Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guidelines For Data Collection & Analysis

Uploaded by

shyamalaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guidelines For Data Collection & Analysis

Uploaded by

shyamalaCopyright:

Available Formats

Guidelines for Data Collection & Analysis

Data Collection (See Mertler Chapter 5)

Watch Mertler’s video: https://edge.sagepub.com/mertler6e1/student-resources/chapter-5/video-resources where he

emphasizes the importance of collecting high quality and meaningful data, “as a beneficial and appropriate answer to

the research question you sought to explore in the first place”.

The context-specific, inductive, interpretive and behaviour-focused nature of action research, and the visible and active

role that the researcher takes or plays in conducting the research, render the use of qualitative data collection methods

that are narrative or language-based more appropriate than quantitative methods which rely on numbers. Qualitative

methods gather data in the form of participants' verbal or written reflections on their experiences, or as observations

made by the researcher. Analysis of these data leads to an understanding of individuals' perceptions of the phenomenon

under study.

Quantitative methods of data collection, however, can be combined with qualitative methods in action research in a

mixed-methods design. For example, you might use quantitative data in the form of students' exam results to help

establish what your intervention might be and then gather qualitative data about that intervention through interviews

and observation.

It's very important to collect rigorous and credible data that address your research question. The most common

methods of data collection used in action research are:

✔ Observations (carefully watching and systematically recording)

✔ Video recordings and photos

✔ Field notes

✔ Teacher and student journals

✔ Interviews with participants (individual and/or focus groups) and email interviews

✔ Questionnaires, descriptive surveys and rating scales

Margot Long Revised March 2023 1

✔ Checklists

✔ Formative and summative classroom assessments

✔ Existing documents and records, including participant work samples, classroom artifacts, test scores, attendance

records, and so on.

Ensuring Quality in Data Analysis

Mertler (2020, p.172) mentions that “this is probably the step during which inexperienced researchers encounter the

most anxiety”, often because of the sheer volume of narrative data that need to be coded and summarized. It’s

important that you use analytical techniques that will provide the information to answer your research question. When

you present your findings in your report, you must indicate how you arrived at them. By making your methods of

analysis transparent, the quality of your research is enhanced.

Other ways to ensure quality include:

✔ Using a wide variety of instruments, methods and sources to collect data. Triangulation or polyangulation

(Mertler 2020, p.13) - using multiple sources of data - ensures trustworthiness and consistency.

✔ Ensuring enough time is spent observing, interviewing and participating to allow for deep understanding.

✔ Member checking - involving all participants affected by the changes you make throughout the process.

✔ Ensuring the detail in the data you are collecting accurately represents your participants’ voices. This would

include negative findings.

✔ Reflexivity – interpreting your own preliminary thoughts with your actual observational notes.

✔ Consulting your critical friend / mentor to review and evaluate your processes and findings.

Analysing and Writing up Data (See Mertler Chapter 6)

One of the reassuring aspects for teachers engaging in action research using qualitative data collection methods is the

potential flexibility in the analysis of data. There are "no strict rules which have to be followed in qualitative analysis"

(Williamson & Bow in Williamson 2002, p.293). Researchers are able to select methods of analysis that are most

appropriate to organise and bring meaning to the collected data. Interpretational analysis, therefore, is a bottom-up or

inductive approach where researchers immerse themselves in their pool of data and by identifying patterns and

themes, gain understanding and create meaning.

In writing up your data analysis, write it as a narrative – as if you were telling a story, rather than using graphs or more

quantitative reporting methods. (See two examples at the end of these guidelines.) Ask, for example, “Based on the

categories I’ve made for data and the patterns I noticed, what hypothesis can be made about my findings?” Develop

general conclusions that are connected to your context and participants.

The following three steps may be useful:

Step 1: Organize your Data

Read and re-read your data and highlight anything that is relevant to your research question. As you do this, you’ll start

to get a sense of commonalities in the highlighted data. Then re-read your highlighted segments and code or categorize

them. Start with the first data bit and give it a code or descriptive phrase. Go to the next data bit - if it is similar to the

Margot Long Revised March 2023 2

previous one, give it the same code. If not, create a new code. There are lots of different ways to code, such as using

coloured highlighters, coloured sticky notes, cutting up your notes and sorting manually. Using software is also an

option.1

Continue this process until all your selected data are coded. Now, look at your codes and see if they can be grouped into

broad categories. Some categories will likely contain more data than others, and some data may fit into more than one

category – and that is all acceptable.

Step 2: Describe your Data

Begin by examining your specific observations (data). Look at key themes and experiences that stand out from your

research and focus on 4 or 5 significant findings, rather than getting side-tracked by too many other factors. For

example, you’d say, “I analyzed the data by categorizing and coding into the following strands. I further distilled this by

…, etc" Once you settle on your most important categories you need to describe the main features or characteristics. Look

for a theme that describes the data in each category.

Keep in mind that data that contradict or conflict with the patterns that have emerged must be included; you will still

learn from this info and it makes your findings more accurate and meaningful.

Step 3: Interpret and Report your Data

✔ Examine events, behaviours, observations for relationships, similarities and contradictions. Look for answers to your

question, issues that challenge your current teaching or inform future practice.

