Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Appearance of Atopic Dermatitis After Primary BCG Vaccination in A Male Infant

Uploaded by

kinzay batoolOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Appearance of Atopic Dermatitis After Primary BCG Vaccination in A Male Infant

Uploaded by

kinzay batoolCopyright:

Available Formats

Case report BCG vaccination and atopic dermatitis

The appearance of atopic dermatitis after

primary BCG vaccination in a male

infant

F. Harangi, I. Schneider and B. Sebök

SUMMARY

The case of a 22 month old male infant is reported, who underwent BCG vaccination five days after his

birth. Almost 4 months after the vaccination, an abscess developed at the site of the injection. Mildly

itching, circular to oval macular lesions appeared first surrounding the abscess, then spread over the

entire body. The rash was successfully treated with topical emollients and mometasone furoate oint-

ment. The infant displayed white dermographism, and his mother had a history of atopic dermatitis. The

possible role of underlying immunological factors are discussed in relation to the symptomatology.

K E Y Introduction Case report

WORDS Following an unremarkable pregnancy and perina-

Lymphadenitis and abscess formation in the region

of the vaccination or in the axilla occur rather frequently tal period, the currently 22 month-old infant boy un-

BCG as complications following BCG vaccination.. Rarely a derwent a BCG vaccination on his left upper arm at five

vaccination, tuberculotic infection such as lupus vulgaris or BCG os- days after his birth. Approximately four months later,

primary, teitis or sepsis occur (1,2,3,4). Recently, two children he was admitted to our department (FH) upon devel-

male infant, with atopic dermatitis (AD) have been reported in whom oping a sensitive protrusion with a diameter of 10 mm

atopic eczematous exacerbation developed after BCG revac- and eczematous skin symptoms in the vaccination area,

cination (5). as well as slightly erythematous, dry skin patches on

dermatitis the face, trunk, and extremities. The infant’s mother

The present paper reports the case of a male infant

suffering from the characteristic rashes of AD, which reported that a fluid-oozing nodule had developed on

developed primarily around an abscess at the primary the skin covering the left deltoid muscle at the site of

BCG vaccination site. the injection. Subsequently, nearly 4 months after the

Acta Dermatoven APA Vol 12, 2003, No 3 101

BCG vaccination and atopic dermatitis Case report

vaccination, an itchy focus of 40 x 50 mm in diameter,

with a red margin and crust-covered center developed.

Thereafter, she noticed additional erythematous patches

on the baby’s body.

As a child, the infant’s mother was treated for AD,

whereas its father and both siblings are healthy.

Dermatological status

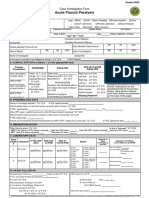

An abscess of 10 mm diameter was observed on the

left upper arm directly over the m. deltoideus. The sur-

rounding skin (40 x 25 mm) was slightly elevated and

covered with a yellowish crust. The lesion was sharply

demarcated and pruritic. Vitropression was negative.

Additionally, small red and mildly pruritic, slightly

desquamated and infiltrated patches and plaques 5 to

30 mm in diameter were observed. The irregular, sharp

margins were observed on the face, in the area above

the chin and periorally, as well as on the back and scat-

tered over the right upper and both lower limbs (Fig-

ures 1 and 2.). A white dermographism was expressed.

Laboratory tests

ESR: 5 mm/l hour; Hb: 114 g/l; Hct: 34.6%; leuko-

cytes: 17.000; thrombocytes: 322.000. Differential blood

count: segmented neutrophils 58%, lymphocytes: 30%,

monocytes: 4%, eosinophils: 8%. Serum antibodies: IgG:

7.8 g/l; IgA: 0.68 g/l; IgM: 0.49 g/l; total IgE: 100 IU/ml Figure 1. Around the scar on the left upper arm,

(normal ranges). SGOT: 32 U/l; SGPT: 26 U/l; serum a 40 x 25 mm plaque with a yellowish crust-

Fe: 7.9 µmol/l; serum Cu: 12.9 µmol/l (normal ranges). covered surface is visible

Urine bacteriology: sterile; throat flora: normal values;

bacteriological cultures from involved skin areas: E.coli.

