Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Causalgia A Review of Nerve Resection Amputation Immunotherapy and Amputated Limb Crps II Pathology

Uploaded by

punit lakraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Causalgia A Review of Nerve Resection Amputation Immunotherapy and Amputated Limb Crps II Pathology

Uploaded by

punit lakraCopyright:

Available Formats

The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences (2023), 1–6

doi:10.1017/cjn.2023.260

Original Article

Causalgia: A Review of Nerve Resection, Amputation,

Immunotherapy, and Amputated Limb CRPS II Pathology

C. Peter N. Watson1, Rajiv Midha2 and Denise W. Ng3

1

University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Section of Neurosurgery, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada and

3

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

ABSTRACT: Background: Causalgia and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II with nerve injury can be difficult to treat. Surgical

peripheral nerve denervation for causalgia has been largely abandoned by pain clinicians because of a perception that this may aggravate a

central component (anesthesia dolorosa). Methods: We selectively searched Pubmed, Cochrane, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, and

Scopus from 1947 for articles, books, and book chapters for evidence of surgical treatments (nerve resection and amputation) and treatment

related to autoimmunity and immune deficiency with CRPS. Results: Reviews were found for the treatment of causalgia or CRPS type II

(n = 6), causalgia relieved by nerve resection (n = 6), and causalgia and CRPS II treated by amputation (n = 8). Twelve reports were found of

autoimmunity with CRPS, one paper of these on associated immune deficiency and autoimmunity, and two were chosen for discussion

regarding treatment with immunoglobulin and one by plasma exchange. We document a report of a detailed and unique pathological

examination of a CRPS type II affected amputated limb and related successful treatment with immunoglobulin. Conclusions: Nerve resection,

with grafting, and relocation may relieve uncomplicated causalgia and CRPS type II in some patients in the long term. However, an

unrecognized and treatable immunological condition may underly some CRPS II cases and can lead to the ultimate failure of surgical

treatments.

RÉSUMÉ : Causalgie : une analyse de la résection nerveuse, de l’amputation, de l’immunothérapie et de la pathologie du SDRC de type II

du membre amputé. Contexte : La causalgie et le syndrome de douleur régionale complexe (SDRC) de type II avec lésion nerveuse peuvent

être difficiles à traiter. La dénervation chirurgicale des nerfs périphériques pour traiter la causalgie a été largement abandonnée par les

cliniciens de la douleur en raison de l’impression qu’elle peut aggraver une composante centrale (névralgie du trijumeau ou anesthesia

dolorosa). Méthodes : Nous avons effectué des recherches sélectives (à partir de 1947) dans PubMed, Cochrane, MEDLINE, Embase,

CINAHL Plus et Scopus pour trouver des articles, des livres et des chapitres de livres portant sur les traitements chirurgicaux (résection de

nerfs, amputation) et les traitements liés à l’auto-immunité et à la déficience immunitaire dans le cadre du SDRC. Résultats : Des analyses ont

été trouvées pour le traitement de la causalgie ou du SDRC de type II (n = 6), de la causalgie soulagée par résection nerveuse (n = 6) et de la

causalgie et du SDRC de type II traités par amputation (n = 8). Douze rapports portant sur l’auto-immunité en lien avec le SDRC ont été

identifiés, dont un article explorant le déficit immunitaire et l’auto-immunité associée ; deux ont été choisis pour la discussion concernant le

traitement par immunoglobuline et un autre en lien avec un traitement par échange de plasma. Nous voulons aussi présenter un rapport axé

sur l’examen pathologique détaillé et unique d’un membre amputé atteint de SDRC de type II et sur un traitement réussi à l’aide

d’immunoglobulines. Conclusions : La résection nerveuse avec greffe, de même que la relocalisation, peuvent soulager à long terme la

causalgie non compliquée et le SDRC de type II chez certains patients. Cependant, une condition immunologique non-détectée et traitable

peut être à l’origine de certains cas de SDRC de type II et conduire en dernier lieu à l’échec de traitements chirurgicaux.

Keywords: Causalgia; complex regional pain syndrome type II (CRPS II); surgical treatment; nerve resection/relocation; amputation

pathology; autoimmunity; immune deficiency; neuropathic pain (NeP); intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg); randomized controlled trial

(RCT); regenerative peripheral nerve interface (RPNI); targeted motor reinnervation (TMR)

(Received 9 January 2023; final revisions submitted 26 June 2023; date of acceptance 15 July 2023)

Corresponding author: C. Peter N. Watson; Email: peter.watson@utoronto.ca

Cite this article: Watson CPN, Midha R, and Ng DW. Causalgia: A Review of Nerve Resection, Amputation, Immunotherapy, and Amputated Limb CRPS II Pathology. The Canadian

Journal of Neurological Sciences, https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260

© The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution and reproduction, provided the original article is

properly cited.

https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260 Published online by Cambridge University Press

2 The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences

Introduction

Silas Weir Mitchell (1864)1 originally described the features of

causalgia and coined that term from his experience with nerve

injuries in the American Civil War as the burning neuropathic pain

(NeP) after traumatic nerve injury. When obvious traumatic nerve

injury pain is complicated by a number of other symptoms and

signs, it can be referred to as complex regional pain syndrome type

II with nerve injury (causalgia) (CRPS II) (Supplementary

Appendix A).2 We describe in the Results section abbreviated

examples of previously published cases3,4 to illustrate these two

forms of causalgia treated by neurectomy, as well as the surprising,

unpublished, long term, and follow-up of one of these patients.

Except for trigeminal neuralgia, surgical procedures such as nerve

resection and amputation for NeP such as causalgia aimed at

peripheral nervous system denervation are regarded by many, if not

most, of the community of thoughtful, experienced pain clinicians as

not helpful, particularly in the long term. This is probably in part

because of a perceived risk of aggravating a central component

(anesthesia dolorosa), and thus, these operations have been largely

abandoned.