✔ Be sure to include the girls’ voices in your narrative to back up your points. For example, “I used a survey to ask the

girls how they felt about …. 15 of the 20 girls surveyed felt that the project had worked really well. Girl B noted, “I

have altered the way I approach a task like this and have realized how much more effective … it is.” The 5 girls who

did not find it useful mentioned the time factor as the main reason. Girl A stated that “it took me too long to do the

work,” and so on.

✔ Remember not to use percentages in your reporting, rather use terms like “most” or “none” or give actual numbers

like “3 of the 22 girls.”

✔ Make an effort to be impartial - don’t include your bias by using judgmental language, e.g. don’t describe findings

with terms such as “unfortunately,” “disappointing,” or “it was good to see that …”

✔ Write your report in the first person by including references to yourself where warranted, like using “I”, “my”.

✔ Include representative samples that enhance your work (quotes, excerpts from journals or daily logs).

✔ Use appendices to include data collection instruments, survey results that are summarized in the report, etc.

✔ It is quite acceptable for there to be some sort of change of direction in your research based on your analysis and

discussion of results. This would lead naturally into a further cycle of action research, and this might warrant a

mention in your reflection statement as something you’d like to pursue in the future.

1

While qualitative analysis software will help you to store and organize data, it will not do the analysis/interpretation

for you. The reality is you will not have the amount of data from your research that warrants you going this route. In

fact, doing the analysis yourself may give you richer detail, e.g. The tone of how something is said, a pause, a laugh, etc.

can all help your analysis. You can check out StatCrunch - Data analysis on the Web

Margot Long Revised March 2023 3

✔ Keep your research question top of mind as you are reporting on findings. Have you answered your research

question? What conclusions can you draw about girls and problem solving as it pertains to your research?

References

Mertler, C.A. (2020). Action Research: Improving Schools and Empowering Educators (6th Edition). New York: Sage

Publishing.

Mills, G.E. (2011). Action Research: A guide for the Teacher Researcher. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Examples of Data Collection and Analysis from Action Research Reports (These are the reports whose lit reviews were

shared previously, as well as the reference lists)

Example 1

“WE’RE A FAMILY”: USING STUDENT AGENCY TO FOSTER POSITIVE COMMUNITY IN A GRADE 7

ADVISORY GROUP

Stephen Krawec

The Allen-Stevenson School, New York, United States of America

Data Collection

Throughout my data collection period, I employed a variety of techniques to guarantee that my research was credible,

authentic, and trustworthy. A significant portion of my data derived from personal and group interviews, various

collaboration-measuring scales and indexes, questionnaires, interviews, surveys, and journal entries. Journal entries were

an important source of data because they provided boys the private and personal venue to reflect on group dynamics,

relationship growth, and their individual change as a result of the action.

Interviews provided an integral subset of the data I collected. As mentioned in Mertler (2017), truly qualitative

data interviews are best conducted following a semi structured or open-ended format (p. 134), therefore, throughout the

different phases of my action, boys were asked preplanned base questions.

Observational data was imperative to understanding the growth of positive community, as I needed to see and

hear the boys working productively, resolving arguments and debates, and making incremental progress towards their

student-created guide. Schmuck (as cited in Mertler, 2017) notes that observing students’ behavior is valuable because it

allows teachers to see things that students might not be able to report on themselves. A potential challenge, however, was

the presence of the teacher as a “data collector” and the impact this could have on student behavior. Hence, to ensure

neutrality in these circumstances, I created audio recordings of work periods and also assured the boys that my presence

would have no impact on their product and encouraged them to work and act as if I was not in the room. My final means

of data collection came in the form of participant work samples, photos, and videos.

Over the course of the project, the boys were asked to reflect on activities and lessons by filming responses to

certain questions, including “How did your contributions today impact the group?” and “How has our advisory group

changed as a result of this project?” Final one-on-one and small-group interviews were conducted at the end of the action

period, in which the boys provided general reflections on the advisory group’s change over time and the factors that

underscored the development of positive community within the group.

Data Analysis

Margot Long Revised March 2023 4

After collecting my data, I transcribed responses from interviews and dialogue and recorded structured and semi-

structured observations. I then analyzed these transcripts alongside student journal responses and survey responses. I used

data from pre-, during-, and post-action phases to track growth and change in student relationships and positive

community. In order to organize my data around major themes, I implemented Parson and Brown’s (as cited in Mertler,

2017) three-step process of organization, description, and interpretation for conducting a qualitative thematic analysis.

This analysis model provided insight into the results of the action and helped me understand the individual experiences of

the boys from the beginning of the project to its conclusion.

Discussion of Findings

The goal of my action was to introduce a rigorous, student-led group project in a non-academic advisory setting and

investigate its ability to catalyze positive community. While the project definitely helped build a positive community in

our Advisory group, several major themes emerged as a result of this project.

