Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ACT For Insomnia (ACT-I) by DR Guy Meadows - The Sleep School

Uploaded by

2qf4ffhsh2Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ACT For Insomnia (ACT-I) by DR Guy Meadows - The Sleep School

Uploaded by

2qf4ffhsh2Copyright:

Available Formats

ACT FOR INSOMNIA (ACT-I)

Dr Guy Meadows (PhD)

Abstract

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) offers a unique and gentle non-

drug based approach to overcoming chronic insomnia. It seeks to increase

people’s willingness to experience the conditioned physiological and

psychological discomfort commonly associated with not sleeping.

Such acceptance paradoxically acts to lessen the brains level of nocturnal

arousal, thus encouraging a state of rest and sleepiness, rather than struggle

and wakefulness. Additional focus on valued driven behaviour also acts to

avert unhelpful patterns of experiential avoidance and promote the ideal safe

environment from which good quality sleep can emerge.

The application and merits for using ACT approaches such as acceptance

and willingness, mindfulness and defusion and values and committed action

for the treatment of chronic insomnia are discussed and compared to the

traditional cognitive behavioural strategies.

Introduction

Sleep involves a slowing of psychological (e.g. decision making, problem

solving and emotional readiness) and physiological (e.g. heart rate, breathing

rate, blood pressure, bowel movements and muscle tone) processes at the

end of the day. It is a natural act that can’t be controlled and is characterized

by an acceptance of the natural rise in sleep drive associated with nighttime

and a willingness to let go of wakefulness.

By contrast, chronic insomnia is a difficulty sleeping that is characterized by a

state of hyper arousal, which interferes with the natural ability to initiate or

maintain sleep or achieve restorative sleep. Where insomnia is the primary

disorder, the initial trigger is often resolved. But sleeplessness is maintained

by a vicious cycle whereby poor sleep initiates worry about not sleeping,

which in turn elevates arousal levels leading to further poor sleep. The

© The Sleep School 2013 1

adoption of unhelpful coping strategies and the movement away from valued

living act to create an inflexible relationship with sleep.

Cognitive behaviour therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is the most widely used

treatment method. Its primary focus is based around symptom reduction via

changing the cognitive and behavioral conditions that perpetuate the

insomnia. It most commonly achieves this through a series of 1-hour

interventions delivered over a 6 – 8 week period.

Whilst these interventions have been proven to be effective at reducing

insomnia rates, some patients still struggle. Complaints typically focus around

the non-workable nature of the process used and the continued need for

patients to diarize their sleep and thoughts throughout the intervention.

Dalrymple et al. (2010) investigated how incorporating principles from

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999) into the

treatment of insomnia could potentially enhance the adherence to and

acceptability of such traditional CBT-I approaches. This opens up the debate

as to whether ACT approaches alone could be an effective insomnia

treatment.

The rationale for using ACT approaches within the treatment of insomnia and

the practical ways in which it could be implemented into therapy sessions are

discussed in this poster.

Acceptance

The vicious cycle of insomnia demonstrates that it is the unwillingness of

patients to experience the unwanted thoughts, emotions and physical

sensations associated with not sleeping and the ensuing struggle with them

that heightens arousal levels and perpetuates sleeplessness. Most

insomniacs can provide a long list of control-based strategies, including

traditional CBT-I techniques, they have implemented and yet which have

failed to improve their sleep. This focus on symptom reduction, which if

ineffective simply perpetuates the vicious cycle.

© The Sleep School 2013 2

It could be more effective to teach patients to adopt a more accepting attitude

towards what spontaneously arises when experiencing difficulty sleeping. The

greater willingness to experience poor sleep results in fewer struggles, less

arousal and paradoxically greater levels of sleepiness.

Practically, any initial insomnia assessment should include a detailed review

of the failed techniques previously used to improve sleep. Lundh (2005)

suggests that such an awareness of the futility of control-based strategies

could then be used as a starting point from which to guide a patient towards

alternative acceptance based approaches.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the ability to objectively and non judgmentally take notice of

your internal and external experiences as they unfold. It can help insomniacs

to stand back and observe their level of wakefulness or unwanted thoughts

and emotional reactions without becoming overly entangled or judging them, a

quality that is inherent in the normal act of falling to sleep.