In this article, we discuss mainly, but not exclusively, the pain

literature regarding nerve resection surgery and amputation for

causalgia. It is particularly critical to report results regarding the

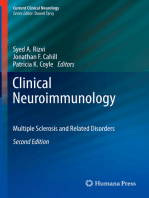

long-term efficacy and safety of any controversial, innovative, and Figure 1: HG: the leg on the morning of amputation.

especially initially successful procedures. We report, to our

knowledge, the unpublished, unique pathological examination of

an amputated limb from a previously reported patient surgically Where the term “CRPS” is used in discussing an article we mean

treated by nerve resection with CRPS type II (causalgia)4 with CRPS generally, as used in that particular article. We use CRPS I

pathological and serological evidence, suggesting an unrecognized and CRPS II when the article specifically stated that this is the

immunological disturbance (immune deficiency and autoimmun- subject of the article.

ity). These immune abnormalities influenced a subsequently An amputated limb (Figure 1) from a CRPS II causalgia patient4

successful medical treatment by immunotherapy with this (case 2 HG in the Results section here) was examined in detail by a

refractory patient. These conditions may account for treatment general pathologist (AF), dermatopathologists (KN, MS, and

failures in some patients with CRPS. We review in this article the MAD), and a neurosurgeon (RM) the latter with a special interest

evidence for immunological abnormalities and immunotherapy and experience with peripheral nerve surgery. Because of the

with causalgia but also CRPS generally and not exclusively CRPS II, pathological and serological findings, we also searched these

since the specific CRPS II literature is sparse and there are clinical databases for immune abnormalities (immune deficiency and

similarities between CRPS I and CRPS II. autoimmunity) and immunotherapy in patients with causalgia and

CRPS, CRPS I and CRPS II.

Methods

Results

A literature search from 1947 (Pubmed, Cochrane, MEDLINE,

EMBASE, and CINAHL Plus) was carried out for articles, reviews, No books or book chapters were found on the surgical treatment of

books, and book chapters regarding the surgical treatment of causalgia by nerve resection or amputation. Six reviews of the

causalgia and CRPS II (causalgia) by nerve resection and by treatment of CRPS were identified5–10 only one of which mentioned

amputation. We reviewed the surgical literature, but the focus was amputation.9 The comprehensive review of CRPS by Stephen Bruehl

mainly on the pain literature as it was thought more likely to be (2015)8 does not discuss nerve resection or amputation. Six cases and

precise regarding the terms causalgia and CRPS II. Although case series were located regarding nerve resection.3,4,11–14 Twelve

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard, from reports were located regarding the role of autoimmunity in CRPS,15–26

our previous studies we recognized that these were probably less and one of them about the association of autoantibodies with B cell

likely or unlikely and that most reports would be reviews or of cases immune deficiency.25 We discuss two of these articles17,18 on the

and case series. Thus, although the scope of this search was narrow treatment of CRPS with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and one

(restriction to the terms “causalgia,” “CRPS,” and “CRPS II” and to by plasma exchange.26 Eight cases or case series were found regarding

“nerve resection” and “amputation”), the search was also broad for amputation27–34 for causalgia and CRPS II. One of our published

a range of study types. patients4 had pathological evidence supporting autoimmunity,

Because of a need for diagnostic precision, there was the serological evidence of low immunoglobulins IgG and IgA, and

exclusion of publications using terms other than causalgia, CRPS, positive tests for an autoimmune process with positive anti-SSA and

and CRPS II (i.e., neuroma pain, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and anti-RO autoantibodies, despite other negative tests for autoimmune

deafferentation pain) as well as other interventions (i.e., disorders (e.g., negative ANA (antinuclear antibody) and anti-DNA

sympathectomy, dorsal root ganglion stimulation, dorsal column antibodies). In summary, there is in the literature some evidence for

stimulation, and motor cortex stimulation). the successful treatment of causalgia by nerve resection and

https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Le Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques 3

amputation; however, some failures of surgical treatment may be

accounted for by treatable underlying immune abnormalities.

We report here the previously unpublished, very long-term

follow-up of two previously published cases of causalgia treated

successfully initially by nerve resection as follows.

Case 1, CH3 uncomplicated causalgia

A 14-year-old male presented with a 14-month history of constant

right infraorbital, severe, burning pain, with electric shocks and

pain on dynamic touch (allodynia) due to intractable causalgia

after a fractured right orbit. He was housebound and refractory to

all analgesics. The infraorbital nerve was sectioned proximal to the

injury, grafted, and relocated into the buccal fat pad. He was able to

return to school and a normal life and has been pain-free for

19 years.

Case 2, HG4 CRPS type II causalgia (with nerve injury)

A 19-year-old female was seen with a 13-year history of intractable

CRPS type II after a left leg injury. The superficial peroneal and

sural nerves were resected. Successful relief lasted for 4 years and 4

months. Unfortunately, incipient left leg gangrene (Figure 1) and

the return of the severe left leg pain at 4 years and 4 months

required amputation. The pathological examination of the

amputated limb plus additional blood tests led to a successful

immunotherapy at 3 years follow-up. The pathological findings in

our patient4 suggested autoimmunity and serology B cell

immunodeficiency. Following amputation, her skin lesions became

extensive and spread to hair, ears, and mouth, and she was unable

to wear a prosthesis and was reclusive and bedridden with stump

and phantom pain. She continued to have frequent upper Figure 2: HG: 2 years after treatment with immune globulin HG was able to wear her

prosthesis, and walk, had a reduction in the need for strong analgesics, no longer had

respiratory infections and episodes of bronchitis and pneumonia

frequent upper respiratory infections and pneumonia and had marked improvement

for over 2 years and 4 months. Because of her immunological status in her generalized skin lesions (at 3 years after amputation she continued with marked

(immune deficiency and autoimmunity), she was commenced on improvement and only scarring at the sites of her previous generalized skin rash).

once weekly subcutaneous human immune globulin 20% solution.