Agency Over the Project Cultivated Self-Assurance and Student Activism

During an unstructured observation, while the boys were planning their guide, one boy remarked, “We never get to make

decisions like this in other classes,” which prompted a wave of agreement from the other boys. I asked the boys to expand

on this idea and one responded, “Having to think for yourself and come up with ideas on our own made me realize that

we’re smarter than the adults give us credit for.” Another said, “It’s great that we get to decide and plan and execute this

project, but why won’t the school ask us to help them make decisions with school stuff, like the construction project?”

Another boy interjected, “Yeah, we actually have some really good ideas to make the new school more student-friendly.”

Considering this wave of interest from the boys, I asked them what they would do if they could start making changes to

the school, and within minutes we were immersed in a conversation about concrete aesthetic and design changes they

would make to our school, which is in the fourth year of a major construction project.

That the boys seemed interested in offering feedback and involving themselves in the construction at the school

was surprising to me considering how uninterested they had seemed beforehand. When I pressed for more information,

the boys explained to me that working on their survival guide, a project that forced them to rely on their own ideas,

processes, and decisions, had helped them develop a confidence in their own voices. One boy reflected, “In our group, we

share all the time, but no one is really ‘wrong,’ sometimes you just have to think differently about your ideas in order to

make them possible.” Another said, “When we work together and everyone is exchanging ideas and feedback we can

make things happen that wouldn’t normally be possible without everyone’s input.”

After the initial conversation, the boys, completely unprompted, had written an email to our Business Office,

proposing changes that they wanted made to our school’s furniture. The Business Office replied that the boys should

propose a budget, create a list of furniture they wanted and why, and prepare a short presentation to deliver in front of our

school’s Senior Leadership Team about the proposed changes. Reflecting on the response from the Business Office, one

boy said, “When you actually take a chance and run with an idea that you’re excited about, people listen. Speaking up and

not being too self-conscious is the hardest part.” Whereas before the project boys did not believe in the value of their

ideas, the constant exchange and validation of their ideas within the space of advisory inspired a belief in the value and

importance of their voices in larger decision-making.

Autonomy Led to a Growth in Individual Self-Awareness

Evident in the data was the assertion that reliance on the group for discussion and decision making, rather than on me or

another adult, helped boys develop a greater sense of self-awareness. By both taking stock of their own work habits and

also having to reconcile disagreements with other group members during the planning and creation phases of their project,

the boys developed a deeper understanding of themselves. Their reflections at the end of the project underscored a much

Margot Long Revised March 2023 5

more nuanced understanding of which distinct skill sets, skill deficits, attitudes and experiences each boy brought to the

group. This individual assessment demonstrated a deeper self-awareness which the boys attributed to having had

ownership over the work.

A pre-action journal response underscored the boys’ lack of self-awareness insofar that they could not understand

their individual impact on unsuccessful group work. When asked to write about past experiences involving collaboration,

one boy wrote, “Collaboration means working in a group. I hate working in a group because I end up doing all the work.”

Another boy wrote, “Collaboration is when you have to work with other people to achieve a common goal. When I know I

have to collaborate with someone else, I feel anxious because we’re probably going to disagree or someone will end up

doing more work than the other.” One can discern these boys’ lack of emphasis on self-reflection; in both comments, they

neglected to clarify their own individual impact on why past collaborative work was unsuccessful. Language such as,

“we’re probably going to disagree” or “I end up doing all the work,” instead points to fatalistic and preconceived notions

that collaboration is set up to fail.

At the end of the action, the boys returned to their initial reflections and were given the option to write a new,

updated definition for themselves. Their responses included language emphasizing a growth in self-awareness and

attributing this growth to the autonomy they were given over the project. One boy wrote, “True collaboration is when

more than one person has to work on the same task, but they don’t necessarily have to do the same thing. Both people

have to learn about their strengths to do their best on the part of the project that will help them show their abilities. In this

project, we were able to work on things that would let us shine.” Another boy’s response included, “Collaboration means

figuring out your working style first, talking about it with your teammates and then deciding together what task you can

do best…[We] learned a lot about ourselves and how each group member brings something different to the project.” This

level of reflection highlights a shift in self-awareness. Whereas early responses, rooted in negative past experiences, put

blame on others in the group or, more generally, on the notion of collaboration, the updated reflections focused on the

development of self-awareness through shared ownership over the work.

Ownership Over the Guide Strengthened Boys’ Sense of Belonging

Because one element of positive community as I defined it consisted of a “sense of belonging,” some of the pre-action

journal and survey prompts asked boys to reflect on the extent to which they felt that school valued their feelings,

contributions, and voices. Boys responded to some prompts on a Likert scale and were then asked to explain their

experiences in further detail. According to the data, 8 out of 11 boys responded “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” to the

statement, “School makes me feel like my voice matters.” Additionally, 9 out of 11 boys responded “Disagree” or

“Strongly Disagree” to the statement, “People at school (peers, teachers, or other adults) care about my thoughts, feelings,

or emotions outside of the classroom.”

