Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Trinh Cong Son Phenomenon

Uploaded by

Nguyễn AnCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Trinh Cong Son Phenomenon

Uploaded by

Nguyễn AnCopyright:

Available Formats

The Tri̇nh Công Son Phenomenon

Author(s): John C. Schafer

Source: The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 66, No. 3 (Aug., 2007), pp. 597-643

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20203200 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 22:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The JournalofAsian StudiesVol. 66, No. 3 (August)2007: 597-643.

? 2007 Association of Asian Studies Inc. doi: 10.1017/S0021911807000915

The Trinh Cong San Phenomenon

JOHN C. SCH?FER

This article attempts to explain the extraordinary popularity ofVietnamese com

poser and singer Trinh Cong Son. Although he attracted attention with love

songs composed in the late 1950s, itwas his antiwar songs, particularly those

collected in Songs of Golden Skin (1966), that created the "Trinh Cong Scm

were banned

phenomenon." Though these songs by the Saigon government,

in the South the war. was distrusted

they circulated widely during Though he

the new Communist government the war, Scm continued to compose

by after

until his death in 2001, and his songs are still popular in Vietnam today.

Some reasons for his popularity are offered, including the freshness of his

early love songs, his evocation of Buddhist themes, his ability to express the

mood of Southerners during thewar, and a mixture of patience and persistence

that enabled him to continue to compose in postwar Vietnam.

Peace is the root of music.1

-Nguy?n Tr?i, fifteenth century

Those who write the songs

are more

important than

those who write the laws.

-Attributedtoboth Pascal and Napoleon

first went to Vietnam in the summer of 1968 as a volunteer with Inter

I national Voluntary Services. Assigned to teach at Phan Chu Trinh Sec

English

School in D? I the task of a new

ondary N?ng, began learning language and

culture. Vietnamese, to put on

especially students, love cultural performances,

and I attended many. At these performances, in

girls who had dissolved

shyness when asked to repeat a simple English phrase in class sang boldly and

for large, appreciative audiences. In the late 1960s, one heard

professionally

music not at school functions but all around D? in other cities

just N?ng and

in South Vietnam. In coffee and restaurants, songs emanating from large

shops

JohnC. Schafer (jcsl@humboldt.edu) is professor emeritus in the Englsh Department at Hum

boldt State University inArcata, California.

xQuotedby Phong T. Nguyen inhis introductiontoNew Perspectiveson VietnameseMusic (1991,

vi). Nguy?n Tr?iwas a poet and a militaryadvisor toLe Loi, who defeated theChinese in 1427 and

proclaimed himselfking in 1428.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

598 JohnC. Schafer

roar of Honda

reel-to-reel tape recorders competed with the motorcycles and

on the streets outside.

military trucks passing by dusty

were a

Many of these songs composed by songwriter and singer named Trinh

Cong Son. If the event wasorganized by school officials, performers would

some of his love songs that didn't mention the war, but at unofficial

usually sing

a as "Love

gatherings, they would sing different kind of love song?a song such

a Person," which

Song of Mad begins,

I love someone killed in the Battle of Pleime,

I love someone killed inBattlezone D,

Killed atDong xo?i, killed inHanoi,

Killed suddenly in theDMZ.

It continues in this way,

I want to love you, to love Vietnam?

In the storm I your name,

whispered

A Vietnamese name,

Bound to you our

by golden-skin tongue.

In this song, we see some of the themes that Trinh Cong Son returned to again

and again: the sadness of war, the importance of love?love between

people

and

love for Vietnam, the native land?and a concern for the fate of people?for the

Vietnam and, by extension,

people of for all humankind.

Trinh Cong Som died six years ago, finally succumbing at the age of sixty

two to diabetes and other ailments that clearly had been too

aggravated by

much drink and too many cigarettes. Throughout Vietnam and in the cities

of the Vietnamese Melbourne to Toronto, from Paris to Los

diaspora?from

was an

Angeles

and San Jose?there outpouring of grief at his passing and

an for the approximately 600 songs he had left behind. In Ho

appreciation

Chi Minh City, thousands joined his funeral procession, and everywhere

there were cultural performances, some of them and shown on television,

taped

to say to someone who had

featuring young singers singing his songs good-bye

touched the hearts of millions. After a sold-out "An

attending performance,

of Music to RememberTrinh Cong Son," at the old French opera

Evening

house in Hanoi, the splendidly refurbished "Great Theater," on

April 29,

2001, I decided to seek reasons for what Vietnamese commentators call "The

Trinh Cong Som phenomenon"?that is, the extraordinary of Trinh

popularity

music.

Cong Son and his

is not to in

To call this singer's impact

phenomenal indulge hyperbole. Nh?t

Tien, a writer who now lives inCalifornia, calls Trinh Cong Sans music "the artis

tic work that had the clearest influence" because "it life directly"

penetrated

(1989, 55). Son was most influentialduring the the 1960s and 1970s, and his

most fervent admirers were Vietnamese from the region controlled by the

former Republic of Vietnam. During the war, Northerners were forbidden to

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh Cong San Phenomenon 599

listen to music the country was

from the South.2 After reunified in 1975,

however, Trinh Cong Son developed a national following, and at the time of

his death he was one of the best-known songwriters inVietnam. Though he com

in would be called "popular music"3?songs for people from

posed what English

all walks of life, not just the scholarly elite?well-known writers and critics have

called him a poet and written learned articles about him. The distinguished lit

critic Hi?n considers Trinh Son's song "At I

erary Ho?ng Ngoc Cong Night

Feel Like a Waterfall" one of the best love poems of the twentieth century

(NguyenTrong Tao 2002, 13).

For all these reasons, the Trinh Cong Son merits investigation.

phenomenon

based mostly on

What follows ismy explanationofTrinhCong Son's popularity,

what I have learned from conversations with Vietnamese friends and relatives

over the years and from accounts

published by Vietnamese that have appeared

since his death.4 I conclude that there are at least seven reasons for the Trinh

Cong Scm phenomenon: the freshness of his early love songs, the evocation of Bud

dhist themes, the rhetorical context of South Vietnam during the American war, the

ethos or persona that Trinh Cong Son projected, Son's discovery of the talented

cassette tape recorder, and Trinh Cong

singer Kh?nh Ly, the emergence of the

Son's ability to adapt after the war to a new climate. After providing a

political

briefbiographicalsketchofhisyoungeryears,Iwill develop thesepointsmore fully.

Early Years

Sans home was Minh

Huong, located on the outskirts of Hue in

village

central Vietnam.5'6 This village's name, "village of the Ming," suggests something

about his distant ancestry: Son was descended on his father's side from Chinese

associatedwith theMing dynastythatsettled inVietnam during the seventeenth

can be when the regions of Vietnam. The line of

2Terminology confusing discussing temporary

demarcation at the 17th parallel that separated theDemocratic Republic of Vietnam from the

or theRepublic

Republic ofVietnam from 1954 to 1975 splitthe central region. "SouthVietnam,"

of Vietnam, therefore included Vietnamese from central and south Vietnam (as well as northern

Vietnamese refer to the area south of the 17th as Mien Nam, the

refugees). usually parallel

"southern I will refer to this area as South Vietnam, or the South, and to the southern

region."

of South Vietnam (Nam B?) as south Vietnam. "Southerners" refers to

part Similarly, people

to inNam Bo.

livingsouthof the 17th parallel, "southerners" people living

3See my section on "The Cassette Recorder" for a discussion of how the English term

"popular

singer"applies toTrinh Cong Son.

4Most books about Trinh Cong Son published afterhis death include both newlywritten articles

and of articles. For the latter, in my author-date

reprints previously published parenthetical

citationswithin the body ofmy article, I listfirstthe date of the collection inwhich the article is

reprinted,then the date of originalpublication.