The abscess at the vaccination site was surgically

BCG immunization, maintain that BCG is one of the

incised and excochleated. The subsequently adminis-

safest and most effective vaccinations available (10).

tered repeated dressings with polyvidon-iodine oint-

In the case of the infant presented, an abscess de-

ment resulted in a fast drying and epithelization. The

veloped at the primary BCG vaccination site, and AD

skin signs distributed widely over the body were inter-

symptoms (beginning around the abscess) were ob-

preted as AD, therefore emollients in addition to

served later. The question arises whether this was a ca-

momethason furoate (once daily) were initiated. A

sual association or indeed a causal connection between

gradual improvement followed, and two weeks later

BCG vaccination and development of AD in an infant

the patient was entirely asymptomatic. No symptoms

with a positive family history (mother). Data concern-

or complaints were present at the follow-up examina-

ing this question are scant and contradictory. A recent

tions at two weeks, two months, and one year. In the

study reported the recurrence of AD following BCG

BCG vaccination area, a pea-sized scar (fibrous nod-

revaccination (5). Japanese authors claim that early BCG

ule) was palpable.

vaccination can prevent atopic diseases (11), while a

Swedish retrospective study carried out in a large popu-

lation suggests that early vaccination does not influence

Discussion the onset of atopic disease in the pre-school period (12).

BCG vaccine usually induces an Th1 immune re-

BCG vaccination can lead to several complications, sponse, whereas atopic dermatitis is associated with Th2

of which lupus vulgaris (1,2,3,4,5,6), disseminated BCG lymphocytic infiltration. AD can be regarded as a chronic

infection in conjunction with hyper-IgE syndrome (7), skin disease with an increased IL-4/IFN-γ ratio medi-

and osteomyelitis (8) are mentioned in the literature. ated by cutaneous lymphocyte associated antigen

Upon reporting complications related to BCG vaccina- (CLA+) Th2 lymphocytes (13,14). Among other activi-

tion, some authors question its harmlessness (9). Oth- ties, Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10, thereby

ers, describing lupus vulgaris following intracutaneous stimulating the formation of B-cells, as well as the ac-

102 Acta Dermatoven APA Vol 12, 2003, No 3

Case report BCG vaccination and atopic dermatitis

family history!) relatively increased IL-4 production and

in consequence the enhanced Th2 cell generation (un-

like the usual Th1 immune response following BCG

vaccination) can be postulated as a possible cause for

the development of atopic skin symptoms. A similar

mechanism is suggested by Dalton et al., upon observ-

ing the flare-up of atopic skin symptoms following BCG

revaccination in two children suffering from AD (5).

Another possible mechanism may be seen in the so-

called "Toll-like" receptors (TLR) found on the surface

of immune as well as on endothelial cells. These recep-

tors are capable of recognizing bacterial lipopolysac-

charides and, similarly to the primary cytokine (IL-1,

*TNF-α) receptors, employ the intracellular signaling

system with the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) to trigger the

transcription of genes for E-selectin (the endothelial

ligand of CLA), cytokines, chemokines and adhesive

molecules leading to cutaneous inflammation (17,18).

Under the influence of mycobacterial cellular wall com-

ponents, a subtype of TLR induces TNF-α production,

which, following the previously described mechanism,

may lead to inflammatory skin phenomena (19).

It is known that AD has two variants, the so-called

extrinsic and intrinsic type (20). In the former, specific

IgE can be detected and antiallergic therapy is effec-

Figure 2. On the face, the right upper arm, the tive. The intrinsic form can be characterized, by normal

back, and the lower extremities, disseminated serum IgE levels, eosinophilia, negative immediate type

macules and papules with various diameters skin tests, low tissue-localized IL-5 and IL-13 expres-

are present. The exanthemas were sion, and normal serum IL-5 levels (21).

characterized by itching, reddish color, and fine On the basis of the normal serum IgE level and the

scales. moderate eosinophilia in our patient, the intrinsic form

of AD has to be considered. The so called id-reaction is

however also a diagnostic possibility. It may be assumed

cumulation of eosinophils and mastocytes in the skin. that BCG acts as a superantigen (SAG), causing CLA

Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine triggers an Th1 expression in T-cells, and in consequence, so-called skin

type of immune reaction in adults and the primary vac- homing of these cells (5).

cination induces a similar Th1 type memory-cell re- Based on these theoretical considerations, a con-

sponse in newborns (15). In the differentiation of the nection of causality between BCG vaccination and the

activated naive Th cells, the IL-12/IL-4 ratio plays a key appearance of AD symptoms may be a possibility in

role. If the relative amount of IL-4 increases, the differ- our patient. Renewed appearance of AD phenomena

entiation of Th2 cells will have prevalence (16). following revaccination would give substance to these

In our patient, the genetically determined (positive speculations.