Shifting patients towards an attitude of acceptance rather than the CBT-I

focus on symptom reduction seen with many of the traditional relaxation

strategies could be a way of short-circuiting the vicious cycle of insomnia.

Practically, insomniacs can be taught to mindfully notice their senses and the

movement of their breath, which they can then practice during the day. At

night such exercises can be used to help patients to notice and let go of their

struggles and return back to the present moment (e.g. noticing the touch of

the duvet on their toes or the gentle movement of their breathe). Care must be

taken to highlight the potential risk and futility of using mindfulness as a tool to

control the level of relaxation or sleep and to confirm the benefits of objective

noticing (e.g. the use of the quicksand metaphor can be helpful at this point).

Defusion

Defusion describes the ability to see thoughts and emotions for what they are

(e.g. naturally occurring cognitive and emotional responses) and create space

© The Sleep School 2013 3

for them to exist, rather than fusing with them or seeing them as something

that needs to be removed, before sleep can be restored.

Such acceptance once again bypasses the need to struggle with such internal

content by changing the patient’s relationship with the content. It could be

argued that such an energy efficient and low arousal approach is more

nocturnally intuitive than the traditional CBT-I based cognitive restructuring,

which requires patients to challenge their thoughts and then create new

alternative and balanced ones in their place.

Practically, patients spend time identifying their unwanted thoughts, emotions,

physical sensations and urges that show up when they don’t sleep. They are

then taught basic defusion exercises such as objectively describing, naming

and welcoming unhelpful thoughts when they arrive in the night such as “I am

having the thought that…” or “Hello, ‘coping’, ‘medication’ and ‘ill health’

thoughts”. For emotions and physical sensations, patients can practice

‘Physicalizing’ exercises such as objectively locating and describing them and

imagining them as objects and giving them a physical shape and colour.

Valued Sleep Actions

A normal sleeper has a strong relationship with their bed and bedroom,

meaning they can fall to sleep or return back to sleep very quickly and with

little effort. In contrast, an insomniac has a negative sleep association

meaning they become cognitively and emotionally alert at the point of trying to

sleep (e.g. conditioned bedtime arousal). The adoption of unhelpful coping

strategies in order to control sleep (e.g. going to bed early, sleeping in the

spare room or sleeping during the day), not only perpetuates poor sleep, but

also results in a reduction in valued living (e.g. not being able to go out at

night, share a bed with a partner or schedule early appointments), something

that patients cite as one of the main reasons for struggling with sleep in the

first place.

CBT-I approaches the problem by asking patients to follow a series of strict

rules known as Stimulus Control Therapy (SCT), see table 1. The aim is to

limit the time patients spend in the negative state or engaging in non-sleep

© The Sleep School 2013 4

activities, in the hope of developing a positive association, whereby sleep

onset occurs rapidly on getting into bed. Whilst SCT is widely used, many

patients complain that its strict nature is counter intuitive and goes against

normal valued sleep actions, see table 1. The result is that anxiety and

arousal levels associated with the bedroom and sleep are unhelpfully

heightened.

In contrast, teaching patients to commit to making behavioural changes in line

with their sleep and life values, whilst being willing to experience the

unwanted elements of the negative association could be an effective way of

re-establishing a positive association between sleep and bed. The aim is that

by promoting a healthy and flexible approach to sleep, any negative

associations and therefore arousal levels would be reduced, creating a

platform from which natural sleep could emerge effortlessly.

Table 1.

