Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jamadermatology Wan 2021 Oi 210001 1623774356.72355

Jamadermatology Wan 2021 Oi 210001 1623774356.72355

Uploaded by

Meilani MelaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jamadermatology Wan 2021 Oi 210001 1623774356.72355

Jamadermatology Wan 2021 Oi 210001 1623774356.72355

Uploaded by

Meilani MelaCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Dermatology | Original Investigation

Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity

With Learning Disability in Children

Joy Wan, MD, MSCE; Nandita Mitra, PhD; Stephen R. Hooper, PhD; Ole J. Hoffstad, MA; David J. Margolis, MD, PhD

Editorial page 637

IMPORTANCE Recent population-based data indicate that atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated Related article page 667

with learning disability (LD) in children, but the association between AD severity and LD is

unknown.

OBJECTIVE To evaluate the association of AD severity with learning problems in children with

AD.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This cross-sectional study analyzed data of US

participants enrolled in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER) between November 1,

2004, and November 30, 2019. Participants were children aged 2 to 17 years at registry

enrollment with physician-confirmed diagnosis of AD and had completed 10 years of

follow-up in PEER.

EXPOSURES Atopic dermatitis severity measured by both the Patient-Oriented Eczema

Measure (POEM) score and self-report. The POEM scores ranged from 0 to 28, with strata of

clear or almost clear skin (0-2), mild (3-7), moderate (8-16), severe (17-24), and very severe

(25-28). Self-reported AD severity was categorized as clear skin or no symptoms, mild,

moderate, or severe.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Learning disability diagnosed by a health care practitioner,

as reported by the participants or their caregivers.

RESULTS Among the 2074 participants with AD (1116 girls [53.8%]; median [interquartile

range (IQR)] age, 16.1 [13.9-19.5] years at 10-year follow-up), 169 (8.2%) reported a diagnosis

of an LD. Children with an LD vs those without an LD were more likely to have worse AD

severity, as measured by the median (IQR) total POEM score (5 [1-10] vs 2 [0-6]; P < .001),

POEM severity category (moderate AD: 50 of 168 [29.8%] vs 321 of 1891 [17.0%]; severe to

very severe AD: 15 of 168 [8.9%] vs 85 of 1891 [4.5%]; P < .001); and self-report (moderate

AD: 49 of 168 [29.2%] vs 391 of 1891 [20.7%]; severe AD: 11 of 168 [6.5%] vs 64 of 1891

[3.4%]; P < .001). In multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for sex, age,

race/ethnicity, annual household income, age of AD onset, family history of AD, and comorbid

conditions, participants with mild AD (odds ratio [OR], 1.72; 95% CI, 1.11-2.67), moderate AD

(OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.32-3.30), and severe to very severe AD (OR, 3.10; 95% CI, 1.55-6.19) on

the POEM were all significantly more likely to have reported an LD than those with clear or

almost clear skin.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE This cross-sectional study found that worse AD severity was

associated with greater odds of reported LD, independent of socioeconomic characteristics,

AD onset age, and other related disorders. Although additional prospective and mechanistic

studies are needed to clarify the association of AD with learning, the findings suggest that

children with more severe AD should be screened for learning difficulties to initiate

appropriate interventions that can mitigate the consequences of an LD.

Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

Corresponding Author: Joy Wan,

MD, MSCE, Department of

Dermatology, University of

Pennsylvania Perelman School of

Medicine, 3400 Civic Center Blvd,

PCAM South Tower, 7th Floor, Office

JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(6):651-657. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0008 773, Philadelphia, PA 19104 (joywan

Published online April 14, 2021. @pennmedicine.upenn.edu).

(Reprinted) 651

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

Research Original Investigation Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity With Learning Disability in Children

G

rowing evidence indicates that atopic dermatitis (AD)

in children is associated with disruptions in sleep, at- Key Points

tention, and memory.1-3 Recent population-based data

Question What is the association of atopic dermatitis severity

in the US also demonstrate a greater prevalence of learning dis- with learning disability in children?

ability (LD) among children with AD compared with those with-

Findings In this cross-sectional study of 2074 children with

out it.4 Learning disability refers to disorders that impair areas

physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis, those with mild, moderate,

of learning, such as reading, writing, and mathematics, and is

or severe disease were significantly more likely to report a learning

associated with poor mental health, lower educational achieve- disability diagnosis by a health care practitioner compared with

ment, and worse occupational outcomes.5 those with clear or almost clear skin. Worsening severity was

Although children with AD appear more likely than chil- associated with higher rates of learning disability in a

dren without AD to have an LD diagnosis, the association of dose-dependent manner.

AD severity with LD remains unknown. Thus, the objective of Meaning Results of this study suggest that atopic dermatitis is

this study was to evaluate the association of AD severity with associated with learning problems and that children with more

learning problems in a large cohort of US children with AD. We severe skin disease should undergo screening and treatment for

hypothesized that more severe AD was associated with higher any learning difficulties.

rates of reported LD.

and a categorical variable. The POEM scores ranged from 0 to

28, with a previously established severity strata of clear or al-

most clear skin (0-2), mild (3-7), moderate (8-16), severe (17-

Methods

24), and very severe (25-28).10 In the secondary analysis, we

We used data from the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry evaluated self-reported AD severity, which was categorized as

(PEER), a prospective pediatric cohort of children with AD in the clear skin or no symptoms, mild, moderate, or severe. The study

US. This registry was designed as a postmarketing study to evalu- outcome was the diagnosis of an LD by a health care practi-

ate the risk of malignant neoplasm associated with the use of tioner, as reported by the participant or caregiver.

pimecrolimus, a topical calcineurin inhibitor for the treatment

of AD. Details of the PEER have been previously reported.6 In Statistical Analysis

brief, all participants in the PEER were aged 2 to 17 years at reg- To evaluate the association between AD severity and LD,

istry enrollment (between November 1, 2004, and November multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to

30, 2019) and had a physician-confirmed diagnosis of AD. All estimate the odds of an LD with respect to the POEM score or

participants had used pimecrolimus for at least 6 weeks in the self-reported AD severity. Analyses were adjusted for potential