After 2 years, she stated that there was a “huge difference”; in that

she could use her prosthesis full time, no longer required strong On the general pathological examination (by AF) in addition to

analgesics, no longer had frequent respiratory infections, and her the extensive ulceration of the skin, there was evidence of

skin lesions improved markedly (Figure 2). At 3 years (March underlying vascular abnormalities, with the presence of venous

2023) follow-up, her skin lesions only remained as scars. At this thrombosis and chronic changes in the cutaneous and subcuta-

time, HG stated “I feel so much better I will happily do this (have neous small vessels. Associated chronic changes were seen with

the immunotherapy) for the rest of my life.” dermal and pannicular fibrosis and calcification.

The case was reviewed in consultation with dermatopathology

(KN, MS, and MD), and the pathology addendum report findings

The unique, previously unreported pathological examination were that the vascular changes were thought to be possibly due to a

of the lower limb from the amputation on December 4, 2017 vasculopathic process. Potential etiologies suggested included anti-

carried out on HG (case 2). phospholipid antibody syndrome, lupus, and others, but diagnostic

Howard et al.38 carried out a meta-analysis and validation of a features were not seen. The findings reported could also be associated

histopathology scoring system for amputations for CRPS in 22 with Behcet’s disease. None of the above specific pathologies was

patients. They concluded that for various reasons (infrequent found. Repeated blood work after amputation found a normal or

reporting of diagnostic criteria, lack of routine stains, and lack of negative erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein

clinical pathological correlation) that “it is quite difficult to write a (CRP), ANA, anti-DNA antibodies, lupus inhibitors, antiphospho-

meaningful systematic review of CRPS histology at this time.” The lipid, and anti-cardiolipid antibodies, but anti-SSA/Ro autoantibodies

strengths of our amputated limb pathology (HG, case 2) are with were positive. HG was found to have B cell deficiency on repeated

the clinical features, diagnostic precision, surgical details, testing (IgG 2.25 and 3.34, range 6.8–18.0; IgA 0.06 and 0.07, range

laboratory and pathological findings, and very long-term follow- 0.6–4.20, with normal IgM x2).

up. The amputated leg (preoperatively in Figure 1) of our patient Additionally, the frozen limb was dissected shortly after the

(case 2 HG) with CRPS type II was examined by three different amputation on December 4, 2017 by a neurosurgeon (RM) with a

specialists (general pathology, dermatopathology, and neurosur- special interest in peripheral nerve surgery and nerve pathology. No

gery) in order to determine any possible cause pathologically for obvious neuromas were found at the sites of the implantation of the

the deterioration in the patient’s condition. nerves. All the nerve specimens of the leg appeared normal on

https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260 Published online by Cambridge University Press

4 The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences

microscopy. The lack of neuroma formation is supportive evidence (RPNI) (Santosa et al 2021).35 Alternatively, the proximal stump of

that the original nerve resection operation was successful and had the injured nerve after neuroma resection is micro-surgically

prevented neuroma formation. This evidence supports the prolonged repaired to an adjacent small muscle nerve, a procedure termed

relief (4 years and 4 months) resulting after nerve resection. targeted motor reinnervation (TMR) (Janes et al 2021).36 Both of

these procedures seemingly have improved pain outcomes in

patients with new or recurrent neuromas, as compared to historical

Discussion case series, although studies comparing the two methods are still

Neurectomy lacking. The efficacy of TMR for managing CRPS II is being

explored, and a small case series (Shin et al., 2022) shows

With regard to nerve resection surgery for causalgia, Silas Weir promising results.37

Mitchell (1872) documented causalgia in a civil war soldier (case

47, page 292),11 and the effects of resecting the median nerve with

Autoimmunity and immunotherapy

an initial aggravation of the pain, and then moderation in the

distribution of the resected nerve. However, the pain persisted Twelve references were found regarding autoimmunity associated

severely in another (ulnar) nerve’s territory. with CRPS.15–26 Eight of these references are to research, suggesting

Noordenbos and Wall (1981)12 reported seven patients with autoimmunity in CRPS against nervous system targets in humans

severe causalgia with long-term follow-up unrelieved by resection. and in animal research. One reference25 found autoimmunity

This article by two highly respected authors in the field of pain may associated with immunodeficiency (B cell deficiency) caused by

have contributed to a negative view of this form of treatment as protein kinase C delta, but it is unknown how often this

there is a general view in the community of pain physicians and combination of immunological findings occurs in patients with

surgeons that further denervation (other than in trigeminal CRPS II or other NeP as with HG (our case 2 in Results). Two

neuralgia) does not generally help NeP such as causalgia and runs reports stated that some patients responded to treatment with

the risk of aggravating a central component (anesthesia dolorosa). immunoglobulin.17,18 Blaes et al (2004)17 commented on “some”

Only a few other reports of nerve resection surgery for causalgia uncontrolled cases of theirs and of others with improvement by

and CRPS II have appeared in the pain literature in the past three IVIg. Goebel et al (2017)18 reported that a parallel design, RCT of

decades. Inada et al (2005)13 reported two cases of the successful 108 eligible patients with moderate to severe CRPS of 1–5 years

surgical relief of upper extremity causalgia (digital nerve injury) by duration in which two doses of low dose (0.5 g/kgm of body

nerve resection. Follow-up was 2 years in one patient and weight) of IVIg separated by 6 weeks was not effective in relieving

30 months in the other. Watson et al (2007)3 (see abbreviated case 1 moderate/severe CRPS of 1–5 years duration. They referred to

CH in the Results section) reported a 19-year-old male with severe, their previous open cases and a small RCT of low-dose IVIg which,

intractable right infraorbital nerve causalgia after a fractured right in both studies, showed that 25% had “profound pain relief of

orbit. Thirteen months after injury, the pain remained severe and greater than 50%.” They discussed 5 other reports of CRPS one

intractable and the nerve was resected proximal to the fracture, with high dose (2 g/kgm) IVIg for a total of 25 patients which

grafted and placed in the buccal fat pad with immediate relief. indicated efficacy. They stated that “in addition, other authors have

