaucvecu100% (2)

- Schuman Violin Concerto AnalysisDocument29 pagesSchuman Violin Concerto AnalysisJNo ratings yet

- Trends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in The 21 Century: Senior High SchoolDocument20 pagesTrends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in The 21 Century: Senior High SchoolMarianne PagaduanNo ratings yet

- Radar Beacons: Racon Technical CharacteristicsDocument5 pagesRadar Beacons: Racon Technical CharacteristicshutsonianpNo ratings yet

- Schostakovich by Paul GriffithsDocument3 pagesSchostakovich by Paul Griffithstheguy8No ratings yet

- Stravinsky's Octet For Wind Instruments - KinseyDocument19 pagesStravinsky's Octet For Wind Instruments - Kinseymmmahod100% (2)

- Elliott Carter, Xenakis, Krenek, Etc. - Stravinsky, A Composers MemorialDocument182 pagesElliott Carter, Xenakis, Krenek, Etc. - Stravinsky, A Composers MemorialMario MarianiNo ratings yet

- Beethoven and C.CzernyDocument55 pagesBeethoven and C.CzernyLuis MongeNo ratings yet

- Tchaikovsky and TolstoiDocument11 pagesTchaikovsky and Tolstoijordi_f_sNo ratings yet

- Anton Bruckner Rus 005903 MBPDocument293 pagesAnton Bruckner Rus 005903 MBPpasuasafco100% (3)

- (брак) Norris Russian Piano concerto PDFDocument280 pages(брак) Norris Russian Piano concerto PDF2712760No ratings yet

- The Classical Nature of Schubert's LiederDocument12 pagesThe Classical Nature of Schubert's LiederDaniel PerezNo ratings yet

- Bilson - The Future of Schubert InterpretationDocument9 pagesBilson - The Future of Schubert InterpretationVictor CiocalteaNo ratings yet

- Stravinsky Letters To Pierre Boulez PDFDocument7 pagesStravinsky Letters To Pierre Boulez PDFAndyNo ratings yet

- Unfinished History:: A New Account of Franz Schubert's B Minor SymphonyFrom EverandUnfinished History:: A New Account of Franz Schubert's B Minor SymphonyNo ratings yet

- Hervé Lacombe, Edward Schneider - The Keys To French Opera in The Nineteenth Century (2001, University of California Press)Document432 pagesHervé Lacombe, Edward Schneider - The Keys To French Opera in The Nineteenth Century (2001, University of California Press)nen100% (1)

- The Social Life of Small Urban SpacesDocument128 pagesThe Social Life of Small Urban SpacesJavaria Ahmad93% (56)

- Cambridge University PressDocument6 pagesCambridge University PressMarco A. Gutiérrez CorderoNo ratings yet

- Czerny RecollectionsLife 1956Document18 pagesCzerny RecollectionsLife 1956Cobi AshkenaziNo ratings yet

- 4 PDFDocument7 pages4 PDFMilica MihajlovicNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 82.49.44.75 On Sun, 28 Feb 2021 19:25:30 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.49.44.75 On Sun, 28 Feb 2021 19:25:30 UTCPatrizia MandolinoNo ratings yet

- J ctt1ww3v2b 17Document12 pagesJ ctt1ww3v2b 17marisaNo ratings yet

- Trois Pièces Pour Quatuor À CordesDocument6 pagesTrois Pièces Pour Quatuor À CordesLuisNo ratings yet

- 4) Witold Lutoslawski in InterviewDocument8 pages4) Witold Lutoslawski in Interview1459626991No ratings yet

- Chronicle of A Non-Friendship - Letters of Stravinsky and KoussevitzkyDocument137 pagesChronicle of A Non-Friendship - Letters of Stravinsky and KoussevitzkyAlexandre BrasilNo ratings yet

- A Conversation With P. I. Tchaikovsky - Tchaikovsky ResearchDocument11 pagesA Conversation With P. I. Tchaikovsky - Tchaikovsky ResearchZoran RosendahlNo ratings yet

- Ovenden SchumannsFirstSymphony 1929Document2 pagesOvenden SchumannsFirstSymphony 1929Lucía Mercedes ZicosNo ratings yet

- Babitz Violin Staccato in The 18th Century 1955Document2 pagesBabitz Violin Staccato in The 18th Century 1955charles5townNo ratings yet

- 7 PDFDocument21 pages7 PDFMilica MihajlovicNo ratings yet

- Blum Minor ComposersDocument12 pagesBlum Minor ComposersKatherine QcNo ratings yet

- Arthur Schnabel 1961, Wolff Wird GenanntDocument3 pagesArthur Schnabel 1961, Wolff Wird GenanntLena NeumannNo ratings yet

- ContentServer Asp PDFDocument13 pagesContentServer Asp PDFMiguel CampinhoNo ratings yet

- ArnoldDocument13 pagesArnoldAnderson Reis100% (1)

- FanfareDocument6 pagesFanfareCarlBryanLibresIbaosNo ratings yet

- Anton Rubinstein - A Life in Music 43Document1 pageAnton Rubinstein - A Life in Music 43nunomgalmeida-1No ratings yet

- Programa de Concierto Del Pianista Arthur Rubinstein 190Document7 pagesPrograma de Concierto Del Pianista Arthur Rubinstein 190Thai AnhNo ratings yet

- Soviet Composers and The Development of Soviet Music by Stanley D Krebs New York W W Norton 1970 364 PP Dollar1150Document2 pagesSoviet Composers and The Development of Soviet Music by Stanley D Krebs New York W W Norton 1970 364 PP Dollar1150tristan 56acNo ratings yet