6-month period preceding enrollment, although they were not confounders, including sex; age; race/ethnicity; annual house-

required to continue its use after enrollment and many did not.7 hold income; age of AD onset; family history of AD; and per-

Participants in PEER were followed up for 10 years. Written in- sonal history of asthma, seasonal allergies, sleep problems, and

formed consent was obtained from participants at the time of neuropsychiatric conditions (which included attention-deficit/

registry enrollment, and the study was granted exempt status hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], depression, anxiety, and behav-

by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board ioral or conduct problems). Because ADHD is highly prevalent

because it used existing deidentified data. and can often coincide with an LD, we also conducted a sensi-

In this cross-sectional study, we conducted an analysis of tivity analysis that excluded participants with ADHD.

participants in the PEER who had completed 10 years of fol- Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test was used to compare con-

low-up in the registry by November 30, 2019, given that data tinuous variables, and 2-tailed Fisher exact test was used to

on LD were collected in the PEER at that time. At registry en- compare categorical variables. Two-sided P < .05 indicated sta-

rollment, participants or their caregivers provided informa- tistical significance. Data analysis was performed using Stata,

tion on sociodemographic characteristics, AD history and treat- version 14 (StataCorp LLC).

ment, and personal and family medical history. At the 10-year

follow-up, participants were asked whether they had ever been

diagnosed with an LD by a health care practitioner (ie, “Has your

child ever been told by your health care provider that he/she

Results

has a learning disability?”). In addition to self-reporting their A total of 2074 participants were included in the study (Table 1).

AD severity in the preceding 6-month period, participants Of these participants, 1116 were female (53.8%) and 958 were

completed the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), male (46.2%) children. The median (interquartile range [IQR])

a validated core outcome instrument for measuring patient- age of participants was 6.0 (3.8-9.4) years at the time of ini-

reported symptoms of AD in the past week.8 Children with a tial enrollment into the PEER and was 16.1 (13.9-19.5) years at

reported diagnosis of autism were excluded from the study be- the time of their 10-year follow-up. Most participants re-

cause clinical diagnoses of LD and autism are considered mu- ported Black (931 [44.9%]) or White (818 [39.4%]) race/

tually exclusive, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical ethnicity, and most were from households with annual in-

Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition).9 comes of $0 to $49 999 (1081 [52.1%]) or $50 000 to $99 999

The exposure of interest was AD severity. In the primary (407 [19.6%]). The median (IQR) age of AD onset among par-

analysis, the POEM score was considered as both a continuous ticipants was 0.75 (0.25-2.0) years. Asthma was reported by

652 JAMA Dermatology June 2021 Volume 157, Number 6 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity With Learning Disability in Children Original Investigation Research

1008 participants (48.6%), and seasonal allergies were re-

Table 1. Participant Characteristics

ported by 1507 participants (72.7%). A family history of AD was

noted in 1093 participants (52.7%) (Table 1). Characteristic No. (%) (n = 2074)

At 10 years’ follow-up, the median (IQR) POEM score was Sex

2 (0-7), with 13 of 2074 participants (0.6%) having very se- Male 958 (46.2)

vere AD, 88 (4.2%) having severe AD, 371 (17.9%) with mod- Female 1116 (53.8)

erate AD, 506 (24.4%) with mild AD, and 1083 (52.2%) with Age, median (IQR), y 16.1 (13.9-19.5)

clear or almost clear skin. Self-reported AD severity over the Race/ethnicity

preceding 6-month period was severe for 75 participants (3.6%), White 818 (39.4)

moderate for 441 (21.3%), mild for 890 (42.9%), and clear skin Black 931 (44.9)

or none for 651 (31.4%). A total of 169 individuals (8.2%) re- Hispanic 173 (8.3)

ported an LD diagnosis. One or more of the following neuro- Asian 82 (4.0)

psychiatric conditions were reported by 482 participants Othera 70 (3.4)

(23.2%): ADHD (287 [13.8%]), anxiety (228 [11.0%]), depres- Annual household income, $

sion (156 [7.5%]), and behavioral or conduct problems (114 0-49 999 1081 (52.1)

[5.5%]) (Table 1). Sleep problems were noted in 222 partici- 50 000-99 999 407 (19.6)

pants (10.7%). ≥100 000 195 (9.4)

In univariable analyses, participants with an LD were Prefer not to answer 389 (18.8)

more likely to be male children, have Black or Hispanic race/ Age of AD onset, median (IQR), y 0.75 (0.25-2.0)

ethnicity, and have lower household income compared with Family history of AD 1093 (52.7)

those without an LD (Table 2). In addition, asthma, ADHD, de- AD severity based on the POEM score

pression, anxiety, behavioral or conduct problems, and sleep Total score, median (IQR) 2 (0-7)

problems were more common among participants with an LD Clear or almost clear skin: 0-2 1083 (52.2)

than those without an LD (Table 2). Mild: 3-7 506 (24.4)

The median (IQR) total POEM score was significantly higher Moderate: 8-16 371 (17.9)

among children with an LD compared with those without (5 Severe: 17-24 88 (4.2)

[1-10] vs 2 [0-6]; P < .001). Using severity categories based on Very severe: 25-28 13 (0.6)

the POEM score, more participants with an LD had moderate Missing 13 (0.6)

AD (50 of 168 [29.8%] vs 321 of 1891 [17.0%]) or severe to very Self-reported AD severity in past 6 mo

severe AD (15 of 168 [8.9%] vs 85 of 1891 [4.5%]) in contrast to Clear skin or none 651 (31.4)

those without an LD (Table 2). Similarly, self-reported AD Mild 890 (42.9)

severity was moderate (49 of 166 [29.5%] vs 391 of 1889 Moderate 441 (21.3)

[20.7%]) to severe (11 of 166 [6.6%] vs 64 of 1889 [3.4%]) in Severe 75 (3.6)

more children with an LD compared with those without an Missing 17 (0.8)

LD (Table 2). Asthma 1008 (48.6)

Results of unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analy- Seasonal allergies 1507 (72.7)

sis are shown in Table 3. In multivariable models, the odds of Learning disability 169 (8.2)

an LD increased by 5% per 1-point increase in the POEM score ADHD 287 (13.8)

(odds ratio [OR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02-1.08) after adjustment for Sleep problems 222 (10.7)

sex; age; race/ethnicity; household income; age of AD onset; Depression 156 (7.5)

family history of AD; and personal history of asthma, seasonal Anxiety 228 (11.0)

allergies, sleep problems, and comorbid neuropsychiatric dis- Behavioral or conduct problems 114 (5.5)

orders (Table 3). Across the POEM severity strata, children with Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity

mild AD (OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.11-2.67), moderate AD (OR, 2.09; disorder; IQR, interquartile range; POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure.