For thisaccount of Son's early life,I have drawn on Dang Tien (2001a), Ho?ng Ph? Ngoc Tu?mg

(2001/1995),Nguyen Dae Xuan (2001), Nguyen Thanh Ty (2001, 2004), Nh?t L? (2001/1999),

Trinh Cung (2001), and Sam Thuong (2004).

6I will sometimes refer to Trinh C?ng Son as Som, his given name, in order to avoid repeating

his full

name. It is not customary to refer to Vietnamese the name.

using only family

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

600 JohnC. Schafer

century when the Manchus defeated the Ming and established the Ch'ing dynasty.

Son was born in 1939, not, as it turned out, inMinh Huong but inDae Lac Province

in the central a to

highlands, where his father, businessman, had moved the family

toHue in 1943 economic

explore business opportunities. The family returned when

pressuresbroughton byWorldWar II forced his fatherto leave thehighlands.

Son attendedlocal elementary schools and was studying at a French lyc?e in

Hue when tragedy befell the Son's father,who ran a

family. bicycle parts business

and worked secretly for the revolutionary movement, was killed when he crashed

his Vespa returning from Qu?ng Tri. This was 1955, and San, sixteen at the time,

was the oldest of seven children?and his mother was expecting an

eighth.

the death of his father was an emotional and economic blow to Son

Though

and his family, he was able to continue his studies. During the academic year

1956-57, he studied at the Providence School (TrucmgThi?n hiru) runby the

Catholic diocese After passing his exams and receiving his first-level bac

inHue.

calaureate degree, he moved to Saigon, where he studied philosophy at the Lyc?e

So that he could avoid the draft, some friends helped him

Chasseloup-Laubat.

get into the Qui Nhon School of Education. After graduating in 1964, he

in a remote school for ethnic minorities in the

taught for three years primarily

near D? Lat, where he some of his most famous songs.

highlands composed

Son loved music from an He the mandolin and the bamboo

early age. played

flute before getting his firstguitar when he was twelve. "I turned tomusic probably

because I loved life," Son wrote, "but a twist of fate also played a part" (2001/1997a,

202).While studyinginSaigon,Son returnedtoHue on holidayand practiced judo

with his younger brother. He was hurt in the chest, and his recovery took three years.

The accident prevented him from getting his second-level baccalaureate, but itpro

vided time for him to It is clear that he never tomake

practice composing. planned

music his career. He described this time in his life, after his father died, when,

he didn't know it,he was poised on the threshold of fame:

though

I didn't take up music with the idea of making itmy career. I remember I

wrote my first songs to express some inner .... That was in the

feelings

years 56-57, a time of disordered dreams, of frivolous youthful thoughts.

In the greenness of this youthful time, like a fruit at the start of the

season, I loved music but had absolutely no ambition to be a musician.

Early Love Songs

Though theTrinhCong Son phenomenon did not reallybegin until themid

1960s, when Son's antiwar songs became popular, itwas his that

early love songs

first sparked interest in the young composer?songs such as "Wet Eye Lashes,"

7Quoted byDang Tien (2001a, 10). The original source isTrinhC?ng Son: Nhac va d?i (TrinhC?ng

Son: His Music and Life) (H?u Giang: Tong hop).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Son Phenomenon 601

Figure 1. Trinh C?ng Son on the balcony of his home on Nguyen Tnrcmg To Street in

Hue, circa 1969.

"The Sea Remembers," "Di?m

of the Past,"8 and "Sad Love."9 Mystery has

always surrounded

many of Som's songs, prompted by unanswered questions

their and this is true of his love songs.

regarding inspiration, especially People

wanted to know the identity of the girl who inspired the song. Stories circulated,

interest in the

gradually assuming the quality of myth, and they helped generate

singer. In recent years, Son and his close friends have cleared up some of the

a few songs. San, for

mysteries for example, explained that "Wet Eye Lashes"

was written as a for a named Thanh Th?y, whom San had heard

gift singer

as she sang because her mother was at

sing "Autumn Rain Drops,"10 crying

home dying of tuberculosis (2001/1990, 275). And "Di?m of the Past," perhaps

the most famous of all San s love songs and one of the best-known of all

modern Vietnamese love songs, was inspired, San explained, by

a

girl named

Di?m, whom San watched from the balcony of his house in Hue (shown

in as she walked Street to her classes at the

figure 1) along Nguyen Trucrng To

university(2001/1997b,178-80).

What was it about

these early love songs, besides the mysteries surrounding

their inspiration, thatmade them so appealing? San s contemporaries explain that

were his listeners, young people in the Southern

they appealing because they struck

cities

increasingly exposed

to

European and American songs, as newer than (m?i

hon) songs by other Vietnamese composers. Most of these older-sounding songs

8See II for a translation of "Diem of the Past," "A of Cannons for the Night," and

appendix Lullaby

"A Place for and Returning." For translations of fourteen of Son's antiwar songs, see

Leaving Joseph

Do Vinh Tai and Eric Scigliano (1997).

9In appendix I, I give the Vietnamese titles for all the songs I mention.

mira thu) is a "prewar" text.

"Autumn Rain

Drops" (Giot song. See explanation in

subsequent

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

602 JohnC. Schafer

were what Vietnamese refer to as "prewar" (tien chien) songs, a term that ismislead

reasons. It is it refers not to songs written

ing for several misleading firstbecause only

before the war to songs written soon after the

against the French but also during and

war. It is also because it is

to refer to sentimental love

misleading generally used only

songs composed during this period, not to patriotic songs, for example.

The term "prewar" probably became popular because many songs

composed

in theme and sentiment what were

during this period resembled called

"prewarpoems" (tha tienchien) composed in the 1930s and 1940s (Gibbs 1998a)

a were

by group of poets who heavily influenced by nineteenth-century French

romantic de Larmartine, Alfred Vigny, and Alfred de Musset,

writers?Alphonse

for example. Many prewar songs were prewar poems set to music. Important for

our purposes is the fact that prewar songs were still in the 1950s when

popular

Trinh C?ng San to compose. In fact, "Autumn Rain Drops," the song that

began

Thanh Th?y was singingin 1958 when she inspiredSan to compose his first

famous love song, "Wet Eyelashes," was a prewar song composed The

by Dang

Phong in 1939.11

Trinh C?ng San was certainly not the first composer of what Vietnamese

refer to as "modern music" (t?n nhac) or "renovated" or "reformed music"

(nhac cat each), terms used interchangeably to describe a new

Western-style

music composed by Vietnamese that firstemerged in the late 1930s (Gibbs

1998b). Prewar songs are considered modern or renovated songs; they form a

romantic

subcategory, their quality distinguishing them from other modern

songs, for Vietnamese contrast modern songs with

music?patriotic example.

folk songs, called d?n ca, a category that includes lullabies (ru con), rice-planting

and boat-rowing songs (ho), operatic songs (hat ch?o), and songstress songs (hat

ca triior hat ? d?o) (PhamDuy 1990; Nguyen 1991).

When the French introduced Western

music, Vietnamese composers first

wrote Vietnamese words for French tunes, but in the late 1930s, to

they began

compose modern Vietnamese songs, and that is when the terms t?n nhac

(modern music) and nhac c?i each

(renovated music) to be used.

began

However, because these first composers of modern Vietnamese music wanted

to compose Vietnamese songs, not French songs with Vietnamese

simply

words, worked to make their compositions echo the tunes and

they purposely

rhythms

of traditional folk songs. For this reason, Pham Duy calls these first

modern songsd?n ca m?i (new folk songs) (1990, 1). Both folk songs and reno

vated songs were based on poems. Folk songs were based on folk poems of anon

ymous authorship called ca dao-, some renovated songs were also based on ca dao,

but many were based on poems by known poets, including some who were still

living.