Long-term follow-up after publication found that he has been indicated that they have been using IVIg successfully in their

pain-free for 19 years. Stovkis et al (2010)14 reported 34 patients patients.” Goebel et al., (2017) further said that “it is not known

operated on for “neuroma pain” (but which included CRPS II) by why the results from the current RCT differ so markedly from

nerve resection and relocation. Postoperative satisfaction rates those of earlier studies.” Why are these results inconsistent?

were 36% (4/11) with CRPS II patients and 65% 15/23 in non- Perhaps only one type of CRPS may respond (only CRPS I or CRPS

CRPS patients. Watson et al (2014)4 (case 2 HG in the Results II). It may be that a full dose (2 g/kgm) could be required and/or a

section) reported a 19-year-old female, with successful relief by shorter dosing interval.

nerve resection for 4 years and 4 months after 13 years of In our patient with CRPS II (case 2 HG in Results), successful

intractable (CRPS) type II (causalgia) affecting the peroneal and treatment was with 3 years of a weekly infusion of subcutaneous

sural nerves of the left leg. Severe leg pain recurred and incipient human immune globulin 20% solution. One retrospective study

gangrene (Figure 1) required amputation (unpublished long-term found that of 34 patients with CRPS who received plasma exchange

follow-up in the Results section). The pathological examination of therapy, 91% reported a significant reduction in pain, with 45%

the amputated limb (see Results section) suggested autoimmunity having sustained pain relief with additional weekly treatments.26

and serological testing revealed B cell deficiency as well as Sahbaie et al. (2022)39 studied a mouse model of CRPS, which may

autoimmunity. She responded to immunotherapy, was markedly have some relevance to the human condition; in that they found

better at 2 years follow-up (Figure 2) and is pain-free at 3 years that modulation of autonomic activity after limb injury may limit

post-amputation. pain-supporting autoantibodies and may reduce chronic pain

Nerve grafting, entubalation, and relocation of the proximal which may be relevant to our human patient (case 2 HG).4 The role

nerve stump after neuroma resection often lead to a favorable of immunodeficiency and/or autoantibodies as cause or effect is

outcome, as reported in the literature and anecdotally based on the unclear. Although it is possible that the amputation itself resulted

experience of one of us (RM). In recent years, the surgical in improvement, the marked, but persistent improvement in pain

management of painful neuromas, where nerve grafts are not and function in our patient4 did not occur until soon after the

possible, has evolved to provide a more suitable environment for immunotherapy was started. The most dramatic features were that

axons to reside or grow and not reform a painful neuroma. After HG became able to wear her prosthesis, walk using it, had no need

neuroma resection, instead of burying the proximal stump of an for strong analgesics, experienced a lack of respiratory infections,

injured nerve into an innervated muscle, the nerve is placed and and as well had marked improvement of her generalized skin

sutured within a freshly harvested small piece of (denervated) lesions (Figure 2) at 2 years and only skin scars at 3 years follow-up

muscle, a technique termed regenerative peripheral nerve interface (see Results section).

https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Le Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques 5

Amputation Summary

5–10

Of six reviews of the treatment of CRPS, only one specifically

referenced amputation for CRPS II.9 Two reviews of amputation 1. Causalgia and complex regional pain syndromes types I and II

for causalgia were found.27,34 Bodde et al., 201127 reviewed 26 (causalgia) are poorly understood and difficult to treat, but both

studies of amputation for CRPS with Level IV evidence concluding may be neuropathic and traumatic in origin.

that whether to amputate or not for intractable CRPS was “an 2. Because of the clinical similarities between CRPS types I and II,

unanswered question.” Ayyaswamy et al (2019)34 reported a it is plausible that a successful treatment for CRPS type II may

systematic review of 11 studies of quality of life (QOL) after be applicable to both conditions.

amputation for intractable CRPS with a total of 96 patients and 107 3. Nerve transection and amputation have been reserved in the

amputations finding that 66/107(62%) had improvement in QOL past for medically intractable cases of CRPS II and may result in

regarding functional status and general health. They concluded benefit in some patients. Nerve resection may be more

that amputation could be considered to improve QOL but successful with nerve grafting, relocation, and the novel surgical

considered that the evidence was limited with risk of CRPS approaches described and referenced in this article.

recurrence and of phantom limb pain. Other papers regarding 4. There is a small inconsistent literature on autoimmunity and

amputation included cases and case series, but none of these immunotherapy with CRPS generally (CRPS I and II).

specified the type of CRPS. However, we decided to review these 5. Surgical and other treatment failures may be, in some instances,

articles regardless because of the similarities between CRPS I and II a result of an unrecognized but treatable, underlying immuno-

and because of the lack of such data in the latter. Midbari and logical condition (autoimmunity and immune deficiency).

Eisenberg (2017)32 commented that none of the published papers

Supplementary material. The supplementary material for this article can be

on amputation for CRPS had been published in the pain literature,

found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260.

and that the issue was the reluctance of the pain medicine

community to consider amputation for intractable patients. The Acknowledgments. Dr A Franko (AF) carried out the general pathological

recent literature on amputation for CRPS consisted of single-case examination. Dermatopathology examination was carried out by Dr K Naert

reports30,33 and case series.29,32 One case report by Goebel (2018)33 (KN), Dr M Schneider (MS), and Dr M Abdi Daoud (MD). The assistance of Dr

described recurrence of pain 2 years after amputation. Kashy et al30 Judy Watt Watson and Emily Watson has been invaluable in the preparation of

reported a successful outcome in a patient with CRPS I but this manuscript.

provided no long-term data. In one case series, Krans-Schreuder

Statement of authorship. CPNW collected the data and wrote the

(2012)28 reported that 18/21 patients said they would recommend manuscript. RM examined the amputated limb regarding the nerves from

amputation to other patients with CRPS I. Midbari et al 201631 the previous nerve resection/relocation surgery. RM and DWN revised the

reported consistently better results with CRPS in an amputated manuscript for intellectual content, and all authors approved the final

group of 19 patients versus 19 control unamputated patients and manuscript.

stated that 13/19 of the amputated group said they would

recommend the operation to other intractable CRPS patients. Competing interests. The authors have no conflicts and nothing to disclose.