In one response, a boy wrote, “The only chance we really get to talk is about class material. When things get too

personal or if someone wants to share something really deep about themselves, we don’t really get to talk about it. It

makes me feel like the teachers don’t really care about what we have to say.” Another boy echoed this sentiment, writing,

“In some classes we can express our emotions but most teachers just care about teaching the material for the tests and not

about how we feel.” We know from research conducted by Anderman (2003) and Battistich et al. (2010) that a student’s

sense of belonging and socio-emotional development is influenced significantly by his relationship with his teachers and

peers. The data suggesting that students lacked a sense of belonging in school has particular significance given the

emphasis that the boys’ responses placed on the lack of opportunities for self-expression. When we consider the latter part

of Brown’s (2015) definition of vulnerability as “emotional exposure,” boys’ emotional detachment from school makes

sense; namely, an environment that does not model and create spaces in which to practice emotional exposure cannot

expect boys to feel a strong sense of belonging.

Margot Long Revised March 2023 6

The data collected post-action suggested that a level of ownership over the work helped boys feel safer to be

vulnerable within the Advisory group, which in turn strengthened the sense of belonging they felt. In other words, when

the work started to feel authentic, so, too, did the relationships within the group. In a final journal, one boy wrote, “I

didn’t realize that others would care about what I had to say. As I got to write more about what was important to me, I felt

like I actually got to act the way I really am instead of having to be a certain type of boy at school. It’s cool because when

you are just yourself you find out that other boys are actually interested in what you have to say because it’s actually how

you feel and who you are.” Another boy wrote, “When you have control over what you want to work on, you feel like you

can be yourself because you get to share what your passions and interests are and you learn that everyone is different and

it makes you feel like there’s a place for everyone in the group.” In contrast with the pre-action responses, these

reflections suggest a strong sense of belonging with the group, in addition to a recognition of the importance of one’s

voice and its impact on the group dynamic. When the boys were given agency over the work, they, in turn, felt

empowered to be their authentic selves and it is this authenticity, willingness to lean into a place of emotional exposure,

and assurance that being your true self is something to be celebrated, that reinforced a strong sense of belonging within

the group.

Example 2

BOYS AS TEACHERS: FOSTERING SELF-EFFICACY IN YEAR 11 BOYS’ HISTORICAL SOURCE

ANALYSIS THROUGH PEER TUTORING

Luke Rawle

Toowoomba Grammar School, Queensland, Australia

Data Collection

I collected quantitative and qualitative data through a mixed-methods approach. The deliberate use of a variety of

instruments and methods to collect data aimed to polyangulate any potential findings, thus enhancing the credibility and

trustworthiness of the data, whilst also providing a rich abundance of student voices (Mertler, 2017). As such, I relied on

the following four data collection methods throughout my action research project:

· Semi-structured questionnaires

· Student self-assessment recordings (video)

· Interviews and focus groups

· Researcher observations and field notes

At the beginning of the project, I began collecting data by asking the boys to reflect upon their most recent assessment in

historical source analysis. Using Flipgrid, a video-based social learning platform, the boys recorded personal self-

assessments concerning their own ability at historical source analysis tasks. These data, in conjunction with a pre-action

questionnaire, were effective in providing a baseline for student self-efficacy before the commencement of the task, as

well as identifying specific areas of development to target with the action itself.

Student self-assessment recordings and questionnaires were also used immediately after each of the three peer tutoring

sessions to capture the boys’ reflections at critical stages of the project. The student self-assessment recordings asked the

boys to respond to the following question: “How did today’s session enhance and/or challenge my perceived ability to

succeed at historical source analysis?” Semi-structured questionnaires, using Likert scales and open-ended questions,

also provided a rich and immediate source of both qualitative and quantitative data. Based on the data collected after

Margot Long Revised March 2023 7

each session, I was able to adapt the following sessions to best target areas of perceived weakness as identified by the

boys’ responses.

I also engaged the boys in discussions about the tutoring experience, which I recorded as field notes to capture immediate

data about student behaviour. These informal conversations and unstructured observations provided valuable insight into

the boys’ experiences.

At the end of the project, I conducted a semi-structured interview with every boy. Six of these interviews were conducted

individually, with the remaining five boys interviewed as part of a focus group. The semi-structured nature of these

interviews gave me the flexibility to further explore new information conveyed by the boys (Mertler, 2017), while the

focus group provided some boys with the opportunity to collectively reflect on the experience.

Data Analysis

Once data were collected, the process of analysis began through the development of a coding scheme. This process aimed

to reduce the volume of data through the development of categories that became apparent in the narrative data (Mertler,

2017). Once coded, I made connections between the data and the research question to help establish patterns and trends

surrounding the effect the action had on boys’ self-efficacy in historical source analysis. I then used these patterns, or

emergent themes, as a means to organise the data and enable conclusions to be drawn. Being ever mindful of the process

of introspection, I attempted at all times to step back from the data to remain objective by discussing my interpretations of

the data with a critical friend.

Discussion of Results

The goal of my project was to study the extent to which acting as a tutor and teaching others would impact Year 11 boys’

self-efficacy in historical source analysis. After analysing the qualitative data, it was clear that the peer tutoring program

led to their improved self-efficacy in historical source analysis.