Because of their origin in poems, many renovated or prewar songs contain

nFor a descriptionof thissongand the influenceof itscomposer, see Pham Duy (1994, 80-87); for

an English translation,see Gibbs (1998a).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Scm Phenomenon 603

traces of traditional Vietnamese

poetic forms ?the form lue bat, for example

lines of six and eight words), or the famous seven-word (that

(alternating ng?n)

verse form that was inVietnam, as well as China.

T'ang popular

were not were in the

Though they officially banned, prewar songs rarely heard

North. Engaged inmobilizing themasses firstto defeat theFrench and then the

Americans and their allies, leaders of the Democratic of Vietnam did not

Republic

want to listen to sentimental and romantic songs. Prewar songs were,

people

however,heard often in theSouth:Theywere the songsthatformed thebackdrop

against which Sons innovations stood out. "Entering modern music [tan nhac] with

a new a new

spirit," says Dang Tien, "Trinh Cong Son gradually constructed

musical language that broke the old model of

renovation music [nhac cm each]

that had emerged only twenty years earlier" (2001a, 12-13).

What did Son do tomake his songsappear freshand new?Van Ngoc stresses

Son's new approach to were not restricted to the function of

lyrics,which, he says,

tellinga story

with a beginningand an end. "Theyhad a lifecompletelyindepen

dent, free. They could evoke beautiful images, impressions, and brief thoughts

that sometimes reached the level of surrealism; and between them sometimes

therewas no logical relationshipat all" (2001, 27). Son designed his songs to

make an end run around the conscious intellect in order to reach the heart

To

achieve this effect, he used the same

directly. techniques employed by

is is so a a mere

many modern poets, which why he

frequently called poet, not

songwriter.13

These techniques include purposeful incoherence (at least at the

level of logic); unusual grammar that pushes at the limits of what is

acceptable;

fresh diction, and metaphors;

images, startling word collocations; and rhyme,

both true rhyme and off rhyme.All of these techniques are evident in

"Di?m of thePast" (see appendix II). Though thebasic situationof the song is

in the rain for a visit from someone he loves?the

clear?the singer iswaiting

song is not a coherent narrative. "What does Tlease let the rain pass over this

to do with 'Let the wanderer a wanderer'?"

region' have forget he's asks Le

H?u. "It sounds like The man

talks chickens, the woman talks ducks'; as

a line from another into this one" (2003, 227).

though song has been plugged

Son's use of unusual grammar is seen in line 2: "Dai tay em may thud mat

xanh xao" (Your long arms, your pale eyes). In translating this line, my wife

and I have left out the phrase "may thu?" (many times, many periods of time)

because Son's grammar does not enable one to know for certain how this

phrase relates to the rest of the line.

12The distinction between "renovated music" and music" is not a clear one. As Gibbs

"prewar

(1998a) "In more recent years these songs [renovated music] have come to be called

explains,

nhac tien chien As I suggest, however, most consider to

[prewar music]." people prewar songs

be a romantic of renovated music.

subcategory

Son s is "mere" about

impact proves that there

13Trinh C?ng but

nothing songwriters, traditionally

in Vietnam, have been more than musical

poets respected performers.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

604 JohnC. Schafer

Though

in "Diem" (as inmany prewar songs), it is raining, it is autumn, and

leaves are other words and images are not clich?s. References to old

falling,14

temples, gravestones,and stones needing each other were not conventional in

prewar songs. Probably the most famous line of this song, "In the future even

stones will need each other," became famous because it contained a new and

A fourth use of unusual word collocations, is

arresting image. technique, Son's

related to what some critics have identified as a distinguishing feature of Sans

songs, namely, his frequent use of "d?i nghich," or opposition of ideas (Cao

Huy Thu?n 2001b; Tr?n H?n Thuc 2001), a feature that I will saymore about

later. In "Di?m," there is an unusual collocation in the second Une of the

second stanza, translated as "In the afternoon rain I sit San uses

the

waiting."

rain mua to describe the rain, an unusual

phrase "trips of pass" (chuy?n qua)

use of a word that is in such as

chuy?n (trips, flights), usually used phrases

"car or "train not to describe rain (Le

"plane trips," trips," trips" but periods of

Hou 2003, 227). Some better examples occur in the second stanza of another

Sans "Sad Love":

early love song,

Love is like a burningwound on the flesh,

Love is far like the sky,

Love is near like the mist of clouds,

Love is like a tree's shadow,

deep

Love shouts with in the sun,

joy

Love's sadness intoxicates.

stanza love to a burning wound, proof

The begins with the striking comparison of

that the war is beginning to occupy the songwriter. Then come references tomist,

clouds, sky, and sun, which are conventional but are used by Son to counter

rather than to fulfill expectations, as Dang Tien explains: "'Love is far like the

sense, but why 'near like the mist of clouds'? ... 'Love shouts with

sky' makes

in the sun' is it should be to 'Love flies in the

joy right, but opposed sadly

rain.' we

Why do get 'intoxicates' here?" (2001a, 11).

Tien compares "Sad Love" to Do?n Chu?n and Tir Linh's "Send the

Dang

Wind toMake theClouds Fly," a prewar song composed in 1952 or 1953 but

stillpopular inVietnam during the 1960s and 1970s (I heard itmany times in

coffeehouses inHue and D? N?ng during thewar). It begins as follows:

Send thewind tomake the clouds fly,

Send the to the flower,

many-colored butterfly

Send also the blue of a love letter,

moonlight pale

Send them here with the autumn of the world.

14Vietnamese find it hard to resist leaves. to Tao,

songwriters falling According Nguyen Trong

fiftyof themodern songs ranked in the top hundred relyon the repeated phrase l? roi (leaves

fall) (2002, 13).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng So'n Phenomenon 605

to stanza from Son's song has fresh

According Dang Tien, although the opposi

tions, these lines consist of conventional images and juxtapositions: wind

cloud, butterfly-flower, moonlight-autumn.

A final poetic true

technique, rhyme?both rhyme and off rhyme?is used

to tie his

skillfully by Son compositions together. Other songwriters used

but itwas an device for San. Tr?n H?u Thuc says

rhyme, especially important

that in some famous Trinh C?ng San songs, one "sings rhyme," one doesn't

"sing meaning" (2003, 56). Iwould put "Di?m" in this category. Though the frag

mented meaning jars the listener, the repetition of similar-sounding words at the

ends of lines unifies the song and has a soothing effect. Because Vietnamese spel

is one can see how much is used in "Di?m"

ling quite phonetic, rhyme by noticing

the similarspellingsof the finalwords in the lines.

In Son to adopt a new to

explaining what motivated approach lyrics, Dang

Tien points to the vibrant and intellectual climate in southern Viet

cosmopolitan

namese cities between the two Indochina Wars (2001a, 13). "People read Fran

?oise in at the same time with Paris," Dang Tien says. "In the cities,

Sagan Saigon

in coffee houses, discussed Malraux, Camus, and also Faulkner,

especially people

Gorki,Husserl, Heidegger" (14). In Hue, Son hung outwith a highlyeducated

group of friendsthat included the artistsDinh Cucmg and B?u Chi, thephiloso

pher andwriterHo?ng Ph? Ngoc Tucmg, thepoet Ng? Kha (whoalso had a law

degree), and the French professor and translator B?u y, head of the French

Department at theFaculty of Pedagogy at Hue University (Dinh Cucmg 2001,

58). San was clearly exposed

to modernism

through

his own

study

of philosophy

and through discussions with his close friends, and sowhen, for

example, he used

words that frustrated expectations, when he disdained easy meanings, when he

an emotional not a he was no doubt moved

opted for logical coherence, by

some of the same forces that had affected Guillaume in France

Apollinaire

and T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Ezra Pound in England and