95% CI, 1.32-3.30), and severe to very severe AD (OR, 3.10; 95% a

Included Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and multiracial.

CI, 1.55-6.19) were all significantly more likely to have an LD com-

pared with children with clear or almost clear skin (Figure and

Table 3). those who reported clear or almost clear skin based on the

In secondary analyses that used self-reported AD sever- POEM score.

ity measurements, children with mild AD (OR, 1.68; 95% CI,

1.04-2.69), moderate AD (OR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.16-3.34), and se-

vere AD (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.03-5.95) also had significantly

greater odds of an LD compared with children with recently

Discussion

clear skin (Figure and Table 3). A sensitivity analysis that was To our knowledge, this analysis is one of the first studies to

limited to participants without reported ADHD yielded simi- examine the association between AD severity and learning

lar findings, with an OR for an LD of 1.64 (95% CI, 0.89-3.03) problems. The findings indicated that more severe AD was as-

for mild AD, 2.42 (95% CI, 1.28-4.55) for moderate AD, and 2.78 sociated with up to a 3-fold increase in the odds of an LD, in-

(95% CI, 1.14-6.81) for severe to very severe AD, compared with dependent of sociodemographic characteristics, AD onset age,

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology June 2021 Volume 157, Number 6 653

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

Research Original Investigation Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity With Learning Disability in Children

Table 2. Prevalence of Learning Disability by Participant and Disease Characteristics

Without learning disability With learning disability

Characteristic (n = 1903), No. (%)a (n = 169), No. (%)a P valueb

Sex

Male 862 (45.3) 96 (56.8)

.01

Female 1041 (54.7) 73 (43.2)

Age, median (IQR), y 16.1 (13.9-19.5) 16.0 (13.6-19.0) .41

Race/ethnicity

White 767 (40.3) 51 (30.2)

Black 836 (43.9) 93 (55.0)

Hispanic 149 (7.8) 24 (14.2) <.001

Asian 82 (4.3) 0 (0)

Otherc 69 (3.6) 1 (0.6)

Annual household income, $

0-49 999 966 (50.8) 113 (66.9)

50 000-99 999 381 (20.0) 26 (15.4)

<.001

≥100 000 189 (9.9) 6 (3.6)

Prefer not to answer 365 (19.2) 24 (14.2)

Age of AD onset, median (IQR), y 0.75 (0.25-2.0) 0.75 (0.25-3.0) .97

Family history of AD 993 (52.2) 99 (58.6) .13

Asthma 910 (47.9) 98 (58.0) .01

Seasonal allergies 1378 (72.5) 129 (77.3) .20

Sleep problems 164 (8.6) 58 (34.5) <.001

ADHD 194 (10.2) 93 (55.0) <.001

Depression 115 (6.1) 41 (24.3) <.001

Anxiety 185 (9.7) 43 (25.6) <.001

Behavioral or conduct problems 67 (3.6) 47 (28.0) <.001 Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis;

AD severity based on POEM score ADHD, attention-deficit/

hyperactivity disorder;

Total score, median (IQR) 2 (0-6) 5 (1-10) <.001 IQR, interquartile range;

Clear or almost clear skin: 0-2 1027 (54.3) 55 (32.7) POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema

Mild: 3-7 458 (24.2) 48 (28.6) Measure.

<.001 a

Columns may not sum to the listed

Moderate: 8-16 321 (17.0) 50 (29.8)

totals because of the missing data

Severe to very severe: 17-28 85 (4.5) 15 (8.9) for some characteristics.

Self-reported AD severity in past b

Mann-Whitney test was used for

6 mo

continuous variables and Fisher

Clear skin or none 621 (32.9) 29 (17.5) exact test was used for categorical

Mild 813 (43.0) 77 (46.4) variables.

<.001 c

Moderate 391 (20.7) 49 (29.5) Included Pacific Islander, American

Indian/Alaska Native, and

Severe 64 (3.4) 11 (6.6)

multiracial.

and other atopic and neuropsychiatric disorders. In addition, function,11 but 2 other clinic-based studies reported lower IQ in

the dose-dependent association of AD severity with LD (ie, in- children with AD and more symptoms of cognitive dysfunc-

creasingly greater odds of an LD with worsening AD severity) tion in adults with AD.3,13 Further research is thus needed to

that we observed may suggest a potential causal association in clarify the association of AD with learning and the mecha-

the reported association between AD and LD in a recent popu- nisms through which this association may be mediated. It is pos-

lation-based study of US children;4 however, causality cannot sible that symptoms of AD, such as itch and sleep impairment,

be inferred from the findings of the present study. may make learning more difficult.1,14-16 Neuroinflammatory

Existing data on the specific association between AD and signaling in the central nervous system is also implicated in nor-

learning are relatively limited to date. However, a few previ- mal memory and learning,17 and one could speculate that shared

ous studies have examined related outcomes, such as the edu- inflammatory or other pathophysiological pathways may link

cational and cognitive impact of AD. Two studies found no sta- AD and LD. In addition, more severe AD has been associated with

tistically significant association between AD and educational environmental factors, such as lower socioeconomic status, in-

attainment or between AD and school performance or stan- creased family stressors, and disadvantaged neighborhoods,

dardized test scores after adjustment for socioeconomic fac- which may increase vulnerability to cognitive or learning

tors and parental educational achievements.11,12 One of these dysfunction.18-22 Furthermore, other disorders such as ADHD,

studies also found no association between AD and cognitive anxiety, and depression, which can coincide with learning dif-