Valued Sleep Action CBT-I ACT-I

Allow normal NO YES

bedroom activities Use the bed for sleep and Allow calm non sleep

sex only activities such as reading

in bed

Go to bed when No Yes

either tired or sleepy Only when sleepy Both states allowed

Stay in bed, if awake NO YES

at night If not asleep within Focus on resting and

15mins, go to a spare welcoming discomfort

room and read

Allow daytime naps No Yes

Avoid all daytime napping Allow a short (<20mins)

daytime naps

Restricting Sleep

© The Sleep School 2013 5

Sleep is regulated by an internal body clock and a sleep homeostat, to keep it

on time and create its cyclical drive. A normal sleeper keeps a fairly regular

pattern by going to bed and getting up at roughly the same time four days per

week and a little later on the weekend. A common coping strategy of many

insomniacs is to change their sleep wake cycle in the hope of getting a little

more sleep (e.g. going to bed earlier, lying in later or catching up during the

day). Whilst such action may make cognitive sense, they do in fact worsen

nocturnal sleep by lowering the sleep efficiency (SE), the percentage of time

spent in bed asleep.

CBT-I approaches this problem using Sleep Restriction Therapy (SRT), which

restricts the time in bed to actual sleeping time only so as sleep drive

increases, so will sleep consolidation, which can then be steadily titrated back

to a normal level. Whilst such an approach can be affective, some patients

struggle with the concept of spending less time in bed. Many insomniacs also

present with sleep anxiety and so any suggestion of restricting the amount of

time in bed is often met with increased levels of anxiety and alertness, thus

counteracting any of the positive benefits of an increase in sleep drive,

possibly explaining the low adherence rates.

Practically, it is therefore advised that patient anxiety levels be considered

before the implementation of sleep restriction. If anxiety levels are found to be

high, then treatment should be focused on increasing patient willingness to

experience the anxiety, before then considering sleep restriction at a later

date (e.g. assuming reduced anxiety levels did not lead to improved sleep).

Conclusions

This poster puts forward the rationale for using Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy for Insomnia (ACT-I) and its potential benefits over traditional

cognitive behavioural treatments. It suggests that acceptance and

mindfulness based approaches are intuitively, psychologically and

physiologically more in tune with the natural process of deactivation

associated with falling to sleep. It places importance on the act of adopting

valued sleep actions, whilst being willing to experience the heightened

cognitive and emotional processes that present in response to not sleeping.

© The Sleep School 2013 6

Ultimately it seeks to promote a high level of sleep flexibility, thus leading to

less struggle and arousal, improved sleep quality and energy conservation

and enhanced quality of life.

References

Dalrymple, K.L., Fiorentino, L., Politi, M.C., & Posner, D., (2010). Incorporating Principles

from Aceptance and Commitment Therapy for Insomnia: A Case Example. J Contemp

Psychother, 40: 209-217.

Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., & Wilson, K.G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment t: An

experiential approach to behaviour change. New York: Guilford Press.

Lundh, L.G., (2005). The Role of Acceptance and Mindfulness in the Treatment of Insomnia.

J of Cog Psychother, 19: 29-39.

Additional Information

Dr Guy Meadows (PhD) is a sleep physiologist who runs The Sleep School a

private sleep clinic in London focusing on the use of Acceptance and

Commitment Therapy in the treatment of Insomnia. For further information

please visit: www.thesleepschool.org or email: guy@thesleepschool.org.

Alternatively please follow FB: The Sleep School or Twitter: DrGuyMeadows

© The Sleep School 2013 7

You might also like

- ACT For Sleep Protocol-FinalDocument17 pagesACT For Sleep Protocol-Finalkenny.illanesNo ratings yet

- Bellak Tat Sheet2pdfDocument17 pagesBellak Tat Sheet2pdfTalala Usman100% (3)

- Sleep Pattern DisturbanceDocument4 pagesSleep Pattern DisturbanceVirusNo ratings yet

- Risk assessment of crane workshopDocument13 pagesRisk assessment of crane workshopNauman Qureshi89% (9)

- Act For Insomnia Act I by DR Guy Meadows The Sleep SchoolDocument7 pagesAct For Insomnia Act I by DR Guy Meadows The Sleep SchoolDharmendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Insomnia: Nancy Nadolski, FNP, MSN, Med, RNDocument7 pagesTreatment of Insomnia: Nancy Nadolski, FNP, MSN, Med, RNTita Swastiana AdiNo ratings yet

- Overcoming-Insomnia Through YogaDocument9 pagesOvercoming-Insomnia Through YogarexyNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Is the Gold-Standard for Treating Chronic InsomniaDocument6 pagesCognitive Behavioral Therapy Is the Gold-Standard for Treating Chronic InsomniaMonica BurcaNo ratings yet