America.15

Another member of Son's circle of friends, Thai Kim Lan, who in the

early

1960s was at the

University of Hue, the

studying philosophy emphasizes

ofWestern on the youth of Hue

impact philosophy, particularly existentialism,

at this time. Concepts such as "existential angst," and "the

"being nothingness,"

of Ufe," and the myth of she says, hotly debated

meaningless Sisyphus were,

(2001, 84). Though San had studiedphilosophyat a French lyc?e,according to

Thai Kim Lan, he would usually sitback and listenduring these discussions,

but then later, to the surprise of his friends, he would compose a song and

were

"sing philosophy." His songs, Thai Kim Lan argues, simpler

versions of

the ideas theywere discussing,and theyhelped those inher circle cut through

15"When I was still in school," Son told Tu?n Huy, "I would take with me a book of poems

by Apol

linaire and murmur to each word of his poems and gaze out at the

myself outstanding dreamily

white clouds driftingby thewindow" (quoted inTu?n Huy 2001, 31).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

606 JohnC. Schafer

the intellectual knots they had tied for themselves. Thai Kim Lan suggests that

when, in a song called "The San sang that "there is no such

Unexpected,"

as the first death, there is no such as the last death," he was

thing thing

on the In

working philosophical problem of defining "beginning" and "end."

"The Words of the River's Current," he was on the problems of

working

to Thai Kim Lan, it is his

"being" and "nothingness." According incorporation

of these newer philosophical notions into his songs that

distinguished

his music

from previous composers and made it to young people (83).

appealing

Son's recently rediscovered "The Song of the Sand Crab" a

provides good

of how Son's in French influenced his composition.

example training philosophy

In this long song (trudngca), clearly inspiredby Albert Camus' "The Myth of

Son uses Vietnam's symbol of endless and futile labor, the sand crab,

Sisyphus,"

to present a view of life that is as bleak as Camus',

although the work does

suggest thepossibilityof salvationthroughlove. Performedchorallyin 1962 by

Son's fellow students at the Qui Nhon School of Education, itwas well received

at the timebutwas never published or recordeduntil theHue historianNguyen

Dae Xu?n interviewed students who remembered it Dae Xu?n 2003,

(Nguy?n

32-33, 39-51; see also Nguyen Thanh Ty 2004, 15-18). Son's philosophical

in

lyrics "Song of the Sand Crab" and other works helped make his songs new,

but he was careful to make sure the ideas they conveyed were not too strange

or "I have Son wrote, "and so I have wanted

foreign. always liked philosophy,"

to put into my But then he was

philosophy songs." specifies that what he aiming

for was "a soft kind of philosophy that everyone can understand, like in a

folkpoem or in a lullabythata mother singsfor her child" (2001/1997a,202).16

But itwas

not only the words of Son's songs that made them appear fresh

and appealing: His songs were more modern sounding than the songs composed

such as Do?n Chu?n and the early works of Van Cao and

by prewar composers

Pham Duy, all contemporaries of San but older. What made Son's songs sound

modern? Son achieved a more modern effect by not echoing?or by echoing

much more faintly?the prosody of declaimed poetry. Avoiding these echoes

was not easy because many prewar songs carry, as I pointed out earlier, the

traces of familiar poetic meters. Dang Tien, for example, argues that

these lines from Do?n Chu?n and T? Linh's's "Send the Clouds" echo the

famous T'ang seven-word (that ng?n) verse form that was in Vietnam

popular

and China:

L? v?ng t?rngc?nh roi t?ng c?nh (sevenwords)

One by one each golden leaf

Roi xu?ng ?m th?m tr?nd?t xua (sevenwords)

Falls silentlyon old ground;

For more informationon Trinh C?ng Son's "soft philosophy," including the influence of

Buddhism and existentialism,see JohnC. Sch?fer (2007).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Sen Phenomenon 607

In San s songs differed from his Van

explaining how predecessors, Ngoc argues

that"whenone sings songs likeThe Sadness ofAutumn Passing' (1940) byVan

Cao or a (1945) by Pham Duy,17 one can't refrain from

'Song of Warrior's Wife'

each line, each word, as if one were a

declaiming singing songstress song (ca

As in the ears, it's as if one can hear the moon

tr?)}8 they sound lute and the

singer's lute, or the drum

and bamboo castanets!"19 (2001, 27). In contrast,

Son's songs verse forms. One reason may be

rarely evoke these well-known

Son's education in a French Viet

lyc?e, where, unlike his friends who attended

namese schools, he was not made to and memorize written in

study poems

traditional Vietnamese and classical Sino-Vietnamese verse forms Tien

(Dang

2001a, 11; Nguyen Thanh Ty 2004, 101).

Buddhist Themes

In comparison toworks were fresh and

by these older composers, Son's songs

new, but theywere not so unusual that they sounded foreign. The mood of Son's

music remained traditional?sad, dreamy, and romantic?and thus his songs

were toVietnamese simi

nicely attuned expectations, which had been shaped by

larlysad lullabiesand prewar songs (VanNgoc 2001, 27). This sadmood and the

messages of many of Son's songs probably reflect the influence of his Buddhist

background. San admitted to the influenceof his faithand of his hometown of

a very Buddhist "Hue

Hue, city ringed by dozens of

pagodas: and Buddhism,"

he wrote, "deeply influencedmy youthfulemotions."20Though his friendThai

Kim Lan says that San was dealing with Western metaphysical problems

in his

songs, his as she herself ends up admitting, could be con

philosophy, probably

sidered Buddhist as well. "Now as I reflect I realize that ... those new ideas

were not new but were found in Buddhism"

(2001, 84).21 When an interviewer

was a

suggested there "strong current of existentialism" in his songs, Son replied,

"The supreme master of existentialism was the Buddha because he us that

taught

we must be mindful of each moment of our lives" (2001/1998,211). San

clearly

drew on bothWestern philosophyand Buddhist thinking. As he said,he aimed

for a simple philosophy, not a one (200171997a, 202).

"systematized"

1

Pham himself finds echoes of inVan Caos and in his own com

Duy T'ang poems early songs early

positions (1993, 13).

8Ca tr?, also called hat a d?o, translated as "chamber music" or was a

usually "songstress songs,"

diversion for learned men who went to houses to hear them sing ancient poems or

songstresses'

poems of their own (the men's) composition.

9These are traditional instruments used to accompany a ca tr?.

songstress singing

20From"Chu t?ichum?nh c?ng l?b? d?u" (TheWords Talent and Fate Both Lead toTurmoil), an

with Son reprinted inNguy?n Trong Tao et al. (2001, 221).

undated interview

21Tr?n H?u new and non

suggests that Son's

Thuc to word collocations

approach lyrics (unusual

canonical for made some familiar Buddhist and Taoist notions fresh

grammar, example) appear

and new (2001, 77). This new "packaging" of traditionalideas may be why Thai Kim Lan and

her circle did not immediatelydetect Buddhist themes in Son's songs.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

608 JohnC. Schafer

are not are in

Though they

certainly systematized, Buddhist ideas expressed

many songs, particularly the notion of v? thu?ng, or impermanence, including

the idea that death is an event in a chain of cause and effect that leads to

rebirth, and recognition that, as the Buddha said, "Life is suffering." Imperma

nence is a theme of many songs: In the world of Trinh is

C?ng San, nothing

forever?not not a love not life. We see this theme in

youth, relationship,

"Flowers of Impermanence," an in which San

uncharacteristically long song

sketches the phases of a love relationship: the search for someone, the discovery

of love, and then the inevitable ending. It appears also in the song "To Board," in

which all living things, including the songwriter, are depicted as residing only

in this world, like a boarder in a rooming house:

temporarily

The bird boards on the bamboo branch,

The fish boards in a crevice of water.

spring

I myself am a boarder in thisworld,

In one hundred years I'll return to the edge of the sky.