Specifically, there are no other non-author contributions, no technical help, no

Strengths of this review are that we gather in one location some

financial or material support, or financial arrangements needing to be disclosed.

otherwise disparate information for clinicians regarding nerve

resection and amputation for medically intractable CRPS II

(causalgia). These data provide some guidance regarding these References

possible surgical options in some of these refractory patients. We 1. Mitchell SW, Morehouse GJ, Keen WK. Gunshot wounds and other injuries

also describe the first detailed pathology of an amputated limb of nerves. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1864.

from a patient with CRPS type II which led to a successful 2. Harden R, Bruehl S, Perez R, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria

treatment related to immune abnormalities. Limitations of this (The "Budapest Criteria") for complex regional pain syndrome. PAIN.

review are that some reports of the surgical procedures for 2010;150:268–74.

peripheral nerve injury pain may have been deliberately excluded 3. Watson CPN, Stinson JN, Dostrovsky JO, Hawkins C, Rutka J, Forrest C.

as no concise terms, methods, or outcomes were discussed. Nerve resection and relocation may relieve causalgia. A case report. PAIN.

2007;132:211–7.

In conclusion, surgery involving nerve resection and reloca-

4. Watson CPN, Mackinnon SE, Dostrovsky JO, Bennett J, Faran RP, Carlson

tion by grafting, if necessary, may be more successful in

T. Nerve resection, crush and relocation relieve complex regional pain

uncomplicated causalgia3 (case 1 CH in Results) involving a syndrome type II (causalgia): a case report. PAIN. 2014;155:1168–73.

traumatic injury to a single sensory nerve accessible proximal to 5. Hord AL, Oaklander AL. Complex regional pain syndrome: a review of

the injury. A surgeon skilled in nerve reconstruction and familiar evidence-supported treatment options. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003;7:

with the techniques described in a previous article4 is essential in 188–96.

the authors’ view. Although there is a small literature on the effect 6. Tran DHQ, Duong S, Bertini P, Finlayson RJ. Treatment of complex

of amputation for CRPS generally, there are no good data to guide regional pain syndrome: a review of the evidence. Can J Anesth. 2010;57:

a decision regarding this. Surgery alone may be less beneficial for 149–216.

CRPS type II, such as with HG our case4 with an unrecognized, 7. O’Connell B, Wand M, McAuley J, Marston L, Mosley GL. Cochrane

database of systematic reviews: interventions for treating pain and disability

underlying but treatable condition (immune deficiency and

in adults with complex regional pain syndrome – an overview of systematic

autoimmunity) which may yield only temporarily positive results

reviews. 2013. https:\\www.cochranelibrary.com.

after nerve resection surgery. Caution is necessary in extrapo- 8. Bruehl S. Complex regional pain syndrome. BMJ. 2015;361:h2730.

lating from a single case treated successfully by immunotherapy 9. Duong SD, Bravo Todd KJ, Finlayson RJ, Tran DQ. –Treatment of complex

such as our patient HG case 2 (see Results section)4 with regional pain syndrome: updated systematic review and narrative. Can J

intractable CRPS II (causalgia). Anesth. 2018;65:658–84.

https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260 Published online by Cambridge University Press

6 The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences

10. Taylor S, Noor N, Urits I, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: a 26. Alexander GM, Aradillas E, Schwarzman RJ, et al. Retrospective study of

comprehensive review. Pain Ther. 2021;10:875–92. plasma exchange therapy in patients with complex regional pain syndrome.

11. Mitchell SW. Injuries to nerves and their consequences. Philadelphia: JB Pain Physician. 2015;18:383–94.

Lippincott; 1872. 27. Bodde MI, Dijkstra PU, den Dunnen WFA, et al. Therapy-resistant

12. Noordenbos W, Wall PD. Implications of the failure of nerve resection and complex regional pain syndrome: to amputate or not? Bone Joint Surg.

graft to cure chronic pain produced by nerve lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg 2011, 1799–1805.

Psychiatry. 1981;44:1068–73. 28. Krans-Schreuder HK, Bodde M, Chrier E, Dijkstra P, et al. Amputation for

13. Inada Y, Morimoto S, Moroi K, Endo K, Nakamura T. Surgical relief of long standing therapy-resistant type 1 complex regional pain syndrome.

causalgia by an artificial nerve tube graft: successful surgical treatment of Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2012;94:226–8.

causalgia by in situ tissue engineering with a polyglycolic acid-collagen tube. 29. Bodde MI, Chrier E, Krans HK, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU. Resilience in

PAIN. 2005;117:251–18. patients with amputation because of complex regional pain syndrome type

14. Stovkis A, van der Avoort DJ, Van Neck JW, Hovius SE, Coert JH. Surgical I. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:838–43.

management of neuroma pain: a prospective follow-up study. PAIN. 30. Kashy K, Abd-Elsayed AA, Farag E, et al. Amputation is an unusual

2010;151:862–9. treatment for therapy-resistance complex regional pain syndrome type I.

15. Blaes F, Schmitz M, Tschernatsch M, et al. Autoimmune etiology of complex J Ochsner. 2015;15:441–42.

regional pain syndrome. Neurology. 2004;63:1734–6. 31. Midbari A, Suzan E, Adler T, et al. Amputation in patients with complex

16. Goebel A, Vogel O, Caneris O, et al. Immune responses to Campylobacter regional pain syndrome: comparative study between amputees and non-

and serum antibodies in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. amputees with intractable disease. Bone Joint J. 2016;98 B:548–54.