- MENTAL WELLBEING AND POSITIVE PSYCHIATRY TAKEAWAYSDocument5 pagesMENTAL WELLBEING AND POSITIVE PSYCHIATRY TAKEAWAYSBim arraNo ratings yet

- MBCT and MBSRDocument10 pagesMBCT and MBSRgargchiya97No ratings yet

- Insomnia: Management of Underlying ProblemsDocument6 pagesInsomnia: Management of Underlying Problems7OrangesNo ratings yet

- Aaft 14 I 1 P 33Document3 pagesAaft 14 I 1 P 33Zihan viranandaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Insomnia & Sleep: The Puppeteer Behind Sleep - Unraveling the Secrets of Circadian Rhythms and the Mastermind Controlling Your Sleep Patterns and Break Free from Insomnia's ClutchesFrom EverandCognitive Behavioral Therapy For Insomnia & Sleep: The Puppeteer Behind Sleep - Unraveling the Secrets of Circadian Rhythms and the Mastermind Controlling Your Sleep Patterns and Break Free from Insomnia's ClutchesNo ratings yet

- Stepanski2003 Use of Sleep Hygiene in The Treatment of InsomniaDocument11 pagesStepanski2003 Use of Sleep Hygiene in The Treatment of InsomniaM SNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Therapy Improves Sleep DisordersDocument12 pagesCognitive Therapy Improves Sleep DisordersJulian PintosNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Insomnia - Harvard Health PublicationsDocument5 pagesOvercoming Insomnia - Harvard Health PublicationssightbdNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness Meditation and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For TinnitusDocument3 pagesMindfulness Meditation and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Tinnitusavalon_moonNo ratings yet

- Sleep Well: A Guide on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for InsomniaFrom EverandSleep Well: A Guide on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for InsomniaNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pathways For General PractitionersDocument5 pagesAcceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pathways For General PractitionersAnonymous Ax12P2srNo ratings yet

- Classification 2018-2020, 11 Edition. "Insomnia" Is An Approved Nursing Diagnosis Under Domain 4, Class 1, Diagnosis Code 00095Document4 pagesClassification 2018-2020, 11 Edition. "Insomnia" Is An Approved Nursing Diagnosis Under Domain 4, Class 1, Diagnosis Code 00095Nicole Chloe OcanaNo ratings yet

- Management of Sleep Disorders in ElderlyDocument20 pagesManagement of Sleep Disorders in ElderlyRiyaSinghNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan Format Name: - Medical Diagnosis: - DateDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan Format Name: - Medical Diagnosis: - DateSheryl Ann Barit PedinesNo ratings yet

- Behavior TherapyDocument52 pagesBehavior TherapySajal SahooNo ratings yet

- Alternative-Complementary-Therapy-in-Labour SUBMISSIONDocument18 pagesAlternative-Complementary-Therapy-in-Labour SUBMISSIONSavita HanamsagarNo ratings yet

- MBCT Reduces Depression and Substance Abuse in Case StudyDocument24 pagesMBCT Reduces Depression and Substance Abuse in Case StudyAnet Augustine AnetNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Concepts of CounsellingDocument24 pagesCognitive Concepts of CounsellingArshiya SharmaNo ratings yet

- 9 Essential CBT Techniques and Tools PsychotherapyDocument4 pages9 Essential CBT Techniques and Tools Psychotherapyآئمہ توصيف100% (1)

- Techniques PrintedDocument14 pagesTechniques PrintedAzizNo ratings yet

- Ayt IiDocument2 pagesAyt IiAchieVia AchieViaNo ratings yet

- 978-3-031-10698-9 - 6 الفصل السادسDocument20 pages978-3-031-10698-9 - 6 الفصل السادسDoaa EissaNo ratings yet

- Primary Symptoms of Night Eating Syndrome AreDocument3 pagesPrimary Symptoms of Night Eating Syndrome AreAisa Shane100% (1)