There is sadness in

impermanence, of course, but also peace of mind if one rea

lizes that the end of a lovingrelationshipand of life itselfis also a beginning; a

is also an arrival. In Son's songs, to

departure always going leads coming?and

vice versa?and of a circle often. "The Sea Remembers," for

images appear

"Tomorrow you leave / The sea remembers your name and

example, begins,

calls you back." A later song, "A Place for Leaving and Returning," is, as the

title suggests, permeated by this idea of the inseparability of arriving and depart

a song about death?it was sung at all Son's

ing. Though commonly considered

memorial concerts and a as his coffin was carried to his

played by saxophonist

grave?in this famous song, the sadness of leaving and death is mitigated by

the linkto returningand to rebirth(Cao Huy Thu?n 2001a).

Some Vietnamese, and some Westerners

listen to his songs and read

who

translations of his lyrics, find Son's songs "weepy," even morbid. It is an under

standable reaction: Most of his songs are sad; many contain references to

death. San admitted to being obsessed with death since an early age, perhaps

because of the earlydeath of his father (2001/1998,207).23 Certainly, too, the

war

heightened every Vietnamese's consciousness of death. "I love someone

just killed last night," San sings

in "Love Song of a Mad Person," "Killed by

chance, killed with no / killed without hate, dead as a dream."

appointment

San is not concerned only with the death of others: His own death is never far

from his mind. He refers to it directly in some songs, for example, in "Next to

a Desolate Life": "Once I dreamed I saw it's true tears

myself die, / Though

so I and the sun was in the

fell I wasn't sad, / Suddenly awakened rising"; and

22See II for a translation.

appendix

23"Inmy childhood Iwas frequentlyobsessed with death. In dreams I often saw the death ofmy

father" (TrinhC?ng Son 200371987b, 182-83).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Scm Phenomenon 609

I In other songs, he

"Unexpected": "Very tired lay down with the eternal earth."

refers somewhat more obliquely to his own from this world?for

departure

in "Sand and Dust," "There'll Be a

example, Day Like This," and "Like Words

of Goodby." In Son's songs, death and life interpenetrate each other, each

to the other. The to many of his songs that he

giving meaning lyrics suggest

livedhis lifewith death inmind.

In as "an

death that affects one's

experiencing anticipatory conception"

earthly

existence

(Kierkegaard 1846, 150), Son was following the recommen

dations of the existentialists. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, young intellectuals

in Southern cities were fascinated existentialism, and Son's close

by European

friends emphasize his intense interest in it.24 It is therefore probably not a coinci

dence that death appears to have been for San what itwas forMartin Heidegger

and Karl Jaspers: a "boundary situation" that gives meaning to life. "I love life

with the heart of someone who despairs," San wrote in the introduction to a

song collection (1972, 6). This despair or sense of desolation (tuyetvong) that

many of Son's songs should be seen, I believe, as similar to

permeates

existential "dread"?an in the face of or

anxiety nonbeing nothingness. Paradoxi

to what called "authentic" existing, as Ren? Muller

cally dread leads Heidegger

explains,

In (das Nichts), the intuition of what

Heidegger's ontology, nothingness

itmeans not to exist, is the basis for authentic

existing. To Heidegger,

onlywhen I recognize and accept that I will lose all I know of my

more to the am it at this very

earthly being?even point, that I losing

moment?can I come to terms with what my life is. I

Only then, when

am free to facemy dying,am I free to livemy fullestlife.

When I can

let go of theworld, I will receive theworld.When Ifeel theVoid ...,

the ground of being appears under my feet. (1998, 32-33)

was not a Buddhist, this is, as M?ller

Though Heidegger points out, "a paradox

worthy of Zen. Tathata (suchness), the true meaning of the world, or more

we concounter, comes

simply, the truth about all only after achieving sunyata

(emptiness)" (33). An appreciation for the transitoriness of life that dread awa

kened in the existentialists resembles the Buddhist idea of vo thucmg, or imper

manance. Thereare many similarities between Buddhism and existentialism, as

scholars have pointed out.2 In his songs, Son blended Buddhist and existentialist

ideas to produce an artistic whole that his listeners found new and a little

24See B?u Y (2003, 18-19, 89-91), Ho?ng Ph? Ngoc Tuong (2004, 23-25, 120), Thai Kim Lan

(2001, 82-86), and Sam Thuong (2005).

25Zen is only one of school of Buddhism, and there are, of course, differences between Zen and

existentialism. For a discussion of the similarities and differences, see (1979) and

George Rupp

Ren? Muller (1998). In "Death, Buddhism, and Existentialism in the Songs of Trinh C?ng Som,"

I argue that Son's "softphilosophy" isprimarilyBuddhist (Sch?fer2007).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

610 JohnC. Schafer

not too strange.

strange?but By incorporating Buddhist themes into his songs,

San his listeners, most of whom were Buddhists, accept death and suffer

helped

ing. They found?and still find?his songs not morbid but consoling.

Trjnh C?ng Sew and the War

The songs in Son's firstpublished collection, Songs of Trinh C?ng Son,

released in 1965, were love songs, but we can see the war intruding in some of

them. "Sad Love," the last song in this collection, opens with the line, "Love is

like a [military]shell, a heart that is blind." In his next collection, Songs of

Golden Skin war becomes

(1966-67), not a source of to talk

just metaphors

about love but

the major It is these songs more than any others that

topic.

created the Trinh C?ng San phenomenon, songs such as "Lullaby of Cannons

for the "Vietnamese Girl with Golden Skin," "AWinter's Fable," and

Night,"26

"A Mother's These songs are antiwar in the sense that

Legacy." they express

sadness at the death and destruction the war is causing, but are also love

they

songs that ask listeners to cherish love between lovers, between mothers and chil

dren, and between all people of golden skin. In these songs, to use a phrase that

became a clich? in America, San urges people to "make love, not war."27

But itwas not just the songs, itwas also the public performance of the songs

that sparked the Trinh C?ng San phenomenon. A watershed event was a per

formance at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Saigon in 1965. Organized

by some of Son's friendsand attendedby artists,intellectuals,and high school and

it took in an open space behind the university. This was

college students, place

Son's first performance before a large audience, and he said that he looked on

it as an "experiment to see if he could exist in the hearts of the (2001/

people"

278). He answer in the form of an enthusiastic

1997c, got his response, which

he later described in this way:

with me a of twenty songs about the native land, the

Carrying light load

dream for peace, and songs that now are called "antiwar," I tried my best

to someone who wished to convey his inner to his

play the role of feelings

26See II for a translation.

appendix

27It isdifficulttodistinguishSon's antiwarsongsfromhis songs about love and his native land.Love

such as "Di?m of the Past" and songs about the human condition assumed an antiwar

songs quality

when were the for peace. Michiko Yoshi, a researcher associated with the

they sung during struggle

University

of Paris, finds sixty-nine antiwar songs in the 136 songs that Son composed between

1959 and 1972 (see Dang Tien 2001b, 130). For my purposes, I consider Son's antiwar songs to

be those expressing a desire forpeace that are found in these collections: Ca Kh?c Trinh C?ng

San (Songs of Trinh C?ng Son, 1966), Ca Kh?c Da V?ng (Songs of Golden Skin, 1966-67), Ca

Kh?c Da V?ng 11 (Songs of Golden Skin II, 1968), Kinh Viet Nam (PrayerforVietnam, 1968),

Ta Ph?i Th?y Mat Tren (WeMust See the Sun, 1969), and Phu Kh?c Da V?ng (More Songs of

Golden Skin, 1972).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Sem Phenomenon 611

audience. That concert had a beautiful

effect on both the presenter and

the audience. One was in the end the

song requested eight times, and

to

audience

spontaneously began sing along with the singer. After the

concert I was an

"compensated" by having the privilege of sitting for

hour to sign the dittoed song sheets that were distributed for listeners.