J Neuroimmunol. 2005;162:184–9. 32. Midbari A, Eisenberg E. Is the pain medicine community reluctant to

17. Blaes F, Tschernatsch M, Braeburn ME, et al. Autoimmunity in complex discuss limb amputation in patients with intractable complex regional pain

regional pain syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1107:168–73. syndrome? Pain Med. 2017;18:1406–7.

18. Goebel A, Bisla J, Carganillo C, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin 33. Goebel A, Lewis SR, Phillip R, Sharma M. Dorsal ganglion stimulation for

treatment for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome. complex regional pain syndrome: recurrence after amputation for CRPS and

A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:476–83. failure of conventional spinal cord stimulation. Pain Pract. 2018;18:104–8.

19. Goebel A, Blaes F. Complex regional pain syndrome, prototype of a novel 34. Ayyaswamy B, Saeed B, Anand A, Chan L Shetty V. Quality of life after

kind of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:682–6. amputation in patients with complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic

20. Dirckx M, Schreiers MW, deMos M, et al. The prevalence of autoantibodies review. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:533–40.

in complex regional pain syndrome type I. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2:1–5. 35. Santosa KB, Oliver HD, Cederna PS, Kung TA. Regenerative peripheral

21. Cuhadar U, Gentry C, Vastani N. Autoantibodies produce pain in nerve interfaces for prevention and treatment of neuromas. Clin Plast Surg.

complex regional pain syndrome by sensitizing nociceptors. PAIN. 2020;47:311–21.

2019;160:2855–65. 36. Janes LE, Fracol LE, Dumanian GA, Ko JH. Targeted muscle reintegration

22. David Clark J, Tawfik VL, Tajerian M, Kingery WS. Autoinflammatory and for the treatment of neuroma. Hand Clin. 2020;37:345–59.

autoimmune contributions to complex regional pain syndrome. Mol Pain. 37. Shin SE, Haffner ZK, Chang BL, Kleiber GM. A pilot investigation

2018;14:174480691879912. DOI: 10.1177/1744806918799127. into targeted muscle reinnervation for complex regional pain syndrome,

23. Dubuis E, Thompson V, Leite MI, et al. Long-standing complex regional Type II. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e4718. DOI: 10.1097/

pain syndrome is associated with activating autoantibodies against alpha-1a GOX000000000004718.

adrenoreceptors. PAIN. 2014;155:2408–17. 38. Howard EL, Singleton M, Soulakvslidze I. Amputation for complex regional

24. Kohr D, Singh P, Tschernatsch M, et al. Autoimmunity against the beta 2 pain syndrome: meta-analysis and validation of a histopathology scoring

adrenergic receptor and muscarinicn-2 receptor in complex regional pain system. Pain Med. 2022, 1–17.

syndrome. PAIN. 2011;152:2690–700. 39. Sahbaie P, Li WW, Guo TZ, Kingery WS, Clark JD. Autonomic regulation of

25. Salzer E, Santos-Valente E, Klaver S, et al. B cell deficiency and severe nociceptive and immunologic changes in a mouse model of complex

autoimmunity caused by protein kinase C delta. Blood. 2013;121:3112–6. regional pain syndrome. J Pain. 2022;23:472–86.

https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2023.260 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- Clinical Neuroimmunology: Multiple Sclerosis and Related DisordersFrom EverandClinical Neuroimmunology: Multiple Sclerosis and Related DisordersNo ratings yet

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Narrative Review For The Practising ClinicianDocument10 pagesComplex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Narrative Review For The Practising ClinicianAlfath ZulfaNo ratings yet

- NERVE CONDUCTION STUDIES: ESSENTIALS AND PITFALLS IN PRACTICEpdfDocument9 pagesNERVE CONDUCTION STUDIES: ESSENTIALS AND PITFALLS IN PRACTICEpdfEduardo BessoloNo ratings yet

- Nerve Conduction StudiesDocument10 pagesNerve Conduction StudiesRyanNo ratings yet

- Painreports 2 E624Document8 pagesPainreports 2 E624Alfath ZulfaNo ratings yet

- 23499780Document8 pages23499780ginamilena90No ratings yet

- J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005 Mallik Ii23 31Document10 pagesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005 Mallik Ii23 31أحمد عطيةNo ratings yet

- Pathologic Basis of Lumbar Radicular Pain: BackgroundDocument8 pagesPathologic Basis of Lumbar Radicular Pain: BackgroundVizaNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Coexistence of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Neurofibromatosis Type 1Document4 pagesCase Report: Coexistence of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Neurofibromatosis Type 1Lupita Mora LobacoNo ratings yet

- 2013 The Double Crush SyndromeDocument6 pages2013 The Double Crush SyndromeDimitris RodriguezNo ratings yet

- RJR - 2019 - 3 - Art-02 - CRISTINA GOFITA - CRPS DIAGNOSISDocument8 pagesRJR - 2019 - 3 - Art-02 - CRISTINA GOFITA - CRPS DIAGNOSISmihail.boldeanuNo ratings yet

- Spec MRI Distinguish Acue TM of NMOSD N Infarction. Kister Et Al 2015Document21 pagesSpec MRI Distinguish Acue TM of NMOSD N Infarction. Kister Et Al 2015Ido BramantyaNo ratings yet

- Biomedicines 11 00044 v3Document19 pagesBiomedicines 11 00044 v3mariel gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Clin Exp Pharma Physio - 2008 - Gibbs - UNRAVELLING THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME FOCUS ONDocument8 pagesClin Exp Pharma Physio - 2008 - Gibbs - UNRAVELLING THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME FOCUS ONkotraeNo ratings yet

- Carpel Tunnel Syn EpsDocument12 pagesCarpel Tunnel Syn EpsKota AnuroopNo ratings yet

- JurnallDocument6 pagesJurnallThe MouzainNo ratings yet

- Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating PolyradiculoneuropathDocument13 pagesChronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathrafael rocha novaesNo ratings yet