- Review of Safety and Ef Ficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older AdultsDocument33 pagesReview of Safety and Ef Ficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older AdultsAlberto JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Jde Ding RCB T ManualDocument18 pagesJde Ding RCB T ManualLinNo ratings yet

- What Is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)Document11 pagesWhat Is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)Sharon ChinNo ratings yet

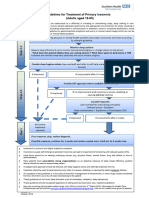

- NHS Guideline For Treatment of Primary Insomnia 2019Document2 pagesNHS Guideline For Treatment of Primary Insomnia 2019Oscar ChauNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Activation Group Therapy: Therapist ManualDocument37 pagesBehavioral Activation Group Therapy: Therapist ManualcaballeroNo ratings yet

- Sleep DeprivationDocument2 pagesSleep Deprivationhaha jahaNo ratings yet

- NCP 1 Nursing DiagnosisDocument6 pagesNCP 1 Nursing DiagnosisJosh BlasNo ratings yet

- Presentation of Psychotherapy Based On Paul Diel's Theory (Psychology of Motivation)Document5 pagesPresentation of Psychotherapy Based On Paul Diel's Theory (Psychology of Motivation)الاسراء و المعراجNo ratings yet

- Behavior Modification& Relaxation TrainingDocument33 pagesBehavior Modification& Relaxation TrainingHaleema SaadiaNo ratings yet

- The Sleep School - 1.5hr Plan For Duc Nguyen by Dr. Guy Meadows (PHD)Document26 pagesThe Sleep School - 1.5hr Plan For Duc Nguyen by Dr. Guy Meadows (PHD)DucNguyen100% (2)

- Adjustment DisorderDocument37 pagesAdjustment DisorderprabhaNo ratings yet

- CBT InsomniaDocument14 pagesCBT Insomniasharma.surabhi016No ratings yet

- Unit 3 Contingency ManagementDocument14 pagesUnit 3 Contingency ManagementaminaazhaNo ratings yet

- Behaviour TherPYDocument11 pagesBehaviour TherPYrupali kharabeNo ratings yet

- S.O.B.E.R. Stress Interruption 1Document5 pagesS.O.B.E.R. Stress Interruption 1Marjolein SmitNo ratings yet

- Biofeedback: Biofeedback-Assisted Relaxation TrainingDocument23 pagesBiofeedback: Biofeedback-Assisted Relaxation TrainingMythily VedhagiriNo ratings yet

- Et - Week 4 - Reflection in Critical Thinking Process - 2023 - S2 - StudentsDocument4 pagesEt - Week 4 - Reflection in Critical Thinking Process - 2023 - S2 - StudentstansihuishNo ratings yet

- Overview of The Treatment of Insomnia in Adults - UpToDateDocument24 pagesOverview of The Treatment of Insomnia in Adults - UpToDatePriscillaNo ratings yet

- 9 Essential CBT Techniques for Managing Mental HealthDocument3 pages9 Essential CBT Techniques for Managing Mental Healthsyarifah wardah el hilwaNo ratings yet

- OHC Brochure 2022Document36 pagesOHC Brochure 2022sara baileyNo ratings yet

- Problem PrioritizationDocument3 pagesProblem PrioritizationJohn Cenas0% (1)

- HYPNOSIS RAPID WEIGHT LOSS: Utilizing the Power of Hypnotherapy to Achieve Rapid and Sustained Weight Loss (2023)From EverandHYPNOSIS RAPID WEIGHT LOSS: Utilizing the Power of Hypnotherapy to Achieve Rapid and Sustained Weight Loss (2023)No ratings yet

- hw499 Unit 5 Cam Lesson 3 VanessaDocument2 pageshw499 Unit 5 Cam Lesson 3 Vanessaapi-254941267No ratings yet

- Waking Up To The Problem of Sleep: Can Mindfulness Help? A Review of Theory and Evidence For The Effects of Mindfulness For SleepDocument5 pagesWaking Up To The Problem of Sleep: Can Mindfulness Help? A Review of Theory and Evidence For The Effects of Mindfulness For SleepJulian PintosNo ratings yet