654 JAMA Dermatology June 2021 Volume 157, Number 6 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity With Learning Disability in Children Original Investigation Research

Table 3. Logistic Regression Analysis of Learning Disability by Atopic Dermatitis Severity

Adjusted models, OR (95% CI)

Unadjusted OR

Covariate (95% CI) Total POEM score POEM strata Self-reported strata

AD severity

Total POEM score, per pointa 1.06 (1.03-1.08) 1.05 (1.02-1.08) NA NA

POEM severity strata

Clear or almost clear skin 1 [Reference] NA 1 [Reference] NA

Mild 1.87 (1.30-2.69) NA 1.72 (1.11-2.67) NA

Moderate 2.59 (1.79-3.75) NA 2.09 (1.32-3.30) NA

Severe to very severe 2.98 (1.68-5.29) NA 3.10 (1.55-6.19) NA

Self-reported severity in

past 6 mo

Clear skin or none 1 [Reference] NA NA 1 [Reference]

Mild 1.84 (1.25-2.73) NA NA 1.68 (1.04-2.69)

Moderate 2.33 (1.52-3.58) NA NA 1.97 (1.16-3.34)

Severe 3.09 (1.54-6.22) NA NA 2.48 (1.03-5.95)

Sex

Male 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

Female 0.60 (0.44-0.80) 0.62 (0.43-0.89) 0.62 (0.43-0.89) 0.65 (0.45-0.93)

Age, per y 0.98 (0.94-1.02) 0.96 (0.91-1.02) 0.96 (0.91-1.02) 0.96 (0.91-1.02)

Race/ethnicity

White 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

Black 1.63 (1.17-2.26) 1.62 (1.05-2.49) 1.58 (1.02-2.44) 1.51 (0.98-2.33)

Hispanic 2.34 (1.45-3.78) 2.38 (1.33-4.24) 2.32 (1.30-4.16) 2.26 (1.26-4.04)

Otherb 0.42 (0.17-1.06) 0.13 (0.02-0.96) 0.12 (0.02-0.91) 0.13 (0.02-0.97)

Annual household income, $

0-49 999 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] Abbreviations: AD, atopic dermatitis;

NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio;

50 000-99 999 0.55 (0.37-0.84) 0.73 (0.43-1.23) 0.75 (0.45-1.27) 0.71 (0.42-1.19) POEM, Patient-Oriented Eczema

≥100 000 0.26 (0.12-0.57) 0.47 (0.19-1.17) 0.48 (0.20-1.20) 0.45 (0.18-1.11) Measure.

a

Prefer not to answer 0.58 (0.38-0.88) 0.73 (0.44-1.19) 0.74 (0.45-1.21) 0.73 (0.45-1.21) POEM severity measured as

Age of AD onset, per y 1.01 (0.96-1.06) 1.05 (0.98-1.13) 1.05 (0.98-1.13) 1.04 (0.96-1.11) continuous variable in points.

b

Included Asian, Pacific Islander,

Family history of AD 1.24 (0.93-1.67) 1.11 (0.78-1.58) 1.10 (0.77-1.57) 1.12 (0.78-1.59)

American Indian/Alaska Native, and

Asthma 1.51 (1.12-2.02) 1.17 (0.80-1.71) 1.16 (0.79-1.70) 1.16 (0.79-1.69) multiracial.

Seasonal allergies 1.39 (0.98-1.98) 0.97 (0.62-1.51) 0.98 (0.63-1.53) 0.98 (0.63-1.52) c

Included attention-deficit/

Sleep problems 5.77 (4.16-8.02) 1.96 (1.29-2.98) 1.96 (1.29-2.98) 2.08 (1.37-3.16) hyperactivity disorder, depression,

anxiety, and behavioral or conduct

Neuropsychiatric disordersc 9.41 (6.83-12.96) 6.61 (4.52-9.67) 6.54 (4.46-9.57) 6.42 (4.38-9.41)

problems.

ficulties and have been reported to be more common in indi- actually be factors on the causal pathway and thus may be me-

viduals with AD,23-25 may partially explain some of the LD ob- diators rather than confounders of the association between AD

served in individuals with AD. severity and LD. This possibility should be addressed in fu-

In this study, we adjusted for ADHD, depression, anxiety, ture studies, using analytic approaches such as mediation

and behavioral or conduct disorders as a composite variable analysis or structural equation modeling, but application of

that reflected comorbid neuropsychiatric disease, rather than these techniques in the current study was limited by the un-

as individual variables because (1) these conditions often over- certain temporality and directionality among LD and other neu-

lap, (2) the data on these conditions were provided by self- ropsychiatric or developmental disorders in the data. In addi-

report, and (3) we were primarily interested in accounting for tion, the primary objective of this study was to evaluate the

the contribution of any neuropsychiatric comorbidity in- overall association between AD severity and LD rather than to

stead of obtaining specific effect estimates for each indi- distinguish between direct and indirect outcomes mediated

vidual condition. Nevertheless, the multivariable models used by other conditions.

to analyze ADHD as a distinct variable from the composite vari- Because AD affects up to 20% of US children, with

able comprising depression, anxiety, and conduct problems did approximately one-third having moderate to severe disease,18

not meaningfully alter the findings, nor did the multivariable the impact and scope of the findings of the present study may

analyses in which ADHD, depression, anxiety, and conduct be substantial on a population level. Given that an LD has

problems were included as individual covariates. Regardless potentially lifelong implications for health, educational, and

of these different approaches, however, ADHD, mood disor- social outcomes, earlier identification (screening) and treat-

ders, and conduct problems, as well as sleep problems, may ment of at-risk children, particularly those with moderate or

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology June 2021 Volume 157, Number 6 655

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

Research Original Investigation Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity With Learning Disability in Children

survey and the participants who reported a given diagnosis of

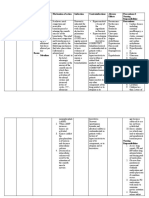

Figure. Adjusted Odds Ratios (ORs) of Learning Disability

by Severity of Atopic Dermatitis (AD)

an LD may not truly meet the criteria for a learning disorder,

future studies should incorporate formal and direct clinical

Adjusted OR Favors lower odds of Favors higher odds assessments of an LD. Nevertheless, a self-reported diagnosis