- Complex Regional PainDocument8 pagesComplex Regional PainJuliana FeronNo ratings yet

- Compartement SyndromeDocument6 pagesCompartement SyndromeAnna ApsariNo ratings yet

- Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I - A Comprehensive Review. - 2015-Bussa-Acta-AnaesthesiologicDocument13 pagesComplex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I - A Comprehensive Review. - 2015-Bussa-Acta-Anaesthesiologicgeschrich7No ratings yet

- Clinical Approach To The Weak Patient in The IntensiveDocument18 pagesClinical Approach To The Weak Patient in The Intensivegstam69No ratings yet

- 2017 Article 1793Document5 pages2017 Article 1793annisaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CRPSDocument4 pagesJurnal CRPSPutu Alen RenaldoNo ratings yet

- Clinical/Scientific Notes: The Risk of Abducens Palsy After Diagnostic Lumbar PunctureDocument7 pagesClinical/Scientific Notes: The Risk of Abducens Palsy After Diagnostic Lumbar PunctureRafiq EsufzaeNo ratings yet

- Syringomyelia in Neuromyelitis Optica Seropositive For Aquaporin-4 Antibody: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesSyringomyelia in Neuromyelitis Optica Seropositive For Aquaporin-4 Antibody: A Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Neurologic Involvement in Scleroderma, A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesNeurologic Involvement in Scleroderma, A Systematic ReviewIsa RahmatikawatiNo ratings yet

- Calcified Pseudoneoplasm of The Neuraxis Capnon A Lesson Learnt From A Rare Entity PDFDocument3 pagesCalcified Pseudoneoplasm of The Neuraxis Capnon A Lesson Learnt From A Rare Entity PDFKisspetre PetreNo ratings yet

- Original Reports: Characterization of Hyperacute Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord Injury: A Prospective StudyDocument9 pagesOriginal Reports: Characterization of Hyperacute Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord Injury: A Prospective Studyezequiel zaragoza juarezNo ratings yet

- Incidental Complex Repetitive Discharges On Needle ElectromyographyDocument4 pagesIncidental Complex Repetitive Discharges On Needle Electromyographyfulgencio garciaNo ratings yet

- Neurological Disease in Lupus: Toward A Personalized Medicine ApproachDocument12 pagesNeurological Disease in Lupus: Toward A Personalized Medicine ApproachjerejerejereNo ratings yet

- Mejrh 134171Document9 pagesMejrh 134171Amazonia clinicaNo ratings yet

- Imaging in EncephalitisDocument10 pagesImaging in Encephalitisrafael rocha novaesNo ratings yet

- A Review of Lumbar Radiculopathy, Diagnosis, and TreatmentDocument7 pagesA Review of Lumbar Radiculopathy, Diagnosis, and TreatmentZuraidaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1878875018300159 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S1878875018300159 MainAlexandreNo ratings yet

- Encefalitis AutoinmuneDocument18 pagesEncefalitis AutoinmunealmarazneurologiaNo ratings yet

- Descarga Repetivia 2Document4 pagesDescarga Repetivia 2fulgencio garciaNo ratings yet

- Npab 002Document13 pagesNpab 002Muhammad Imran MirzaNo ratings yet

- Review of CimDocument8 pagesReview of CimMuhammad Imran MirzaNo ratings yet

- Antibodies and Neuronal Autoimmune Disorders of The CNS: Ó Springer-Verlag 2009Document9 pagesAntibodies and Neuronal Autoimmune Disorders of The CNS: Ó Springer-Verlag 2009deadcorpsesNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Contrast-Induced Encephalopathy Following Cerebral Angiography in A Hemodialysis PatientDocument4 pagesCase Report: Contrast-Induced Encephalopathy Following Cerebral Angiography in A Hemodialysis PatientAnaNo ratings yet

- The Spectrum of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A ReviewDocument11 pagesThe Spectrum of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A ReviewKomangNo ratings yet

- Muscular Weakness and Muscle Wasting in The Critically IllDocument14 pagesMuscular Weakness and Muscle Wasting in The Critically IllpamelaNo ratings yet

- Brainstem CysticercoseDocument4 pagesBrainstem CysticercoseDr. R. SANKAR CITNo ratings yet

- A Review of Lumbar Radiculopathy, Diagnosis, and TreatmentDocument7 pagesA Review of Lumbar Radiculopathy, Diagnosis, and TreatmentMatthew PhillipsNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Manifestations of Critical Illness: Invited ReviewDocument24 pagesNeuromuscular Manifestations of Critical Illness: Invited ReviewSebastián GallegosNo ratings yet

- Clinical Picture: Nocardia Brain AbscessDocument2 pagesClinical Picture: Nocardia Brain AbscesslathifatulNo ratings yet

- Nerve Entrapment - UpdateDocument17 pagesNerve Entrapment - UpdatealobrienNo ratings yet

- Brachial NeuritisDocument7 pagesBrachial Neuritisfirza yoga baskoroNo ratings yet

- Milne (2022) - Neuromonitoring and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Cardiac SurgeryDocument16 pagesMilne (2022) - Neuromonitoring and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Cardiac SurgeryVanessaNo ratings yet

- Phantom Limb Pain and Painful NeuromaDocument9 pagesPhantom Limb Pain and Painful Neuromaalex1973maNo ratings yet

- MRI SeizuresDocument7 pagesMRI SeizuresMarco MalagaNo ratings yet

- Potential Role of Stem Cells For Neuropathic Pain DisordersDocument5 pagesPotential Role of Stem Cells For Neuropathic Pain Disordersmatheus derocoNo ratings yet

- Pattern and Categorisation of Neurosurgical Emergencies: Conference ProceedingDocument3 pagesPattern and Categorisation of Neurosurgical Emergencies: Conference ProceedingarshadNo ratings yet

- Cranial CT in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome:: Spectrum of Diseases and Optimal Contrast Enhancement TechniqueDocument12 pagesCranial CT in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome:: Spectrum of Diseases and Optimal Contrast Enhancement Techniqueudayana kramasanjayaNo ratings yet