- CAM FinalecDocument62 pagesCAM FinalecmaridelleNo ratings yet

- Alternative & Complementary Therapy in LabourDocument14 pagesAlternative & Complementary Therapy in Labourhiral mistry86% (14)

- AP14 - DTC Support Manual - 20160930Document817 pagesAP14 - DTC Support Manual - 20160930tallerr.360No ratings yet

- Influence of Drug AbuseDocument45 pagesInfluence of Drug AbuseNigel HopeNo ratings yet

- Writ CallDocument4 pagesWrit CallSandhya GurunathNo ratings yet

- Kebutuhan Cairan NeonatusDocument3 pagesKebutuhan Cairan NeonatusGendis SudjaNo ratings yet

- TF-CBT and Complex TraumaDocument14 pagesTF-CBT and Complex TraumaDaniel Hidalgo LimaNo ratings yet

- Physical Education: Quarter 1 - Module 2: Physical Fitness ActivitiesDocument27 pagesPhysical Education: Quarter 1 - Module 2: Physical Fitness ActivitiesKeith Tristan RodrigoNo ratings yet

- Lgu CaDocument70 pagesLgu CaMENRO GENERAL NATIVIDADNo ratings yet

- Washington HospitalsDocument9 pagesWashington HospitalsJoe FrascaNo ratings yet

- Mobile Operating Tables For All Surgical ApplicationsDocument13 pagesMobile Operating Tables For All Surgical Applicationsibrahim hashimNo ratings yet

- NCM108 Module 1 EDocument12 pagesNCM108 Module 1 ESheera MangcoNo ratings yet

- Australian/New Zealand StandardDocument53 pagesAustralian/New Zealand Standardhitman1363100% (1)

- Tomczyk Dominika Resume 0812-2020Document1 pageTomczyk Dominika Resume 0812-2020api-535602662No ratings yet

- Overcome Anxiety, Depression and Gain ControlDocument3 pagesOvercome Anxiety, Depression and Gain ControlPranavNo ratings yet

- Client Package Manual (Evic Human Resource MGT., Inc.) - 1Document6 pagesClient Package Manual (Evic Human Resource MGT., Inc.) - 1Shalinur GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Engineering Technology - Mechanical Engineering Lab Report on Heat Transfer Safety Procedures RY57Document9 pagesFaculty of Engineering Technology - Mechanical Engineering Lab Report on Heat Transfer Safety Procedures RY57Muhammad SyuhailNo ratings yet

- New York Sars-Cov-2 Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase (RT) - PCR Diagnostic PanelDocument27 pagesNew York Sars-Cov-2 Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase (RT) - PCR Diagnostic PanelcassNo ratings yet

- DCP East District of Delhi - Complaint Under 144 - Code of Criminal ProcedureDocument113 pagesDCP East District of Delhi - Complaint Under 144 - Code of Criminal ProcedureNaresh KadyanNo ratings yet

- HardboundDocument88 pagesHardboundTyronne FelicitasNo ratings yet

- Bhat 2013Document5 pagesBhat 2013Irvin MarcelNo ratings yet

- Clostridioides Difficile Infection in Patients WitDocument10 pagesClostridioides Difficile Infection in Patients WitElena Cuiban100% (1)

- Safety ManualDocument21 pagesSafety ManualAli ImamNo ratings yet

- Catarina Miotto TortozaDocument2 pagesCatarina Miotto TortozacatNo ratings yet

- MEDUMAT Transport 83428-ENDocument16 pagesMEDUMAT Transport 83428-ENShota MukhashavriaNo ratings yet

- Checking Vital SignDocument11 pagesChecking Vital SignslemetiskandarNo ratings yet

- Health Guard Brochure Print76Document22 pagesHealth Guard Brochure Print76fhnNo ratings yet

- The Bennett Angle: Clinical Comparison of Different Recording MethodsDocument6 pagesThe Bennett Angle: Clinical Comparison of Different Recording MethodsFrank Bermeo100% (1)

- PED011 Final Req 15Document3 pagesPED011 Final Req 15macabalang.yd501No ratings yet

- MARGARITA BrandDocument32 pagesMARGARITA BrandCARDIAC8No ratings yet