REFERENCES

1. Lomholt S: Lupus vulgaris developed in the reaction to a Calmette vaccination Acta Tuberc Scand

1946; 20:136.

2. Davis SD: Lupus vulgaris after vaccination with BCG. Tubercle 1995; 36:179-81.

3. Fischer E: Lupus vulgaris in loco nach BCG-Impfung. Dermatologica 1957; 114: 290-1.

4. Schneider I, Várszegi D, Harangi F: Lupus vulgaris as a rare complication of BCG vaccination. Eur J

Dermatol. 1994; 4: 335-6.

5. Dalton SJ, Haeney MR, Patel L, David TJ: Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis after bacillus Calmette-

Guerin vaccination. JRS Medicine 1998; 91:133-4.

Acta Dermatoven APA Vol 12, 2003, No 3 103

BCG vaccination and atopic dermatitis Case report

6. Izumi AK, Matsunaga J: BCG vaccine induced lupus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol 1982;118; 171-2.

7. Pasic S, Lilic D, Pejnovic N, Vojvodic D, Simic R, Abinun M: Disseminated Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

infection in a girl with hyperimmunglobulin E syndrome. Acta Paediatr 1998; 87: 702-4.

8. Lin CJ, Yang WS, Yan JJ: Mycobacterium bovis osteomyelitis as a complication of Bacillus Calmette-

Guerin (BCG) vaccination. J Bone-Joint Surg Am 1999; 81:1305-11.

9. Karnak I, Senocak ME, Buyukpamukcu N, Gocmen A: Is BCG vaccine innocent? Paediatr Surg Int?

1997; 12: 220-3.

10. Vittori F, Groslafeige C: Le lupus tuberculeux post-BCG. Une complication rare de la vaccination.

Arch. Paediatr. 1996; 3: 457-9.

11. Yoneyama H, Suzuki M, Fujii K, Osayima Y: The effect of DPT and BCG vaccinations on atopic disor-

ders (Jpn) Arerugi 2000; 49: 585-92.

12. AIm JS, Lilja G, Pershagen G, Scheynius A: Early BCG vaccination and development of atopy. Lancet

1997; 350: 400-13.

13. Hamid Q, Boguniewicz M, Leung DYM: Differential in situ cytokine gene expression in acute versus

chronic atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest 1994; 94: 870-6.

14. Virtanen T, Maggi B, Manetti R et al: No relationship between skin infiltrating Th2-like cells and

allergen-specific IgE response in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995; 96: 411-20.

15. Marchant A, Goetghebuer T, Ota MO et al: Newborns develop a Th1 type immune response to Myco-

bacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination. J.Immunol1999; 163: 2249-55.

16. Schuler G: Grundlagen der Immunologie und Allergologie. In: Fritsch P: Dermatologie und

Venerologie. Lebrbuch und Atlas. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York Springer Verlag 1998: 43-53.

17. Robert C, Kupper TS: Inflammatory skin diseases, T cells and immune surveillance. N Engl J Med

1999; 341: 1807-28.

18. Barnes PJ, Karin M: Nuclear factor κB pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases.

N Engl J Med 1977; 336: 1066-77

19. Brightbill HD, Librati DH, Krutzik SR et al.: Host defense mechanisms triggered by microbial lipo-

proteins through toll-like receptors. Science 1999; 285: 732-6.

20. Wûthrich B: Neurodermitis atopica sive constitutionalis. Ein pathogenetisches Modell aus der Sicht

des Allergologen. Akt Dermatol 1983; 9: 1-7.

21. Akdis CA, Akdis M, Simon N et al: T cells and T cell derived cytokines as pathogenetic factors in the

nonallergic form of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 1999; 113: 628-44.

A U T H O R S ' Ferenc Harangi MD, County Childrens’ Hospital, Pecs, Hungary

A D D R E S S E S Imre Schneider MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, Dept Dermatology,

Medical Faculty , H-7624 Pecs, Kodaly Z. utca 20, Hungary.