Upon analysis, the following four themes emerged from the data:

Peer tutoring enhanced the boys’ perceptions about their ability to complete source analysis tasks

A key theme that emerged from my analysis of the data was the boys’ enhanced confidence in responding to source

analysis questions as a result of the peer tutoring program. All of the Year 11 boys involved in the peer tutoring agreed

or strongly agreed in the post-action questionnaire that the program helped improve their ability in historical source

analysis. Boy K stated that, “the most beneficial aspect was the practice … it helped me to structure and present my

argument.” Similarly, Boy J spoke of his improved confidence in writing responses due to his greater understanding of

the requirements of the question, concluding that “it enabled me to communicate my ideas more effectively and enabled

me to solidify what I already knew.”

Understanding the specific requirements of each question also provided a framework for some boys in their written

responses. Boy E commented that “dealing with different types of questions ... helped me think about the different

structures that are required between different questions,” whilst Boy F commented that, “it helps me identify the different

types of source analysis and the slight differences in structure that are required between different questions.” On

reflection, Boy H concluded emphatically that “I definitely grew in my confidence and ability which was reflected

through my responses.”

After the action, all boys involved either agreed or strongly agreed that the program helped improve their ability in

historical source analysis (Fig. 1). For example, Boy A stated on reflection that the program “reaffirmed my own

Margot Long Revised March 2023 8

confidence in doing it myself,” whilst Boy B found that it was “definitely useful in helping me to personally improve my

source analysis work.”

Figure 1: Post-action student questionnaire responses

Peer tutoring helped boys identify their deficiencies in source analysis and self-regulate their learning

Overall, it was clear that the action enabled the majority of boys to identify and articulate deficiencies in their ability to

complete historical source analysis tasks. My analysis of the data found that eight of eleven boys suggested, through their

questionnaire responses and/or interviews, that the peer tutoring program helped in enabling them to better self-regulate

their learning. Boy D reported that the action allowed him to “gain more knowledge about yourself … and what you think

your flaws are,” whilst Boy E stated that, “It was helpful in the sense that I could actually sort of find out areas which I

definitely lacked in.”

The deficiencies identified by the boys were often personalised, providing opportunities for targeted revision to help

empower the boys through a greater understanding of their own learning experience. This was exemplified when Boy D

responded: "When you're communicating your own way of how to do it, you found out your weaknesses and your flaws,

so through that, you can just focus on how to develop your understanding on certain aspects." Moreover, reflecting after

the first peer tutoring session, Boy F stated that, "the many areas tied to reliability were hard to recall and explain, likely

as I haven't yet fully grasped the concept … so it made me understand that I need to just revise these areas once again."

Similarly, Boy H stated that it "really helped me understand how little I knew about the value of sources as a concept."

Consequently, the peer tutoring program provided the Year 11 boys with clear opportunities to reflect upon their mastery

of key concepts and skills. This enabled greater self-regulation of their own learning, which helped to develop more

confidence when responding to future tasks.

Peer tutoring enhanced boys’ ability to unpack source analysis questions

My analysis of the data demonstrated that the boys believed that their ability to unpack the exact demands of various

question types improved through the peer tutoring process. This was highlighted by nine of eleven boys indicating the

program “best helped to develop understanding different question types and unpacking the question” in the final

questionnaire.

After working with a question that required the boys to compare sources, Boy B stated that "the session helped me to

completely unpack the question and lay out all of my ideas." Boy A highlighted his improved self-efficacy through a

greater understanding of the question by stating that "going through these sessions with the younger boys, I've sort of

really slowed down and better developed my understanding of breaking down a question, knowing exactly what it wants

me to do, so I think I will be able to apply that." Boy A's improved self-regulation was obvious, making clear connections

between the skills that he was teaching and the processes he has now discovered to achieve success. In addition, Boy H

Margot Long Revised March 2023 9

noted that he would feel more comfortable in an exam situation as the program "improved your skill of just analysing the

question quickly.”

Many boys found that in-depth exposure to multiple question types increased their confidence in understanding what is

required of them in specific historical source analysis questions. Boy H highlighted that, "my skills in answering

different types of source analysis questions … [were] greatly improved by the program," whereas Boy F found that "it

forced me to understand exactly what each type of question was asking for in terms of structure and content." Similarly,

Boy J stated that the program helped in that "I definitely saw that each question had specific needs," whilst the process

helped in the development of Boy I by helping to guide "what I should find from the source."

Peer tutoring provided mastery experiences, leading to consolidation of key concepts

The Year 11 boys found that the process of tutoring younger boys in historical source analysis provided mastery

experiences to consolidate their understanding of key concepts. Throughout my analysis of the data I found comments

affirming their improved understanding of key concepts. Boy B reflected that the peer tutoring process “kind of

consolidates your understanding of it, because if you need to tell it to someone else you need to understand it first,” while

Boy G stated that, “the nature of the task as a lesson forced me to understand the concepts behind source analysis in

greater knowledge, and has significantly developed my ability and confidence to respond to unseen sources.”

The program also helped to develop a greater understanding in areas of weakness as expounded by Boy E: “It has helped

me reinforce concepts in which I wasn’t too confident in, and areas I needed to revise on.” As such, nine of eleven boys

found that the program was effective in improving their understanding of how the key concept of “perspective” can

enhance the value of a historical source. This was particularly significant as the concept was an area identified by all

boys as an area of development in the pre-action questionnaires.