Source (95% CI) learning disability of learning disability of an LD in this study can still be taken to reflect a learning

POEM score

problem as perceived by a health care practitioner. An ADHD

Mild 1.72 (1.11-2.67)

Moderate 2.09 (1.32-3.30)

diagnosis also may be interpreted as an LD by some partici-

Severe 3.10 (1.55-6.19) pants; however, the sensitivity analysis that was limited to

Self-reported AD severity participants without ADHD showed similar associations

Mild 1.68 (1.04-2.69) between AD severity and LD. Although exposure misclassifi-

Moderate 1.97 (1.16-3.34) cation of AD severity was also possible, it was less likely

Severe 2.48 (1.03-5.95)

because a validated severity instrument, such as the POEM,

0.01 1 10 was used. Furthermore, self-reported AD severity correlated

Adjusted OR (95% CI) with the POEM severity.26

Third, given the limitations of the data in the PEER regis-

The ORs were adjusted for sex; age; race/ethnicity; annual household income;

age of AD onset; family history of AD; and comorbid asthma, seasonal allergies, try, we could not examine physicians’ assessments of AD se-

sleep problems, and neuropsychiatric disorders. The reference group was clear verity or account for other factors associated with LD, such as

or almost clear skin for both the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) parental educational achievement; these will be key areas for

score and self-reported severity. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

future scientific inquiry.

Fourth, the generalizability of the findings to all children

severe AD, are thus critical for reducing the detrimental con- with AD may be limited by the fact that participants in the PEER

sequences of AD for learning, developing appropriate inter- were required to have previously used pimecrolimus. How-

ventions, and ensuring optimal socioeducational outcomes in ever, pimecrolimus is a commonly prescribed treatment for

this patient population. mild to moderate AD. These limitations notwithstanding, the

PEER nevertheless represents a large and racially, socioeco-

Limitations nomically, and geographically diverse population of children

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional de- with physician-confirmed diagnosis of AD in the US; to our

sign of the study precluded our ability to comment on the tem- knowledge, this cohort is one of the largest pediatric AD co-

poral association between AD diagnosis or severity and LD. horts with available data on LD.

However, most participants in the PEER were diagnosed with

AD before 2 years of age, and LD is generally not diagnosed in

children until preschool age or more typically school age, thus

making it more likely that AD onset preceded LD diagnosis in

Conclusions

this cohort. Reverse causation, whereby the presence of an LD Findings of this study suggest a dose-dependent association

may have led to more severe AD at year 10 of follow-up, could between more severe AD and learning problems. Children with

not be completely excluded; however, we observed similar as- more severe AD should be screened for learning difficulties so

sociations between baseline AD severity at registry enroll- that appropriate interventions can be undertaken to mitigate

ment and LD. the consequences of an LD. Future prospective and mecha-

Second, outcome misclassification was a potential source nistic studies that use direct assessments are needed to ascer-

of bias in this study, given that LD was measured by the par- tain the timing and phenotypes of LD in children with AD and

ticipant or caregiver report of a diagnosis made by a health care to clarify the direct association of AD with LD and its poten-

practitioner. Because LD was not strictly defined in the study tial causal mechanisms.

ARTICLE INFORMATION School of Medicine, University of North Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Wan reported

Accepted for Publication: December 28, 2020. Carolina-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill (Hooper). receiving grants from Dermatology Foundation

Author Contributions: Dr Wan had full access to all during the conduct of the study and grants from

Published Online: April 14, 2021. Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dr Mitra

doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0008 of the data in the study and takes responsibility for

the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the reported receiving grants from the National

Author Affiliations: Department of Dermatology, data analysis. Institutes of Health (NIH) during the conduct of the

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Concept and design: Wan, Margolis. study. Dr Margolis reported receiving personal fees

Medicine, Philadelphia (Wan, Margolis); Section of Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: from Pfizer advisory board, personal fees from Leo

Pediatric Dermatology, Children’s Hospital of All authors. advisory board, grants from Valeant Pediatric

Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Wan); Drafting of the manuscript: Wan. Eczema Elective Registry, and grants from the NIH

Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Critical revision of the manuscript for important outside the submitted work. No other disclosures

University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of intellectual content: All authors. were reported.

Medicine, Philadelphia (Wan, Mitra, Margolis); Statistical analysis: Wan, Mitra, Hooper. Funding/Support: This study was supported in

Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Obtained funding: Wan, Margolis. part by a Career Development Award from the

Informatics, University of Pennsylvania Perelman Administrative, technical, or material support: Dermatology Foundation (Dr Wan). The data source

School of Medicine, Philadelphia (Mitra, Hoffstad, Wan, Hoffstad. used in the study, Pediatric Eczema Elective

Margolis); Department of Allied Health Sciences, Registry, was funded by a grant from Bausch

Health, formerly Valeant (Dr Margolis).

656 JAMA Dermatology June 2021 Volume 157, Number 6 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

Association of Atopic Dermatitis Severity With Learning Disability in Children Original Investigation Research

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no symptoms in clinical trials: a Harmonising Outcome 18. Silverberg JI, Simpson EL. Associations of

role in the design and conduct of the study; Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement. Br J childhood eczema severity: a US population-based

collection, management, analysis, and Dermatol. 2017;176(4):979-984. doi:10.1111/bjd.15179 study. Dermatitis. 2014;25(3):107-114. doi:10.

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or 9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic 1097/DER.0000000000000034

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 19. Chung J, Simpson EL. The socioeconomics of

the manuscript for publication. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol.

10. Charman CR, Venn AJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams 2019;122(4):360-366. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2018.12.017

REFERENCES

HC. Translating Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure 20. Hair NL, Hanson JL, Wolfe BL, Pollak SD.