(278)

San took shortunauthorized leaves fromhis teachingjob inBao Loe toperform

at this and other concerts in an to cover his classes

Saigon, forcing aging teacher

and stretchingthe toleranceof his schoolprincipal (NguyenThanh Ty 2004, 41,

96). In the summer of 1967, Sans career ended when he and some of

teaching

his friends, also teachers in Bao Loe, received draft notices. San, however, never

for duty and never served in the army. He moved to Saigon and

reported began

a rather Bohemian life. For two years after receiving his induction notice,

living

San was able to live a life. He avoided army service by a

fairly normal fasting for

month each year and drinking a

powerful purgative called diamox that lowered

his weight enough to make him fail his medical exam. But when the third year

rolled around, he feared his health was not strong enough to fast and purge

himself again, and so he became a draft For several years, he lived like

dodger.

a homeless person in abandoned and dilapidated prefabricated

housing behind

the Faculty of Letters. in amenities, this site had the

Though lacking advantage

ofnotbeing checkedby thepolice.He would sleep on a cot in theprefabhousing

or on the cement floor of a artists that had

meeting place for young sprung up

nearby.As forpersonal hygiene,he washed his face and brushed his teeth in

one of the

nearby coffeehouses.28

When his songs became 1968 Tet Offen

increasingly popular and, after the

sive, increasingly antiwar, the government of Nguyen Van Thieu issued a decree

banning their circulation.29 This brought Son increased attention from Vietna

mese and foreign journalists who pursued him for interviews. una

"Suddenly,

Son wrote, "I became famous... . I'd escape from Saigon to Hue

voidably,"

and a few days later I'd see of different skin colors, from different

people

countries, appear at my door.... I had to live frivolous moments in newspapers

and magazines and before camera lenses until ten

days before the city [Saigon]

was liberated" If

completely (2003/1987a, 181-82). foreign journalists could

a

find San, why couldn't the police? This remains murky and controversial ques

tion. Some say he was an air force officer named Liru Kim a

protected by Cuang,

close friend of Sans who may have been able to issue him some false enlistment

papers (Nguyen Thanh Ty 2004,115). Others say that Liru Kim Cuong was not a

powerfulenough figureto help Son and thathis keyprotectorwas Nguyen Cao

28NhatLe (2001/1999,134-53), Ho?ng Ph? Ngoc Tucmg (2001/1995,23-27), and Nguyen Thanh

Ty (2001, 2004) describe thisperiod of the singer'slife.See also TrinhC?ng Son's interview

with

Ho?i Anh (2001/2000, 119-120) and his "MyDraft Dodging Period" (2003/1987a, 179-82).

to Dae Xuan (2003,100), this was Decree No. 33, issued on 8,1969.

29According Nguyen February

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

612 JohnC. Schafer

Ky, prime minister from 1965 to 1967 and vice president until 1971. Dang Tien,

citing several sources, says thatNguyen Cao Ky befriendedTrinh C?ng San

because he liked the artist and was eager to garner the support of progressive

intellectuals and to repair relations with the Buddhist movement in Hue,

which he had helped crush in 1966 (2001b, 187).

One cannot understand the Trinh C?ng San phenomenon without under

context in it cities

standing the social which occurred?the of the South. When

Son took the stage at the University of Saigon in 1965, he was operating in a par

ticular rhetorical situation. Young men were being drafted and killed, artillery

batteries boomed in the

night, Russian-made rockets were in

city

landing

streets, and American were These events set the rhetorical

troops everywhere.

tinder, and San the spark. Van Ngoc emphasizes this connection

provided

between Son's and the created the war: "The

songs exigency by phenomenon

of Trinh C?ng San, or more accurately the songs of Trinh C?ng San, can only

be explained in terms of historical and social causes: without the

reality of the

war and the resentment it fostered, without the of confusion that

atmosphere

enveloped the youth of the cities, without the sharing of and emotions

feelings

between and audience, there would never be these

singer songs" (2001, 26).

Of course, one has to know how to seize the rhetorical moment, and San,

in his love songs away from the clich?s of romantic prewar

already moving

songs, was sensitive and talented to know what this new situation

enough

a new kind of love song, a song for the

demanded: suffering land and the

of Vietnam, a such as "A of Cannons for the

people song Lullaby Night,"30

which contains this refrain:

Thousands of bombs rain down on the

village,

Thousands of bombs rain down on the field,

And Vietnamese homes burn bright in the hamlet;

Thousands of trucks with and

Claymores grenades,

Thousands of trucks enter the cities,

Carrying the remains of mothers, sisters, brothers.

As these lines reveal, Son's antiwar songs differed from his earlier songs, not just

in matter but also in attention

subject technique. Whereas he caught people's

sometimes even surreal love songs, the

with illogical, metaphysical, lyrics of

Son's antiwar songs are logical and very realistic. He mentions actual battles

(Battle of Pleime, Dong Xo?i) and weapons (Claymores, grenades). Compared

to his love songs, which do not tell a coherent story, Son's antiwar songs are

much more story-like and

some?"Vietnamese Girl with Golden Skin," for

a story with a clear Htru Thuc suggests

example?tell beginning and end. Tr?n

thatwhen one looks at Son's total oeuvre, his antiwar songs stand out as atypical,

their realism and clear logic distinguishing them from his love songs and songs

30See II for a translation of this song.

appendix complete

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng ScvnPhenomenon 613

about the human condition. They sound, he says, like "reports on the war" (2003,

63).Why did San changehis approach towriting lyrics?

TranH?u Thuc says it is

because Son wanted to send a "clear about the war and the necessity of

message"

peace (58).

If his message was communicated successfully?and the almost immediate

of his antiwar songs suggests that itwas?it is no doubt because, in

popularity

these songs, Son gave voice to the private in the

thoughts of many, becoming,

process, the for an entire In the tributes to

spokesperson generation. many

San written since his death, the authors thank him for saying what

they could

not themselves express. "He's B?i Bao Truc, in a

gone," says typical tribute,

"but we'll always remember him, always be in his debt, to him for

grateful

us those are hardest to

saying for things that say" (2001, 62). "His voice," says

Biru Chi, "was like an invisible thread that quickly unified the private moods

and destinies of individualslivingin Southern cities" (2001, 30).

In the Son was a talented

public presentation of his songs, greatly aided by

someone so to Sans success that she will

singer named Kh?nh Ly, important

be described in a separate section. San met Kh?nh in 1964 when he visited

Ly

the central

highland city of D? Lat. Nineteen years old at the time, she was

singingat "NightClub D? Lat." Though Kh?nh Ly was not yetwell known,

Son sensed immediatelythat "her singingvoice was right for the songs [he]

was writing" (2001/1998,207). They struckup a partnership,and soonKh?nh

was

Ly singing only his songs and Son began writing songs with her voice and

talents inmind. In 1967, Kh?nh Ly and San at univer

began appearing together

sities in cities and at a or the

Saigon and Hue and other place called "Qu?n Van,"

"Literature Club" in to their fame," Kh?nh Ly

Saigon. Referring "phenomenal

says that "it all at the Literature Club," a venue that she describes in

began

this way:

The Literature Club, with a name easy to remember and so nice, sprang

an .... The roof was made

up in

unprotected spot in the heart of Saigon31

of leaves and old pieces of plywood tied together; the kitchen was smaller

than the one here [an apartment in Montreal]32 and was used only to

make coffee. People had to find a place to sit on the cement floor

amidst pieces of broken bricks and weeds. But when I was young that

place forme was themost beautifulof gatheringplaces (2001, 57).