It appeared that the process of tutoring younger boys encouraged many of the Year 11 boys to reflect on a deeper level

about their understanding of key concepts. Boy C stated that, “it made me think more deeply about it,” whilst Boy G

explained that “being able to teach the Year 8’s really helped my understanding of concepts on a deep level because when

I’m teaching them I have to tell myself what are constants and what are not.” Consequently, the immediate feedback

provided to the boys about their understanding of key concepts helped to self-regulate the boys’ learning, which, as Boy

K reflected, appeared to “help for revision and other tests upcoming.”

Margot Long Revised March 2023 10

You might also like

- Research Paper Data Collection MethodsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Data Collection Methodspvjxekhkf100% (1)

- Data Collection Thesis SampleDocument7 pagesData Collection Thesis Sampleqigeenzcf100% (2)

- Collection, Analyses and Interpretation of DataDocument50 pagesCollection, Analyses and Interpretation of DataJun PontiverosNo ratings yet

- Search ForDocument19 pagesSearch ForSulfadli aliNo ratings yet

- 3is Q2 Module 1.1 1Document35 pages3is Q2 Module 1.1 1yrrichtrishaNo ratings yet

- Q4-Module-1.1Document22 pagesQ4-Module-1.1PsyrosiesNo ratings yet

- Data CollectionDocument15 pagesData CollectionElena Beleska100% (1)

- Analyzing Qualitative Data MethodsDocument13 pagesAnalyzing Qualitative Data MethodsM.TalhaNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Methods - Introduction: Instructional Material For StudentsDocument23 pagesQuantitative Methods - Introduction: Instructional Material For StudentsArt IjbNo ratings yet

- III-Topic 5 Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Data Analysis Method)Document34 pagesIII-Topic 5 Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Data Analysis Method)Jemimah Corporal100% (1)

- PR2 2ndDocument28 pagesPR2 2ndjasmine fayNo ratings yet

- Home Take BR QuizDocument7 pagesHome Take BR Quizmola znbuNo ratings yet

- 3is-Q4-M1-LESSON-1.1Document48 pages3is-Q4-M1-LESSON-1.1fionaannebelledanNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Data Analysis GuideDocument6 pagesQuantitative Data Analysis GuideSaheed Lateef Ademola100% (1)

- Data Collection Section of Research PaperDocument8 pagesData Collection Section of Research Paperltccnaulg100% (1)

- RMDocument23 pagesRMSLV LEARNINGNo ratings yet

- Example Methodology Section of Research PaperDocument7 pagesExample Methodology Section of Research Papergw163ckj100% (1)

- Methods of Research: Simple, Short, And Straightforward Way Of Learning Methods Of ResearchFrom EverandMethods of Research: Simple, Short, And Straightforward Way Of Learning Methods Of ResearchRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Collect survey data and analyze qualitative responsesDocument19 pagesCollect survey data and analyze qualitative responseshareshtankNo ratings yet

- Participatory Action Research for Evidence-driven Community DevelopmentFrom EverandParticipatory Action Research for Evidence-driven Community DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- EDUM 541: Prepared By: Meriam G. TorresDocument21 pagesEDUM 541: Prepared By: Meriam G. TorresMeriam Gornez TorresNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Data Analysis GuideDocument6 pagesQuantitative Data Analysis GuideBrahim KaddafiNo ratings yet

- Steps in Writing Research MethodologyDocument5 pagesSteps in Writing Research MethodologyMerhyll Angeleen TañonNo ratings yet

- Thematic Analysis inDocument7 pagesThematic Analysis inCharmis TubilNo ratings yet

- Confidential Data 22Document12 pagesConfidential Data 22rcNo ratings yet

- Q4 Triple I Week1Document16 pagesQ4 Triple I Week1adoygrNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Data Analysis PlanDocument6 pagesDissertation Data Analysis PlanPapersWritingServiceUK100% (1)

- Data Section of Research PaperDocument8 pagesData Section of Research Paperfzhw508n100% (1)

- ObesseaDocument16 pagesObesseaDakila LikhaNo ratings yet

- Meaning, Purpose and Scope of Business ResearchDocument10 pagesMeaning, Purpose and Scope of Business ResearchRekha RawatNo ratings yet

- QM Module1Document22 pagesQM Module1Kaneki kenNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research MethodologyDocument10 pagesHow To Write A Research MethodologyAdrianaNo ratings yet

- Research Methods OverviewDocument14 pagesResearch Methods OverviewJamal BaatharNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Methodology Thesis FormatDocument8 pagesChapter 3 Methodology Thesis Formatmarypricecolumbia100% (2)

- Module 2 Developing Action Researches Steps and ActionsDocument8 pagesModule 2 Developing Action Researches Steps and ActionsDora ShaneNo ratings yet

- Business Research MethodologyDocument20 pagesBusiness Research MethodologymayankNo ratings yet

- Mco 03 em PDFDocument8 pagesMco 03 em PDFFirdosh Khan80% (5)