1. Ramirez FD, Chen S, Langan SM, et al. (POEM) scores into clinical practice by suggesting Association of child poverty, brain development, and

Association of atopic dermatitis with sleep quality severity strata derived using anchor-based academic achievement. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):

in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(5):e190025. methods. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(6):1326-1332. 822-829. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1475

doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0025 doi:10.1111/bjd.12590 21. Mascheretti S, Andreola C, Scaini S, Sulpizio S.

2. Riis JL, Vestergaard C, Deleuran MS, Olsen M. 11. Smirnova J, von Kobyletzki LB, Lindberg M, Beyond genes: a systematic review of

Childhood atopic dermatitis and risk of attention Svensson Å, Langan SM, Montgomery S. Atopic environmental risk factors in specific reading

deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a cohort study. dermatitis, educational attainment and psychological disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;82:147-152.

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):608-610. functioning: a national cohort study. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2018.03.005

doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.027 2019;180(3):559-564. doi:10.1111/bjd.17330 22. Jeon L, Buettner CK, Hur E. Family and

3. Camfferman D, Kennedy JD, Gold M, Simpson C, 12. Ruijsbroek A, Wijga AH, Gehring U, Kerkhof M, neighborhood disadvantage, home environment,

Lushington K. Sleep and neurocognitive functioning Droomers M. School performance: a matter of and children’s school readiness. J Fam Psychol.

in children with eczema. Int J Psychophysiol. 2013; health or socio-economic background? Findings 2014;28(5):718-727. doi:10.1037/fam0000022

89(2):265-272. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.01.006 from the PIAMA birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2015; 23. Schmitt J, Romanos M, Schmitt NM, Meurer M,

4. Wan J, Shin DB, Gelfand JM. Association 10(8):e0134780. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134780 Kirch W. Atopic eczema and attention-deficit/

between atopic dermatitis and learning disability in 13. Silverberg JI, Lei D, Yousaf M, et al. Association hyperactivity disorder in a population-based

children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8): of atopic dermatitis severity with cognitive function sample of children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;

2808-2810. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2020.04.032 in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1349- 301(7):724-726. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.136

5. Stein DS, Blum NJ, Barbaresi WJ. Developmental 1359. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.041 24. Rønnstad ATM, Halling-Overgaard AS, Hamann

and behavioral disorders through the life span. 14. Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Chren MM. CR, Skov L, Egeberg A, Thyssen JP. Association of

Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):364-373. doi:10.1542/ Effects of atopic dermatitis on young American atopic dermatitis with depression, anxiety, and

peds.2011-0266 children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3): suicidal ideation in children and adults: a systematic

6. Margolis DJ, Abuabara K, Hoffstad OJ, Wan J, 607-611. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0374 review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;

Raimondo D, Bilker WB. Association between 15. Chang YS, Chou YT, Lee JH, et al. Atopic 79(3):448-456.e30. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.017

malignancy and topical use of pimecrolimus. JAMA dermatitis, melatonin, and sleep disturbance. Pediatrics. 25. Liao TC, Lien YT, Wang S, Huang SL, Chen CY.

Dermatol. 2015;151(6):594-599. doi:10.1001/ 2014;134(2):e397-e405. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0376 Comorbidity of atopic disorders with autism

jamadermatol.2014.4305 spectrum disorder and attention deficit/

16. Manchanda S, Singh H, Kaur T, Kaur G.

7. Kapoor R, Hoffstad O, Bilker W, Margolis DJ. The Low-grade neuroinflammation due to chronic sleep hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2016;171:248-255.

frequency and intensity of topical pimecrolimus deprivation results in anxiety and learning and doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.063

treatment in children with physician-confirmed memory impairments. Mol Cell Biochem. 2018;449 26. Chang J, Bilker WB, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ.

mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. (1-2):63-72. doi:10.1007/s11010-018-3343-7 Cross-sectional comparisons of patient-reported

2009;26(6):682-687. doi:10.1111/ disease control, disease severity and symptom

j.1525-1470.2009.01013.x 17. DiSabato DJ, Quan N, Godbout JP.

Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. frequency in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J

8. Spuls PI, Gerbens LAA, Simpson E, et al; HOME J Neurochem. 2016;139(suppl 2):136-153. doi:10.1111/ Dermatol. 2017;177(4):e114-e115. doi:10.1111/bjd.15403

initiative collaborators. Patient-Oriented Eczema jnc.13607

Measure (POEM), a core instrument to measure

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology June 2021 Volume 157, Number 6 657

© 2021 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 08/25/2023

You might also like

- T-Spot Test ResultsDocument1 pageT-Spot Test ResultsKamyab PirouzNo ratings yet

- 2 Substance and Non-Substance RelatedDocument238 pages2 Substance and Non-Substance RelatedAlvaro StephensNo ratings yet

- Environmental Factors Associated With Autism SpectrumDocument23 pagesEnvironmental Factors Associated With Autism SpectrumElaineBaptistaNo ratings yet

- Expressed Emotion and Eat DisordersDocument10 pagesExpressed Emotion and Eat DisordersSerbanescu BeatriceNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Central Nervous System Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours - 5th EditionDocument584 pagesCentral Nervous System Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours - 5th EditionSamira KhalilNo ratings yet

- Atopic DermatitisDocument9 pagesAtopic DermatitisJayantiNo ratings yet

- Carolina Marpaung - Maurits K. A. Van Selms - Frank LobbezooDocument8 pagesCarolina Marpaung - Maurits K. A. Van Selms - Frank LobbezooMarco Saavedra BurgosNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument5 pagesContent ServerJasmyn Cisneros QuintanaNo ratings yet

- CSS Ad-HeDocument10 pagesCSS Ad-HeFadrini SaputriNo ratings yet

- Handwriting Performance On The ETCH-M of Students in A Grade One Regular Education ProgramDocument9 pagesHandwriting Performance On The ETCH-M of Students in A Grade One Regular Education ProgramLena CoradinhoNo ratings yet

- Jamapediatrics Ramirez 2019 Oi 190001Document9 pagesJamapediatrics Ramirez 2019 Oi 190001Kiki Celiana TiffanyNo ratings yet