E-mail: schneid@derma.pote.hu

Bela Sebök MD, Dorozsnai & Co.Ltd. Dermatology Section, Pecs

104 Acta Dermatoven APA Vol 12, 2003, No 3

You might also like

- SOP - SDF For Regional Tourists - V13 (Approved by The Cabinet)Document6 pagesSOP - SDF For Regional Tourists - V13 (Approved by The Cabinet)Tenzin TsheltrimNo ratings yet

- AEC Catalogo ENGDocument52 pagesAEC Catalogo ENGAlexandru OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Karla DesiertoDocument147 pagesKarla DesiertoMarco AlejandreNo ratings yet

- FASH235 Document 2Document2 pagesFASH235 Document 2siibnuNo ratings yet

- A Review Paper On Textile Fiber IdentificationDocument11 pagesA Review Paper On Textile Fiber IdentificationMD.MAHABUB ALOM REFAETNo ratings yet

- NOTES CD Lecture Generic 2022Document182 pagesNOTES CD Lecture Generic 2022Meryville JacildoNo ratings yet

- Headsets Volume 1 Issue 10Document16 pagesHeadsets Volume 1 Issue 10JUAN GONZALEZNo ratings yet

- Ahmad Basori VidiDocument30 pagesAhmad Basori VidiIka AyuNo ratings yet

- Ecpg OrlapDocument258 pagesEcpg OrlapNoha Ibraheem HelmyNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Development of Multiple Phase Shift Modulation in A Dual Active BridgeDocument250 pagesAnalysis and Development of Multiple Phase Shift Modulation in A Dual Active BridgeAdam RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Catalogue Brand Book 2022Document32 pagesCatalogue Brand Book 2022Rifqi Athallah (Mickey James)No ratings yet

- Account Statement 102245699Document3 pagesAccount Statement 102245699Ankit ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Pgi 2020Document50 pagesPgi 2020ShishirNo ratings yet

- Review TestDocument8 pagesReview TestнуркызNo ratings yet

- Tenth GradeDocument13 pagesTenth GradeNahum VásquezNo ratings yet

- 11 Wyciszkiewicz Golacki Samociuk Hazards 150-164Document15 pages11 Wyciszkiewicz Golacki Samociuk Hazards 150-164JacekNo ratings yet

- Implementation of Green Tourism Concept On Glamping Tourism in BaliDocument5 pagesImplementation of Green Tourism Concept On Glamping Tourism in BaliAlex AbelNo ratings yet

- Persepsi Pengelola Hotel Bintang 1-5 Terhadap Fungsi Dan Fitur Media Pemasaran Online Di Kecamatan Kuta, Provinsi BaliDocument16 pagesPersepsi Pengelola Hotel Bintang 1-5 Terhadap Fungsi Dan Fitur Media Pemasaran Online Di Kecamatan Kuta, Provinsi Baliachmad syahrul tawakalNo ratings yet

- OxyContin, Prescription Opioid Abuse and Economic MedicalizationDocument14 pagesOxyContin, Prescription Opioid Abuse and Economic MedicalizationCharlotte AgliataNo ratings yet

- Full Active Pipeline Protocol v5.05Document33 pagesFull Active Pipeline Protocol v5.05lamlart0619No ratings yet

- Karim 2020Document15 pagesKarim 2020Astri SuyataNo ratings yet

- Online Grocery ShopDocument6 pagesOnline Grocery ShopIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- HSBC Mpower Platinum Credit CardDocument9 pagesHSBC Mpower Platinum Credit Cardjialiang leeNo ratings yet

- Mahagenco Recruitment 2023 For 34 JR Officer PostsDocument10 pagesMahagenco Recruitment 2023 For 34 JR Officer PostsGanesh DaphaleNo ratings yet

- 3 0 MCQ 6-10Document6 pages3 0 MCQ 6-10Winnie NgNo ratings yet

- C1 Listening 4 PDFDocument1 pageC1 Listening 4 PDFAnalia De LEon100% (1)

- GSC3610 QigDocument25 pagesGSC3610 QigRishab SharmaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Mobile Communication Network Performance: January 2016Document13 pagesEvaluation of Mobile Communication Network Performance: January 2016Lalita LakraNo ratings yet

- Abces Thyroidien Fistulise Revelant Un Carcinome oDocument14 pagesAbces Thyroidien Fistulise Revelant Un Carcinome oZouol RodrigueNo ratings yet

- Genetic Diversity in Farm Animals-A Review-Groeneveld2010Document26 pagesGenetic Diversity in Farm Animals-A Review-Groeneveld2010Raul alejandro Kim gomezNo ratings yet

- Ret Chhattisgarh 10 11Document29 pagesRet Chhattisgarh 10 11Dinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Particle Velocity and Deposition EfficiencyDocument29 pagesParticle Velocity and Deposition Efficiencybat sohNo ratings yet

- Cvitanovic PotresDocument9 pagesCvitanovic PotresHrvoje CvitanovicNo ratings yet