- Example of Data Gathering in Research PaperDocument5 pagesExample of Data Gathering in Research Papergtnntxwgf100% (1)

- WK6 Las in PR2Document4 pagesWK6 Las in PR2Jesamie Bactol SeriñoNo ratings yet

- Research Met MB 0050Document8 pagesResearch Met MB 0050Meenakshi HandaNo ratings yet

- Example of A Method Section For A Research PaperDocument9 pagesExample of A Method Section For A Research Paperqwmojqund100% (1)

- Different Types of Research Methods For DissertationDocument4 pagesDifferent Types of Research Methods For DissertationBuyingCollegePapersSingaporeNo ratings yet

- Example of Data Collection in Research PaperDocument4 pagesExample of Data Collection in Research Paperfealwtznd100% (1)

- Dissertation Unit of AnalysisDocument6 pagesDissertation Unit of AnalysisSomeoneToWriteMyPaperUK100% (1)

- Dissertation Data Collection SampleDocument6 pagesDissertation Data Collection SamplePayToWriteAPaperMilwaukee100% (1)

- How To Write The Findings Section of A Quantitative Research PaperDocument7 pagesHow To Write The Findings Section of A Quantitative Research Paperd0f1lowufam3No ratings yet

- Business Research NeoDocument35 pagesBusiness Research Neojanrei agudosNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis in ResearchDocument7 pagesData Analysis in ResearchAmna iqbal100% (1)

- REQUIRED 3 Macmillan Analysing Qualitative DataDocument23 pagesREQUIRED 3 Macmillan Analysing Qualitative DataPhan Ngọc Tuyết TrinhNo ratings yet

- 8604 Assignment No 2Document59 pages8604 Assignment No 2Njay Studio100% (2)

- KPBS12Document17 pagesKPBS12winfridamdeeNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology in Thesis SampleDocument8 pagesResearch Methodology in Thesis Samplebse4t15h100% (2)

- Quantitative Analysis Research Paper SampleDocument5 pagesQuantitative Analysis Research Paper Samplepimywinihyj3100% (3)

- RESEARCHDocument5 pagesRESEARCHPREMKUMARNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Data Collection and AnalysisDocument4 pagesDissertation Data Collection and AnalysisWhoCanWriteMyPaperAtlanta100% (1)

- PR2 Week 1Document6 pagesPR2 Week 1Argie MabagNo ratings yet

- Quantitative ResearchDocument6 pagesQuantitative Researchceedosk1No ratings yet

- Qualitative ResearchDocument9 pagesQualitative Researchsuhail iqbal sipraNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Research Methodology Dissertation ExampleDocument5 pagesQuantitative Research Methodology Dissertation ExampleWriteMyCollegePaperForMeAlbuquerqueNo ratings yet

- Inquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: Quarter 2 Module 1-Lesson 1Document14 pagesInquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: Quarter 2 Module 1-Lesson 1hellohelloworld100% (1)

- Holiday List - 2023-2024 NewDocument1 pageHoliday List - 2023-2024 NewshyamalaNo ratings yet

- 303308946-7-Classification-and-Variation-queDocument11 pages303308946-7-Classification-and-Variation-queshyamalaNo ratings yet

- exam_style_answers_P2_asal_chem_cbDocument1 pageexam_style_answers_P2_asal_chem_cbshyamalaNo ratings yet

- BillDocument2 pagesBillshyamalaNo ratings yet

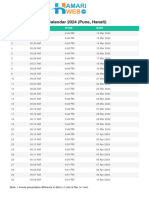

- Pune Ramadan Calendar 2024 HamariwebDocument1 pagePune Ramadan Calendar 2024 Hamariwebumarsayyed253100% (2)

- Science pre-work questions (Arun Kumar, Mar 2024)Document3 pagesScience pre-work questions (Arun Kumar, Mar 2024)shyamalaNo ratings yet

- 2023 2 Magnets and Electromagnets Checkpoint Sec 1 Progression Stage 8Document8 pages2023 2 Magnets and Electromagnets Checkpoint Sec 1 Progression Stage 8shyamalaNo ratings yet

- 9H WorkbookDocument18 pages9H WorkbookshyamalaNo ratings yet

- TENSESDocument9 pagesTENSESworld of innovationNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/31Document16 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/31shyamalaNo ratings yet

- 2022 17 Respiration and Breathing Checkpoint - Sec - 1 BiologyDocument3 pages2022 17 Respiration and Breathing Checkpoint - Sec - 1 BiologyshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/33Document8 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/33shyamalaNo ratings yet

- 2022 17 Plants Checkpoint - Sec - 1 BiologyDocument14 pages2022 17 Plants Checkpoint - Sec - 1 BiologyshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Organic DominosDocument3 pagesOrganic DominosshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument8 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/33Document8 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/33Mukmin ShukriNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument8 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelFaisal SyahrulNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Chemistry MCQDocument18 pagesGrade 11 Chemistry MCQshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Electrochemistry - CIE As Chemistry Multiple Choice Questions 2022 (Medium) - Save My ExamsDocument4 pagesElectrochemistry - CIE As Chemistry Multiple Choice Questions 2022 (Medium) - Save My ExamsshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/33Document8 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: CHEMISTRY 9701/33shyamalaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument8 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Organic DominosDocument3 pagesOrganic DominosshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Equilibria - CIE As Chemistry Multiple Choice Questions 2022 (Easy) - Save My ExamsDocument4 pagesEquilibria - CIE As Chemistry Multiple Choice Questions 2022 (Easy) - Save My ExamsshyamalaNo ratings yet