- Franz Liszt SonataDocument3 pagesFranz Liszt Sonatafilo89No ratings yet

- Black 1997Document9 pagesBlack 1997panshuo wangNo ratings yet

- ST Petersburg and Moscow, Autumn 2004 - by McBurneyDocument5 pagesST Petersburg and Moscow, Autumn 2004 - by McBurneymao2010No ratings yet

- 944077Document6 pages944077Felipe Merker Castellani100% (1)

- From The Writings of Schumann: Fifth Part: Dream of A Sabbath NightDocument7 pagesFrom The Writings of Schumann: Fifth Part: Dream of A Sabbath NightMichael WilhamNo ratings yet

- Eduard TubinDocument25 pagesEduard Tubinstar warsNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 82.49.19.160 On Fri, 11 Dec 2020 14:09:58 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.49.19.160 On Fri, 11 Dec 2020 14:09:58 UTCPatrizia MandolinoNo ratings yet

- Balakirev, Tchaikovsky and NationalismDocument16 pagesBalakirev, Tchaikovsky and Nationalismjordi_f_sNo ratings yet

- Marginalia Quasi Una Fantasia - On The Second Violin Sonata by A. Schnittke - D. Smirnov, G. Stockton (2002)Document10 pagesMarginalia Quasi Una Fantasia - On The Second Violin Sonata by A. Schnittke - D. Smirnov, G. Stockton (2002)vladvaideanNo ratings yet

- Cartas IAC Jeppesen ENERO 2021 275Document1 pageCartas IAC Jeppesen ENERO 2021 275Arturo Gonzalez ThomasNo ratings yet

- 1982 Folk Dances of Yugoslavia Vol VI East Serbia - Folkraft LP-54Document16 pages1982 Folk Dances of Yugoslavia Vol VI East Serbia - Folkraft LP-54benNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Folk MusicDocument3 pagesCaribbean Folk Musicdaniel watsonNo ratings yet

- Claude Debussy EssayDocument4 pagesClaude Debussy EssayMarcio CursinoNo ratings yet

- Competitive Analysis of Bridge Snack Category (Kurkure)Document46 pagesCompetitive Analysis of Bridge Snack Category (Kurkure)Tushar Sethi100% (1)

- Modified DLP 2NDDocument4 pagesModified DLP 2NDMae Sotto DavidNo ratings yet

- CZARDAS For Euphonium Sheet Music For Euphonium (Solo)Document1 pageCZARDAS For Euphonium Sheet Music For Euphonium (Solo)Rehaan EgbertNo ratings yet

- MM2 ExamDocument14 pagesMM2 ExamHarsh MalhotraNo ratings yet

- I Want To Break Free: QueenDocument6 pagesI Want To Break Free: QueenveraveraNo ratings yet

- Estudo em Si Menor (Op.35 No.22) - Fernando Sor PDFDocument3 pagesEstudo em Si Menor (Op.35 No.22) - Fernando Sor PDFJonas91jNo ratings yet

- Rastafari and Roots ReggaeDocument31 pagesRastafari and Roots ReggaeTwinomugisha Ndinyenka RobertNo ratings yet

- Kathrein 80010310v01 - Technical DocumentDocument1 pageKathrein 80010310v01 - Technical DocumentMindaugas PepperNo ratings yet

- Section 6: Protection Schemes and Diversity ArrangementsDocument21 pagesSection 6: Protection Schemes and Diversity ArrangementsAhmad Husain HijaziNo ratings yet

- 3 Levels of 1 Scale: Level 1: Parallel Motion in Unison 2 OctavesDocument2 pages3 Levels of 1 Scale: Level 1: Parallel Motion in Unison 2 OctavesPABLO MONTOYA TOBÓNNo ratings yet

- Belden Electronic Wire Catalog No 864Document28 pagesBelden Electronic Wire Catalog No 864Todorosss JjNo ratings yet

- Nsi 1000Document96 pagesNsi 1000Ganifianto RasyidNo ratings yet

- KX-TG6611FX KX-TG6612FX: Operating InstructionsDocument52 pagesKX-TG6611FX KX-TG6612FX: Operating InstructionssrlesrkiNo ratings yet

- Well. Really Slowly. Beautiful Hard Healthy English Perfectly. Incredibly Difficult Shower HourDocument1 pageWell. Really Slowly. Beautiful Hard Healthy English Perfectly. Incredibly Difficult Shower HourgianNo ratings yet

- D I S C O - Electric GuitarDocument1 pageD I S C O - Electric GuitarOleg YasinskyNo ratings yet

- Theory 4 Unit 2Document18 pagesTheory 4 Unit 2api-594920205No ratings yet

- q2 Music8 m1 Revised Copy 1Document18 pagesq2 Music8 m1 Revised Copy 1Arkein Keith AsombradoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For ATCO Common Core Content Initial Training - Part 3 - MOD 1 - ADVDocument40 pagesGuidelines For ATCO Common Core Content Initial Training - Part 3 - MOD 1 - ADVjlferreiraNo ratings yet

- Vedantam Satyanarayana Sharma: by Subiksha S 18SDMB01Document11 pagesVedantam Satyanarayana Sharma: by Subiksha S 18SDMB01Subiksha SNo ratings yet

- Adeniji Adesoye ENOCH BUSINESS PLANDocument20 pagesAdeniji Adesoye ENOCH BUSINESS PLANAdesoye AdenijiNo ratings yet