- Mellon2013 PDFDocument22 pagesMellon2013 PDFSipi SomOfNo ratings yet

- Association Between Atopic Dermatitis and Height, Body Mass Index, and Weight in ChildrenDocument7 pagesAssociation Between Atopic Dermatitis and Height, Body Mass Index, and Weight in ChildrenAlfi RahmatikaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Genetics of Hypodontia and Microdontia A Study of Twin FamiliesDocument6 pagesEpidemiology and Genetics of Hypodontia and Microdontia A Study of Twin FamiliesSTEFANNY MERELONo ratings yet

- Disease Trajectories in Childhood Atopic Dermatitis: An Update and Practitioner's GuideDocument12 pagesDisease Trajectories in Childhood Atopic Dermatitis: An Update and Practitioner's GuideAdhytio YasashiiNo ratings yet

- Tugas EnglishDocument3 pagesTugas EnglishRazan DhuhaNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of The Relationship Between Socioeconomic Status and Executive Function Performance Among ChildrenDocument22 pagesA Meta-Analysis of The Relationship Between Socioeconomic Status and Executive Function Performance Among ChildrenMelda DwisapitriNo ratings yet

- Musculoskeletal Low Back Pain in School-Aged Children A ReviewDocument8 pagesMusculoskeletal Low Back Pain in School-Aged Children A ReviewJOSÉ ALDER MIRANDA SALINASNo ratings yet

- Math Weaknesses in Survivors ALLDocument12 pagesMath Weaknesses in Survivors ALLPedro CampinaNo ratings yet

- Peds 2009-2789 FullDocument12 pagesPeds 2009-2789 FullAunNo ratings yet

- Nutrición Hospitalaria: Trabajo OriginalDocument7 pagesNutrición Hospitalaria: Trabajo OriginalLau PereiraNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: Christine Sattler, Pablo Toro, Peter Schönknecht, Johannes SchröderDocument6 pagesPsychiatry Research: Christine Sattler, Pablo Toro, Peter Schönknecht, Johannes SchröderMaria Jose AparicioNo ratings yet

- Determining The Prognosis of Bell's Palsy Based On Severity at Presentation and Electroneuronography (2021)Document7 pagesDetermining The Prognosis of Bell's Palsy Based On Severity at Presentation and Electroneuronography (2021)郭品榆No ratings yet

- NIH Public AccessDocument15 pagesNIH Public AccessSofía SciglianoNo ratings yet

- Trisomy 21 Research PapersDocument9 pagesTrisomy 21 Research Papersaflbmmmmy100% (1)

- Associations Between Sleep Problems, Anxiety, and Depression in Twins at 8 Years of AgeDocument10 pagesAssociations Between Sleep Problems, Anxiety, and Depression in Twins at 8 Years of AgeICU RSUNSNo ratings yet

- PIIS0923753419404079Document6 pagesPIIS0923753419404079Andi Muhammad ZulfikarNo ratings yet

- Rebbe 2018Document8 pagesRebbe 2018Karen CárcamoNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument14 pagesJournal ReadingCherryl LumentutNo ratings yet

- Polygenic Risk Scores Derived From Varying DefinitionsDocument9 pagesPolygenic Risk Scores Derived From Varying DefinitionsFelipe Neira DíazNo ratings yet

- Vaz 2011Document7 pagesVaz 2011MonicaNo ratings yet

- Sickle Cell Awareness, Prevention and Management Among Student TeachersDocument7 pagesSickle Cell Awareness, Prevention and Management Among Student TeachersAsiyatu AbubakarNo ratings yet

- Jamapediatrics Cheong 2017 Oi 160101Document7 pagesJamapediatrics Cheong 2017 Oi 160101YsagrimsNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics 2013 Dec 132 (Suppl 3) s216Document10 pagesPediatrics 2013 Dec 132 (Suppl 3) s216Carlos CuadrosNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology: Joel Marcus, PsydDocument5 pagesPsychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology: Joel Marcus, PsydIlinca RotariuNo ratings yet

- Club de Revistas 1 PDFDocument8 pagesClub de Revistas 1 PDFESTEFANIANo ratings yet

- JPaediatrNursSci 6 2 80 81Document2 pagesJPaediatrNursSci 6 2 80 81Angelo FanusanNo ratings yet

- Reading Difficulties and Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Behaviours: Evidence of An Early Association in A Nonclinical SampleDocument18 pagesReading Difficulties and Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Behaviours: Evidence of An Early Association in A Nonclinical SampleNani JuraidaNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Content Types of Early Media Exposure and Subsequent Attentional ProblemsDocument9 pagesAssociations Between Content Types of Early Media Exposure and Subsequent Attentional ProblemsMaria Laurika SimatupangNo ratings yet

- Atopic Dermatitis in Infants and Children in IndiaDocument11 pagesAtopic Dermatitis in Infants and Children in IndiaMaris JessicaNo ratings yet

- Prot 3Document8 pagesProt 3NINA EUNICE SACALANo ratings yet

- LANCET 2022 Paller Et Al Dupi in Children 6 Months To Less Than 6 YearsDocument12 pagesLANCET 2022 Paller Et Al Dupi in Children 6 Months To Less Than 6 YearsAna Cristina Felício Rios MirandaNo ratings yet

- (2007) Ar. Grigorenko - How Can Genomics InformDocument8 pages(2007) Ar. Grigorenko - How Can Genomics InformJulián A. RamírezNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Chronotype Sleep and Autism Symptom Severity in Children With ASD in COVID 19 Home Confinement PeriodDocument8 pagesThe Relationship Between Chronotype Sleep and Autism Symptom Severity in Children With ASD in COVID 19 Home Confinement PeriodAntonio GarcíaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer Monica2Document23 pagesContentServer Monica2Luis.fernando. GarciaNo ratings yet

- Personality&indiv DifferencesDocument2 pagesPersonality&indiv DifferencesJosé Antonio Aznar CasanovaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1071909120300401 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S1071909120300401 MainMónica Álvarez CórdobaNo ratings yet

- 0883073817754006Document11 pages0883073817754006Paul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Association Between Developmental Defects of Enamel and Early Childhood Caries: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesAssociation Between Developmental Defects of Enamel and Early Childhood Caries: A Cross-Sectional StudyfghdhmdkhNo ratings yet