- Pain Practice - 2010 - Van Eijs - 16 Complex Regional Pain SyndromeDocument18 pagesPain Practice - 2010 - Van Eijs - 16 Complex Regional Pain SyndromeZuraidaNo ratings yet

- Spinal Epidural Cavernous Hemangiomas in The 2024 International Journal of SDocument3 pagesSpinal Epidural Cavernous Hemangiomas in The 2024 International Journal of SRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- The Diagnostic Relationship With Clinical and Neuroimaging Studies of Patients With Back PainDocument5 pagesThe Diagnostic Relationship With Clinical and Neuroimaging Studies of Patients With Back PainCentral Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- Review: Myasthenic CrisisDocument11 pagesReview: Myasthenic CrisisRaisha TriasariNo ratings yet

- Cei0121 0270Document5 pagesCei0121 0270Nur WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Proximal Radial Compression Neuropathy: Brian Rinker, MD, Charles R. Effron, MD, and Robert W. Beasley, MDDocument7 pagesProximal Radial Compression Neuropathy: Brian Rinker, MD, Charles R. Effron, MD, and Robert W. Beasley, MDRod VRNo ratings yet

- GMP, Haccp, KPDocument27 pagesGMP, Haccp, KPannaNo ratings yet

- Job Announcement-NewDocument31 pagesJob Announcement-NewErick MkomwaNo ratings yet

- Canadian Diabetes Clinical Guidelines 2008Document215 pagesCanadian Diabetes Clinical Guidelines 2008FelipeOrtiz100% (4)

- Danger Signs in NewbornDocument22 pagesDanger Signs in NewbornAbhirup BoseNo ratings yet

- New Resources For Nutrition Educators: Book Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease PreventionDocument2 pagesNew Resources For Nutrition Educators: Book Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention林艾利No ratings yet

- Fundamentals of NursingDocument5 pagesFundamentals of NursingLance Sta AnaNo ratings yet

- Report IndexedDocument302 pagesReport Indexeditab45No ratings yet

- Students Worksheet LabelDocument8 pagesStudents Worksheet Labeldina karsikaNo ratings yet

- AtlsDocument23 pagesAtlsvivi chanNo ratings yet

- Terminalia ArjunaDocument2 pagesTerminalia ArjunaSwapnil YadavNo ratings yet

- Ich GuidelinesDocument24 pagesIch GuidelinesJethava HathisinhNo ratings yet

- ASD Intervention - Akshaya R S and Sriram MDocument46 pagesASD Intervention - Akshaya R S and Sriram MSriram ManikantanNo ratings yet

- 1151 3608 1 PBDocument7 pages1151 3608 1 PBNilam SariNo ratings yet

- TrentalDocument4 pagesTrentalMaged AmerNo ratings yet

- Learning ContentDocument11 pagesLearning ContentRegilyn Montero Arevalo100% (1)

- 9780702072987-Book ChapterDocument2 pages9780702072987-Book ChaptervisiniNo ratings yet

- Immune Tolerance and Slow-Virus Disease: Skeletons in The Closet of Western Science & Public Health, by A. W. FinneganDocument38 pagesImmune Tolerance and Slow-Virus Disease: Skeletons in The Closet of Western Science & Public Health, by A. W. FinneganOperation OpenscriptNo ratings yet

- FlubioDocument6 pagesFlubiosaidaa hasanahNo ratings yet

- Malt Extract Italia MsdsDocument6 pagesMalt Extract Italia MsdsSorin LazarNo ratings yet

- Gordon's Functional Health PatternDocument12 pagesGordon's Functional Health PatternLoyloy D Man100% (1)

- Understanding Social Welfare A Search For Social Justice Ebook PDF VersionDocument62 pagesUnderstanding Social Welfare A Search For Social Justice Ebook PDF Versionjames.crandle290100% (40)

- Albert Loren Rhoton JRDocument30 pagesAlbert Loren Rhoton JRNestian ElenaNo ratings yet

- Microbiome - Hệ Vi Sinh Vật Trong Cơ Thể Người- wed HarvardDocument15 pagesMicrobiome - Hệ Vi Sinh Vật Trong Cơ Thể Người- wed HarvardNam NguyenHoangNo ratings yet

- Welcome To DOSH MalaysiaDocument25 pagesWelcome To DOSH MalaysiaMohammad Lui Juhari100% (1)

- 5 Polypharmacy Case StudyDocument6 pages5 Polypharmacy Case Studyapi-392216729No ratings yet

- Surgical Nutrition: Vic V.Vernenkar, D.O. St. Barnabas Hospital Dept. of SurgeryDocument54 pagesSurgical Nutrition: Vic V.Vernenkar, D.O. St. Barnabas Hospital Dept. of SurgeryAmir SharifNo ratings yet

- Two GUARANTEED Ways To ProfoundlyDocument12 pagesTwo GUARANTEED Ways To Profoundlycolderas jethNo ratings yet

- Stage One Application Form and Guide: International Communities ProgrammeDocument51 pagesStage One Application Form and Guide: International Communities ProgrammeRaj GildaNo ratings yet

- Plasma Pen - Consultation & Consent FormDocument10 pagesPlasma Pen - Consultation & Consent FormDS Hz Vega100% (1)

- Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma - Fonseca - Primary ManagementDocument7 pagesOral and Maxillofacial Trauma - Fonseca - Primary ManagementyogeshNo ratings yet

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (84)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- The Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeFrom EverandThe Twentysomething Treatment: A Revolutionary Remedy for an Uncertain AgeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (39)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (267)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- I Shouldn't Feel This Way: Name What’s Hard, Tame Your Guilt, and Transform Self-Sabotage into Brave ActionFrom EverandI Shouldn't Feel This Way: Name What’s Hard, Tame Your Guilt, and Transform Self-Sabotage into Brave ActionNo ratings yet

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!From EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)