San was in Hue Tet Offensive and saw the corpses strewn in the

during the

streets and rivers, on the steps of empty homes, and in the famous

berry field

where so many bodies were found, many of them apparently killed by National

31Itwas built on the foundationof a well-known colonial prison called Kh?m Lern ("The Big Jail")

andwas within thegrounds of theFaculty of Letters,Universityof Saigon (PhamDuy 1991, 283).

32Kh?nh lives in Southern California, but she met Son inMontreal in 1992. Son was inMontreal

Ly

visiting some of his siblingswho had settled there.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

614 JohnC. Schafer

Front and North Vietnamese execution

Liberation squads. Two of his songs,

on the and "A for the written at this time,

"Singing Corpses" Song Corpses,"

are the most antiwar songs and the most A composer

haunting of all his graphic.

who had begun writing dreamy songs of wet eyelashes and fleeting romances,

San now was writing of corpses and driven mad by the war. In these

people

Nhat Le "It was as if he was

songs, says, toying with the devil and with death,

was he was stunnedby thepain of his country"(2001/1999, 146).

but the truth

The first song has a sprightly cheerful rhythm, but when one focuses on the

words, it becomes clear that it is about people driven mad by the war, like this

mother who claps over the corpse of her child:

Afternoons on the hills, on the

singing corpses?

I have seen, I have seen the

by garden?

A mother clutchingher dead child.

A mother over her child's

claps corpse,

A mother cheers for peace?

Some for

people clap harmony,

Others cheer ...;

catastrophe

I came to Hue after the Tet Offensive and lived with a Vietnamese

family within

the Citadel area. Across a small store that sold music

the street was tapes, and

the owners would these sad songs over and over, to attract

play probably

As a result, they are seared on my memory, especially these lines from

buyers.

"A

Song for the Corpses":

Which corpse ismy love

Lying in that trench,

In the

burning fields,

those potato vines?

Among

The Ethos of Trinh C?ng So'n

Another important ingredient of the rhetorical situation is the ethos of the

or in this case, the a can seize

speaker, singer. In other words, whether singer

the rhetorical moment depends not only on s

the quality of the singer message

but also on the audience's perception of the character of the message deliverer.

In terms of ethos, San had two advantages. First, he was not associated with any

or In the environment of South

political religious faction. heavily politicized

Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, itwas difficultforVietnamese to finda voice

trust. were controlled

they could Newspapers by the government, officials?

both military and civilian?tailored their comments to fit the current propaganda

theme, and teachers were afraid to discuss political issues for fear of being

accused of being Communist Activists on the far left, many

sympathizers.

working underground for the Communist movement, were also suspect. Son,

however, kept his distance from the various political factions, and his name

was never linked to any of them. He had friends, such as the writer Ho?ng

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Sem Phenomenon 615

Ph? Ngoc Tir?ng, who joined the Communist movement in 1966 and other

friends,such as TrinhCung (no relation),who were in theArmyof theRepublic

of Vietnam. his friends were active in the Buddhist movement in

Though many of

Hue, San never let himself become a for the Buddhist cause. Son's

spokesperson

friend Biru Chi says Son "didn't act on behalf of any '-ism' unless itwas human

ism ... . In his antiwar music,

he had no political intention at all: was

everything

done on orders from his heart" (2001, 30). In Dang Tiens view, the people's per

no ulterior motives "was the reason for

ception that Son had political primary

Trinh C?ng Son's quick success, for his becoming a almost over

phenomenon

night" (2001b, 188).

Sans second advantage in terms of ethos relates to his

style and personality.

He was of average for a Vietnamese, had a frail build, and wore

height quite large

with horn rims. When he sang in front of audiences, he

glasses, usually large

would introducehimself and Kh?nh Ly verybrieflyand then theywould sing.

He in the soft tones of his native Hue accent, which his audience found

spoke

(Some Vietnamese believe the northernis accent the

appealing. domineering,

southern too free and unrefined.) He was

"the kind of person who

perhaps

not fear," says a voice that was

inspired love Dang Tien, with "friendly, creating

the illusion inmany that they were close to him, not real close but

people maybe

not distant" (2001b, 184). Imet Son several times inHue at his home on

certainly

To Street. I knew wanted to interview him, and so I

Nguyen Tru?ng Journalists

would ask students who knew him tomake the arrangements. At one meeting, his

friend Biru Chi was Son would answer if

present. questions politely and,

a song, on a scratched and battered old

requested, sing strumming guitar. He

struck me to be as his friends describe modest and unas

always just him?very

manner was success because

suming. Sans unaffected important to his in South

Vietnam the 1960s, the young students who first embraced

songs his

during

formed a relatively small community. Performances were small and personal,

and so the ethos of the singer was an important factor.

To appreciate Son's it is instructive to compare him to the compo

advantage,

ser Pham Son's closest rival in terms of fame and influence. There

Duy, perhaps

are several reasons Pham

Duy could not connect with urban youth in Southern

cities as as Son. He was

twenty years older, for

one

effectively thing. By the mid

1960s, he had studied music abroad in Paris and already had an established repu

tation as a In was less modest?that

leading composer. personality, he is, less shy

about And he was a northerner who the Viet Minh move

self-promotion. joined

ment in the 1940s but laterbecame disenchantedwith communismand fled to

the South, where he became a a series of anticommunist

supporter of regimes.

He was a friendof the legendaryCIA agent Edward Lansdale and used to

attend "hootenannies" at Lansdale's

private residence (Pham Duy 1991, 218).

He was also a member

of the Film Center, taught at the National School of

Music, worked weekly with the government radio station, and cooperated with

the U.S. Information Service on various projects. Because they recognized him

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

616 JohnC. Schafer

as an in Vietnam him to

important cultural figure, U.S. officials arranged for

make several trips to the United States. In short, he was not neutral, and so

some not be trusted.

people felt he could

When Pham Duy's collection Ten Songs of the Heart in the mid

appeared

1960s, it received a mixed reaction. Some young people loved his songs,

which, like Son's, talked of peace and reconciliation, but others reacted with sus

"In his

picion. Dang Tien reports, "Pham Duy sang with

Songs of the Heart,"

next to the old rice field,'33 but

great fervor T will sing louder than the guns

then he put on a black shirt and stood with groups involved in the Rural Recon

struction Program" (an unsuccessful attempt by the Saigon regime to win over

people in the countryside) (2001b, 186). By themid-1960s, Pham Duy had

lost his ability to appeal to

peace-loving students, especially those on the

political

left.Ho?ng Ph? Ngoc Tu?mg, a close friendof Son'swho leftHue before theTet

in 1968 to some students

Offensive join the Communist movement, writes that

loved Pham Duy's Songs of the Heart, but left-wing students considered the col

lection "a piece of warfare designed to soften the blow of American

psychological

troops" (1995, 55). Pham Duy himself appears to admit thathe had a political

in In his memoirs, he

objective writing Songs of the Heart. lumps this collection

in with other works "of a social service nature, songs for the

Ministry of Infor

mation, the Open Arms Program, the Army, and the Rural Reconstruction

Program" (1991, 218-19).

Not all Southerners, of course, Trinh C?ng San and his antiwar

appreciated

His as Biru Chi have real consequences:

songs. songs did, points out, "They got

not a few young to look at the and of the war, and

people inhumanity cruelty

them to hide from the draft or desert. In the eyes of those who

encouraged

held power in the old regime, San was someone who destroyed the will to

of the troops" (2001, 31). This was, of course, why the Saigon regime

fight

a futile conse

made attempt to ban his songs. That his songs had these real

quences endeared him to people like B?u Chi, who painted antiwar paintings

and spent time in prison for his antigovernment views, but the implication that

San was in some way responsible for the Communist victory troubles others

who do not share B?ru Chis radical politics but love his songs. These friends

and fans reveal their uneasiness to the term "antiwar" to

by refusing apply

Son's songs about the war.34 Pham Duy and Trinh Cung, both of whom now

live in California, object to the term. Trinh Cung, an old friend of Son's who

was in the of Vietnam, argues that "antiwar" is not the

Army of the Republic

proper term because "it suggests a the accepting of respon

judgement, suggests

we say that Sans wartime

sibility for the Souths defeat." Trinh Cung suggests

works are about "the fate of the Vietnamese (2001, 79).

people"

Tien the opening line from the second song in Pham collection h?t to"

33Dang quotes Duy's "Ti?ng

(ALoud SingingVoice).