- Interior Angles Easy 3Document2 pagesInterior Angles Easy 3shyamalaNo ratings yet

- 2022 14 Measuring Speed Checkpoint - Sec - 1 Physics ProgressionDocument6 pages2022 14 Measuring Speed Checkpoint - Sec - 1 Physics ProgressionshyamalaNo ratings yet

- History of Case WorkDocument1 pageHistory of Case WorkBon FormelozaNo ratings yet

- Pedagogy, Andragogy and HeutagogyDocument16 pagesPedagogy, Andragogy and HeutagogyHosalya Devi DoraisamyNo ratings yet

- Wolfgang Keller at Konigsbrau-TAK PresentationDocument22 pagesWolfgang Keller at Konigsbrau-TAK PresentationArefeen Hridoy100% (3)

- Poverty Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesPoverty Lesson Planapi-317199957No ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and PoliticsJud DenNo ratings yet

- Lts 1 Cs Course SyllabusDocument17 pagesLts 1 Cs Course SyllabusKim ArdaisNo ratings yet

- GreenDocument4 pagesGreenFernanda MazieroNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Management - Motivating and Rewarding EmployeesDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Management - Motivating and Rewarding EmployeesDhanis ParamaguruNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan (RPP)Document7 pagesLesson Plan (RPP)Siti KomariahNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior Topics and TheoriesDocument2 pagesOrganizational Behavior Topics and TheoriesLords PorseenaNo ratings yet

- PRESENT SIMPLE - SystematizationDocument2 pagesPRESENT SIMPLE - Systematizationfederico trujilloNo ratings yet

- A Review of Grey Scale Normalization in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence For Bioinformatics Using Convolution Neural NetworksDocument7 pagesA Review of Grey Scale Normalization in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence For Bioinformatics Using Convolution Neural NetworksIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Aquinas Metaphysics CommentaryDocument6 pagesAquinas Metaphysics CommentarydiotrephesNo ratings yet

- Pragmatism: Peirce, James, Dewey and their key ideasDocument20 pagesPragmatism: Peirce, James, Dewey and their key ideasBert TrebNo ratings yet

- Decline of Communication Due To Technology in Pakistan From 2000 To 2018Document22 pagesDecline of Communication Due To Technology in Pakistan From 2000 To 2018saad anwarNo ratings yet

- AI Infrastructure 101Document8 pagesAI Infrastructure 101nicolepetrescuNo ratings yet

- Reading SkillsDocument32 pagesReading Skillsekonurcahyanto94100% (5)

- LET Reviewer for English MajorsDocument5 pagesLET Reviewer for English MajorsMichael Crisologo75% (4)

- Reference Form 2016.doc - 7Document3 pagesReference Form 2016.doc - 7Luvashen GoundenNo ratings yet

- Organisational Power and PoliticsDocument20 pagesOrganisational Power and Politicsahemad_ali10100% (1)

- What Is The Passive Voice?: Vinci. (Agent Leonardo Da Vinci)Document25 pagesWhat Is The Passive Voice?: Vinci. (Agent Leonardo Da Vinci)yuvita prasadNo ratings yet

- Conditions of PossibilityDocument1 pageConditions of PossibilityJorge Castillo-SepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- Intentions: Sadaqah and The Side Benefits Schedule: Tuesdays & Thursdays 8Pm PST - 9Pm Pst. Course Overview: 8 Chapters With Sub - PartsDocument19 pagesIntentions: Sadaqah and The Side Benefits Schedule: Tuesdays & Thursdays 8Pm PST - 9Pm Pst. Course Overview: 8 Chapters With Sub - PartsBushra AhmedNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalysis ReportDocument16 pagesPsychoanalysis ReportianneNo ratings yet

- GR12 Agri COT2 DLL - EXPLICIT - 2nd QRTRDocument3 pagesGR12 Agri COT2 DLL - EXPLICIT - 2nd QRTRgenesisaaron4No ratings yet

- Linguistics:: Different Definitions of AppliedDocument3 pagesLinguistics:: Different Definitions of AppliedMervat MekkyNo ratings yet

- Concept Analysis Usls RicaforteDocument73 pagesConcept Analysis Usls RicaforteFayne Conadera100% (2)

- Logic 1Document20 pagesLogic 1Kenneth CasuelaNo ratings yet

- Carl Jung's Analytical Psychology Theory ExplainedDocument30 pagesCarl Jung's Analytical Psychology Theory Explainedjoy ann ganadosNo ratings yet

- LP For Grand Demo Final (Direct and Indirect Speech)Document16 pagesLP For Grand Demo Final (Direct and Indirect Speech)Roxanne Cabilin100% (5)