- (1-14) Study On Individual's Preference About Online Cab Booking ServicesDocument14 pages(1-14) Study On Individual's Preference About Online Cab Booking ServicesKartik RajputNo ratings yet

- Daily Current Affairs: 03 June 2022Document20 pagesDaily Current Affairs: 03 June 2022Shirish sableNo ratings yet

- 5 154 1Document22 pages5 154 1Econometric AnalysisNo ratings yet

- TINT BrochureDocument24 pagesTINT BrochureFood RestorersNo ratings yet

- Eaton Emergency Lighting SC Exit - Safety Zeta4 Apr2018 DatasheetDocument4 pagesEaton Emergency Lighting SC Exit - Safety Zeta4 Apr2018 DatasheetShahzil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Notice NC LTDocument170 pagesNotice NC LTPranabh KumarNo ratings yet

- Latest Current Affairs 13 October-2022Document8 pagesLatest Current Affairs 13 October-2022Debashish BiswasNo ratings yet

- 178imguf EngineeringDocument20 pages178imguf EngineeringSANJEET KUMARNo ratings yet

- Falaknuma Exp Third Ac (3A)Document2 pagesFalaknuma Exp Third Ac (3A)Abhaya Kumar NayakNo ratings yet

- Logiq c5 BrochureDocument2 pagesLogiq c5 BrochureFabio PappalardoNo ratings yet

- BioplasticDocument2 pagesBioplasticReymundo Pantonial Tugbong JrNo ratings yet

- Manitoba - AssessmentsDocument30 pagesManitoba - AssessmentsMharvinn CoolNo ratings yet

- United States Patent: (10) Patent No .: US 10, 278, 244 B1Document45 pagesUnited States Patent: (10) Patent No .: US 10, 278, 244 B1Roberto AbregoNo ratings yet

- Iot Smart Plant Monitoring, Watering and Security System: 1 AbstractDocument11 pagesIot Smart Plant Monitoring, Watering and Security System: 1 AbstractNithinNo ratings yet

- Account - Statement - 011022 - 311022Document17 pagesAccount - Statement - 011022 - 311022Anjani DeviNo ratings yet

- Whizlabs AWS-SAP-01-Practice Test2Document3 pagesWhizlabs AWS-SAP-01-Practice Test2asrbusNo ratings yet

- MAG 230 BrochureDocument38 pagesMAG 230 BrochureZakaria Ghrissi alouiNo ratings yet

- Plateau State Polytechnic Barkin Ladi: Offer of Provisional Admission For 20 21/2022 Academic Session (Morning/Evening)Document1 pagePlateau State Polytechnic Barkin Ladi: Offer of Provisional Admission For 20 21/2022 Academic Session (Morning/Evening)Jonathan kataikoNo ratings yet

- History: Important DaysDocument3 pagesHistory: Important DaysVARATHAPANDIAN GNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Decision WP 1049Document32 pagesSupreme Court Decision WP 1049HS100% (1)

- OLIN - Curing Agent Easy-Fit ADocument9 pagesOLIN - Curing Agent Easy-Fit ABoyet BaldeNo ratings yet

- Mycotoxins: Factors Influencing Production and Control StrategiesDocument32 pagesMycotoxins: Factors Influencing Production and Control StrategiesMarcio SitoeNo ratings yet

- Document 1312021 53807 AM ZrAxTn7pDocument8 pagesDocument 1312021 53807 AM ZrAxTn7pGisselle RodriguezNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledprashant negiNo ratings yet

- Edukasi Terapi Rendam Kaki Dengan Garam Dan Aromaterapi Di PMB Muzilatul Nisma Kota JambiDocument7 pagesEdukasi Terapi Rendam Kaki Dengan Garam Dan Aromaterapi Di PMB Muzilatul Nisma Kota JambiPaulina IkaNo ratings yet

- Intern Final Draft AshishDocument40 pagesIntern Final Draft AshishMadhav RajbanshiNo ratings yet

- Comment: Bcg-Induced Trained Immunity: Can It Offer Protection Against Covid-19?Document3 pagesComment: Bcg-Induced Trained Immunity: Can It Offer Protection Against Covid-19?edison aruquipaNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument15 pagesAssignmentkinzay batoolNo ratings yet

- Myocardial InfarctionDocument11 pagesMyocardial Infarctionkinzay batoolNo ratings yet

- Infra Red SpecrtosDocument12 pagesInfra Red Specrtoskinzay batoolNo ratings yet