- Allergic Rhinitis and Sleep Disorders in Children Coexistence and Reciprocal InteractionsDocument11 pagesAllergic Rhinitis and Sleep Disorders in Children Coexistence and Reciprocal InteractionsAkbar Eka PutraNo ratings yet

- Prevalensi Dan Risiko Faktor Untuk Stunting Antara Anak Sekolah Dan Remaja Di Abeokuta, Southwest NigeriaDocument10 pagesPrevalensi Dan Risiko Faktor Untuk Stunting Antara Anak Sekolah Dan Remaja Di Abeokuta, Southwest Nigeriaipan ferrelNo ratings yet

- Hamijoyo Et Al 2022 Comparison of Clinical PreDocument6 pagesHamijoyo Et Al 2022 Comparison of Clinical PreLinhNo ratings yet

- Social IsolationDocument10 pagesSocial IsolationBárbara MattosNo ratings yet

- Dyslexia Psychiatric ComorbidityDocument10 pagesDyslexia Psychiatric ComorbidityDayanandan RajarathanamNo ratings yet

- Price and Jaffee Dev Psych 2008Document28 pagesPrice and Jaffee Dev Psych 2008t0mpr1c3No ratings yet

- The Burden of Atopic Dermatitis: Summary of A Report For The National Eczema AssociationDocument5 pagesThe Burden of Atopic Dermatitis: Summary of A Report For The National Eczema AssociationIlma AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Elopement and Family ImpactDocument10 pagesElopement and Family ImpactElian Y. Sanchez-RiveraNo ratings yet

- Refractive Errors and Visual AnomaliesDocument19 pagesRefractive Errors and Visual Anomaliesfor documentNo ratings yet

- Enhancing The Parental Role in Controlling Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis A Narrative ReviewDocument13 pagesEnhancing The Parental Role in Controlling Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis A Narrative ReviewIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Sata 1Document1 pageSata 1Tasneem SeedatNo ratings yet

- ECOLOGICAL FACTORS AFFECTING CHILDHOOD OBESITY - CHAPTER 1 and CHAPTER 2Document16 pagesECOLOGICAL FACTORS AFFECTING CHILDHOOD OBESITY - CHAPTER 1 and CHAPTER 2Shenna Pitalgo TesoroNo ratings yet

- A Study Exploring The Autism AwarenessDocument8 pagesA Study Exploring The Autism AwarenessAndrés Mauricio Diaz BenitezNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology and Factors Related To The Survival of Metastatic Kidney Cancers: Retrospective Study at The Mohamed VI Center For The Cancer Treatment in Casablanca, MoroccoDocument5 pagesEpidemiology and Factors Related To The Survival of Metastatic Kidney Cancers: Retrospective Study at The Mohamed VI Center For The Cancer Treatment in Casablanca, MoroccoInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- TachyarrhythmiaDocument34 pagesTachyarrhythmiaJason FooNo ratings yet

- Rekapan Kunjungan RajalDocument96 pagesRekapan Kunjungan RajalinarutoNo ratings yet

- TB Health - ReportDocument9 pagesTB Health - Reportraheemtimo1No ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument4 pagesDrug StudyJessica GlitterNo ratings yet

- Bradley J Monk First Line Pembrolizumab ChemotherapyDocument9 pagesBradley J Monk First Line Pembrolizumab ChemotherapyRaúl DíazNo ratings yet

- FUNDA - Health & IllnessDocument3 pagesFUNDA - Health & IllnessRICVANNo ratings yet

- Principles of Radiation OncologyDocument22 pagesPrinciples of Radiation OncologyGina RNo ratings yet

- Annual Meeting Program: CollaboratingDocument330 pagesAnnual Meeting Program: CollaboratingSouhaila AkrikezNo ratings yet

- What Is Newborn ScreeningDocument2 pagesWhat Is Newborn ScreeningroksanmiNo ratings yet

- DS ICS DuaventDecilone ForteDocument6 pagesDS ICS DuaventDecilone ForteThrinNo ratings yet

- EJTCM 2019 2 2 LackaDocument9 pagesEJTCM 2019 2 2 LackaGeorgiana CrivatNo ratings yet

- Addison's Syndrome DiseaseDocument2 pagesAddison's Syndrome DiseaseNP YarebNo ratings yet

- KCCQ 12 EnglishUS 1Document2 pagesKCCQ 12 EnglishUS 1ping fan100% (1)

- HC - Assessment 2023Document4 pagesHC - Assessment 2023Bhanu Prasad SNo ratings yet

- 18 Dissociative and Sleep DisordersDocument4 pages18 Dissociative and Sleep DisordersKirstin del CarmenNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - AmoxicillinDocument2 pagesDrug Study - AmoxicillinVANESSA PAULA ALGADORNo ratings yet

- WT OetDocument13 pagesWT OetRomana PereiraNo ratings yet

- Semi Detailed Lesson Plan Eed Tle 2Document7 pagesSemi Detailed Lesson Plan Eed Tle 2Lopez Rhen DaleNo ratings yet

- Jcad 4 11 20Document2 pagesJcad 4 11 20Gabriel Balbino NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Exercise and Cardiovascular Health - A State-Of-The-Art ReviewDocument9 pagesExercise and Cardiovascular Health - A State-Of-The-Art ReviewNathan NadeauNo ratings yet

- Presentation1 FEMALE INFANTICIDEDocument10 pagesPresentation1 FEMALE INFANTICIDEShrestha Das ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Pi Ibugesic Fever and PainDocument20 pagesPi Ibugesic Fever and PainAndrew PartridgeNo ratings yet

- Dokumen - Tips - TPN PWDT FormpdfDocument22 pagesDokumen - Tips - TPN PWDT FormpdfRao SohaibNo ratings yet

- MCQ in OtologyDocument6 pagesMCQ in OtologyWael ShamyNo ratings yet

- MMW MedicationDocument2 pagesMMW MedicationammarNo ratings yet

- Clinical Chemistry Tumor MarkersDocument6 pagesClinical Chemistry Tumor Markerskatherineanne.diamanteNo ratings yet