34See, forexample, Trinh Cung (2001, 79).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Son Phenomenon 617

Tr?nh C?ng Sotm and Kh?nh Ly

After 1975, many young female singers sang Son s songs, including his sister,

Trinh V?nh Trinh. But for Vietnamese of Sons generation, Trinh C?ng Son will

to Kh?nh to

always be linked Ly, the singer who presented his songs admiring

fans at the Literature Club in Saigon, at performances at universities, and then on

cassette tapes. Trinh C?ng Son had a good voice, and at concerts, he would sing

half the songs by himself and several duets, and Kh?nh Ly would sing the rest.

But Son's voice was not as strong or as beautiful as Kh?nh Lys. Van Ngoc describes

Kh?nh Lys voice when shewas a young singer just beginning to perform Son s songs:

[It] could drop very low, very deep, but also could rise very high, a strong

voice, strong-winded, rich inmusical quality. Kh?nh Ly always sang with

the correct tone, rhythm, and modulation of the voice ... .It was a voice

that still had the freshness and spontaneity of a twenty-year old, but also

seemed to convey sadness as well. A voice that could be flirtatious in

a lovable way in romantic songs but also become angry and sad in the

antiwar songs. (2001, 26)

Like San, Kh?nh Ly lived an unorthodox life. Her father, like Sans, had been

involved in the resistance and died after a stint in prison when she

four-year

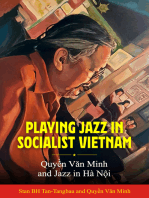

Figure 2. Kh?nh Ly on a 45 RPM record released in 1968 on which she and another

singer,Le Thu, sing four love songs by Trinh C?ng Son. This was a relatively rare release,

as record were too for most Vietnamese. The arrival of the cassette

players expensive

recorder facilitated the circulation of San s songs.

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

618 JohnC. Schafer

was very young. Unlike San, she does not appear to have been close to her

mother. She has described herself as an orphan, neglected and abandoned by

her family So she set out on her own, singing to make a

living,

with a little help from her friends. "I was searching," she has said of this

period inher life,"livinga vagabond lifesupportedby some kind friends:

one a friend would a little rice, the next

day give day another would give

me half a bottle of fish sauce. Poor but I wasn't sad because my

happy,

didn't treat me well, renounced me." (1988, 16)

family

When she was Ly married and was

Kh?nh as a Catholic.

eighteen, baptized

her husband, the manager of a radio station inD?lat, was understand

Apparently

at least she was able to travel and in

ing; perform with San Saigon and Hue

(NguyenThanh Ty 2004, 93). In a recent interview, mar

Kh?nh Ly calls her first

a mistake and says that, like her current husband, she has lived a life of

riage

several spouses and many lovers (2004, 82). Both San and Kh?nh Ly had no

fathers to guide them into adulthood. Their phenomenal success may be, in

a result of the freedom

part, they had: Their fathers might have insisted they

lead more conventional lives.

San and Kh?nh was

Lys easygoing, free relationship part of their appeal,

another cause of the Trinh C?ng San

contributing phenomenon. They

modeled a new kind of for young who were eager to break away

couple people

from rigid Confucian rules governing relations between the sexes. "They traveled

Tien observes, "and created the image of'a a a

together," Dang couple,' boy and

a natural

girl with and guiltless friendship that reminded young intellectuals of

Nh?t Linh'sfairly

recent novel D?i ban3 Like the couple in this novel they

had their native land, love, fate, duty to the country, and all the while 'Autumn

passes, winter's far away, summer brings clouds, and love's a flying bird against

the Kh?nh Ly, who speaks and writes in a

sky'"36 (2001b, 185). fairlymelodra

matic wrote of her with San in a 1989 article.37

style, movingly relationship

Asked about this article a year later, Son praised it but said that Kh?nh

Ly's

"heartfelt lines about him were for someone else, someone who has died.

Kh?nh Ly and I were just friends.

We loved each other as friends" (2001/1989,

215).

When Kh?nh Ly elected tomove to the United States in 1975 and San

decided to stay in Vietnam, their situation symbolized for many Vietnamese

the pain of separation, the sadness of exile. Around 1977-78, when the

3

named D?ng is in lovewith Loan, a

InDot han (TwoFriends), published in 1936, a revolutionary

modern woman who, with against the rigidities of a feudalistic Confucian

along D?ng, struggles

society.

Tien quotes lines from Son's song the Names of the Four Seasons."

36Dang "Calling

37Thisarticle ismentioned by L? Quynh in an interview

with Son (2001/1989,214).

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Trinh C?ng Scm Phenomenon 619

of Vietnamese San wrote a

number leaving by boat reached record levels, song

called "Do You Still Remember or Have You which

Forgotten?" begins,

Do or have you

you still remember forgotten

Saigon where the rain stops and it's sunny again,

suddenly

Old streets that know the names of passers

by,

Street lightson each sleepless night,

under the green dome of tamarind leaves?

Mornings

Do you still remember or have

you forgotten

The that you often visited no matter the season,

neighbors

The street that lies and listens for rain or for sun?

You are is the same,

gone but this place

Above the small streets the leaves are still green.

San and Kh?nh not lovers, but many

Ly may have been just very close friends,

Vietnamese believe that he wrote this song for her.

The Cassette Recorder

to Gibbs's definition, in theWest, music" is an urban

According "popular

music, usually market based, that is distributed by the mass media (Gibbs

1998b). Trinh Son was a in the sense that his music was

C?ng "popular" singer

modern and urban, but itwas not?at least until the "market

mid-1960s?really

nor was it "distributed the mass media." When the Trinh

based," by C?ng San

his songs were distributed on dittoed song sheets that Son

phenomenon began,

and Kh?nh Ly passed out at concerts. Other students would copy them into

their student notebooks. Later, more professionally printed collections appeared,

each one containing the words and music to around a dozen songs. When the war

escalated in 1964-65, American troops poured in, and with them came consumer

to boost South Vietnams

goods, part of the U.S. plan economy. Japanese Honda

and Akai and Sony tape recorders soon became

motorcycles readily available.

The first tape recorders to be used in Vietnam were the large reel-to-reel

variety, which the Vietnamese called (and still call) Akai, after the brand name.

These were cumbersome and expensive but were soon

replaced by much

more

convenient and considerably cheaper cassette tape recorders.

These developments led to a somewhat paradoxical situation: The same

American escalation of the war that had provoked Trinh C?ng San to write

antiwar also provided him with the means

songs for their distribution and

him a singer, in the American

sense of this

thereby helped make "popular"

term. records were available since French colonial times but were

Phonograph

never widely distributed in Vietnam, probably because they required

to Co southerners this song because itwas the first song after

38According Ngu, many appreciated

April 30, 1975, to referto theirbeloved largestcityas Saigon, notHo Chi Minh City (2001, 9-10).

Circulation of this song was forbidden, as I in the section to a New

explain "Adapting Regime."

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.86 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 22:46:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

620 JohnC. Schafer

to and because both the records and the

sophisticated technology produce

to them on were the means of all but the

phonograph play expensive?beyond

richest Vietnamese consumers. recorders, especially the cassette

Tape type,

however, could be purchased by the middle class. Cassette tapes, which could

easily be duplicated, became

an

important

means of distributing San s songs,

especially after the government banned them.

to circulate in South Vietnam, one had to

In