- MyristicaDocument6 pagesMyristicakinzay batoolNo ratings yet

- Toxicity of Glycosides-1-1Document9 pagesToxicity of Glycosides-1-1kinzay batoolNo ratings yet

- Mode of Infection of DiseaseDocument14 pagesMode of Infection of Diseasekhalid100% (1)

- National Dental College and Hospital: Seminar On ImmunityDocument24 pagesNational Dental College and Hospital: Seminar On Immunitydr parveen bathlaNo ratings yet

- Viral Hepatitis Types Symptoms TreatmentDocument9 pagesViral Hepatitis Types Symptoms TreatmentTAMBI TANYINo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Practice of Allergen Immunotherapy in India: 2017-An UpdateDocument31 pagesGuidelines For Practice of Allergen Immunotherapy in India: 2017-An UpdateKrishna Bharadwaj ReddyNo ratings yet

- Aso Latex Spin ReactDocument1 pageAso Latex Spin ReactLuis Ferdinand Dacera-Gabronino Gamponia-NonanNo ratings yet

- 1353 FullDocument15 pages1353 FullmilsaNo ratings yet

- Abses Hepar: Erina Angelia Perceptor: DR - Lukas.,Sp - PDDocument12 pagesAbses Hepar: Erina Angelia Perceptor: DR - Lukas.,Sp - PDSimon Messi SiringoringoNo ratings yet

- Blood Groups Assignment AaaDocument3 pagesBlood Groups Assignment AaaLoro JDNo ratings yet

- Novilyn C. Pataray BSN - Ii Pharyngitis: St. Paul College of Ilocos SurDocument1 pageNovilyn C. Pataray BSN - Ii Pharyngitis: St. Paul College of Ilocos SurCharina AubreyNo ratings yet

- VasculittisDocument28 pagesVasculittisBernamai CalamNo ratings yet

- Seronegative Rheumatoid Arthritis: One Year in Review 2023Document11 pagesSeronegative Rheumatoid Arthritis: One Year in Review 2023drcristianogalhardiNo ratings yet

- Drug Study: NCM 106 PharmacologyDocument2 pagesDrug Study: NCM 106 Pharmacologypoleene de leon100% (1)

- Prometric Notes3Document133 pagesPrometric Notes3Majid KhanNo ratings yet

- Fever With Rash Atlas PDFDocument14 pagesFever With Rash Atlas PDFK C Goutham ReddyNo ratings yet

- Cif AfpDocument2 pagesCif Afpninzah wanzahNo ratings yet

- 7.01-Medically Important Bacteria II (Part I)Document54 pages7.01-Medically Important Bacteria II (Part I)danNo ratings yet

- Vaccination in SwineDocument6 pagesVaccination in SwineAljolynParungaoNo ratings yet

- PsoriasisDocument57 pagesPsoriasisapi-19916399100% (1)

- This Chapters 1 5Document29 pagesThis Chapters 1 5Joanna Marie EstanislaoNo ratings yet

- Polio DR Suzanne Humphries Clear SlidesDocument57 pagesPolio DR Suzanne Humphries Clear Slidesvaccinationcouncil100% (21)

- The Statistics of Lyme in The State From Louisiana From The DHHDocument5 pagesThe Statistics of Lyme in The State From Louisiana From The DHHSam WinstromNo ratings yet

- Dr. Hilario D. G. Lara, M.D. (Public Health) : The Pioneer of Modern Public Health in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesDr. Hilario D. G. Lara, M.D. (Public Health) : The Pioneer of Modern Public Health in The PhilippinesLexter CrudaNo ratings yet

- Meningitis PDFDocument8 pagesMeningitis PDFrizeviNo ratings yet

- Multi Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDocument40 pagesMulti Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDr. Jayesh PatidarNo ratings yet

- Transmission Based PrecautionsDocument8 pagesTransmission Based Precautionsniraj_sd100% (1)

- What Is SalmonellaDocument4 pagesWhat Is SalmonellaRosNo ratings yet

- ATLS-9e Tetanus PDFDocument2 pagesATLS-9e Tetanus PDFAroell KriboNo ratings yet

- Acute Pancreatitis PresentationDocument24 pagesAcute Pancreatitis PresentationhtmgNo ratings yet

- DHIS PHC Facility Monthly Report FormDocument4 pagesDHIS PHC Facility Monthly Report FormUmair SaleemNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 Summative TestDocument4 pagesGrade 10 Summative TestJaymar B. MagtibayNo ratings yet

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (27)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeFrom EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (253)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (59)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)